MKP1, a key regulator of environmental and biotic stress responses, is required for MAPK signaling in cell fate transition during guard cell differentiation.

Abstract

Stomata on the plant epidermis control gas and water exchange and are formed by MAPK-dependent processes. Although the contribution of MAP KINASE3 (MPK3) and MPK6 (MPK3/MPK6) to the control of stomatal patterning and differentiation in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) has been examined extensively, how they are inactivated and regulate distinct stages of stomatal development is unknown. Here, we identify a dual-specificity phosphatase, MAP KINASE PHOSPHATASE1 (MKP1), which promotes stomatal cell fate transition by controlling MAPK activation at the early stage of stomatal development. Loss of function of MKP1 creates clusters of small cells that fail to differentiate into stomata, resulting in the formation of patches of pavement cells. We show that MKP1 acts downstream of YODA (a MAPK kinase kinase) but upstream of MPK3/MPK6 in the stomatal signaling pathway and that MKP1 deficiency causes stomatal signal-induced MAPK hyperactivation in vivo. By expressing MKP1 in the three discrete cell types of stomatal lineage, we further identified that MKP1-mediated deactivation of MAPKs in early stomatal precursor cells directs cell fate transition leading to stomatal differentiation. Together, our data reveal the important role of MKP1 in controlling MAPK signaling specificity and cell fate decision during stomatal development.

Exploring molecular mechanisms that regulate cell fate and pattern formation is important in understanding the development of multicellular organisms. The development of stomata, which are generated through a series of discrete cell divisions and differentiation events, is highly flexible: it is easily adjusted by the interplay between the environmental and developmental factors affecting the growing plants in order to optimize gas exchange between the plants and the atmosphere. As such, stomatal development has been recognized as an excellent model for the study of these fundamental developmental processes.

In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), stomatal differentiation is directed by three basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors, SPEECHLESS (SPCH), MUTE, and FAMA, along with their partners SCREAM (SCRM) and SCRM2. They act as sequential switches for entry into the stomatal lineage, differentiation of meristemoids to guard mother cells (GMCs), and terminal differentiation of guard cells, respectively (Ohashi-Ito and Bergmann, 2006; MacAlister et al., 2007; Pillitteri et al., 2007; Kanaoka et al., 2008). To date, several signaling components that regulate stomatal development have been identified, and small regulatory networks have been proposed. Stomatal precursor cells emit peptide ligands EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR1 (EPF1) and EPF2, and they are perceived by cell-surface receptor complexes consisting of ERECTA-family receptor kinases (ERECTA, ERECTA-LIKE1 (ERL1), and ERL2) and TOO MANY MOUTHS (TMM) receptor-like protein (Nadeau and Sack, 2002; Shpak et al., 2005; Hara et al., 2007, 2009; Hunt and Gray, 2009; Lee et al., 2012). Although direct connections have not been established, these stomatal signals trigger activation of a downstream MAPK cascade, which negatively regulates stomatal development, likely by suppressing the activity of stomatal basic helix-loop-helixes (Bergmann et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2007; Lampard et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2015).

Reversible protein phosphorylation represents a major mechanism regulating cell signaling, and one important class of phosphorylation cascades in plants consists of the members of the MAPK cascades (MAPK Group, 2002; Colcombet and Hirt, 2008). A MAPK signaling module, composed of a YODA (YDA; a MAPK kinase kinase, MKK4/MKK5 (MAPK kinases (MAPKKs)), and MPK3/MPK6 (MAPKs), has been shown to play key roles in the regulation of stomatal development (Bergmann et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2007). Interestingly, the same MAPK components MPK3 and MPK6 are known to control several discrete stages of stomatal development, as well as other biological processes (Lampard et al., 2009; Andreasson and Ellis, 2010), but the underlying mechanisms of signaling specificity are largely unknown.

The magnitude and duration of MAPK activation are crucial in determining the physiological output of MAPK signaling (McClean et al., 2007). This highlights that a major point of regulation occurs at the level of the MAPK itself, which is determined by the activity of two counteracting enzymes, an upstream kinase (MAPKK) and a MAPK phosphatase (MKP). Consistent with its importance, deregulated MAPK signaling in all eukaryotes has been shown to drive a wide range of adverse effects (Dickinson and Keyse, 2006; Bartels et al., 2010). In contrast to upstream MAPKKs of MPK3/MPK6 (Wang et al., 2007; Lampard et al., 2009), the regulation by phosphatases during stomatal development remains unclear. In mammalian systems, some members of the dual-specificity phosphatases, which dephosphorylate both phospho-Ser/Thr and phosphotyrosine residues of their substrates, have been identified specifically as MKPs (Theodosiou and Ashworth, 2002). In Arabidopsis, five dual-specificity MKPs have been identified (Bartels et al., 2010), but their role in stomatal patterning and differentiation remain unknown at this stage.

In this report, we provide genetic and biochemical evidence to support MKP1, one of the five members of MKP gene family in Arabidopsis (Ulm et al., 2001; Bartels et al., 2010), as a key specificity regulator of MAPK signaling in controlling cell-fate transition during stomatal development. In the absence of MKP1, stomatal precursor cells fail to differentiate into stomata. MKP1 is preferentially expressed in the stomatal cell lineage in the epidermis, and specific expression of MKP1 in discrete stomatal lineage cell types demonstrates its function in promoting stomatal cell fate transition at the early stage of stomatal development. Consistent with our genetic study, in vivo biochemical assays further demonstrate that stomatal signal-induced MPK3/MPK6 phosphorylation is regulated by MKP1, indicating that they are the physiological substrates of MKP1 during stomatal development.

RESULTS

Identification of a Phosphatase That Controls Stomatal Development

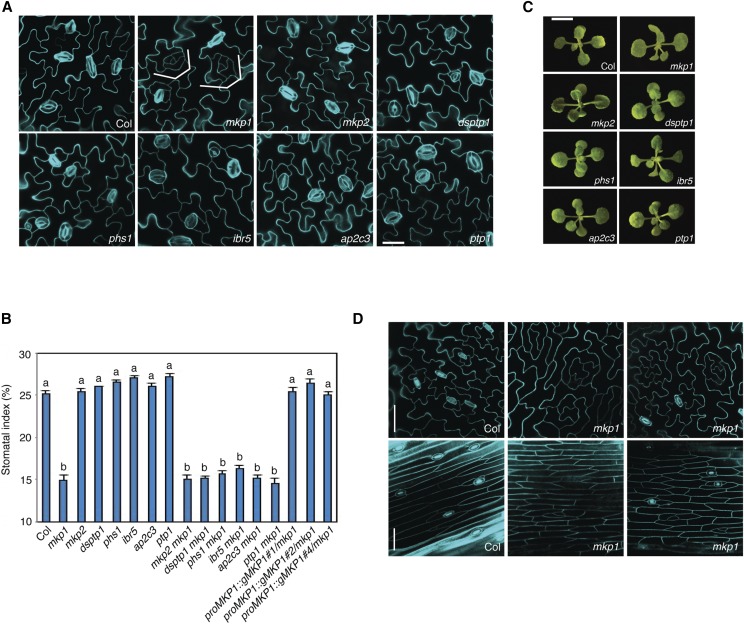

To identify phosphatase(s) that play a role in controlling stomatal development, we examined the number and distribution of stomata on the cotyledons of five dual-specificity MKP mutants (mkp1, mkp2, dual-specificity protein phosphatase1 [dsptp1], indole-3-butyric acid response5 [ibr5], and propyzamide-hypersensitive1 [phs1]; Kerk et al., 2002; Bartels et al., 2010). We also checked stomatal phenotypes of the Tyr phosphatase, PROTEIN TYR PHOSPHATASE1 (PTP1) and the Ser/Thr phosphatase, ARABIDOPSIS PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE2C (AP2C3) mutants since they control stomatal MAPKs, MPK3, and/or MPK6 activity (Gupta and Luan, 2003; Bartels et al., 2010; Brock et al., 2010). As shown in Figure 1, we observed that the mkp1 mutants display a statistically significant reduction (P < 0.05, ANOVA) in stomatal index (number of stomata per total number of epidermal cells) compared with wild type and each of the other phosphatase mutants at the early stage of development when growth phenotypes of mutants are indistinguishable from that of the wild type. The epidermis of mkp1 seedlings developed clusters of small cells that failed to differentiate into stomata (brackets in Fig, 1A). As the cotyledons grow, these cells elongate and may result in the formation of stomatal-lineage ground cell (SLGC)-like clusters, which eventually expand and differentiate into lobed pavement cells (Supplemental Fig. S1). These stomatal phenotypes of mkp1 were also found in other mature organs that normally produce stomata, including leaves and stems (Fig. 1D). Next, we generated all combinations of higher-order mutants to uncover possible redundant roles of MKP1 with other MKPs as well as with PTP1 and AP2C3. The number of stomata in all double mutants was similar to the mkp1 single mutant, indicating a major and specific role of MKP1 in controlling stomatal development (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

