Abstract

Context: Previous studies have shown that extracts of Zizyphus rugosa Lam. (Rhamnaceae) bark contained phytoconstituents with antidiabetic potential to lower blood glucose levels in diabetic rats. However, there has been no report on the active compounds in this plant as potential antidiabetic inhibitors.

Objective: We evaluated the α-glucosidase inhibitory and antioxidant activities of Z. rugosa extract. Moreover, the active phytochemical constituents were isolated and characterized.

Materials and methods: The α-glucosidase inhibition of crude ethanol extract obtained from the bark of Z. rugosa was assayed as well as the antioxidant activity. Active compounds (1–6) were isolated, the structures were determined, and derivatives (2a–2 l) were prepared. All compounds were tested for their α-glucosidase inhibitory (yeast and rat intestine) and antioxidant (DPPH) activities.

Results: The active α-glucosidase inhibitors (1–6) were isolated from Z. rugosa bark and 12 derivatives (2a–2 l) were prepared. Compound 2 showed the most powerful yeast α-glucosidase inhibitory activity (IC50 16.3 μM), while compounds 3 and 4 display only weak inhibition toward rat intestinal α-glucosidase. Moreover, compound 6 showed the most potent antioxidant activity (IC50 42.8 μM). The molecular docking results highlighted the role of the carboxyl moiety of 2 for yeast α-glucosidase inhibition through H-bonding.

Discussion and conclusions: These results suggest the potential of Z. rugosa bark for future application in the treatment of diabetes and active compounds 1 and 2 have emerged as promising molecules for therapy.

Keywords: Lupane-type triterpenes, lignan glycosides, flavonoid glycosides

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a group of metabolic disorders in which there are high blood glucose levels over a prolonged period (Palanisamy et al. 2011). Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a typical chronic metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycaemia in the context of insulin resistance (Kitabchi et al. 2009). Among several drug types available, α-glucosidase inhibitors have been marketed for treatment of T2DM. Most can control diabetes and its complications by suppressing blood glucose levels. So far, several α-glucosidase inhibiting drugs have been developed from natural prototypes (Moorthy et al. 2012).

Zizyphus rugosa Lam. (Rhamnaceae), locally known as ‘Ma Khwat’, is a large straggling shrub with recurved prickles mainly distributed in Laos, China (Hainan, Yunnan), India, Burma, Sri Lanka, Vietnam and Thailand. Previous phytochemical studies on this plant revealed various types of compounds, including flavonoids, alkaloids and triterpenoids (Kaennakam et al. 2013). Traditionally, its root and stem bark, leaves and flowers are used in the preparation of herbal formulations (Krishnamurthy & Sarala 2012). Several studies reported that this plant shows analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, anxiolytic, CNS depressant, cytotoxic, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties (Prashith Kekuda et al. 2011; Rambabu et al. 2011; Mohamad et al. 2013). Interestingly, it has been previously reported that the Z. rugosa bark extracts contain phytoconstituents with antidiabetic potential to lower blood glucose levels in diabetic rats (Marles & Farnsworth 1995; Mohamad et al. 2013). However, there has been no report on the identification of active compounds in this plant as potential antidiabetic inhibitors. This study was therefore carried out to search for active α-glucosidse inhibitory and antioxidant compounds from the bark of this plant. In addition, the enzyme kinetic activity, including the binding conformations and important interactions between potent inhibitors and α-glucosidse was investigated.

Materials and methods

General experimental procedures

1 D and 2 D NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 AVANCE spectrometer, and the chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm) using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard. Melting points were determined on a Fisher-Johns Melting Point apparatus. Adsorbents such as silica gel 60 (Merck) were used for column and radial (chromatotron model 7924 T, Harrison Research) chromatographies. Merck silica gel 60F254 plates were used for TLC. HRESIMS spectra were obtained using a Bruker MICROTOF model mass spectrometer. UV-visible absorption spectra were recorded using a UV-2550 (SHIMADZU) UV-Vis spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). α-Glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.20) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and 4-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (p-NPG) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Acarbose was obtained from Bayer Vitol Leverkusen, Germany. Rat intestinal acetone powder was supplied by Sigma Aldrich.

