Abstract

Despite the rising cultural phenomenon of grandparents parenting grandchildren on a full-time basis due to problems within the birth parent generation, intervention studies with these families have been scarce, methodologically flawed, and without conceptual underpinnings. We conducted a randomized clinical trial (RCT) with 343 custodial grandmothers recruited from across four states to compare the effectiveness of behavioral parent training (BPT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and information only control (IOC) conditions at lowering grandmothers’ psychological distress, improving their parenting practices, as well as reducing the internalizing and externalizing difficulties of target grandchildren between ages 4 and 12. These outcomes were derived conceptually from the Family Stress Model and modeled as latent constructs with multiple indicators. Each RCT condition was fully manualized and delivered across 10 sessions within groups co-led by trained professionals and peer facilitators in community settings. Multi-domain second-order latent difference score models were performed on a full intent-to-treat basis to compare the three RCT conditions on changes in the above outcomes from baseline to post-intervention and from baseline to six months post-intervention. In general, while CBT and BPT interventions were both superior to IOC at both times of measurement on most outcomes, they differed little from each other. Effect sizes were generally in the moderate to large range and similar to those found in prior studies of BPT and CBT with traditional birth parents. We conclude from this research that evidence-based interventions focusing on appropriate skill development and behavioral change can yield positive outcomes within custodial grandfamilies.

Keywords: Custodial Grandparents, Parenting, Randomized Clinical Trial, Psychosocial Interventions, Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Interest in custodial grandfamilies (CGF), those where grandparents raise grandchildren without the involvement of custodial grandchildren’s (CGC) birth parents, has soared due primarily to traumatic events resulting in birth parents’ absence or inability to parent (Hayslip, Fruhauf, & Dolbin-MacNab, 2017). Such events include substance abuse, incarceration, child neglect, violence, and mental or physical illness. Although custodial grandmothers (CGM), who provide the bulk of this care, and their CGC face risk for psychological difficulties (Smith & Palmieri, 2007), studies of theoretically grounded psychosocial interventions for CGF are scarce.

McLaughlin, Ryder, and Taylor (2017) reviewed 21 psychosocial or physical health interventions for caregiving grandparents published from 2004 to 2014 involving either case management, cognitive behavioral or skills-based training, support groups, or psychoeducation. McLaughlin and colleagues concluded that “there is a paucity of strong evidence to support a definitive approach to intervention for grandparents raising grandchildren” (p. 526). In addition, no studies to date have compared the comparative efficacy of psychosocial interventions based upon a conceptual model that specifies key outcomes for CGM and CGC alike.

To address this gap, the present research involves a longitudinal randomized clinical trial (RCT) conducted across four states to compare the efficacy of two evidence-based interventions that are widely used with other family caregiver populations: Behavioral Parent Training (BPT) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Consistent with the family stress model (FSM; Conger, et al., 2002), we evaluate the extent to which each intervention beneficially modifies CGM’s psychological distress, CGM’s parenting behaviors, and CGC psychological difficulties.

That CGMs and CGC both face risk for psychological difficulties signifies that parenting is a major concern regarding these families (Hayslip & Kaminski, 2008). This is supported by extensive findings in the parenting literature that caregiver distress is related to poor parenting, poor parenting is related to children’s adjustment, and parenting mediates the link between caregiver distress and child adjustment (Rueger, Katz, Risser, & Lovejoy, 2011). Parenting quality also mediates the impact of distal stressors such as social and economic disadvantage, which are common among GCFs and impact children’s adjustment (Deater-Deckard, 1998; Hayslip et al., 2017). Notably, children raised by caregivers who are only mildly distressed face risk for internalizing and externalizing problems (Rubin & Burgess, 2002; (Rueger et al., 2011).

There is also concern over a possible intergenerational transmission of poor parenting by CGMs, given that some had difficulties in raising their own children and may face similar challenges in raising a grandchild (Gibson, 2005). Many CGMs are troubled by seeing how their offspring have fared and question their own parenting ability (Glass & Honeycutt, 2002). Some have difficulty with discipline and setting limits with CGC due to the conflicting nature of being both a grandparent and primary caregiver. In addition, many CGMs doubt their ability to parent effectively due to advanced age or poor health (Landry-Meyer & Newman, 2004).

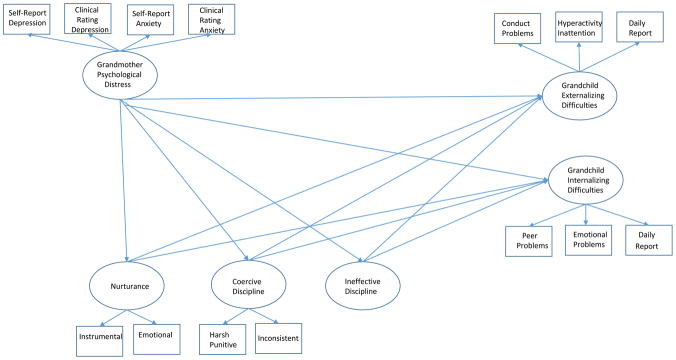

As depicted in Figure 1, the FSM (Conger, et al, 2002) is useful for identifying modifiable components of family process that are key to family members’ well-being and for studying how change in one model component may affect other family processes. The central tenet of the FSM is that the impact of caregivers’ distress on children’s adjustment is largely indirect through poor parenting. Thus, these three constructs are the major variables of interest in the present study. The findings of prior descriptive studies support the applicability of the FSM to CGFs (Smith, Cichy, & Montoro-Rodriquez, 2015a; Smith et al. 2017).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework and Measurement Model

Following the logic of the FSM, we specifically contrast two evidenced-based interventions in terms of their ability to yield changes in the outcomes depicted in Figure 1: (1) Behavior parent training (BPT) as per the Level 4 group version of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program (Sanders, Kirby, Tellegen, & Day, 2014); and (2) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) as per the Coping with Caregiving program originally developed by Gallagher-Thompson et al. (2002) for caregivers of persons with dementia. We compare these evidence-based interventions to each other as well as to a therapeutically inert control condition.

BPT programs follow the premise that poor parenting contributes to the development, progression, and maintenance of children’s disruptive behaviors. Accordingly, BPT interventions are aimed at changing caregivers’ behaviors, perceptions, communication, and understanding in order to effect desired changes in child behavior (Lundahl, Risser, & Lovejoy, 2006). Numerous studies with birth parents have shown diverse BPT programs to result in improved parenting, reduced caregiver distress, and decreased child behavior problems (Lundahl et al., 2006; Sanders et al., 2014). In addition, as BPT interventions reduce stressful child behavior, caregivers are likely to experience decreased psychological distress that may have partly originated from difficult interactions with the child (Beach, Kogan, Brody, Chen, Lei, & Murry, 2008).

