Abstract

Background

Workers may be exposed to various types of occupational hazards at the same time, potentially increasing the risk of adverse health outcomes. The aim of this review was to analyze the effects of multiple occupational exposures and coexposures to chemical, biomechanical, and physical hazards on adverse health outcomes among agricultural workers.

Methods

Articles published in English between 1990 and 2015 were identified using five popular databases and two complementary sources. The quality of the included publications was assessed using the methodology developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project assessment tool for quantitative studies.

Results

Fifteen articles were included in the review. Multiple chemical exposures were significantly associated with an increased risk of respiratory diseases, cancer, and DNA and cytogenetic damage. Multiple physical exposures seemed to increase the risk of hearing loss, whereas coexposures to physical and biomechanical hazards were associated with an increased risk of musculoskeletal disorders among agricultural workers.

Conclusion

Few studies have explored the impact of multiple occupational exposures on the health of agricultural workers. A very limited number of studies have investigated the effect of coexposures among biomechanical, physical, and chemical hazards on occupational health, which indicates a need for further research in this area.

Keywords: Agricultural workers, Coexposures, Multiple exposures, Occupational hazards

1. Introduction

Nowadays, more than 30% of the world's population relies on agriculture for its livelihood [1]. Many agricultural countries, especially in Southeast Asia, are experiencing rapid intensification of agricultural and livestock production, which could critically affect ecosystems and human health [1], [2]. In the context of occupational safety and health, the term “agriculture” refers to a broad range of activities, including cultivation, growth, harvest, and primary processes relating to agricultural and animal products as well as livestock breeding, including both aquaculture and agroforestry [3].

Agriculture is one of the occupations most exposed to various hazards. It is also associated with the highest rate of adverse health outcomes each year worldwide [1]. Agricultural workers have been shown to be exposed to a variety of chemical hazards, such as pesticides and other chemical substances [4], [5]. Farm work may also expose workers to strenuous physical exercise and an extreme environment (i.e., low temperatures) [6], [7]. Furthermore, during their daily activities, agricultural workers operate various types of vehicles, machinery, and equipment [4], which can result in excessive exposures to noise and vibration [4], [8]. It has been suggested that these occupational exposures increase the risk of musculoskeletal disorders due to the harmful effects of biomechanical and physical factors [7], [9] or cancer, Parkinson's disease, and respiratory diseases due to pesticides [10], [11], [12], which may also cause other occupational diseases [13].

The relationship between a single occupational exposure and several adverse health outcomes has been well documented [14], [15]. Yet, an agricultural worker is very likely to be exposed simultaneously or sequentially to multiple occupational hazards, by various routes of exposure, from a variety of sources and over varying periods of time [16], [17]. Similarly, occupational disease or health impairment may often be due to exposure to multiple risk factors [18], [19]. Therefore, there is a need in documenting real working life situations of multiple and coexposures in line with the rising attention given to “exposome” and its potential relevance for reflecting workplace exposures [20]. This concept also raises other concerns, including potential for confounding and identifying synergistic or additive associations between multiple exposures and occupational health. Although some approaches for assessing combined exposure to multiple chemicals have been developed, there is still a challenge in incorporating nonchemical stressors into toxicity studies and cumulative risk assessments [20]. This is, of course, of particular importance not only in terms of hazard identification and risk assessment but also when it comes to target interventions to prevent occupational diseases in the agricultural sector [21].

However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no prior systematic review of multiple occupational exposures or coexposures in the agricultural sector. Moreover, based on the report of the International Labor Office at a national level, the cumulated incident rate of occupational diseases in the agricultural sector due to chemical, biochemical, and physical hazards was estimated to be 87.6 per 100,000 workers (vs. 3.6 per 100,000 workers for biological factors) [13]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to review previously published studies that examined associations between multiple occupational exposures and coexposures to chemical, biomechanical, and physical hazards on the one hand and adverse health outcomes on the other hand, among agricultural workers.

2. Materials and methods

The three types of occupational hazards explored in this study have been previously defined by CISME (Centre Interservices Santé et Médecine Travail Entreprise) [22]. Chemical hazards include harmful chemical compounds in the form of liquids, gasses, dust, fumes, and vapors that have been shown to exert toxic effects through direct application, product manufacture, or the industrial process. Physical hazards are environmental hazards (e.g., noise, vibration, temperature, radiation, etc.) that can damage human health with or without contact. Biomechanical hazards refer to manual tasks and postures (e.g., repetitive movements, static postures, forceful exertions, etc.) that have been shown to increase the risk of injuries or discomforts. In this review, we used the term “multiple exposures” to define exposure to more than one occupational hazard from the same hazard type group (i.e., exposures among two or more chemical agents; or among two or more physical factors; or among two or more biomechanical factors). Conversely, we used the term “coexposures” to define exposure to more than one occupational hazard from different hazard type groups (i.e., between biomechanical and chemical hazards; between biomechanical and physical hazards; between physical and chemical hazards; or between chemical, biomechanical, and physical hazards).

Studies were included based on three methodological steps. First, a systematic search based on selected keywords was applied to five databases and two complementary sources. Subsequently, a screening process was carried out on the retained articles. The references from the selected articles were also hand-searched for additional relevant studies. The final step involved full-text screening, which allowed us to verify the quality of the selected articles using the methodology developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) [23].

