Abstract

Background

Isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) of the young has been associated with both normal and increased cardiovascular risk, which has been attributed to differences in central systolic blood pressure and arterial stiffness.

Methods

We assessed the prevalence of ISH of the young and compared differences in central systolic blood pressure and arterial stiffness between ISH and other hypertensive phenotypes in a multi-ethnic population of 3744 subjects (44% men), aged <40 years, participating in the HELIUS study.

Results

The overall prevalence of ISH was 2.7% (5.2% in men and 1.0% in women) with the highest prevalence in individuals of African descent. Subjects with ISH had lower central systolic blood pressure and pulse wave velocity compared with those with isolated diastolic or systolic-diastolic hypertension, resembling central systolic blood pressure and pulse wave velocity values observed in subjects with high-normal blood pressure. In addition, they had a lower augmentation index and larger stroke volume compared with all other hypertensive phenotypes. In subjects with ISH, increased systolic blood pressure amplification was associated with male gender, Dutch origin, lower age, taller stature, lower augmentation index and larger stroke volume.

Conclusion

ISH of the young is a heterogeneous condition with average central systolic blood pressure values comparable to individuals with high-normal blood pressure. On an individual level ISH was associated with both normal and raised central systolic blood pressure. In subjects with ISH of the young, measurement of central systolic blood pressure may aid in discriminating high from low cardiovascular risk.

Keywords: Isolated systolic hypertension, central blood pressure, HELIUS study

Introduction

Isolated systolic hypertension (ISH), defined as systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥140 mmHg and diastolic BP <90 mmHg, is the most common hypertensive phenotype above 50 years of age.1 Although ISH is less common in adolescents and younger adults, its prevalence is increasing.2,3 In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) the overall prevalence of ISH in those under 40 years of age more than doubled, rising from 0.7% between 1988 and 1994 to 1.6% between 1999 and 2004.2 Whether ISH of the young is a benign condition caused by increased systolic BP amplification with increased brachial, but normal central systolic BP,4–6 or results from increased arterial stiffness and larger stroke volume that may evolve into sustained hypertension is debated.7–9 In line, it is still unclear whether BP lowering therapy would benefit individuals with ISH of the young.10,11 The Chicago Heart Association study showed that ISH in young and middle-aged subjects was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality compared with optimal BP during a 31-year follow-up, but with a large difference between men and women.12 Young and middle-aged women with ISH had a higher risk of CVD than men, who had a similar risk compared with subjects with high-normal BP. It is conceivable that these gender disparities may be attributable to differences in central systolic BP, which is a potentially better predictor for CVD than brachial BP.13 In addition, age-dependent differences in pulse pressure amplification likely contribute to CVD risk.4,14 This is supported by data from the Framingham Heart Study showing that, in contrast to the elderly, pulse pressure is not associated with coronary events below age 5015 and is inversely related to coronary disease in men aged <40 years.16 This probably results from increased systolic pressure amplification in the setting of low central systolic BP.17 Finally, while ethnic differences in CVD are well recognized,18–20 data regarding differences in hypertensive phenotypes, including ISH, in young to middle-aged subjects from different ethnic groups are lacking. We previously identified substantial ethnic differences in BP and central haemodynamics.21,22 This may also affect the prevalence of hypertension and ISH of the young in particular.

In the present study we compared differences in the prevalence of ISH and other hypertensive phenotypes and explored its association with central BP, arterial stiffness and stroke volume among subjects aged <40 years in a multi-ethnic population.

Methods

Study population

This study was performed using baseline data of the HEalthy LIfe in an Urban Setting (HELIUS) study. HELIUS is a large-scale, multi-ethnic prospective cohort study that focuses on public health among six major ethnic groups residing in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. In HELIUS, participants are sampled randomly from municipal records, stratified by ethnicity. Details of the HELIUS study have been previously described.23,24 HELIUS is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam. All participants gave written informed consent. We used baseline data that were collected between January 2011 and November 2015, of 5400 subjects aged <40 years (40% men, mean age 29 ± 6 years). Subjects who were on antihypertensive therapy (n = 93) were excluded, leaving 5307 subjects. Of these, a total of 3744 participants successfully completed all haemodynamic assessments, consisting of 793 Dutch, 433 South-Asian Surinamese, 538 African Surinamese, 755 Turkish, 857 Moroccan and 368 Ghanaian origin participants. Missing data were primarily due to logistic reasons, or inability to obtain valid readings.

