Abstract

Background

We aim to quantify the relationship between age, pretreatment comorbidity and survival outcomes in patients with locally-advanced larynx cancer.

Methods

Baseline comorbidity data were collected and age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was calculated for each case. Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazards modeling were used to determine associations with survival.

Results

For 548 patients, with median age of 59 years (range 31–91), 58% were treated with larynx preservation and the rest with total laryngectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy. 238 patients (43%) had at least one comorbidity. Cardiovascular diseases were the most common comorbidity (19%). 5-yr overall survival (OS) for patients with CCI≤3 (n=442) were superior to CCI>3(n=106) (60%vs.41%, P< 0.0001), though 5-yr disease-specific survival (DSS) were not significantly different. 5-yr non-cancer cause specific survival (NCCSS) was better for age-adjusted CCI≤3 (88%vs.67%, P< 0.0001).

Conclusions

The age-adjusted CCI is a significant predictor of NCCSS and OS for locally-advanced larynx cancer patients, but is not associated with DSS.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Larynx cancer, radiotherapy, Comorbidity, Age, survival outcomes

Introduction

Pre-existing medical comorbidities present additional challenges for older patients suffering from head and neck cancer, where a significant proportion of patients have also been users of tobacco and alcohol. These patients are at a greater risk for cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses in addition to the development of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in the aerodigestive tract.(1–6) Up to 65% of patients with head and neck cancer are afflicted with clinically relevant pretreatment comorbidities.(3, 5, 7, 8)

While there have been many advances in surgical larynx preservation strategies, advances in chemotherapy and radiotherapy have led to a shift from surgery to laryngeal preservation therapy in the treatment of advanced laryngeal carcinomas.(9, 10) Patients treated for laryngeal SCC may enjoy better survival outcomes, as compared to other tobacco-driven, e.g. oral cavity cancers, making them more susceptible to competing causes of death from comorbidities and other factors.(1–3, 5, 11)

Comorbidities have been shown to play a significant role in many aspects of care in elderly patients suffering from cancer, including treatment selection, response to therapy, tumor progression, morbidity, and survival outcomes. Multiple studies have demonstrated that pretreatment comorbidity status is an independent predictor of overall survival (OS).(1–9, 11–13)

Selective studies have elaborated on the timing of competing mortalities, establishing a specific time point where head and neck cancer mortality risk is overtaken by the risk of non-cancer-cause mortality.(1, 2, 11, 12, 14) However, to our knowledge, no study has described this time point in patients with locally-advanced laryngeal SCC. To this end, the primary aim of this study is to characterize the association between age and/or pretreatment comorbidity with survival outcomes for patients with locally advanced larynx SCC.(13, 15) Furthermore, we aim to explore the effect of age and/or comorbidities per each treatment strategy, as well as establish a specific time point where laryngeal cancer mortality risk is exceeded the risk of non-cancer-cause mortality.

Materials & Methods

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by The University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Institutional Review Board. Patients with confirmed pathological diagnosis of laryngeal SCC between 1985 and 2011 were reviewed. Selection criteria were: patients with previously untreated locally advanced disease (as classified by the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] staging manual published in 2010); complete records describing pretreatment medical history; and definitive treatment received at our institution. For each patient, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status scores, tumor sub-site location, clinical TNM staging data, and staging findings from computed tomography (CT) and/or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT imaging were obtained and recorded. For patients who underwent surgery as their primary treatment, pathological tumor staging characteristics were included. Chemotherapy regimen(s) and timing with regards to radiotherapy (induction, concurrent, or both) were recorded, along with radiation dose, fractionation, beam energy, and delivery technique. Cause of death was manually coded with patients having active cancer at time of death were coded as a “cancer-related death,” and patients without active disease at last follow up were coded as a “non-cancer-related death.”