MKP1 positively regulates stomatal development. A, Representative confocal images of 10-d-old abaxial cotyledons of the following genotypes: wild type (Col), mkp1, mkp2, dsptp1, phs1, ibr5, ap2c3, and ptp1. The mkp1 single mutant, but not other phosphatase mutants, showed stomatal development defects, including fewer stomata and islands of small arrested cells, indicated by brackets. Cells were outlined by propidium iodide staining (cyan), and images were taken under the same magnification. Scale bar, 30 µm. B, Quantitative analysis of 10-d-old abaxial cotyledon epidermis. Stomatal index (SI) of phosphatase single mutants, double mutants, and three independent complemented lines expressed as the percentage of the number of stomata to the total number of epidermal cells. Genotypes with nonsignificantly different phenotypes were grouped together with the same letter (P < 0.05, Tukey’s HSD test after one-way ANOVA). n = 14 to 15 for each genotype. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Bars, means. Error bars, se. C, The growth phenotypes of 2-week-old seedlings of indicated genotypes grown on 0.5× MS plates. Scale bar in Col, 0.5 cm, and others are at the same scale. The representative images were selected from at least five replicates. D, Representative confocal images of 5-week-old abaxial rosette leaf (top) and 7-week-old stem epidermis (bottom) from Col and mkp1. Cells were outlined by propidium iodide staining (cyan), and images were taken under the same magnification. Scale bars, 50 µm.

To determine whether the inhibited stomatal development in mkp1 mutant is caused by the loss of MKP1, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing MKP1 in the mkp1 mutant background under its own native promoter for complementation analysis. Stomatal development in these transgenic lines was fully restored to that observed in the wild type, suggesting that fewer stomata and more nonstomatal cells found in mkp1 plants are complemented by the MKP1 transgene (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S3).

To further determine whether the phosphatase activity of MKP1 is required for its function in stomatal development, we substituted a Ser residue for a conserved Cys residue (C235) in the catalytic active site (VXVHCX2GXSRSX5AYLM) of canonical dual-specificity phosphatases that is well known to be essential for phosphatase activity. Transgenic lines were generated to express MKP1C235S in the mkp1 background under its own promoter. Analysis of three independent transgenic lines showed that they generate similar stomatal developmental defects, as does mkp1, indicating that the phosphatase activity of MKP1 is necessary for its regulation of stomatal development (Supplemental Fig. S4). Taken all together, our data indicate that MKP1 acts as a positive regulator, and the phosphatase activity of MKP1 is required for its function in stomatal development.

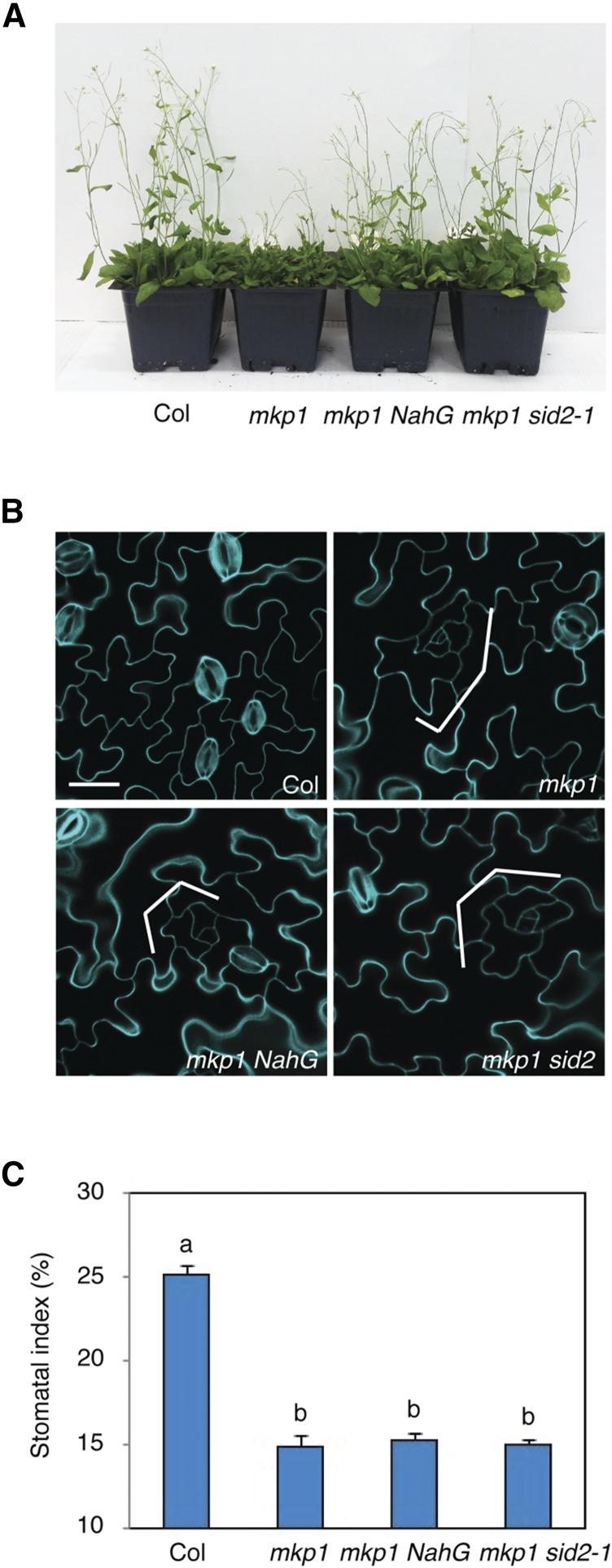

The mkp1 Stomatal Phenotype Is Independent of the Elevated Salicylic Acid Levels in mkp1

Although the growth of mkp1 mutants is indistinguishable from the wild type, we were able to detect obvious stomatal defects in mkp1 (Fig. 1). Next, we further tested phenotypes of salicylic acid (SA)-deficient mutants in the mkp1 background to fully rule out the possibility that the stomatal phenotype of mkp1 is associated with its previously described SA-related pleiotropic growth phenotypes (Bartels et al., 2009). Expression of a bacterial NahG gene encoding salicylate hydroxylase that degrades SA in planta (Gaffney et al., 1993), as well as introduction of salicylic acid induction deficient2 (sid2), which are not able to synthesize SA (Wildermuth et al., 2001), dramatically reverted the defense-related growth defects of mkp1 (Fig. 2A). However, a substantial decrease in stomata number with arrested small cell clusters was still found in both mkp1 NahG and mkp1 sid2-1 double mutants, comparable to that of the mkp1 single mutant (Fig. 2, B and C). These data clearly indicate that the role of MKP1 in stomatal development is independent of the elevated SA and defense responses.

Figure 2.

