Abstract

Objectives

Despite experiencing migration-related stress and social adversity, immigrants are less likely to experience an array of adverse behavioral and health outcomes. Guided by the healthy migrant hypothesis, which proposes that this paradox can be explained in part by selection effects, we examine the prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders among immigrants to the United States (US).

Methods

Findings are based on the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (2012–2013), a nationally representative survey of 36,309 adults in the US.

Results

Immigrants were significantly less likely than US-born individuals to meet criteria for a lifetime disorder (AOR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.57–0.71) or to report parental history of psychiatric problems. Compared to US-born individuals, the prevalence of mental disorders was not significantly different among individuals who immigrated as children; however, differences were observed for immigrants who arrived as adolescents (ages 12–17) or as adults (age 18+).

Discussion

Consistent with the healthy migrant hypothesis, immigrants are less likely to come from families with psychiatric problems, and those who migrate after childhood—when selection effects are most likely to be observed—have the lowest levels of psychiatric morbidity.

Keywords: mental health, immigrants, acculturation

Migrating from one country to another tends to bring with it a degree of stress as individuals face the task of adjusting to life in a new context and culture.1 Although migration-related stress is to be expected, scholars have cautioned against the assumption that exposure to the stresses of migration and immigrant adaptation necessarily results in psychopathology.2–3 Indeed, whereas research in Europe suggests that immigrants are at greater risk of mental illness than are non-migrant Europeans,4–7 studies conducted in the United States (US) have shown that immigrants tend to be less likely to experience anxiety, depressive, and trauma-related disorders as compared to US-born individuals.8–14 Findings from research on mental disorders are in keeping with a broader body of literature suggesting that, despite experiencing migration-related stress and social adversity, immigrants in general are less likely to experience an array of adverse behavioral and health outcomes.15–18

A number of hypotheses and theories have emerged as scholars have attempted to make sense of this rather paradoxical body of research. One particularly compelling perspective—deemed the healthy migrant hypothesis—is that the health and well-being of immigrants can be explained, in part, by selection effects.18–19 The fundamental premise of the healthy migrant hypothesis is that the process of migration is not random, but rather that individuals who are inclined to migrate, and able to do so successfully, are part of a uniquely healthy and psychologically hardy subset. Notably, the logic here is most applicable to individuals who actively decide to migrate (presumably, older adolescents and adults) and may not extend to those who immigrate as children or to refugees and asylum seekers. Although the healthy migrant hypothesis is focused on why immigrants in general tend to fare well, other theoretical frameworks focus on why some immigrants, over time, may face increased risk for adverse outcomes. For instance, acculturation theory has been used to make sense of research suggesting that greater levels of acculturation are related with increased risk for adverse behavioral/health outcomes.20 Specifically, the mechanism for increased risk is the attenuation of the protective effects of foreign birth among child immigrants who quickly and easily acquire the cultural practices and values of the receiving country.21 Taking acculturation theorizing one step further, cultural stress theory focuses on the harmful impact of negative experiences related to migration (e.g., discrimination) rather than cultural adaptation per se.22–23

Although prior epidemiologic research on mental disorders among immigrants has advanced our understanding of this important topic, a number of critical gaps remain. To begin, many studies examining mental disorders have focused on immigrants from a single global region (e.g., Asia, Latin America) or racial/ethnic group (e.g., Latinos, Caribbean Blacks). This is, of course, understandable as focusing on immigrants from a particular region or subgroup can facilitate an in-depth examination of factors that are specifically relevant to a given population. However, such an approach does not allow for global comparisons or for a systematic examination of mental disorders across multiple immigrant sending nations, thereby limiting the generalizability of findings. Second, prior studies have tended to focus on examining the prevalence of particular disorders or the presence of one or more of an array of disorders and, as a result, our understanding of comorbid conditions among immigrants remains limited. This is particularly important in light of emerging evidence underscoring the profound overlap of internalizing and other mental disorders.24 Finally, while theorizing on mental disorders and other health conditions among immigrants has made great strides in recent years, there continues to be a need to test the validity of such theorizing, particularly using data that possesses good external validity and has sufficient sample size to detect differences across subgroups.

The Present Study

Drawing from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III, 2012–2013), we aim to address the aforementioned gaps, thereby shedding new light on the healthy migrant hypothesis. That is, we draw from the most up-to-date information available on the prevalence of mental disorders among immigrants as compared to US-born Americans. Specifically, we examine an array of anxiety, bipolar, depressive, and trauma-related disorders, examine the prevalence of comorbid disorders, and test for differences in the immigrant-mental disorder link across key sociodemographic differences. Moreover, the NESARC's large and geographically diverse sample of immigrants allows us to examine the prevalence of mental disorders among immigrants from a range of global regions and the top ten immigrant sending nations to the US. Finally, we examine key parental (i.e., mother/father psychiatric history) and migration-related (i.e., age of arrival, duration the US) factors that are relevant to theories (i.e., the healthy migrant hypothesis and acculturation theory) on the immigrant health advantage.

