Abstract

Background:

The impact an article has on a specific field is manifested by its number of citations. The aim of this systematic review was to perform a citation analysis and identify the 100 most-cited articles in the field of minimally invasive (MI) gastrointestinal (GI) surgery.

Methods:

The Institute for Scientific Information Web of Knowledge (1945–2017) was utilised to identify the top 100 most-cited articles in the field of MI GI surgery, using 19 distinct keywords. The data extracted were number of citations, time of publication, research topic, level of evidence, authorship and country of origin.

Results:

Of the 100 most-cited articles, the number of citations ranged from 3331 to 317 citations. Most publications reported on bariatric surgery (n = 36), followed by oncology (n = 26) and hepatobiliary surgery (n = 15). The studies were published in 26 different journals with the top three journals being Annals of Surgery (n = 30), New England Journal of Medicine (n = 10) and Obesity Surgery (n = 9). The studies were conducted in 17 different countries led by the USA (n = 51), the UK (n = 9) and France (n = 6). Articles were published on all levels of evidence: level I (n = 20), Level II (n = 29), Level III (n = 8), Level IV (n = 29) and Level V (n = 14).

Conclusion:

The study revealed citation classics in the field of MI surgery. Interestingly, a high level of evidence was not significantly associated with an increased citation number.

Keywords: Bibliometric analysis, citation classics, laparoscopic surgery, minimally invasive surgery, most-cited articles

INTRODUCTION

Surgery is a medical speciality defined by its authority to diagnose, prevent or cure illnesses by means of bodily invasion. Surgery was first developed to treat traumas and injuries. The oldest evidence-supported surgical procedure is trepanation. The procedure dates back 2300 years ago and involved drilling a hole in the human skull, exposing the dura mater to treat intracranial diseases and disorders.[1] Since then, surgeons have utilised their talents to develop more sophisticated surgical techniques. In the 10th century, an Arab doctor named Albukasim was among the first to examine body orifices through developing a speculum illuminated with candlelight and mirrors. This later formed the framework for laparoscopic surgery.[2] The first laparoscopic examination of the peritoneal cavity was attempted by George Kelling in 1901, and in 1987, Mouret performed the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy on a human.[3] Since then, the laparoscopic access has become the standard of care for several gastrointestinal (GI) surgeries as the reduced invasiveness results in less post-operative pain, faster recovery and less surgery-associated problems such as incisional hernias and adhesions in the long term.

Sir William Osler was the first to introduce the triple-treat concept of physicians expanding their knowledge through the work as clinicians but by also conducting research and teaching.[4] He once said, ‘The higher the standard of education in a profession, the less marked will be the charlatanism’. Since then, the publication of evidence-based medicine has led to constantly improved treatments. The impact of a scientific publication on its specific field can be quantified by the number of citations. The Institute for Scientific Information Web of Knowledge is an online indexing and citation service; it covers articles published since 1945.[5] It is regarded as unique due to its ability to search in five different databases: Web of Science, Derwent Innovations Index, BIOSIS Previews and Journal Citation Reports. The objective of this systematic review is to convey a close inspection, of the 100 most-cited studies, in the field of minimally invasive (MI) GI surgery, to highlight leading-edge discoveries and promising areas of research as well as centres of excellence and competitive researchers specialised in the field.

METHODS

The reporting of this systematic review adheres to the PRISMA guidelines.[6]

Citation reports were provided for those articles, which were published in journals acknowledged by the Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Reports®. Articles’ topic fields were searched for the following keywords: endoscopy, laparoscopy, minimally invasive, bariatric, gastric, gastrointestinal, hepatobiliary, robotic, cholecystectomy, hernia, appendectomy, reflux disease, splenectomy, pancreatectomy, resection, fundoplication, gastrectomy, esophagectomy, surgery (The keyword surgery is a broad far-reaching keyword that covers all surgery-related articles). The topic field included the title, abstract, author keywords and keywords within a record. Peer-reviewed open-access journals were also included in the search, with no language restrictions. The search was conducted in July 2017 and comprised all articles published since 1945. Article screening and data extraction were performed by two independent investigators. Any disagreement was resolved by consulting a third reviewer.