Plant material

The bark of Z. rugosa was collected from Mahasarakham province of Thailand in November 2014. The plant material was identified by Dr. Suttitra Khumkratok, a botanist at Walai Rukhavej Botanical Research Institute, Mahasarakham University, where a voucher specimen (khumkratok no. 1-13) is deposited.

Extraction and isolation

The air-dried bark of Z. rugosa (1.7 kg) was macerated with 4 L of EtOH at room temperature for five days. The solvent was evaporated to afford crude EtOH extract (178.0 g). This crude extract was subjected to vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC) over silica gel (Merck Art 7730), using successive eluents of hexane, CH2Cl2, EtOAc and MeOH, with increasing polarity to afford seven major fractions (A-G) which were then evaluated for their α-glucosidase inhibitory and antioxidant activities (Table 1). Based on the primary screening results, the active fraction D was further purified by column chromatography over silica gel using hexane-EtOAc (100:0-0:100) and MeOH as an eluent to afford three subfractions (D1-D3). Subfractions D1 and D3 were further purified using a combination of silica gel column and radial (chromatotron) chromatographies, affording two major triterpenoids (1, 0.51 g and 2, 1.94 g). Finally, active fraction G was isolated by silica gel column chromatography and eluting with CH2Cl2-MeOH (100:0-0:100) to yield three subfractions (G1-G3). Subfraction G2 was selected for purification by Sephadex LH-20 (2:8 MeOH–CH2Cl2) followed by RP-HPLC (ODS, 50:50 MeOH–H2O, UV 254 nm) to furnish 3 (2.5 mg, tR 32.4 min) and 4 (4.4 mg, tR 30.5 min). Subfraction G3 was subsequently purified by silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2-MeOH (90:10-0:100)) followed by Sephadex LH-20 (3:7 MeOH–CH2Cl2) to give 5 (4.3 mg) and 6 (2.1 mg). Their structures were identified by interpretation of their spectroscopic data (1 D and 2 D NMR and MS) as well as comparison with those reported in the literature.

Table 1.

α-Glucosidase inhibitory and antioxidant (DPPH) activities of fractions A-G.

| IC50 (mg/mL) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction | Baker’s yeast | Maltase | Sucrase | DPPH |

| A | 0.27 ± 1.41 | >1.0 | >1.0 | >10.0 |

| B | 0.19 ± 0.89 | >1.0 | >1.0 | >10.0 |

| C | 0.081 ± 0.67 | >1.0 | >1.0 | 8.76 ± 1.49 |

| D | 0.052 ± 1.23 | >1.0 | >1.0 | 2.44 ± 2.16 |

| E | 0.094 ± 0.59 | >1.0 | >1.0 | 1.47 ± 0.37 |

| F | 0.43 ± 1.75 | >1.0 | >1.0 | 0.13 ± 0.11 |

| G | 0.14 ± 1.22 | 0.12 ± 0.57 | >1.0 | 0.025 ± 1.85 |

| Acarbose | 0.34 ± 1.59 | 0.0051 ± 0.94 | 0.0071 ± 2.36 | – |

| Vitamin C | – | – | – | 0.028 ± 1.56 |

| BHT | – | – | – | 0.072 ± 0.35 |

General procedure for modification of derivatives (2a-2f)

Briefly, a compound 2 in CH2Cl2 was added triethylamine (TEA), 4-(dimethylamino) pyridine (DMAP) and various anhydrides. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The reaction was diluted by CH2Cl2, washed with brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After removal of solvent, the residue was purified on a chromatotron to give their derivatives. For more details were described in Supporting Information.

