Abstract

Preterm infants are at risk for delays in motor, perceptual, and cognitive development. While research has shown preterm infants may exhibit learning delays in the first months of life, these delays are commonly under-diagnosed. The purpose of this study was to longitudinally evaluate behavioral performance and learning in two means-end problem-solving tasks for 30 infants born preterm (PT) and 23 born full-term (FT). Infants were assessed at 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months-old in tasks that required towel pulling or turntable rotation to obtain a distant object. PT infants performed more non–goal-directed and less goal-directed behavior than FT infants throughout the study, resulting in a lower success rate among PT infants. PT infants showed delayed emergence of intentionality (prevalence of goal-directed behaviors) compared to FT infants in both tasks. Amount and variability of behavioral performance significantly correlated with task success differentially across age. The learning differences documented between PT and FT infants suggest means-end problem-solving tasks may be useful for the early detection of learning delays. The identification of behaviors associated with learning and success across age may be used to guide interventions aimed at advancing early learning for infants at risk.

Keywords: infant, preterm, means-end problem solving, exploration, learning

1. Introduction

Means-end problem solving entails the execution of an intentional sequence of actions performed on a means object to achieve a goal related to an end object, such as pulling a cloth or string to obtain a distant supported or connected object (Rat-Fischer, O’Regan, & Fagard, 2014; Willatts, 1984, 1999) or using a hook/rake to surround and retrieve a distant object (Fagard, Rat-Fischer, & O’Regan, 2014). Successful means-end problem solving requires not only appropriate sensorimotor abilities and motor-perceptual coupling (Case-Smith, Bigsby, & Clutter, 1998; Gibson & Pick, 2000; Lobo & Galloway, 2008; Thelen, 1990), but also cognitive abilities, such as differentiation between the means and end object, choosing the correct action sequence, and understanding causal relations (Bremner, 2000; Bonawitz et al., 2010; Lobo & Galloway, 2008, 2013; Piaget, 1953; Sommerville & Woodward, 2005). The development of means-end problem solving is foundational for future social, cognitive, and linguistic development (Brandone, 2015; Csibra & Gergely, 2007). It might serve as a model for understanding mechanisms of early learning (Bonawitz et al., 2010; Bremner, 2000; Gibson & Pick, 2000; Lobo & Galloway, 2008; Willatts, 1999). In addition, means-end tasks may effectively identify early and persistent learning differences, and may thus serve as convenient and effective diagnostic tools to identify learning impairments earlier than they might be identified by other tools (Clearfield, Stanger, & Jenne, 2015; Lobo & Galloway, 2013).

1.1. Development of means-end problem solving in full-term infants

Typically developing infants succeed in one-step means-end tasks at 6–8 months, in two-step tasks at 9 months, and in three-step tasks at 10 months of age (Clearfield et al., 2015; Lobo & Galloway, 2008; Willatts, 1984, 1999). For example, infants pull a cloth to retrieve a distant, supported object at 7–8 months (Willatts, 1984, 1999) and use a hook to bring a distant toy within reach at 10–12 months (Clearfield et al., 2015; Fagard et al., 2014). Means-end problem-solving development continues throughout the second year as infants learn to solve more complex tasks and transfer their knowledge across contexts (Brown, 1990; Piaget, 1953). The majority of previous research on means-end problem-solving has been cross-sectional or has covered only short age periods (e.g. 3 months). Only one recent study (Babik et al., in review) assessed means-end problem solving longitudinally in full-term (FT) infants from 6- to 24-months of age in two means-end tasks: pulling a towel or rotating a turntable to retrieve a distant supported toy. With age, infants increased their performance of goal-directed behaviors and decreased performance of non–goal-directed behaviors. Task success was associated with the performance of more goal-directed behaviors. Success rate increased with age, with earlier emergence of intentionality, defined as a prevalence of goal-directed behaviors, in the towel task compared to the more demanding turntable task (6.9 vs. 10.8 months). This study, however, comprehensively reported problem-solving development only for typically developing infants.

1.2. Development of means-end problem solving in infants born preterm

Preterm birth occurs when infants are born well before the expected 40 weeks of gestational age (“moderate to late preterm” 32–37 weeks, “very preterm” 28–32 weeks, “extremely preterm” before 28 weeks). Infants born preterm (PT) are at risk for early sensorimotor impairments related to visual tracking, fixation, and visuo-manual coordination (Atkinson & Braddick, 2007; Petkovic, Chokron, & Fagard, 2016a), grasping, bimanual coordination, and object exploration (Bos, van Braeckel, & Hitzert, 2013; Grönqvist, Strand-Brodd, & von Hofsten, 2011; Lobo, Kokkoni, Cunha, & Galloway, 2015), as well as motor coordination and postural control (de Groot, 2000; van der Fits, Flikweert, Stremmelaar, Martijn, & Hadders-Algra, 1999). As sensorimotor development is an important facilitator for early learning, PT infants are also at risk for delays in learning, problem solving, and cognitive development (Cherkes-Julkowski, 1998; Heathcock, Bhat, Lobo, & Galloway, 2004; Jongbloed-Pereboom, Janssen, Steenbberg, & Nijhuis-van der Saden, 2012; Lobo & Galloway, 2013).

Previous research has demonstrated that prematurity might negatively impact infants’ problem-solving development (Lobo & Galloway, 2013; Petkovic, Rat-Fischer, & Fagard, 2016b; Sun, Mohay, & O’Callaghan, 2009). Lobo and Galloway (2013) showed that infants born before 32 weeks gestation had poorer learning at 3–4 months compared to full-term infants in an exploratory learning task involving learning to kick to move an overhead toy. These learning differences persisted through the second year of life in a means-end task involving pushing buttons to activate a distant toy. Furthermore, infants’ success rates in these learning tasks were stronger predictors of cognitive delays at 24-months than was a standardized assessment performed at the same times.

Sun et al. (2009) identified delays in means-end problem solving among 8-month olds, with high-risk PT infants showing the least, low-risk PT infants showing higher, and FT infants showing the highest level of intention. Petkovic et al. (2016b) showed that while late PT infants with typical muscle tone did not have trouble using a rake to obtain an out-of-reach object at 15–17 months, very PT infants with hypotonia were unsuccessful in this task even at 23 months. In line with dynamic systems theory, early sensorimotor exploration impairments might limit the types of behaviors infants perform with objects, restricting information gathering, and thus concatenating into means-end problem solving and overall cognitive delays for PT infants (Thelen, 2000; Thelen & Smith, 1994).

1.3. The role of amount and variability of object exploration in cognitive development

Object exploration involves sensorimotor interaction with objects and information gathering that can facilitate learning (Gibson, 1988; Rochat, 1989; Ruff, 1984). Exploratory behaviors for typical infants at 5 months has been positively related to intellectual functioning at 4 and 10 years of age, as well as to academic achievement at 10 and 14 years (Bornstein, Hahn, & Suwalsky, 2013). PT infants have been shown to perform a lower amount and variability of exploration and less multimodal exploration compared to FT infants (Lobo et al., 2015). Reduced engagement in variable, multimodal exploration may result in impoverished information gathering and suboptimal learning (Bahrick, Lickliter, & Flom, 2004; Needham, Barrett, & Peterman, 2002; Wilcox, Woods, Chapa, & McCurry, 2007). For instance, very PT infants spent less time orally and manually exploring objects compared to FT infants at 6 months, with the amount of oral and manual exploration at this age positively related to language and cognition at 24 months (Zuccarini et al., 2017). Similarly, for PT infants, delayed object exploration at 7 months related to poorer cognitive outcomes at 24 months (Ruff, McCarton, Kurtzberg, & Vaughan, 1984).