Elevated salicylic acid levels are not responsible for the stomatal phenotype of mkp1. A, Five-week-old plants of wild type (Col), mkp1, mkp1 nahG, and mkp1 sid2. B, Representative confocal images of 10-d-old abaxial cotyledons of wild type, mkp1, mkp1 NahG, and mkp1 sid2 mutants. Both mkp1 nahG and mkp1 sid2 mutants exhibit stomatal development defects (significant reduction of stomata and islands of small arrested cells, indicated by brackets) similar to those of the mkp1 single mutant. Cells were outlined by propidium iodide staining (cyan), and images were taken under the same magnification. Scale bar, 30 µm. C, Stomatal index (SI) of the cotyledon abaxial epidermis from 10-d-old seedlings of Col, mkp1, mkp1 NahG, and mkp1 sid2 mutants, expressed as the percentage of the number of stomata to the total number of epidermal cells. Genotypes with nonsignificantly different phenotypes were grouped together with a letter (P < 0.05, Tukey’s HSD test after one-way ANOVA). n = 14 to 15 for each genotype. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Bars, means. Error bars, se.

MKP1 Promotes the Stomatal Cell Fate Differentiation

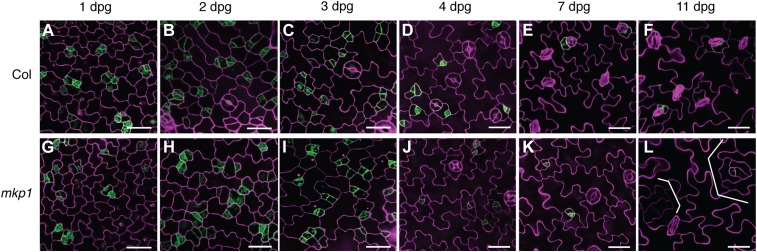

To determine how significantly fewer stomata with small cell clusters are generated in the mkp1 mutants, we examined the epidermal development process in wild type and the mkp1 mutants at different times after germination using the stomatal cell-type-specific marker proTMM::GUS-GFP. TMM expresses in early stomatal-lineage cells, including meristemoid mother cells (MMCs), meristemoids, and GMCs, and has lower expression in SLGCs and mature guard cells (Fig. 3). Epidermal development and GFP signals in mkp1 seedlings showed no differences from those in the wild type at 1 d postgermination (dpg). This indicates that stomatal developmental defects in the mkp1 seedlings are likely to be postembryonic. At 2 and 3 dpg, asymmetric cell divisions, characteristic of entry into the stomatal pathway, occurred, and GFP-positive cells were evenly dispersed in both the wild-type and mkp1 epidermis (Fig. 3, B, C, H, and I). However, meristemoids produced by asymmetric cell divisions and expressing proTMM::GUS-GFP were frequently arrested and unable to proceed to differentiate into stomata in the mkp1 epidermis (Fig. 3, D–F and J–L). At 11 dpg, the mkp1 epidermis had a dramatically reduced number of stomata, with patches of SLGCs becoming the lobed pavement cells (Fig. 3, F and L). Faint GFP signals were exhibited at the center of one of the SLGC patches, suggesting that they all have stomatal cell identity at the beginning but eventually differentiate into SLGCs and pavement cells.

Figure 3.

Time-course analysis of epidermal development in mkp1. Confocal images of the abaxial epidermis of wild-type and mkp1 cotyledons. mkp1 seedlings conferred an epidermal phenotype with arrested stomatal precursors, resulting in suppression of stomatal cell fate and formations of expanded SLGC-like clusters becoming lobed pavement cells (brackets). proTMM::GUS-GFP (green) was used to monitor stomatal lineage cells. The representative images were selected from at least five replicates. Scale bars, 30 µm. A to F, Wild-type epidermis at 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 11 dpg, respectively. G to L, mkp1 epidermis at 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 11 dpg, respectively.

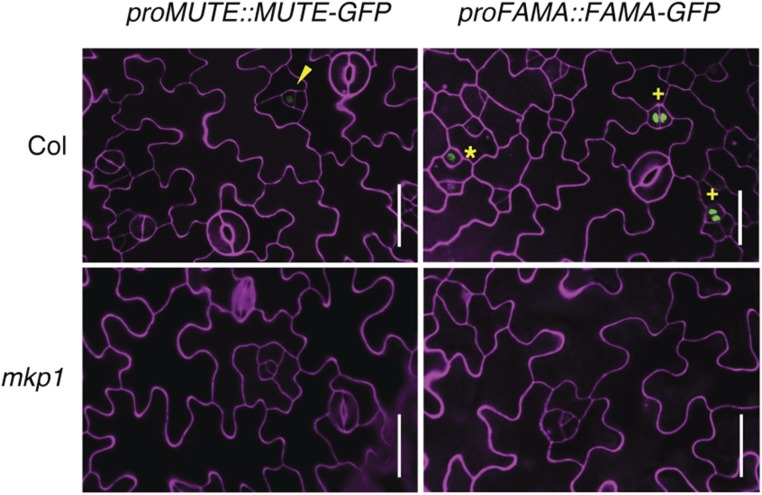

To further investigate whether arrested meristemoids progress into GMCs, we next examined the expression of proFAMA::FAMA-GFP, a translational fusion of GFP and FAMA. No expression was detected in the mkp1 epidermis of proFAMA::FAMA-GFP, which is normally expressed in GMCs and young guard cells (Fig. 4, right; Ohashi-Ito and Bergmann, 2006). Likewise, no proMUTE::MUTE-GFP, which normally marks mature meristemoids, which have undergone several divisions, was expressed in the arrested small cells of mkp1 (Fig. 4, left; Supplemental Fig. S5). This indicates that meristemoids that initially form in mkp1 do not progress to either late meristemoids or GMCs. Combined, these observations indicate that MKP1 may promote stomatal differentiation by controlling the commitment of meristemoids to a stomatal cell fate after the asymmetric cell division events during stomatal development.

Figure 4.

Expression of stomatal cell lineage markers in mkp1. Confocal images of abaxial cotyledon epidermis of wild-type (3–5 dpg, top) and mkp1 (10–11 dpg, bottom) seedlings carrying the translational fusion of proMUTE::MUTE-GFP (left) and proFAMA::FAMA-GFP (right). Mature meristemoids are indicated by arrowheads, GMCs by asterisks, and immature guard cells by plus signs. At least three transgenic lines for each construct were used, and similar results were obtained. The representative images were selected from at least five replicates. Scale bar, 30 µm.

MKP1 Acts Downstream of YDA and Upstream of MPK3/MPK6 to Regulate Stomatal Development

To place MKP1 within the context of the known signaling pathways for stomatal patterning and differentiation, we produced various double mutant plants by crossing mkp1 with known stomatal mutants. As shown in Figure 5, A to F, loss of MKP1 dramatically suppressed the stomatal clustering phenotype of tmm, er erl1 erl2, and yda mutants. This indicates either that MKP1 acts downstream of the receptor proteins ERECTA family and TMM and the first player in the stomatal MAPK signaling cascade (YDA) or that they function independently in the same stomatal lineage cells to regulate stomatal development. Notably, the loss of MKP1 was also able to rescue other various growth and developmental defect phenotypes of yda plants (Supplemental Fig. S6). This suggests that target(s) of MKP1 could be the downstream components of YDA in multiple growth and developmental pathways.

