Abstract

Objective

Cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) improves adaptation to primary treatment for breast cancer (BCa), evidenced as reductions in distress and increases in positive affect. Because not all BCa patients may need psychosocial intervention, identifying those most likely to benefit is important. A secondary analysis of a previous randomized trial tested whether baseline level of cancer-specific distress moderated CBSM effects on adaptation over 12 months. We hypothesized that patients experiencing the greatest cancer-specific distress in the weeks after surgery would show the greatest CBSM-related effects on distress and affect.

Methods

Stages 0–III BCa patients (N = 240) were enrolled 2–8 weeks after surgery and randomized to either a 10-week group CBSM intervention or a 1-day psychoeducational (PE) control group. They completed the Impact of Event Scale (IES) and Affect Balance Scale (ABS) at study entry, and at 6- and 12- month follow-ups.

Results

Latent Growth Curve Modeling across the 12-month interval showed that CBSM interacted with initial cancer-related distress to influence distress and affect. Follow-up analyses showed that those with higher initial distress were significantly improved by CBSM compared to control treatment. No differential improvement in affect or intrusive thoughts occurred among low-distress women.

Conclusion

CBSM decreased negative affect and intrusive thoughts and increases positive affect among post-surgical BCa patients presenting with elevated cancer-specific distress after surgery, but did not show similar effects in women with low levels of cancer-specific distress. Identifying patients most in need of intervention in the period after surgery may optimize cost-effective cancer care.

Keywords: Cognitive-behavioral stress management, Cancer-specific distress, Intrusive thoughts, Negative and Positive affect, Breast cancer

A cancer diagnosis induces a serious crisis in the lives of patients, and leads to confrontation of one’s mortality [1]. Despite good prognosis at early stages, breast cancer (BCa) remains a distressing diagnosis. Multiple studies have assessed the effectiveness of psychological interventions on patients’ psychological adaptation. Group-based cognitive-behavior stress management intervention (CBSM) has been designed to facilitate adaptation during and after BCa treatment [2] and evidence supports its favorable effects on mood and other indicators of adaptation [2–4].

Although CBSM has shown to be efficacious for BCa patients, studies have commonly reported results based on samples regardless of their initial distress level. Although facing BCa diagnosis and treatments are generally distressing, there is substantial heterogeneity in the level of perceived cancer stress after BCa diagnosis [5]. It has been postulated that cancer patients with elevated distress have greater benefits from psychosocial interventions [6], but moderator analyses of BCa intervention effects have shown mixed results. One study found greater reduction in stress and anxiety for women reporting greater baseline levels of stress[7]. However, another study showed that the intervention was equally effective in reducing anxiety regardless of levels of baseline BCa-related stress [8]. It’s possible the mixed findings were due to differences in intervention type and length, as well as phase in cancer trajectory. This has not been tested for CBSM, which specifically targeting post-surgery BCa patients. It is desirable to test whether subgroups of BCa patients presenting with elevated cancer-specific distress might benefit most from approaches such as CBSM, as approaches in treating cancer distress are moving to a stepped-care approach[9].

Cancer-related thought intrusions about the diagnosis and its treatment have been used as an indicator of cancer-specific distress in BCa [10–12]. Prior to and during adjuvant therapy, such distress may emanate from commonly observed concerns about being physically damaged from the treatment and fears of cancer recurrence or death [13]. Intrusive thoughts about these adversities are common [14] and can compromise patients’ emotional well-being by continuously and recurrently generating cancer-related reminders [11]. Thus it is plausible that patients experiencing elevated intrusive thoughts might benefit the most from psychosocial interventions such as CBSM, which specifically targets intrusive thoughts through skills such asrelaxation, cognitive restructuring, and coping skills training, to build awareness, reduce tension and modify cognitive appraisals [15].