When it comes to learning, it may not only be important that infants engage in an ample amount of exploratory behaviors, but also that these behaviors be variable (Babik, Galloway, & Lobo, 2017; Dusing & Harbourne, 2010; Hadders-Algra, 2000; Lobo et al., 2015). Variability is considered a hallmark of typical development and an essential component in the development of movement ability (Touwen, 1978; Piek, 2002). Emergent abilities are characterized by greater variability (Hadders-Algra, 2000) that allows infants to explore a variety of possible actions and outcomes (Piek, 2002; Sporns & Edelman, 1993). This process gradually leads to a decrease in variability as infants continually select more effective behavioral patterns and solutions (Hadders-Algra, 2000). Therefore, reduced variability at later stages of learning may represent increased proficiency (Piek, 2002), whereas at earlier stages it may suggest impaired development (Prechtl, 1990; Sporns & Edelman, 1993). For example, PT infants showed less variability in their early spontaneous movements (Babik et al., 2017; Dusing & Harbourne, 2010; Prechtl, 1990) and object exploration behaviors (Lobo et al., 2015), which might result in decreased opportunities for information gathering and learning (Gibson, 1988; Hadders-Algra, 2000; Lobo & Galloway, 2013). Thus, the amount and variability of exploration may both be important in the development of problem solving and cognition.

1.4. Aims of the current study

Means-end problem solving is an important ability, yet its development hasn’t been comprehensively studied. Previous means-end problem-solving research has typically been cross-sectional, covered short periods of time, focused primarily on trial outcome (successful/unsuccessful), and in most cases included only typical infants. The purpose of the present study was to comprehensively and longitudinally evaluate and compare behavioral performance and learning between FT and PT infants throughout the first two years of life in two means-end tasks that involved a similar concept (object support), but required different actions (pulling vs. rotating) to achieve the task goal of retrieving a toy. We aimed to: 1) identify differences in behavioral performance in the means-end tasks between FT and PT infants; 2) identify differences in learning in the means-end tasks between FT and PT infants; and 3) determine whether the amount or variability of early object exploration would relate to learning/success in the means-end tasks.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Sample size calculation was performed using GLIMMPSE 2.2.5 (Kreidler at al., 2013). Estimated sample size based on pilot data equaled 20 participants per group, using 0.05 Type I error rate and 0.8 target power.

Fifty-three infants participated in this study: 30 PT 10 males (≤32 weeks gestational age, Mean = 26.7, SD = 0.3 weeks of gestational age), 23 FT (13 males; Mean = 39.4, SD = 1.1 weeks gestational age). The sample was 56.4% Caucasian, 30.9% African-American, 12.7% Asian, and 9.1% Hispanic (additional sample characteristics in Table 1). Recruitment of participants, informed consent, and data collection were completed in accordance with the regulations set by the University of Delaware’s and Christiana Care Health System’s Institutional Review Boards. Participants received monetary compensation for their participation in the study. Data on FT participants have been reported elsewhere (Babik et al., in review). The analyses included in this manuscript have not been previously published.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic and health-related information (Mean±SD).

| Criteria | Infants born full-term |

Infants preterm |

born |

|---|---|---|---|

| African-American | 20.8% | 36.7% | |

| Caucasian | 70.9% | 46.7% | |

| Asian | 8.3% | 16.6% | |

| Hispanic | 0% | 13.3% | |

|

| |||

| Gross household income $0–14,999 | 4.2% | 16.7% | |

| Gross household income $15,000–24,999 | 0% | 16.7% | |

| Gross household income $25,000–34,999 | 4.2% | 0.0% | |

| Gross household income $35,000–44,999 | 4.2% | 10% | |

| Gross household income $45,000–59,999 | 8.3% | 10% | |

| Gross household income $60,000–79,999 | 25% | 20% | |

| Gross household income greater than $80,000 | 54.1% | 26.7% | |

| Mean PIR (poverty income ratio) | 2.8 | 2.3 | |

|

| |||

| Maternal education – less than high school | 4.3% | 7.1% | |

| Maternal education – completed high school | 8.7% | 32.1% | |

| Maternal education – more than high school | 87.0% | 60.7% | |

|

| |||

| Weeks preterm | 0.6±1.1 | 13.2±1.7 | |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3366.7±651.2 | 921.9±265.4 | |

| Multiple gestation | 0% | 30% | |

| Conceived via in vitro fertilization | 0% | 6.7% | |

| Weeks in neonatal intensive care unit | 0.2±0.5 | 12.3±5.4 | |

| Weeks on ventilation | 0 | 4.9±10.5 | |

| Grade III-IV intraventricular hemmorhage | 0% | 13.3% | |

| Periventricular leukomalacia | 0% | 20% | |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 0% | 13.3% | |

| Chronic lung disease | 0% | 46.7% | |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 0% | 100% | |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 0% | 63.3% | |

| Sepsis | 4% | 43.3% | |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | 0% | 53.3% | |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 0% | 50% | |

| Receiving early intervention services during the study | 0% | 50% | |

2.2. Procedures

Participants were assessed in their homes at 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months of age (corrected age for PT infants) by a trained researcher with expertise in child development. At each assessment, infants participated in two means-end tasks: 1) towel task, and 2) turntable task.

The means-end towel task (Figure 1A) assessed infants’ ability to pull a towel (means object) to obtain a distant supported toy (end object). Infants were seated in a high chair or on their parent’s lap at a table. Testing consisted of three trials in which a toy was placed beyond the infant’s reach at the far end of a folded towel. The toy was selected from a small pool of interesting toys that were consistent across all participants. The researcher attempted to attract the infants’ attention to the toy by touching it and saying “Get the toy” at the beginning of each trial. Each trial ended when an infant touched the toy, dropped the towel, or 30 seconds elapsed (see Willatts, 1999). The procedure was identical at each age.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for the means-end towel (A) and turntable (B) tasks.

The means-end turntable task (Figure 1B) assessed infants’ ability to spin a turntable (means object) to retrieve a distant supported toy (end object). The procedure was similar to that for the means-end towel task, except a turntable was used instead of a towel and the turntable was secured in place to prevent displacement.

Assessments were recorded using two synchronized camcorders providing frontal and side views of each infant. Infants’ behaviors were coded using OpenSHAPA software.

2.3. Measures

Each trial was classified as Successful or Unsuccessful. A Successful trial involved toy contact with visual attention to the toy within 5 s prior to contact (see Willatts, 1999); otherwise a trial was Unsuccessful.

All behaviors were classified as goal-directed or non–goal-directed. Goal-directed behaviors were ones that could potentially lead to attainment of the goal (end object), whereas non–goal-directed behaviors were ones that were unlikely to result in goal attainment.

For the towel task, the goal-directed behaviors were: 1) Looking at the toy: eyes directed towards toy; 2) Pulling the towel: pulling or sliding the towel in any direction on the surface. Non–goal-directed behaviors were: 1) Looking at the towel: eyes directed towards the towel; 2) Touching the towel: hand(s) statically touching or feeling the towel, but not moving it; 3) Lifting the towel: lifting at least half of the towel without pulling it; 4) Mouthing the towel: mouth, tongue, or lips in contact with the towel; 5) Reaching for the distant toy: extending the arm(s) for the out-of-reach toy. Filemaker Pro Advanced custom programs (Filemaker, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) were used to convert the coded data to percent of trial time by dividing the cumulative duration of a behavior during a trial by the total duration of the trial.

For the turntable task, the goal-directed behaviors were: 1) Looking at the toy: eyes directed towards the toy; 2) Alternate spinning of the turntable: spinning the turntable in alternating directions; 3) Unidirectional spinning of the turntable: spinning the turntable continuously in one direction. Non–goal-directed behaviors were: 1) Looking at the turntable: eyes directed towards the turntable; 2) Touching the turntable: hand(s) statically touching or feeling the turntable, but not moving it; 3) Pulling the turntable: attempting to pull, slide, or push the turntable on the surface; 4) Banging the turntable: hand cyclically hitting the turntable; 5) Mouthing the turntable: mouth, tongue, or lips in contact with the turntable; 6) Reaching for the distant toy: extending arm(s) for the out-of-reach toy.

