Abstract

This study used event-related potentials (ERPs) and a modified spatial 2-back task to investigate spatial working memory in binge drinking (BD) college students. Based on the Korean version of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT-K) and Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ) scores, participants were assigned into BD (n = 25) and non-BD (n = 25) groups. The modified spatial 2-back task includes congruent, incongruent, and lure conditions and participants are required to respond as rapidly and accurately as possible to the congruent stimuli but not to the incongruent and lure stimuli. The BD and non-BD groups exhibited comparable performances on the spatial 2-back task but the BD group showed significantly larger P3 amplitudes than the non-BD group. Additionally, the non-BD group showed larger P3 amplitudes in response to the congruent stimuli compared to the incongruent and lure stimuli whereas the P3 amplitudes in the BD group did not differ significantly among the three conditions. These results indicate that the BD individuals exerted greater effort to maintain performance levels comparable to non-BD individuals and that they were less efficient in differentiating or allocating attentional resources between relevant and irrelevant information.

Introduction

Binge drinking (BD), a pattern of excessive alcohol consumption followed by a period of abstinence, is defined on the basis of the quantity, frequency and speed of alcohol consumption. For example, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [1] defined BD as a pattern of drinking alcohol that brings blood alcohol concentration levels to 0.08 g/dL, which typically occurs after 4 drinks for women and 5 drinks for men in about 2 hours. BD, which has detrimental effects on health and social functioning [2–4], is particularly prevalent among college students [5,6]; it increases the likelihood of the development of an alcohol use disorder (AUD,[7]). Additionally, structural and functional brain abnormalities [8] and cognitive dysfunction [9,10] have been observed in individuals with BD.

Spatial working memory can be defined as the temporary maintenance and manipulation of spatial information [11,12] that affects higher cognitive functions such as inhibition, problem-solving, and goal-directed behavior [13,14]. Neuroimaging studies have revealed that the prefrontal and parietal cortices are involved in spatial working memory. For example, increased activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, posterior parietal cortex, and cerebellum is observed in normal controls during the performance of a spatial working memory task [15,16]. More specifically, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is involved in the online maintenance and manipulation of spatial information while the parietal cortex is involved in the storage of spatial information [17,18].

Because chronic alcohol consumption is associated with dysfunction of the prefrontal and parietal cortices, many studies have investigated spatial working memory deficits in patients with AUD [19–22]. Studies that investigated spatial working memory in patients with AUD using neuropsychological assessments revealed that AUD patients perform significantly less well than normal controls [23,24]. Additionally, AUD patients exhibit decreased activity in the bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal and parietal cortices while performing spatial working memory tasks [20,21,25].

The spatial n-back task is widely used to evaluate spatial working memory as it requires participants to determine whether a current stimulus is in the same or a different location as a stimulus presented n trials earlier [26,27]. Studies investigating spatial working memory using spatial n-back tasks have shown that AUD patients exhibit significantly lower accuracy than normal controls [21,28]. Several recent studies modified the original n-back task to assess interference control [29,30], which is defined as the ability to inhibit information that is irrelevant to the task, because it plays an important role in working memory [30,31]. The modified spatial n-back task is the same as the original task in that the participant is required to determine whether the location of the current stimulus is the same as that of the stimulus presented n trials earlier. However, the modified version also includes a lure condition along with the congruent (locations of current stimulus and that presented n trials earlier are the same) and incongruent (locations of current stimulus and that presented n trials earlier are different) conditions. In the lure condition, the same stimulus is immediately represented. If the same stimulus is immediately represented, participants can misidentify the lure stimulus as a congruent one, leading to an incorrect response [29,30].

Studies investigating spatial working memory in normal controls using the modified spatial n-back task have observed significantly longer response times and lower accuracy rates in response to lure stimuli than to incongruent stimuli [30]. These results indicate that the repeatedly presented identical stimuli produce interference while the successively presented stimuli are being updated by the working memory system, which would require greater cognitive effort to control the lure stimuli. Therefore, the modified n-back task is considered more appropriate for evaluating working memory than the original task because the modified task requires the participant to control the interference, which affects working memory performance [30,31].

Studies investigating spatial working memory in individuals with BD using neuropsychological tests have reported somewhat inconsistent findings. For example, some studies found significantly worse performance by BD individuals than by non-BD individuals [32,33] while others observed comparable performances [34,35].

Contrary to behavioral findings from working memory tasks, neuroimaging studies have consistently reported that BD individuals exhibit different patterns of cerebral activation compared to those of non-BD individuals while performing such tasks [36–38]. For example, Squeglia et al. [38] observed increased activation in the frontal and anterior cingulate cortices of male adolescents with BD relative to non-BD individuals during the performance of a spatial working memory task as well as significant positive correlations between the increased activation and performance. Studies investigating verbal working memory in BD individuals observed increased activation in the supplementary premotor area [36], right superior frontal cortex, and bilateral posterior parietal cortices [37] in BD individuals compared to non-BD individuals. Taken together, these findings support the compensation hypothesis; i.e., greater activation of cortical areas associated with working memory is required for BD individuals to maintain behavioral performance comparable to non-BD individuals in working memory tasks [36–38].

Although neuroimaging studies have identified the brain areas involved in spatial working memory, these findings provide limited information about the sequential stages of spatial working memory. Event-related potentials (ERPs) are widely used to assess cognitive function, including working memory, due to the high temporal resolution associated with this technique [39]. ERPs are electrical activities elicited by time-locked stimuli that contain certain information and consist of several peaks or components of positive and negative potentials. These peaks reflect the various stages of information processing [40].

Studies that employed the n-back task and examined ERPs have consistently identified two ERP components, N2 and P3, as important in working memory [27,41]. In normal controls, the amplitude of N2, which is a negative peak observed from 170–340 ms after stimulus-onset, is larger in response to incongruent stimuli than in response to congruent stimuli [42–44]. Additionally, a larger N2 amplitude is observed in response to lure stimuli than in response to incongruent stimuli [29,43]. The N2 reflects the inhibition of inappropriate responses [29,43] or detection processing, in which a current stimulus is judged to be congruent or incongruent with the one presented n trials earlier [42].

In normal controls, the amplitude of P3, which is a positive peak that occurs from 250~550 ms after stimulus-onset, is larger in response to congruent stimuli than it is in response to incongruent stimuli [45,46]. P3 reflects the classification of congruent/incongruent stimuli [27,47] and is associated with allocation of attention during stimulus encoding/maintenance [48] or memory updating [49–51].

Few studies have investigated working memory in AUD patients and BD individuals using ERPs. Patients with AUD exhibit significant reductions in P3 amplitudes compared to normal controls [52,53] and the ERP patterns of BD individuals differ from those of non-BD individuals [54–56]. For example, Crego et al. [55] found that BD individuals exhibited larger N2 amplitudes in response to congruent stimuli than did non-BD individuals. Furthermore, non-BD individuals had larger P3 amplitudes in response to congruent stimuli than in response to incongruent stimuli, whereas the P3 amplitudes of BD individuals did not differ between congruent and incongruent stimuli. Taken together, these results indicate that BD individuals have deficits in memory updating and exert greater cognitive effort to perform working memory tasks as successfully as non-BD individuals.

