Abstract

Background:

Obesity is a risk factor for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTE is the most common cause of mortality in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. There is considerable variation in practice regarding methods, dosages and duration of prophylaxis in this patient population. Most of the literature is based on Western patients and specific guidelines for Asians do not exist.

Methods:

We conducted a web-based survey amongst 11 surgeons from high-volume centres in Asia regarding their DVT prophylaxis measures in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. We collected and analysed the data.

Results:

The reported incidence of DVT and VTE ranged from 0% to 0.2%. Most surgeons (63.64%) preferred to use both mechanical and chemoprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin being the most preferred form of chemoprophylaxis (81.82%). There was an equal distribution of weight-based, body mass index-based and fixed-dose regimens. Duration of chemoprophylaxis ranged from 3–5 days after surgery to 2 weeks after surgery. For high-risk patients, 60% surgeons preferred to start chemoprophylaxis at least 1 week before surgery. Routine use of inferior vena cava filters in high-risk patients was not preferred with some surgeons adopting a selective use (36.36%).

Conclusion:

The purpose of this survey was to understand the trends in DVT prophylaxis amongst different high-volume bariatric centres in Asia and to relate the same with the existing literature on the different steps in prophylaxis. There is, however, a need for consensus guidelines for DVT prophylaxis in Asian obese.

Keywords: Asian obese, bariatric surgery, deep vein thrombosis survey, inferior vena cava filters, thromboprophylaxis

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is both an independent and additive risk factor for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and venous thromboembolism (VTE).[1,2] All patients undergoing bariatric surgery fall under moderate to high risk for development of DVT and VTE. Obesity confers a hypercoagulable state due to increased levels of coagulation factors VII and VIII, thrombin, fibrinogen, tissue factor, von Willebrand factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 leading to higher VTE risk. Other factors which may also contribute to hypercoagulability include poor glycaemic control, dyslipidaemia, inflammation, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and impaired venous return.[3,4] The incidence of VTE in various bariatric surgery series is reported to range from 1% to 5.4% following open surgery and <1% following laparoscopic surgery. The importance of VTE lies in the fact that it is the leading cause of mortality in patients undergoing bariatric surgery.[5]

There are various modalities of DVT prophylaxis including mechanical prophylaxis methods, chemoprophylaxis agents and inferior vena cava (IVC) filters. There are also various dosage regimens being followed throughout the world with no clear standardisation. The Asian venous thromboembolism guidelines (2012) recommend that patients undergoing bariatric surgery require both properly fitting mechanical thromboprophylaxis measures and chemoprophylaxis. It also states that higher dosage of chemoprophylaxis (low-molecular-weight heparin [LMWH]) to be administered compared to normal weight patients and consideration should be given to extended duration of prophylaxis.[6] However, there are no clearly established guidelines regarding the basis of dosage (body mass index [BMI] based/weight based) and for the duration of prophylaxis. These Asian guidelines are also based on Western literature.[7] There is some evidence suggesting that VTE complications are relatively less common amongst Asians as compared to their Western counterparts.[4,8] It has been suggested that peak anti-Xa levels of 0.2–0.5 IU/ml may be considered as an indicator of adequate dosage.[9] However, measuring anti-Xa levels to monitor prophylaxis is neither practical nor necessary.

Standardisation of methods, dosages and duration of thromboprophylaxis is essential. Undertreatment may lead to increased incidence of VTE and overtreatment may need to bleeding-related complications and higher financial burden on the health-care system. Keeping in mind ethnic variations in VTE risk, Asian patients may, possibly, require a lower dosage of thromboprophylaxis but the risk–benefit ratio needs to be established.

To understand the variations in VTE protocols being followed in different Asian countries and its impact on VTE incidence, we conducted a survey amongst selected bariatric surgeons in Asia regarding their practices and analysed the existing review of literature relating to the same.

METHODS

We sent a web-based survey consisting of 19 questions via Survey Monkey to 15 bariatric surgeons from high-volume centres in Asian countries. Of the 15 surgeons, 11 responded to this survey. Countries included in this survey are Abu Dhabi, China, Dubai, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Kuwait, Singapore, Thailand and Turkey.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and entered into Excel (Microsoft Corp., USA). The responses to questions were reported as frequencies or percentages. Descriptive statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 16.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago).