For analyses related to the amount and variability of exploration, three new variables were calculated: 1) Amount of exploration: percent of trial time the infant engaged in any of the coded behaviors; 2) Variability of exploration: percent of all behaviors (goal-directed and non– goal-directed) performed at each visit relative to the total number of behaviors observed across the entire sample for the task; 3) Cumulative success rate: percent of successful trials out of the total number of trials completed throughout the study.

Coders were blind to participants’ birth status. Intra-rater agreement was 95.7±1.5% and inter-rater agreement with a primary coder was 90.3±5.2% for 20% of the coded data based on the equation [Agreed/(Agreed+Disagreed)]*100.

2.4. Statistical analyses

To ensure that the observed effects in the current study were not only statistically significant, but also meaningful, effect sizes are reported using Cohen’s d (0.2 small, 0.5 medium, 0.8 large, 1.2 very large) calculated from t-test statistics (Cohen, 1988). Results with p≤.05 are reported as statistically significant.

2.4.1. Initial Analyses

To examine potential differences in sex and socioeconomic composition between the FT and PT samples: 1) an independent-samples t-test related infants’ Birth Status to family income and poverty income ratio (PIR, ratio of household income to the poverty level specific to the family composition and geographic area; Karlamangla, Merkin, Crimmins, & Seeman, 2010); 2) a chi-square test of independence related infants’ Birth Status to sex (0 = males; 1 = females), maternal education (0 = less than high school; 1 = completed high school; 2 = more than high school; Karlamangla et al., 2010), and a maternal socioeconomic status (SES) index [0 = low SES (maternal education less than high school and PIR<2); 2 = high SES (maternal education more than high school and PIR≥2); 1 = middle SES (all others; Karlamangla et al., 2010)]. Previous research found that maternal education is a better (Mercy & Steelman, 1982) or equally good predictor (Scarr & Weinberg, 1978) of children’s cognitive development than is paternal education.

To better understand factors affecting infants’ success in the two means-end tasks, we related the Cumulative success rate in each task to infants’ sex and presence of brain injury at birth (0 = no brain injury; 1 = brain injury) using an independent-samples t-test, and to infants’ birth weight (in grams) and gestational age (in days) using regression analyses (first for the entire sample of FT and PT infants to represent a broad range of gestational age and birth weight, and then only for PT group to comply with previous research). These analyses included data for both FT and PT infants to represent a broad range of gestational ages and birth weights. Also, infants’ birth weight and gestational age were correlated using bivariate Pearson two-tailed correlation. These analyses were performed using SPSS.

2.4.2. Behavioral performance in the means-end tasks for FT and PT infants

For these analyses, Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling Software (HLM; Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2004) was used. HLM is the most appropriate and recommended technique for longitudinal designs, allowing for a hierarchical data structure in which observations across age are nested within participants, thus accounting for non-independence of multiple observations for each participant. In all HLM models, linear and quadratic trends of change with age were tested using Age and Age2 variables. Age by Birth Status (0 = preterm; 1 = full-term) variable interaction terms (Age* Birth Status and (Age)2 *Birth Status) were included in the models to address the extent to which growth trajectories differed between FT and PT infants. Non-significant trends and random effects were dropped from the final models via backward elimination starting with the higher-order interaction terms.

Data for the three means-end trials of each assessment were averaged within each visit for each infant. To determine whether there were differences between FT and PT infants in developmental trajectories for behaviors across age, each behavior (including aggregated Goal-directed and Non–goal-directed behaviors) was entered into HLM as a dependent variable, while Birth Status, Age, and Age2 were entered as independent variables.

To assess the emergence of intention, we estimated the age when FT and PT infants would be expected to shift from performing mostly non–goal-directed towards predominantly goal-directed behaviors in each task by noting the time points at which estimated developmental trajectories for Goal-directed and Non–goal-directed behaviors intersected one another.

2.4.3. Learning in the means-end tasks for FT and PT infants

Difference in trial success rate across age between FT and PT infants was analyzed via raw data plots. Also, binomial logistic regression was performed using SPSS to determine the effect of birth status on the likelihood of a successful trial outcome across age. An Outcome variable specifying level of trial success (0 = Unsuccessful trial; 1 = Successful trial) was entered into the model as a dependent variable, while Birth Status and Age were entered as independent variables. To analyze differences in behaviors demonstrated by FT and PT infants during successful vs. unsuccessful trials, each behavior was entered into HLM as a dependent variable, while Outcome, Birth Status, Age, and Age2 were entered as independent variables.

2.4.4. Amount and variability of exploratory behavior in relation to means-end learning

Amount and variability of exploration in the two means-end tasks across age were compared between FT and PT infants by entering into HLM Amount of exploration and Variability of exploration as dependent variables, and Birth Status, Age, and Age2 as independent variables.

To determine whether the amount or variability of exploration at each visit related to infants’ cumulative trial success at 24 months, Amount of exploration and Variability of exploration at each visit were correlated with Cumulative success rate using bivariate Pearson two-tailed correlation. To account for multiple comparisons, Bonferroni correction (α ≤ .01) was used. For these analyses, we included data for FT and PT infants together so we could have a broad range in the amount and variability of behaviors to discover potential relations with trial success.

3. Results

3.1. Initial analyses

No statistically significant differences were found in family income levels between FT and PT infants [FT: M=$67,238.70, SD=$21,502.30; PT: M=$53,369.80, SD=$27,111.20; t(48)=−1.98, p=.054, d=0.57]. Similarly, differences in families’ poverty income ratio between the FT and PT infants were not statistically significant [FT: M=2.82, SD=1.10; PT: M=2.27, SD=1.30; t(48)=−1.56, p=.118, d=0.45]. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups in infants’ sex (χ2(1,N=53)=3.06, p=.080), maternal education (χ2(2,N=51)=4.59, p=.101), or maternal SES index (χ2(2,N=50)=3.80, p=.149). Therefore, we assumed the equivalence of the FT and PT samples on sex and SES parameters.

Infants’ cumulative success throughout 24 months in the towel task was not associated with their sex or presence of a brain injury at birth [Sex: males (M=60.82, SD=20.80), females (M=59.93, SD=22.06), t(50)=0.15, p=.883, d=0.04; Brain Injury: infants without brain injury (M=62.38, SD=20.43), infants with brain injury (M=44.81, SD=22.90), t(50)=1.96, p=.056, d=0.27]. In the turntable task, infants’ cumulative success did not relate to their brain injury status, but was significantly related to their sex, with males being more successful throughout the first 24 months than females in the turntable task1 [Brain Injury: infants without brain injury (M=41.97, SD=18.88), infants with brain injury (M=26.11, SD=19.37), t(50)=1.93, p=.059, d=0.55; Sex: males (M=45.89, SD=20.49), females (M=34.81, SD=17.09), t(50)=2.13, p=.039, d=0.60].

When relating data across the entire sample of infants, birth weight and gestational age were both related to infants’ cumulative trial success in the towel task [Weight: F(1,49)=9.70, p=.003, d=0.89; Gestational Age: F(1,50)=9.15, p=.004, d=0.86]. In the turntable task, infants’ birth weight, but not gestational age were related to their cumulative trial success [Weight: F(1,49)=8.15, p=.006, d=0.82; Gestational Age: F(1,50)=2.46, p=.123, d=0.44]. Note that infants’ birth weight and gestational age were strongly correlated (r(50)=.950, p<.0001).