Comorbidity assessment

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to obtain and evaluate comorbidity data from our patient population. The CCI was originally developed in 1987 to characterize and quantify the prognostic effect of comorbidities in patients with breast cancer. The scores were created with regard to their weighted overall mortality risk.(16) The CCI has since been validated in the head and neck cancer population by Singh et al who described its utility and ease of use in the setting of retrospective studies.(17) Also, the age-adjusted CCI was calculated by adding one point to the CCI score for every decade over the 40’s.(18) Age-adjusted CCI has recently been validated in the nasopharyngeal carcinoma patient population.(19)

Survival Endpoints

The Kaplan Meier product limit method was used to calculate (from date of diagnosis) 5- and 10-year overall survival, disease-specific survival (DSS; defined as death from larynx cancer coded as an event, with all others censored), non-cancer cause-specific survival (NCCSS; where all deaths recorded in patients without active cancer at the time of last follow up were coded as events, with all others censored). NCCSS was used as a crude estimator of non-cancer mortality events. These variables were calculated for the total number of patients as well as patients in each treatment cohort: surgery (total or partial laryngectomy) plus adjuvant therapy (TL-PORT), larynx preservation therapy with induction and/or concurrent chemoradiotherapy (LP-CRT), larynx preservation therapy with definitive radiation alone (LP-RT).

Statistical Analysis

Competing risk of death was implemented using Weibull parametric fitting using cause of death as a competing risk variable for uncensored data. Initial univariable Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to determine the correlation of the following variables with survival outcomes: age, CCI score, age-adjusted CCI score, ECOG performance status, sex, T stage (T3 vs. T4), nodal status (N0 vs. N+), tumor subsite (glottic vs. supra/sub glottic), treatment cohort (surgery vs. laryngeal preservation [including both LP plus chemoradiation and LP plus radiation alone groups]), and chemotherapy (any chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy). Continuous variables which demonstrated a significant association with an outcome in initial analysis were then subjected to recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) to identify appropriate cutoff thresholds and subsequently converted to binary levels based on the resultant thresholds. The converted binary variables as well as nominal variables with P<0.1 were included in a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model.

For comparison of model performance when adding age, CCI, or age-adjusted CCI to the base model without age or comorbidity information, we used Bayesian information criterion (BIC). A lower BIC indicates improved model performance and parsimony, using the BIC evidence grades presented by Raftery(20) with the posterior probability of superiority of a lower BIC model based on the difference of tested model and the base model. Per Raftery(20), a BIC difference of <2 is considered “Weak”, 2–6 denoted “Positive”, 6–10 as “Strong”, and >10, “Very strong”.

Survival distributions between various groups were compared with log-rank test. Data were analyzed using JMP 11.2 Pro statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and statistical significance was determined using a specified non–Bonferroni-corrected α of 0.05.

Results

Patient and Treatment Characteristics

A total of 633 patients with previously untreated T3 or T4 squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx presented to our institution during the defined study period. Of these, 85 patients were excluded due to unspecified comorbidity data, leaving 548 patients for analysis. The median follow up for living patients was 77 months (interquartile range “IQR” 47–143). The median age at diagnosis was 59 years (IQR 52–66), and 406 patients (74%) were men. The vast majority (95%) were smokers. Of the 318 patients (58%) who were treated using the laryngeal preservation approach, 206 (65%) received induction (n=52), concurrent (n=113) or both induction and concurrent (n=41) chemotherapy. Of the 230 patients (42%) who underwent TL-PORT, 191 (83%) received radiotherapy alone followed by total laryngectomy, and 39 (17%) received induction (n=7), concurrent (n=28) or both induction and concurrent (n=4) chemotherapy. Of the entire study population, 104 patients (19%) received induction chemotherapy (induction only n=59, induction plus concurrent n=45). Of these patients, 55% received platinum plus taxane-based regimens (n=57) and 40% received platinum based regimens (n=42). Patient and disease characteristics, and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1. At last follow up, 144 patients (26%) were alive, 176 (32%) had documented cancer-related death, 168 (31%) died with no evidence of cancer, 16 (3%) died of second primary cancer, 17 (3%) died of unknown cause, and 27 (5%) were lost to follow-up.

Table 1.