This study is a secondary analysis of a previous trial, which showed that CBSM affected negative and positive affect among BCa patients. This secondary analysis tests whether these effects on are moderated by initial level of cancer-specific distress (i.e., cancer-related intrusive thoughts). We also explored whether the effectiveness of CBSM on reducing frequency of intrusive thoughts was greater among patients with initially higher cancer-specific distress. We hypothesized that women presenting with greater distress in the period after surgery would receive the greatest benefit from CBSM intervention over a 12-month follow-up period encompassing primary BCa treatment.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 240 women (aged 18–75 years old) with stage 0 – IIIb BCa, recruited from South Florida cancer treatment centers between 1998 – 2005. Women with new primary BCa diagnosis and treated with surgery within the past 2 to 8 weeks were included. Exclusion criteria were (1) a history of prior cancer or neo-adjuvant treatment, (2) having already initiated adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation treatment, (3) severe psychiatric illness, (4) acute or chronic comorbid medical conditions, (5) not being fluent in English, and (6) unwillingness to be randomized to study conditions. The study was approved by the institutional review board (University of Miami, Coral Gables IRB# 93/536), and all participants provided written informed consent. For full details see prior reports on the parent trial [16].

Initial assessments were completed prior to randomization (T1). Follow-ups were completed at approximately 6-months (T2) and 12-months (T3) after study entry. Following data collection at T1, participants were randomized to a 10-week CBSM intervention or 1-day psychoeducation (PE) control seminar. There were no differences between those assigned to CBSM or PE in age, education, income, ethnicity, marital/partner status, cancer stage, surgical procedure, chemotherapy receipt, radiation therapy receipt, or any of the study outcome variables (p > .05). Participants were randomized to one of two conditions using a computer program.

CBSM: Intervention Condition

The CBSM intervention was a manualized 10-week group intervention targeting the needs of women under treatment for BCa [15]. The CBSM intervention aimed at ameliorating cancer- and treatment-related stress by teaching women to cope effectively and optimize the use of social resources. This intervention comprised cognitive restructuring, coping effectiveness training, interpersonal skills training (assertiveness, anger management, ways to enhance social support receipt), and relaxation training (muscle relaxation, deep breathing, relaxing imagery, meditation)[15]. The intervention addressed these topics through weekly didactic presentations, and in-session demonstration exercises as well as through at-home practice. Over the course of ten weeks, groups of 3 – 9 BCa patients met weekly for 2 hours led by pairs of pre-doctoral and post-doctoral female interventionists, supervised by clinical psychologists via videotaped sessions and weekly face-to-face meetings.

PE: Control Condition

A 1-day, 5–6 hour psychoeducational (PE) group seminar served as the control condition, and occurred midway through the 10-week CBSM intervention period for each cohort. Women were given cancer-related health information and condensed educational information about stress management techniques. PE was designed as a self-help seminar, so women did not have the opportunities to practice those techniques in the group and had minimal experience in a supportive group environment.

Measures

Cancer-Specific Distress

The baseline (T1) Intrusion subscale scores on the Impact of Event Scale [IES; 17] served as the measure of cancer-specific distress. In this study, the IES was anchored to the extent to which one experiences unwanted thoughts and images related to the experience of diagnosis of and treatment for BCa. The intrusion subscale (7 items) measures intrusive symptoms (intrusive thoughts, nightmares, anxiety and imagery). Respondents were asked to rate the items on a 4-point scale according to how often each of these experiences occurred in the past week as follows: 0 (not at all), 1 (rarely), 3 (sometimes), and 5 (often). Alpha for this subscale in the present study averaged .86 across time points.

Affect

The Affects Balance Scale [ABS; 18] was used to measure positive and negative affect. The ABS items include a set of adjectives assessing aspects of positive (i.e., affection, contentment, vigor, and joy) and negative moods (i.e., depression, hostility, guilt, and anxiety) separately. Respondents indicate the degree to which [from never (0) to always (4) on a 5-point Likert scale] they have experienced each of the negative (20 items) and positive (20 items) emotional states during “the past week including today.” The average alpha was .93 and .95, for negative and positive affect, respectively, across the study time points.