α-Glucosidase inhibition assay

The evaluation of the inhibitory activity of all compounds against yeast and rat intestinal (maltase and sucrase) α-glucosidases was applied from a previous procedure (Damsud et al. 2013). The inhibitory effect against yeast α-glucosidase was determined using the protocol previously described. Briefly, 10 μL of sample was mixed with α-glucosidase (0.1 U/mL) in 1 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The reaction mixture was added with 1 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (PNPG, 50 μL) followed by additional 20 min incubation. p-Nitrophenoxide liberated from the reaction was quantified by a microplate reader (UV 405 nm) after the addition of 1 M Na2CO3 (100 μL). The percent inhibition was deduced using the following equation.

where A1 and A0 are absorbances with and without the sample, respectively.

Moreover, previous procedure (Damsud et al. 2013) was also applied to determine inhibitory activity of isolated compounds against intestinal α-glucosidases (maltase and sucrase). Briefly, 10 μL of the test sample and substrate solution (maltose: 10 mM, 20 μL; sucrose: 100 mM, 20 μL, respectively) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) were incubated at 37 °C (20 min for maltase and 60 min for sucrase). The mixture was discontinued in boiling water for 10 min, and glucose released from the reaction was converted to quinoneimine using a commercial Glu Kit (Human, Germany). The absorbance of final product was determined at 503 nm, and percent inhibition was calculated using the aforementioned equation.

DPPH radical scavenging activity

The antioxidant activity of the extract was evaluated through the free radical scavenging effect on 2,2′-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) (Sigma) radical as previously reported (Yen & Hsieh 1997) with slight modifications. 100 μL of 0.10 mM DPPH ethanolic solution was added to 20 μL of the sample with various concentrations. The mixture was thoroughly mixed and kept in the dark for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a Sunrise microplate reader spectrophotometer.

Methods of computational analysis

Protein homology modelling and inhibitor preparation

The amino acid sequence of the yeast α-glucosidase was obtained from the Gen Bank database (GenBank CAA00532.1) (Lee et al. 2014). The BLAST search module of Discovery Studio version 2.0 (Accelrys) was used to search for the most similar three-dimensional crystal structure with yeast α-glucosidase.

It was found that the crystal structure with the pdb code of 3A4A, which has the X-ray crystallographic resolution of 1.60 Å, showed the highest identity and similarity percentage of 71.3 and 86.7, respectively (Yamamoto et al. 2010). Therefore, the pdb code: 3A4A was further used as the template for yeast α-glucosidase structure.

The Protein Modelling module of Discovery Studio version 2.0 was used to determine the three-dimensional structure of yeast α-glucosidase (Lugsanangarm et al. 2011). Ten satisfactory protein models were constructed and the justification of quality was based on the density optimization potential energy (DOPE) score (Lugsanangarm et al. 2011). The structure which showed a lowest DOPE score was selected for further study. Subsequently, the homology modelled structure was subjected for energetic relaxation using the Amber14 software package with the amber14sb force field (Case et al. 2008). The protein was energetically minimized with 1000 steps using steepest descent minimization, followed by another 2000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization. Subsequently, the protein was then solvated by TIP3P water molecules extending to 12 Å in each of the six directions: (±x, ±y, and ±z) around the protein. The periodic boundary condition was employed. Appropriate sodium counter ions were then added to neutralize the systems. Subsequently, 2000 steps of steepest descent minimization were performed on the whole system followed by 3000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization. This minimized system was used as the starting structure for the subsequent molecular docking calculations.

Compounds 1 and 2 were constructed and were energetically optimized using the MOPAC2009 program (James 2008). These optimized structures were further used in molecular docking calculation.

Molecular docking calculation

Molecular docking calculations were performed for compounds 1 and 2 using the AutoDock 4.2.6 program (Morris et al. 2009). The grid box was defined as 100 × 100 × 100 points as reported (Peng et al. 2016). It covered the amino acid residue of Asp69, Phe178, Thr215, Glu277, His351, Asp352, Arg315, Phe314 and Val410. These amino acids are believed to play critical roles in the catalytic mechanism of α-glucosidase. The 500 running numbers and Lamagian GA algorithm were employed while other parameters were set as default.

