Abstract

Study Design:

Abstract consensus paper with systematic literature review.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to establish recommendations for treatment of thoracolumbar spine fractures based on systematic review of current literature and consensus of several spine surgery experts.

Methods:

The project was initiated in September 2008 and published in Germany in 2011. It was redone in 2017 based on systematic literature review, including new AOSpine classification. Members of the expert group were recruited from all over Germany working in hospitals of all levels of care. In total, the consensus process included 9 meetings and 20 hours of video conferences.

Results:

As regards existing studies with highest level of evidence, a clear recommendation regarding treatment (operative vs conservative) or regarding type of surgery (posterior vs anterior vs combined anterior-posterior) cannot be given. Treatment has to be indicated individually based on clinical presentation, general condition of the patient, and radiological parameters. The following specific parameters have to be regarded and are proposed as morphological modifiers in addition to AOSpine classification: sagittal and coronal alignment of spine, degree of vertebral body destruction, stenosis of spinal canal, and intervertebral disc lesion. Meanwhile, the recommendations are used as standard algorithm in many German spine clinics and trauma centers.

Conclusion:

Clinical presentation and general condition of the patient are basic requirements for decision making. Additionally, treatment recommendations offer the physician a standardized, reproducible, and in Germany commonly accepted algorithm based on AOSpine classification and 4 morphological modifiers.

Keywords: thoracolumbar spine fracture, traumatic vertebral body fractures, therapy recommendations, morphological modifiers, conservative therapy, operative therapy

Introduction

The treatment strategy for thoracolumbar vertebral fractures is discussed controversially ranging from nonoperative treatment to combined anterior and posterior stabilization.1,2

Therefore, the Spine Section of the German Society for Orthopaedics and Trauma (DGOU) defined basic information for assessment of spinal fractures and recommendations for the treatment of fractures on the thoracolumbar spine based on the experience of surgeons belonging to the working group considering both the literature and their clinical experience. It was published in 2011 in German language.3

The controversies about treatment options have been present in those studies with highest evidence. Whereas Wood et al1,4 found no advantages between operative stabilization compared with nonoperative treatment in patient with thoracolumbar burst fractures, Siebenga et al2 reported significantly higher radiologic kyphosis and significantly higher pain scores after nonoperative treatment. So only following the literature for many aspects there are no conclusive recommendations available for the treatment of fractures of thoracolumbar spine.

Recently, Scholz et al5 reported less loss of reduction after combined anterior and posterior stabilization.

Thus, the aim of this review is to offer the surgeon the best available objective criteria to choose an appropriate treatment strategy by integrating the current literature until 2017 and by analyzing fracture stability based on the new AOSpine classification,6 including newly introduced morphological modifiers enabling the surgeon to describe the fracture pattern more specific.

Methods

The recommendations refer to acute traumatic vertebral fractures of the thoracolumbar spine excluding pathologic fractures, such as malignancies and osteoporosis. In case of a multiple injured patient, diagnosis and therapy has to be adapted.

The project was initiated in September 2008 and published in Germany in 2011. The 19 members of the expert group were recruited from all over Germany working in hospitals of all levels of care. In total, there were 9 meetings and 20 hours of video conferences in the consensus process. For further evaluation and input, the recommendations were sent several times via emails to all members of the Spine Section.

These recommendations were redone in 2017 based on current literature, including the new AOSpine classification. A systematic review was performed by UJS, AH, and APV on the January 13, 2018. Thereby, Medline was reviewed by “vertebral body fracture” AND “thoracolumbar spine” between January 2011 and December 2017. All studies dealing with pathologic/osteoporotic fractures, nonacute fracture situations, children or adolescent patients, experimental studies, reviews, cervical, and sacral fractures were excluded. Additionally, only studies in English and German language were evaluated. A methodological assessment of the included studies was not performed, but we included only minimum level-3 evidence studies. Afterward another 7 meetings and 12 hours of video conferences were held. Therefore, the recommendations are based on an expert opinion with a systematic review of the current literature.

Results

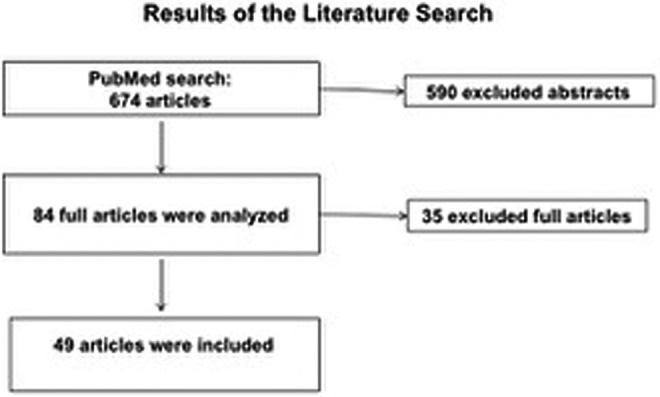

A total of 674 studies were identified by the systematic search using the defined criteria. All these abstracts were analyzed to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Only clinical studies with level-3 evidence or higher evaluating treatment recommendations for thoracolumbar spine fractures were included. Thus, a total of 590 publications were excluded based on the abstracts. Another 35 publications were excluded based on the full articles.

Finally, 49 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The main messages of all included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the literature research.

Table 1.