2.1. Phase 1: Systematic search strategy

2.1.1. Data sources

A peer literature review of studies published in English from January 1990 to August 2015 was performed using the databases ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Wiley-Blackwell. Additional publications from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH, USA) or based on the Agricultural Health Study (AHS) were also included. The AHS is a prospective cohort of licensed pesticide applicators and their spouses from Iowa and North Carolina (inclusion 1993–1997). The following English terms for agricultural occupations were used in our selection: farm, farmer(s), farming, farm worker(s), grower, planter, cultivator, stockman, peasant, feeder, harvester, breeder, tiller, granger, agriculture, agricultural worker(s), forestry worker(s), fishing, fishery, fisheries, fishery worker(s), aquaculture. The terms used to identify “exposure” were exposure(s) OR risk(s) OR hazard(s) OR co-exposure(s) OR coexposure(s). Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were applied to combine the “agricultural” and “exposure” terms according to the structure for the search of each database, specifically in Title/Abstract (PubMed), title only (ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, Web of Science, NIOSH, and AHS) and abstract only (Wiley-Blackwell).

2.1.2. Eligibility criteria

The reviewed publications had to comply with three criteria: It should (i) be an observational study, (ii) have statistical associations performed between multiple exposures/coexposures and adverse health outcomes, (iii) be published in English between 1990 and 2015.

Articles were excluded if (i) the definition/classification for occupational exposures were ambiguous; (ii) the health outcomes studied were injuries/accidents; and (iii) they involved limited study populations, such as pregnant agricultural workers.

2.2. Phase 2: Screening process

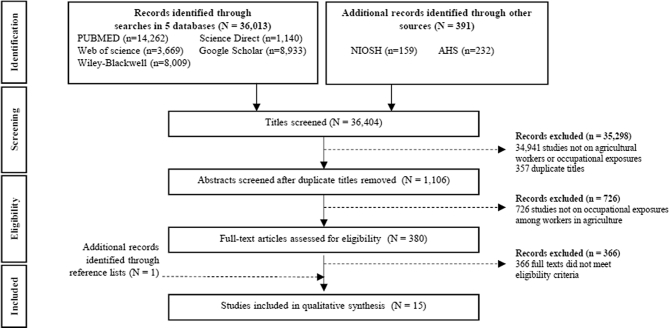

The screening process began with a selection based on titles. Publications were retained if they referred to agricultural workers or studied occupational exposures using the selected terms. After removing duplicates, potential articles were evaluated based on their abstracts. Studies were excluded if they did not mention occupational exposures among adult workers in agriculture. Additional articles were included by hand-searching the reference lists of the selected studies. Finally, full-text screening was carried out based on the items eligible, as detailed previously (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart for identifying studies for systematic literature search. AHS, Agricultural Health Study; NIOSH, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

2.3. Phase 3: Data collection and assessment of the quality of studies

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement for literature search and data collection [23]. The following data were then collected and synthetized for each study: first author, year of publication, study location, study population, study design, data collection, statistical analysis, confounding factors, and health outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description and characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review (N = 15).

| Hazards | Population | Study design | Statistical method | Confounders | Health outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple chemical exposures | ||||||

| Herbicides (acetochlor + atrazine) | Acetochlor applicators USA n = 4,026 (M) |

PC TI |

Poisson regression RR (95% CI) |

Age, race, state, applicator type, smoking status, family history of cancer, alcohol consumption, body mass index, use of an enclosed cab, and education correlated/associated pesticide use | Colorectal cancer: 1.03 (0.66–1.61) Lung cancer: 2.01 (1.17–3.46) Applied separately: 1.29 (0.45–3.68) Applied as a combination: 2.33 (1.30–4.17) Melanoma: 1.75 (0.97–3.14) Pancreatic cancer: 1.84 (0.67–5.08) |

Lerro et al (2015) [27] |

| Insecticides (organophosphate mixtures) | Paddy farmer Malaysia Cases: n = 160 (M) Controls: n = 160 (M) |

CS I & Cl |

Independent t test p < 0.05 |

Age, sex, and tobacco use | DNA damage: Farmers versus controls (comet tail length): 24.35 μm versus 12.8 μm p = 0.001 |

How et al (2015) [33] |

| Insecticides (carbamate, organophosphate, pyrethroid, and organochlorine mixtures) | Farmers Pakistan Cases: n = 47 (M) Controls: n = 50 (M) |

CS Q & Cl |

Linear regression model Means ratio (95% CI) |

Age, sex, history of smoking, and socioeconomic status | DNA damage: 2.28 (2.07–2.50) | Bhalli et al (2009) [39] |

| Insecticides (carbamate, organophosphate, and pyrethroid mixtures) | Cotton pickers Pakistan Exposed: n = 69 (F) Unexposed: n = 69 (F) |

CS Q & Cl |

Negative binomial regression Means ratio (95% CI) | Age | Cytogenetic damage: binucleated cells/total micronuclei: Exposed 1–5 years: 2.627 (2.226–3.101)/2.620 (2.271–3.023) Exposed 6–10 years: 2.828 (2.383–3.355)/2.649 (2.279–3.078) Exposed 11–15 years: 3.110 (2.604–3.715)/2.897 (2.478–3.388) Exposed ≥ 15 years: 3.434 (2.853–4.134)/3.380 (2.879–3.969) |

Ali et al (2008) [40] |

| Insecticides (dicofol + tetradifon) | Farmers Italy Cases: n = 124 (M) Controls: n = 659 (M) |

CC Q & I |

Logistic model OR (95% CI) |

Age, family history of prostate cancer, and interview type | Prostate cancer: Exposed: 2.8 (1.5–5.0) Exposed no more than 15 years: 2.4 (1.2–5.3) Exposed more than 15 years: 3.0 (1.3–7.0) |