The basic assumption of CBT is that individuals use adaptive cognitive and behavioral strategies to handle stressful situations by modifying negative thoughts and core beliefs and by increasing positive actions. These changes lead to better problem-solving and coping which then improves affective functioning (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). A key goal of CBT is to improve the ability to regulate negative affect in the face of both daily and major stressful events. Importantly, CBT is effective at reducing older caregiver distress and improving performance on care-related tasks to which anxiety about failure is attached (Marquett et al., 2013).

Our RCT comparison of BPT to CBT with CGM s is warranted on several grounds. First, CGMs are confronted by a myriad of chronic and daily stressors (Hayslip et al., 2017) which may undermine their ability to respond appropriately to child care tasks irrespective of their parenting skills (Conley, Caldwell, Flynn, Dupre, & Rudolph, 2004). Second, reductions in caregiver distress are linked to less child internalizing and externalizing difficulties even after accounting for the potential mediation of improved parenting behavior (Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gradner, 2009). Third, because BPT is limited in terms of teaching caregivers to deal with stress, parenting scholars have concluded that interventions more clearly aimed at reducing stress are also needed (Heath, Curtis, Fan, & McPherson, 2015; Kazdin & Whitley, 2003).

Based on the FSM (Figure 1) we expect both BPT and CBT to yield improved CGC adjustment as a result of improved parenting. The main difference is that improved parenting is expected to result from the reduction of CGM distress in CBT, whereas improved parenting is expected to result from increased parenting skill and knowledge in BPT. Moreover, we expect BPT to reduce CGM distress indirectly by reducing the negative impact of CGC psychological difficulties on CGM mental health. (Beach et al., 2008). Therefore, CBT and BPT are expected to influence positively the same outcomes, albeit through different causal mechanisms.

The following hypotheses are tested:

-

Hypothesis 1

In comparison to IOC, families randomly assigned to either BPT or CBT will show significantly more improvement at immediate post-intervention and six months later on CGM psychological distress, CGM parenting practices, and CGC psychological difficulties.

-

Hypothesis 2

Families randomly assigned to receive either BPT or CBT will not differ significantly from each other at immediate post-intervention and six months afterwards on CGM psychological distress, CGM parenting practices, and CGC psychological difficulties.

Method

Participants

A sample of 343 CGM was enrolled across four states (California, Ohio, Maryland, and Texas). Inclusion criteria were that CGMs provided care to a CGC between ages 4 to 12 for at least 3 months in absence of the birth parents, were fluent in English, could attend 10 two-hour group sessions, had not previously received BPT or CBT, and self-identified as White, Black, or Hispanic. If a CGM cared for multiple grandchildren aged 4 to 12, then a target grandchild (TGC) was selected by asking her to identify the child being the “most difficult” to care for.

Recruitment was identical across sites, involved multiple approaches (e.g., media announcements, schools, service providers), and directed by the Principal Investigator at each site. The RCT was described as providing “information to help grandmothers get through the difficult job of caring for grandchildren in changing times.” Although 540 CGMs met the inclusion criteria, only 343 could participate at specific times and locations. Approval was obtained by the IRB at each university. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Table 1 shows background characteristics of the 343 CGM and their TGC by RCT condition. The CGMs were in their late 50s (M age = 58.46, SD = 8.22), mostly Caucasian (44%) or African American (43%), raising TGC who were equally male or female and who were on average, approximately 8 years of age (M = 7.83, SD = 2.55). Most (62%) were unmarried, unemployed (58%), and completed at least some college (64%). Primary reasons leading to TGC care were parents’ drug abuse, child abuse, incarceration, unwillingness, or mental illness.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample by condition.

| Condition |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPT (n = 115) | CBT (n = 128) | IOC (n = 100) | ||

| Grandchild (GC) Age | 7.60 (2.62) | 7.69 (2.61) | 8.20 (2.43) | 7.83 (2.55) |

| Grandmother (GM) Age | 58.03 (8.81) | 57.75 (8.02) | 59.83 (7.68) | 58.54 (8.17) |

| Total GC Cared For | 1.88 (1.14) | 1.73 (.98) | 1.72 (.95) | 1.78 (1.02) |

| GC Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 62 (18.1) | 60 (17.5) | 53 (15.5) | 175 (51) |

| GM Race, n (%) | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 50 (14.6) | 55 (16) | 47 (13.7) | 152 (44.3) |

| African American | 53 (15.5) | 55 (16) | 41 (12) | 149 (43.4) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 10 (2.9) | 16 (4.7) | 12 (3.5) | 38 (11.1) |

| Other | 2 (.06) | 2 (.06) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.2) |

| Performance Site, n (%) | ||||

| Texas | 34 (9.9) | 26 (7.6) | 35 (10.2) | 95 (27.7) |

| Ohio | 28 (8.2) | 34 (9.9) | 30 (8.7) | 92 (26.8) |

| California | 24 (7.0) | 37 (10.8) | 21 (6.1) | 82 (23.9) |

| Maryland | 29 (8.5) | 31 (9.0) | 14 (4.1) | 74 (21.6) |

| Number of Sessions Attended, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 21 (6.1) | 31 (9.0) | 18 (5.3) | 70 (20.4) |

| 1–6 | 31 (9.0) | 37 (10.8) | 18 (5.3) | 86 (25.1) |

| 7–10 | 63 (18.4) | 60 (17.5) | 64 (18.7) | 187 (54.5) |

| GM Marital Status, n (%) | ||||

| Married | 52 (15.2) | 50 (15.6) | 30 (8.7) | 132 (38.5) |

| GM Employment, n (%) | ||||

| Employed | 46 (13.4) | 54 (15.7) | 45 (13.1) | 145 (42.3) |

| GM Education, n (%) | ||||

| < High School | 15 (4.4) | 22 (6.4) | 13 (3.8) | 50 (14.6) |

| High School Graduate | 26 (7.6) | 26 (7.6) | 20 (5.8) | 72 (21) |

| Some College | 55 (16) | 55 (16) | 46 (13.4) | 156 (45.5) |

| Bachelors or above | 19 (5.5) | 25 (7.3) | 21 (6.1) | 65 (19.0) |

| Annual Family Income, n (%) | ||||

| < 15k – 30k | 60 (17.5) | 77 (22.4) | 53 (15.5) | 190 (55.4) |

| 30k – 75k | 38 (11.1) | 37 (10.8) | 33 (10) | 103 (31.5) |

| 75k + | 17 (5) | 14 (4.1) | 14 (4.1) | 45 (13.1) |

| Reasons for Care | ||||

| Parental Drug Abuse | 50 (14.6) | 65 (19.0) | 47 (13.7) | 162 (47.2) |

| Parental Child Abuse | 41 (12) | 50 (14.6) | 41 (12) | 132 (38.5) |

| Incarceration | 33 (9.6) | 33 (9.6) | 31 (9.0) | 97 (28.3) |

| Parental Unwillingness | 26 (7.6) | 34 (9.9) | 20 (5.8) | 80 (23.3) |

| Parental Mental Health | 25 (7.3) | 26 (7.6) | 21 (6.1) | 72 (21) |

| Parental Death | 11 (3.2) | 15 (4.4) | 9 (2.6) | 35 (10.2) |

| Teen Pregnancy | 9 (2.6) | 7 (2.0) | 10 (2.9) | 26 (7.6) |

| Parental Physical Health | 4 (1.2) | 6 (1.7) | 4 (1.2) | 14 (4.1) |

| Other | 63 (18.6) | |||

Note: BPT = Behavioral Parent Training, CBT = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, IOC = Information Only Control. All main efforts for and interactions with condition were statistically non-significant (p > .05).