Summary of the Main Messages of All Included Studies.

| Topic | Main Message | Studies (Level of Evidence) |

|---|---|---|

| Parameters associated with reduction loss |

|

Shen et al7 (2) De Iure et al8 (3) Jang et al9 (3) Curfs et al10 (3) Elzinga et al11 (3) Inaba et al12 (3) |

| Posterior ligament complex injury |

|

Hiyama et al13 (2) Tang et al14 (3) Radcliff et al15 (3) Schroeder et al16 (3) |

| Minimal invasive posterior stabilization compared to an open approach |

|

Vanek et al17 (2) Wang et al18 (3) Ntilikina et al19 (3) Loibl et al20 (3) Li et al21 (3) Lee et al22 (3) |

| Intermediate screws at the fracture level |

|

Ye et al23 (3) Lin et al24 (3) Formica et al25 (3) Zhao et al26 (3) Kose et al27 (3) |

| Short segmental stabilization |

|

Dobran et al28 (2) Ugras et al29 (2) Özbek et al30 (3) La Maida et al31 (3) Park et al32 (3) Cankaya et al33 (3) Liu et al34 (3) Khare et al35 (3) Spiegl et al36 (3) |

| Vertebral body augmentation |

|

Korovessis et al37 (3) Chen et al38 (3) Verlaan et al39 (3) Klezl et al40 (3) |

| Surgical decompression |

|

Bourassa-Moreau et al41 (3) Cui et al42 (3) |

| Implant removal |

|

Chou et al43 (3) Spiegl et al44 (3) |

| Fusion |

|

Chou et al45 (2) Baumann et al46 (3) Antoni et al47 (3) Kang et al48 (3) |

| Nonoperative vs operative treatment |

|

Wood et al4 (1) |

| Anterior vs posterior stabilization |

|

Scholz et al5 (1) Lin et al49 (2) Zheng et al50 (3) Schmid et al51 (3) Spiegl et al52 (3) Machino et al53 (3) |

Abbreviations: Th, thorcic vertebral body; L, lumbar vertebral body; TLICS, thoracolumbar injury classification and severity score; proc., processus; PLC, posterior ligament complex; LSS, load share classification; IR, implant removal.

Classification

The classification of these fractures is based on the new AOSpine Thoracolumbar Classification System.6 Injuries can be divided into 3 groups:

Compression injuries

Distraction injuries

Translation injuries

The neurological status of the patient is graded according to the modifiers of the new AOSpine classification as follows:

N0 Neurologically intact

N1 Transient neurologic deficit, which is no longer present

N2 Radicular symptoms

N3 Incomplete spinal cord injury or any degree of cauda equina injury

N4 Complete spinal cord injury

NX Neurologic status is unknown due to sedation or head injury

Morphological Criteria

The precise assessment and classification of spinal fractures is of great importance, particularly with regard of treatment decision making.54 To facilitate this in addition to the AOSpine Thoracolumbar Classification System 4 morphological criteria are derivable from routine X-ray and computed tomography (CT) images. These may work as morphological modifiers (MM) for treatment algorithms:

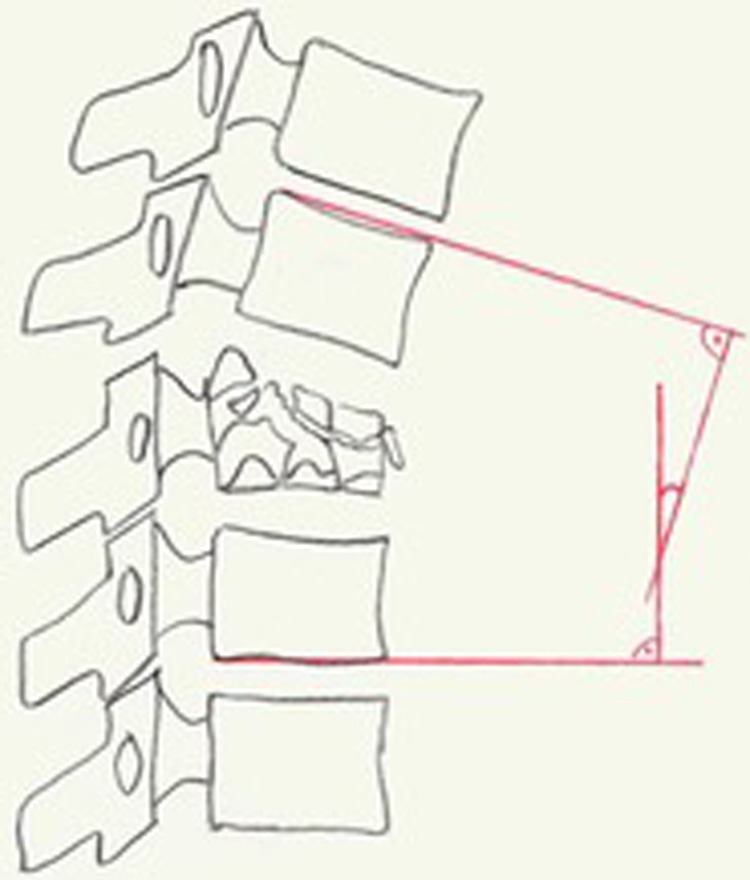

MM 1: Disorder in the Physiological Alignment of the Vertebral Column

Fractures can disturb the physiological alignment of the spinal column both in the coronal and sagittal plane. For the description of deviation in the sagittal plane, the monosegmental and the bisegmental endplate angle (EPA) are used analog to the Cobb’s angle.55,56

The monosegmental EPA is measured by drawing lines parallel to the upper endplate of the vertebral body adjacent to the fractured and the lower endplate of the fractured vertebral body.57,58 The angle between these lines is the EPA (illustrated in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Morphological modifier 1 (MM 1): Disorder in the physiological alignment of the vertebral column: monosegmental endplate angle (EPA).

The monosegmental EPA cannot be defined for complete burst fractures; in these cases, the bisegmental EPA has to be used. The bisegmental EPA is measured by drawing lines parallel to the upper endplate of the vertebral body adjacent cranial to the fractured and the lower endplate of the adjunct caudal vertebral body. The angle between these lines is the bisegmental EPA (illustrated in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Morphological modifier 1 (MM 1): Disorder in the physiological alignment of the vertebral column: bisegmental endplate angle (EPA).