Molecular interaction analysis

The docking poses which displayed the lowest binding free energies were selected for molecular interaction analyses. The molecular conformation of compounds 1 and 2 were analyzed and depicted using Chimera software (Pettersen et al. 2004). Moreover, the hydrophobic interactions have been analyzed by using the LigPlot+ software (Cambridge, United Kingdom) (Laskowski & Swindells 2011).

Results

Bio-assay guided extraction and isolation

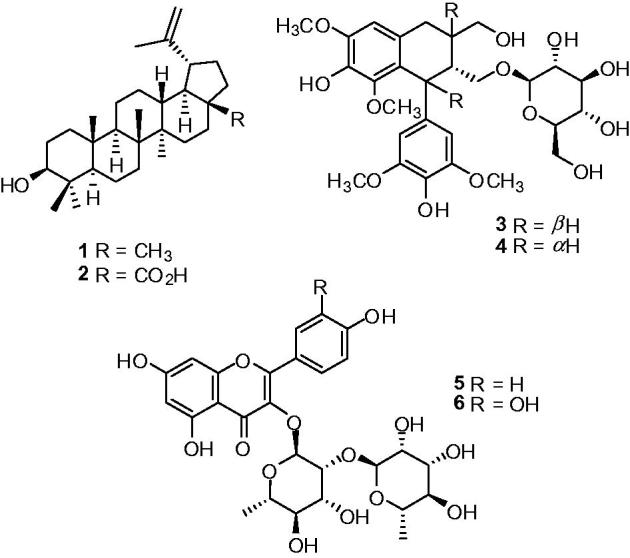

As described previously, the crude EtOH extract (178.0 g) obtained from the dried bark of Z. rugosa (1.7 kg) was fractionated to yield seven main fractions (A-G). Then, their inhibitory effects against α-glucosidases from Baker's yeast and rat intestine together with antioxidant activity were examined. Based on the bio-assay guide (Table 1), fraction D revealed the most potent activity toward baker's yeast α-glucosidase (IC50 0.052 mg/mL), while fraction G showed significant but weaker activities toward α-glucosidase from yeast (IC50 0.14 mg/mL) and intestine (maltase) (IC50 0.12 mg/mL), respectively. In addition, fraction G also exhibited potent antioxidant activity with the IC50 value of 0.025 mg/mL. Therefore, fractions D and G were selected for further isolation and afforded two triterpenoids, lupeol (1) and betunilic acid (2) (Kaennakam et al. 2013) from fraction D, two lignan glycosides, (6 S,7 R,8 R)-7α-[(β-glucopyranosyl)oxy] lyoniresinol (3) and (+)-lyoniresinol-3α-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (4) (Ohashi et al. 1994) as well as two flavonoid glycosides, kaempferol-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-α-l-rhamnopyrano side (5) and horridin (6) (Olennikov & Kashchenko 2013) from fraction G (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of isolated compounds (1-6) from active fractions D and G of Z. rugosa.

α-Glucosidase activity and kinetic study

All isolated compounds (1–6) were evaluated for their baker's yeast and rat intestinal α-glucosidase activities (Table 2). Among these compounds, compounds 1 and 2 exhibited potential yeast α-glucosidase activity with the IC50 values of 37.2 and 16.3 μM, respectively, which were superior to the positive drug (acarbose) (IC50 526 μM). On the other hand, compounds 3 and 4 (from fraction G) display only weak inhibitions toward rat intestinal α-glucosidase (maltase and sucrase) with IC50 values of 1,480 and 2,341 μM, and 373 and 1,214 μM, respectively.

Table 2.