Materials and Procedure

Grandmothers were randomly assigned by site to either BPT (n =115), CBT (n = 128), or IOC (n = 100) via a computer program created by an outside programmer using the Mersenne Twister Number Generator. Each condition was delivered across 10 two-hour sessions in groups co-led by a professional leader and a peer CGM in community settings. The professionals received two day-long training specific to their condition, and conducted practice groups with their respective peer leader prior to the RCT. All leaders were blind to study hypotheses.

Those CGMs assigned to BPT received Level 4 group Triple P (Sanders et al., 2014), selected because it is similar to other empirically supported BPT programs, is the most highly structured BPT available, targets low-and high risk-families, is delivered in groups, and yields both short and long-term effects on children’s psychological outcomes, parenting practices, and caregiver adjustment (Sanders et al., 2014). Sessions involved training to increase positive CGM-CGC interactions by rewarding good behavior, ignoring unwanted behavior, and providing clear requests and consequences. This was done through videos and short lectures, interactive exercises, modeling, behavior charting, and review of homework assignments. The standard eight-week Triple P program was modified by adding a session on CGC self-esteem and an extra one on managing misbehavior. Although these modifications were made to insure that the BPT condition encompassed 10 sessions, they fully complied with BPT guidelines and procedures.

Those CGMs assigned to CBT received an adaptation of the Coping with Caregiving (CWC) program developed by Gallagher-Thompson et al. (2002) for dementia caregivers, selected for the present study because it is evidenced-based in terms of reducing psychological distress with family caregivers of similar age to CGM, follows the underlying logic of CBT, is manualized to maximize leader training and fidelity, and is limited to 10 sessions that are deliverable in group formats (Gallagher-Thompson, et al, 2002). Sessions were designed to improve CGMs’ ability to regulate negative affect in the face of daily and major stressors. Participants were taught to use adaptive cognitive and behavioral strategies (e.g., modify negative thoughts, increase positive activity, relaxation, and enhanced problem-solving). Modifications to CWC were limited to making CBT materials and exercises relevant to CGM (i.e., sources of stress, examples of unhelpful thinking, homework assignments for stress management, future planning goals, and pleasant activities).

Those CGMs randomly assigned to IOC received readings on relevant topics (e.g., importance of self-care, keeping CGC healthy, discipline) compiled for group discussions. There were no attempts to alter CGMs’ behaviors, nor were any skills imparted. The IOC controlled for non-specific factors (expectancy for change, contact with leaders and peers, affirmation, repeated measurement) that might influence outcomes in the absence of treatment (Kazdin, 2003).

All RCT conditions were manualized to facilitate leader training, provide structure and consistency to intervention delivery, and permit future replication. Work books were provided to facilitate understanding and retention of content. Free child care and meals were provided to foster attendance. Treatment fidelity was monitored by trained raters via checklists derived from the manual for each intervention as well as the IOC. Those CGMs who missed a group session were encouraged to receive a make-up session from their professional leader either by phone or in-person. To assure treatment fidelity, all make-up sessions covered the missed content exactly as specified in the corresponding treatment manual for each RCT condition.

Baseline data were collected within one month before each RCT group began (T1), post-intervention interviews occurred within a month after each group ended (T2), and follow-up interviews occurred six months after each post-intervention interview (T3). Combined phone and in-person interviews were conducted across all sites by trained graduate students from mental health disciplines blind to condition The indicators for each latent construct in Figure 1 are described below. All reported Cronbach alpha values were derived from the study sample.

Measures

GCM Psychological Distress

Indicators of this construct encompassed self-report and clinical ratings of depression and anxiety. Depressive symptoms were self-reported with the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Potential scores ranged from 0 to 60 (α = .91); higher scores index more symptoms. Anxiety was self-reported with the 5-item Overall Anxiety Severity and Intensity Scale (OASIS; Norman, Hami, Means-Christianson, & Stein, 2006). Potential scores range from 0 and 20 (α =.86), with higher scores representing greater anxiety. CGM depression and anxiety were also rated by graduate students from mental health fields trained to achieve satisfactory agreement (.60 kappa and .90 intraclass correlation coefficient) with gold standard ratings. Depression was rated with the 10-item Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery & Asberg, 1979). Raters were trained to criterion performance on a semi-structured clinical interview (Williams, 1988). Global scores (range = 0 to 60) were formed by adding ratings across all 10 symptoms (α = .87). Anxiety ratings were obtained with the 14-item Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1959), which is widely used in clinical research. Each item is scored on a scale of 0 (not present) to 4 (severe), with a total score range of 0–56 (α = .88.). Raters were trained to criterion on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Interview Guide (Bruss, Gruenberg, Goldstein, & Barber, 1994).

Parenting Practices

Measures of the broader constructs of discipline and nurturance were included because they comprise the most influential parenting mechanisms known to influence children’s adjustment problems (Locke & Prinz, 2002). Measures were selected to be brief, easy to administer, and contain content relevant to children ages 4–12.

Three types of discipline (Effective, Inconsistent, and Punitive/Harsh) were measured with the Parenting Practices Inventory (PPI), a 17-item instrument developed for the Fast Track Project to assess key disciplinary styles related to children’s adjustment outcomes (Lochman, 1995). The PPI was reduced to 15 items in the present study because Smith et al. (2015b) recommend that that two Effective and one Inconsistent item be removed for use with CGMs.

CGMs rated the 15 PPI items on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 “never” to 4 “often.” Four items tapped Effective discipline (e.g., “How often do you have difficulty controlling your grandchild?”) and summed to a total score with a possible range of 4–16 (α = .83). Six items tapped Inconsistent Discipline (e.g., “How often does your grandchild manage to get around the rules you set for him/her?”) and summed to a total score with a possible range of 5–20 (α =.79). Five items tapped punitive Punitive/Harsh Discipline (e.g., “How often do you yell at your grandchild?”) and summed to a total score with a possible range of 5–20 (α =.73).