Statistical Analysis

To test whether women with greater cancer-specific distress at baseline demonstrate greater CBSM effects, latent growth-curve modeling (LGM) was carried out separately for each of the three outcome measures (i.e., negative affect, positive affect, and intrusive thoughts). LGM uses all available data, estimated by a full information maximum likelihood method, so all participants are represented in the intent-to-treat approach. LGM depicts repeated measures as a growth parameter with inter-individual differences. The LGM models were assessed with the Lisrel 8.7 program [19]. The data collected at T1, T2, and T3 were modeled as trajectories of change (characterized by an intercept and slope) for each participant. Differences among persons in the intercept and slope were predicted from intervention conditions (CBSM coded as 1, PE coded as 0), baseline cancer-specific distress, and the interaction of cancer-specific distress with condition. The intercept represents individual levels of positive/negative affect or intrusive thoughts at baseline. The slope represents the trend of each individual’s growth curve. A linear model was assumed, so loadings for the slope were coded as months elapsed until the assessment (0 for baseline, 6 for T2, and 12 for T3). Model fit indices were determined and modifications were made as needed. However, the original plan did not fit the data of all three outcomes. When T3 was freely estimated (i.e., 0 for baseline, 6 for T2, and free estimation for T3), the resulting overall model fit the data well. This suggested that changes in the outcomes from T1 to T2 and T2 to T3 did not happen at the same rate. Estimations of T3 were reported for each outcome.

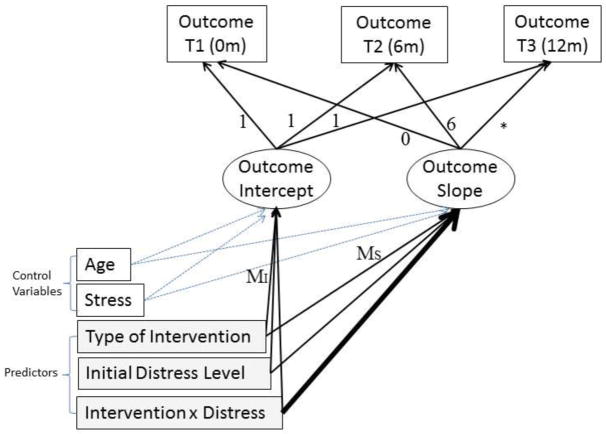

The structure of this model is depicted in Figure 1. In each LGM model, predictors were intervention condition, baseline cancer-specific distress level, and their interaction. Previous studies found CBSM intervention effects in the present cohort [3, 20]. Here we explored whether baseline distress level moderates intervention effects. Thus, the primary result of interest was the interaction between intervention condition and baseline distress.. Previous studies have indicated no condition (CBSM vs PE) difference at baseline (MI) in the parent trial [3, 20], so we focused on paths from the interaction term to the slope (MS). A significant effect indicates a difference in intervention effect as a function of baseline distress level. Control variables were chosen based on prior studies [3, 20], in which age and concurrent stress unrelated to cancer emerged as correlates of affect and intrusive thoughts.

Figure 1.

Structural Model for Effects of Intervention Condition and High and Low Cancer- Specific Distress Groups. MI reflects the extent to which group difference in initial values relates to the predictors. MS reflects the extent to which change in the outcome variable over time relates to the predictors. An asterisk indicates the loading was freely estimated. The solid bold arrow indicates the test for moderation, the key interest of this study. Stress = concurrent stress unrelated to cancer; Distress = baseline cancer-specific distress; Intervention = intervention conditions (CBSM coded as 1, PE coded as 0); CBSM = Cognitive-behavioral stress management; PE = psychoeducational control condition; T = Time; m=months.

Following Hu and Bentler [21] several indicators of model fit were used to assess the congruence between the data and the tested model. These include the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), for which values above 0.95 indicate good fit, as well as the Standardized Root-Mean-Square Residual (SRMR) and the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), for which values below 0.10 indicate good fit [22]. Specific effects were tested with the z statistic. Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d, for which values of 0.20 are regarded as relatively small, 0.50 as medium, and 0.80 as large effects [23].

If the path from interaction to slope was significant, we proceeded to compare the intervention effect among high vs. low distress women by an IES-intrusion median split. This depicts how CBSM effects on the change of the outcomes differ between women with high and low baseline distress. Four groups thus were created (high-distress/CBSM, high-distress/PE, low-distress/CBSM, low-distress/PE), using three dummy coded variables. We then ran the LGM models with these four groups as predictors, comparing group difference in their change. We hypothesized that the comparison between high-distress/CBSM vs. high-distress/PE would be significant, but low-distress/CBSM vs. low-distress/PE would be non-significant, indicating a difference in CBSM effects as a function of initial distress level.