Eligibility criteria and the allocation of articles

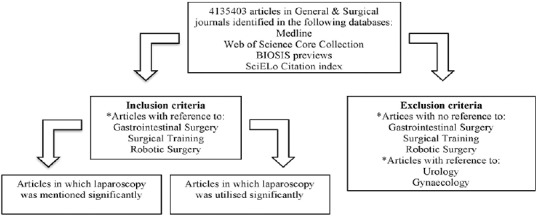

Articles from all 19 subject categories mentioned above were pooled and sorted, in the descending order, based on the number of citations. The 100 most-cited articles were considered eligible if the following inclusion criteria were met: (1) articles where laparoscopic or robotic GI surgery was mentioned or utilised significantly. Excluded were articles referring to urology, gynaecology or reporting guidelines [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating article allocation

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each of the top 100 most-cited articles: title, journal, year of publication, authorship (first and last author), department, institution and country where the study was conducted, field of research (bariatrics, hepatobiliary [HPB], hernia, upper GI, lower GI, oncology and everything else were classified as general), level of evidence (according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine); article type (experimental article, original article, review article); classification (laboratory study, survey, clinical consensus, case report, case series, cohort, randomised controlled trials [RCT], systematic review), total number of citations, citation density (total number of citations/article age).

Statistical analysis

The descriptive and bivariate statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.0. Armonk, NY, USA. Departures from normality were detected using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Depending on the normality and distribution of the data, the mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) was used. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine if the difference between the median of two or more independent groups is statistically significant. Post-hoc testing was performed, when necessary, to test for significant difference between each of the variables. The Mann-Kendall trend test was performed to test any increasing or decreasing time-dependent trends. The Spearman rank was used to determine and test for correlations between variables. A P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