Thus, the present study examined spatial working memory in BD college students using ERPs and a modified spatial n-back task. Based on previous findings, it was hypothesized that the BD and non-BD groups would not differ significantly in terms of behavioral performance on the spatial working memory task but that the two groups would exhibit different ERP patterns. Based on previous findings, we hypothesized that BD individuals would exhibit larger N2 amplitudes in response to congruent stimuli than non-BD individuals. In addition, BD individuals would exhibit no differences in P3 amplitudes in response to the three types of stimuli whereas non-BD individuals would exhibit larger P3 amplitudes in response to congruent stimuli than in response to incongruent or lure stimuli. To our knowledge, no studies have investigated spatial working memory in BD individuals using ERPs and a modified n-back task.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol consumption for 48 h prior to the experiment, and provided written informed consent after receiving a description of the study. The students were paid for their participation. This study was approved by the Sungshin Women’s University Institutional Review Board (SSWUIRB 2016–017).

Participants

The detailed procedures of the participant selection process have been described previously in a study by our research group [57]. The Korean version of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT-K, [58,59]), Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ, [60]) and a questionnaire containing items about alcohol use (e.g., frequency of BD episodes in the last 2 weeks and age of onset of alcohol use) were administered to 310 college students. For this study, BD was defined based on the quantity, frequency, and speed of alcohol consumption; either four (female) or five (male) drinks in a short period of time more than once during the previous 2 weeks [61,62] and either two (female) or three (male) drinks per hour [1].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a score > 8 on the AUDIT is recommended as the cut-off point for problem drinking [58]. However, others have suggested that the sensitivity and specificity for problem drinking are highest when an AUDIT score >12 is used as a cut-off [59,63]. An AUDIT score > 26 indicates the possibility of alcohol dependence [63].

In this study, those who obtained total scores of 12~26 on the AUDIT-K, had drunk four (female) or five (male) glasses more than once during the previous 2 weeks, and drank more than two (female) or three (male) glasses per hour were included in the BD group. Those who obtained total scores < 8 on the AUDIT-K, had drunk less than four (female) or five (male) glasses during the previous 2 weeks, and drank less than two (female) or three (male) glasses per hour were included in the non-BD group.

Because parental alcohol use can influence the alcohol use of their offspring [64], the Korean version of the Children of Alcoholics Screening Test (CAST-K, [65,66]) was administered to identify whether participants’ parents had a history of AUD; those who obtained a score > 6 on the CAST-K were excluded from the present study. To control for levels of intelligence, anxiety, and depression, the Korean Wechsler Intelligence Scale (KWIS, [67]), Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, [68]), and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS, [69]), respectively, were administered. Additionally, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Non Patient (SCID-NP, [70]) was administered to ensure that no participants had neurological, psychiatric disorders and drug/alcohol abuse.

Following the application of the initial inclusion and exclusion criteria, 46 students were placed in the BD group and 52 students were placed in the non-BD group. Subsequently, participants who were left handed, ambidextrous, had histories of neurological/ psychiatric disorders, or who refused to participate were also excluded from the study. Ultimately, there were 25 participants (8 males and 17 females) in both the BD (age range: 18–26 years) and non-BD (age range: 19–27 years) groups.

The modified spatial 2-back task

A modified spatial 2-back task was used to evaluate spatial working memory. This task included congruent, incongruent, and lure conditions; under the congruent condition, the locations of the current stimulus and the stimulus presented two trials earlier were the same; under the incongruent condition, the locations of the current stimulus and the stimulus presented two trials earlier were different; and under the lure condition, the stimulus presented one trial earlier was repeated. The stimulus, a red square, was presented in a 3 × 3 matrix and in total 360 trials (congruent, incongruent, and lure stimuli presented 108, 198, and 54 times, respectively) were administered in two blocks with the congruent, incongruent, and lure stimuli presented randomly. Participants were required to respond as accurately and quickly as possible in the congruent trials but not respond in the incongruent and lure trials.

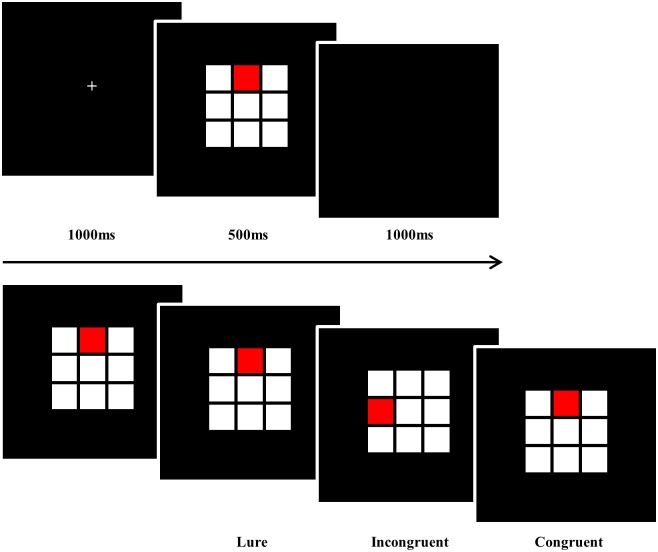

A crosshair was displayed for 1,000 ms and then the stimulus was presented for 500 ms followed by a 1,000 ms window for response time; there was an inter-stimulus interval of 2,500 ms. E-PRIME software (Psychological Software Tools Inc., Sharpsburg, PA, USA) was used for all operations and a block of 30 trials was administered prior to the experimental session to ensure that the participants understood the instructions. The three types of stimuli and the procedure for the stimulus presentation are illustrated in Fig 1.

Fig 1. The spatial 2-back task.

The spatial 2-back task consists of a congruent condition, under which the locations of the current stimulus and the stimulus presented 2 trials earlier are the same, incongruent condition, under which the locations of the current stimulus and the stimulus presented 2 trials earlier are different, and a lure condition, under which the stimulus presented one trial earlier is repeated. A crosshair was displayed for 1,000 ms and then the stimulus was presented for 500 ms followed by a 1,000 ms window for response time.

Electrophysiological recording procedure

Electrophysiological activity was assessed by electroencephalography (EEG) using a 64-channel Geodesic Sensor net connected to a 64-channel high-input impedance amplifier (Net Amp 300; Electrical Geodesics, Eugene, OR, USA) in a soundproof and electrically shielded experimental room. All electrodes were referenced to Cz and impedance was maintained at 50 kΩ or less [71]. Eye movements and blinks were monitored by electrodes positioned near the outer canthus and beneath the left eye.