When only relating data for the PT group, birth weight and gestational age were unrelated to infants’ cumulative trial success in the towel task [Weight: F(1,27)=2.10, p=.159, d=0.56; Gestational Age: F(1,27)=0.67, p=.419, d=0.32] and in the turntable task [Weight: F(1,27)=1.47, p=.235, d=0.47; Gestational Age: F(1,27)=0.02, p=.901, d=0.05]. These statistically nonsignificant findings may be due to decreased power (note the medium to large effect sizes for 3 of the 4 analyses performed) or to more limited variability within the PT sample in birth weight and gestational age compared to the full sample (Weight: 397 to 1395 grams (SD=244.2) in PT infants, 397 to 5075 grams (SD=1321.6) in full sample; Gestational Age: 23.7 to 29.7 weeks (SD=1.82) in PT infants, 23.7 to 41.1 weeks (SD=6.58) in full sample).

3.2. Behavioral performance in the means-end tasks for FT and PT infants

Lifting the towel, Mouthing the towel, and Mouthing the turntable had a high frequency of zero values (>95%) and could not be reliably analyzed individually, but were included in the analyses of aggregated behaviors.

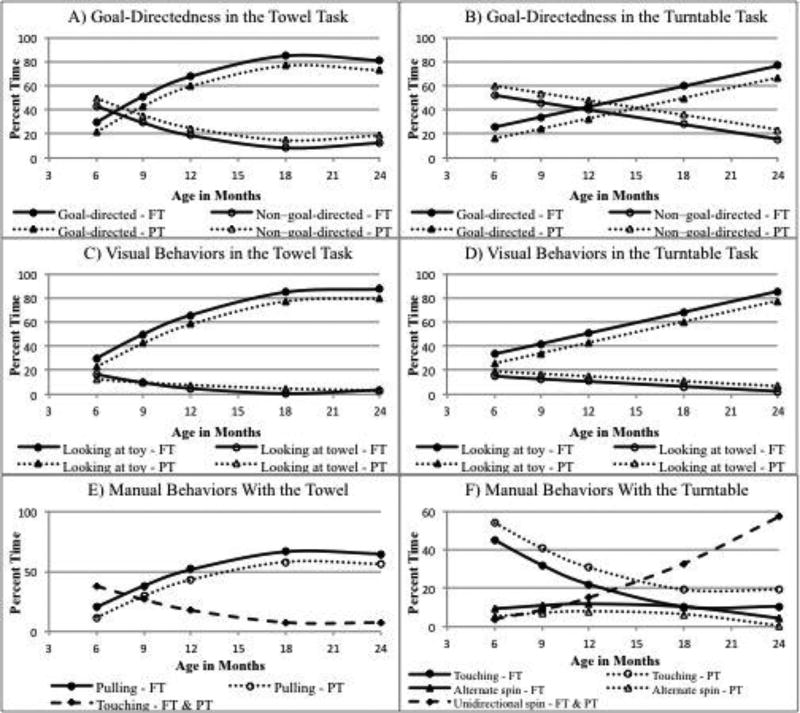

Differences in developmental trajectories of behaviors performed by FT and PT infants in the two tasks were analyzed. Detailed information on statistical parameters for the following analyses is provided in online supplementary materials Table S1. With age, all infants performed more goal-directed behavior (GDB) and less non–goal-directed behavior (NGDB) in both tasks [GDB Towel: t(195)=8.88, p<.001, d=1.27; NGDB Towel: t(195)=7.69, p<.001, d=1.10; GDB Turntable: t(193)=14.22, p<.001, d=2.05; NGDB Turntable: (t(244)=10.19, p<.001, d=1.30]. Across age, PT infants performed less goal-directed behavior and more non–goal-directed behavior than FT infants in both tasks [GDB Towel: t(51)=1.89, p=.065, d=0.53; NGDB Towel: t(51)=1.89, p=.064, d=0.53; GDB Turntable: t(51)=2.29, p=.026, d=0.64; NGDB Turntable: t(244)=2.28, p=.023, d=0.29; Figure 2A–B].

Figure 2.

Estimated growth curves for goal-directed vs. non–goal-directed behaviors in the towel (A) and turntable (B) tasks; looking behaviors in the towel (C) and turntable (D) tasks; and motor behaviors in the towel (E) and turntable (F) tasks; FT = full-term; PT = preterm.

Specifically, with age, infants decreased their looking at the means object (LMO) and increased looking at the end object (LEO) [LMO Towel task: t(193)=2.38, p=.018, d=0.34; LEO Towel task: t(195)=8.15, p<.001, d=1.17; LMO Turntable task: t(193)=5.61, p<.001, d=0.81; LEO Turntable task: t(193)=16.85, p<.001, d=2.43]. PT infants spent more time looking at the means object and less time looking at the end object than FT infants in both tasks [LMO Towel task: t(51)=2.24, p=.030, d=0.63; LEO Towel task: t(51)=1.97, p=.054, d=0.55; LMO Turntable task: t(51)=2.53, p=.014, d =0.71; LEO Turntable task: t(51)=2.13, p=.038, d=0.60; Figures 2C–D].

With age, all infants increased their performance of goal-directed towel pulling (TWP), as well as alternate (TTAS) and unidirectional (TTUS) turntable spinning [TWP: t(195)=6.27, p<.001, d=0.90; TTAS: t(243)=2.16, p=.032, d=0.28; TTUS: t(192)=1.98, p=.049, d=0.29]. PT infants performed less towel pulling and alternate turntable spinning, but did not differ from FT infants in unidirectional turntable spinning [TWP: t(51)=2.19, p=.033, d=0.61; TTAS: t(243)=1.82, p=.070, d=0.23; TTUS: t(51)=0.67, p=.504, d=0.19; Figures 2E–F]. All infants also decreased their performance of non–goal-directed towel touching (TWT), as well as turntable touching (TTT), pulling (TTP), and banging (TTB) with age [TWT: t(195)=5.84, p<.001, d=0.84; TTT: t(192)=4.46, p<.001, d=0.64; TTP: t(192)=2.80, p<.001, d=0.40; TTB: t(241)=2.82, p=. 005, d=0.36]. PT infants showed more non–goal-directed turntable touching and banging than FT infants, whereas no differences were found between groups for towel touching [TTT: t(51)=2.96, p=.005, d=0.83; TTB: t(241)=2.67, p=. 008, d=0.34; TWT: t(51)=1.54, p=.129, d=0.43; Figures 2E–F].

Estimated statistical models (Table S1) suggested that the emergence of intentionality occurred earlier in FT than in PT infants in both the towel (7.1 vs. 8.3 months; Figure 2A) and turntable task (11.5 vs. 15.1 months; Figure 2B). The gap in the timing of the emergence of intentionality between FT and PT infants was larger for the turntable task compared to the towel task (3.6 vs. 1.2 months).

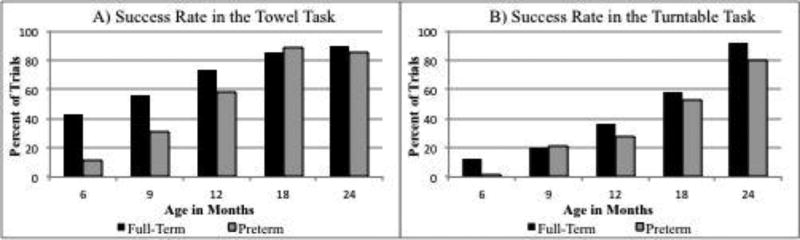

3.3. Learning in the means-end tasks for FT and PT infants

Raw data plots suggested the percent of successful trials increased with age for FT and PT infants in both tasks (Figures 3A–B). Across all visits, higher success rates were observed in the towel task than the turntable task. Success rate was generally lower for PT than FT infants across all ages in both tasks.

Figure 3.

Percent of successful trials across age in the towel (A) and turntable (B) tasks for infants born full-term vs. preterm.