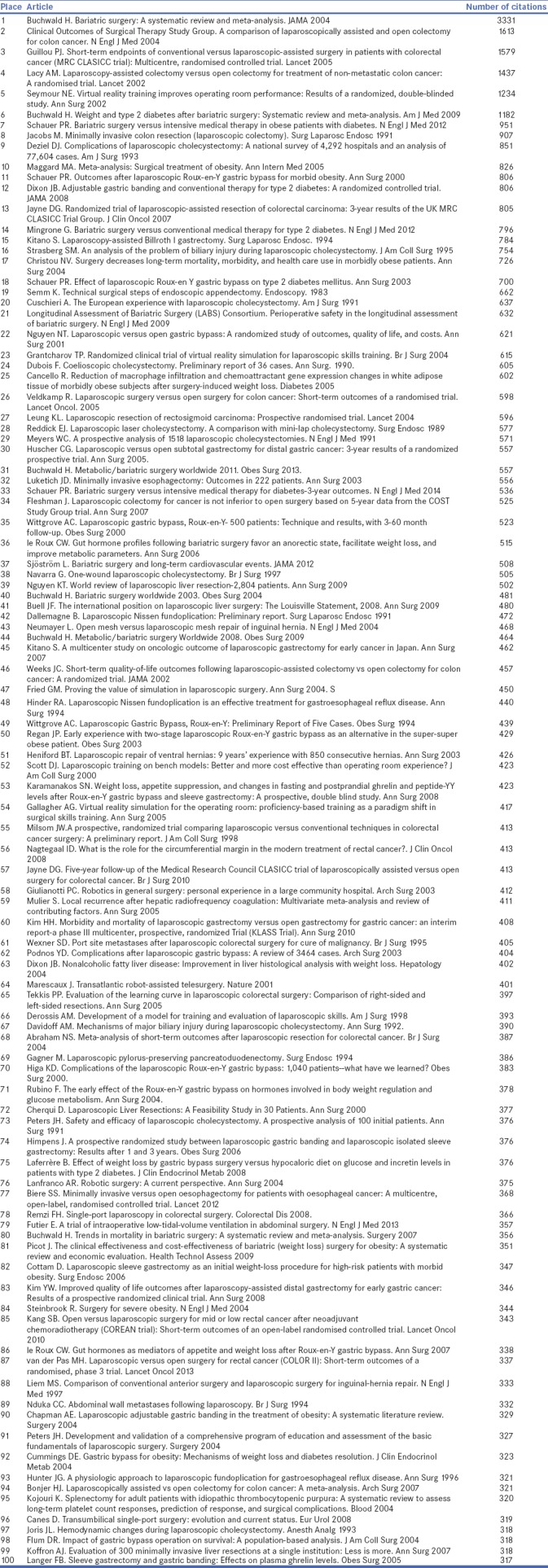

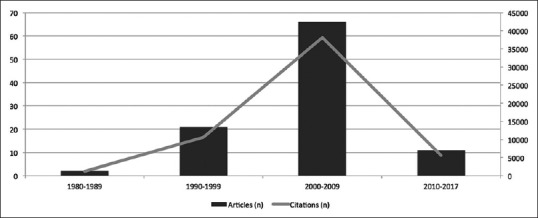

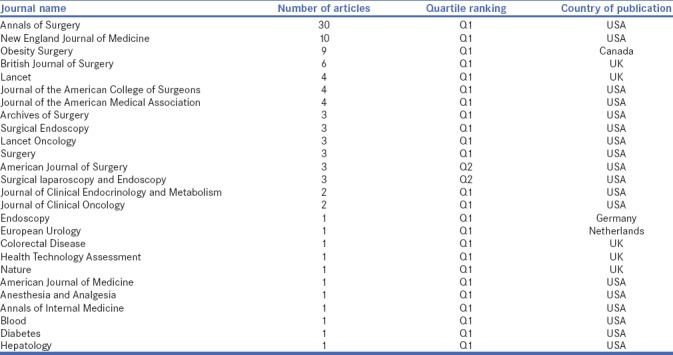

The database identified 4,141,353 different articles, published in 100 journals. The 100 top-cited articles in MI GI surgery were included [Table 1]. The top-cited articles had 3331 citations, while the lowest stood at 317 citations. The articles were published in 1983–2014 [Figure 2]. The highest total number of citations was in the 2000s (69% of total citations) followed by 1990s (19% of total citations), 2010s (10% of total citations) and 1980s (2% of total citations). The included articles were published in 26 different journals with the top three journals being Annals of Surgery (n = 30), New England Journal of Medicine (n = 10) and Obesity Surgery (n = 9). Table 2 gives a detailed overview of all the 26 journals, in which the articles were published.

Table 1.

The top 100 most-cited articles in the field of laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgery

Figure 2.

Publications per decade with number of citations per decade

Table 2.

Detailed overview of the journals in which the articles were published

Research area

The most common research area was bariatric surgery (n = 36; 39% of the total number of citations), followed by oncology (n = 27; 27% of the total number of citations), HPB (n = 15; 14% of the total number of citations), general surgery (n = 13; 11% of the total number of citations), upper GI (n = 5; 6% of the total number of citations), hernia surgery (n = 3; 2% of the total number of citations) and lower GI (n = 1; 1% of the total number of citations).

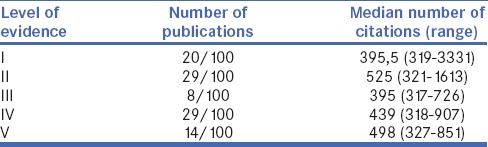

Level of evidence

Articles were published on all levels of evidence. However, only 20% of the publications were of level evidence I [Table 3]. The total number of citations for each group of level of evidence did not vary significantly (correlation coefficient = 0.109, P = 0.283). On the other hand, the citation density (average number of citations per year) varied significantly among different levels of evidence (correlation coefficient = −0.222, P = 0.026).

Table 3.

Levels of evidence and median number of citations of the top-cited articles

Article type

Most of the top 100 most-cited articles were original articles (78/100), followed by review articles (20/100) and experimental articles (2/100). The difference in the median number of citations per article, between original articles 453 (range: 317–1613), review articles 395 (range: 319–3331) and experimental articles 558 (range: 515–602), was not statistically significant (P = 0.145). Most of the studies were RCTs (n = 30), followed by non-randomised case series (n = 29), systematic reviews (n = 20), cohort studies (n = 7), case reports (n = 5), surveys (n = 5), clinical consensus (n = 2) and laboratory studies (n = 2).

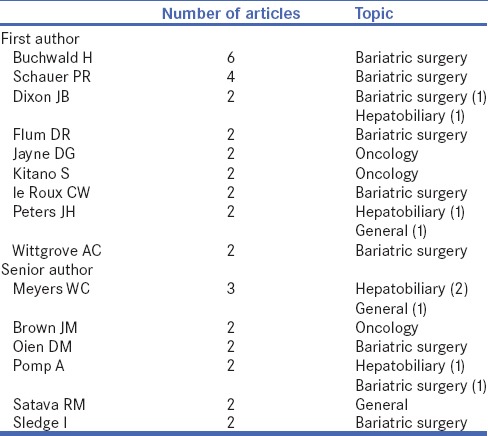

Research institutions

The 100 most-cited articles originated from 17 different countries, namely the USA (n = 51), the UK (n = 9), France (n = 6), the Netherlands (n = 6), Australia, Belgium, Canada, Italy (n = 4 each), the Republic of Korea (n = 3), Japan (n = 2), Austria, Denmark, Germany, Greece, China, Spain and Sweden (n = 1 each). Most of the articles originated from surgical departments (80%). Research institutions with three or more publications were the Cleveland Clinic (n = 7), the University of Minnesota (n = 6), University of Pittsburgh, University of Washington (n = 5 each), Imperial College London, McGill University, St James's University Hospital and University of California (n = 3 each). Frequent authors (authors with more than one first or senior authorship) contributed to 37 of the 100 most-cited articles. There were nine frequent first authors and six frequent senior authors. Frequent authors showed no more than two research areas of interest. Buchwald had the highest number of publications (n = 6), followed by Schauer (n = 4). Both showed an interest in the field of bariatric surgery. The field of oncology was led by Kitano, Jayne and Brown (n = 2 each). HPB, on the other hand, was led by Meyers (n = 2) [Table 4].