RESULTS

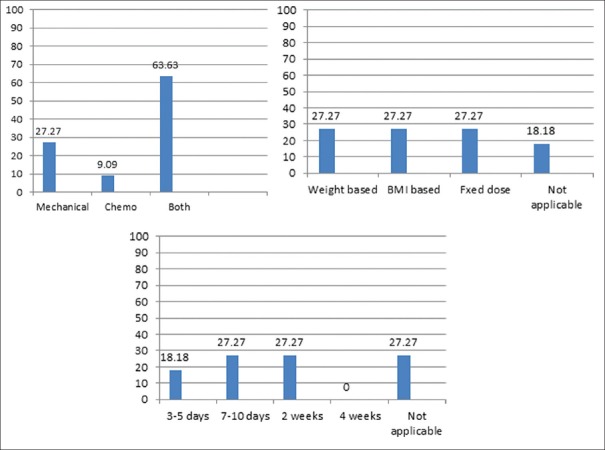

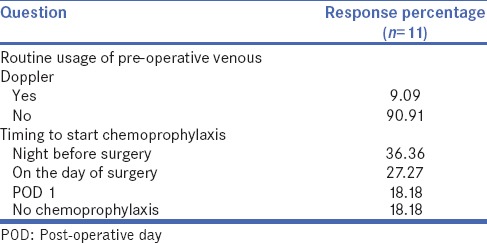

The incidence of VTE reported by all the surgeons ranged from 0% to 0.2% with more than 50% surgeons reporting 0% incidence. Table 1 shows the usage of preoperative venous Doppler for detecting pre-existing DVT and also shows the preferred timings of commencement of thromboprophylaxis. The preferences of type of prophylaxis, dosages and duration of chemoprophylaxis were considerably variable [Table 2 and Figure 1]. With regard to use of mechanical prophylaxis, most surgeons use sequential compression devices (SCDs) routinely and make the patients ambulate early. Most surgeons make the patients ambulate on the day of surgery within 4–6 h [Table 2].

Table 1.

Preference of use of pre-operative venous Doppler and timing of commencement of thromboprophylaxis

Table 2.

Types dosages and duration of thromboprophylaxis preferred by surgeons

Figure 1.

(i) Preference of surgeons (%) with regard to type of thromboprophylaxis. (ii) Preference of surgeons (%) with regard to basis of dosages. (iii) Preference of surgeons (%) with regard to duration of chemoprophylaxis