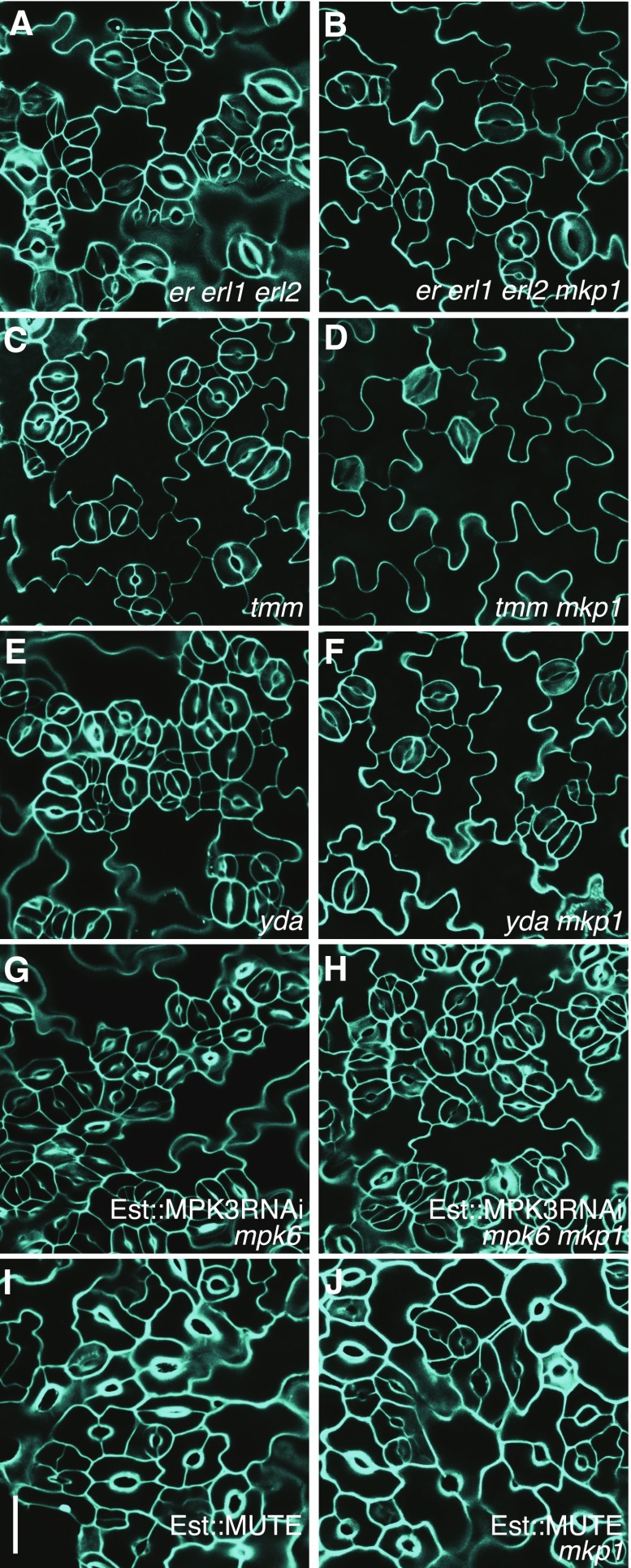

Figure 5.

MKP1 acts downstream of ERECTA family members, TMM, and YDA but upstream of MPK3 and MPK6 in the stomatal development signaling pathway. A to J, Confocal images of abaxial cotyledon epidermis from 7-d-old seedlings of the following genotypes: er erl1 erl2 (A), er erl1 erl2 mkp1 (B), tmm (C), tmm mkp1 (D), yda (E), yda mkp1 (F), induced Est::MPK3RNAi in mpk6 (G), induced Est::MPK3RNAi in mpk6 mkp1 (H), induced Est::MUTE (I), and induced Est::MUTE in mkp1 background (J). At least three transgenic lines for each construct in G to J were used, and similar results were obtained. The representative images were selected from at least five replicates. Scale bar, 30 µm.

Two Arabidopsis MAPKs, MPK3 and MPK6, genetically act downstream of YDA to control stomatal patterning and differentiation (Wang et al., 2007). Although mpk3 mkp1 and mpk6 mkp1 double mutants significantly improve SA-related growth defects of mkp1 (Bartels et al., 2009), there were no obvious differences found on the epidermal phenotype of mpk3 mkp1 and mpk6 mkp1 mutants compared to that of mkp1 (Supplemental Fig. S7). This is consistent with MPK3 and MPK6 functioning redundantly in the regulation of stomatal development. Thus, to both examine functional relationships between MKP1 and these two MAPKs and circumvent embryonic lethality of the mkp3 mpk6 double mutant (Wang et al., 2007), we generated an MPK3 RNAi construct under the regulation of an estradiol-induction system and transformed the construct into mpk6 and mpk6 mkp1 mutant backgrounds, respectively. As shown in Figure 5, G and H, the overall stomatal phenotypes of MPK3RNAi mpk6 mkp1 are identical to those of MPK3RNAi mpk6 with estradiol induction. These results indicate that MPK3RNAi mpk6 is epistatic to mkp1, consistent with the predicted function of MKP1 as a MAPK phosphatase, and both MPK3 and MPK6 could be the substrates of MKP1. Next, we introduced a construct expressing estradiol-inducible MUTE acting downstream of the stomatal MAPK cascade into the wild-type and mkp1 backgrounds and found that mkp1 did not have any effect on the phenotypes of MUTE overexpression lines, indicating MUTE is also epistatic to MKP1 (Fig. 5, I and J). Taken together, these data strongly indicate that MKP1 acts downstream of the ERECTA family, TMM, and YDA, but upstream of the stomatal MAP kinases, MPK3 and MPK6, in the stomatal development pathway.

MPK3 and MPK6 Are Hyperactivated by a Stomatal Peptide Signal in mkp1

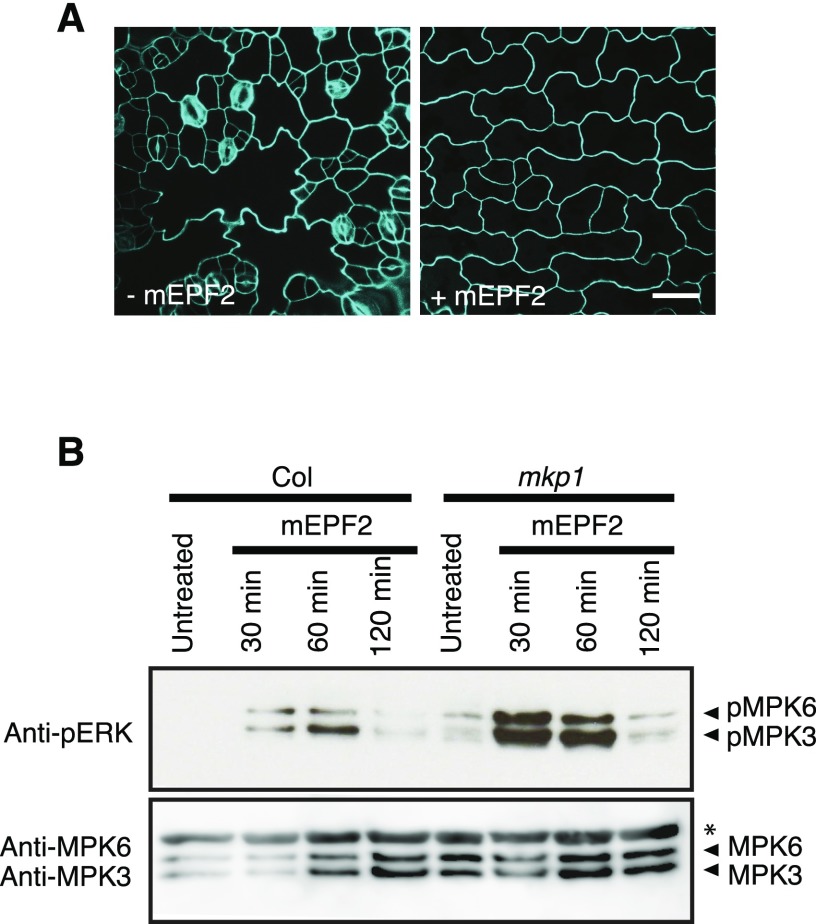

Our genetic analysis suggests that MPK3 and MPK6 are the substrates of MKP1 during stomatal development. Using the bioactive, mature EPF2 (mEPF2) peptide that elicits a unique stomatal developmental response, it was recently shown that recognition of the stomatal peptide EPF2 by its receptor triggers rapid MAPK activation to inhibit stomatal development (Lee et al., 2015). Thus, to address if MPK3 and MPK6 are the substrates of MKP1 in the context of stomatal development, we first produced a recombinant mEPF2 peptide and subsequently tested whether MAPK activation induced by the stomatal signal is affected by the loss of MKP1 using the pERK antibody that recognizes only the phosphorylated and active MAPK forms. As shown in Figure 6, application of mEPF2 peptide to Arabidopsis wild-type seedlings rapidly elicited phosphorylation of MPK3 and MPK6, which is consistent with a previous report (Lee et al., 2015). In mkp1 seedlings, the phosphorylation levels of these MAPKs were higher than those in the wild-type seedlings, demonstrating MKP1 as a negative regulator of stomatal MAPKs, MPK3 and MPK6, in vivo. The difference seems more pronounced within 30 min after the seedlings were treated with mEPF2 peptide.