The Inconsistent and Punitive/Harsh Discipline scales of the PPI were each modeled as indicators of coercive parenting given the prominence of this construct in the parenting literature (Patterson, 1982). The Ineffective Discipline latent construct was modeled by using the PPI ineffective scale as a single indicator, with its residual variance fixed to 1 minus the scale reliability times the scale variance to account for measurement error.

Two indicators of the nurturance parenting construct were selected in line with the view that this aspect of parenting involves providing a positive atmosphere for the parent-child relationship and the child’s emotional development through both emotional expressions (e.g., communicating acceptance) and instrumental acts (e.g., playing together) (Locke & Prinz, 2002). Instrumental nurturance was measured by the 10-item Supportive Engaged Behavior (SEB) subscale of the Parent Behavior Inventory (Lovejoy, Weiss, O’Hare, & Rubin, 1999). Items (e.g., “I comfort my grandchild when s/he seems scared, upset, or unsure.”) were rated by CGMs from 0 “not at all” to 5 “very true” and summed to yield a total score with a potential range of 0–50 (α = .88). Emotional nurturance was assessed with the 10-item Positive Affect Index which measures the degree to which caretakers report trust, fairness, respect, affection, and understanding between themselves and their child, as well as their perception of how the child feels about them along these dimensions (Bengtson & Schrader, 1982). CGMs rated each item (e.g., “How much affection do you have toward your grandchild?”) from 0 “none” to 4 “a great amount” and total scores were computed by summing all items (potential range = 0–40, α = .87).

CGC Internalizing and Externalizing Difficulties

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 2001) and a modification of the Parent Daily Report (PDR; Chamberlain & Reid, 1987) were used to measure CGC Internalizing and Externalizing difficulties with CGMs as informants. The PDR includes a checklist of internalizing (10 items) and externalizing (12 items) behavior problems where CGMs indicated the presence of each behavior on a scale from 0 “not at all” to 2 “a lot” during the past 24 hours. One PDR administration took place by phone, with another occurring in-person within two weeks. Scores across the two points were averaged for each item and then separate internalizing (α = .97) and externalizing (α = .98) scores were calculated by summing the averages of their respective items.

The broadband internalizing and externalizing subscales from the parent-informant version of the SDQ were also used with CGMs as informants. Externalizing difficulties were derived by summing the SDQ Hyperactivity-Inattention and Conduct Problems scales (potential range = 0 to 20; α = .75), and Internalizing difficulties were derived by summing the SDQ Emotional Symptoms and Peer Problems scales (potential range = 0 to 20, α = .74). Each scale contained five items that were rated by CGMs regarding the target CGC on a 3-point scale from 0 (not true) to 2 (certainly true). Higher scores indicate greater levels of each construct.

Analytic Plan

Two multi-domain second-order latent difference score models, from baseline to post-intervention and from baseline to six months post-intervention, were fitted to the first-order factors of CGC Internalizing symptoms, CGG Externalizing symptoms, Nurturance, Coercive Discipline, Ineffective Discipline, and CGM psychological distress as per Figure 1 using Mplus 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2016). Each RCT condition was compared to the others in separate analyses where condition was regressed onto the slope (i.e. estimate of change) of each latent construct in the model. Analyses were conducted on an intent-to-treat basis (Gupta, 2011) as specified by RCT guidelines. Missing data were accommodated with robust full information maximum likelihood (FIML), employing self-rated measures of grandmother health (from 0 “poor” to 4 “excellent”) at baseline and post-test as auxiliary variables to help meet FIML’s assumption of data being missing at random (Enders, 2013).

Using each conditional second-order latent growth model, the model-implied specific second-order intercepts and slopes that were determined by condition for each outcome. From these values, the model-implied latent construct means for the different time-points were computed in the metric of their first-order factors’ indicator variables. Standardized effect sizes (ES) for differences in latent change means by groups were computed as per Hancock (2001). Sample size planning was conducted using a combination of analytic and Monte Carlo simulation methods (Hancock & French, 2013), whereby minimum critical ES were specified for focal model parameters, expected attrition was coded into the simulation, and the minimum sample size was determined in order to achieve at least .80 power for all focal parameters.

Results

Table 1 shows that 187 (54.5%) of the 343 enrolled CGMs attended between 7–10 sessions, with only 70 (20.4%) attending no sessions at all. A chi-square analysis revealed no significant difference in attendance by RCT condition (X2 (4) = 7.40, p = .12). Of the 273 CGMs who attended treatment, 89 (32.6%) used make-up sessions. In turn, 75 (84.3%) of these CGM used only 1 or 2 make-ups. A chi-square analysis showed no significant difference in make-ups by RCT condition (X2 (4) = 0.63, p = .96).

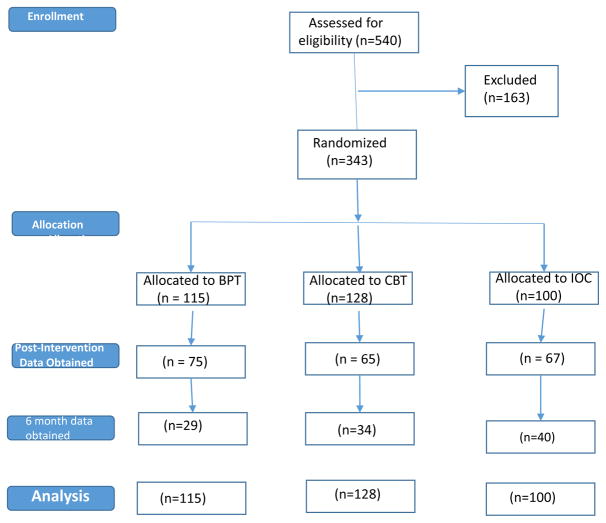

More CGMs assigned to CBT (44%) attended no sessions compared to those in BPT or IOC. The CONSORT flow chart in Figure 2 shows that data were obtained from 207 CGMs at T2 (60%) and 103 CGMs at T3 (30%). Despite these losses to follow-up, all 343 CGMs were included in the analyses as per FIML. The most common reasons for missingness were CGMs becoming unreachable or requesting no further contact.

Figure 2.

CONSORT Flow Chart

Table 2 shows results of the six second-order difference score model conducted from T1 to T2 and from T1 to T3, in which RCT conditions were compared to one another at both measurement periods on all outcomes. Model fit was good for each model tested (Comparative Fit Index > .94; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation < .04; Standardized Root Mean Square Residual < .08). Also shown for each RCT comparison is the unstandardized path estimate for the slope factor regressed on the RCT condition code predictor (i.e., group difference in latent change score), as well as the corresponding standardized ES and p-values.

Table 2.