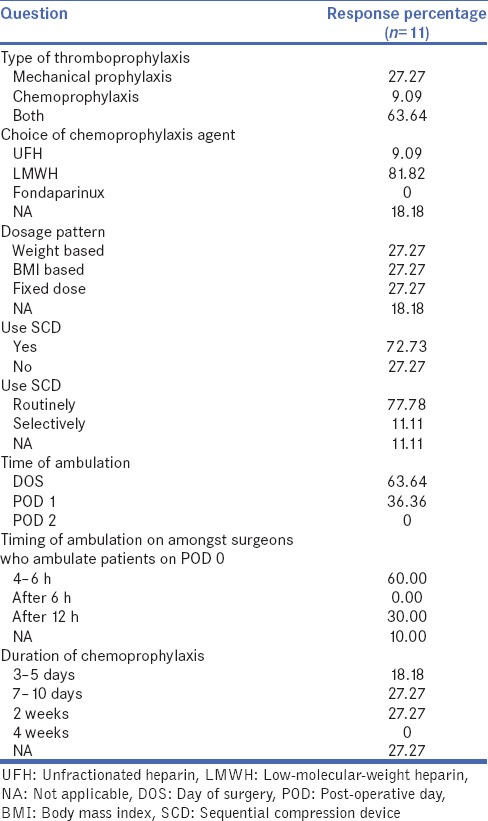

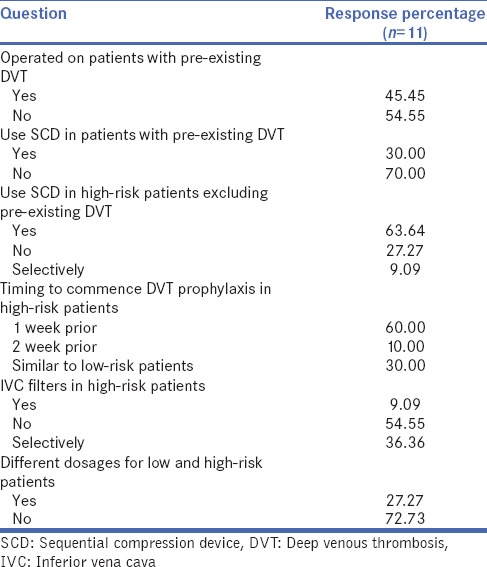

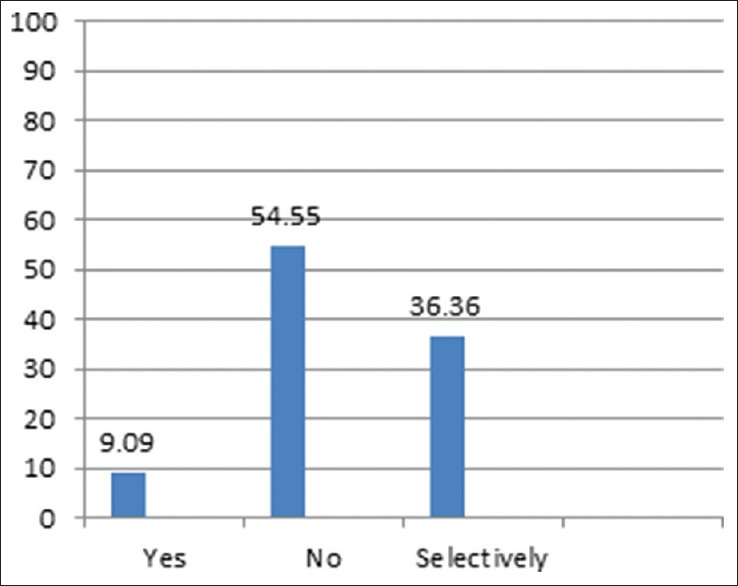

We included questions, as mentioned in Table 3, regarding modifications in DVT prophylaxis in patients who are at high risk of VTE in general and those who had pre-existing DVT in particular. 70% of surgeons would not use SCDs in patients with pre-existing DVT, but 30% would still use SCDs in this category of patients; however, most surgeons would prefer to use SCDs in other high-risk patients. 70% surgeons would commence DVT prophylaxis at least 1–2 weeks before surgery in the high-risk category patients, but most surgeons (72.7%) would not alter the dosages as compared to low-risk patients. Most surgeons would not use IVC filters or would use them selectively in high-risk patients [Figure 2].

Table 3.

Modifications in thromboprophylaxis measures in high-risk patients

Figure 2.

Preference of surgeons (%) regarding use of inferior vena cava filters in high-risk patients

DISCUSSION

DVT and related VTE is the leading cause of mortality following bariatric surgery. Hence, a standardised DVT prophylaxis is essential. Most bariatric surgeons use multimodality thromboprophylaxis including mechanical methods, chemoprophylaxis and early ambulation of patients but with considerable variability in dosage and duration of thromboprophylaxis, especially chemoprophylaxis. This variability stems from the fact that there are no established guidelines for the same, at least in the bariatric surgical setting. The incidence reported by all the surgeons who participated in this survey ranged from 0% to 0.2%. This incidence is considerably lower than what is reported in Western literature.

Role of pre-operative venous Doppler

Use of routine preoperative lower limb venous Doppler for screening for DVT is not well established. Patients with a history of DVT or clinically suspicious limb findings suggestive of venous insufficiency should be evaluated. The reported sensitivity and specificity of venous Doppler for diagnosing DVT are 97% and 94%, respectively.[10] We performed a study where we performed routine preoperative venous Doppler of 180 consecutive patients who underwent bariatric surgery and found that no patient had preoperative DVT and only 8% patients had superficial venous disease.[11] In our survey, routine preoperative venous Doppler was not preferred by >90% of surgeons.