Similarly, the scoliosis angle can additionally be used for coronal plane deformities. This can be done both mono- and bisegmentally (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Morphological modifier 1 (MM 1): Disorder in the physiological alignment of the vertebral column: scoliosis angle.

Whenever possible, EPA should be measured on posterior-anterior standing radiographs.59 Excluded to standing are patients with suspicion of highly unstable fractures.

For the selection of treatment, more important than the measured EPA is the calculated δEPA. This angle describes the traumatic deviation from the individual sagittal profile of the spine (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Individual sagittal profile: The posttraumatic bisegmental kyphotic angle of 20° (a) in a physiologically 5° to 10° lordotic area at L 1 (δEPA of 30°) is more clinical relevance than 20° kyphosis (b) in a physiologically 10° kyphotic area at T 8 (δEPA 10°).

When the calculated δEPA is less than 15° to 20° no further deviation of the spinal alignment to a degree demanding surgical correction is expected.60 Therefore, conservative functional therapy is indicated in these cases. However, further clinical and radiological follow-ups are necessary to rule out relevant deviation of the alignment. In cases δEPA is greater than 15° to 20°, an injury to the posterior ligament complex is very common and operative treatment has to be considered.57

Patients with a scoliotic angle of less than 10° can be treated conservatively, in case of more than 10° operative therapy has to be discussed.

MM 2: Comminution of the Vertebral Body

The extent of vertebral body destruction has a high impact on treatment strategy, especially with regard to the need for anterior column reconstruction.8,61

The degree of destruction can be classified according to the McCormack Load Sharing Classification. The vertebral body is divided equally into cranial, middle, and caudal horizontal thirds61 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Morphological Modifier II (MM II): Comminution of the vertebral body.

The fragments may be displaced or nondisplaced. The more the displacement occurs the higher is the degree of instability and the loss of correction. Fragment displacement at the upper or lower endplate is usually associated with adjacent intervertebral disc lesion.

MM 3: Stenosis of the Spinal Canal

Spinal canal stenosis is defined as the estimated percentage loss of spinal canal area at the level of the most narrowed spinal canal on axial CT compared with the physiological size at the adjacent levels (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Morphological Modifier III (MM III): Stenosis of the spinal canal.

MM 4: Intervertebral Disc Lesion

Traumatic intervertebral disc lesions do not show sufficient spontaneous healing capacity in adults.62 Disc lesions can be expected in patients with serious endplate defects. Considering the expected deterioration of the individual sagittal alignment, anterior spondylodesis has to be discussed. In cases of unclear degree of disc lesion further evaluation by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful.63,64

Diagnosis

A detailed history and physical examination including a thorough objective neurological examination are essential first steps to detect vertebral fractures. Ideally, this should be performed at the scene of the accident, before analgesia is administered.

A thorough history should include the precise magnitude and direction of the injuring force (height of fall, surface of impact, compressive, distractive and rotatory forces, etc).

Clinical examination should include a thorough head-to-toe examination. Assessment of soft tissue injury, local swelling, tenderness, palpable steps or deviations of the physiological alignment at the spine is mandatory.

An initial neurologic examination of the motor function and sensation of the upper and lower extremities are essential to determine the level of neurologic deficits on clinical basis.

A detailed reevaluation of the nervous system has to be carried out after arrival at the hospital. Assessment of motor function deficits, disturbance of bladder and bowel sphincter function, and the sensation particularly at the perianal region has to be performed. These findings have to be periodically recorded throughout the course of treatment.

High-dose glucocorticoid administration (National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study–NASCIS II) is not recommended as a standard for the treatment in patients with polytrauma, moderate to severe chest trauma, history of gastrointestinal disease, and when patient is older than 60 years.65 It can be used in young patients with acute traumatic paraplegia without contraindications. Adverse effects such as respiratory and gastrointestinal complications can outweigh beneficial effects after admission of high-dose cortisone.

Radiology

Generally, conventional radiographs of the vertebral spine in 2 planes are required in suspicion of vertebral body fractures. A CT scan is indicated if instability and/or spinal canal stenosis cannot be ruled out or if the region of interest may not be adequately visualized.66 Conventional radiography can be excluded in patients who received a CT examination of the region of interest initially (whole-body multislice CT in severe multiple trauma patients). The X-ray beam should be focused on the injured vertebra. A minimum of 2 vertebral bodies adjacent to the affected one should be included. Similarly, the CT scan should include at least one vertebral body cranially and caudally adjacent to the injured one.

An MRI is indicated in acute trauma cases when the neurological symptoms do not correspond to the pictures shown by other imaging modalities. Additionally, MRI is a useful tool to detect lesions of intervertebral discs and/or to rule out a posterior ligament injury.66-69

Supervised erected control radiographs are mandatory after patient mobilization. Other investigations like discography, myelography, myelo-CT, functional CT, functional MRI, angiography, and angio-CT are generally not indicated. Those diagnostic tools might be used in selected patients based on an individual decision making by the treating surgeon.

Principles of Treatment of Spinal Fractures

The basic principles of the treatment of vertebral fractures are presented here. However, the treatment of spinal fractures has to be individualized for all age, bone quality, activity level, perioperative risk factors, accompanied injuries, compliance, and individual demands.

Surgery should be performed as soon as possible in case of:

Open spinal injuries. These may be caused by external forces (gunshot, incisions) and/or major dislocations.

Neurological deficits with relevant narrowing of the spinal canal.70 A spinal shock can mask the true neurological status during the first 48 hours after injury. The same applies to a patient with unknown neurological status, for example, sedated patient with relevant traumatic spinal canal stenosis.

Highly unstable fractures (type C).