α-Glucosidase inhibitory and antioxidant (DPPH) activities of 1–6 and 2a–2l.

| IC50 (μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Baker’s yeast | Maltase | Sucrase | DPPH |

| 1 | 37.2 ± 0.22 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2 | 16.3 ± 2.03 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 3 | >600 | 1480 ± 2.13 | 2341 ± 1.43 | 4321 ± 1.13 |

| 4 | >600 | 373 ± 1.05 | 1214 ± 2.01 | 3795 ± 0.42 |

| 5 | >600 | >3000 | >3000 | 6019 ± 1.36 |

| 6 | >600 | >3000 | >3000 | 42.8 ± 0.83 |

| 2a | 28.1 ± 0.76 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2b | 43.3 ± 0.19 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2c | 158 ± 1.22 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2d | 269 ± 3.22 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2e | 72.1 ± 1.54 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2f | 73.1 ± 0.96 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2g | 230 ± 0.11 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2h | 281 ± 0.89 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2i | 368 ± 1.64 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2j | >600 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2k | >600 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| 2l | >600 | >3000 | >3000 | >10,000 |

| Acarbose | 526 ± 1.52 | 7.9 ± 0.94 | 10.9 ± 2.36 | – |

| Vitamin C | – | – | – | 158 ± 1.90 |

| BHT | – | – | – | 328 ± 0.56 |

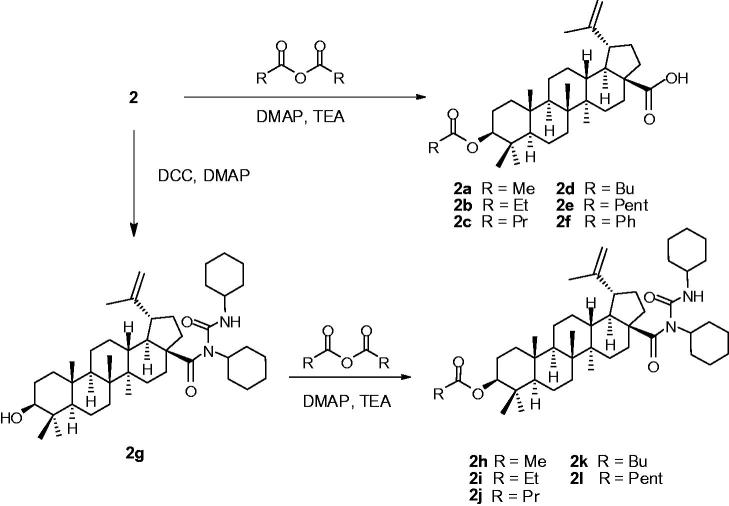

In this study, compound 2 exhibited the most powerful inhibitory activity against yeast α-glucosidase. This result drew our interest to prepare the derivatives (2a–2 l) in the course of chemical modifications (Scheme 1). All derivatives (2a–2 l) were also evaluated for their α-glucosidase activity (Table 2). Compounds 2a, 2 b, 2e and 2f exhibited potential yeast α-glucosidase activity with the IC50 values in the range of 28.1 to 73.1 μM. In addition, compounds 2c, 2d, and 2g–2i display good inhibitions toward yeast α-glucosidase with the IC50 values in the range of 158 to 368 μM, which were also superior to the positive drug (acarbose) (IC50 526 μM).

Scheme 1.

Modified reactions of betunilic acid (2).

The Lineweaver–Burk plots of a kinetic study of 2 showed linearity at each concentration examined (0.063 and 1.3 mM); all of which intersected at the second quadrant. The kinetic analysis revealed that Vmax decreased with increasing concentrations of 2 while Km increased (Figure 2S). This behaviour indicated that 2 inhibited as a mixed mode inhibitor of α-glucosidase enzyme in which noncompetitive mode (Ki 11.16 mM, Figure 3S) was preferred over competitive manner (K'i 0.019 mM, Figure 4S).