Effects of RCT condition on changes in latent constructs across times of measurement.

| Baseline (T1) to posttest (T2) | Baseline (T1) to six-month follow-up (T3) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| BPT vs CBT | BPT vs IOC | CBT vs IOC | BPT vs CBT | BPT vs IOC | CBT vs IOC | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Construct | Est. | SE | p | ES | Est. | SE | p | ES | Est. | SE | p | ES | Est. | SE | p | ES | Est. | SE | p | ES | Est. | SE | p | ES |

| Grandchild Externalizing | .31 | .49 | .53 | −.14 | −.46 | .50 | .18 | .32 | −1.06 | .45 | .01 | −.50 | −.47 | .79 | .55 | −.28 | −1.08 | .59 | .03 | −.66 | −1.55 | .53 | .002 | −.98 |

| Grandchild Internalizing | .36 | .35 | .31 | .22 | −.23 | .39 | .14 | −.14 | −.70 | .36 | .03 | −.44 | −.19 | .55 | .73 | .11 | −.89 | .55 | .05 | −.51 | −1.15 | .49 | .01 | −.66 |

| Grandmother Distress | .34 | 1.22 | .78 | .05 | .34 | 1.25 | .39 | .05 | 1.34 | 1.47 | .14 | .21 | −3.13 | 1.70 | .07 | −.69 | −2.72 | 1.60 | .05 | −.64 | −.67 | 1.54 | .33 | −.16 |

| Coercive Discipline | −.55 | .37 | .14 | −.29 | −1.03 | .40 | .005 | −.56 | −.58 | .41 | .08 | −.31 | .21 | .51 | .68 | .15 | −.34 | .53 | .26 | −.24 | −.58 | .43 | .09 | −.40 |

| Ineffective Discipline | −.39 | .40 | .32 | −.27 | −.82 | .42 | .03 | −.57 | −.78 | .46 | .04 | −.54 | .02 | .85 | .98 | .01 | −.81 | .66 | .11 | −.40 | −1.45 | .56 | .005 | .73 |

| Nurturance | −.30 | .68 | .66 | −.11- | .48 | .70 | .25 | .18 | .87 | .64 | .09 | .33 | .40 | 1.10 | .72 | .12 | .75 | 1.14 | .26 | .23 | 1.27 | .97 | .07 | .39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| CFI = .95 | CFI = .95 | CFI = .95 | CFI = .93 | CFI = .93 | CFI = .94 | |||||||||||||||||||

| RMSEA = .04 | RMSEA = .04 | RMSEA = .04 | RMSEA = .04 | RMSEA = .04 | RMSEA = .04 | |||||||||||||||||||

| SRMR = .06 | SRMR = .06 | SRMR = .06 | SRMR = .08 | SRMR = .07 | SRMR = .08 | |||||||||||||||||||

Note: Unstandardized estimates (Est.) for the effect on RCT predictor code on slope are reported. p is shown for two-tailed tests involving BPT vs CBT comparisons. p is shown for one-tailed tests involving BPT vs IOC and CBT vs IOC comparisons due to directional hypotheses.

Regarding change in model constructs from T1 to T2, no significant differences were observed when comparing BPT to CBT. The comparison of BPT to IOC however, shows that reductions in both coercive discipline and ineffective discipline were significantly greater for CGMs in the BPT conditions (with ES of −.56 and −.57, respectively). The comparison of CBT to IOC shows that reductions in both CGC internalizing and externalizing symptoms, as well as in ineffective discipline, were significantly greater for those assigned to CBT (with ES ranging from −.44 to −.54). Although the CBT condition also yielded both greater reduction in coercive discipline (p = .08) and increased nurturance (p =.09) in comparison to IOC, these differences fell just shy of statistical significance. There were no statistically significant T1 to T2 differences among all three RCT conditions in terms of CGM psychological distress.

As for changes from T1 to T3, there were no statistically significant differences between the BPT and CBT conditions although reductions in CGM psychological distress were somewhat greater for the BPT condition (p = .07; ES = −.69). Comparisons of BPT to IOC showed significantly greater reductions in both CGC externalizing (p = .03) and internalizing (p = .05) difficulties as well as in CGM distress (p = .05) (ES sizes from −.51 to −.64). There was also a non-significant trend for BPT to yield greater reductions in ineffective discipline (p = .11; ES = .40). Comparison of CBT to IOC showed significant reductions in CGC externalizing (p = .002) and internalizing (p = .01) difficulties (ES from −.51 to −.66). Although just shy of statistical significance, the CBT condition also trended toward greater reduction in coercive discipline (p = .09; ES = −.40) and increased nurturance (p = .07; ES = .39) in comparison to IOC.

Table 3 presents the estimated latent means for all latent outcome constructs by RCT condition at each time of measurement. Of note are the consistent reductions from T1 to T3 intervention on CGC internalizing and externalizing symptoms across all conditions. However, these reductions were smallest within the IOC condition.

Table 3.

Estimated latent means for latent outcome constructs at baseline, posttest, and six-month post-intervention by RCT condition.

| BPT | CBT | IOC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Outcome Construct | Baseline | Posttest | 6-month | Baseline | Posttest | 6-month | Baseline | Posttest | 6-month |

| Grandchild Externalizing | 7.83 | 7.27 | 6.57 | 8.23 | 7.37 | 7.01 | 7.80 | 7.70 | 7.50 |

| Grandchild Internalizing | 3.97 | 3.51 | 2.93 | 3.84 | 3.08 | 2.84 | 3.74 | 3.49 | 3.45 |

| Grandmother Distress | 14.69 | 14.10 | 11.38 | 14.32 | 13.75 | 13.16 | 13.08 | 11.87 | 12.28 |

| Coercive Discipline | 8.09 | 7.11 | 7.42 | 7.91 | 7.30 | 6.99 | 8.14 | 7.96 | 7.72 |

| Ineffective Discipline | 4.11 | 3.47 | 3.49 | 4.16 | 3.71 | 3.37 | 4.05 | 4.12 | 4.16 |

| Nurturance | 34.69 | 35.03 | 35.24 | 34.29 | 34.87 | 34.92 | 34.06 | 34.01 | 33.89 |

Regarding CGM psychological distress, BPT and CBT both showed continued improvements (p = .05) from T1 to T3. However, these reductions were most pronounced for BPT. Although there was a slight reduction in CGM distress for the IOC from T1 to T2, this pattern was reversed at T3. Only CBT showed continued improvements from T1 to T3 on ineffective discipline, coercive discipline, and nurturance. In contrast, BPT showed improvements from T1 to T2 that leveled off at T3. The IOC condition showed continued deterioration from T1 to T3 on both nurturance and ineffective discipline. However, coercive discipline continually decreased (p = .05) from T1 to T3 for CGMs in the IOC condition.