Study procedures

Study participants visited the research location in the morning after an overnight fast and refrained from smoking in the morning prior to the visit. Information regarding demographics, smoking behaviour and history of disease was obtained by questionnaire. Participants were asked to bring their prescribed medications to the physical examination, and these were coded according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification. Blood pressure was calculated as the average of two seated brachial BP readings, after 5 min of rest, using a semi-automated, validated sphygmomanometer (Microlife WatchBP Home, Microlife AG, Switzerland). Blood samples were taken while fasting. Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level ≥7.0 mmol/l, or the use of glucose lowering medication.

Blood pressure stratification

All subjects were stratified into exclusive blood pressure categories according to their seated brachial BP values. We defined optimal BP as <130/<85 mmHg, high-normal BP as 130–140/85–90 mmHg, ISH as ≥140/<90 mmHg, isolated diastolic hypertension as <140/≥90 mmHg and combined systolic and diastolic hypertension as ≥140/≥90 mmHg.

Central blood pressure and augmentation index

The Arteriograph system (Tensiomed Kft., Budapest, Hungary) was used to assess central BP, pulse wave velocity (PWV) and augmentation index (AIx) in supine position after at least 10 min of rest. The Arteriograph system is an operator-independent, non-invasive device that applies an oscillometric, occlusive technique by use of an upper-arm cuff to register brachial pressure curves. PWV is calculated from the return time of reflected pressure waves and the manually measured jugulo-symphisic distance. Its methodology and validation are described in detail elsewhere.25–27 Arteriograph has a close correlation with the widely applied SphygmoCor system (AtCor Medical Pty Ltd, West Ryde, Australia) for AIx (r = 0.89, p < 0.001),27 and a close correlation with invasively measured AIx (r = 0.90, p < 0.001), central BP (r = 0.95, p < 0.001) and PWV (r = 0.91, p < 0.001).26 Arteriograph PWV values are also comparable to values obtained by magnetic resonance imaging.28 AIx was additionally standardized to 75 beats/min (AIx@hr75).29 All Arteriograph measurements were performed in duplicate and the results were averaged for further analysis.

Haemodynamics

Haemodynamics were assessed by volume-clamp photoplethysmography using the Nexfin™ device30 (Edwards Lifesciences BMEYE, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). This device uses the Finapres method31–33 to continuously and non-invasively record finger arterial BP and reconstruct brachial BP.34,35 Finapres recordings were made at 200 Hz with a finger-cuff placed around the mid-phalanx of the third finger, with subjects in a supine position. Mean arterial pressure was the true integral of the arterial pressure wave of one beat divided by the corresponding inter-beat interval. Stroke volume was determined by the pulse contour method (Nexfin CO-trek).36 Cardiac output was stroke volume divided by the inter-beat interval. Systemic vascular resistance was the ratio of mean arterial pressure and cardiac output. All Nexfin haemodynamic parameters were calculated from the average of a 1-min period of stable recording.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 20.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Baseline differences between different hypertensive phenotypes were compared using chi-square for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Pair-wise comparisons were performed according to least-significant difference. To further study differences in central and brachial BP in subjects with ISH, we performed linear regression analyses, stratified by gender groups and subdivided subjects with ISH into tertiles of systolic blood pressure amplification (i.e. difference between central and brachial systolic BP). Spline interpolation was used to depict age-related changes in central and brachial BP by BP category. We considered a two-sided p-value < 0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