Settimi et al (2003) [38] |

| Insecticides (organophosphate, organochlorine, and carbamate mixtures) | Pesticide sprayer Greece Green house: n = 29 Outdoor fields: n = 27 Controls: n = 30 |

CS Cl |

Chi-square test p < 0.05 |

Age and sex | Chromosome aberrations: Sprayer in plastic greenhouse versus sprayer in outdoor fields (Chromosome aberrations levels in average): 3.37 versus 1.88 p < 0.01 |

Kourakis et al (1996) [41] |

| Fungicides and insecticides | Farm residents Canada n = 2,938 (M) |

PC MQ |

Logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

Age, marital status, comorbidity including diabetes and history of cardiovascular disease | Prostate cancer: 2.23 (1.15–4.33) | Sharma et al (2015) [28] |

|

Insecticide (chlorpyrifos) + other chemical agents (asbestos, engine exhaust, and silica/sand dust) |

Chlorpyrifos applicators USA n = 21,859 (M) n = 322 (F) |

PC Q |

Poisson regression RR (95% CI) |

Age, sex, alcohol consumption, history of smoking, education level, family history of cancer, year of enrollment, state of residence, and use of the four pesticides which is most highly correlated with use of chlorpyrifos | Lung cancer: Chlorpyrifos + engine exhaust: 2.10 (1.01–4.37) Chlorpyrifos + asbestos: 3.54 (1.47–8.51) Chlorpyrifos + silica/sand dust: 5.11 (1.98–13.22) |

Lee et al (2004) [37] |

|

Herbicides Bentazon + atrazine Bromoxynil + MCPA Butylate + crop protectant EPTC + crop protectant Fungicides Captan + lindane Carbathiin + thiram Carbathiin + thiram + lindane Insecticides Carbaryl + NAA Fumigant 1,2-Dichloropropane + 1,3-dichloropropene |

Farmers Canada Cases: n = 1,516 (M) Controls: n = 4,994 (M) |

CC Q |

Logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

Alcohol consumption, history of smoking status, education level, history of smoking a pipe, and respondent | Prostate cancer: Bentazon + atrazine: 1.51 (0.62–3.72) Bromoxynil + MCPA: 1.82 (0.93–3.57) Butylate + crop protectant: 1.70 (0.61–4.77) EPTC + crop protectant: 1.61 (0.79–3.27) Captan + lindane: 5.03 (1.65–15.35) Carbathiin + thiram: 1.90 (0.81–4.45) Carbathiin + thiram + lindane: 3.28 (0.90–11.99) Carbaryl + NAA: 1.44 (0.75–2.79) 1,2-Dichloropropane + 1,3-dichloropropene: 1.72 (0.76–3.92) |

Band et al (2011) [34] |

| Pesticides (multiple pesticides) | Farm women USA n = 25,814 (F) |

PC Q & TI |

Logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

Age, state, smoking status, body mass index, and “grew up on farm” | Asthma atopic ≥3 pesticides: 1.63 (1.09–2.45) |

Hoppin et al (2008) [30] |

| Pesticides (multiple pesticides) | Nonsmoking farm women USA n = 21,541 (F) |

PC Q |

Logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

Age and state | Chronic bronchitis ≥3 pesticides: 1.58 (1.19–2.09) |

Valcin et al (2007) [31] |

| Agricultural chemicals (Gasoline + solvent to clean) | Wheezing farmers USA n = 3,832 (M) n = 90 (F) |

PC Q |

Logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

Age, state, smoking status, asthma, atopy, asthma with atopy, and current smoking with asthma | Wheezing Low frequency use: 1.26 (1.16–1.36) Medium frequency use: 1.37 (1.19–1.57) High frequency use: 1.71 (1.33–2.20) |

Hoppin et al (2004) [36] |

| Multiple physical exposures | ||||||

| Noise + hand-arm vibration | Forestry workers Canada n = 8,526 (M) |

C MR |

Log-binomial regression PR |

Age-related hearing loss and exposure dose | Hearing loss Noise ≥ 90 dBA, hand-arm vibration, and duration of exposure ≥ 25 years: PR = 2.96 |

Turcot et al (2015) [29] |

| Coexposure | ||||||

| Combined biomechanical hazard (biomechanical load) + physical hazard (vibration) | Farmers The Netherlands Cases SL-BP: n = 733 SL-EXT: n = 276 Controls: n = 3,596 |

CC Q |

Logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

Age and smoking status | Sick leave due to back disorder (SL-BP) Medium exposure: 3.28 (2.04–9.13) High exposure: 4.32 (1.46–7.39) Sick leave due to neck, shoulder, or upper extremity disorders (SL-EXT) Medium exposure: 2.38 (0.93–6.13) High exposure: 3.30 (1.28–8.51) |

Hartman et al (2005) [35] |

| Biomechanical hazard (postural stress) + physical hazard (vibration) | Agricultural tractor drivers Italy Cases: n = 1155 (M) Controls: n = 220 (M) |

CC MQ & I |

Logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

Age, body mass index, education, sport activity, car driving, marital status, mental stress, climatic conditions, and back trauma | Low back pain: Vibration dose (5 level: 5; 10; 20; 30; 40 years m2/s4) with postural load (4 grades: 1–mild/2–moderate/3–hard/4–very hard) 5 years m2/s4 (vibration) in combination with 4 levels of postural load (mild; moderate; hard; very hard, respectively): 1.29; 1.79; 2.50; 3.48 10 years m2/s4 (vibration) in combination with 4 levels of postural load (mild, moderate, hard, very hard, respectively): 1.41; 1.96; 2.73; 3.79 20 years m2/s4 (vibration) in combination with 4 levels of postural load (mild, moderate, hard, very hard, respectively): 1.55; 2.15; 2.99; 4.16 30 years m2/s4 (vibration) in combination with 4 levels of postural load (mild, moderate, hard, very hard, respectively): 1.63; 2.27; 3.16; 4.39 40 years m2/s4 (vibration) in combination with 4 levels of postural load (mild, moderate, hard, very hard, respectively): 1.70; 2.36; 3.29; 4.58 |

Bovenzi & Betta (1994) [32] |

C, cohort study; CC, case–control study; Cl, clinical; CS, cross-sectional study; F, female; I, interview; M, male; MQ, mailed questionnaire; MR, medical record; PC, prospective cohort study; Q, questionnaire; TI, telephone interview.