All EEG activity was recorded continuously using a 0.01~400 Hz bandpass filter and a sampling rate of 500 Hz; collected EEG data were digitally filtered using a 0.3~30 Hz bandpass filter. Next, the EEG data from the congruent, incongruent, and lure conditions were segmented into 1,000 ms epochs (including a 100 ms pre-stimulus period) that were baseline-corrected. Epochs contaminated by artifacts were removed prior to averaging (based on a threshold of a peak-to-peak amplitude of ± 70 ㎶). Then all remaining data were averaged according to the congruent, incongruent, and lure conditions with an average-reference transformation.

The mean numbers of trials included in the congruent, incongruent, and lure conditions for the BD group were 76.68 (SD = 20.20), 156.32 (SD = 26.22), and 38.84 (SD = 7.90), respectively. The mean numbers of trials included in the congruent, incongruent, and lure conditions for the non-BD group were 77.12 (SD = 20.04), 157.00 (SD = 25.38), and 37.40 (SD = 10.71), respectively. The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of numbers of trials in the congruent (t(48) = .04, p = .94), incongruent (t(48) = .08, p = .97), or lure (t(48) = -.54, p = .59) conditions.

Statistical analysis

Demographic variables were analyzed with independent t-tests. The accuracy rate of the spatial 2-back task was analyzed with a repeated-measures mixed design analysis of variance (ANOVA) using condition as a within-subject factor (congruent, incongruent, and lure conditions) and group as a between-subject factor (BD and non-BD groups). Response time in the spatial 2-back task was assessed using independent t-tests.

The ERP components and their time windows were determined using the grand-averaged ERPs and individual ERP waveforms. N2 was defined as the most negative peak observed at from 170~340 ms after stimulus-onset; the amplitudes and latencies of N2 were analyzed with a mixed design ANOVA using condition and electrode site (F3, Fz, F4, FC3, FCz, FC4, C3, Cz, and C4) as within-subject factors and group as a between-subject factor. P3 was defined as the most positive peak from 250~550 ms after stimulus-onset; the amplitudes and latencies of P3 were analyzed with a mixed design ANOVA using condition and electrode site (F3, Fz, F4, FC3, FCz, FC4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, and P4) as within-subject factors and group as a between-subject factor. Green-Geisser corrections were used for violations of sphericity and the corrected p-values are reported when appropriate.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The BD and non-BD groups did not differ in terms of age (t(48) = .24, p = .34), educational level (t(48) = -.27, p = .29), IQ (t(48) = 1.22, p = .42), SDS (t(48) = -1.04, p = .69), state anxiety on the STAI (t(48) = -.94, p = .51), or trait anxiety on the STAI (t(48) = -1.78, p = .68). However, the BD group exhibited significantly higher AUDIT-K total score (t(48) = 18.75, p < .001), drinking speed (AUQ item 10) (t(48) = 11.13, p < .001), number of times being drunk in the previous 6 months (AUQ item 11) (t(48) = 6.26, p < .001) and percentage of times being drunk when drinking (AUQ item 12) (t(48) = 6.37, p < .001) compared to the non-BD group. The demographic characteristics of the BD and non-BD groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of non-binge drinking and binge drinking groups.

| Non-binge drinking (n = 25) |

Binge drinking (n = 25) |

t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 22.28 (2.44) |

22.12 (2.24) |

.24 |

| Education (years) | 14.92 (1.15) |

15.00 (.96) |

-.27 |

| IQ | 116.60 (8.80) |

113.84 (7.09) |

1.22 |

| SDS | 41.00 (6.79) |

42.92 (6.28 |

-1.04 |

| STAI state | 38.88 (11.46) |

46.03 (9.38) |

-.94 |

| STAI trait | 40.96 (7.64) |

45.08 (8.73) |

-1.78 |

| AUDIT-K | 1.64 (2.02) |

18.84 (4.12) |

-18.75 *** |

| Speed of drinking (drinks/hour) | .80 (.58) |

4.20 (1.41) |

-11.13 *** |

| Times drunk in the last 6 months | .20 (.58) |

8.36 (6.49) |

-6.26 *** |

| Percentage of times became drunk when drinking (%) | 10.00 (21.94) |

52.80 (25.42) |

-6.37*** |

| Age of starting drinking | 18.15 (.75) |

16.96 (1.61) |

-3.33** |

SDS, Self-Rating Depression Scale; STAI, Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; AUDIT-K, The Korean version of Alcohol Use Disorder Identify Test; AUQ, Alcohol Use Questionnaire.

***p < .001,

**p < .01

SD, standard deviation

Behavioral performance on the spatial 2-back task

In terms of accuracy rate, there was a significant main effect of condition (F(2,48) = 22.39, p < .001) such that the accuracy rates of the lure (p < .001) and congruent (p < .001) conditions were lower than that of the incongruent condition. There was no significant effect of group (F(1,48) = 3.56, p = .07) or a significant interaction effect of group × condition (F(2,96) = 1.90, p = .16). In terms of response time, the main effect of group (t(48) = 1.66, p = .10) was not significant. The mean accuracy rates and response times of the two groups on the spatial 2-back task are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Mean accuracy and response time in non-binge drinking and binge drinking groups.

| Non-binge drinking (n = 25) |

Binge drinking (n = 25) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lure | Incongruent | Congruent | Lure | Incongruent | Congruent | |