Results

Five hundred and two women were screened for study participation but 262 were excluded or withdrew prior to randomization. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram shows study enrollment and retention (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Sample Demographics

Mean age was 50.9 years (SD=8.6, range=23–69). The majority of women were employed (76.0%) and most women were married (62.3%). Average years of education was 15.5 (SD=2.6). Median annual household income was $60,000 per year. More than half of the participants self-identified as Non-Hispanic White (66%); the remainder included Hispanic (22%), Black/African-American (10%) and Asian (2%). The sample included women diagnosed with breast cancer stage 0 (19%), stage I (37%), stage II (38%), and stage III (6%). Participants completed the first assessment on average 39.7 days (SD=23.3) post-surgery. About half (52.0%) had lumpectomies, 48% had mastectomies, and 31.4% received reconstructive surgery. Fifty-six percent of patients received chemotherapy, 57.7% radiation, and 69.7% hormone therapy over the study period. Table 1 presents demographic and medical characteristics by the study condition. There were no significant differences between CBSM and PE groups on any variables at baseline.

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics by the study condition

| Variables | PE control | CBSM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | p for difference | |

| Age at diagnosis [mean (SD)] | 50.99 (9.06) | 49.69 (8.98) | .26 |

| Race/ethnicity | .58 | ||

| White | 74 (62 %) | 78 (65 %) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 31 (26 %) | 30 (25 %) | |

| African American | 10 (8 %) | 11 (9 %) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (3 %) | 1 (1 %) | |

| Years of education | 15.47 (2.26) | 15.69 (2.50) | .47 |

| Married/Partnered | 75 (62 %) | 75 (62 %) | > .99 |

| Cancer stage | .40 | ||

| Stage 0 | 19 (16 %) | 19 (16 %) | |

| Stage I | 51 (43 %) | 39 (33 %) | |

| Stage II | 41 (34 %) | 50 (42 %) | |

| Stage III | 8 (7 %) | 11 (9 %) | |

| Surgery | .07 | ||

| Lumpectomy | 68 (57 %) | 54 (45 %) | |

| Mastectomy | 52 (43 %) | 66 (55 %) | |

| Treatment | |||

| Radiation | 60 (54 %) | 58 (54 %) | .98 |

| Chemotherapy | 56 (50 %) | 62 (57 %) | .27 |

| Tamoxifen/anti-hormone therapy | 71(63 %) | 74(68 %) | .42 |

| Reconstructive surgery | 40 (33 %) | 45 (38 %) | .50 |

Note: CBSM = Cognitive-behavioral stress management; PE = psychoeducational control condition.

Primary Analyses

Negative affect

The overall model fit the data well (χ2 (5) = 1.12, p = .34, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .02, SRMR = .03). T3 was estimated at 6.57 months after T1, indicating a plateauing from T2 to T3. Paths from baseline distress to intercept (z = 4.29, p < .001) and from the interaction term to slope (z = −2.05, p = .04; Cohen’s d = 0.32) were significant. The former indicated that baseline distress was positively correlated with baseline negative affect. The latter, test for interaction, indicated that baseline distress significantly moderated the intervention effect on negative affect over time.

To gain an understanding of the moderation effect, we dichotomized the sample on cancer-related distress (as described earlier), and then compared high-distress/CBSM with high-distress/PE and (separately) low-distress/CBSM with low-distress/PE. Contrasting the high-distress/CBSM with high-distress/PE group showed a significant relation of distress group to slope (z = −3.04, p = .002; Cohen’s d = 0.42), indicating differential change over time. For women with high baseline distress, those who received CBSM had reduced negative affect over time (z = −2.98, p = .003), whereas controls had no significant decline (z = −1.58, p = .11). We tested group differences at T2 and T3 by centering the intercept at those time points and recomputing the model, testing for condition effects on the intercept. We found significant condition effects on the intercept at T2 (z = −2.38, p = .02; d = 0.22) and T3 (z = −2.85, p = .004; d = 0.18), with CBSM showing lower negative affect vs PE at each point. Contrasting the low-distress/CBSM with low-distress/PE did not yield a group effect on slope (z = 0.52, p = .60), indicating no difference in change over time between the two low distress conditions. Figure 3 presents averaged negative affect across time by groups.