Discussion

We conducted a RCT to examine the relative efficacy of BPT, CBT, and IOC conditions at reducing CGM psychological distress, improving CGM parenting practices, and lessening CGC psychological difficulties at post-intervention (T2) and six months afterwards (T3). According to the FSM (Conger et al., 2002), these outcomes are salient because children’s psychological adjustment depends upon the quality of parenting they receive. In turn, parenting quality is adversely affected by a caregiver’s emotional distress. Consistent with our hypotheses, BPT and CBT were largely superior to IOC at producing positive changes in these key outcomes across both times of measurement with minimal differences found between BPT and CBT.

Our previously reported finding of virtually no difference between our three RCT conditions on a measures of treatment satisfaction, suggests that each condition was appraised by CGMs as being equally credible and beneficial (Smith, Strieder, Greenberg, Hayslip, & Montoro-Rodriquez, 2016). This similarity of appraisals is unsurprising given that all three conditions were meaningfully structured, led by professionals, permitted personal expression in a safe group environment, and provided useful information to participants. The key difference however, is that only the BPT and CBT interventions focused on behavior change and the adoption of distinctive new skills. This key distinction likely explains their difference in terms of producing positive outcomes in comparison to IOC.

Treatment-Related Changes on Key Outcomes

Although latent means for CGM psychological distress decreased from baseline to T2 across all three RCT conditions, there were no statistically significant between-group differences. This improvement in CGM emotional well-being may have been due to such non-specific factors as interacting with peers and receiving attention from group leaders (Kazdin, 2003). Importantly however, CGM distress at T3 for IOC regressed towards baseline level whereas continued improvements were observed over time for both CBT and BPT.

At T3 BPT was superior to both CBT and IOC at reducing CGM psychological distress, which is in line with meta-analytic findings showing that that average ES for long-term change in parental adjustment (.48) is larger than for short-term (.34) effects in studies of Triple P with birth parents (Sanders et al., 2014). Although the mechanisms behind treatment change for BPT have been insufficiently studied to date, a common explanation for such long-term changes in parental adjustment is that through learning new parenting skills caregivers develop greater confidence and competence regarding their ability to control children’s behaviors, which then reduces their feelings of distress (Heath et al., 2015).

It is noteworthy that both CBT and BPT were more effective than IOC from baseline to T2 at reducing coercive and ineffective discipline even though BPT alone explicitly targeted these parenting behaviors. The observed effectiveness of CBT at improving parenting practices may be explained by findings consistent with the Family FSM among birth parents that parental negative affect (e.g., anger, irritability, hostility, fear, sadness) is a reliable correlate of parenting behaviors in both community and clinical samples (Rueger et al., 2011). In particular, negative affect is associated with parenting behaviors that are physically controlling, coercive, and intrusive. By helping CGMs recognize and more effectively regulate their emotions, CBT may have facilitated less coercive and more supportive and engaged parenting behaviors independent of parent training. This reasoning is underscored by an earlier study based upon the FSM where the impact of CGM’s psychological distress on their parenting practices was found to be mediated by their coping resources (Smith et al, 2015a).

It is surprising that CBT was more effective than both BPT and IOC at increasing CGMs supportive/engaged parenting at T2 and T3. One possibility is that heightened positivity resulting from CBT may enhance CGM’s willingness and/or ability to engage in activities with the CGC, and thereby increase overall affection and warmth in the CGM-CGC relationship (Rueger et al., 2011). Because CBT focuses on improving thought processes and enhancing emotionality, CGM’s interactions with CGC may improve as they become less irritable and withdrawn and appraise the caregiving situation more positively over time. Even though CGMs were encouraged in BPT to become more engaged with the CGC, the main goal was to decrease coercive exchanges in order to diminish children’s problem behaviors (Nowak & Heinrichs, 2008) rather than to alter CGMs’ emotions and appraisals of caregiving, as was true in CBT.

Another unexpected finding was the superiority of CBT over both BPT and IOC at T3 in reducing both coercive and ineffective discipline. Whereas the latent means for both constructs regressed slightly towards baseline within BPT, they continued to improve at T3 within the CBT condition. It may be that the specialized parenting skills taught in BPT (e.g., behavioral charting; compliance routines) are more difficult for CGMs to remember and implement over an extended time than the less technical skills acquired during CBT (e.g., relaxation techniques, cognitive reframing). It has also been argued that CBT is superior to BPT at helping caregivers to disregard irrelevant stimuli associated with stressors that detract from their ability to parent effectively (Wahler, Cartor, Fleischman, & Lambert, 1993).

Although both the externalizing and internalizing difficulties of CGCs reported by CGMs were lower across all three RCT conditions at T2 and T3, only CBT yielded significantly greater improvement than IOC at T2. However, at T3, both BPT and CBT showed significant reductions in these outcomes from baseline in comparison to IOC. Two explanations in the parenting literature for long-term effects on children’s behavior due to BPT may similarly apply to GCMs. One is that positive changes in parenting behaviors affect children’s ability to adapt to stress through better emotional regulation. A second explanation is that children’s beliefs regarding self-worth, personal control, and stability in the child-caregiver relationship are affected positively after caregivers attend BPT (Sandler, Schoenfelder, Wolchik, & MacKinnon, 2011). Both explanations imply changes in children that occur gradually over time and not likely to be manifested immediately after their caregiver receives BPT.

Our finding that CBT was also effective at reducing CGC externalizing and internalizing difficulties suggests that, for some CGMs, it may be beneficial to target psychological distress in addition to or instead of parenting deficits, given that CGM distress may be the main antecedent for any parenting difficulties that adversely affect CGC outcomes. Not only do the emotional management skills learned through CBT enhance one’s abilities to deal effectively with negative mood which then permits more positive CGM-CGC interactions, but enhanced CGM emotional regulation via CBT may also reduce levels of stress within the family and provide positive role modeling for CGC’s own emotional self-regulation (Deater-Deckard, 1998; Smith et al., 2015a).

That both BPT and CBT were found to produce long-term changes in CGC internalizing and externalizing difficulties is of high public health significance in view of findings with divorced and bereaved families that changes in these particular outcomes eventually lead to such long-term outcomes as lower drug use, fewer sexual partners, and greater self-esteem (Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein, & Winslow, 2015). Determining whether or not similar long-term outcomes would be experienced by CGC is a critical direction for future intervention research.