Types of thromboprophylaxis

Mechanical thromboprophylaxis is commonly used along with chemoprophylaxis. Most surgeons in our survey also used both together, but some surgeons used only mechanical methods. Interestingly, in literature, only a few surgeons prefer mechanical prophylaxis alone. Frantzides et al. compared use of twice daily LMWH to use of only mechanical methods including SCD and early ambulation in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery and found that there was no difference in incidence of DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) in the two groups.[12] Clements et al. in their comparative study concluded that mechanical thromboprophylaxis was adequate for low-risk patients with short operative times.[13]

The Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient, 2013 Update – Cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (AACE/TOS/ASMBS guidelines) – state that DVT prophylaxis is mandatory for all patients undergoing bariatric surgery in the form of SCD and chemoprophylaxis with either unfractionated heparin (UFH) or LMWH within 24 h of surgery.[14] The Interdisciplinary European Guidelines on Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery also recommend both mechanical and chemoprophylaxis to be started in the peri-operative period.[15] In our survey, 63.64% surgeons opted for combined thromboprophylaxis which is similar to the above guidelines. It is rational to give combined therapy to obesity patients as most patients fall under the moderate-to-high-risk category for DVT and PE.[16,17]

Choice of chemoprophylactic agent

Commonly used chemoprophylactic agents include UFH, LMWH (e.g., enoxaparin, dalteparin) and fondaparinux. UFH has been frequently used in the bariatric surgical setting with doses ranging from 5000 to 7500 IU subcutaneously 2–3 times a day.[18] Limitation of UFH is unpredictable pharmacokinetics when given subcutaneously, which is even more exaggerated in the obese. Thus, dosages need to be adjusted as per the activated partial thromboplastin time.[19]

LMWHs are the most commonly used chemoprophylactic agents in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. They have predictable pharmacokinetics and the most commonly used molecule is enoxaparin. One concern amongst obese patients is inadequate dosages as standard fixed-dose regimens are usually sub-therapeutic for many of these patients.[20,21] Scholten et al. have compared two dosage regimens of enoxaparin, one being 30 mg twice a day and the other being 40 mg twice a day. They found that the incidence of DVT was higher (5.4%) in the low-dose group as compared to 0.6% in the high-dose group with no difference in haemorrhage rates.[22] Another study measured anti-Xa levels with similar dosage regimen as above and found that the 30 mg twice a day group had considerably lower anti-Xa levels indicating inadequate prophylaxis.[23] Fondaparinux is another agent which can be used for DVT prophylaxis. It is an anti-thrombotic agent which inhibits thrombin generation by selectively inhibiting factor Xa.[24] In the EFFORT trial, a randomised double-blind pilot trial, comparing enoxaparin with fondaparinux in bariatric surgical patients, adequate anti-factor Xa levels were more frequent with fondaparinux (74.2%) than with enoxaparin (32.4%), although DVT incidence was similar in both groups.[25]

In our survey, LMWH has come out as the preferred choice of most surgeons, but the dosage regimens show considerable variability. The dosage patterns were equally distributed as weight based, BMI based and fixed doses. Hence, clearly, there is no consensus on dosages. The HAT Committee of the UK Clinical Pharmacy Association in the NHS practice guidelines for doses of thromboprophylaxis at extremes of body weight suggests a body weight-based dosage of 40 mg once a day for <100 kg, a dosage of 40 mg twice a day for >100 kg and a dosage of 60 mg twice a day for >150 kg. There is however no Asian guidelines on dosages. Regarding fondaparinux only, one surgeon preferred to use them, only for Caucasians.