OR: Odds ratio; PR: Prevalence ratio; RR: Relative risk; 95% CI: 95% Confidence interval.

Study quality was assessed using the protocol developed by the EPHPP for quantitative studies [24]. For observational studies, this quality criterion assessed the publications based on six items: (A) selection bias, (B) study design, (C) confounders, (D) blinding, (E) data collection methods, (F) withdrawals and dropouts. Each of these items was rated as strong, moderate, or weak according to the EPHPP protocol (Table 2). Finally, a study was globally classified as strong if no weak items were noted among the six, moderate if at least one criterion was classified as weak, and weak if two or more items were classified as weak [25], [26].

Table 2.

Items and rating of the quality assessment tool for quantitative studies according to the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP).

| Component | Rate this section |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Moderate | Weak | |

| A) Selection bias | |||

| Are the individuals selected to participate in the study likely to be representative of the target population? | Very likely to be representative of the target population; more than 80% participation | Somewhat likely to be representative of the target population; a 60–79% participation rate | Not likely to be representative of the target population; less than 60% participation rate |

| What percentage of selected individuals agreed to participate? | |||

| B) Study design | |||

| Indicate the study design: … | Randomized controlled trials or controlled clinical trials | Cohort analytical study, case–control study, cohort design, or interrupted time series | Other method or study design not stated |

| Was the study described as randomized? | |||

| Was the method of randomization described? | |||

| Was the method appropriate? | |||

| C) Confounders | |||

| Were there important differences between groups before the intervention? | Controlled for at least 80% of relevant confounders | Controlled for 60–79% of relevant confounders | Less than 60% of relevant confounders were controlled |

| Indicate the percentage of relevant confounders that were controlled: … | |||

| D) Blinding | |||

| Was (were) the outcome assessor(s) aware of the intervention or exposure status of participants? | Not aware of the intervention status of participants for the outcome assessor; not aware of the research question for the participants | Not aware of the intervention status of participants for the outcome assessor; not aware of the research question for the participants | Aware of the intervention status of participants for the outcome assessor; aware of the research question for the participants |

| Were the study participants aware of the research question? | |||

| E) Data collection methods | |||

| Are data collection tools shown to be valid? | Shown to be valid and reliable | Shown to be valid; not reliable or reliability not described | Not shown to be valid; both reliability and validity not described |

| Are data collection tools shown to be reliable? | |||

| F) Withdrawals and dropouts | |||

| Were withdrawals and dropouts reported in terms of numbers and/or reasons per group? Indicate the percentage of participants who completed the study: … |

80% or higher follow-up rate | 60–79% follow-up rate | Less than 60% follow-up rate or withdrawals and dropouts not described |

3. Results

3.1. Literature search

A total of 36,404 studies were initially considered based on our search of the five databases and two other complementary sources (NIOSH and AHS). After removing duplicate articles (n = 357) and articles not matching our inclusion criteria based on titles (n = 34,941) and abstract screening (n = 726), 380 full texts were submitted to the reviewing process. Ultimately, 15 articles (including 1 additional article from the relevant references) matching all the screening conditions were included in the systematic review (Fig. 1).

Table 3 shows the main characteristics of the articles selected. Most studies were carried out in the United States or Canada, mainly because of our inclusion process (publications based on AHS or coordinated by NIOSH). Studies exploring the combination of occupational exposures among agricultural workers were shown to increase over the years, with 66.7% of the selected articles published between 2000 and 2015. Among the 15 publications retained, four were cross-sectional studies, four were case–control studies, and seven were cohort studies. Interviews or questionnaires accounted for approximately two-thirds of the data collection techniques. Logistic regression models were mainly used in the reviewed articles (66.7%). Most studies assessed the impact of multiple chemical exposures on diverse health outcomes (80%). Coexposures and multiple physical exposures were investigated in 13.3% and 6.7% of the selected studies, respectively, whereas none explored the impact of multiple occupational biomechanical exposures on the health of agricultural workers. Cancer was the main health outcome examined among the selected studies, followed by DNA and cytogenetic damage (26.7%), respiratory diseases (20%), musculoskeletal disorders (13.3%), and hearing loss (6.7%).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studies included (n = 15).