Results

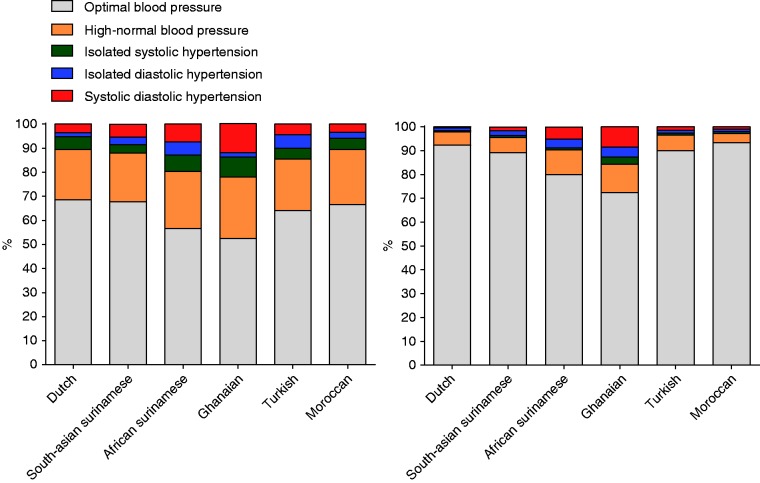

The overall prevalence of ISH was 2.7%, with a five-fold higher prevalence in men (5.2%) compared with women (1.0%). Figure 1 shows the prevalence of the different hypertensive phenotypes by gender and ethnicity. The prevalence of any form of hypertension was significantly higher in subjects of African Surinamese (11.8%) and Ghanaian (15.3%) origin compared with all other ethnic groups, who had an overall prevalence of 6.8%. The highest prevalence of ISH was observed in subjects of African descent, with a prevalence of 8.6% in Ghanaian and 7.0% in African Surinamese men, while the prevalence of ISH in women was highest in Ghanaian women (2.7%).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of different hypertensive phenotypes in men (left panel) and women (right panel) aged <40 years, by ethnic group.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects by hypertensive category are depicted in Table 1. Subjects with ISH had the greatest height, were younger, had a lower body mass index (BMI) and cholesterol than those with combined hypertension or diastolic hypertension, while they were comparable in age, BMI and cholesterol with subjects having high-normal BP. Diabetes was more prevalent in any of the hypertensive phenotypes, compared with subjects with high-normal or optimal BP.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to hypertensive phenotype.

| Optimal BP | High-normal BP | ISH | Isolated diastolic hypertension | Combined hypertension | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = | 2901 | 500 | 109 | 85 | 149 | |

| Men, % | 38 | 72 | 83 | 58 | 60 | |

| Age, years | 28.7 ± 6.1 | 30.2 ± 5.8a | 29.8 ± 6.5a | 32.6 ± 5.2a,b,c | 33.8 ± 4.8a,b,c | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 114.3 ± 8.8 | 132.6 ± 4.2a | 145.1 ± 5.8a,b | 132.8 ± 4.7a,c | 153.7 ± 12.0a,b,c | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 70.8 ± 6.65 | 81.7 ± 5.5a | 81.6 ± 5.9a | 92.6 ± 2.1a,b,c | 99.1 ± 7.5a,b,c | <0.001 |

| Height, cm | 169 ± 10 | 174 ± 10a | 177 ± 10a,b | 172 ± 10a,b,c | 172 ± 10a,b,c | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.4 ± 4.1 | 27.2 ± 4.6a | 27.7 ± 5.1a,b | 28.6 ± 6.0a,b | 30.3 ± 5.7a,b,c | <0.001 |

| Smoking, % | 27 | 27 | 27 | 35 | 23 | NS |

| Diabetes, % | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.8a,b | 3.5a,b | 5.4a,b | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol, mmol/l | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 0.9a | 4.7 ± 0.9a | 4.9 ± 1.0a | 5.0 ± 0.9a,b,c | <0.001 |

Systolic and diastolic BP are the average two consecutive, seated measurements.

p < 0.05 pairwise comparison versus optimal BP.

p < 0.05 pairwise comparison versus high-normal BP.

p < 0.05 pairwise comparison versus ISH.

BP: blood pressure; ISH: isolated systolic hypertension; BMI: body mass index.