Antioxidant activity

All isolated compounds (1–6) and derivatives (2a–2l) were also evaluated for their DPPH free radical scavenging activity (Table 2). Compound 6 showed the most potent antioxidant activity with the IC50 value of 42.8 μM and indeed, this was stronger than the reference compounds (vitamin C and BHT). Compounds 3–5 likewise were weakly active (IC50 4,321, 3,795 and 6,019 μM). By contrast, other compounds (1 and 2) showed no activity.

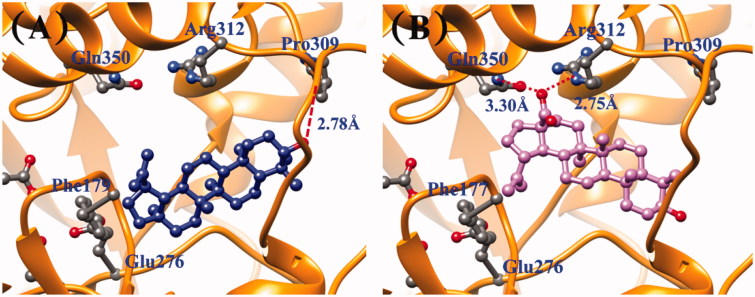

Molecular docking studies

To evaluate the activity of lupane-type triterpenoids (1 and 2) against yeast α-glucosidase, molecular docking calculations were employed. Figure 2 shows the molecular binding of 1 and 2. Compound 1 revealed the binding free energy of −5.83 kcal/mol while compound 2 exhibited −6.11 kcal/mol. These energies were in accordance with the experimental IC50 values [compounds 1 (0.037 mM) and 2 (0.016 mM)]. It was also found that compound 1 showed hydrogen bonding (H-bond) between the hydroxyl part and O (backbone) of Pro309 with the distance of 2.78 Å. This H-bond disappeared in 2. The two H-bonds, however, were formed between the oxygen atom of the carboxyl group of 2 and N (side-chain) of Arg312 and O (side-chain) of Gln350, with the distance of 2.75 and 3.30 Å, respectively.

Figure 2.

Comparison of molecular binding pose of compounds 1 (A) and 2 (B) in yeast α-glucosidase.

The hydrophobic interaction analyses revealed that compound 1 had hydrophobic interaction with Phe157, Phe178, Thr215, Leu218, Asn241, His245, Glu276, Ala278, His279 and Glu304, while compound 2 showed hydrophobic interaction with Asn241 and His245, Glu276, His279, Phe300 and Glu304 as depicted in Figure 5S.

Discussion

The selected active fractions D and G were isolated and obtained two triterpenoids (1 and 2) from fraction D, two lignan glycosides (3 and 4) and two flavonoid glycosides (5 and 6) from fraction G. All isolated compounds (1–6) were evaluated for their α-glucosidase activity, compound 2 showed most powerful inhibitory activity against yeast α-glucosidase. The above result motivated our group to investigate the structural modification and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of their derivatives (2a–2l) from that natural lupine-type (2).

In the course of chemical modifications, the series of analogues of 2 containing the modifications of C-3 and C-28 positions were prepared to yield seven new (2b and 2g–2l) and five known compounds (2a and 2c–2f). In the derivatization of 2, the amidation of 2 with DCC obtained a key intermediate (2g) and proved its structure by using single crystal X-ray crystallography (Figure 1S), followed by nucleophilic acylation of the hydroxyl group of 2g with appropriate anhydrides to afford a new series of C-3 amide ester derivatives (2h–2l). All derivatives (2a–2l) were also evaluated for their α-glucosidase activity (Table 2). Compounds 2a–2f, which lacked the hydroxyl group at C-3, showed lower activities than their originals (2) toward α-glucosidase. It is noteworthy that the hydroxyl group appeared to be involved in the yeast α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of 2. In addition, the enhancement of the side chain hydrophobicity at C-3 led to a decrease in antidiabetic activity. On the other hand, compound 2g, which lacked the carboxyl group at C-28, showed lower IC50 values against α-glucosidase than its original (2). Therefore, our finding enlightened us that the carboxyl group might be the pivotal functional group in yeast α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of 2. To envision the mechanism underlying this inhibition, a kinetic study of this potent metabolite (2) was performed. The Lineweaver-Burk plots indicated that 2 inhibited as a mixed mode inhibitor of α-glucosidase enzyme in which noncompetitive mode was preferred over competitive manner. The results of this study suggested the potential of natural compounds 1 and 2 as lead compounds for the developing antidiabetic agents; their antidiabetic properties may be related to their selectively inhibitory on Type I α-glucosidase (Baker’s yeast).