Figure 3.

Differential Effects of CBSM for Negative Affect and Positive Affect by Levels of Distress. Findings of a. and c. indicated significant differential change in two conditions. Findings of b. and d. indicated non-differential change in two conditions. CBSM = Cognitive-behavioral stress management; PE = psychoeducational control condition.

Positive affect

The overall model fit the data well (χ2 (5) = 1.17, p = .324, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .02). T3 was estimated at 7.67 months after T1, again suggesting a plateau across the second time span. Paths from intervention condition to slope (z = 2.50, p = .012) and from the interaction term to slope (z = 2.59, p = .01; Cohen’s d = 0.44) were significant. The former indicated significant difference in slopes between CBSM and PE. The latter, test for interaction, indicated that baseline distress level significantly moderated the intervention effect on positive affect.

Contrasts were conducted as described above. Contrasting high-distress/CBSM with high-distress/PE yielded a significant relation of group to slope (z = 2.59, p = .01; Cohen’s d = 0.44), indicating significant differential change over time. For women with high baseline distress, those who received CBSM had increased positive affect over time (z = 3.94, p < .001), while controls increased significantly but to a lesser extent (z = 2.01, p = .04). With the intercept centered at T2 and T3, the group differences were not significant (zs = 0.34 and 1.38). Thus, although the groups changed at different rates, the difference in levels of positive affect at both follow-ups was not itself significant. Contrasting low-distress/CBSM with low-distress/PE did not yield a significant effect on slope (z = −0.56, p = .58), indicating no differential change over time between groups. Figure 3 presents averaged positive affect across time by groups.

Intrusive thoughts

The overall model fit the data well (χ2 (6) = 0.42, p = .91, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, SRMR = .03). T3 was estimated at 6.33 months after T1, indicating relatively little change after T2. In this model, the path from baseline distress to intercept was fixed at value 1, as they were the same variable. Paths from intervention condition to slope (z = −3.74, p < .001), from baseline distress to slope (z = −8.06, p < .001), and from the interaction term to slope (z = −3.19, p = .001; Cohen’s d = 0.48) were all significant. The first indicated that baseline distress (i.e., baseline intrusive thoughts) was significantly associated with the slope of intrusive thoughts over time. The second indicated significant difference in slopes between CBSM and PE. The last, test for interaction, indicated that baseline distress level significantly moderated intervention effect on intrusive thoughts.

We then compared high-distress/CBSM with high-distress/PE and (separately) low-distress/CBSM with low-distress/PE. Within the high distress subsample, intervention condition related significantly to slope (z = −4.07, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.64), indicating substantial differential change over time. For women with high baseline distress, those who received CBSM had reduced intrusive thoughts over time (z = −4.55, p < .001), as well as controls (z = −2.68, p = .007). Comparing intercepts at T2 and T3 showed that conditions differed significantly at T2 (z = −3.69, p < .001; d = 0.43), and T3 (z = −3.79, p < .001; d = 0.46) such that the CBSM group had lower distress than did PE at each point. Condition was not related significantly to slope in the low distress group (z = −0.99, p = .32), indicating no differential change over time between groups. Figure 4 presents averaged intrusive thoughts across time by groups.

Figure 4.

Differential Effects of CBSM for Intrusive Thoughts by Levels of Distress. Findings of a. indicated significant differential change in two conditions. Findings of b. indicated non-differential change in two conditions. CBSM = Cognitive-behavioral stress management; PE = psychoeducational control condition.

Discussion

The purpose of this secondary analysis was to determine whether the effects of CBSM on psychological adaptation among BCa patients were greater for women reporting greater cancer-specific distress in the weeks after surgery. The results support that hypothesis. Among women with higher initial cancer-specific distress (measured as cancer-related intrusive thoughts), those randomized to the CBSM condition showed improvements (decreased negative affect and intrusive thoughts and increased positive affect) over 12 months compared to those in a PE control condition. There were no differential intervention effects on women who presented with low levels of cancer-specific distress.