Interpretation of Effect Sizes

It is noteworthy that the ES observed in the present study are similar to those found in intervention research with birth parents. In the afore mentioned meta-analysis of Triple P, Sanders et al. (2014) reported significant short-term effects for children’s social, emotional and behavioral (SEB) outcomes (d = .473); parenting practices (d = .578); and parental adjustment (d = .340). Significant long-term treatment effects were likewise reported for child SEB (d =.525); parenting practices (d =.498); and parental adjustment (d =.481). Our similar ES suggest that Triple P is equally effective at reducing CGM distress, improving CGM parenting, and facilitating the psychological adjustment of CGC in both the short and long-term. Yet, because many evidence-based forms of BPT exist besides Triple P, research is needed to examine the efficacy and appropriateness of diverse types of parent training with grandfamilies (Kirby, 2015).

Although there are no similar meta-analyses regarding CBT interventions with birth parents, studies have shown ES of at least one half of a standard deviation difference between CBT treatment and control groups at reducing parental stress (Deater-Deckard, 1998). Perhaps ES for CBT did not reach this magnitude in the present study because CGMs were not screened for elevated depression or anxiety, thereby leaving little room for change on these indices. Given that negative affect associated with everyday hassles in non-clinical samples can adversely affect parenting behaviors (Rueger et al., 2011), emotional states other than depression and anxiety may be better measures of CGM outcome. For example, Kirby and Sanders (2012) discovered through focus groups with caregiving grandparents that guilt, frustration, unwanted obligation, and fatigue were most problematic for them as caregivers. An important future goal is to determine which specific negative emotions and unhelpful cognitions are most detrimental to CGM and targeted as intervention outcomes.

Our observed ES may be somewhat conservative given that we did not screen for high risk families. Instead, from a preventive science perspective, we viewed our CBT and BPT conditions as universal interventions that may either promote positive development, prevent problems from occurring, or remediate existing problems within the overall target population Kellam & Langevin, 2003). The present ES might also be conservative due to our ITT analysis and the likely dilution of treatment effects associated with 45% of the CGM s attending less than seven sessions (Gupta, 2011). At the same time, however, it is noteworthy that only 20% of CGMS failed to attend at least one session which is superior to the 25 to 50% of birth parents scheduled to begin BPT who never attend a single session (Chaco et al., 2016). Nevertheless, identifying strategies for increasing first time attendance at interventions designed for grandfamilies is critical to insure that those most in need actually attend so that treatment effects can be maximized (see Smith et al., 2016).

Given our findings that CBT and BPT were both more effective than IOC at producing positive changes in study outcomes, it is tempting to conclude that greater ES may be achieved by combining CBT and BPT elements into one intervention. Along these lines, Kirby and Sanders (2014) developed and tested a variant of Level 4 Triple P designed to meet the unique needs of families where grandparents regularly assist birth parents with child care. They added newly conceived sessions on handling relationship conflicts with birth parents and on teaching grandparents how to cope with their unhelpful emotions. Although significant short-term improvements were found on grandparent-reported child behavior problems, parenting confidence, grandparent depression, anxiety, as well as improved relationships with the parent that were maintained at six-month follow-up (Kirby & Sanders, 2014), there were no differences from a control group on the main Triple P outcome of reducing dysfunctional parenting.

The inability of Kirby and Sanders (2014) grandparent Triple P to change dysfunctional parenting illustrates the concern that a dilution of two treatments may end up being less effective than a full or more complete dose of the primary intervention (see Kazdin, 2005). Added sessions resulting from combined treatments also raise questions concerning incremental costs in relation to incremental benefits (Kazdin, 2005). Perhaps a better approach, as hinted at by the present findings, would be to assess the unique needs of each CGF and then match that family with the most appropriate intervention. For example, CGMs with high levels of stress and poor coping skills may be best suited for CBT. In contrast, those with deficient parenting skills and who care for grandchildren who display highly disruptive behaviors may be best suited for BPT.

Study Limitations and Conclusions

Limitations of the present research must be recognized when interpreting our findings. Although indices of CGM psychological distress included both self-reports and clinical ratings, all measures of parenting practices and CGC psychological difficulties were obtained solely from CGMs. It is possible that cognitive biases associated with CGM psychological distress may have contributed to the results reported here regarding changes in CGC difficulties. This concern is offset, however, by Triple P meta-analyses showing that both parents’ reports of SEB) outcomes and child-observations produced significant ES (Sanders et al., 2014). Although caregivers’ reports of parenting are retrospective and may be affected by social desirability, they are more comprehensive and wider in scope than observational methods (Locke & Prinz, 2002).

Another limitation concerns the missing data that we encountered. Even though the amount of missing data increased substantially across times of measurement, our use of FIML estimation allowed us to compensate considerably for holes in the overall matrix of data. This was further enhanced by using CGM physical health as an auxiliary (or proxy for missingness) and by knitting together information within the context of a strong conceptual model (Enders, 2013). Moreover, the degree of attrition in the present study was less than what typically occurs in similar intervention research with birth parents (Chaco et al., 2016).

Several limitations involve our sample which consisted primarily of White and African American families with minimal representation from other racial and ethnic groups. Grandfathers were also excluded, even though male birth parents benefit from parent training (Sanders et al., 2014). The sample was also skewed towards CGMs with higher education levels, which may reflect the study’s association with universities. Yet, in contrast to prior intervention research with small and geographically restricted samples of grandfamilies (McLaughlin et al, 2017), the generalizability of the present study is enhanced by a large sample recruited across four states.

This RCT builds upon earlier work validating the relevance of the FSM to custodial grandfamilies (Smith et al., 2018) and is the first rigorous theory-grounded attempt at comparing multiple interventions to enhance the psychological well-being of CGM and CGC alike. Our finding that BPT and CBT were superior to IOC at lessening CGM distress, improving CGM parenting practices, and reducing CGC psychological difficulties is consistent with the basic principle of the FSM that the impact of caregivers’ distress on children’s outcomes is primarily indirect through the quality of their parenting (Conger et al., 2002). Our findings also reinforce the assertion that “because psychological states are comprised of interacting cognitive, affective, behavioral, and physiological elements, any treatment which effectively targets one of these systems may lead to a change in all of them” (Mah & Johnson, 2008, p. 231). Future research is needed to determine the exact pathways through which these changes occur, as well as to identify which custodial grandfamilies benefit the most from these and other evidenced-based interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work reported on in this article was funded by a grant awarded to the first and second authors by the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR012256) and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01389726

Footnotes

Early findings of this study were presented at the 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America and the 2015 Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association

Contributor Information

Gregory C. Smith, Kent State University

Bert Hayslip, Jr., University of North Texas, Denton

Gregory R. Hancock, University of Maryland, College Park

Frederick H. Strieder, University of Maryland, Baltimore

Julian Montoro-Rodriguez, University of North Carolina, Charlotte.