In multiple injured patients with highly unstable spine injuries on the basis of damage control surgery.71

Patients with vertebral body fractures and preexisting preponderance to instability such as in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Conservative Therapy

The goal of conservative therapy is an early mobilization of the patient.72 Initially, a short period of bed rest might be necessary. Sufficient pain therapy is essential. Successful conservative therapy is dependent on close collaboration of patient, physiotherapist, nursing staff and attending physician. Regular clinical and radiological follow-up examinations are necessary to monitor treatment. Erect radiographs are required after mobilization. In case of doubt, CT or MRI examination might be necessary. A switch of the treatment strategy to an operative procedure has to be considered at any time if the clinical and/or radiological findings deteriorate significantly.

Generally, sufficient patient mobilization can be expected at the latest 1 week after trauma in patients with mono-traumatic injury and sufficient analgesic medication.

Bracing therapy is no longer recommended for the treatment of vertebral fractures. Independent randomized control trials reported no benefit from wearing braces as a part of a conservative treatment.73,74 No improvement of any radiologic parameters was seen. In contrast, inferior clinical results were recorded after the use of plaster of Paris casts compared with brace therapy.75

Operative Treatment

The aim of an operative treatment is an anatomical reconstruction of the vertebral spine with immediate stability and relief of any spinal cord compression. Clinical and radiological outcome should be equal or superior to conservative therapy. It is important to ensure that optimal technical and personal conditions are available during the procedure.

To speak with the same language, correct terminology of operative techniques for spinal fractures is essential. This includes the terms “instrumentation,” “spinal fusion,” and “anterior reconstruction.” Instrumentation is defined as posterior or anterior stabilization without the definitive fusion of articulation motion segments. Spinal fusion or “spondylodesis” is defined as a permanent fusion of a motion segment. This can be done either through an anterior or a posterior approach. The technique of posterior fusion includes decortication of the interbody joint, placement of autogenous or allogenic bone graft or use of osteoconductive and/or osteoinductive bone substitutes. Anterior reconstruction is defined by an anatomical restoration of the ventral column with the use of implants (cages, ventral instrumentation), grafts, or other materials. This can also be performed through a posterior approach.

There are no clear recommendations regarding the best time to carry out an operative procedure. Patients with neurologic deficits caused by traumatic spinal canal stenosis should be treated as an emergency.

For the assessment of traumatic spinal canal stenosis, the location of stenosis, the neurological status and the amount of subdural reserve space must be taken into consideration.65 Surgical decompression can be done either directly (eg, laminectomy) or indirectly by reducing the vertebral fracture.57,76

In cases of clinically relevant spinal canal stenosis after an attempt of closed reduction, emergency surgical decompression is indicated.41 An attempt of closed reduction can be done when no early surgical decompression can be performed.

Severe traumatic spinal canal stenosis without any neurologic deficit does not necessarily indicate direct decompression.

While selecting the appropriate strategy for reduction and stabilization of the vertebral body fracture, it is important to consider the degree of damage to the intervertebral disc.61

An uninjured motion segment, which is bridged by posterior stabilization, should be relieved as soon as possible after the consolidation of the fracture by an early removal or shortening of the posterior instrumentation. This can be done after 6 to 12 months postoperatively.43

Long segmental instrumentation should be used at the upper and middle thoracic spine (above T 10). At the thoracolumbar junction and the lumbar spine short segmental stabilization is mostly sufficient with better clinical outcomes.28-30,32,33,35 Thereby, the implementation of intermediate screws at the fracture level has shown to increase construct stability and to minimize reduction loss.23-27 Monoaxial implants should be used if no additional anterior stabilization is performed.36,77,78 In contrast, loss of reduction is more likely in patients instrumented with polyaxial screws. Monosegmental bridging can be considered in fractures affecting a single motion segment.31,34 Transverse connecting rods as well as implantation of index screws can be used to increase stability.78 Posterior and anterior approaches can be done open or minimally invasive. The main goal of posterior stabilization has to be an anatomic reduction. If this can be achieved by a minimal invasive approach this should be preferred.17-22 Patients will benefit from a minimal invasive anterior approach by reducing morbidity and improve mobilization.64 Cement augmentation with PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate) cement is a useful tool in patients with reduced bone quality. It is not recommended in young patients with a healthy bone stock.

In addition to optimally performed surgery, appropriate physiotherapy and sufficient pain therapy are essential in order to gain good outcomes after vertebral fractures. Therefore, a good cooperation between the patients, surgeons, nursing staff, and physiotherapists is necessary to achieve this.

Recommended Procedures for Spinal Fractures According to the AOSpine Thoracolumbar Classification System

Treatment has to be indicated individually based on the clinical presentation, the general condition of the patient, and radiological parameters.

The morphological modifiers (MM), which may be of importance are added to each type of fracture.

A0: Minor, Nonstructural Fracture

Treatment of choice is early mobilization, adequate analgesia, and physiotherapy.

A1: Wedge-Compression—MM 1

δEPA < 5° to 20° conservative therapy.

δEPA >15° to 20° operative treatment, at least monosegmental instrumentation.

A2: Split—MM 2 and MM 4

Treatment of choice is early mobilization, adequate analgesia, and physiotherapy.

Wide fragment separation and/or relevant lesion of the intervertebral disc can be an indication for surgery. An anterior bisegmental reconstruction with or without posterior instrumentation has to be considered.61

A3: Incomplete Burst—MM 1, MM 2, MM 3, and MM 4

δEPA <15° to 20° and/or scoliosis <10° conservative therapy.

δEPA >15° to 20° and/or scoliosis >10° operative treatment.

At least monosegmental posterior instrumentation has to be considered. A monosegmental posterior fusion is possible. Anterior reconstruction should be performed depending on δEPA and destruction of the vertebral body. For vertebral body destruction <1/3 anterior reconstruction is optional, for destruction 1/3 to 2/3 monosegmental reconstruction is recommended.61 Wide separation of the fragments and critical narrowing of the spinal canal is a further indication for surgical treatment. A standalone anterior or posterior reconstruction is possible in selected cases.