The likelihood of infants’ success in the two tasks changed with age and differed between PT and FT infants. For the towel task, in the binomial logistic regression model both the Age variable (χ2(1)=184.68, p<.0001) and the Birth Status variable (χ2(1)=21.38, p<.0001) were statistically significant. The model suggested that a one-month age increase made occurrence of success 1.22 times more likely across all infants, whereas FT infants were 2.25 times more likely than PT infants to exhibit success in towel task trials. Similarly, for the turntable task, in the binomial logistic regression model both the Age variable (χ2(1)=247.08, p<.0001) and the Birth Status variable (χ2(1)=5.71, p<.017) were statistically significant. The model suggested a one-month age increase made occurrence of success 1.24 times more likely across all infants, whereas FT infants were 1.55 times more likely than PT infants to show success in turntable task trials.

Next, differences in developmental trajectories for behaviors performed by FT and PT infants during Successful vs. Unsuccessful trials were analyzed. In Successful trials, all infants performed more goal-directed and less non–goal-directed behaviors in both tasks across age [GDB Towel: t(52)=9.31, p<.001, d=2.58; NGDB Towel: t(52)=2.71, p=.009, d=0.75; GDB Turntable: t(52)=13.24, p<.001, d=3.67; NGDB Turntable: t(623)=6.06, p<.001, d=0.49; online Table S2]. More looking at the end object occurred in Successful trials in both tasks [Towel: t(52)=11.33, p<.001, d=3.14; Turntable: t(52)=8.60, p<.001, d=2.39]. There were no differences in looking at the means object between Successful and Unsuccessful trials in both tasks across age [Towel: t(52)=0.69, p=.495, d=0.19; Turntable: t(52)=0.48, p=.632, d=0.13]. Infants demonstrated more goal-directed towel pulling, as well as alternate and unidirectional turntable spinning, and less non–goal-directed towel touching and turntable touching in Successful trials [TWP: t(52)=7.73, p<.001, d=2.14; TTAS: t(52)=1.90, p=.063, d=0.40; TTUS: t(52)=10.50, p<.001, d=0.05; TWT: t(684)=2.74, p=.006, d=0.21; TTT: t(623)=6.04, p<.001, d=0.48].

Although all infants performed more goal-directed than non–goal-directed behavior during successful trials, PT infants showed less goal-directed behavior in the turntable task and more non–goal-directed behavior in both tasks compared to FT infants during Successful trials [GDB Towel: t(51)=1.21, p=.231, d=0.34; NGDB Towel: t(51)=1.91, p=.062, d=0.53; GDB Turntable: t(622)=2.07, p=.039, d=0.17; NGDB Turntable: t(51)=2.23, p=.030, d=0.62].

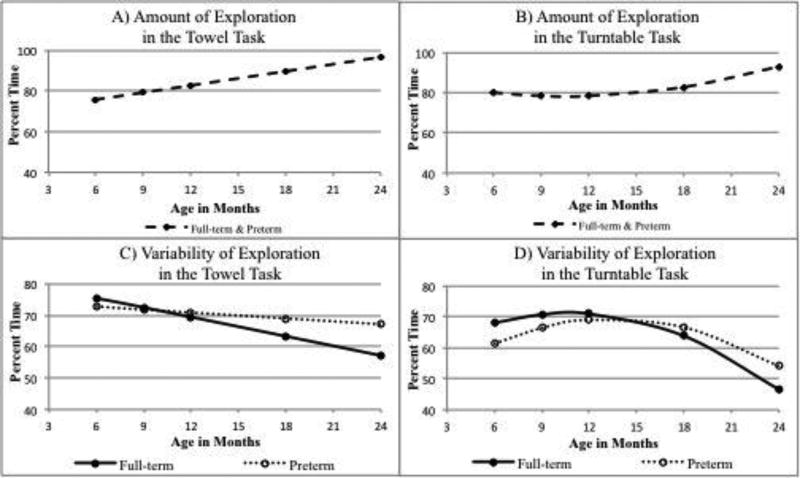

3.4. Amount and variability of exploratory behavior in relation to means-end learning

The amount and variability of exploratory behavior in the two means-end tasks across age were compared between FT and PT infants. With age, all infants increased their amount of exploration in both tasks [Towel: t(188)=6.64, p<.001, d=0.97; Turntable: t(191)=2.11, p=.036, d=0.31; online Table S3]. PT infants did not differ from FT infants in the amount of exploration across the 6 to 24 month age period in either task [Towel: t(51)=1.17, p=.248, d=0.33; Turntable: t(51)=0.66, p=.510, d=0.19; Figures 4A–B].

Figure 4.

Estimated growth curves for the amount and variability of exploration in the towel (A & C) and the turntable (B & D) tasks across age.

With age, as infants became more successful at obtaining the end object, trial durations decreased, with a quadratic trend of change, from 22.9 seconds at 6 months to 7.8 seconds at 24 months in the towel task, and from 31.4 seconds at 6 months to 16.3 seconds at 24 months in the turntable task [Age: t(441)=7.81, p<.001; Age2: t(441)=4.55, p<.001, d=0.74; Task: t(441)=12.08, p<.001, d=1.15]. Differences between PT and FT infants trended toward significance, with PT infants showing slightly longer trials throughout the study [Birth Status: t(51)=1.99, p=.052, d=0.56].

The variability of exploration decreased across age in the towel task [t(192)=2.07, p=.040, d=0.30]. In the turntable task, the variability of exploration increased until 12 months, then decreased [t(242)=3.61, p<.001, d=0.46]. FT and PT infants differed in their trajectories of exploration variability in both tasks [Towel: t(192)=2.07, p=.040, d=0.37; Turntable: t(242)=2.13, p=.035, d=0.27]. FT infants exhibited more exploration variability than PT infants until about 10 months in the towel task, and 14.6 months in the turntable task. Afterwards, the variability of exploration for FT infants was significantly lower than that of PT infants (Figures 4C–D).

Next, the amount and variability of exploration for infants in each means-end task was correlated with each infant’s cumulative trial success at 24 months (Table 2). In the towel task, the amount of exploration at 6 and 18 months, but not at other ages, was positively correlated with cumulative trial success (Table 2). In the turntable task, the amount of exploration at 6 and 12 months positively correlated with cumulative trial success. This means that more exploration at an early age of 6 months and also around 12–18 months was associated with greater trial success through 24 months in both tasks. In the towel task, the variability of exploration at 24 months negatively correlated with cumulative trial success (Table 2). In the turntable task, the variability of exploration at 18 months, but not at other ages, negatively correlated with cumulative trial success. This means that less variability around 18–24 months was associated with greater trial success through 24 months in both tasks.

Table 2.

Bivariate (two-tailed) Pearson correlations between amount or variability of exploration at each assessment and cumulative success rate through 24 months in the towel and turntable tasks;

| Infants’ age (months) |

Towel task | Turntable task |

|---|---|---|

| Amount of exploration

| ||

| 6 | r(48)=.437, p=.002* | r(46)=.391, p=.006* |

| 9 | r(49)=.281, p=.045 | r(50)=.138, p=.330 |

| 12 | r(46)=.288, p=.047 | r(49)=.482, p<.0001* |

| 18 | r(46)=.380, p=.008* | r(47)=.303, p=.034 |

| 24 | r(43)=.334, p=.025 | r(44)=.278, p=.062 |

|

| ||

| Variability of exploration

| ||

| 6 | r(48)=.087, p=.550 | r(46)=.357, p=.013 |

| 9 | r(50)=−.068, p=.633 | r(50)=.118, p=.403 |

| 12 | r(49)=−.247, p=.081 | r(49)=−.027, p=.850 |

| 18 | r(47)=−.203, p=.162 | r(47)=−.501, p<.0001* |

| 24 | r(46)=−.568, p<.0001* | r(45)=−.034, p=.819 |

significant correlations after Bonferroni correction (α≤.01).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to longitudinally and comprehensively evaluate behavioral performance and learning of means-end problem solving in infants born FT or PT in two tasks involving a similar relational construct (support) but different actions (pulling vs. rotating).