| Accuracy (%) | 93 | 99 | 94 | 92 | 99 | 90 |

| (.05) | (.01) | (.06) | (.07) | (.01) | (.11) | |

| Response time (ms) | 503.28 | 458.91 | ||||

| (92.65) | (95.92) | |||||

() standard deviation

Electrophysiological measures

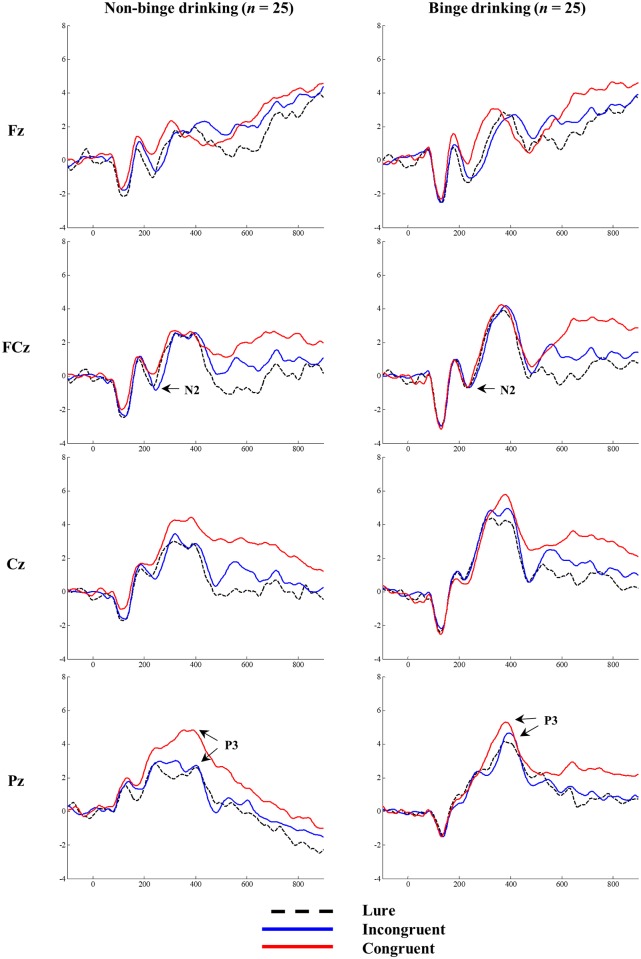

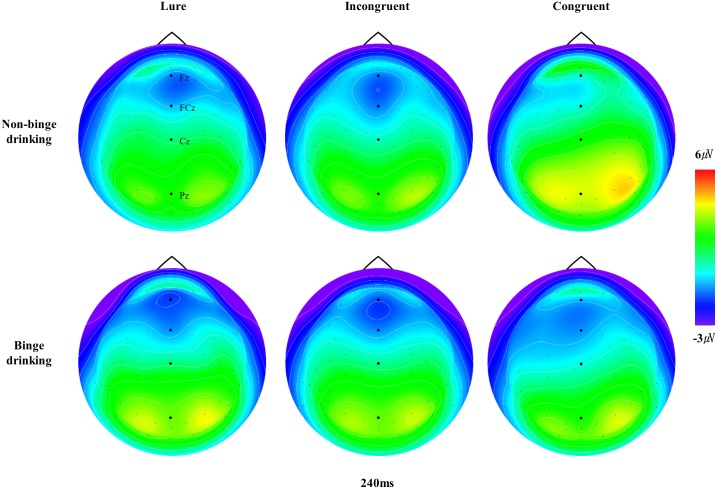

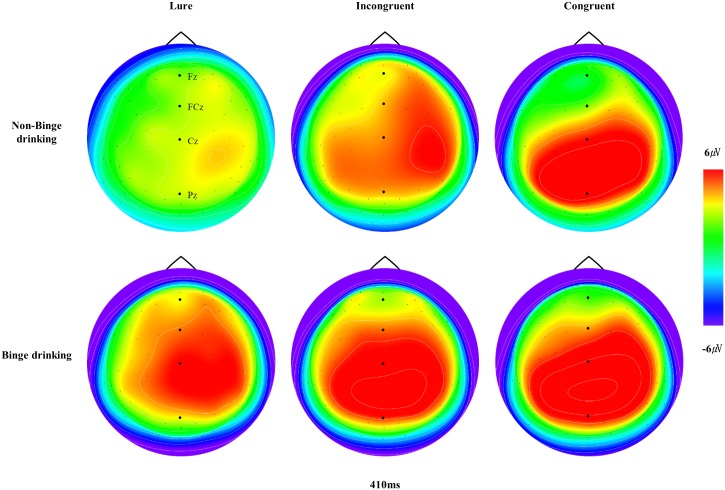

The grand-averaged ERPs elicited by the lure, incongruent, and congruent stimuli at the midline sites (Fz, FCz, Cz and Pz) for the BD and non-BD groups are displayed in Fig 2. The topographical distributions of N2 and P3 measured at all electrode sites when the maximum N2 and P3 amplitudes were observed are presented in Figs 3 and 4, respectively.

Fig 2. The grand-averaged ERPs.

The grand-averaged ERPs elicited by congruent, incongruent, and lure stimuli at Fz, FCz, Cz, and Pz for binge drinking and non-binge drinking groups.

Fig 3. The topographical distributions of N2.

The topographical distribution of N2 measured at all electrode sites when the maximum N2 amplitudes were observed.

Fig 4. The topographical distributions of P3.

The topographical distribution of P3 measured at all electrode sites when the maximum P3 amplitudes were observed.

Analyses of the N2 amplitudes revealed significant main effects of condition (F(2,96) = 7.57, p < .001) and electrode site (F(8,384) = 18.49, p < .001). The N2 amplitudes in response to the lure (p < .01) and incongruent (p < .01) stimuli were larger than those for congruent stimuli with the largest amplitude observed at Fz and the smallest observed at C4. There was also a significant interaction effect of condition × electrode site (F(16,768) = 4.48, p < .001). The N2 amplitudes elicited by the lure and incongruent stimuli were larger than those for congruent stimuli at Fz, F4, and FCz, whereas the N2 amplitudes elicited by the three types of stimuli did not differ at F3, FC3, FC4, C3, or C4. No significant main effect of group (F(1,48) = 1.11, p = .30) or interaction effects of group × condition (F(2,96) = 1.53, p = .22) and group × electrode site (F(8,384) = .28, p = .97) were observed.

In terms of N2 latency, there were significant main effects of condition (F(2,96) = 19.41, p < .001) and electrode site (F(8,384) = 6.24, p < .001). The N2 latencies elicited by the lure (p < .001) and congruent (p < .001) stimuli were significantly shorter than those elicited by incongruent stimuli and the shortest and longest N2 latencies were observed at C4 and F3, respectively. However, no significant main effect of group (F(1,48) = .30, p = .59) or interaction effects of group × condition (F(2,96) = .08, p = .92) and group × electrode site (F(8,384) = .78, p = .62) were observed. The mean N2 amplitudes and latencies for the BD and non-BD groups are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Mean N2 amplitudes and latencies in non-binge drinking and binge drinking groups.

| site | Non-binge drinking (n = 25) |

Binge drinking (n = 25) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lure | Incongruent | Congruent | Lure | Incongruent | Congruent | ||

|

Amplitude (μV) |

F3 | -0.99 | -1.34 | -0.57 | -1.83 | -1.79 | -1.39 |

| (1.97) | (2.09) | (2.17) | (2.13) | (1.83) | (1.90) | ||

| Fz | -2.17 | -1.40 | -0.63 | -2.64 | -2.18 | -1.02 | |

| (2.61) | (2.81) | (2.53) | (2.90) | (2.48) | (2.17) | ||

| F4 | -1.88 | -1.05 | -0.47 | -2.02 | -1.94 | -1.22 | |

| (3.06) | (1.92) | (2.03) | (2.18) | (2.39) | (2.15) | ||

| FC3 | -0.40 | -0.39 | -0.45 | -0.74 | -0.82 | -1.05 | |

| (1.56) | (1.30) | (1.67) | (1.54) | (1.60) | (1.58) | ||

| FCz | -1.92 | -1.66 | -0.77 | -2.04 | -1.91 | -1.46 | |

| (2.38) | (2.25) | (2.25) | (2.24) | (2.48) | (2.40) | ||

| FC4 | -0.79 | -0.31 | 0.04 | -0.32 | -0.79 | -0.45 | |

| (1.79) | (1.40) | (1.91) | (1.79) | (1.92) | (1.93) | ||

| C3 | -0.31 | 0.01 | 0.14 | -0.44 | -0.25 | -0.64 | |

| (1.82) | (1.22) | (1.59) | (1.49) | (1.12) | (1.47) | ||

| Cz | -0.66 | -0.39 | 0.49 | -0.53 | -0.45 | -0.50 | |

| (2.59) | (1.97) | (2.10) | (1.94) | (1.98) | (2.32) | ||

| C4 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.63 | 0.22 | -0.31 | 0.15 | |