Patient, disease, and treatment Characteristics

| Laryngectomy and Adjuvant Radiotherapy |

Laryngeal Preservation | |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| No. of patients | 230 | 318 |

| Median age in years (range) | 58 (32–91) | 61 (33–88) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 180 (78) | 226 (71) |

| Female | 50 (22) | 92 (29) |

| CCI | ||

| 0 | 136 (59) | 174 (54) |

| ≥1 | 94 (41) | 144 (46) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0–1 | 205 (89) | 291 (92) |

| 2–3 | 25 (11) | 27 (8) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 142 (62) | 233 (73) |

| African American | 47 (20) | 38 (12) |

| Hispanic | 39 (17) | 36 (11) |

| Others | 2 (1) | 11 (4) |

| Subsite | ||

| Glottic | 38 (17) | 58 (18) |

| Supra/trans/sub Glottic | 192 (83) | 260 (82) |

| T stage | ||

| T3 | 91 (40) | 264 (83) |

| T4 | 139 (60) | 54 (17) |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 80 (35) | 162 (51) |

| N1 | 45 (20) | 45 (14) |

| N2a | 8 (3) | 8 (2) |

| N2b | 41 (18) | 40 (13) |

| N2c | 43 (19) | 51 (16) |

| N3 | 13 (5) | 12 (4) |

| Chemotherapy sequence | ||

| Induction | 7 (3) | 52 (16) |

| Concurrent | 28 (12) | 113 (36) |

| Induction plus concurrent | 4 (2) | 41 (13) |

| None | 191 (83) | 112 (35) |

| Total radiation dose (Gy) | mean 60.20 ± SD 5.1 | mean 71.75 ± SD 3.4 |

| No. of fractions received | mean 31.48 ± SD 4.4 | mean 43.66 ± SD 14.0 |

| Radiotherapy technique | ||

| 2D/3D conformal | 180 (78) | 230 (72) |

| IMRT | 50 (22) | 88 (28) |

Comorbidity Characteristics

A total of 238 patients (43%) suffered from at least one comorbid condition prior to the start of therapy. The most common types of comorbidities recorded were cardiovascular which affected 19% of the population (n=102) and respiratory which affected 18% of the population (n=98). When stratified by treatment strategy, higher proportion of patients in the LP-RT group had pretreatment comorbidities (i.e. CCI score ≥1) when compared to both the LP-CRT group (56% vs. 39%, P = 0.004) and the TL-PORT group (56% vs. 41%, P = 0.007). A detailed summary of patient comorbidity characteristics can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comorbidity Characteristics

| Type of Comorbidity | No of patients |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 102 |

| Respiratory | 98 |

| Endocrine | 56 |

| Gastrointestinal | 34 |

| Immunological | 5 |

| Cognitive | 3 |

| Musculoskeletal | 1 |

| Genitourinary | 1 |

| Previous tumor (within 5 years) | 34 |

| None | 310 |

Age, Comorbidity and Survival

Univariable analysis of overall survival demonstrated that older age (P<.0001), higher CCI score (P=.01), higher age-adjusted CCI score (P<.0001), higher ECOG performance status (P=.001), supra/trans-glottic subsites (P=.001), and nodal positive disease (P<.0001) were all associated with worse OS. RPA driven cutoff points associated with worse OS were identified for age ≥ 64 years, CCI score > 1, age-adjusted CCI score > 3, and ECOG performance status > 1. A baseline initial multivariable model that included disease subsite, ECOG performance status, N stage, and treatment variables revealed disease subsite, ECOG performance status, and N stage variables were independent correlates of OS with model BIC of 4070 as shown in table 3. The addition of either age or age adjusted-CCI to the baseline model achieved equal improvement of model performance with BIC reduction >10 in both, while the addition of non-age adjusted CCI score achieved positive but less substantial reduction of BIC (Table 3).

Table 3.