4.1. Behavioral performance of means-end problem solving may be delayed in PT infants

First, we established the equivalence between our FT and PT samples on sex and SES parameters. No statistically significant differences between the FT and PT samples were found in their sex composition, maternal education, family income, poverty income ratio, or the SES index (Karlamangla et al., 2010). Lower birth weight and gestational age were significantly related to lower success rate in both means-end tasks, which is consistent with previous research showing a strong association between low gestational age/birth weight and suboptimal motor and cognitive outcomes (de Kieviet, Piek, Aarnoudse-Moens, & Oosterlaan, 2009; Linsell, Malouf, Morris, Kurinczuk, & Marlow, 2015). Note that neither birth weight nor gestational age significantly predicted infants’ cumulative trial success within the PT group alone. This lack of statistical significance was likely due to insufficient power or variability within the PT group.

Presence of a brain injury at birth was not associated with infants’ cumulative trial success. This counter-intuitive result was likely due to the low power of this analysis, comparing 6 infants with brain injury to 47 peers without brain injury. Whereas males and females showed similar levels of success in the towel task, males had more success than females in the turntable task. One might assume that these results stem from potentially higher physical demands of the turntable task, requiring more trial-and-error activity than the towel task, and the proposal that males may exhibit higher levels of activity compared to females (e.g., Eaton & Enns, 1986). Although current results show that the turntable is cognitively, but not necessarily physically, more challenging than the towel task, no evidence of males’ higher level of activity during the turntable task was found. In contrast, current results suggest that differences in cumulative success between males and females in the turntable task might stem from males’ higher levels of visual attention to the goal rather than their amount, variability, or type of physical behavior in the task.

Current results suggested that infants displayed a variety of exploratory behaviors toward the means and end objects while problem solving in the two means-end tasks. With age, all infants increased their performance of goal-directed behavior (e.g., looking at the end object, towel pulling, alternate and unidirectional turntable spinning) and showed less non–goal-directed behavior (e.g., looking at the means object, static towel and turntable touching, and turntable pulling and banging) in both tasks. These results agree with previous research (Babik et al., in review; Willatts, 1984, 1999).

Across all ages, PT infants performed less goal-directed and more non–goal-directed behavior than FT infants in both tasks. Although previous research showed that PT infants might display delays in means-end problem solving (Lobo & Galloway, 2013; Petkovic et al., 2016b; Sun et al., 2009), nobody, to our knowledge, has analyzed the behavioral roots of those delays. We propose that PT infants may be delayed in their intentionality (shift towards performing more goal-directed behaviors than non-goal-directed behaviors) perhaps due to their delayed understanding of object properties and affordances, relations between objects, distinction between means and end objects, and/or means-end causation (Bremner, 2000; Gibson, 1988; Lobo & Galloway, 2008, 2013; Sommerville & Woodward, 2005; Sommerville, Hildebrand, & Crane, 2008; Willatts, 1999). These results represent early learning delays for PT infants in means-end tasks, with typical development being associated with higher levels of goal-directedness. Previous research suggests that these early delays may likely relate to more global future learning delays (Cherkes-Julkowski, 1998; Jongbloed-Pereboom et al., 2012; Lobo & Galloway, 2013).

The emergence of intentionality in PT infants was delayed compared to FT infants in both the towel task (8.3 vs. 7.1 months) and the turntable task (15.1 vs. 11.5 months). Similar to Babik et al. (in review), we found that intentionality emerged earlier for all infants in the towel task than in the turntable task. Current results showed that the gap in the emergence of intentionality between PT and FT infants was larger in the more demanding turntable task (3.6 months) compared to the towel task (1.2 months). This might suggest a greater window of time the turntable task could be used to identify early problem-solving delays in infants at risk.

4.2. Learning of means-end problem solving may be delayed in PT infants

Not only did infants’ behaviors in the means-end tasks become more goal-directed with age, but performance of goal-directed, rather than non–goal-directed behavior, was strongly associated with successful trial performance in both tasks across age. Whereas success rates increased with age for all infants in both tasks, PT infants were less successful than FT infants across all ages in both tasks. For example, infants born PT were 2.25 times less likely to succeed in the towel task and 1.55 times less likely to succeed in the turntable task than their FT peers.

These results echo previous research findings suggesting that PT infants might demonstrate early delays in problem solving, learning, and cognitive development (Cherkes-Julkowski, 1998; Jongbloed-Pereboom et al., 2012; Lobo & Galloway, 2013). These cognitive delays have been proposed to stem from sensorimotor impairments (Atkinson & Braddick, 2007; Petkovic et al., 2016b) that limit object exploration and information gathering (Bos et al., 2013; Grönqvist et al., 2011; Lobo et al., 2015). The current study’s focus on changes in behavioral performance across age allowed us to shed light on the roots and developmental mechanisms of delays in means-end problem solving for PT infants.

4.3. Amount and variability of exploratory behaviors in relation to means-end learning

We hypothesized that the amount of early exploration would be positively related to means-end problem-solving success (Gibson, 1988; Lobo & Galloway, 2013). With age, all infants increased the amount of exploration performed on the task objects in both means-end tasks. In addition, more exploration at the early age of 6 months, and also around 12–18 months, was associated with increased cumulative success through 24 months. These results are in line with previously reported findings showing that object exploration at 6–7 months relates to cognitive performance at 24 months (Ruff et al., 1984; Zuccarini et al., 2017). Therefore, amount of object exploration might serve as an early indicator of problem-solving ability or learning delays, with a higher amount of exploration suggesting typical development.

No statistically significant differences were found between FT and PT infants in the total amount of exploration performed in the two means-end tasks throughout the first two years of life. Ruff et al. (1984) also observed no differences in the amount of exploration between FT and PT infants, but did report significant differences between “high-risk” and “low-risk” PT infants. Similarly, Lobo et al. (2015) demonstrated that after the age of 6 months, PT infants no longer differed from FT infants in their overall amount of behavioral performance; however, they did exhibit less multimodal exploration, less variable exploration, and difficulty matching their behaviors to the properties of objects. The current results suggest the content and variability of early exploratory behaviors, rather than simply the amount of exploration, may be important for future cognitive outcomes.

Indeed, the variability of exploration was shown to decrease from 6 to 24 months in the towel task, while it increased until 11–12 months and decreased thereafter in the turntable task. FT infants showed greater behavioral variability than PT infants until the age of 10 months in the towel task and until 14.6 months in the turntable task, whereas thereafter the variability of exploration for FT infants was significantly lower than that of PT infants. We propose that engagement in a large repertoire of object exploration behaviors early in development allows infants to begin problem solving via hypothesis testing, trying behaviors, observing the consequences, and remembering action-consequence relations (Bremner, 2000; Gibson & Pick, 2000; Piaget, 1953; Touwen, 1978). This process may be delayed for infants born PT because it relies on sensorimotor abilities that have been documented to be impaired for those infants (Atkinson & Braddick, 2007; Bos et al., 2013; Lobo et al., 2015; Petkovic et al., 2016b). As infants start distinguishing ends from means, understanding means-end causation and consequences of their own actions (Lobo & Galloway, 2008; O’Connor & Russel, 2015; Sommerville et al., 2008; Sommerville & Woodward, 2005), they become adept at selecting effective motor patterns, which results in successful problem solving, thus reducing the variability of their exploratory behaviors (Hadders-Algra, 2000; Piek, 2002). We propose that while the emergence of intentionality is driven by an increase in goal-directedness, the intentionality itself triggers the “pruning” of exploratory behaviors and reduction in their variability.