Duration of thromboprophylaxis

VTE clinically presents, most commonly, after discharge from the hospital. The incidence of VTE is 0.88% during hospitalisation which increases to 2.17% at 1 month to 2.99% at 6 months post-bariatric surgery.[26] VTE, as it is known, is a life-threatening complication and thus, duration of thromboprophylaxis post-surgery attains great importance, especially in the high-risk category. It was noted in our survey that most surgeons would start thromboprophylaxis on the night before or on the day of surgery. This was in accordance with AACE/TOS/ASMBS guidelines which states that thromboprophylaxis should be started within 24 h of surgery.[14] Surgeons also prefer to start thromboprophylaxis at least 1 week before surgery in high-risk patients. Furthermore, in our survey, most surgeons preferred to continue thromboprophylaxis for 1–2 weeks post-surgery. However, no guidelines clearly state the duration of thromboprophylaxis post-bariatric surgery.

Pre-existing deep vein thrombosis

Pre-existing DVT is a risk factor for recurrence of DVT in the post-surgical period.[4] Pre-existing DVT requires certain special precaution. The role of SCD is questionable as it has theoretical risk of old thrombus dislodgement which is, however, controversial.[27] It was interesting to note that 30% of surgeons would still use SCD in patients with pre-existing DVT.

Inferior vena cava filters

In our survey, most bariatric surgeons have not used IVC filters and those who have experience used it selectively. The use of IVC filters is controversial as they themselves pose risks with one study showing more than half patients with prophylactic IVC filters having fatal PE or complications such as filter migration and thrombosis of vena cava.[28] Another study showed longer hospital stay, higher rate of DVT as well as mortality with the use of IVC filters.[29] Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database data also showed similar results.[10] Some studies have also shown decreased risk of PE after prophylactic IVC filters.[30,31,32] The evidence available for prophylactic use of IVC filters in high-risk bariatric surgical is inadequate; thus, risks of placement of IVC filters has to be appropriately balanced against its benefits in selective patients.