Uni- and multi-variable analysis of overall survival.

| Characteristics | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) |

P | HR (95% CI) |

P | BIC | ||

| Age | <64 years | 1 | 1 | 4057B | ||

| ≥64 years | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | 0.0001* | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | 0.0001* | ||

| CCI | 0–1 | 1 | 1 | 4067C | ||

| >1 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.01* | 1.3 (0.99–1.65) | 0.06 | ||

| Age-adjusted CCI | ≤3 | 1 | 1 | 4057D | ||

| >3 | 1.8 (1.4–2.4) | 0.0001* | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | 0.0001* | ||

| Sex | Male | 1 | - | |||

| Female | 1.02 (0.8–1.3) | 0.8 | - | - | ||

| Race | Caucasian | 1 | - | |||

| Non-Caucasian | 0.97 (0.8–1.2) | 0.8 | - | - | ||

| Subsite | Glottic | 1 | 1 | 4070A | ||

| Supra/trans/sub Glottic | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 0.001* | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 0.008* | ||

| T stage | T3 | 1 | - | |||

| T4 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.3 | - | - | ||

| N stage | N0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N1–N3 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 0.0001* | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 0.0003* | ||

| ECOG PS | 0–1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2–3 | 1.9 (1.3–2.6) | 0.001* | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.006* | ||

| Chemotherapy | Yes | 1 | 1 | |||

| No | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 0.14 | 1.2 (09–1.5) | 0.2 | ||

| Surgery | LP | 1 | 1 | |||

| TL-PORT | 1.05 (0.9–1.3) | 0.6 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.3 | ||

| Radiation technique | IMRT | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2D/3D CRT | 1.06 (0.8–1.4) | 0.66 | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.2 | ||

Univariable analysis of NCCSS showed age ≥ 64 years (HR 2.2; 95% CI 1.6–3.1, P <.0001), CCI score > 1 (HR 1.9; 95% CI 1.3–2.7, P =.0009), age-adjusted CCI score > 3 (HR 3.0; 95% CI 2.0–4.2, P <.0001), and ECOG performance status > 1 (HR 2.7; 95% CI 1.6–4.4, P =.0004) were significantly associated with worse NCCSS. In multivariable analysis, the addition of age-adjusted CCI achieved the lowest BIC when combined with ECOG performance status and treatment variables with >10 BIC reduction compared with the next best model that included age instead of age-adjusted CCI.

Univariable analysis of DSS showed supra/trans-glottic subsites (HR 1.5; 95% CI 1.01–2.4, P =.04), T4 (HR 1.5; 95% CI 1.1–2.0, P =.01), nodal positive disease (HR 2.4; 95% CI 1.8–3.4, P <.0001), TL-PORT (HR 1.6; 95% CI 1.2–2.1, P =.003), and no chemotherapy (HR 1.4; 95% CI 1.0–1.8, P =.04) were significantly associated with worse DSS. In multivariable analysis, nodal positive disease (HR 2.5; 95% CI 1.8–3.5, P <.0001) was the single independent significant associate of worse DSS.