All isolated compounds (1–6) and derivatives (2a–2l) were also evaluated for their antioxidant activity. Compound 6 showed the most potent antioxidant activity and stronger than the reference agents while compounds 3–5 were weakly active. These results suggested that the greater effectiveness of 6 with o-dihydroxy group at C-3′ and C-4′ was possibly due to the presence of the catechol group which, upon donating hydrogen radicals, gives a higher stability to their radical forms (Udomchotphruet et al. 2012).

In the molecular docking calculations, compound 1 showed hydrogen bonding (H-bond) between the hydroxyl part and O (backbone) of Pro309. This H-bond disappeared in 2. The two H-bonds, however, were formed between the oxygen atom of the carboxyl group of 2 and N (side-chain) of Arg312 and O (side-chain) of Gln350. The H-bond with Arg312 energetic preferably interacted due to the negative oxygen and positively charged Arg312. This polar interaction is also reported (Ma et al. 2015; Jabeen et al. 2016) and suggesting that Arg312 may has catalytic role in the inhibition of enzyme function. (Ma et al. 2015; Jabeen et al. 2016). The –C(CH3)=CH2 group of 1 was placed far from Gln350 and Arg312 approximately of 7.5 Å. Due to a large pocket, compound 2 could flip, and this moiety pointed toward Thr215. This pose allowed H-bond forming between the carboxyl group and Arg312 and Gln350, as mentioned above. These results highlighted the role of carboxyl moiety at the C-28 position for yeast α-glucosidase inhibition through the H-bond.

Conclusions

This is the first report on mainly active α-glucosidase inhibitors and antioxidant metabolites present in the bark of Z. rugosa. Six compounds (1–6) were isolated based on bio-assay guided isolation and twelve derivatives (2a–2l) were prepared. Compound 2 showed the most powerful yeast α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, which was superior to a positive agent. On the other hand, compounds 3 and 4 exhibited weak inhibitory activity against rat intestinal α-glucosidase. In addition, compound 6 exhibited the most potent antioxidant (DPPH) activity. A subsequent investigation on the mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of compound 2 suggested that it blocked yeast α-glucosidase by mixed inhibition via competitive and noncompetitive manners. Moreover, the molecular docking studies of 1 and 2 on the binding sites of yeast α-glucosidase were performed in order to afford a molecular insight into the mode of action of these active compounds. Therefore, this study can help to support the traditional use of Z. rugosa as an antidiabetic remedy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Graduate School of Chulalongkorn University for a Postdoctoral Fellowship (Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund) to JS. We thank Dr. Sutin Kaennakam for the collection of plant materials and Dr. Suttitra Khumkratok for plant identification and deposition. Finally, KL thanks Assist. Prof. Dr. Somsak Pianwanit for fruitful discussion. We would like to acknowledge the Computational Chemistry Unit Cell, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University for the accession of DS. 2.0. We also thank Assoc. Prof. Dr. David Kreller of the Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, for his editorial comments.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham ITE, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Crowley M, Walker RC, Zhang W, et al. 2008. AMBER10. San Francisco, USA: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Damsud T, Adisakwattana S, Phuwapraisirisan P.. 2013. Three new phenylpropanoyl amides from the leaves of Piper sarmentosum and their α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. Phytochem Lett. 6:350–354. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen F, Shehzadi SA, Fatmi MQ, Shaheen S, Iqbal L, Afza N, Panda SS, Ansari FL.. 2016. Synthesis, in vitro and computational studies of 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles as potential α-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 6:1029–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James JPS.2008. Stewart computational chemistry. CO, USA: Colorado Springs. [Google Scholar]