Method

Sample and Procedures

Study findings are based on the NESARC-III data, which were collected between 2012 and 2013.25 The NESARC—a nationally representative survey of 36,309 civilian, non-institutionalized adults ages 18 and older—is one of few national studies that provides up-to-date and well-validated diagnostic assessments of an array of mental disorders (e.g., anxiety, depressive, bipolar, and trauma-related disorders), and includes a substantial number of immigrants. Utilizing a multistage cluster sampling design and oversampling minority populations, the study interviewed individuals living in all 50 states and in Washington, DC.

Data were collected through face-to-face structured psychiatric interviews. Interviewers administered the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS-5), which provides diagnoses for an array of mental disorders.26 The AUDADIS-5 has shown to have strong procedural validity27 and acceptable reliability in the assessment of mental disorders in the general population. Participants had the option of completing the NESARC-III interview in English, Spanish, Korean, Vietnamese, Mandarin, or Cantonese.

Survey Measures

Immigrant status

Immigrant status was based on the following question: “Were you born in the US?” Consistent with prior NESARC-based studies of immigrants, those responding affirmatively were classified as US-born and those reporting they were not born in the US—including individuals born in US territories (e.g., Guam, Puerto Rico, etc.)—were classified as immigrants or foreign born.11,15 Individuals reporting foreign birth were asked to report their country of birth and age of arrival in the US (which allows researchers, in conjunction with respondent age, to estimate the number of years in the US). It should be noted that, due to the nature of the survey, it was not possible to distinguish immigrants from persons born abroad to US-born parents; however, evidence suggests that only a fraction of US-citizen births (typically between 1 and 1.5%) take place outside of the US.28 NESARC-III data also preclude the classification of immigrants by type of migration (e.g., labor, family, refugee) and, therefore, all foreign-born individuals were classified into a single category.

Mental Disorders

Using the AUDADIS-V, we examined lifetime prevalence of anxiety (i.e., Generalized Anxiety, Panic, and Social and Specific Phobia Disorders), depressive (i.e., Major Depressive, Persistent Depressive [Dysthymia] disorder), bipolar (i.e., Bipolar I), and trauma-related (i.e., Posttraumatic Stress Disorder [PTSD]) disorders, with participants who met diagnostic criteria for each particular disorder coded as 1 and all others coded as 0. We also generated an “any disorder” variable (no disorders = 0, one or more disorders = 1) and examined past 12-month diagnoses in supplementary analyses. Notably, the NESARC does not gather data on schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders29; thus, our use of the term “any disorder” refers specifically to the disorders listed above and presented in Table 1. To ensure stable estimates, we examined only those disorders with a prevalence of at least 1% in the NESARC.

Table 1.

Mental Disorders among Immigrants and US-Born Americans in the United States

| US-Born (n = 29,896; 84.05%) | Immigrant (n = 6,404; 15.95%) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Lifetime | ||||||||

| DSM-5 Disorder | ||||||||

| Any Disorder | ||||||||

| No | 65.12 | (64.0–66.2) | 79.74 | (78.4–81.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 34.88 | (33.8–36.0) | 20.26 | (19.0–21.6) | 0.47 | (0.43–0.52) | 0.63 | (0.57–0.71) |

| Generalized Anxiety | ||||||||

| No | 91.62 | (91.1–92.1) | 95.99 | (95.3–96.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 8.38 | (7.9–8.9) | 4.01 | (3.4–4.7) | 0.46 | (0.38–0.55) | 0.68 | (0.54–0.86) |

| Bipolar I | ||||||||

| No | 97.77 | (97.5–98.0) | 98.72 | (98.3–99.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2.23 | (2.0–2.5) | 1.28 | (0.97–1.7) | 0.57 | (0.42–0.77) | 0.84 | (0.56–1.28) |

| Major Depressive | ||||||||

| No | 77.83 | (77.0–78.6) | 87.68 | (86.5–88.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 22.17 | (21.4–23.0) | 12.32 | (11.2–13.5) | 0.49 | (0.44–0.55) | 0.67 | (0.58–0.76) |

| Persistent Depressive (Dysthymia) | ||||||||

| No | 93.95 | (93.5–94.3) | 97.15 | (96.6–97.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 6.05 | (5.6–6.5) | 2.85 | (2.4–3.4) | 0.45 | (0.37–0.56) | 0.64 | (0.51–0.80) |

| Panic | ||||||||

| No | 94.16 | (93.7–94.5) | 98.00 | (97.5–98.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 5.84 | (5.4–6.3) | 2.00 | (1.6–2.5) | 0.33 | (0.25–0.43) | 0.51 | (0.37–0.70) |

| Social Phobia | ||||||||

| No | 95.90 | (95.5–96.2) | 98.50 | (98.1–98.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 4.10 | (3.7–4.5) | 1.50 | (1.2–1.9) | 0.35 | (0.27–0.46) | 0.58 | (0.42–0.80) |

| Specific Phobia | ||||||||

| No | 93.15 | (92.8–93.5) | 95.96 | (95.3–96.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 6.85 | (6.5–7.2) | 4.04 | (3.5–4.7) | 0.57 | (0.49–0.67) | 0.70 | (0.59–0.85) |

| Posttraumatic Stress | ||||||||

| No | 93.24 | (92.7–93.7) | 97.24 | (96.7–97.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 6.76 | (6.3–7.2) | 2.76 | (2.3–3.3) | 0.39 | (0.32–0.47) | 0.47 | (0.38–0.58) |

Note: Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, education level, marital status, region of the United States, urbanicity, and parental history of anxiety and depression. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant.