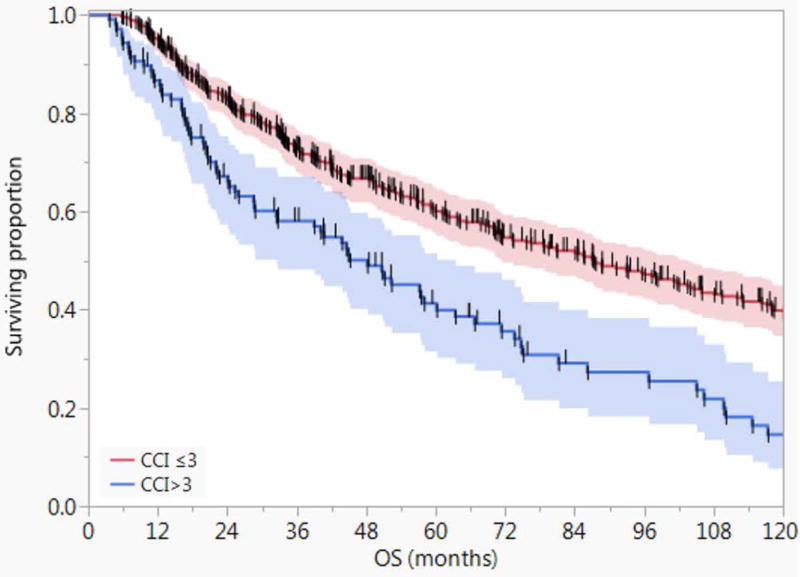

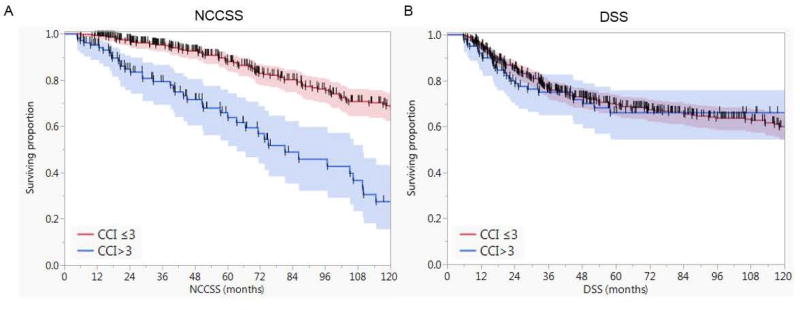

Figure 1 depicts the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with age-adjusted CCI >3 (n=106) compared with those with ≤3 (n=442) with 5- and 10-year OS of 60% and 39% versus 41% and 15%, respectively (Log-Rank P<.0001). Patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 had better 5-year and 10-year non-cancer cause specific survival (NCCSS) as well (88% and 67% vs. 64% and 25%, P <.0001). However, there was no statistically significant difference between age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 and age-adjusted CCI > 3 with regards to disease-specific survival (DSS) at 5 and 10 years (69% and 59% vs. 64% and 64%, P = 0.6) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the overall survival (OS) for patients with age-adjusted CCI >3 (n=106) compared with those with ≤3 (n=442) with 5- and 10-year OS of 60% and 39% versus 41% and 15%, respectively (Log-Rank P<.0001). Shaded colors represent 95% confidence intervals, and short vertical lines represent censored data.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing A) the non-cancer cause specific survival (NCCSS) for patients with age-adjusted CCI >3 compared with those with ≤3 and B) the disease specific survival (DSS) for both cohorts. Shaded colors represent 95% confidence intervals, and short vertical lines represent censored data.

Treatment Cohorts

In the surgery cohort (TL-PORT), 196 (85%) patients had an age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3, and 35 (15%) had an age-adjusted CCI > 3. The 5-year and 10-year OS were better for patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 compared to age-adjusted CCI > 3 (55% and 38% vs. 42% and 19%, P = 0.04). The 5-year and 10-year NCCSS were also better for patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 (88% and 72% vs. 62% and 28%, P < 0.0001). There was no statistical significant difference between age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 and age-adjusted CCI > 3 with regards to disease-specific survival (DSS) at 5 and 10 years (63% and 52% vs. 68% and 68%, (P = 0.7).

In the LP-CRT cohort, 162 (79%) patients had an age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3, and 44 (21%) had an age-adjusted CCI > 3. The 5-year and 10-year OS were better for patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 compared to age-adjusted CCI > 3 (67% and 49% vs. 54% and 14%, P = 0.0009). The 5-year and 10-year NCCSS were also better for patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 compared to age-adjusted CCI > 3 (90% and 72% vs. 72% and 21%, P < 0.0001). There was no statistical significant difference between age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 and age-adjusted CCI > 3 with regards to disease-specific survival (DSS) at 5 and 10 years (75% and 68% vs. 76% and 76%, P = 0.8).

In the LP-RT cohort, 84 (75%) patients had an age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3, and 28 (25%) had an age-adjusted CCI > 3. The 5-year and 10-year OS were better for patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 compared to age-adjusted CCI > 3 (58% and 31% vs. 23% and 9%, P = 0.0007). The 5-year and 10-year NCCSS were also better for patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 compared to age-adjusted CCI > 3 (82% and 52% vs. 52% and 26%, P = 0.04). The 5-year and 10-year DSS were better for patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 compared to age-adjusted CCI > 3 (71% and 60% vs. 41% and 41%, P = 0.03). Supplementary Table S1 summarizes all studied survival endpoints by age-adjusted CCI and treatment cohort.