A4: Complete Burst—MM 1, MM 2, MM 3, and MM 4

δEPA <15° to 20° and/or scoliosis <10° conservative therapy.

δEPA > 15° to 20° and/or scoliosis >10° operative treatment.

Because of the morphology of these fractures, it is possible that there is gross fragment displacement with critical narrowing of the spinal canal without considerable deviation of δEPA and scoliosis angle.57 Wide separation of the fragments and critical narrowing of the spinal canal is a further indication for surgical treatment.

At least bisegmental posterior instrumentation has to be considered. Because of the complete destruction of the vertebral bodies, a bisegmental anterior reconstruction should be carried out in displaced fractures. A standalone ventral or posterior reconstruction is possible in selected cases.

B1: Transosseous Tension Band Disruption—Chance Fracture

An operative approach including fracture reduction and bisegmental posterior instrumentation is indicated.79

B2: Posterior Tension Band Disruption—MM 1, MM 2, MM 3, and MM 4

At least posterior instrumentation should be performed. Additional anterior reconstruction may be indicated depending on the severity of the corresponding ventral column defect.57

B3: Hyperextension—MM 1, MM 2, MM 3, and MM 4

Fracture reduction and posterior instrumentation is recommended. This can be done monosegmentally in many cases. Additional monosegmental anterior reconstruction might be necessary depending on the severity of the anterior column defect.

However, this fracture type is commonly seen in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. In these cases, long segmental posterior instrumentation has to be performed.80

C: Displacement/Dislocation—MM 1, MM 2, MM 3, and MM 4

Fracture reduction and posterior instrumentation is indicated. Short segmental instrumentation is commonly sufficient in monosegmental injuries. Extended injuries should be addressed with longer posterior constructs. A cross-connector should be used in severe rotational instable fractures and short segmental procedures.64 In case of posterior tension band disruption a posterior spondylodesis has to be considered. Combination of monosegmental spondylodesis and long segmental posterior instrumentation is possible. In these patients, implant removal of uninjured bridged motion segments is recommendable after 6 to 12 months postoperatively.44 Additional anterior reconstruction is indicated depending on the corresponding ventral column defect.

Discussion

By reviewing the literature, there are 6 randomized control studies focusing on the treatment of thoracolumbar fractures. Controversies regarding the superiority of conservative versus operative therapy were reported in studies comparing conservative versus operative strategies. Whereas Wood et al4 found similar local kyphosis, pain levels, and return to work rates without significant differences after a follow-up of 16 years, Siebenga et al2 found significant higher kyphotic malposition (19° vs 8°), significant higher pain scores, and higher functional disability scores (Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire–24) in the nonoperative group. No difference in the number of complications was reported.

Similarly, controversies regarding the advantages and disadvantages of different surgical techniques exist. Wood et al81 compared anterior versus posterior fusion in patients with thoracolumbal burst fractures. The authors found a higher complication rate after posterior fusion with similar clinical and radiological outcome after the final follow-up. In contrast, Korovessis et al82 and the RASPUTHINE pilot study5 reported significant higher reduction loss after posterior-only stabilization compared to a dorsoventral approach without significant differences of clinical outcome. Wang et al83 compared the outcome after posterior short segmental stabilization with or without fusion and found higher complication rates additional segmental fusion without any clinical and radiological differences.

In conclusion of the existing studies with the highest level of evidence, a clear recommendation regarding the treatment (operative vs conservative) or regarding the type of surgery (posterior vs anterior vs combined anterior-posterior) cannot be given.

However, the authors are aware that their proposal is based mainly on clinical experience with a low level of evidence. Hence the therapeutic recommendations in this article have proven to be helpful for daily practice in several German spine and trauma centers.

The morphological modifiers might be considered in further research projects to evaluate their impact on daily decision making and outcome. In the future, more differentiated evidence-based therapy algorithms will be hopefully available.

Conclusion

Correct terminology of spinal parameters and therapeutic algorithms are essential for professional communication and treatment recommendations.

Correct assessment of the fracture morphology is depending on accurate diagnosis based on new AOSpine Thoracolumbar Classification System and morphological modifiers. This is the basic prerequisite and mandatory to understand the degree of instability.