| Characteristics of included studies | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Study location | ||

| Africa/America | 0 | 0.0 |

| Asia | 3 | 20.0 |

| Europe | 4 | 26.7 |

| United States/Canada | 8 | 53.3 |

| Study design | ||

| Case–control study | 4 | 26.7 |

| Cohort study | 7 | 46.7 |

| Cross-sectional study | 4 | 26.7 |

| Data collection | ||

| Interview/Questionnaire | 10 | 66.7 |

| Medical records/Clinical examination | 2 | 13.3 |

| Mixed ≥ 2 types | 3 | 20.0 |

| Occupational exposures explored | ||

| Multiple biomechanical exposures | 0 | 0.0 |

| Multiple chemical exposures | 12 | 80.0 |

| Multiple physical exposures | 1 | 6.7 |

| Coexposures | 2 | 13.3 |

| Year of publication | ||

| 1990–1994 | 1 | 6.7 |

| 1995–1999 | 1 | 6.7 |

| 2000–2004 | 3 | 20.0 |

| 2005–2009 | 5 | 33.3 |

| 2010–2015 | 5 | 33.3 |

| Statistical test/model | ||

| Chi-square | 1 | 6.6 |

| t test | 1 | 6.7 |

| Logistic regression | 10 | 66.7 |

| Poisson regression | 2 | 13.3 |

| Regression model | 1 | 6.7 |

| Health outcome | ||

| Cancer | 5 | 33.3 |

| DNA and cytogenetic damage | 4 | 26.7 |

| Respiratory diseases | 3 | 20.0 |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 2 | 13.3 |

| Hearing loss | 1 | 6.7 |

3.2. Methodological quality

Table 4 shows the results relating to the quality of the studies retained based on the six EPHPP items. Overall, six studies ([27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]) were classified as strong, and six ([33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]) were ranked as moderate. The remaining three articles ([39], [40], [41]) were considered as weak. None of the 15 studies were classified as strong based on their study design. However, from 20% to 26.7% of the selected studies were classified as strong based on their assessment of selection bias, blinding, data collection method, and withdrawal and dropout items. Confounding factors were almost always included in the selected studies (13 studies examined this quality item).

Table 4.

Results of quality assessment of the studies included following EPHPP six-item protocol.

| Author | Rating for each item |

Global rating for the article | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) Selection bias | B) Study design | C) Confounders | D) Blinding | E) Data collection methods | F) Withdrawals and dropouts | ||

| Lerro et al (2015) | M | M | S | M | M | M | S |

| How et al (2015) | S | W | S | S | S | M | M |

| Bhalli et al (2009) | M | W | S | S | S | W | W |

| Ali et al (2008) | W | W | W | M | M | S | W |

| Settimi et al (2003) | S | M | W | M | M | S | M |

| Kourakis et al (1996) | M | W | S | S | M | W | W |

| Sharma et al (2015) | M | M | S | M | M | M | S |

| Lee et al (2004) | W | M | S | M | M | M | M |

| Band et al (2011) | M | M | S | M | M | W | M |

| Hoppin et al (2008) | M | M | S | M | M | M | S |

| Valcin et al (2007) | M | M | S | M | M | M | S |

| Hoppin et al (2004) | W | M | S | M | M | M | M |

| Turcot et al (2015) | S | M | S | S | S | M | S |

| Hartman et al (2005) | M | M | S | M | M | W | M |

| Bovenzi & Betta (1994) | S | M | S | M | M | S | S |

| Strong n (%) | 4 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (86.7) | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20.0) | 3 (20.0) | 6 (40.0) |

| Moderate n (%) | 8 (53.3) | 11 (73.3) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (73.3) | 12 (80.0) | 8 (53.3) | 6 (40.0) |

| Weak n (%) | 3 (20.0) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20.0) |

EPHPP, Effective Public Health Practice Project; M, moderate; S, strong; W, weak.

3.3. Multiple occupational exposures and coexposures to chemical, biomechanical, and physical hazards

3.3.1. Multiple chemical exposures

Among the 12 studies exploring multiple chemical exposures (Table 4), five publications were based on the AHS [27], [30], [31], [36], [37]. Multiple occupational exposures to different types of chemicals were associated with an increased risk of adverse health effects, including cancer [27], [28], [34], [37], [38], diseases related to the respiratory system [30], [31], [36], and DNA and cytogenetic damage [33], [39], [40], [41].

Few studies have examined the combined effect of different types of pesticides on agricultural workers' health. Exposures to the combination of two pesticides (acetochlor and atrazine) have been significantly associated with an increased risk of lung cancer [odds ratio (OR) 2.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17–3.46] among male farmers; this risk been higher for farmers using the two pesticides simultaneously in a mixture (OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.30–4.17) than for those using successively across time (OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.45–3.68) [27]. The combination of dicofol and tetradifon insecticides has also been associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer, the risk linearly growing with exposure duration [38]. Sharma et al (2015) have suggested a significant association between occupational exposures to both insecticides and fungicides and prostate cancer (OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.15–4.33), whereas no significant association with prostate cancer was observed when farmers used either only insecticides (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.55–3.15) or fungicides (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.26–3.63) [28]. In another study, exposure to chlorpyrifos combined with engine exhaust, asbestos, or silica/sand dust was significantly associated with an increased risk of lung cancer (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.01–4.37; OR 3.54, 95% CI 1.47–8.51; and OR 5.11, 95% CI 1.98–13.22, respectively), whereas these associations were not significant for the farmers only exposed to engine exhaust, asbestos, or silica/sand dust (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.79–2.30; OR 1.42, 95% CI 0.86–2.36; and OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.84–2.24, respectively) [37]. Occupational exposure to a fungicide mixture of captan and lindane was also associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer among farmers (OR = 5.03, 95% CI 1.65–15.35) [34].

Three studies have also suggested an effect of multiple chemical exposures on respiratory diseases. Female farmers had a higher risk of atopic asthma if they used three or more pesticides in their lifetime (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.09–2.45), and the associated risk was lower if only one pesticide was used (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.04–1.85) [30]. Multiple chemical exposures (≥3 pesticides) have also been significantly associated with chronic bronchitis among nonsmoking females (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.19–2.09), converse to the use of only one pesticide (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.90–1.38) [31]. Farmers' exposures to both gasoline and cleaning solvents were associated with an increased risk of wheezing (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.33–2.20), and the risk increased with the frequency of use [36].