| (1.95) | (1.49) | (2.07) | (1.45) | (1.13) | (1.37) | ||

|

Latency (ms) |

F3 | 242.96 | 251.12 | 237.60 | 240.32 | 246.08 | 230.32 |

| (33.35) | (36.51) | (33.85) | (25.49) | (34.87) | (30.64) | ||

| Fz | 225.92 | 242.96 | 226.32 | 230.72 | 248.00 | 228.48 | |

| (35.09) | (29.20) | (29.00) | (26.04) | (32.10) | (25.62) | ||

| F4 | 235.28 | 244.08 | 227.20 | 238.96 | 246.80 | 235.76 | |

| (38.53) | (39.19) | (29.10) | (30.98) | (36.09) | (24.99) | ||

| FC3 | 231.44 | 240.08 | 232.56 | 233.44 | 246.00 | 239.60 | |

| (30.87) | (33.72) | (45.83) | (27.76) | (31.53) | (23.44) | ||

| FCz | 229.60 | 242.96 | 234.08 | 237.60 | 250.24 | 233.44 | |

| (29.78) | (34.52) | (36.72) | (27.61) | (31.64) | (36.47) | ||

| FC4 | 225.20 | 230.24 | 227.44 | 235.44 | 239.36 | 232.96 | |

| (30.65) | (31.51) | (27.90) | (30.33) | (32.01) | (28.86) | ||

| C3 | 225.84 | 230.40 | 222.16 | 225.28 | 229.60 | 226.08 | |

| (38.50) | (38.76) | (30.04) | (30.15) | (35.11) | (25.07) | ||

| Cz | 233.12 | 239.04 | 226.72 | 229.44 | 234.80 | 224.96 | |

| (38.86) | (35.35) | (35.65) | (31.37) | (35.02) | (23.31) | ||

| C4 | 212.16 | 215.76 | 211.76 | 220.16 | 232.72 | 217.60 | |

| (29.30) | (31.62) | (35.76) | (30.88) | (39.26) | (30.44) | ||

() standard deviation

In terms of P3 amplitude, there was a significant main effect of group (F(1,48) = 7.04, p < .05) such that the BD group showed a larger P3 amplitude than the non-BD group. There was also a significant interaction effect of group × condition (F(2,96) = 4.24, p < .05). The non-BD group showed larger P3 amplitudes in response to the congruent stimuli than in response to the lure (p < .001) and incongruent (p < .001) stimuli whereas there was no significant difference in P3 amplitude in response to the three types of stimuli in the BD group (F(2,48) = 1.24, p = .30). There were also significant main effects of condition (F(2,96) = 12.84, p < .001) and electrode site (F(11,528) = 8.93, p < .001) such that larger P3 amplitudes were observed in response to the congruent stimuli than in response to the lure (p < .001) or incongruent (p < .05) stimuli. In terms of electrode site, the largest and smallest P3 amplitudes were observed at Pz and F3, respectively. There was a significant interaction effect of condition × electrode site (F(22,1056) = 5.62, p < .001) such that larger P3 amplitudes were observed in response to congruent stimuli than in response to lure and incongruent stimuli at Cz, C4, C3, Pz, P3 and P4. The P3 amplitudes elicited by the three types of stimuli did not differ at F3, Fz, F4, FC3, FCz, or FC4.

In terms of P3 latency, there was a significant main effect of condition (F(2,96) = 10.47, p < .001) with the longest P3 latency observed in response to the incongruent stimuli relative to the lure (p < .001) and congruent (p < .01) stimuli. However, no significant main effect of group (F(1,48) = .48, p = .49) or interaction effects of group × condition (F(2,96) = .66, p = .52) and group × electrode site (F(11,528) = 1.75, p = .08) were observed. The mean P3 amplitudes and latencies for the BD and non-BD groups are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Mean P3 amplitudes and latencies in non-binge drinking and binge drinking groups.

| site | Non-binge drinking (n = 25) |

Binge drinking (n = 25) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lure | Incongruent | Congruent | Lure | Incongruent | Congruent | ||