CONCLUSION

This survey revealed that there are 2 groups of Asian surgeons, ones who are following DVT prophylaxis guidelines similar to Western data and ones who are following more restricted regimens. We need more intense trials, especially amongst Asian centres to develop a unified evidence-based approach to guide the bariatric surgeons.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Abdelrahman Nimeri (Abu Dhabi), Dr Alper Celik (Turkey), Dr Asim Shabbir (Singapore), Dr Chih Kun Huang (Taiwan), Faruq Badiuddin (Dubai), Dr Hui Liang (China), Dr Kazunori Kasama (Japan), Dr Salman Al-Sabah (Kuwait,) Simon Wong (Hongkong) and Dr Suthep Udomsawaengsup (Thailand) for participating in this survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stein PD, Beemath A, Olson RE. Obesity as a risk factor in venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2005;118:978–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdollahi M, Cushman M, Rosendaal FR. Obesity: Risk of venous thrombosis and the interaction with coagulation factor levels and oral contraceptive use. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:493–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allman-Farinelli M. Obesity and venous thrombosis: A review. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011;37:903–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1297369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cushman M. Epidemiology and risk factors for venous thrombosis. Semin Hematol. 2007;44:62–9. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes RM. Bariatric Surgical Practice Guide. Singapore: Springer; 2017. Perioperative venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after bariatric surgery; pp. 157–65. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liew NC, Chang YH, Choi G, Chu PH, Gao X, Gibbs H, et al. Asian venous thromboembolism guidelines: Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Int Angiol. 2012;31:501–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim W. Using low molecular weight heparin in special patient populations. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010;29:233–40. doi: 10.1007/s11239-009-0418-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zakai NA, McClure LA. Racial differences in venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1877–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsh J, Bauer KA, Donati MB, Gould M, Samama MM, Weitz JI, et al. Parenteral anticoagulants: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition) Chest. 2008;133:141S–59. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winegar DA, Sherif B, Pate V, DeMaria EJ. Venous thromboembolism after bariatric surgery performed by bariatric surgery center of excellence participants: Analysis of the bariatric outcomes longitudinal database. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raj PP, Gomes RM, Kumar S, Senthilnathan P, Parathasarathi R, Rajapandian S, et al. Role of routine pre-operative screening venous duplex ultrasound in morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. J Minim Access Surg. 2017;13:205–7. doi: 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_199_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frantzides CT, Welle SN, Ruff TM, Frantzides AT. Routine anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism prevention following laparoscopic gastric bypass. JSLS. 2012;16:33–7. doi: 10.4293/108680812X13291597716906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clements RH, Yellumahanthi K, Ballem N, Wesley M, Bland KI. Pharmacologic prophylaxis against venous thromboembolic complications is not mandatory for all laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:917–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, Garvey WT, Hurley DL, McMahon MM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient-2013 update: Cosponsored by American association of clinical endocrinologists, the obesity society, and American society for metabolic bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(Suppl 1):S1–27. doi: 10.1002/oby.20461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried M, Yumuk V, Oppert JM, Scopinaro N, Torres A, Weiner R, et al. Interdisciplinary European guidelines on metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2014;24:42–55. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandey A, Patni N, Singh M, Guleria R. Assessment of risk and prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in medically ill patients during their early days of hospital stay at a tertiary care center in a developing country. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:643–8. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s6416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caprini JA, Arcelus JI. Vein Book. Vol. 42. Elsevier; 2006. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the general surgical patient; pp. 369–80. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cotter SA, Cantrell W, Fisher B, Shopnick R. Efficacy of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in morbidly obese patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1316–20. doi: 10.1381/096089205774512690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shepherd MF, Rosborough TK, Schwartz ML. Heparin thromboprophylaxis in gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2003;13:249–53. doi: 10.1381/096089203764467153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanderink GJ, Le Liboux A, Jariwala N, Harding N, Ozoux ML, Shukla U, et al. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of enoxaparin in obese volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:308–18. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.127114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frederiksen SG, Hedenbro JL, Norgren L. Enoxaparin effect depends on body-weight and current doses may be inadequate in obese patients. Br J Surg. 2003;90:547–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scholten DJ, Hoedema RM, Scholten SE. A comparison of two different prophylactic dose regimens of low molecular weight heparin in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2002;12:19–24. doi: 10.1381/096089202321144522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowan BO, Kuhl DA, Lee MD, Tichansky DS, Madan AK. Anti-xa levels in bariatric surgery patients receiving prophylactic enoxaparin. Obes Surg. 2008;18:162–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer KA, Hawkins DW, Peters PC, Petitou M, Herbert JM, van Boeckel CA, et al. Fondaparinux, a synthetic pentasaccharide: The first in a new class of antithrombotic agents - The selective factor Xa inhibitors. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2002;20:37–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2002.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele KE, Canner J, Prokopowicz G, Verde F, Beselman A, Wyse R, et al. The EFFORT trial: Preoperative enoxaparin versus postoperative fondaparinux for thromboprophylaxis in bariatric surgical patients: A randomized double-blind pilot trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:672–83. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steele KE, Schweitzer MA, Prokopowicz G, Shore AD, Eaton LC, Lidor AO, et al. The long-term risk of venous thromboembolism following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1371–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaur M, Sinha C, Singh P, Gupta B. Identification of occult deep vein thrombosis before the placement of sequential compression devices. Indian J Anaesth. 2012;56:593–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.104593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birkmeyer NJ, Share D, Baser O, Carlin AM, Finks JF, Pesta CM, et al. Preoperative placement of inferior vena cava filters and outcomes after gastric bypass surgery. Ann Surg. 2010;252:313–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e61e4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li W, Gorecki P, Semaan E, Briggs W, Tortolani AJ, D'Ayala M, et al. Concurrent prophylactic placement of inferior vena cava filter in gastric bypass and adjustable banding operations in the bariatric outcomes longitudinal database. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:1690–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuster R, Hagedorn JC, Curet MJ, Morton JM. Retrievable inferior vena cava filters may be safely applied in gastric bypass surgery. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2277–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keeling WB, Haines K, Stone PA, Armstrong PA, Murr MM, Shames ML, et al. Current indications for preoperative inferior vena cava filter insertion in patients undergoing surgery for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1009–12. doi: 10.1381/0960892054621279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obeid FN, Bowling WM, Fike JS, Durant JA. Efficacy of prophylactic inferior vena cava filter placement in bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:606–8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]