3.3.2. Multiple physical exposures

Multiple physical exposures such as noise and vibration have previously been associated with health impairment [29]. Forestry workers exposed to both noise ≥90 dBA and hand-arm vibration (vibration was assessed using vibration white finger as a proxy) for a minimum duration of 25 years have been associated with an increased risk of hearing loss (prevalence ratio 2.96, p < 0.001) [29].

3.3.3. Coexposures to two different types of hazards

Only two observational studies included in this review have assessed the effects of coexposures on adverse health outcomes among agricultural workers. Hartman et al (2005) have observed an increased risk of sick leave due to low back disorders associated with an exposure to combined physical loads (Ref: Low, Medium: OR 3.28, 95% CI 2.04–9.13, High: OR 4.32, 95% CI 1.46–7.39) among farmers. The associated risk was lower among farmers only exposed to one physical or biomechanical exposure [35]. A significant association have been observed between high combined exposures to physical loads and sick leave due to neck, shoulder, and upper extremities disorders (Ref: Low, Medium: OR 2.38, 95% CI 0.93–6.13, High: OR 3.30, 95% CI 1.28–8.51). However, similar associations have also been suggested for each physical load taken independently [35]. Bovenzi and Betta (1994) have explored the effect of occupational coexposures to both physical (i.e., vibration) and biomechanical (i.e., postural stress) factors among agricultural tractor drivers. A positive linear trend of chronic low back pain was noticed among workers exposed to 5 years m2/s4 vibrations and postural stress. An increased duration of exposure to vibrations was also shown to be linearly and positively associated with chronic low back pain [32].

4. Discussion

Each year, 170,000 agricultural workers die because of their occupational activity, and millions suffer from occupational health problems [42]. To date, many studies have explored the association between a single exposure and health outcomes, whereas very few have explored the combined effects of occupational exposures [43]. We accounted for 15 publications that investigated the effects of multiple occupational exposures and coexposures on adverse health effects among agricultural workers. More than a third of these were publications from NIOSH and/or based on the AHS, which explains the high rate of studies from the USA and Canada.

4.1. Methodological quality in observational studies

To assess the methodological quality of the selected studies [44], we used the protocol developed through the EPHPP project that has previously demonstrated properties, including reliability and viability, to assess systematic reviews [45]. To the best of our knowledge, no consensus for a valid quality assessment tool for observational studies has been adopted to date [46]. The use of the EPHPP protocol was therefore adapted in our review; however, some limitations are inherent at this scale. Indeed, the impact of the items could differ between studies. Owing to the frame of the observational studies, the study design and confounding items weighted more than blinding or withdrawal items. Marking equal weight to all the items resulted in a comprehensive assessment in this case. Moreover, only randomized controlled trial studies could be ranked as strong using the EPHPP protocol. In contrast, all the remaining types of observational studies could only be classified as moderate or weak. Consequently, there is a need for a scientific consensus on the key elements to assess susceptibility to bias and develop unified quality tools for observational epidemiology.

4.2. Multiple occupational exposures and coexposures to chemical, biomechanical, and physical hazards

Farmers' frequent use of chemical agents in performing their occupational activities means that they are at risk of potentially high exposure to such products. Consequently, several articles have assessed the influence of chemical compounds on occupational health in the agricultural sector. About 80% of the articles included in this systematic review explored the association of multiple chemical exposures, exclusively pesticides, with adverse health outcomes among agricultural workers. Most of these have shown a significant increased risk of adverse health outcomes, primarily various cancers (prostate and lung) [27], [28], [34], [37], [38], cytogenetic/DNA damage [33], [39], [40], [41], or respiratory disease [30], [31], [36] among farmers multiexposed as compared with farmers not exposed or farmers exposed to a single pesticide.

Multiple physical exposures (i.e., vibration and noise) have been associated with a threefold increased risk of hearing loss [29]. Although agricultural workers are very likely to be exposed to various biomechanical and physical activities, assessment of biomechanical and physical coexposures has rarely been investigated. Two studies have shown an increasing risk of musculoskeletal disorders (i.e., low back pain and upper extremity disorders) among agricultural workers coexposed to biomechanical and physical factors as compared with their counterparts exposed only to physical hazards [32], [35].

Furthermore, there is no study on physical and chemical coexposures or on biomechanical and chemical coexposures among agricultural workers, probably due to the multidisciplinary approach requirement to explore such coexposures (from the genesis of biological pathways hypothesis to the development of relevant studies).

4.3. Implications for future research and practice

According to the International Labor Office, agriculture is one of the most exposed business sectors [1]. Our findings suggest that epidemiological studies exploring multiple occupational exposures among agricultural workers are required, especially taking into account occupational exposures beyond chemical ones, such as physical and biomechanical exposures. These results also suggest a need to further assess potential confounding, synergism, or additive effects of multiple occupational exposures and coexposures on adverse health outcomes in designed experiments or observational occupational studies.

No studies included in this review explored either coexposures to both physical and chemical agents or coexposures to biomechanical and chemical agents. Yet, physical work causes increased heart rate, respiratory function, and sweating, which facilitates the inhalation or dermal absorption of chemicals [47]. Physical constraints (e.g., repetitive gestures and vibration) are well established as the potential hazards for carpal tunnel syndrome [48], which raises concerns about a potential synergy between a physical and a chemical factor, especially if the chemical is neurotoxic and has an effect on the peripheral nervous system. Further studies investigating the effects of such coexposures are therefore required to identify their prevalence and their potential impact on farmers' health. It would also be worthwhile to improve the effectiveness of prevention strategies and programs in occupational health and for work-related musculoskeletal disorders [49].