|

Amplitude (μV) |

F3 | 2.29 | 2.53 | 2.48 | 4.55 | 3.97 | 3.58 |

| (2.29) | (1.59) | (2.20) | (2.71) | (3.10) | (2.30) | ||

| Fz | 2.74 | 3.19 | 3.55 | 3.97 | 3.74 | 3.67 | |

| (2.53) | (2.37) | (2.71) | (2.84) | (2.81) | (2.29) | ||

| F4 | 3.37 | 3.24 | 3.68 | 4.50 | 3.92 | 4.04 | |

| (2.56) | (2.07) | (2.56) | (2.72) | (2.67) | (2.52) | ||

| FC3 | 2.05 | 2.65 | 3.01 | 4.25 | 4.60 | 4.38 | |

| (2.29) | (2.21) | (2.19) | (2.64) | (3.06) | (2.47) | ||

| FCz | 2.53 | 2.84 | 3.75 | 5.04 | 5.21 | 4.71 | |

| (2.49) | (2.26) | (2.50) | (3.24) | (3.63) | (3.07) | ||

| FC4 | 3.07 | 3.60 | 4.50 | 4.98 | 4.89 | 5.17 | |

| (2.50) | (2.59) | (2.76) | (2.40) | (2.61) | (2.59) | ||

| C3 | 2.54 | 3.12 | 3.69 | 3.99 | 4.62 | 4.70 | |

| (2.41) | (2.36) | (2.24) | (1.95) | (2.60) | (2.74) | ||

| Cz | 2.95 | 3.37 | 4.97 | 5.47 | 6.07 | 6.27 | |

| (2.19) | (2.12) | (2.38) | (2.56) | (2.99) | (3.14) | ||

| C4 | 3.57 | 3.79 | 4.97 | 5.12 | 5.23 | 5.68 | |

| (2.66) | (2.39) | (2.82) | (2.37) | (2.64) | (2.65) | ||

| P3 | 2.90 | 3.45 | 5.06 | 4.11 | 5.02 | 5.59 | |

| (1.70) | (2.46) | (2.68) | (1.64) | (2.06) | (2.28) | ||

| Pz | 3.79 | 3.70 | 5.72 | 4.52 | 5.91 | 6.26 | |

| (2.21) | (1.84) | (1.80) | (1.99) | (2.32) | (2.16) | ||

| P4 | 4.22 | 4.22 | 5.53 | 4.48 | 5.26 | 5.77 | |

| (2.42) | (2.27) | (2.81) | (1.79) | (1.93) | (1.96) | ||

|

Latency (ms) |

F3 | 372.16 | 371.76 | 372.48 | 358.00 | 376.40 | 362.88 |

| (50.67) | (53.65) | (51.21) | (35.39) | (36.66) | (43.26) | ||

| Fz | 355.52 | 366.16 | 365.04 | 390.40 | 404.00 | 377.20 | |

| (46.66) | (55.60) | (68.29) | (34.71) | (44.40) | (50.93) | ||

| F4 | 382.88 | 399.28 | 379.04 | 372.96 | 392.80 | 370.56 | |

| (42.67) | (41.56) | (43.60) | (34.51) | (39.56) | (50.39) | ||

| FC3 | 385.84 | 402.08 | 390.80 | 362.96 | 376.08 | 376.32 | |

| (46.06) | (37.42) | (40.79) | (36.47) | (45.41) | (43.37) | ||

| FCz | 376.88 | 398.24 | 383.20 | 378.16 | 389.76 | 379.44 | |

| (69.48) | (72.59) | (69.37) | (36.56) | (36.63) | (37.09) | ||

| FC4 | 390.64 | 394.56 | 387.44 | 376.88 | 385.12 | 363.12 | |

| (55.29) | (54.11) | (56.92) | (39.75) | (39.96) | (36.58) | ||

| C3 | 375.44 | 384.40 | 380.16 | 378.00 | 385.68 | 378.88 | |

| (43.74) | (44.24) | (50.72) | (36.03) | (33.53) | (25.64) | ||

| Cz | 384.08 | 388.32 | 381.92 | 362.56 | 371.04 | 363.44 | |

| (59.30) | (63.65) | (57.71) | (50.79) | (51.13) | (42.53) | ||

| C4 | 372.08 | 386.72 | 371.20 | 385.28 | 390.96 | 380.72 | |

| (37.46) | (35.84) | (35.50) | (30.66) | (36.92) | (24.65) | ||

| P3 | 379.76 | 390.08 | 386.48 | 383.60 | 380.88 | 378.96 | |

| (44.80) | (38.71) | (43.81) | (44.08) | (43.10) | (29.29) | ||

| Pz | 377.36 | 370.00 | 371.36 | 371.20 | 373.84 | 361.44 | |

| (39.15) | (38.28) | (39.89) | (51.28) | (52.23) | (43.60) | ||

| P4 | 385.92 | 387.36 | 380.16 | 388.72 | 380.80) | 370.96 | |

| (46.33) | (35.42) | (43.33) | (32.32) | (49.49) | (28.74) | ||

() standard deviation

Discussion

This study investigated spatial working memory in BD college students using ERPs and a modified spatial 2-back task. The BD and non-BD groups did not differ significantly in terms of response time or accuracy, which is consistent with some [34,35] but not all previous studies [32,72]. These inconsistencies seem to be the result of differences in the participants assessed in these studies. For example, previous studies that reported poor performance in BD individuals included older subjects [72] and subjects who had an earlier onset of alcohol consumption [32] compared to those who participated in this study. In other words, the emergence of behavioral deficits in the working memory task likely required a somewhat long period of BD.

In this study, both groups showed significantly lower accuracy rates and shorter response times in response to the lure and congruent stimuli than in response to the incongruent stimuli. These results indicate that the participants confused the lure stimuli as congruent stimuli which, in turn, resulted in more errors under the congruent and lure conditions than under the incongruent condition [29,30].

In terms of N2 amplitude, both the BD and non-BD groups exhibited larger N2 amplitudes in response to the incongruent and lure stimuli than in response to the congruent stimuli. These results are consistent with those of previous studies showing larger N2 amplitudes in response to incongruent stimuli than in response to congruent stimuli on the n-back task [27,29,73]. Additionally, both groups showed significantly shorter response times to congruent and lure stimuli than to incongruent ones, which indicate that the lure stimulus was misidentified as a congruent stimulus. N2 reflects the inhibition of inappropriate responses [29,43] as well as the process involved in detecting whether a current stimulus is the same as or different from one presented n trials earlier [42]. The present results (i.e., larger N2 amplitudes in response to incongruent and lure stimuli than in response to congruent stimuli and the longest N2 latency to incongruent stimuli) support these functional activities of N2. In other words, BD individuals maintain the ability to inhibit or detect inappropriate information.

On the other hand, the BD group had significantly larger P3 amplitudes than the non-BD group, and the amplitudes were larger in response to congruent stimuli than in response to incongruent or lure stimuli. Moreover, P3 latency was longer in response to incongruent stimuli than in response to congruent or lure stimuli. The functional significance of P3 amplitude in working memory tasks is not yet fully understood. Some authors have suggested that P3 amplitude reflects the process of classifying task-relevant stimuli [45] whereas others have suggested that it reflects the updating of current information in working memory [46,49,74]. In particular, Kim et al. [75] proposed that a larger P3 amplitude and shorter P3 latency in response to congruent stimuli than in response to incongruent stimuli on the n-back task is indicative of the updating of information or of the decision-making process. Still others have suggested that P3 reflects the capacity for attentional allocation [76]. Therefore, enhanced P3 amplitudes in BD individuals may represent enhanced cognitive effort towards the classification and updating of information or attentional allocation to information.

Neuroimaging studies support this interpretation. For example, Campanella et al. [36] measured brain activation in BD and non-BD subjects during the performance of a verbal working memory task and found increased bilateral activation in the pre-supplementary motor area in the BD group relative to the non-BD group despite comparable performances on the verbal working memory task by the two groups. Furthermore, Schweinsburg et al. [77] reported that BD and non-BD groups did not differ in terms of response time or accuracy on spatial working memory tasks but BD individuals exhibited significant increases in activation in the dorsal prefrontal and parietal cortices. These authors suggested that BD individuals maintain performance levels in spatial working memory tasks by increasing activation of brain areas involved in working memory.

In the present study, non-BD individuals showed larger P3 amplitudes in response to congruent stimuli than in response to incongruent and lure stimuli whereas the differences in P3 amplitudes between the congruent and incongruent or lure stimuli were not significant in individuals with BD. These results are consistent with those of previous studies. For example, Crego et al. [55] investigated visual working memory in BD college students and found that non-BD individuals exhibited larger P3 amplitudes in response to congruent stimuli than in response to incongruent stimuli whereas those with BD did not show significant differences in P3 amplitudes between congruent and incongruent stimuli. Taken together, the previous and present results indicate that BD individuals are less efficient in differentiating relevant and irrelevant stimuli and in allocating attentional resources between relevant and irrelevant information.

The present study has several limitations that should be addressed in future studies. First, only a small number of young adult participants was assessed, which limits the generalizability of the present findings. Second, BD individuals are more likely to use other substances, including cigarettes [78], so these substances should be controlled for in future studies. Third, there are significant sex differences in BD in terms of both behavior [32] and electrophysiology [79] and, therefore, future studies should examine whether male and female binge drinkers exhibit different behavioral performances and ERP patterns on working memory tasks. Finally, because the EEG has low spatial resolution in spite of its high temporal resolution, the generators of the N2/P3 could not be clearly identified. Therefore, to elucidate the neurophysiological mechanisms of spatial working memory deficits in BD individuals, neuroimaging techniques or source localization techniques with ERPs should be used in future studies.