Table 4.

List of authors with more than one published article in the top 100

Further statistical analysis

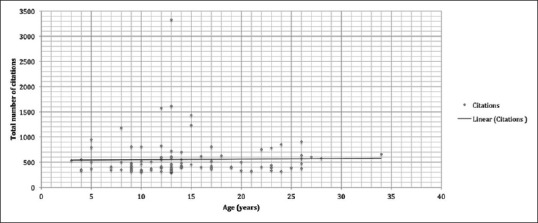

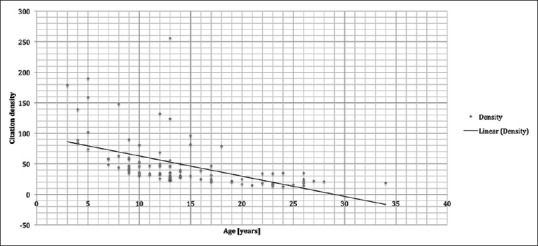

The Shapiro–Wilk test showed non-normally distributed data, P = 0.00. There was a positive, non-significant trend towards an increased total number of citations with age (correlation coefficient = 0.137, P = 0.173) [Figure 3]. On the other hand, there was a significant decrease in citation density as the article age increases (correlation coefficient = −0.723, P = 0.000) [Figure 4]. A non-significant trend has been noticed between the age of the journal and the number of articles published in the journal (correlation coefficient = 0.247, P = 0.225).

Figure 3.

Graph illustrating the total number of citation change with age

Figure 4.

Change of citation density with age

DISCUSSION

With this bibliometric analysis, the 100 most-cited articles in the field of MI GI surgery were identified. In 1994, Wittgrove performed the first laparoscopic gastric bypass and ever since the number of bariatric procedures rocketed.[7] As a consequence, the field of bariatric surgery was the most-cited topic and contributed the most articles (n = 36) led by the article published by Buchwald et al. The meta-analysis on bariatric surgery was published in JAMA in 2004 and has been cited 3.331 times since then.[8] Three more articles in the top ten reported on bariatric surgery: an RCT on bariatric surgery versus medical treatment for type 2 diabetes by Schauer et al. and two meta-analyses on bariatric surgery by Buchwald et al. and Maggard et al.[9,10,11] The second most-cited topic was surgical oncology (n = 26), led by four top ten articles. In the study by Jacobs et al., the first series of laparoscopic-assisted colectomies in 20 patients was reported.[12] The other three top ten cited articles consisted of studies providing evidence that the oncologic outcome of laparoscopic colectomies is not compromised compared to the open approach.[13,14,15] Thereby, the studies contributed to establishing the laparoscopic access as gold standard in colon cancer. HPB surgery (n = 15) was identified as third hot topic, led by articles on laparoscopic cholecystectomies and resulting biliary injuries as more advanced laparoscopic HPB procedures such as MI liver and pancreatic resections just start to gain wider acceptance. As it takes time to accumulate citations for an article, novel trends are underrepresented in this citation analysis. Thus, the rapidly growing fields of MI liver (n = 4), pancreatic (n = 1), robotic assisted (n = 3) and single-access (n = 1) surgery have not been implemented long enough. They will certainly have a more prominent role on a future list of citation classics in MI GI surgery.

The quality of the included studies, measured by the level of evidence, varied greatly. Level I evidence was only provided by 20% of the publications, whereas low-level (IV and V) evidence provided 43% of all articles. Thus, to get highly cited, articles have to be extremely relevant to their field and set the standard of care such as well-designed RCTs or articles reporting innovative ideas. These can gain great attention even if they are case series. Citation analyses in the field of visceral surgery and bariatric surgery have reported similar results, showing that all levels of evidence are represented.[16,17]

As reported in the study by Callaham et al., the impact factor of a journal is the best predictor of the number of citations of an article.[18] This was confirmed in our study as 30% of the top-cited articles were in Annals of Surgery, the journal with the highest impact in surgery, followed by the top journals in medicine namely New England Journal of Medicine and Lancet with 10% and 4% of the articles, respectively. However, compared to the citation analysis on the whole field of visceral surgery, studies were less often featured in top medicine journals (New England Journal of Medicine 38%, Lancet 13%) which may be due to the fact that laparoscopic surgery is a very specific topic with a lower relevance for physicians in general.