The important morphological modifiers for decision making are disturbance of the sagittal or coronal alignment, degree of vertebral body destruction, stenosis of the spinal canal, and intervertebral disc lesion.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The treatment recommendations were established in a joint expert group of the Spine Section of the German Society for Orthopaedics and Trauma. The English article was written by Akhil P. Verheyden, Alexander Hölzl, Ulrich J. Spiegl. Coauthors in alphabetical order: Helmut Ekkerlein, Erol Gercek, Stefan Hauck, Christoph Josten, Frank Kandziora, Sebastian Katscher, Christian Knop, Philipp Kobbe, Wolfgang Lehmann, Rainer Meffert, Christian W. Müller, Axel Partenheimer, Christian Schinkel, Philip Schleicher, Klaus J. Schnake, Matti Scholz, and Christoph Ulrich.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Wood K, Buttermann G, Mehbod A, Garvey T, Jhanjee R, Sechriest V. Operative compared with nonoperative treatment of a thoracolumbar burst fracture without neurological deficit. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siebenga J, Leferink VJ, Segers MJ, et al. Treatment of traumatic thoracolumbar spine fractures: a multicenter prospective randomized study of operative versus nonsurgical treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2881–2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verheyden AP, Hölzl A, Ekkerlein H, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of thoracolumbar and lumbar spine injuries [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2011;114:9–16. doi:10.1007/s00113-010-1934-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wood KB, Buttermann GR, Phukan R, et al. Operative compared with nonoperative treatment of a thoracolumbar burst fracture without neurological deficit: a prospective randomized study with follow-up at sixteen to twenty-two years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:3–9. doi:10.2106/JBJS.N.00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scholz M, Kandziora F, Tschauder T, Kremer M, Pingel A. Prospective randomized controlled comparison of posterior vs. posterior-anterior stabilization of thoracolumbar incomplete cranial burst fractures in neurological intact patients: the RASPUTHINE pilot study [published online October 25, 2017]. Eur Spine J. doi:10.1007/s00586-017-5356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vaccaro AR, Oner C, Kepler CK, et al. AOSpine thoracolumbar spine injury classification system: fracture description, neurological status, and key modifiers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38:2028–2037. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a8a381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shen J, Xu L, Zhang B, Hu Z. Risk factors for the failure of spinal burst fractures treated conservatively according to the Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity Score (TLICS): a retrospective cohort trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135735 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Iure F, Lofrese G, De Bonis P, et al. Vertebral body spread in thoracolumbar burst fractures can predict posterior construct failure. Spine J. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2017.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jang HD, Bang C, Lee JC, et al. Risk factor analysis for predicting vertebral body re-collapse after posterior instrumented fusion in thoracolumbar burst fracture. Spine J. 2018;18:285–293. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2017.07.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Curfs I, Grimm B, van der Linde M, Willems P, van Hemert W. Radiological prediction of posttraumatic kyphosis after thoracolumbar fracture. Open Orthop J. 2016;10:135–142. doi:10.2174/1874325001610010135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elzinga M, Segers M, Siebenga J, Heilbron E, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Bakker F. Inter- and intraobserver agreement on the load sharing classification of thoracolumbar spine fractures. Injury. 2012;43:416–422. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Inaba K, DuBose JJ, Barmparas G, et al. Clinical examination is insufficient to rule out thoracolumbar spine injuries. J Trauma. 2011;70:174–179. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d3cc6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hiyama A, Watanabe M, Katoh H, Sato M, Nagai T, Mochida J. Relationships between posterior ligamentous complex injury and radiographic parameters in patients with thoracolumbar burst fractures. Injury. 2015;46:392–398. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2014.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tang P, Long A, Shi T, Zhang L, Zhang L. Analysis of the independent risk factors of neurologic deficit after thoracolumbar burst fracture. J Orthop Surg Res. 2016;11:128 doi:10.1186/s13018-016-0448-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Radcliff K, Kepler CK, Rubin TA, et al. Does the load-sharing classification predict ligamentous injury, neurological injury, and the need for surgery in patients with thoracolumbar burst fractures? Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16:534–538. doi:10.3171/2012.3.SPINE11570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schroeder GD, Kepler CK, Koerner JD, et al. A worldwide analysis of the reliability and perceived importance of an injury to the posterior ligamentous complex in AO type A fractures. Global Spine J. 2015;5:378–382. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1549034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vanek P, Bradac O, Konopkova R, de Lacy P, Lacman J, Benes V. Treatment of thoracolumbar trauma by short-segment percutaneous transpedicular screw instrumentation: prospective comparative study with a minimum 2-year follow-up. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20:150–156. doi:10.3171/2013.11.SPINE13479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang B, Fan Y, Dong J, et al. A retrospective study comparing percutaneous and open pedicle screw fixation for thoracolumbar fractures with spinal injuries. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8104 doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000008104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ntilikina Y, Bahlau D, Garnon J, et al. Open versus percutaneous instrumentation in thoracolumbar fractures: magnetic resonance imaging comparison of paravertebral muscles after implant removal. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;27:235–241. doi:10.3171/2017.1.SPINE16886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loibl M, Korsun M, Reiss J, et al. Spinal fracture reduction with a minimal-invasive transpedicular Schanz Screw system: clinical and radiological one-year follow-up. Injury. 2015;46(suppl 4):S75–S82. doi:10.1016/S0020-1383(15)30022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li KC, Yu SW, Li A, et al. Subpedicle decompression and vertebral reconstruction for thoracolumbar Magerl incomplete burst fractures via a minimally invasive method. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39:433–442. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee JK, Jang JW, Kim TW, Kim TS, Kim SH, Moon SJ. Percutaneous short-segment pedicle screw placement without fusion in the treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures: is it effective? Comparative study with open short-segment pedicle screw fixation with posterolateral fusion. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013;155:2305–2312. doi:10.1007/s00701-013-1859-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ye C, Luo Z, Yu X, Liu H, Zhang B, Dai M. Comparing the efficacy of short-segment pedicle screw instrumentation with and without intermediate screws for treating unstable thoracolumbar fractures. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7893 doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000007893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin YC, Fan KF, Liao JC. Two additional augmenting screws with posterior short-segment instrumentation without fusion for unstable thoracolumbar burst fracture—comparisons with transpedicular grafting techniques. Biomed J. 2016;39:407–413. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Formica M, Cavagnaro L, Basso M, et al. Which patients risk segmental kyphosis after short segment thoracolumbar fracture fixation with intermediate screws? Injury. 2016;47(suppl 4):S29–S34. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2016.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao QM, Gu XF, Yang HL, Liu ZT. Surgical outcome of posterior fixation, including fractured vertebra, for thoracolumbar fractures. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2015;20:362–367. doi:10.17712/nsj.2015.4.20150318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kose KC, Inanmaz ME, Isik C, Basar H, Caliskan I, Bal E. Short segment pedicle screw instrumentation with an index level screw and cantilevered hyperlordotic reduction in the treatment of type-A fractures of the thoracolumbar spine. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:541–547. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.96B4.33249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dobran M, Nasi D, Brunozzi D, et al. Treatment of unstable thoracolumbar junction fractures: short-segment pedicle fixation with inclusion of the fracture level versus long-segment instrumentation. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2016;158:1883–1889. doi:10.1007/s00701-016-2907-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ugras AA, Akyildiz MF, Yilmaz M, Sungur I, Cetinus E. Is it possible to save one lumbar segment in the treatment of thoracolumbar fractures? Acta Orthop Belg. 2012;78:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ozbek Z, Ozkara E, Onner H, et al. Treatment of unstable thoracolumbar fractures: does fracture-level fixation accelerate the bone healing? World Neurosurg. 2017;107:362–370. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. La Maida GA, Luceri F, Ferraro M, Ruosi C, Mineo GV, Misaggi B. Monosegmental vs bisegmental pedicle fixation for the treatment of thoracolumbar spine fractures. Injury. 2016;47(suppl 4):S35–S43. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2016.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park SR, Na HY, Kim JM, Eun DC, Son EY. More than 5-year follow-up results of two-level and three-level posterior fixations of thoracolumbar burst fractures with load-sharing scores of seven and eight points. Clin Orthop Surg. 2016;8:71–77. doi:10.4055/cios.2016.8.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cankaya D, Balci M, Deveci A, Yoldas B, Tuncel A, Tabak Y. Better life quality and sexual function in men and their female partners with short-segment posterior fixation in the treatment of thoracolumbar junction burst fractures. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:1128–1134. doi:10.1007/s00586-015-4145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu L, Gan Y, Zhou Q, et al. Improved monosegment pedicle instrumentation for treatment of thoracolumbar incomplete burst fractures. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:357206 doi:10.1155/2015/357206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khare S, Sharma V. Surgical outcome of posterior short segment trans-pedicle screw fixation for thoracolumbar fractures. J Orthop. 2013;10:162–167. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spiegl UJ, Jarvers JS, Heyde CE, Glasmacher S, Von der Höh N, Josten C. Delayed indications for additive ventral treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures: what correction loss is to be expected [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2015;119:664–672. doi:10.1007/s00113-015-0056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Korovessis P, Mpountogianni E, Syrimpeis V. Percutaneous pedicle screw fixation plus kyphoplasty for thoracolumbar fractures A2, A3 and B2. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:1492–1498. doi:10.1007/s00586-016-4743-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen C, Lv G, Xu B, Zhang X, Ma X. Posterior short-segment instrumentation and limited segmental decompression supplemented with vertebroplasty with calcium sulphate and intermediate screws for thoracolumbar burst fractures. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:1548–1557. doi:10.1007/s00586-014-3374-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Verlaan JJ, Somers I, Dhert WJ, Oner FC. Clinical and radiological results 6 years after treatment of traumatic thoracolumbar burst fractures with pedicle screw instrumentation and balloon assisted endplate reduction. Spine J. 2015;15:1172–1178. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klezl Z, Majeed H, Bommireddy R, John J. Early results after vertebral body stenting for fractures of the anterior column of the thoracolumbar spine. Injury. 2011;42:1038–1042. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bourassa-Moreau E, Mac-Thiong JM, Li A, et al. Do patients with complete spinal cord injury benefit from early surgical decompression? Analysis of neurological improvement in a prospective cohort study. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:301–306. doi:10.1089/neu.2015.3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cui H, Guo J, Yang L, Guo Y, Guo M. Comparison of therapeutic effects of anterior decompression and posterior decompression on thoracolumbar spine fracture complicated with spinal nerve injury. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31:346–350. doi:10.12669/pjms.312.6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chou PH, Ma HL, Liu CL, et al. Is removal of the implants needed after fixation of burst fractures of the thoracolumbar and lumbar spine without fusion? a retrospective evaluation of radiological and functional outcomes. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B:109–116. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.98B1.35832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Spiegl UJ, Jarvers JS, Glasmacher S, Heyde CE, Josten C. Release of moveable segments after dorsal stabilization: impact on affected discs [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2016;119:747–754. doi:10.1007/s00113-014-2675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chou PH, Ma HL, Wang ST, Liu CL, Chang MC, Yu WK. Fusion may not be a necessary procedure for surgically treated burst fractures of the thoracolumbar and lumbar spines: a follow-up of at least ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:1724–1731. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.01486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Baumann F, Krutsch W, Pfeifer C, Neumann C, Nerlich M, Loibl M. Posterolateral fusion in acute traumatic thoracolumbar fractures: a comparison of demineralized bone matrix and autologous bone graft. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2015;82:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Antoni M, Charles YP, Walter A, Schuller S, Steib JP. Fusion rates of different anterior grafts in thoracolumbar fractures. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28:E528–E533. doi:10.1097/BSD.0b013e3182aab2bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kang CN, Cho JL, Suh SP, Choi YH, Kang JS, Kim YS. Anterior operation for unstable thoracolumbar and lumbar burst fractures: tricortical autogenous iliac bone versus titanium mesh cage. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2013;26:E265–E271. doi:10.1097/BSD.0b013e3182867489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin B, Chen ZW, Guo ZM, Liu H, Yi ZK. Anterior approach versus posterior approach with subtotal corpectomy, decompression, and reconstruction of spine in the treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures: a prospective randomized controlled study [published online June 1, 2011]. J Spinal Disord Tech. doi:10.1097/BSD.0b013e3182204c53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zheng GQ, Wang Y, Tang PF, et al. Early posterior spinal canal decompression and circumferential reconstruction of rotationally unstable thoracolumbar burst fractures with neurological deficit. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:2343–2347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schmid R, Lindtner RA, Lill M, Blauth M, Krappinger D, Kammerlander C. Combined posteroanterior fusion versus transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) in thoracolumbar burst fractures. Injury. 2012;43:475–479. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Spiegl U, Hauck S, Merkel P, Bühren V, Gonschorek O. Six-year outcome of thoracoscopic ventral spondylodesis after unstable incomplete cranial burst fractures of the thoracolumbar junction: ventral versus dorso-ventral strategy. Int Orthop. 2013;37:1113–1120. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-1879-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Machino M, Yukawa Y, Ito K, Nakashima H, Kato F. Posterior/anterior combined surgery for thoracolumbar burst fractures—posterior instrumentation with pedicle screws and laminar hooks, anterior decompression and strut grafting. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:573–579. doi:10.1038/sc.2010.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Denis F. The three column spine and its significance in the classification of acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8:817–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kuklo TR, Polly DW, Owens BD, Zeidman SM, Chang AS, Klemme WR. Measurement of thoracic and lumbar fracture kyphosis: evaluation of intraobserver, interobserver, and technique variability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cobb JR. Outline for the study of scoliosis. Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1948;5:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Reinhold M, Knop C, Beisse R, et al. Operative treatment of 733 patients with acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries: comprehensive results from the second, prospective, Internet-based multicenter study of the Spine Study Group of the German Association of Trauma Surgery. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1657–1676. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Knop C, Blauth M, Buhren V, et al. Surgical treatment of injuries of the thoracolumbar transition—3: follow-up examination. Results of a prospective multi-center study by the “Spinal” Study Group of the German Society of Trauma Surgery [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2001;104:583–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mehta JS, Reed MR, McVie JL, Sanderson PL. Weight-bearing radiographs in thoracolumbar fractures: do they influence management? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Katscher S, Verheyden P, Gonschorek O, Glasmacher S, Josten C. Thoracolumbar spine fractures after conservative and surgical treatment. Dependence of correction loss on fracture level [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:20–27. doi:10.1007/s00113-002-0459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. McCormack T, Karaikovic E, Gaines RW. The load sharing classification of spine fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:1741–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sander AL, Lehnert T, El Saman A, Eichler K, Marzi I, Laurer H. Outcome of traumatic intervertebral disk lesions after stabilization by internal fixator. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:140–145. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.11590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sander AL, Laurer H, Lehnert T, et al. A clinically useful classification of traumatic intervertebral disk lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:618–623. doi:10.2214/AJR.12.8748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Spiegl UJ, Josten C, Devitt BM, Heyde CE. Incomplete burst fractures of the thoracolumbar spine: a review of literature. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:3187–3198. doi:10.1007/s00586-017-5126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1405–1411. doi:10.1056/NEJM199005173222001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dai LY, Jin WJ. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability in the load sharing classification of the assessment of thoracolumbar burst fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Oner FC, vd Rijt RH, Ramos LM, Groen GJ, Dhert WJ, Verbout AJ. Correlation of MR images of disc injuries with anatomic sections in experimental thoracolumbar spine fractures. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:194–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pizones J, Izquierdo E, Alvarez P, et al. Impact of magnetic resonance imaging on decision making for thoracolumbar traumatic fracture diagnosis and treatment. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(suppl 3):390–396. doi:10.1007/s00586-011-1913-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schnake KJ, von Scotti F, Haas NP, Kandziora F. Type B injuries of the thoracolumbar spine: misinterpretations of the integrity of the posterior ligament complex using radiologic diagnostics [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2008;111:977–984. doi:10.1007/s00113-008-1503-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fehlings MG, Perrin RG. The timing of surgical intervention in the treatment of spinal cord injury: a systematic review of recent clinical evidence. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(11 suppl):S28–S35. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000217973.11402.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schinkel C, Anastasiadis AP. The timing of spinal stabilization in polytrauma and in patients with spinal cord injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:685–689. doi:10.1097/MCC.0b013e328319650b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hides JA, Lambrecht G, Richardson CA, et al. The effects of rehabilitation on the muscles of the trunk following prolonged bed rest. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:808–818. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1491-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bailey CS, Urquhart JC, Dvorak MF, et al. Orthosis versus no orthosis for the treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurologic injury: a multicenter prospective randomized equivalence trial. Spine J. 2014;14:2557–2564. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Shamji MF, Roffey DM, Young DK, Reindl R, Wai EK. A pilot evaluation of the role of bracing in stable thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurological deficit. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2014;27:370–375. doi:10.1097/BSD.0b013e31826eacae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Stadhouder A, Buskens E, Vergroesen DA, Fidler MW, de Nies F, Oner FC. Nonoperative treatment of thoracic and lumbar spine fractures: a prospective randomized study of different treatment options. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:588–594. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181a18728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G, et al. The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. I. Paraplegia. 1969;7:179–192. doi:10.1038/sc.1969.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kubosch D, Kubosch EJ, Gueorguiev B, et al. Biomechanical investigation of a minimally invasive posterior spine stabilization system in comparison to the Universal Spinal System (USS). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:134 doi:10.1186/s12891-016-0983-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wang H, Li C, Liu T, Zhao WD, Zhou Y. Biomechanical efficacy of monoaxial or polyaxial pedicle screw and additional screw insertion at the level of fracture, in lumbar burst fracture: an experimental study. Indian J Orthop. 2012;46:395–401. doi:10.4103/0019-5413.98827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Aebi M, Etter C, Kehl T, Thalgott J. Stabilization of the lower thoracic and lumbar spine with the internal spinal skeletal fixation system. Indications, techniques, and first results of treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12:544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Westerveld LA, van Bemmel JC, Dhert WJ, Oner FC, Verlaan JJ. Clinical outcome after traumatic spinal fractures in patients with ankylosing spinal disorders compared with control patients. Spine J. 2014;14:729–740. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wood KB, Bohn D, Mehbod A. Anterior versus posterior treatment of stable thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurologic deficit: a prospective, randomized study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(suppl):S15–S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Korovessis P, Baikousis A, Zacharatos S, Petsinis G, Koureas G, Iliopoulos P. Combined anterior plus posterior stabilization versus posterior short-segment instrumentation and fusion for mid-lumbar (L2-L4) burst fractures. Spine. 2006;31:859–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wang ST, Ma HL, Liu CL, Yu WK, Chang MC, Chen TH. Is fusion necessary for surgically treated burst fractures of the thoracolumbar and lumbar spine? a prospective, randomized study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2646–2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]