We further hypothesized that the variability of exploratory behaviors would be positively related to trial success at early ages, but not at later ages (Bornstein et al., 2013; Zuccarini et al., 2017). Although we did not find a significant relation between exploration variability at early ages (6–9 months) and success rate, reduction of variability at later ages (18–24 months) was positively related to infants’ cumulative success rate through the age of 24 months. Importantly, the timing of the shift in the level of exploration variability seemed to depend on the complexity of the task. In less demanding tasks, this shift may occur earlier than in more challenging tasks. In the current study, for example, infants were already decreasing the variability of their exploratory behaviors at 6 months of age in the towel task, while this decrease did not begin until the age of 11–12 months in the more demanding turntable task. This shift may also represent infants’ transition from more sensorimotor exploration to inner experimentation, facilitated by their growing symbolic understanding. As infants acquire the ability to mentally represent objects and to remember events, action consequences, and object relations, they may be able to find solutions to problems mentally without resorting to physical trial-and-error experimentation (Piaget, 1953). In this case, the turntable task might have been more difficult because the initial action required is not one infants commonly observe or encounter or because it required more refined mental problem-solving and therefore required more physical trial-and-error experimentation than the simpler towel task.

We propose that the timing of this shift in variability of object exploration might be used as a diagnostic sign to identify early learning delays. Whereas low levels of variability may be associated with learning delays at earlier ages (Babik et al., 2017; Hadders-Algra, 2000; Lobo et al., 2015; Prechtl, 1990; Sporns & Edelman, 1993), high levels of exploration variability might serve as a sign of learning delays at later ages (Piek, 2002). While using exploration variability as a diagnostic sign of potential learning delays, however, one should carefully choose a task with appropriate difficulty level and high sensitivity to identify learning delays at a particular age. For example, while the towel task may function well for identifying learning delays among 5–7-month-old infants, the turntable task may be more appropriate for 11–13-month-olds.

4.4. Clinical Implications

PT infants are at risk for delays in perceptual, motor, and cognitive development (Atkinson & Braddick, 2007; Bos et al., 2013; Cherkes-Julkowski, 1998; de Groot, 2000; Lobo et al., 2015; Petkovic et al., 2016b). While research has shown that PT infants may exhibit learning delays during the first months of life, adequate tools for early diagnosis of such delays are lacking (Hack et al., 2005; Lobo & Galloway, 2013). This study highlighted significant delays in performance and learning of means-end problem solving in PT infants. Current results suggest that infants’ amount and variability of object exploration, as well as their development of goal-directedness in means-end tasks might serve as convenient diagnostic signs of early learning delays. Not only are means-end tasks convenient, affordable, and engaging for infants, there is a growing body of literature suggesting they are effective in identifying early and persistent learning impairments (Clearfield et al., 2015; Lobo & Galloway, 2013).

To guide the development of focused interventions aimed at minimizing possible learning delays in infants at risk, the results suggest infants should be provided frequent opportunities to actively engage in means-end learning tasks. In the early stages of learning, infants should be encouraged to explore a wide variety of behaviors with the objects involved in the task, rather than having only the “correct” solution modeled and prompted. Infants should be encouraged to attend to the end object, even when acting on the means object, so they can observe and learn about the consequences of their behaviors on the more distant end object. Later in the learning process, interventions aimed at advancing infants’ active performance of goal-oriented behaviors may help facilitate learning of means-end problem-solving concepts in infants at risk (Gibson, 1988; Lobo & Galloway, 2008, 2013; Lobo, Galloway, & Savelsbergh, 2004; O’Connor & Russel, 2015; Sommerville et al., 2008). Future studies should aim to develop and test the effectiveness of interventions that aim to positively impact infants’ means-end problem solving and learning (Harbourne et al., in press).

5. Strengths and Limitations

This study has a number of strengths. First, the longitudinal design of this study permitted a comprehensive picture of means-end problem-solving development in infancy. Although comprehensive longitudinal analyses of means-end performance and learning have been previously performed on typically developing FT infants (Babik et al., in review), the current study, to our knowledge, is the first in-depth comparison of means-end problem-solving development between infants born FT or PT. Second, previous research has covered only short periods of time (3 months), whereas the current results shed light on the development of means-end problem solving throughout the first two years of life. Third, past studies have primarily focused on infants’ trial outcome (successful/unsuccessful), while the present study provides a detailed account of the diverse behaviors infants perform in the means-end tasks. Finally, testing infants’ means-end performance across two means-end tasks with the same concept (support), but different level of complexity due to different action requirements (linear pulling vs. circular rotation), allowed us to better understand the timing and mechanisms of means-end problem-solving development in different tasks.

A limitation of the study was the heterogeneous nature of the current sample of PT infants, which included infants with diverse birth weight, some with perinatal brain injury and some without. All attempts were made to present thorough demographic and health-related information on this sample and to determine the influence of factors that might affect means-end problem solving success. On the other hand, the diversity of the current sample allowed us to highlight important aspects about means-end problem-solving development in infants with a wide range of health characteristics and abilities.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Means-end performance was assessed longitudinally for full-term and preterm infants

Preterm infants had delays in learning, behavioral performance, and intentionality

Higher amounts of exploration related to greater future success in the tasks

Behavioral variability decreased with learning and differed for preterm infants

Implications for early assessment and intervention are discussed

What this paper adds?

Preterm infants may be delayed in performance and learning of means-end problem solving throughout the first two years. Means-end tasks might help identify early learning delays. Documenting behaviors associated with learning longitudinally in problem-solving tasks can inform us how to facilitate learning for infants at risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the infants and their parents for their participation in this study. Also, we thank the support of research assistants with the coding of data. This research was supported by the National Institute of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (1R21HD076092-01A1, Lobo PI; 1R01HD051748, Galloway, PI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Finding significant differences between males and females in their cumulative success during the turntable test, we wanted to determine the source of these differences. Since trial success required a goal-directed manual behavior to co-occur with visual attention to the goal, we checked whether the performance of turntable spinning and/or looking at the toy differed significantly between males and females. Spinning of the turntable showed no significant differences between the two sexes while controlling for age (t(51)=0.92, p=.360) or not controlling for age (t(51)=1.28, p=.207). Developmental trajectories of looking at the toy across age did not differ between males and females (t(51)=1.59, p=.117), whereas on average across all ages males looked at the toy more than females (t(245)=2.00, p=.047). These results suggest that differences in cumulative success between males and females might have stemmed from differences in visual attention to the goal rather than differences in goal-oriented manual behavior.

References

- Atkinson J, Braddick O. Visual and visuocognitive development in children born very prematurely. From Action to Cognition. 2007;164:123–149. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)64007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babik I, Galloway JC, Lobo MA. Infants born preterm demonstrate impaired exploration of their bodies and surfaces throughout the first 2 years of life. Physical Therapy. 2017;97(9):915–925. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzx064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babik I, Cunha AB, Ross SM, Logan SW, Galloway JC, Lobo MA. Means-end problem solving in infancy: Development, emergence of intentionality, and transfer of knowledge. Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1002/dev.21798. (in review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrick LE, Lickliter R, Flom R. Intersensory redundancy guides the development of selective attention, perception, and cognition in infancy. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13(3):99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz EB, Ferranti D, Saxe R, Gopnik A, Meltzoff AN, Woodward J, Schulz LE. Just do it? Investigating the gap between prediction and action in toddlers’ causal inferences. Cognition. 2010;115:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn CS, Suwalsky JT. Physically developed and exploratory young infants contribute to their own long-term academic achievement. Psychological Science. 2013;24(10):1906–17. doi: 10.1177/0956797613479974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos AF, van Braeckel KNJA, Hitzert MM, Tanis JC, Roze E. Development of fine motor skills in preterm infants. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2013;55(4):1–4. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandone AC. Infants’ social and motor experience and the emerging understanding of intentional actions. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:512–523. doi: 10.1037/a0038844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JG. Developmental relationships between perception and action in infancy. Infant Behavior and Development. 2000;23(3):567–582. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL. Domain-specific principles affect learning and transfer in children. Cognitive Science. 1990;14(1):107–133. [Google Scholar]