Figure 6.

EPF2 triggers MAPK hyperactivation in mkp1 seedlings. A, Confocal images of the abaxial epidermis of cotyledons of epf2 seedlings grown with or without 2 µm mature EPF2 peptide (mEPF2) treatment. Peptide application experiments were performed at least three times. Scale bar, 30 µm. B, Seedlings of wild type (Col) and mkp1 treated with mEPF2 (1 µm) for the indicated time periods. Activated MAPKs were detected in the Col and mkp1 seedlings by the immunoblots using antipERK antibody (top). The blots were reprobed with anti-MPK3 and MPK6 antibodies to detect MPK3 and MPK6 protein levels on the same samples (bottom). The asterisk indicates a nonspecific band. The molecular weights of MPK3 and MPK6 proteins detected using anti-MPK3 and MPK6 antibodies were consistent with the activated MAPKs (top), suggesting that they are likely MPK3 and MPK6 activated by mEPF2. Experiments were conducted more than three times with similar results, and representative data from one such experiment are shown.

In summary, this result indicated that MKP1 positively regulates stomatal development by inhibiting the activities of MPK3 and MPK6, which likely leads to suppression of downstream transcription factors specifying stomatal differentiation.

MKP1 Controls the Activity of MAPKs in Early Stomatal Lineage Cells

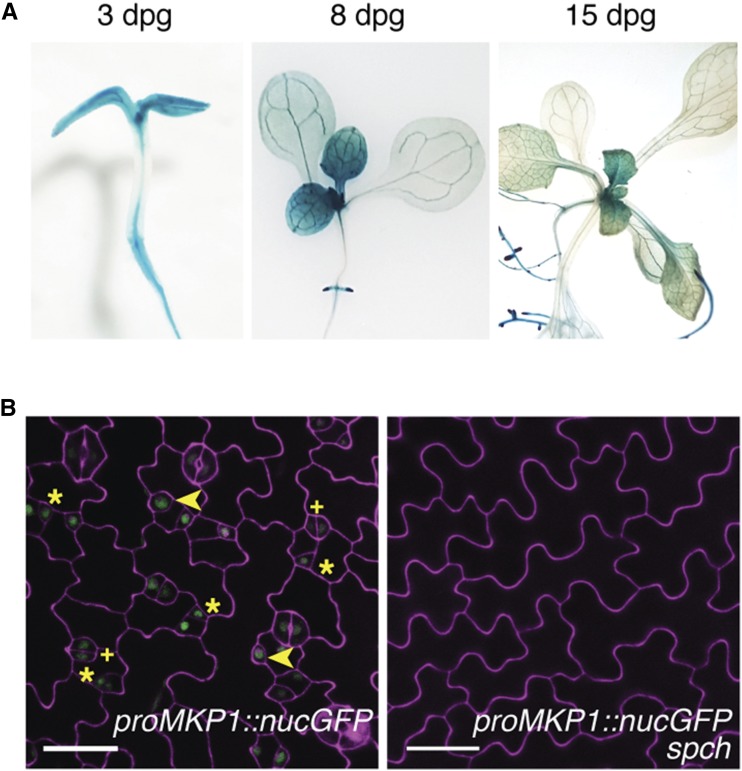

The demonstration that MKP1 is involved in the regulation of stomatal development predicts that MKP1 may be expressed in stomatal lineage cells. To test this possibility, we created transcriptional reporters for MKP1 using the 2.7-kb 5′ sequence driving both GUS (proMKP1::GUS) and GFP (proMKP1::nucGFP). Strong GUS activity in proMKP1::GUS lines was observed in developing cotyledons and leaves, consistent with the fact that stomatal development starts in immature organs (Fig. 7A). Analysis of MKP1 expression in the developing cotyledon epidermis of proMKP1::nucGFP lines further showed MKP1 promoter activity in the early stomatal lineage cells, including meristemoids, GMCs, SLGCs, and young guard cells, but very weak or no activity in mature stomata and pavement cells (Fig. 7B, left). Promoter activity of MKP1 was not detected in the spch seedling epidermis, which lacks all stomatal lineage cells in the epidermis (Fig. 7B, right). This observation further confirms the stomatal-lineage-specific expression of MKP1 and indicates that SPCH is required for the expression of MKP1 in the stomatal lineage cells.

Figure 7.

Expression patterns of MKP1. A, proMKP1::GUS expression (blue) at 3, 8, and 15 dpg. B, Confocal image of proMKP1::nucGFP (green) in developing wild-type and spch abaxial cotyledon epidermis. Meristemoids are indicated by asterisks, GMCs by arrowheads, and immature guard cells by plus signs. At least three transgenic lines for each construct were used, and similar results were obtained. The representative images were selected from at least five replicates. Scale bars, 30 µm.

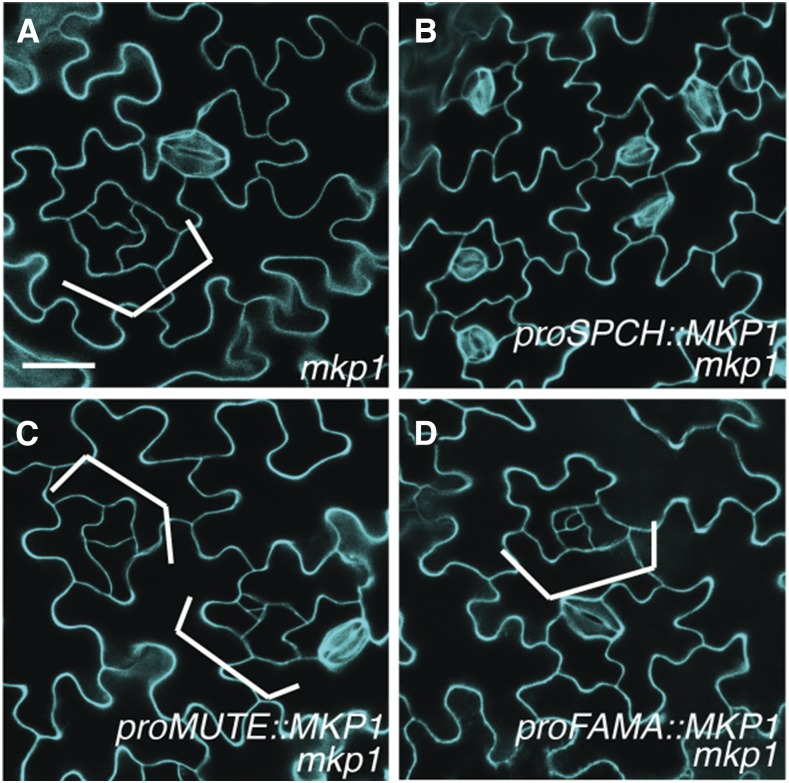

To determine whether MKP1 expression in particular stages of the stomatal lineage is important for stomatal development, we next performed in vivo stomatal cell-type-specific rescue experiments. We initiated the expression of MKP1 in distinct, different stages of the stomatal lineage, MMCs, mature meristemoids, and GMCs, by introducing MKP1-GFP transgene under the control of well-studied stomatal lineage-specific SPCH, MUTE, or FAMA promoters into mkp1 mutants. Each transgene expression was verified by the appearance of GFP fluorescence in the appropriate, discrete stomatal lineage cells (Supplemental Fig. S8). As shown in Figure 8B, mkp1 plants expressing proSPCH::MKP1, which leading MKP1 expression beginning in MMCs, were able to fully rescue the stomatal developmental defect of mkp1. In contrast, either proMUTE::MKP1 or proFAMA::MKP1, allowing MKP1 expression in late meristemoids, which had already undergone a few rounds of asymmetric division, and GMCs, respectively, had no phenotypic effects on the mkp1 seedling epidermis (Fig. 8, C and D). Thus, we conclude that the expression of MKP1 in the MMCs and young meristemoids is sufficient to rescue stomatal phenotype of mkp1, and this suggests that MKP1 plays an important role in controlling MAPK activity in these early stomatal lineage cell types for proper stomatal cell fate differentiation.