The studies analyzed did not allow us to highlight gender differences. On the one hand, physical and biomechanical co-exposures were explored only among male agricultural workers. On the other hand, multiple pesticide exposures were explored among both genders; however, the outcomes of interest differed: studies on females focused on the respiratory system (atopic asthma [30] and chronic bronchitis [31]), whereas studies on males were more likely to assess impact on the risk of cancer, musculoskeletal disorders, and hearing loss [29]. However, previous studies have observed gender differences in the respiratory health of workers exposed to organic and inorganic dusts, particularly work-related asthma [50], [51]. These differences strongly contributed to the fact that adverse health outcomes due to multiple occupational exposures may differ between genders [52]. Consequently, further studies are required to also assess the effect modification of gender on multiple occupational exposures impact on adverse health outcomes.

5. Conclusion

Agricultural workers face multiple exposures and coexposures at the workplace. To date, however, few studies have focused on this issue. Among the studies that have assessed the effect of multiple exposures on agricultural workers' health, they focused their investigation on multiple chemical exposures. Consequently, further research assessing occupational coexposures to chemical, biomechanical, and physical hazards and their impact on health is required to contribute to the development of effective occupational health prevention strategies.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The study was supported by the French National Research Program for Environmental and Occupational Health of Anses (Grant EST-2014/1/077).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sébastien FAURE, professor in oxidative stress and metabolic pathologies at the University of Angers, Jean-François GÉHANNO, MD and professor in the occupational health service and professional pathology at Rouen University Hospital, and Xavier PASCAL, statistician in the ESTER Team (Inserm UMR_S 1085, Irset), for their valuable support with research strategies and technical assistance.

References

- 1.ILO . International Labour Office; Geneva: 2011. Safety and Health in agriculture. ILO code of practice.http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–ed_dialogue/–sector/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_161135.pdf Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen-Viet H., Doria S., Tung D., Mallee H., Wilcox B.A., Grace D. Ecohealth research in Southeast Asia: past, present and the way forward. Infect Dis Poverty. 2015;4:5. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markus P., Bob A. Occupational health and safety in agriculture. Sustain Agric. 2012:391–499. [Google Scholar]