In conclusion, the BD and non-BD groups assessed in this study did not differ in terms of response time or accuracy rate on the spatial 2-back task. However, the BD group exhibited significantly larger P3 amplitudes than the non-BD group and did not show any significant differences in P300 amplitudes among congruent, incongruent, and lure stimuli whereas the non-BD group showed larger P300 amplitudes in response to congruent stimuli than in response to incongruent or lure stimuli. Therefore, the present findings indicate that BD individuals exert greater effort when classifying and updating information or allocating attention to maintain comparable performance on a spatial working memory task relative to non-BD individuals. Furthermore, BD individuals were less efficient in differentiating and allocating attentional resources between relevant and irrelevant information. The results imply that investigations of working memory in BD individuals should employ electrophysiological or neuroimaging techniques as well as behavioral measurements because alteration in the neural network involved in working memory occur prior to the emergence of behavioral deficits. The present results also provide valuable information about the detrimental effects of BD on the neural systems involved in spatial working memory, even when the duration of BD is relatively short (mean months of alcohol consumption in the BD group was 30.92 months).

Supporting information

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2015S1A5A2A03047656). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA newsletter. 2004; 3(3). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balodis IM, Potenza MN, Olmstead MC. Binge drinking in undergraduates: relationships with gender, drinking behaviors, impulsivity and the perceived effects of alcohol. Behav Pharmacol. 2009; 20(5–6): 518–526. 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328330c779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003; 23(5): 719–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silveri MM. Adolescent brain development and underage drinking in the United States: identifying risks of alcohol use in college populations. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2012; 20(4): 189–200. 10.3109/10673229.2012.714642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courtney KE, Polich J. Binge drinking in young adults: data, definitions, and determinants. Psychol Bull. 2009; 135(1): 142–156. 10.1037/a0014414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wicki M, Kuntsche E, Gmel G. Drinking at European universities? a review of students’ alcohol use. Addict Behav. 2010; 35(11): 913–924. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennison KM. The short-term effects and unintended long-term consequences of binge drinking in college: a 10-year follow-up study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004; 30(3): 659–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cservenka A, Brumback T. The burden of binge and heavy drinking on the brain: effects on adolescent and young adult neural structure and function. Front Psychol. 2017; 8: 1111 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mota N, Parada M, Crego A, Doallo S, Caamaño-Isorna F, Rodríguez-Holguín S, et al. Binge drinking trajectory and neuropsychological functioning among university students: a longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013; 133(1): 108–114. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbia C, López-Caneda E, Corral M, Cadaveira F. A systematic review of neuropsychological studies involving young binge drinker. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018; 90: 332–349. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baddeley AD. The fractionation of working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996; 93(24): 13468–13472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baddeley AD, Hitch G. Working memory. Psychol Learning Motiv. 1974; 8: 47–89. 10.1016/s0079-7421(08)60452-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engle RW, Kane MJ, Tuholski SW. Individual differences in working memory capacity and what they tell us about controlled attention, general fluid intelligence, and functions of the prefronal cortex In: Miyake A, Shah P, editors. Models of working memory: mechanisms of active maintenance and executive control. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. p. 102–134. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mariani MA, Barkley RA. Neuropsychological and academic functioning in preschool boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Dev Neuropsychol. 1997; 13(1): 111–129. 10.1080/87565649709540671 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Constantinidis C, Wang XJ. A neural circuit basis for spatial working memory. Neuroscientist. 2004; 10(6): 553–565. 10.1177/1073858404268742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis CE. Prefrontal and parietal contributions to spatial working memory. Neuroscience. 2006; 139(1): 173–180. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courtney SM, Petit L, Maisog JM, Ungerleider LG, Haxby JV. An area specialized for spatial working memory in human frontal cortex. Science. 1998; 279(5355): 1347–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith EE, Jonides J. Neuroimaging analyses of human working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998; 95(20): 12061–12068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ambrose ML, Bowden SC, Whelan G. Working memory impairments in alcohol-dependent participants without clinical amnesia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001; 25(2): 185–191. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfefferbaum A, Desmond JE, Galloway C, Menon V, Glover GH, Sullivan EV. Reorganization of frontal systems used by alcoholics for spatial working memory: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2001; 14(1): 7–20. 10.1006/nimg.2001.0785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tapert SF, Brown GG, Kindermann SS, Cheung EH, Frank LR, Brown SA. fMRI measurement of brain dysfunction in alcohol-dependent young women. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001; 25(2): 236–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilcox CE, Dekonenko CJ, Mayer AR, Bogenschutz MP, Turner JA. Cognitive control in alcohol use disoder: deficits and clinical relevance. Rev Neurosci. 2014; 25(1): 1–24. 10.1515/revneuro-2013-0054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopera M, Wojnar M, Brower K, Glass J, Nowosad I, Gmaj B, et al. Cognitive functions in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol. 2012; 46(7): 665–671. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tapert SF, Brown SA. Neuropsychological correlates of adolescent substance abuse: four-year outcomes. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999; 5(6): 481–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schweinsburg AD, Schweinsburg BC, Cheung EH, Brown GG, Brown SA, Tapert SF. fMRI response to spatial working memory in adolescents with comorbid marijuana and alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005; 79(2): 201–210. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owen AM, McMillan KM, Laird AR, Bullmore E. N-back working memory paradigm: a meta-analysis of normative functional neuroimaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005; 25(1): 46–59. 10.1002/hbm.20131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watter S, Geffen GM, Geffen LB. The n-back as a dual-task: P300 morphology under divided attention. Psychophysiology. 2001; 38(6): 998–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitel AL, Witkowski T, Vabret F, Guillery-Girard B, Desgranges B, Eustache F, et al. Effect of episodic and working memory impairments on semantic and cognitive procedural learning at alcohol treatment entry. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007; 31(2): 238–248. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00301.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stroux D, Shushakova A, Geburek-Höfer A, Ohrmann P, Rist F, Pedersen A. Deficient interference control during working memory updating in adults with ADHD: an event-related potential study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016; 127(1): 452–463. 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szmalec A, Verbruggen F, Vandierendonck A, Kemps E. Control of interference during working memory updating. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2011; 37(1): 137–151. 10.1037/a0020365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgess GC, Gray JR, Conway AR, Braver TS. Neural mechanisms of interference control underlie the relationship between fluid intelligence and working memory span. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2011; 140(4): 674–692. 10.1037/a0024695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Townshend JM, Duka T. Binge drinking, cognitive performance and mood in a population of young social drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005; 29(3): 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scaife JC, Duka T. Behavioural measures of frontal lobe function in a population of young social drinkers with binge drinking pattern. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009; 93(3): 354–362. 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartley DE, Elsabagh S, File SE. Binge drinking and sex: effects on mood and cognitive function in healthy young volunteers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004; 78(3): 611–619. 