- Case-Smith J, Bigsby R, Clutter J. Perceptual-motor coupling in the development of grasp. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998;52(2):102–110. doi: 10.5014/ajot.52.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkes-Julkowski M. Learning disability, attention-deficit disorder, and language impairment as outcomes of prematurity: A longitudinal descriptive study. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1998;31(3):294–306. doi: 10.1177/002221949803100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clearfield MW, Stanger SB, Jenne HK. Socioeconomic status (SES) affects means-end behavior across the first year. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2015;38:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Csibra G, Gergely G. “Obsessed with goals”: Functions and mechanisms of teleological interpretation of actions in humans. Acta Psychologica. 2007;124:60–78. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot L. Posture and motility in preterm infants. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2000;42(1):65–68. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kieviet JF, Piek JP, Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Oosterlaan J. Motor development in very preterm and very low-birth-weight children from birth to adolescence. JAMA. 2009;302(20):2235–2242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusing SC, Harbourne RT. Variability in postural control during infancy: implications for development, assessment, and intervention. Physical Therapy. 2010;90:1838–1849. doi: 10.2522/ptj.2010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WO, Enns LR. Sex differences in human motor activity level. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;100(1):19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard J, Rat-Fischer L, O’Regan JK. The emergence of use of a rake-like tool a longitudinal study in human infants. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:491. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson EJ. Exploratory behavior in the development of perceiving, acting, and the acquiring of knowledge. Annual Review of Psychology. 1988;39:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson EJ, Pick AD. An ecological approach to perceptual learning and development. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grönqvist H, Strand-Brodd K, von Hofsten C. Reaching strategies of very preterm infants at 8 months corrected age. Experimental Brain Research. 2011;209(2):225–233. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2538-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack M, Taylor HG, Drotar D, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Wilson-Costello, Morrow M. Poor predictive validity of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development for cognitive function of extremely low birth weight children at school age. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):333–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadders-Algra M. The Neuronal Group Selection Theory: a framework to explain variation in normal motor development. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2000;42(8):566–572. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200001067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbourne RT, Chang HJ, Dusing SC, Lobo MA, McCoy SW, Bovaird J, Babik I. Sitting Together and Reaching to Play (START-Play): Design and protocol for a multisite randomized controlled efficacy trial on intervention for infants with neuromotor disorders. Physical Therapy. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzy033. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heathcock JC, Bhat AN, Lobo MA, Galloway JC. The performance of infants born preterm and full-term in the mobile paradigm: learning and memory. Physical Therapy. 2004;84(9):808–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongbloed-Pereboom M, Janssen A, Steenbergen B, Nijhuis-vanderSanden MWG. Motor learning and working memory in children born preterm: A systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36(4):1314–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla AS, Merkin SS, Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. Socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular risk in the United States, 2001–2006. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreidler SM, Muller KE, Grunwald GK, Ringham BM, Coker-Dukowitz ZT, Sakhadeo UR, Glueck DH. GLIMMPSE: Online power computation for linear models with and without a baseline covariate. Journal of Statistical Software. 2013;54(10):i10. doi: 10.18637/jss.v054.i10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsell L, Malouf R, Morris J, Kurinczuk JJ, Marlow N. Prognostic factors for poor cognitive development in children born very preterm or with very low birth weight: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(12):1162–1172. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo MA, Galloway JC. Postural and object-oriented experiences advance early reaching, object exploration, and means-end behavior. Child Development. 2008;79:1869–1890. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo MA, Galloway JC. Assessment and stability of early learning abilities in preterm and full-term infants across the first two years of life. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo MA, Galloway JC, Savelsbergh GJ. General and task-related experiences affect early object interaction. Child Development. 2004;75(4):1268–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo MA, Kokkoni E, Cunha AB, Galloway JC. Infants born preterm demonstrate impaired object exploration behaviors throughout infancy and toddlerhood. Physical Therapy. 2015;95:51–64. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130584. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercy JA, Steelman LC. Familial influence on the intellectual attainment of children. American Sociological Review. 1982;47:532–542. [Google Scholar]

- Needham A, Barrett T, Peterman K. A pick-me-up for infants’ exploratory skills: Early simulated experiences reaching for objects using ‘sticky mittens’ enhances young infants’ object exploration skills. Infant Behavior and Development. 2002;25(3):279–295. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor RJ, Russell J. Understanding the effects of one's actions upon hidden objects and the development of search behaviour in 7-month-old infants. Developmental Science. 2015;18(5):824–831. doi: 10.1111/desc.12265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkovic M, Chokron S, Fagard J. Visuo-manual coordination in preterm infants without neurological impairments. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016a;3:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkovic M, Rat-Fischer L, Fagard J. The emergence of tool use in preterm infants. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016b;7:267. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. The origin of intelligence in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Piek JP. The role of variability in early motor development. Infant Behavior and Development. 2002;25(4):452–465. [Google Scholar]

- Prechtl HFR. Qualitative changes of spontaneous movements in fetus and preterm infant are a marker of neurological dysfunction. Early Human Development. 1990;23:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(90)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rat-Fischer L, O’Regan JK, Fagard J. Comparison of active and purely visual performance in a multiple-string means-end task in infants. Cognition. 2014;133(1):304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R, du Toit M. HLM 6: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rochat P. Object manipulation and exploration in 2- to 5-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25(6):871–884. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff HA. Infants’ manipulative exploration of objects: Effects of age and object characteristics. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff HA, McCarton C, Kurtzberg D, Vaughan HG. Preterm infants’ manipulative exploration of objects. Child Development. 1984;55:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, Weinberg RA. The influence of “family background” on intellectual attainment. American Sociological Review. 1978;43:674–692. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville JA, Hildebrand EA, Crane CC. Experience matters: The impact of doing versus watching on infants’ subsequent perception of tool use events. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(5):1249–1256. doi: 10.1037/a0012296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville JA, Woodward AL. Pulling out the intentional structure of action: The relation between action processing and action production in infancy. Cognition. 2005;95(1):1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporns O, Edelman GM. Solving Bernstein’s problem: A proposal for the development of coordinated movement by selection. Child Development. 1993;64:960–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Mohay H, O'Callaghan M. A comparison of executive function in very preterm and term infants at 8 months corrected age. Early Human Development. 2009;85:4. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E. Coupling perception and action in the development of skill: A dynamic approach. In: Bloch H, Berthenthal BI, editors. Sensory-motor organizations and development in infancy and early childhood. Boston: Kluwer Academic; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E. Grounded in the world: Developmental origins of the embodied mind. Infancy. 2000;1(1):3–28. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0101_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E, Smith LB. A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Touwen BCL. Variability and stereotypy in normal and deviant development. In: Apley J, editor. Care of the Handicapped Child. Clinics in Developmental Medicine No. 67. London: Heinemann Medical Books; 1978. pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- van der fits IB, Flikweert ER, Stremmelaar EF, Martijn A, Hadders-Algra M. Development of postural adjustments during reaching in preterm infants. Pediatric Research. 1999;46(1):1–7. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox T, Woods R, Chapa C, McCurry S. Multisensory exploration and object individuation in infancy. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(2):479–495. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willatts P. The stage-IV infants solution of problems requiring the use of supports. Infant Behavior and Development. 1984;7:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Willatts P. Development of means-end behavior in young infants: Pulling a support to retrieve a distant object. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:651–667. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccarini M, Guarini A, Savini S, Sansavini A, Iverson JM, Aureli T, Faldella G. Object exploration in extremely preterm infants between 6 and 9 months and relation to cognitive and language development at 24 months. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2017;68:140–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.