Over half of the articles (51%) originated from the USA. The USA remains the undisputed centre for global medical innovations not just in laparoscopic surgery but also in orthopaedics, general surgery and urology as well.[19,20,21] Factors are not only America's unmatched research activity but also its citation and reviewer behaviour as Campbell showed the tendency of authors from the UK and the USA to cite articles from their own countries.[22] Fitting into the renowned paradigm in which American journals have the propensity to accept papers from the USA, 42 of the 51 articles originating from the USA were published in American journals.

The citation analysis has several limitations. Even though the 19 keywords covered the whole spectrum of GI surgery, articles may have been missed. The analysis is furthermore limited by the fact that the older the article, the more time it had to get cited. In this study, 90% of the articles were published before 2010 and new innovations in laparoscopic surgery are under-represented in bibliometric studies.

It has to be questioned if citation numbers are a valid way to judge research. This intriguing issue was studied by Ioannidis et al. as they showed a strong relationship between high number of citations and the influence of the work.[23] However, the citation of an article is influenced by various factors: journal preferences when citing, the tendency to cite highly cited articles and the author's reputation, all of which work against the number of citations being an equitable reflector of the quality and impact of the work. Novel tools such as tweets, likes and publication downloads depict the social media impact and popularity of an article and interestingly may even predict highly cited articles within the first 3 days of article publication.[24] Therefore, traditional citation metrics will be complemented by novel social impact measures to value research.

CONCLUSION

The present study revealed citation classics in the field of laparoscopic GI surgery and identified hot topics, important discoveries and relevant contributors. Furthermore, it was shown that the number of citations does not translate into level of evidence and it should be kept in mind that bibliometric studies have several limitations.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rifkinson-Mann S. Cranial surgery in ancient Peru. Neurosurgery. 1988;23:411–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198810000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vorst AL, Kaoutzanis C, Carbonell AM, Franz MG. Evolution and advances in laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7:293–305. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i11.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spaner SJ, Warnock GL. A brief history of endoscopy, laparoscopy, and laparoscopic surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1997;7:369–73. doi: 10.1089/lap.1997.7.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone MJ. The wisdom of Sir William Osler. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:269–76. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(95)80034-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wouters P. Eugene garfield (1925-2017) Nature. 2017;543:492. doi: 10.1038/543492a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittgrove AC, Clark GW, Tremblay LJ. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y: Preliminary report of five cases. Obes Surg. 1994;4:353–7. doi: 10.1381/096089294765558331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, et al. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP, Pothier CE, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1567–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Jensen MD, Pories WJ, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122:248–56.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, Maglione M, Sugerman HJ, Livingston EH, et al. Meta-analysis: Surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:547–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs M, Verdeja JC, Goldstein HS. Minimally invasive colon resection (laparoscopic colectomy) Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:144–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group. Nelson H, Sargent DJ, Wieand HS, Fleshman J, Anvari M, et al. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2050–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, et al. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): Multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, Castells A, Taurá P, Piqué JM, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2224–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller M, Gloor B, Candinas D, Malinka T. The 100 most-cited articles in visceral surgery: A systematic review. Dig Surg. 2016;33:509–19. doi: 10.1159/000446930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad SS, Ahmad SS, Kohl S, Ahmad S, Ahmed AR. The hundred most cited articles in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25:900–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callaham M, Wears RL, Weber E. Journal prestige, publication bias, and other characteristics associated with citation of published studies in peer-reviewed journals. JAMA. 2002;287:2847–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.21.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rüegsegger N, Ahmad SS, Benneker LM, Berlemann U, Keel MJ, Hoppe S, et al. The 100 most influential publications in cervical spine research. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:538–48. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paladugu R, Schein M, Gardezi S, Wise L. One hundred citation classics in general surgical journals. World J Surg. 2002;26:1099–105. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hennessey K, Afshar K, Macneily AE. The top 100 cited articles in urology. Can Urol Assoc J. 2009;3:293–302. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell FM. National bias: A comparison of citation practices by health professionals. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1990;78:376–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ioannidis JP, Boyack KW, Small H, Sorensen AA, Klavans R. Bibliometrics: Is your most cited work your best? Nature. 2014;514:561–2. doi: 10.1038/514561a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eysenbach G. Can tweets predict citations? Metrics of social impact based on twitter and correlation with traditional metrics of scientific impact. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e123. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]