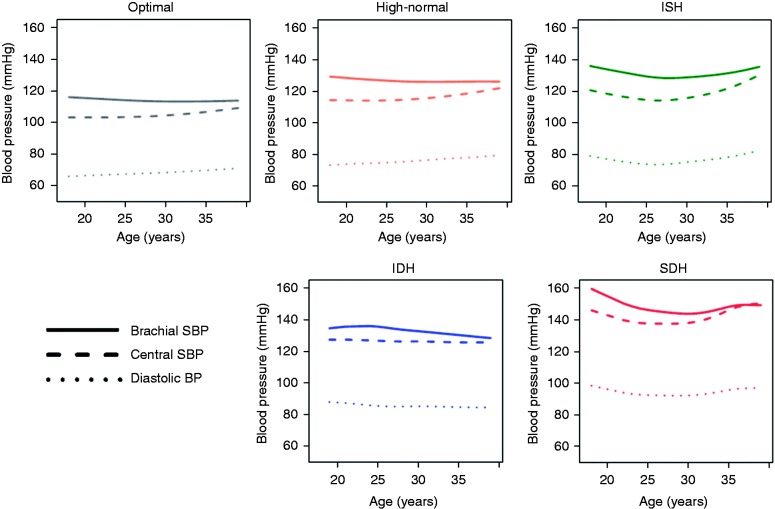

Central systolic BP was lower in subjects with ISH (119.6 ± 13.1 mmHg) than in subjects with diastolic hypertension (126.0 ± 11.8 mmHg) or combined hypertension (144.9 ± 18.5 mmHg, all p < 0.05). Systolic pressure amplification was largest in subjects with ISH (11.9 ± 7.0 mmHg) compared with those with diastolic hypertension (5.3 ± 7.0 mmHg) or combined hypertension (5.3 ± 7.0 mmHg), as well as compared with subjects with optimal BP (9.2 ± 5.5 mmHg) or high-normal BP (9.8 ± 6.5 mmHg). Figure 2 shows central systolic BP and brachial systolic BP depicted by age for the various hypertensive phenotypes. Systolic BP amplification decreased with age in all hypertensive phenotypes. Systolic blood pressure amplification was largest in subjects with ISH and high-normal BP, while individuals with diastolic and combined hypertension had the lowest systolic blood pressure amplification. Table 2 shows the haemodynamic variables by hypertensive phenotype. Subjects with ISH had significantly lower AIx, AIx@hr75, and larger stroke volume compared with all other categories, while systemic vascular resistance was significantly lower in subjects with ISH compared with those with diastolic and combined hypertension, high-normal or optimal BP. Subjects with ISH had a similar PWV compared with subjects with high-normal BP. PWV was lower in subjects with optimal BP and higher in those with diastolic or combined hypertension compared with ISH.

Figure 2.

Central and brachial SBP, by age of the hypertensive phenotypes.

ISH: isolated systolic hypertension; IDH: isolated diastolic hypertension; SDH: combined systolic and diastolic hypertension; BP: blood pressure; SBP: systolic BP

Table 2.

Haemodynamics according to hypertensive phenotype.

| Optimal BP | High-normal BP | ISH | Isolated diastolic hypertension | Combined hypertension | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brachial systolic BP, mmHg | 113.9 ± 9.5 | 126.6 ± 9.3a | 131.6 ± 11.2a,b | 131.4 ± 10.3a,b | 147.6 ± 14.4a,b,c | |

| Central systolic BP, mmHg | 104.7 ± 9.7 | 116.7 ± 10.4a | 119.6 ± 13.1a,b | 126.0 ± 11.8a,b,c | 144.9 ± 18.5a,b,c | |

| Systolic BP amplification, mmHg | 9.2 ± 5.5 | 9.8 ± 6.5a | 11.9 ± 7.0a,b | 5.3 ± 7.0a,b,c | 5.3 ± 7.0a,b,c | |

| Sup. DBP, mmHg | 68.1 ± 7.4 | 76.6 ± 7.5a | 77.0 ± 8.2a | 84.9 ± 7.3a,b,c | 94.8 ± 10.1a,b,c | All |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 61.2 ± 8.6 | 61.8 ± 10.0 | 60.3 ± 8.1 | 69.0 ± 9.9a,b,c | 67.3 ± 10.0a,b,c | <0.001 |

| PWV, m/s | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 6.9 ± 1.0a | 7.0 ± 1.3a | 7.7 ± 1.7a,b,c | 8.5 ± 1.8a,b,c | |

| AIx, % | 16.2 ± 10.3 | 16.4 ± 11.9 | 13.6 ± 11.9a,b | 24.2 ± 13.2a,b,c | 30.5 ± 15.8a,b,c | |

| AIx@hr75, % | 10.3 ± 10.1 | 11.0 ± 11.9 | 8.0 ± 11.8a,b | 21.7 ± 118a,b,c | 27.2 ± 14.9a,b,c | |

| Stroke volume, ml | 99 ± 18 | 108 ± 18a | 113 ± 15a,b | 99 ± 15b,c | 103 ± 19a,b,c | |

| SVR, dyne/s per cm5 | 1213 ± 360 | 1173 ± 319a | 1162 ± 280 | 1255 ± 367b,c | 1322 ± 416a,b,c |

Measurements performed in supine position. Systolic BP amplification = brachial – central systolic BP.