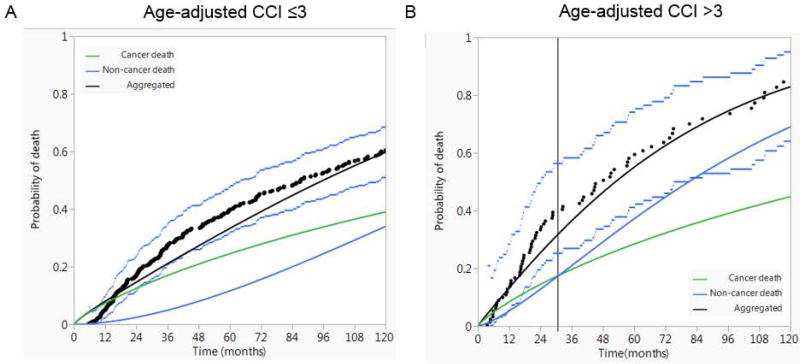

Competing Risk of Death

Competing risk of death analysis showed that the risk of non-cancer death exceeded the risk of cancer-attributed death approximately two and half years post-treatment for patients with age-adjusted CCI > 3; while non-cancer risk of demise never exceeded cancer-specific risk during the entire follow-up period for patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤ 3 as shown in figure 3. The same analysis was implemented for patients by age groups independent of comorbidity status. Patients older than 64 years had a higher cancer-attributed risk of death for 68 month after treatment while patients younger than 64 years had a higher cancer-attributed risk of death for the entire follow-up period.

Figure 3.

Competing risk of death analysis for patients with age-adjusted CCI ≤3 (A) compared with patients with age-adjusted CCI >3 (B) total laryngectomy followed by post-operative radiotherapy (TL-PORT). Black dots represent aggregated data points and dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Patients undergoing treatment for squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx that is a tobacco-driven cancer often have the additional burden of pre-existing medical comorbidities often sequelae of smoking that are compounded by greater exposure as can be seen in older patients. The current study is the first to suggest that a quantified age-adjusted CCI score of more than three appears to be of unique prognostic importance. In our series of larynx SCC patients, we demonstrate worse overall survival in patients older than 64 years and equivalently in patients with age-adjusted CCI score of greater than three. The same finding held true for patients concerning non-cancer cause-specific survival but with the age-adjusted CCI score as the strongest driver of non-cancer related mortality compared with age or non-adjusted CCI. However, neither age nor comorbidities were associated with cancer-related mortality while the nodal status was the only independent correlate of cancer-related mortality. These findings were consistent throughout the all three cohorts: surgery (TL-PORT), LP-CRT, and LP-RT.

These findings demonstrate, not surprisingly, that older patients with more comorbidities present before the initiation of therapy do worse in terms of overall survival and death from non-cancer causes when compared to their counterparts. Interestingly, in competing risk analysis for overall survival, we found that patients with an age-adjusted CCI > 3 have non-cancer mortality risk greater than that of cancer-related death fairly soon after treatment relative to the persistently higher cancer-related mortality risk in the other cohort with ≤3. This data confirms that in older patients with multiple comorbidities in the setting of advanced-stage laryngeal SCC, the risk of cancer-related death is major and should be considered in multidisciplinary treatment decision.