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parada M, Corral M, Mota N, Crego A, Rodríguez-Holguín S, Cadaveira F. Executive functioning and alcohol binge drinking in university students. Addict Behav. 2012; 37(2): 167–172. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campanella S, Peigneux P, Petit G, Lallemand F, Saeremans M, Noël X, et al. Increased cortical activity in binge drinkers during working memory task: a preliminary assessment through a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. PLoS One. 2013; 8(4): e62260 10.1371/journal.pone.0062260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schweinsburg AD, McQueeny T, Nagel BJ, Eyler LT, Tapert SF. A preliminary study of functional magnetic resonance imaging response during verbal encoding among adolescent binge drinkers. Alcohol. 2010; 44(1): 111–117. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.09.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Squeglia LM, Schweinsburg AD, Pulido C, Tapert SF. Adolescent binge drinking linked to abnormal spatial working memory brain activation: differential gender effects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011; 35(10): 1831–1841. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01527.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luck SJ. An introduction to the event-related potential technique. Massachusettes, MA: MIT press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hillyard SA, Kutas M. Electrophysiology of cognitive processing. Annu Rev Psychol. 1983; 34(1): 33–61. 10.1146/annurev.ps.34.020183.000341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen YN, Mitra S. The spatial-verbal difference in the n-back task: an ERP study. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2009; 18(3): 170–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daffner KR, Chong H, Sun X, Tarbi EC, Riis JL, McGinnis SM, et al. Mechanisms underlying age-and performance-related differences in working memory. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011: 23(6); 1298–1314. 10.1162/jocn.2010.21540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Folstein JR, Van Petten C. Influence of cognitive control and mismatch on the N2 component of the ERP: a review. Psychophysiology. 2008; 45(1): 152–170. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00602.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel SH, Azzam PN. Characterization of N200 and P300: selected studies of the event-related potential. Int J Med Sci. 2005; 2(4): 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kok A. On the utility of P3 amplitude as a measure of processing capacity. Psychophysiology. 2001; 38(3): 557–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saliasi E, Geerligs L, Lorist MM, Maurits NM. The relationship between P3 amplitude and working memory performance differs in young and older adults. PLoS One. 2013; 8(5): e63701 10.1371/journal.pone.0063701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McEvoy LK, Smith ME, Gevins A. Dynamic cortical networks of verbal and spatial working memory: effects of memory load and task practice. Cereb Cortex. 1998; 8(7): 563–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeon YW, Polich J. Meta-analysis of P300 and schizophrenia: patients, paradigms, and practical implications. Psychophysiology. 2003; 40(5): 684–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donchin E, Coles MGH. Is the P300 component a manifestation of context updating? Behav Brain Sci. 1988; 11(3): 357–374. 10.1017/s0140525x00058027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nieuwenhuis S, Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. Decision making, the P3, and the locus coeruleus—norepinephrine system. Psychol Bull. 2005; 131(4): 510–532. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polich J, Kok A. Cognitive and biological determinants of P300: an integrative review. Biol Psychol. 1995; 41(2): 103–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.George MR, Potts G, Kothman D, Martin L, Mukundan CR. Frontal deficits in alcoholism: an ERP study. Brain Cogn. 2004; 54(3): 245–247. 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang X L, Begleiter H, Porjesz B. Is working memory intact in alcoholics? an ERP study. Psychiatry Res. 1997; 75(2): 75–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crego A, Cadaveira F, Parada M, Corral M, Caamaño-Isorna F, Holguín SR. Increased amplitude of P3 event-related potential in young binge drinkers. Alcohol. 2012; 46(5): 415–425. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crego A, Rodriguez-Holguín S, Parada M, Mota N, Corral M, Cadaveira F. Binge drinking affects attentional and visual working memory processing in young university students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009; 33(11): 1870–1879. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.López-Caneda E, Cadaveira F, Crego A, Doallo S, Corral M, Gómez-Suárez A, et al. Effects of a persistent binge drinking pattern of alcohol consumption in young people: a follow-up study using event-related potentials. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013; 48(4): 464–471. 10.1093/alcalc/agt046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoo JY, Kim MS. Deficits in decision-making and reversal learning in college students who participate in binge drinking. Neuropsychiatry. 2016; 6(6): 321–330. 10.4172/neuropsychiatry.1000156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee BO, Lee CH, Lee PG, Choi MJ, Namkoong K. Development of Korean version of alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT-K): its reliability and validity. J Korean Acad Addict Psychiatry. 2000; 4(2): 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mehrabian A, Russell JA. A questionnaire measure of habitual alcohol use. Psychol Rep. 1978; 43(3): 803–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wechsler H, Isaac N. Binge drinkers at Massachusetts colleges: prevalence, drinking style, time trends, and associated problems. JAMA. 1992; 267(21): 2929–2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wechsler H, Nelson TF. Binge drinking and the American college students: what’ s five drinks? Psychol Addict Behav. 2001; 15(4): 287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim JS, Oh MK, Park BK, Lee MK, Kim G J. Screening criteria of alcoholism by alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in Korea. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 1999; 20(9): 1152–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ary DV, Tildesley E, Hops H, Andrews J. The influence of parent, sibling, and peer modeling and attitude on adolescent use of alcohol. Int J Addict. 1993; 28(9): 953–880. 10.3109/10826089309039661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim MR, Chang HI, Kim KB. Development of the Korean version of the children of alcoholics screening test (CAST-K): a reliability and validity study. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Association. 1995; 34(4): 1182–1193. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones JW. The children of alcoholics screening test: test manual. Chicago: Camelot Unlimited; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yum TH, Park YS, Oh KJ, Kim JG, Lee YH. The manual of Korean-Wechsler adult intelligence scale. Seoul: Korean Guidance Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965; 12(1): 63–70. 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I Disorders—Research version. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tucker DM. Spatial sampling of head electrical fields: the geodesic sensor net. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993; 87(3): 154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weissenborn R, Duka T. Acute alcohol effects on cognitive function in social drinkers: their relationship to drinking habits. Psychopharmacology. 2003; 165(3): 306–312. 10.1007/s00213-002-1281-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim S, Kim MS. Deficits in verbal working memory among college students with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder traits: an event-related potential study. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2016; 14(1): 64–73. 10.9758/cpn.2016.14.1.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao X, Zhou R, Fu L. Working memory updating function training influenced brain activity. PLoS One. 2013; 8(8): e71063 10.1371/journal.pone.0071063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim MS, Kwon JS, Kim JJ. The neurophysiological mechanism of working memory: an event-related potential study. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2004; 23(2): 313–326. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Polich J. Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007; 118(10): 2128–2148. 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schweinsburg AD, Schweinsburg BC, Nagel BJ, Eyler LT, Tapert SF. Neural correlates of verbal learning in adolescent alcohol and marijuana users. Addiction. 2011; 106(3): 564–573. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03197.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McKee SA, Hinson R, Rounsaville D, Petrelli P. Survey of subjective effects of smoking while drinking among college students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004; 6(1): 111–117. 10.1080/14622200310001656939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith JL, Mattick RP, Sufani C. Female but not male young heavy drinkers display altered performance monitoring. Psychiatry Res. 2015; 233(3): 424–435. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its supporting information files.