BP: blood pressure; ISH: isolated systolic hypertension; Sup.: supine; DBP: diastolic BP; PWV: pulse wave velocity; AIx: augmentation index; AIx@hr75: AIx standardized to 75 beats/min; SVR: systemic vascular resistance

p < 0.05 pairwise comparison versus optimal BP.

p < 0.05 pairwise comparison versus high-normal BP.

p < 0.05 pairwise comparison versus ISH.

Table 3 shows a stratified analysis according to tertiles of systolic BP amplification in subjects with ISH. Subjects in the lowest tertile of systolic BP amplification were more often female and of Ghanaian descent, while subjects from the upper tertile of systolic BP amplification were younger, taller, had a larger stroke volume and were more frequently of Dutch and Moroccan descent. Stratification of participants with ISH by gender is provided in the Supplementary Material online.

Table 3.

ISH tertiles of systolic blood pressure amplification.

| Lower tertile | Middle tertile | Upper tertile | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 90) | 23.4% | 35.6% | 40.0% | |

| Women (n = 19) | 78.3% | 17.4% | 4.3% | |

| Dutch (n = 18) | 28% | 22% | 50% | |

| South-Asian Sur. (n = 12) | 22% | 67% | 11% | |

| African Sur. (n = 19) | 26% | 37% | 37% | |

| Ghanaian (n = 18) | 61% | 22% | 17% | |

| Moroccan (n = 24) | 28% | 28% | 44% | |

| Turkish (n = 18) | 29% | 42% | 29% | |

| Age, years | 32.5 ± 5.8 | 29.1 ± 6.4a | 27.2 ± 6.2a,b | 0.002 |

| Height, cm | 172 ± 10 | 178 ± 8a | 182 ± 7a | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 ± 5.2 | 27.0 ± 4.9 | 28.0 ± 4.9 | NS |

| Central systolic BP, mmHg | 123.7 ± 17.1 | 116.6 ± 10.6a | 116.3 ± 9.1a | 0.026 |

| Brachial systolic BP, mmHg | 128.7 ± 13.8 | 129.7 ± 10.5 | 134.4 ± 9.5a | NS |

| Systolic pressure amplification, mmHg | 4.9 ± 6.5 | 13.1 ± 1.2a | 18.1 ± 2.1a,b | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 78.4 ± 9.1 | 75.8 ± 8.5 | 75.2 ± 6.7 | NS |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 58.7 ± 8.5 | 58.4 ± 6.5 | 62.6 ± 8.8a | NS |

| PWV, m/s | 7.3 ± 1.7 | 6.4 ± 0.6a | 7.2 ± 1.3b | 0.004 |

| AIx, % | 24.7 ± 11.4 | 11.6 ± 3.7a | 3.6 ± 3.9a,b | <0.001 |

| Stroke volume, ml | 108 ± 19 | 116 ± 13a | 117 ± 12a | 0.026 |

| SVR, dyne/s per cm5 | 1258 ± 319 | 1136 ± 227a | 1058 ± 210a | 0.006 |

| Smoking | 30% | 27% | 23% | NS |

| Diabeteses | 2.3% | 4.6% | 2.3% | NS |

| Total cholesterol | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | NS |

ISH: isolated systolic hypertension; Sur.: Surinamese; BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure; PWV: pulse wave velocity, AIx: augmentation index; SVR: systemic vascular resistance

p < 0.05 pairwise comparison versus lower tertile.

p < 0.05 pairwise comparison versus middle tertile.

Discussion

We observed a high prevalence of ISH among men of different ethnic backgrounds. The prevalence of ISH in males was two-fold higher compared with previous data from NHANES, while the prevalence among females was similar.2 African descent populations had the highest prevalence of ISH and also had a much higher prevalence in diastolic or combined hypertension compared with all the other ethnic groups. However, in contrast to individuals of Dutch and Moroccan descent they had a higher systolic central BP and AIx, which is consistent with previous publications that reported a higher AIx among African descent populations.37 In subjects with ISH, increased systolic BP amplification was associated with male gender, Dutch origin, lower age, taller stature, lower AIx and larger stroke volume. In addition, women with ISH had a higher central systolic BP and AIx compared with men. Therefore, ISH of the young is a heterogeneous condition not only because of its varying prevalence among males and females of different ethnic groups, but also because it is associated with both normal and increased central systolic BP. This may have important implications for cardiovascular risk.