- 4.White G., Cessna A. Occupational hazards of farming. Can Fam Physician. 1989;35:2331–2336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edson E.F. Chemical hazards in agriculture. Ann Occup Hyg. 1969;12:99–108. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/12.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson L.L., Rosenberg H.R. Preventing heat-related illness among agricultural workers. J Agromed. 2010;15:200–215. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2010.487021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osborne A., Blake C., Fullen B.M., Meredith D., Phelan J., Mcnamara J., Cunningham C. Risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders among farm owners and farm workers: a systematic review. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55:376–389. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.EU-OSHA . European Agency for Safety and Health at Work; Luxembourg: 2011. Maintenance in agriculture – a safety and health guide.https://osha.europa.eu/en/tools-and-publications/publications/reports/maintenance-in-agriculture-a-safety-and-health-guide Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker-Bone K., Palmer K.T. Musculoskeletal disorders in farmers and farm workers. Occup Med Chic Ill. 2002;52:441–450. doi: 10.1093/occmed/52.8.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freire C., Koifman S. Pesticide exposure and Parkinson's disease: epidemiological evidence of association. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:947–971. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye M., Beach J., Martin J.W., Senthilselvan A. Occupational pesticide exposures and respiratory health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:6442–6471. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10126442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.INSERM . Inserm; Paris: 2013. Pesticides: effets sur la santé.http://www.ipubli.inserm.fr/handle/10608/4819 Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ILO . Safe work; Geneva: 2000. Safety and health in agriculture.http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–ed_protect/–protrav/–safework/documents/publication/wcms_110193.pdf Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Checkoway H., Pearce N., Kriebel D. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; USA: 2003. Research methods in occupational epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy B.S., Wegman D.H., Halperin W.E., Baron S.L., Sokas R.K. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2006. Recognizing occupational and environmental disease and injury. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safe Work Australia . Safe Work Australia; Canberra: 2015. Exposure to multiple hazards among Australian workers.https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/exposure-to-multiple-hazards-report.pdf Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO . World Health Organisation; Geneva: 1995. Global strategy on occupational health for all the way to health at work.http://www.who.int/occupational_health/en/oehstrategy.pdf?ua=1 Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walter S.D. Prevention for multifactorial diseases. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112:409–416. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman K.J. Causes. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:90–95. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wild C.P. The exposome: from concept to utility. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:24–32. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehtola M.M., Rautiainen R.H., Day L.M., Schonstein E., Suutarinen J., Salminen S., Verbeek J.H. Effectiveness of interventions in preventing injuries in agriculture – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2008;34:327–336. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CISME . 2017. Thesaurus harmonisé des expositions professionnelles.http://www.presanse.fr/wpFichiers/1/1/Ressources/File/THESAURUS/versions_pour_2017/THESAURUS%20EXPOSITIONS%20PROFESSIONNELLES%20VERSION%20BETA%202%20-%20QUALIFICATIFS%202017%20-%20VERSION%20DU%2027-02-2017.pdf Version Beta 2. Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.EPHPP . 2010. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies.http://www.ephpp.ca/PDF/Quality%20Assessment%20Tool_2010_2.pdf Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 25.EPHPP . 2009. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Dictionary.http://www.ephpp.ca/PDF/QADictionary_dec2009.pdf Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas B.H., Ciliska D., Dobbins M., Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerro C.C., Koutros S., Andreotti G., Hines C.J., Blair A., Lubin J., Max X., Zhang Y., Beane Freeman L.E. Use of acetochlor and cancer incidence in the Agricultural Health Study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1167–1175. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma M., Lawson J.A., Kanthan R., Karunanayake C., Hagel L., Rennie D., Dosman J.A., Pahwa P., Saskatchewan Rural Cohort Study Group Factors associated with the prevalence of prostate cancer in rural Saskatchewan: the Saskatchewan rural health study. J Rural Heal. 2015;0:1–11. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turcot A., Girard S.A., Courteau M., Baril J., Larocque R. Noise-induced hearing loss and combined noise and vibration exposure. Occup Med. 2015;65:238–244. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoppin J.A., Umbach D.M., London S.J., Henneberger P.K., Kullman G.J., Alavanja M.C.R., Sandler D.P. Pesticides and atopic and nonatopic asthma among farm women in the Agricultural Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:11–18. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-821OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valcin M., Henneberger P.K., Kullman G.J., Umbach D.M., London S.J., Alavanja M.C., Sandler D.P., Hopin J.A. Chronic bronchitis among non-smoking farm women in the Agricultural Health Study. J Occup Env Med. 2007;49:574–583. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3180577768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bovenzi M., Betta A. Low-back disorders in agricultural tractor drivers exposed to whole-body vibration and postural stress. Appl Ergon. 1994;25:231–241. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.How V., Hashim Z., Ismail P., Omar D., Md Said S., Tamrin S.B.M. Characterization of risk factors for DNA damage among paddy farm worker exposed to mixtures of organophosphates. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2015;70:102–190. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2013.823905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Band P.R., Abanto Z., Bert J., Lang B., Fang R., Gallagher R.P., Le N.D. Prostate cancer risk and exposure to pesticides in British Columbia farmers. Prostate. 2011;71:168–183. doi: 10.1002/pros.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartman E., Oude Vrielink H.H.E., Metz J.H.M., Huirne R.B.M. Exposure to physical risk factors in Dutch agriculture: effect on sick leave due to musculoskeletal disorders. Int J Ind Ergon. 2005;35:1031–1045. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoppin J.A., Umbach D.M., London S.J., Alavanja M.C.R., Sandler D.P. Diesel exhaust, solvents, and other occupational exposures as risk factors for wheeze among farmers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1308–1313. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1228OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee W.J., Hoppin J.A., Blair A., Lubin J.H., Dosemeci M., Sandler D.P., Alavanja M.C. Cancer incidence among pesticide applicators exposed to cholorpyrifos in the Agricultural Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:373–380. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Settimi L., Masina A., Andrion A., Axelson O. Prostate cancer and exposure to pesticides in agricultural settings. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:458–461. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhalli J.A., Ali T., Asi M.R., Khalid Z.M., Ceppi M., Khan Q.M. DNA damage in Pakistani agricultural workers exposed to mixture of pesticides. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2009;50:37–45. doi: 10.1002/em.20435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali T., Bhalli J.A., Rana S.M., Khan Q.M. Cytogenetic damage in female Pakistan agricultural workers exposed to pesticides. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2008;49:374–380. doi: 10.1002/em.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kourakis A., Mouratidou M., Barbouti A., Dimikiotou M. Cytogenetic effects of occupational exposure in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of pesticide sprayers. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:99–101. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.ILO . International Labour Office; Geneva: 2003. Safety in numbers.http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–ed_protect/–protrav/–safework/documents/publication/wcms_142840.pdf Available at: [Accessed 2 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith D.R. Establishing national priorities for Australian occupational health and safety research. J Occup Health. 2010;52:241–248. doi: 10.1539/joh.p10001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manchikanti L., Datta S., Smith H.S., Hirsch J.A. Evidence-based medicine, systematic reviews, and guidelines in interventional pain management: part 6. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Pain Physician. 2009;12:819–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armijo-Olivo S., Stiles C.R., Hagen N.A., Biondo P.D., Cummings G.G. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lang S., Kleijnen J. Quality assessment tools for observational studies: lack of consensus. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2010:247. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2010.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petit A., Dupas D., Harry P., Nicolas A., Roquelaure Y. Etude de la co-exposition aux contraintes physiques et aux produits chimiques neurotoxiques chez les salaries des Pays de la Loire. Arch Mal Prof Environ. 2014;75:396–405. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Rijn R.M., Huisstede B.M.A., Koes B.W., Burdorf A. Associations between work-related factors and the carpal tunnel syndrome – a systematic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35:19–36. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roquelaure Y. Promoting a shared representation of workers' activities to improve integrated prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Saf Health Work. 2016;7:171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dimich-Ward H., Beking K., DyBuncio A., Chan-Yeung M., Du W., Karlen B., Camp P.G., Kennedy S.M. Occupational exposure influences on gender differences in respiratory health. Lung. 2012;190:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s00408-011-9344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.White G.E., Seaman C., Filios M.S., Mazurek J.M., Flattery J., Harrison R.J., Reilly M.J., Rosenmann K.D., Lumia M.E., Stephens A.C., Petcher E., Fizsimmons K., Davis L.K. Gender differences in work-related asthma: surveillance data from California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey, 1993–2008. J Asthma. 2014;51:691–702. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.903968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kennedy S.M., Koehoorn M. Exposure assessment in epidemiology: does gender matter? Am J Ind Med. 2003;44:576–583. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]