Figure 8.

Early stomatal-cell-specific expression of MKP1 is sufficient for restoring normal stomatal development. A to D, Confocal images of abaxial cotyledon epidermis from 10-d-old seedlings of mkp1 (A), mkp1 expressing proSPCH::MKP1 (B), proMUTE::MKP1 (C), and proFAMA::MKP1 (D). Brackets indicate small cell clusters with arrested or dedifferentiated meristemoids. At least three transgenic lines for each construct in B to D were used, and similar results were obtained. The representative images were selected from at least five replicates and images were taken under the same magnification. Scale bar, 30 µm.

DISCUSSION

Differences in the duration and magnitude of MAPK activation is a crucial determinant of the biological outcome(s) controlled by these kinases (McClean et al., 2007). This indicates the importance of negative regulators of MAPK signaling to determine MAPK activity for proper signaling outputs. In plants, activation of MAPK cascades has been known to associate with a wide range of environmental and developmental responses, but relatively little is known about the corresponding MAPK deactivation processes. Here, we present genetic and biochemical evidence that MKP1 positively regulates stomatal differentiation by inhibiting phosphorylation of MPK3 and MPK6 in early stomatal lineage cells. Our findings highlight the importance of fine-turning the balance of MAPK activity mediated by a phosphatase in controlling plant MAPK signaling specificity and coordinated stomatal cell fate decision in Arabidopsis.

MAPK inactivation in eukaryotes can be achieved by different classes of protein phosphatases; the fact that MAPK activation is achieved by dual phosphorylation on both Thr and Tyr residues indicates that major negative regulators of MAPKs are a subgroup of the dual-specificity MKPs (Dickinson and Keyse, 2006). In Arabidopsis, five dual-specificity MKPs have been identified (Bartels et al., 2010), but their role in plant growth and development has not yet been investigated. Starting from in vivo functional screening of all five Arabidopsis MKPs as well as PTP1 and AP2C3 known to control activity of MPK3 and/or MPK6 (Gupta and Luan, 2003; Bartels et al., 2010; Brock et al., 2010), we discovered that dual-specificity phosphatase MKP1, known to control various environmental stress responses (Ulm et al., 2001, 2002; González Besteiro et al., 2011; González Besteiro and Ulm, 2013; Li et al., 2017), plays an important role in stomatal development. The specific role of MKP1 in stomatal lineage was confirmed by multiple experiments: (1) the additional introduction of ptp1 in the double mutant ptp1 mkp1 did not affect the epidermal phenotype of mkp1 in contrast to their redundant function in SA biosynthesis and with the profound SA-related growth phenotypes (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S2); (2) mkp1 with mutants compromised in SA accumulation complement mkp1’s pleiotropic growth phenotype but not stomatal defects (Fig. 2); (3) MKP1 is preferentially expressed in stomatal-lineage cell types in the epidermis (Fig. 7B); (4) when MKP1 is specifically expressed in MMCs and early meristemoids, the stomatal phenotype of mkp1 is fully rescued (Fig. 8).

Although the activation of MPK3 and MPK6 is substantially affected in EPF2-treated mkp1 seedlings, it is clear that the inactivation process is not completely blocked (Fig. 6B). This might indicate that other protein phosphatases can participate in dephosphorylation of these two MAPKs. The same MAPK components, such as MKK4/MKK5 and MPK3/MPK6, control discrete stages of stomatal development, and based on our study, we likely found a phosphatase required for the particular developmental progression from one precursor cell (meristemoid) to another (GMC), which is just one aspect of the stomatal developmental process. Therefore, we speculate that additional phosphatases are contributing to the specificity of MAPK signaling during stomatal development.

AP2C3 has been identified as another Ser/Thr phosphatase that could control MAPK signaling in stomatal development. AP2C3 is expressed in the stomatal lineage from late meristemoids onward, and ectopic overexpression results in the stomatal clustering phenotype (Umbrasaite et al., 2010). However, neither the ap2c3 single mutant nor higher-order mutants with related phosphatases conferred a visible stomatal phenotype (Umbrasaite et al., 2010). To uncover a possible redundant role between MKP1 and AP2C3, we created the ap2c3 mkp1 double mutant (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S2), but no phenotypic difference was detected compared with that of mkp1. AP2C3 has additional roles in various stress responses, including stomata physiology (Brock et al., 2010). Thus, further work is required to dissect the role of AP2C3 in stomatal development. Similar approaches used here, including in vivo biochemical analysis in the context of stomatal development and stomatal lineage cell-type-specific analysis, would be informative. Nevertheless, it is likely that MKP1 and AP2C3 regulate activity of stomatal MAPKs, acting in different stages of stomatal lineage for the tight control of different aspects of stomatal development.

MKP1 could control the function of stomatal MAPKs for inhibiting the asymmetric cell division of MMCs and meristemoids or stomatal cell fate specification of the progeny cells of asymmetric cell divisions. Our time course analysis of epidermal development in mkp1 seedlings shows that initial asymmetric cell divisions, characteristic of entry into the stomatal pathway to produce “first” stomatal precursor cells (meristemoids), occurred without any differences from those in the wild type (Fig. 3, A–D and G–J). However, we recognized that some of the early meristemoids that initially form in the mkp1 epidermis are arrested and unable to differentiate into stomata in a later stage of development (Figs. 3, E, F, K, and L, and 4). These data suggest that MKP1 controls the commitment of meristemoids to a stomatal cell fate after initial asymmetric cell division events during stomatal development. Consistent with this idea, despite the fact that mkp1 displays variability in the strength of the epidermal phenotype (from no stomata to reduced stomata), loss of MKP1 always causes the formation of patches of small pavement cells (Fig. 1D; Supplemental Fig. S1). Pavement cells are directly differentiated either from protodermal cells or from stomatal lineage. Those pavement cells derived from protodermal cells are larger than those derived from stomatal lineage. Therefore, patches of small pavement cells found in mkp1 are generated from stomatal lineage after asymmetric cell divisions and are not differentiated directly from protodermal cells (a process that creates larger pavement cells). This suggests that the specific action of MKP1 is the regulation of differentiation rather than the production of stomatal lineage cells during stomatal development. Together, our work reveals a previously unanticipated role of a MKP1: it selectively affects stomatal MAPK activity in specific stomatal lineage cell types to regulate stomatal cell fate decision. This highlights the importance of spatially restricted MKP activity in determining the physiological outcome of complex MAPK signaling in plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Columbia (Col) was used as the wild type. The mutants dsptp1-1 (SALK_092811), phs1-5 (SALK_070121), ibr5-3 (SALK_039359), ap2c3 (SALK_109986), ptp1-1 (SALK_118658), and mpk6-2 (SALK_073907) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. The mutants mkp1, mkp1 mpk3-1, mkp1 mpk6-2, mkp1 NahG, sid2-1, mkp2-1, epf2-1, er105 erl1-2 erl2-1, tmm-KO, yda-2, and spch-3, and the transgenic plants of proTMM::GUS-GFP, Est::MUTE, proMUTE::MUTE-GFP, and proFAMA::FAMA-GFP were described previously (Wildermuth et al., 2001; Nadeau and Sack, 2002; Lukowitz et al., 2004; Shpak et al., 2005; Pillitteri et al., 2007; Bartels et al., 2009; Lumbreras et al., 2010; Horst et al., 2015; Qi et al., 2017). The mkp1 high-order mutants and each transgenic plant in the background of Col and various mutants, were generated by either Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation or genetic crosses. Genotypes were verified by a PCR-based genotyping method using the primers listed in Supplemental Table S1. Arabidopsis seeds were sterilized with 33% (v/v) bleach and plated on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog (MS) agar plates. When needed, 10-d-old seedlings were transferred to soil and grown at 22°C under long-day conditions (18 h light/6 h dark).