Evidence suggests that central BP is a stronger predictor for future CVD than brachial BP,13 and indices of wave reflection, such as AIx, have been associated with CVD independently of BP in various populations.38,39 In the Chicago Heart Association study an increased risk of CVD mortality was observed in young and middle-aged subjects with ISH compared with those with optimal BP.12 Interestingly, the relative risk of CVD associated with ISH was considerably higher in women than in men. The higher central systolic BP in women with ISH of the young as observed in our study provides a potential explanation for the gender difference in cardiovascular risk. In contrast, men with ISH had a comparable central systolic BP compared with individuals with high-normal BP and had similar PWV and cardiovascular risk, which is in line with the comparable CVD risk among men with ISH and high-normal BP in the Chicago Heart Association study.12 Given the association of central haemodynamics with CVD risk and the heterogeneity among subjects with ISH of the young, central haemodynamic assessments may potentially aid in differentiating ISH of the young with high from low CVD risk.

ISH at older age is a consequence of arterial stiffening, which leads to a steady rise in systolic BP as a result of changes in arterial wave reflection and increased systolic pressure augmentation, whereas diastolic BP falls because of loss of Windkessel-function and increased diastolic runoff. ISH is associated with a two- to four-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events, renal dysfunction and mortality in elderly subjects.40,41 In contrast, ISH of the young has been related to both an innocuous phenomenon caused by increased pulse pressure amplification (spurious hypertension) and a potentially harmful condition associated with increased arterial stiffness.10,11 Evidence for a ‘spurious’ condition is provided by observations that young, tall, fit men have exaggerated amplification of the central pressure wave and that this is accompanied by much lower central systolic BP and low CVD risk,4–6 while others have advocated that ISH in the young results from increased arterial stiffness and larger stroke volume which is more likely to transform into sustained hypertension and is accompanied by raised central systolic BP and increased CVD risk.7,9 In the present study, most subjects with ISH had low central systolic BP values and a large difference between peripheral and central systolic BP. Individuals with the lowest central systolic BP values and largest pulse pressure amplification were younger, almost exclusively men, more frequently Dutch, taller and had a larger stroke volume, while AIx and PWV were lower. This suggests that in young males, ISH is a spurious condition that is associated with low central systolic BP. In contrast, individuals with ISH and higher central systolic BP and lower systolic blood pressure amplification were older, more frequently female and of Ghanaian descent and had a higher AIx and PWV, thereby resembling ISH of older age. While we identified different phenotypes of ISH of the young, the nature of differences in systolic BP and amplification are incompletely understood. Potentially, genetic factors play a role as genetic variations associated with raised systolic BP in adulthood also predict systolic BP levels in children.42 Based on pathophysiological differences that are associated with either low or high central systolic BP, ISH of the young is likely associated with both low CVD risk and ‘true’ ISH with raised CVD risk. Estimation of central systolic BP may offer the potential to discriminate subjects with ISH who have low central BP and CVD risk from those who have high central blood pressure and increased risk of CVD.

Strengths and limitations

The most important strengths of this study include the multi-ethnic nature of the studied population. The diversity of our study population, including differences in its physiological characteristics, increases the generalizability of the study results and contributes to better understanding of the physiological differences in ISH of the young. Limitations include the cross-sectional design and the use of non-invasive measurements that have been validated in predominantly European populations. However, we assume that their physiological principles are generalizable to other ethnic groups. For obvious reasons invasive measurement techniques are not suitable in HELIUS. In addition, while relative differences are likely accurate, the extrapolation of absolute values should be done with caution. To classify the hypertensive phenotypes we used seated brachial BP readings, while the haemodynamics investigations were performed in supine position. However, as seated brachial BP readings are used for diagnosis and treatment decisions in daily practice, we consider this discrepancy to be justified.