- Kaennakam S, Sichaem J, Siripong P, Tip-pyang S.. 2013. Chemical constituents from the roots of Zizyphus rugosa Lam. Chem Nat Compd. 49:767–768. [Google Scholar]

- Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN.. 2009. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 32:1335–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy SR, Sarala P.. 2012. Determination of nutritive value of Ziziphus rugosa Lamk: a famine edible fruit and medicinal plant of Western Ghats. IJNPR. 3:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Swindells MB.. 2011. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 51:2778–2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Kim S, Kim JY, Arooj M, Kim S, Hwang S, Kim BW, Park KH, Lee KW.. 2014. Binding mode analyses and pharmacophore model development for stilbene derivatives as a novel and competitive class of α-glucosidase inhibitors. PLoS One. 9:e85827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugsanangarm K, Pianwanit S, Kokpol S, Tanaka F.. 2011. Homology modelling and molecular dynamics simulations of wild type and mutated flavodoxins from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Miyazaki F): insight into FMN–apoprotein interactions. Mol Simul. 37:1164–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Wang L, Niesen DB, Cai A, Cho BP, Tan W, Gu Q, Xu J, Seeram NP.. 2015. Structure activity related, mechanistic, and modeling studies of gallotannins containing a glucitol-core and α-glucosidase. RSC Adv. 5:107904–107915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marles RJ, Farnsworth NR.. 1995. Antidiabetic plants and their active constituents. Phytomedicine. 2:137–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad S, Frank PR, Shameem AKA, John NT, Maliekal RB.. 2013. In vivo and in vitro antidiabetic activity of Ziziphus rugosa Lam bark. IJUPBS. 2:457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy NS, Ramos MJ, Fernandes PA.. 2012. Studies on α-glucosidase inhibitors development: magic molecules for the treatment of carbohydrate mediated diseases. Mini Rev Med Chem. 12:713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ.. 2009. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 30:2785–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi K, Watanabe H, Okumura Y, Uji T, Kitagawa I.. 1994. Indonesian medicinal plants XII: four isomeric lignan-glucosides from the bark of Aegle marmelos (Rutaceae). Chem Pharm Bull. 42:1924–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Olennikov DN, Kashchenko NI.. 2013. New isorhamnetin glycosides and other phenolic compounds from Calendula officinalis. Chem Nat Compd. 49:833–840. [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy UD, Ling LT, Manaharan T, Appleton D.. 2011. Rapid isolation of geraniin from Nephelium lappaceum rind waste and its anti-hyperglycemic activity. Food Chem. 127:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Zhang G, Liao Y, Gong D.. 2016. Inhibitory kinetics and mechanism of kaempferol on α-glucosidase. Food Chem. 190:207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE.. 2004. UCSF Chimera – A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 25:1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prashith Kekuda TR, Raghavendra HL, Vinayaka KS.. 2011. Evaluation of pericarp and seed extract of Zizyphus rugosa Lam for cytotoxic activity. IJPB Arch. 2:887–890. [Google Scholar]

- Rambabu P, Venkata Ramana K, Ganapaty S.. 2011. Anti bacterial and anti fungal potential of roots of Zizyphus rugosa. IJPRD. 3:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Udomchotphruet S, Phuwapraisirisan P, Sichaem J, Tip-Pyang S.. 2012. Xanthones from the stems of Cratoxylum cochinchinense. Phytochemistry. 73:148–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Miyake H, Kusunoki M, Osaki S.. 2010. Crystal structures of isomaltase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in complex with its competitive inhibitor maltose. FEBS J. 277:4205–4214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen GC, Hsieh CL.. 1997. Antioxidant effects of dopamine and related compounds. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 61:1646–4649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.