Plasmid Construction and Generation of Transgenic Plants

The following plasmids were constructed to generate transgenic plants: pJSL35 (MPK3 cDNA sense), pJSL36 (MPK3 cDNA antisense), pLGC22 (MPK3RNAi), pLGC23 (Est::MPK3RNAi), pJSL118 (MKP1 promoter), pJSL122 (proMKP1::GUS), pJSL123 (proMKP1::nucGFP), pJSL18 (MKP1 genomic sequence), pJSL120 (proMKP1::gMKP1), pHD1 (MKP1 genomic sequence with C235S mutation), pJSL126 (proMKP1::gMKP1C235S), pLGC9 (MKP1 cDNA with no stop codon), pJSL117 (proSPCH::MKP1-GFP), pJSL119 (proMUTE::MKP1-GFP), and pJSL121 (proFAMA::MKP1-GFP). Plant binary vectors based on Gateway cloning technology (Invitrogen) were used for most cloning except the Est::MPK3RNAi construct. For silencing of MPK3 by dsRNA, sense and antisense products targeting the N-terminal region (1 to 693 bp) of MPK3 were inserted into the XhoI/SpeI sites of the pER8 vector (Zuo et al., 2000), which placed the RNAi construct under the control of the estradiol-inducible promoter, as described previously with minor modifications (Lee and Ellis, 2007). See Supplemental Tables S1 and S2 for primers used and detailed information about each plasmid. Arabidopsis transgenic plants were generated using A. tumefaciens (strain GV3101)-mediated transformation by the floral-dipping method (Clough and Bent, 1998). At least 20 independent T1 plants per construct were screened, and three T2 or T3 lines with a single insertion were subjected to detailed phenotypic characterization.

Confocal Microscopy

A Nikon C2 operated by NIS-Elements (Nikon) was used to capture propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) staining to visualize cell outlines and GFP fluorescence images (excitation 561 nm, a 561-nm long-pass emission filter was used for propidium iodide (PI); excitation 488 nm, a 525/50-nm bandpass emission filter was used for GFP). All imaging processing was performed with Fiji software, and the images were false colored using Photoshop CS6 (Adobe).

Quantitative Analysis of Stomatal Phenotype

For quantitative analysis, the central area of abaxial cotyledons of 10-d-old seedlings of respective genotypes were stained with toluidine blue O (Sigma-Aldrich) as reported previously (Lee et al., 2012), and images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse TiE equipped with a DsRi2 digital camera (Nikon). Stomatal index was quantified as the percentage of the number of stomata to the total number of epidermal cells using toluidine blue O-stained epidermal samples. The statistically significant differences in a panel of different genotypes were determined by Tukey’s HSD test after a one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05) and are indicated by different letters.

Chemical Treatments

Transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings carrying estradiol-inducible MUTE and MPK3RNAi constructs in the background of Col and various mutants were germinated on 0.5× MS medium in the absence or presence of 10 μm estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich). The induction was confirmed by observing the epidermal phenotypes of cotyledons using a confocal microscope.

GUS Reporter Assays

GUS staining was performed according to a previous report (Malamy and Benfey, 1997) with some modifications. In brief, seedlings were prefixed with 90% (v/v) acetone at −20°C, and then washed twice with GUS reaction buffer without X-GlcA (0.2% [v/v] Triton-100, 10 mm potassium ferricyanide, and 10 mm potassium ferrocyanide in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) before staining samples in the same GUS reaction buffer with 1 mg/mL X-GlcA at 37°C for 10 to 12 h Following staining, tissues went through an ethanol series in which samples were incubated successively in 30, 50, and 70% ethanol at room temperature for 30 min each and then stored in 95% ethanol until observing tissues under the microscope. Reported expression patterns were observed in at least three independent lines.

Production of Recombinant EPF2 Peptide and Bioassays

Expression, purification, and refolding of EPF2 peptides were performed as described previously (Lee et al., 2012). For bioassays, either buffer alone (mock, 50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.0) or EPF2 peptide (1 μm) in buffer were applied to epf2 seedlings in 0.5× MS liquid medium transferred after being grown for 1 d on 0.5× MS media plates. After 5 d of further incubation, stomatal phenotypes of abaxial cotyledons were examined with confocal microscopy prior to performing MAPK activity assays. Arabidopsis epf2 seedlings that conferred increased epidermal cell density (Hara et al., 2009) were used for verification of the bioactivity of the EPF2 peptide.

MAPK Phosphorylation Assays

Twelve-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings of Col and mkp1, grown for 5 d on 0.5× MS media plates and then transferred to 0.5× MS liquid media, were used for EPF2 peptide-triggered MAPK activation assays. Treatment with peptide was carried out by adding bioactive EPF2 peptide (2 μm), and tissue samples were harvested at the indicated times. Total protein was extracted by grinding samples in extraction buffer (100 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mm EDTA, 5 mm EGTA, 2 mm DTT, 10 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm NaF, 50 mm β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mm PMSF, 1 tablet per 50-mL extraction buffer of proteinase inhibitor mixture, 10% glycerol, 7.5% [w/v] polyvinylpolypyrrolidone), and the protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) with BSA as a standard. Immunoblot analysis was performed using the antipERK antibody (1:4,000; New England Biolabs). After the phosphorylated MAP kinases were detected, the immunoblot membrane was incubated in a stripping buffer (100 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) and reprobed with the anti-AtMPK3 (1:1,000; Sigma-Aldrich) and anti-AtMPK6 (1:1,000; Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies to detect the MPK3 and MPK6 protein levels. Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (1:20,000; Cell signaling) was used as secondary antibody.

Accession Numbers

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative identifiers for the genes mentioned in this article are as follows: MKP1 (At3g55270), MKP2 (At3g06110), DsPTP1 (At3g23610), IBR5 (At2g04550), PHS1 (At5g23720), PTP1 (At1g71860), AP2C3 (At2g40180), YDA (At1g63700), MPK3 (At3g45640), MPK6 (At2g43790), SID2 (At1g74710), EPF2 (At1g34245), ER (At2g26330), ERL1 (At5g62230), ERL2 (At5g07180), TMM (At1g80080), SPCH (At5g53210), MUTE (At3g06120), and FAMA (At3g24140).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Mature cotyledon epidermal phenotypes of mkp1.

Supplemental Figure S2. Stomatal phenotype of mkp1 and higher-order mutants in closely related phosphatases.

Supplemental Figure S3. Complementation of mkp1 loss-of-function mutants by MKP1.

Supplemental Figure S4. A conserved Cys (C235) of MKP1 is required for its function in stomatal development.

Supplemental Figure S5. Expression of a stomatal cell lineage marker in mkp1.

Supplemental Figure S6. mkp1 rescues the pleiotropic growth defects in yda.

Supplemental Figure S7. Effects of mpk3 and mpk6 mutations on stomatal development in mkp1.

Supplemental Figure S8. Verification of expression of MKP1 under the control of distinct stomatal lineage-specific promoters used in this study.

Supplemental Table S1. List of primers and their DNA sequence used in this study.

Supplemental Table S2. List of plasmids constructed in this study.