Perspectives

We identified substantial heterogeneity within a population of subjects with ISH of the young, showing both a favourable and potentially detrimental haemodynamic profile. The assessment of central haemodynamics may prove valuable to distinguish benign from harmful ISH in young subjects, particularly in men, yet prospective studies that include such investigations are required. Within HELIUS, subjects will return for long term follow-up. This could yield valuable information regarding the course of central haemodynamics in subjects with ISH.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for Isolated systolic hypertension of the young and its association with central blood pressure in a large multi-ethnic population. The HELIUS study by Daan W Eeftinck Schattenkerk, Jacqueline van Gorp, Liffert Vogt, Ron JG Peters and Bert-Jan H van den Born in European Journal of Preventive Cardiology

Author contribution

DWES, JvG, RJGP, LV and BvdB CD contributed to the conception or design of the work. DWES, JvG, RJGP, LV and BvdB contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. DWES and BvdB drafted the manuscript. DWES, JvG, RJGP, LV and BvdB critically revised the manuscript. All gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The HELIUS study is conducted by the Academic Medical Centre (AMC) Amsterdam and the Public Health Service (GGD) of Amsterdam. Both organizations provided core support for HELIUS. The HELIUS study is also funded by the Dutch Heart Foundation, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the European Union (FP-7), and the European Fund for the Integration of non-EU immigrants (EIF).