Previous studies reporting pretreatment comorbidity as a correlate of survival in head and neck cancer consistently showed patients with higher comorbidities had worse survival outcomes.(1–3, 8, 11, 14) The majority of these studies reported the impact of comorbidities in mixed stages and subsites of head and neck cancer. Bahig et al(21) recently reported a series of 129 patients ≥70 years with locally advanced head and neck cancers, mainly oropharyngeal in origin. The study showed the CCI≥3 was predictive of cancer-related mortality. It also showed, matching with our finding, that for this group of patients have a greater non-cancer related mortality after 3 years from treatment. Few studies, however, reported the impact of age and comorbidities on survival of laryngeal cancer patients.(4–7) Paleri et al demonstrated that moderate and severe comorbidity have a greater and statistically significant impact on survival than the TNM staging in a series of 180 patients with laryngeal SCC.(7) In a surgically treated cohort of 231 laryngeal cancer patients, severe comorbidity was associated with higher mortality particularly in early stages.(4) A single study by Sabin et al showed that adding age to the comorbidity index, reclassified 18% of the 152 patients included in their study from low- to high-grade comorbidity. But, in contrast to our results, incorporating age as an additional comorbid condition did not improve the prognostic ability of the CCI.(6) The current study, however, examined the prognostic impact of age and comorbidities in a uniform cohort of T3–T4 laryngeal SCC. We demonstrated, matching with data reported in previous studies, that both age and comorbidities are strong prognostic factors in locally advanced larynx cancer independent of treatment modality due to the high impact of both factors on non-cancer related competing mortality risk.

Our study is not without limitations. This is a retrospective patient chart review spanning three decades of patient evaluation and treatment. Due to the nature of medical record keeping systems, both electronic and paper medical records were reviewed, creating the potential for inconsistent record keeping regarding patients’ comorbidity status. For example, electronic medical records tend to be more thorough when describing a patient’s symptoms and medical comorbidities, which can affect how a patient’s CCI score was calculated. Additionally, the act of assigning patients a CCI score has the potential for error in and of itself. While the CCI scoring system has specific rules and guidelines, there is some level of subjectivity involved in assigning CCI scores to individual patients based on a retrospective review of a patient’s chart, including errors and inconsistencies in medical record keeping. Nevertheless, this is to our knowledge the largest curated advanced-stage laryngeal SCC dataset that includes detailed treatment information, patient demographic information, and CCI scores. Our study based on this unique dataset is the largest-scale analysis of its kind in the United States.

Furthermore, our findings have demonstrated that a simple clinical tool like the age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index could be of a significant prognostic impact. Since patients with scores higher than three, can be old patients with few comorbidities or relatively younger with multiple comorbidities. Therefore, we recommend the routine calculation of this index in clinics to be considered in multidisciplinary treatment decisions as well as for post-treatment surveillance programs. We also recommend using this tool to stratify patients with locally advanced laryngeal SCC in future clinical trials. We believe that while cancer related death remains the most imminent threat for patients with locally advanced laryngeal SCC and requires aggressive treatment to reduce its risk, non-cancer related death appears to be a very significant hazard in patients with high age-adjusted CCI scores and requires future strategies to personalize treatment/follow-up plans for these patients in order to improve the overall survival.

In conclusion, our findings clearly demonstrate the impact that age and pre-treatment comorbidities can have on survival outcomes in the setting of advanced-stage laryngeal cancer. The age-adjusted CCI is a significant predictor of NCCSS and OS but is not associated with DSS. After approximately 2.5 years following treatment, patients with age-adjusted CCI > 3 have non-cancer mortality risk greater than that of cancer-related death. We maintain that aggressive treatment approaches are important, but must be weighed against competing risks, and that comorbidity status be factored into treatment selection decisions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Disclosure

Drs. Lai, Mohamed, and Fuller receive funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (1R01DE025248–01/R56DE025248–01). Dr. Fuller is a Sabin Family Foundation Fellow and receives grant and/or salary support from the NIH/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Head and Neck Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) Developmental Research Program Award (P50CA097007–10) and Paul Calabresi Clinical Oncology Program Award (K12 CA088084–06); the National Science Foundation (NSF), Division of Mathematical Sciences, Joint NIH/NSF Initiative on Quantitative Approaches to Biomedical Big Data (QUBBD) Grant (NSF 1557679); the NCI QUBBD (1R01CA225190-01); the NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Early Stage Development of Technologies in Biomedical Computing, Informatics, and Big Data Science Award (1R01CA214825-01); NCI Early Phase Clinical Trials in Imaging and Image-Guided Interventions Program (1R01CA218148-01); a General Electric Healthcare/MD Anderson Center for Advanced Biomedical Imaging In-Kind Award; an Elekta AB/MD Anderson Department of Radiation Oncology Seed Grant; the Center for Radiation Oncology Research (CROR) at MD Anderson Cancer Center Seed Grant; and the MD Anderson Institutional Research Grant (IRG) Program. Dr. Fuller has received speaker travel funding from Elekta AB. Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Center Support (Core) Grant CA016672 to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Co-author specific contributions:

- Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work;

- Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content;

- Final approval of the version to be published;

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.Specific additional individual cooperative effort contributions to study/manuscript design/execution/interpretation, in addition to all criteria above are listed as follows:CFM and ASRM-Drafted initial manuscript, undertook supervised analysis and interpretation of data.AK- Assisted in data collection, tabulation, and supervised analysis and interpretation of data.KH-Co-investigator; assisted with concept inception, direct and final oversight of toxicity and clinical data collection.ASRM- Co-investigator; Supervised and undertook direct data analysis; assisted with manuscript construction and final approval; direct oversight of trainee personnel (CFM).AG and DV- Statisticians that undertook the statistical analysis component of the study.RSW, SYL, GBG, MZ, WHM, RF, ASG - Direct patient care provision, direct toxicity assessment and clinical data collection; interpretation and analytic support.DIR and CDF- Co-corresponding author; co-primary investigator; conceived, coordinated, and directed all study activities, responsible for data collection, project integrity, manuscript content and editorial oversight and correspondence; direct oversight of trainee/classifed personnel.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Argiris A, Brockstein BE, Haraf DJ, et al. Competing causes of death and second primary tumors in patients with locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(6):1956–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall SF, Groome PA, Rothwell D. The impact of comorbidity on the survival of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2000;22(4):317–22. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200007)22:4<317::aid-hed1>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mell LK, Dignam JJ, Salama JK, et al. Predictors of competing mortality in advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):15–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gimeno-Hernandez J, Iglesias-Moreno MC, Gomez-Serrano M, Carricondo F, Gil-Loyzaga P, Poch-Broto J. The impact of comorbidity on the survival of patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131(8):840–6. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.564651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen AY, Matson LK, Roberts D, Goepfert H. The significance of comorbidity in advanced laryngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2001;23(7):566–72. doi: 10.1002/hed.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabin SL, Rosenfeld RM, Sundaram K, Har-el G, Lucente FE. The impact of comorbidity and age on survival with laryngeal cancer. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78(8):578, 581–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paleri V, Wight RG, Davies GR. Impact of comorbidity on the outcome of laryngeal squamous cancer. Head Neck. 2003;25(12):1019–26. doi: 10.1002/hed.10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piccirillo JF. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(4):593–602. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(24):1685–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(22):2091–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose BS, Jeong JH, Nath SK, Lu SM, Mell LK. Population-based study of competing mortality in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3503–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen W, Sakamoto N, Yang L. Cancer-specific mortality and competing mortality in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a competing risk analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(1):264–71. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3951-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuller CD, Mohamed AS, Garden AS, et al. Long-term outcomes after multidisciplinary management of T3 laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas: Improved functional outcomes and survival with modern therapeutic approaches. Head Neck. 2016 doi: 10.1002/hed.24532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon M, Roh JL, Song J, et al. Noncancer health events as a leading cause of competing mortality in advanced head and neck cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25(6):1208–1214. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal DI, Mohamed AS, Weber RS, et al. Long-term outcomes after surgical or nonsurgical initial therapy for patients with T4 squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx: A 3-decade survey. Cancer. 2015;121(10):1608–19. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh B, Bhaya M, Stern J, et al. Validation of the Charlson comorbidity index in patients with head and neck cancer: a multi-institutional study. Laryngoscope. 1997;107(11 Pt 1):1469–75. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–51. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang CC, Chen PC, Hsu CW, Chang SL, Lee CC. Validity of the age-adjusted charlson comorbidity index on clinical outcomes for patients with nasopharyngeal cancer post radiation treatment: a 5-year nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0117323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raftery A. Bayesian Model Selection in Social Research. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:111–163. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bahig H, Fortin B, Alizadeh M, et al. Predictive factors of survival and treatment tolerance in older patients treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(5):521–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.02.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.