These findings are consistent with studies showing that psychosocial intervention effects in cancer patients vary as a function of baseline levels of distress [7, 8, 24, 25]. Why is CBSM effective primarily for women with elevated cancer-specific distress at study entry? The simplest answer is that women who present with lower distress have less room for improvement. Although many patients show elevated levels of distress after diagnosis and surgery for BCa, there was a subset who experienced either little distress or a quick recovery after transient distress [26, 27]. A possible explanation is that these women do not experience the cancer diagnosis as a crisis [27]. Without the need and motive to change, intervening with these women may have little impact on their psychological adaptation.

High levels of cancer-related thought intrusions may indicate that patients are actively cognitive processing their experiences due to a disturbance in their basic assumptions about themselves and the world [28]. Intrusion is a sign of unresolved and incompatible information yet to be integrated within the patient’s belief system [28] and that the woman is struggling to make sense of the cancer experience [29]. Cognitive behavior therapy [30, 31] and Stress Inoculation Training [32] have been established to be effective for patients with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (e.g., thought intrusions). It is possible that CBSM empowers the patients with such challenges in dealing with unresolved thoughts, which results in improved affective experiences. Several components of CBSM have potential to do so; these techniques include increasing awareness of one's stress level, positive reframing, matching coping strategies to controllable and uncontrollable situations (via coping effectiveness training), encouraging emotional expression, and managing interpersonal conflicts (through assertiveness and anger management).

For example, encouraging emotional expression helps patients become aware of and process threatened beliefs about their well-being and safety because of the uncertain prognosis. Cognitive restructuring and reinterpretation help integrate or reconstruct the assumptive world [15]. In addition, relaxation skills reduce physical tension and arousal to cancer-related stress, which could in turn facilitate cognitive integration. Successful processing may lead to less negative affect and greater positive affect and should be accompanied by reductions in intrusive thoughts as was found in the present study.

Moreover, CBSM encourages utilization of effective social support and provides a supportive group environment. In a report of the parent study, Antoni et al. [3] found CBSM reduced indicators of social disruption. Women in CBSM condition remain engaged in social and interpersonal activities, compared with those in PE control condition. These findings supported that CBSM vs PE is effective in teaching utilization of social support. Social support introduces a safe environment for repetitive exposure to fears and further processing of the experience. It is possible that the observed benefits are attributable to differential social support. Future research should investigate whether the improvement in psychological adaptation is attributable to CBSM skills training or being in a supportive group environment or the combination.

Clinical Implications

Identifying for whom CBSM has the greatest effect can contribute to more cost-effective health care. While this study focused on pre-intervention distress level, other lines of research have focused on screening cancer patients with restricted psychosocial resources. For example, we have found that CBSM has greatest impact on benefit finding (but not on the other outcome measures) among women with more pessimistic outlooks [2]. Others have found that social support levels may moderate the impact of group-based psychosocial interventions in BCa patients [6, 33]. Developing a screening tool to identify BCa patients most in need of psychosocial intervention (e.g., based on distress, optimism and social support levels) may help in efforts to allocate limited medical resources for those with the greatest needs.

Study Limitations

The present findings should be interpreted with caution. These results were based on a secondary analysis of a trial conducted during the period 1998 – 2005 and may not generalize to contemporary samples of BCa patients receiving newer treatments. The sample was well-educated, middle class, and mostly non-Hispanic White women who self-selected into a trial focused on psychosocial intervention, and may have been more motivated than other patients undergoing BCa treatment. Also, the control condition used in this trial was not matched for attention and thus some of the results in the CBSM condition could be attributed to greater attention and the non-specific effects of being in a supportive group.

We conclude that beneficial effects of CBSM on psychological adaptation in BCa patients undergoing primary treatment depend partly on there being pre-intervention cancer-specific distress levels to work with. Future research should identify CBSM-specific and non-specific components that may account for intervention effects in this subgroup of patients. These findings may help guide the triaging of BCa patients early in the treatment process, while at the same time preserving resources for those most likely to benefit.

Highlights.

Effects of cognitive-behavioral stress management are moderated by level of distress.

Women with elevated cancer-specific distress after surgery benefit most from CBSM.