Dive Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

Acknowledgments

We thank Keiko Torii, Jacqueline Monaghan, and Roman Ulm and the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center for various Arabidopsis mutant and transgenic seeds; Longgang Cui for generating the estradiol-inducible MPK3RNAi construct; and Patrick Gulick and William Zerges (Concordia University) for commenting on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Andreasson E, Ellis B (2010) Convergence and specificity in the Arabidopsis MAPK nexus. Trends Plant Sci 15: 106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels S, Anderson JC, González Besteiro MA, Carreri A, Hirt H, Buchala A, Métraux JP, Peck SC, Ulm R (2009) MAP kinase phosphatase1 and protein tyrosine phosphatase1 are repressors of salicylic acid synthesis and SNC1-mediated responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 2884–2897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels S, González Besteiro MA, Lang D, Ulm R (2010) Emerging functions for plant MAP kinase phosphatases. Trends Plant Sci 15: 322–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann DC, Lukowitz W, Somerville CR (2004) Stomatal development and pattern controlled by a MAPKK kinase. Science 304: 1494–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock AK, Willmann R, Kolb D, Grefen L, Lajunen HM, Bethke G, Lee J, Nürnberger T, Gust AA (2010) The Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase PP2C5 affects seed germination, stomatal aperture, and abscisic acid-inducible gene expression. Plant Physiol 153: 1098–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombet J, Hirt H (2008) Arabidopsis MAPKs: A complex signalling network involved in multiple biological processes. Biochem J 413: 217–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson RJ, Keyse SM (2006) Diverse physiological functions for dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases. J Cell Sci 119: 4607–4615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney T, Friedrich L, Vernooij B, Negrotto D, Nye G, Uknes S, Ward E, Kessmann H, Ryals J (1993) Requirement of salicylic acid for the induction of systemic acquired resistance. Science 261: 754–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González Besteiro MA, Ulm R (2013) Phosphorylation and stabilization of Arabidopsis MAP kinase phosphatase 1 in response to UV-B stress. J Biol Chem 288: 480–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González Besteiro MA, Bartels S, Albert A, Ulm R (2011) Arabidopsis MAP kinase phosphatase 1 and its target MAP kinases 3 and 6 antagonistically determine UV-B stress tolerance, independent of the UVR8 photoreceptor pathway. Plant J 68: 727–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Luan S (2003) Redox control of protein tyrosine phosphatases and mitogen-activated protein kinases in plants. Plant Physiol 132: 1149–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Kajita R, Torii KU, Bergmann DC, Kakimoto T (2007) The secretory peptide gene EPF1 enforces the stomatal one-cell-spacing rule. Genes Dev 21: 1720–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Yokoo T, Kajita R, Onishi T, Yahata S, Peterson KM, Torii KU, Kakimoto T (2009) Epidermal cell density is autoregulated via a secretory peptide, EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR 2 in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 1019–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst RJ, Fujita H, Lee JS, Rychel AL, Garrick JM, Kawaguchi M, Peterson KM, Torii KU (2015) Molecular framework of a regulatory circuit initiating two-dimensional spatial patterning of stomatal lineage. PLoS Genet 11: e1005374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L, Gray JE (2009) The signaling peptide EPF2 controls asymmetric cell divisions during stomatal development. Curr Biol 19: 864–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaoka MM, Pillitteri LJ, Fujii H, Yoshida Y, Bogenschutz NL, Takabayashi J, Zhu JK, Torii KU (2008) SCREAM/ICE1 and SCREAM2 specify three cell-state transitional steps leading to arabidopsis stomatal differentiation. Plant Cell 20: 1775–1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerk D, Bulgrien J, Smith DW, Barsam B, Veretnik S, Gribskov M (2002) The complement of protein phosphatase catalytic subunits encoded in the genome of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 129: 908–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampard GR, Macalister CA, Bergmann DC (2008) Arabidopsis stomatal initiation is controlled by MAPK-mediated regulation of the bHLH SPEECHLESS. Science 322: 1113–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampard GR, Lukowitz W, Ellis BE, Bergmann DC (2009) Novel and expanded roles for MAPK signaling in Arabidopsis stomatal cell fate revealed by cell type-specific manipulations. Plant Cell 21: 3506–3517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Ellis BE (2007) Arabidopsis MAPK phosphatase 2 (MKP2) positively regulates oxidative stress tolerance and inactivates the MPK3 and MPK6 MAPKs. J Biol Chem 282: 25020–25029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Kuroha T, Hnilova M, Khatayevich D, Kanaoka MM, McAbee JM, Sarikaya M, Tamerler C, Torii KU (2012) Direct interaction of ligand-receptor pairs specifying stomatal patterning. Genes Dev 26: 126–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Hnilova M, Maes M, Lin YC, Putarjunan A, Han SK, Avila J, Torii KU (2015) Competitive binding of antagonistic peptides fine-tunes stomatal patterning. Nature 522: 439–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li FC, Wang J, Wu MM, Fan CM, Li X, He JM (2017) Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases affect UV-B-induced stomatal closure via controlling NO in guard cells. Plant Physiol 173: 760–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukowitz W, Roeder A, Parmenter D, Somerville C (2004) A MAPKK kinase gene regulates extra-embryonic cell fate in Arabidopsis. Cell 116: 109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumbreras V, Vilela B, Irar S, Solé M, Capellades M, Valls M, Coca M, Pagès M (2010) MAPK phosphatase MKP2 mediates disease responses in Arabidopsis and functionally interacts with MPK3 and MPK6. Plant J 63: 1017–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAlister CA, Ohashi-Ito K, Bergmann DC (2007) Transcription factor control of asymmetric cell divisions that establish the stomatal lineage. Nature 445: 537–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy JE, Benfey PN (1997) Organization and cell differentiation in lateral roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 124: 33–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAPK Group (2002) Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plants: A new nomenclature. Trends Plant Sci 7: 301–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean MN, Mody A, Broach JR, Ramanathan S (2007) Cross-talk and decision making in MAP kinase pathways. Nat Genet 39: 409–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau JA, Sack FD (2002) Control of stomatal distribution on the Arabidopsis leaf surface. Science 296: 1697–1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi-Ito K, Bergmann DC (2006) Arabidopsis FAMA controls the final proliferation/differentiation switch during stomatal development. Plant Cell 18: 2493–2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillitteri LJ, Sloan DB, Bogenschutz NL, Torii KU (2007) Termination of asymmetric cell division and differentiation of stomata. Nature 445: 501–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Han SK, Dang JH, Garrick JM, Ito M, Hofstetter AK, Torii KU (2017) Autocrine regulation of stomatal differentiation potential by EPF1 and ERECTA-LIKE1 ligand-receptor signaling. eLife 6: e24102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpak ED, McAbee JM, Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU (2005) Stomatal patterning and differentiation by synergistic interactions of receptor kinases. Science 309: 290–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodosiou A, Ashworth A (2002) MAP kinase phosphatases. Genome Biol 3: REVIEWS3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulm R, Revenkova E, di Sansebastiano GP, Bechtold N, Paszkowski J (2001) Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase is required for genotoxic stress relief in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 15: 699–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulm R, Ichimura K, Mizoguchi T, Peck SC, Zhu T, Wang X, Shinozaki K, Paszkowski J (2002) Distinct regulation of salinity and genotoxic stress responses by Arabidopsis MAP kinase phosphatase 1. EMBO J 21: 6483–6493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbrasaite J, Schweighofer A, Kazanaviciute V, Magyar Z, Ayatollahi Z, Unterwurzacher V, Choopayak C, Boniecka J, Murray JA, Bogre L, et al. (2010) MAPK phosphatase AP2C3 induces ectopic proliferation of epidermal cells leading to stomata development in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 5: e15357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Ngwenyama N, Liu Y, Walker JC, Zhang S (2007) Stomatal development and patterning are regulated by environmentally responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildermuth MC, Dewdney J, Wu G, Ausubel FM (2001) Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature 414: 562–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo J, Niu QW, Chua NH (2000) Technical advance: An estrogen receptor-based transactivator XVE mediates highly inducible gene expression in transgenic plants. Plant J 24: 265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]