References

- Beach SR, Kogan SM, Brody GH, Chen Y, Lei M, Murry VM. Change in caregiver depression as a function of the strong African American families program. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:241–252. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.241. doi:10:1037/a0013562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw B, Emery G. Cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Schrader SS. Parent-child relations. Research Instruments in Social Gerontology. 1982;2:115–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bruss GS, Gruenberg AM, Goldstein RD, Barber JP. Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale interview guide: Joint interview and test-rested methods for interrater reliability. Psychiatry Research. 1994;53:191–202. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid J. Parent observation and report of child symptoms. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chaco A, Jensen S, Lowry L, Cornwell M, Chimklis A, Chan E, Lee D, Pulgarin B. Engagement in behavioral parent training: Review of the literature and implications for practice. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2016;19:204–215. doi: 10.1007/s10567-016-0205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley CS, Caldwell MS, Flynn M, Dupre AJ, Rudolph KD. Parenting and mental health. In: Hoghughi M, Long N, editors. Handbook of parenting: Theory and research for practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 276–285. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5:314–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Analyzing structural equation models with missing data. In: Hancock GR, Mueller RO, editors. Structural equation modeling: A second course. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing; 2013. pp. 493–519. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, McGee J, Krisztal E, Kaye J, Coon D, Thompson L. Coping with care giving: Reducing stress and improving the quality of your life (Leader Version) Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson PA. Intergenerational parenting from the perspective of African American grandmothers. Family Relations. 2005;54:280–397. doi:0.1111/j.0197-6664.2005.00022.x. [Google Scholar]

- Glass JC, Huneycutt T. Grandparents parenting grandchildren: Extent of situation, issues involved, and educational implications. Educational Gerontology. 2002;28:139–161. doi: 10.1080/03601270252801391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: A review. Perspectives in Clinical Research. 2011;2:109–112. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.83221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock GR. Effect size, power, and sample size determination for structured means modeling and MIMIC approaches to between-groups hypothesis testing of means on a single latent construct. Psychometrika. 2001;66:373–388. doi: 10.1007/BF02294440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock G, French B. Power analysis in structural equation modeling. In: Hancock G, Mueller R, editors. Structural equation modeling: A second course. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc; 2013. pp. 117–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hayslip B, Fruhauf C, Dolbin-MacNab M. Grandparents raising grandchildren: What have we learned over the past decade? The Gerontologist. 2017;10:1196–2008. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayslip B, Kaminski PL. Parenting the custodial grandchild: Implications for clinical practice. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Heath CL, Curtis DF, Fan W, McPherson R. The association between parenting stress, parenting self-efficacy, and the clinical significance of child ADHD symptom change following behavior therapy. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2015;46:118–129. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Research design in clinical psychology. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Parent management training: Treatment for oppositional aggressive, and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:504–515. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Langevin DJ. A framework for understanding “evidence” in prevention research and programs. Prevention Science. 2003;4:137–153. doi: 10.1023/A:1024693321963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JN. The Potential Benefits of Parenting Programs for Grandparents: Recommendations and Clinical Implications. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24:3200–3212. doi: 10.1007/s10826-0’15-0123-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JN, Sanders MR. Using consumer input to tailor evidence-based parenting interventions to the needs of grandparents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2012;21:626–636. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9514-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JN, Sanders MR. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a parenting program designed specifically for grandparents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;52:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry-Meyer L, Newman BM. An exploration of the grandparent caregiver role. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:1005–1025. doi: 10.1177/0192513X04265955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE. Screening of child behavior problems for prevention programs at school entry. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:549–559. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.63.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke LM, Prinz RJ. Measurement of parental discipline and nurturance. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:895–929. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Weis R, O’Hare E, Rubin E. Development and initial validation of the parent behavior inventory. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:534–545. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2016.1182017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Risser HJ, Lovejoy CM. A meta-analysis of parent training: Moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:86–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah JWT, Johnson EC. Parental Social Cognitions: Considerations in the acceptability of and engagement in behavioral parent training. Clinical Child Family Psychology Review. 2008;11:218–236. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquett R, Thompson L, Reiser R, Holland J, O’Hara R, Kesler S, Stepanenko A, Bibrey A, Rengifo J, Majaros A, Gallagher-Thompson D. Psychosocial predictors of treatment response to cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life depression: An exploratory study. Aging and Mental Health. 2013;17:830–838. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.791661. org/10080/13607863.2013.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin B, Ryder D, Taylor M. Effectiveness of interventions for grandparent caregivers: A systematic Review. Marriage & Family Review. 2017;53:509–531. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2016.1177631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Hami CS, Means-Christensen AJ, Stein MB. Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS) Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23:245–249. doi: 10.1002/da.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Hami CS, Means-Christensen AJ, Stein MB. Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS) Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23:245–249. doi: 10.1002/da.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak C, Heinrichs N. A comprehensive meta-analysis of triple p-positive Parenting program using hierarchical linear modeling: Effectiveness and moderating variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11:114–144. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin K, Burgess K. Parents of aggressive and withdrawn children. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 383–418. [Google Scholar]

- Rueger S, Katz R, Risser H, Lovejoy M. Relations between parental affect and parenting behaviors: A Meta-analytic review. Parenting. 2011;1:1–33. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.539503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M, Kirby J, Tellegen C, Day J. The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34:337–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Ingram A, Wolchik S, Tein J, Winslow E. Long-term effects of parenting-focused preventive interventions to promote resilience of children and adolescents. Child Development Perspectives. 2015;9:164–171. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Schoenfelder E, Wolchik S, MacKinnon D. Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:299–329. doi: 10.1146/aaaurev.psych.121208.131619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Connell A, Dishion T, Wilson M, Gardner F. Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:417–439. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC, Cichy K, Montoro-Rodriguez J. Impact of coping resources on the well-being of custodial grandmothers and grandchildren. Family Relations. 2015a;64:378–392. doi: 10.1111/fare.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC, Merchant W, Hayslip B, Hancock G, Strieder F, Montoro-Rodriguez J. Measuring the parenting practices of custodial grandmothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015b;24:3676–3689. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0176-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G, Hayslip B, Hancock G, Merchant W, Montoro-Rodriguez J, Strieder F. The family stress model as it applies to custodial grandfamilies: A cross validation. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018;27:505–521. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0896-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G, Palmieri P. Risk for psychological difficulties in children raised by custodial grandparents. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1303–1310. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.10.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC, Strieder F, Greenberg P, Hayslip B, Montoro-Rodriguez J. Patterns of enrollment and engagement of custodial grandmothers in a randomized clinical of psychoeducational interventions. Family Relations. 2016;65:369–386. doi: 10.1111/fare.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahler RG, Cartor PG, Fleischman J, Lambert W. The impact of synthesis teaching and parent training with mothers of conduct-disordered children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:425–440. doi: 10.1007/BF01261602. doi: https://10.1007/BF0126102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JBW. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric. 1988. Structured Interview Guide for the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (SIGMA) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.