No differential improvement in affect occurred among low-distress women.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health [R01-CA-064710]. Laura Bouchard was supported by NIH/NCI training grant [CA193193]. Devika Jutagir was supported by NIMH training Grant [T32 CA009461[.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tallman BA, Altmaier E, Garcia C. Finding benefit from cancer. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54(4):481–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Klibourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20(1):20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kazi A, Wimberly SR, Sifre T, Urcuyo KR, et al. How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(6):1143–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antoni MH, Wimberly SR, Lechner SC, Kazi A, Sifre T, Urcuyo KR, et al. Reduction of cancer-specific thought intrusions and anxiety symptoms with a stress management intervention among women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;16(10):1791–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browall M, Kenne Sarenmalm E, Persson LO, Wengström Y, Gaston-Johansson F. Patient-reported stressful events and coping strategies in post-menopausal women with breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2016;25(2):324–33. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider S, Moyer A, Knapp-Oliver S, Sohl S, Cannella D, Targhetta V. Pre-intervention distress moderates the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;33(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groarke A, Curtis R, Kerin M. Cognitive-behavioural stress management enhances adjustment in women with breast cancer. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2013;18(3):623–41. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, Glaser R, Emery CF, Crespin TR, et al. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: a clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(17):3570–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchison SD, Steginga SK, Dunn J. The tiered model of psychosocial intervention in cancer: a community based approach. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(6):541–6. doi: 10.1002/pon.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrill EF, Brewer NT, O'neill SC, Lillie SE, Dees EC, Carey LA, et al. The interaction of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress symptoms in predicting depressive symptoms and quality of life. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17(9):948–53. doi: 10.1002/pon.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park CL, Chmielewski J, Blank TO. Post-traumatic growth: finding positive meaning in cancer survivorship moderates the impact of intrusive thoughts on adjustment in younger adults. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(11):1139–47. doi: 10.1002/pon.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordova MJ, Cunningham LL, Carlson CR, Andrykowski MA. Posttraumatic growth following breast cancer: a controlled comparison study. Health Psychology. 2001;20(3):176–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spencer SM, Lehman JM, Wynings C, Arena P, Carver CS, Antoni MH, et al. Concerns about breast cancer and relations to psychosocial well-being in a multiethnic sample of early-stage patients. Health Psychology. 1999;18(2):159–68. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsen PB, Widows MR, Hann DM, Andrykowski MA, Kronish LE, Fields KK. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after bone marrow transplantation for breast cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60(3):366–71. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antoni MH. Stress management for women with breast cancer. American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vargas S, Antoni MH, Carver CS, Lechner SC, Wohlgemuth W, Llabre M, et al. Sleep quality and fatigue after a stress management intervention for women with early-stage breast cancer in Southern Florida. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;21(6):971–81. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9374-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41(3):209–18. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Derogatis L. The affect balance scale (ABS) Baltimore: Clinical Psychometrics Research; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: User’s Reference Guide. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips KM, Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Blomberg BB, Llabre MM, Avisar E, et al. Stress management intervention reduces serum cortisol and increases relaxation during treatment for nonmetastatic breast cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(9):1044–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318186fb27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu L-t, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):424–53. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kline R. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behaviour sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monti DA, Kash KM, Kunkel EJ, Moss A, Mathews M, Brainard G, et al. Psychosocial benefits of a novel mindfulness intervention versus standard support in distressed women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(11):2565–75. doi: 10.1002/pon.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dale HL, Adair PM, Humphris GM. Systematic review of post-treatment psychosocial and behaviour change interventions for men with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(3):227–37. doi: 10.1002/pon.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, de Vries J, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychology. 2010;29(2):160–8. doi: 10.1037/a0017806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lechner SC, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weaver KE, Phillips KM. Curvilinear associations between benefit finding and psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):828–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horowitz M. Stress-response syndromes. 2. New York, NY: Aronson; 1986. pp. 241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janus-Bulman R. Shattered assumptions: Toward a new psychology of trauma. New York: Free Press; 1992. p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SA, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, et al. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(5):953–64. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Devineni T, Veazey CH, Galovski TE, Mundy E, et al. A controlled evaluation of cognitive behaviorial therapy for posttraumatic stress in motor vehicle accident survivors. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41(1):79–96. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meichenbaum D. Stress inoculation training. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helgeson VS, Cohen S, Schulz R, Yasko J. Group support interventions for women with breast cancer: who benefits from what? Health Psychology. 2000;19(2):107–14. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]