References

- 1.Franklin SS, Jacobs MJ, Wong ND, et al. Predominance of isolated systolic hypertension among middle-aged and elderly US hypertensives: Analysis based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Hypertension 2001; 37: 869–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grebla RC, Rodriguez CJ, Borrell LN, et al. Prevalence and determinants of isolated systolic hypertension among young adults: The 1999–2004 US National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey. J Hypertens 2010; 28: 15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorof JM. Prevalence and consequence of systolic hypertension in children. Am J Hypertens 2002; 15: 57S–60S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Rourke MF, Adji A. Guidelines on guidelines: Focus on isolated systolic hypertension in youth. J Hypertens 2013; 31: 649–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahmud A, Feely J. Spurious systolic hypertension of youth: Fit young men with elastic arteries. Am J Hypertens 2003; 16: 229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Rourke MF, Vlachopoulos C, Graham RM. Spurious systolic hypertension in youth. Vasc Med 2000; 5: 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McEniery CM, Franklin SS, Wilkinson IB, et al. Isolated systolic hypertension in the young: A need for clarity. J Hypertens 2013; 31: 1911–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franklin SS, Wilkinson IB, McEniery CM. Unusual hypertensive phenotypes: What is their significance? Hypertension 2012; 59: 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McEniery CM, Yasmin, Wallace S, et al. Increased stroke volume and aortic stiffness contribute to isolated systolic hypertension in young adults. Hypertension 2005; 46: 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lurbe E, Redon J. Isolated systolic hypertension in young people is not spurious and should be treated: Con side of the argument. Hypertension 2016; 68: 276–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McEniery CM, Franklin SS, Cockcroft JR, et al. Isolated systolic hypertension in young people is not spurious and should be treated: Pro side of the argument. Hypertension 2016; 68: 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yano Y, Stamler J, Garside DB, et al. Isolated systolic hypertension in young and middle-aged adults and 31-year risk for cardiovascular mortality: The Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65: 327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McEniery CM, Cockcroft JR, Roman MJ, et al. Central blood pressure: Current evidence and clinical importance. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1719–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichols WW, O’Rourke MF, Vlachopoulos C. McDonald’s blood flow in arteries, sixth edition: Theoretical, experimental and clinical principles, 6th ed London: Hodder Arnold, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin SS, Larson MG, Khan SA, et al. Does the relation of blood pressure to coronary heart disease risk change with aging? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2001; 103: 1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franklin SS, Khan SA, Wong ND, et al. The relation of blood pressure to coronary heart disease risk as a function of age: The Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35(Suppl. A): 291A–292A. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson IB, Franklin SS, Hall IR, et al. Pressure amplification explains why pulse pressure is unrelated to risk in young subjects. Hypertension 2001; 38: 1461–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agyemang C, van Oeffelen AA, Norredam M, et al. Ethnic disparities in ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage incidence in the Netherlands. Stroke 2014; 45: 3236–3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhopal R, Sengupta-Wiebe S. Cardiovascular risks and outcomes: Ethnic variations in hypertensive patients. Heart 2000; 83: 495–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu Q, Burt VL, Paulose-Ram R, et al. High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease mortality risk among U.S. adults: The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey mortality follow-up study. Ann Epidemiol 2008; 18: 302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eeftinck Schattenkerk DW, van Gorp J, Snijder MB, et al. Ethnic differences in arterial wave reflection are mostly explained by differences in body height – cross-sectional analysis of the HELIUS study ethnic differences in arterial wave reflection are mostly explained by differences in body height – cross-sectional analysis of the HELIUS Study. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0160243–e0160243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agyemang C, Kieft S, Snijder MB, et al. Hypertension control in a large multi-ethnic cohort in Amsterdam, The Netherlands: The HELIUS study. Int J Cardiol 2015; 183: 180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stronks K, Snijder MB, Peters RJ, et al. Unravelling the impact of ethnicity on health in Europe: The HELIUS study. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 402–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snijder MB, Galenkamp H, Prins M, et al. Cohort profile: The Healthy Life in an Urban Setting (HELIUS) study in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e017873–e017873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baulmann J, Schillings U, Rickert S, et al. A new oscillometric method for assessment of arterial stiffness: Comparison with tonometric and piezo-electronic methods. J Hypertens 2008; 26: 523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvath IG, Nemeth A, Lenkey Z, et al. Invasive validation of a new oscillometric device (Arteriograph) for measuring augmentation index, central blood pressure and aortic pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens 2010; 28: 2068–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jatoi NA, Mahmud A, Bennett K, et al. Assessment of arterial stiffness in hypertension: Comparison of oscillometric (Arteriograph), piezoelectronic (Complior) and tonometric (SphygmoCor) techniques. J Hypertens 2009; 27: 2186–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rezai MR, Cowan BR, Sherratt N, et al. A magnetic resonance perspective of the pulse wave transit time by the Arteriograph device and potential for improving aortic length estimation for central pulse wave velocity. Blood Press Monit 2013; 18: 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkinson IB, MacCallum H, Flint L, et al. The influence of heart rate on augmentation index and central arterial pressure in humans. J Physiol 2000; 525: 263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eeftinck Schattenkerk DW, van Lieshout JJ, van den Meiracker AH, et al. Nexfin noninvasive continuous blood pressure validated against Riva-Rocci/Korotkoff. Am J Hypertens 2009; 22: 378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wesseling KH. Finger arterial pressure measurement with Finapres. Z Kardiol 1996; 85(Suppl. 3): 38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wesseling KH. A century of noninvasive arterial pressure measurement: From Marey to Penaz and Finapres. Homeostasis 1995; 36: 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wesseling KH, de Wit B, van der Hoeven GMA, et al. Physiocal, calibrating finger vascular physiology for Finapres. Homeostasis 1995; 36: 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guelen I, Westerhof BE, van der Sar GL, et al. Validation of brachial artery pressure reconstruction from finger arterial pressure. J Hypertens 2008; 26: 1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martina JR, Westerhof BE, van Goudoever J, et al. Noninvasive continuous arterial blood pressure monitoring with Nexfin(R). Anesthesiology 2012; 116: 1092–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bogert LW, Wesseling KH, Schraa O, et al. Pulse contour cardiac output derived from non-invasive arterial pressure in cardiovascular disease. Anaesthesia 2010; 65: 1119–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chirinos JA, Kips JG, Roman MJ, et al. Ethnic differences in arterial wave reflections and normative equations for augmentation index. Hypertension 2011; 57: 1108–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chirinos JA, Kips JG, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. Arterial wave reflections and incident cardiovascular events and heart failure: MESA (Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 2170–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, O’Rourke MF, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with central haemodynamics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 1865–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izzo JL, Jr, Levy D, Black HR. Clinical Advisory Statement. Importance of systolic blood pressure in older Americans. Hypertension 2000; 35: 1021–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young JH, Klag MJ, Muntner P, et al. Blood pressure and decline in kidney function: Findings from the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13: 2776–2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jansen MA, Dalmeijer GW, Visseren FL, et al. Adult derived genetic blood pressure scores and blood pressure measured in different body postures in young children. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017; 24: 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for Isolated systolic hypertension of the young and its association with central blood pressure in a large multi-ethnic population. The HELIUS study by Daan W Eeftinck Schattenkerk, Jacqueline van Gorp, Liffert Vogt, Ron JG Peters and Bert-Jan H van den Born in European Journal of Preventive Cardiology