Parental History of Mental Disorders

Participants were asked to report (no = 0, yes = 1) if their "blood or natural" father and/or mother were ever depressed (i.e., "Depressed for a period of at least two weeks") and/or anxious (i.e., "Ever had a period of feeling anxious or nervous"). In both cases, survey interviewers described characteristics of depression (e.g., low mood, feelings of worthlessness, suicidal ideation, etc.) and anxiety (e.g. sustained tension/nervousness, panic attacks, posttraumatic stress, etc.).

Sociodemographic and Family History Controls

Sociodemographic variables included: age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, education level, marital status, region of the US, and urbanicity. We also controlled for parental history of anxiety and depressive disorders.

Statistical Analyses

Survey adjusted binomial logistic regression was employed to examine the association between immigrant status and mental disorders. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were considered to be statistically significant if the associated 95% confidence intervals did not cross the 1.00 threshold when controlling for sociodemographic and parental factors. Beyond assessing statistical significance, we also interpreted the magnitude, or size, of the odds ratio (small = 0.59/1.68, medium = 0.29/3.47, large = 0.15/6.71 or greater).30 For all statistical analyses, weighted prevalence estimates and standard errors were computed using Stata 15.1 SE software. This system implements a Taylor series linearization to adjust standard errors for complex survey sampling design effects, including clustered data.

Results

As shown in Table 1, controlling for sociodemographic factors and parental history of mental disorders, immigrants were significantly less likely than US-born individuals to meet criteria for one or more lifetime disorder (AOR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.57–0.71). With the exception of bipolar disorder, this pattern of results was observed for all disorders examined with the largest associations found for PTSD (AOR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.38–0.58) and panic disorder (AOR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.37–0.70). Supplementary analyses (not shown) revealed a very similar pattern of results for past-year disorders with immigrants less likely to meet criteria for one or more disorders (AOR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.61–0.78) and, with the exception of bipolar disorder, significantly less likely to meet criteria for all disorders examined.

Analyses in Table 1 adjusted for sociodemographic and parental factors; however, this does not allow us to assess the degree to which sociodemographic factors may moderate the relationship between immigrant status and mental disorders. As such, we conducted additional analyses to test for interaction effects for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and family income with "any disorder" as the outcome variable. We found—in creating multiplicative terms with immigrant status (e.g., age*immigrant)—that the association between immigrant status and mental disorders did not significantly differ across age, gender, and race/ethnicity. However, the multiplicative term between family income and immigrant status was statistically significant (AOR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.01–1.21). Although the immigrant-disorder link was significant for all income levels, this finding suggests that the relationship is more robust among lower income individuals (family incomes less than $35,000 per year; AOR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.47–0.64) than among those residing in households with incomes between $35,000 and $69,999 (AOR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.60–0.86) or $70,000 or higher (AOR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.56–0.89).

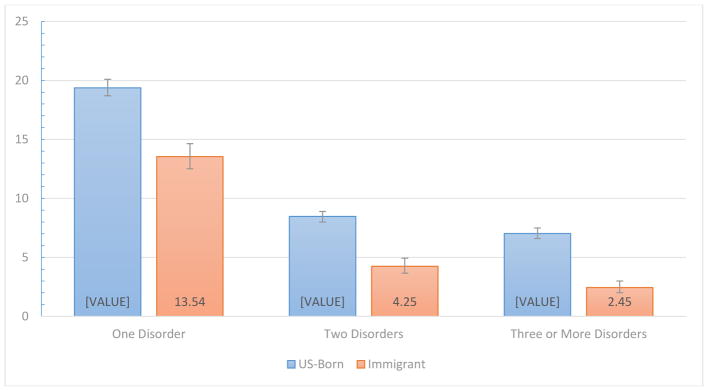

Comorbid Mental Disorders among Immigrants and US-Born

Beyond examining the association between immigrant status and individual and composite measures (i.e., met criteria for one or more disorders) of mental disorders, we also examined the prevalence of comorbidity among immigrants and US-born individuals (see Figure 1). Controlling for the same list of sociodemographic and parental confounds as in Table 1, we found that immigrants were significantly less likely than US-born individuals to meet criteria for only one disorder (AOR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.65–0.79), two disorders (AOR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.46–0.63), or three or more disorders (AOR = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.38–0.55). Supplementary analyses revealed a similar pattern of results for past 12-month diagnosis of a single (only one) and comorbid mental disorders (single disorder: AOR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.68–0.85; two disorders: AOR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.54–0.78; three or more disorders: AOR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.38–0.61).

Figure 1.

Proportion of US-born individuals and immigrants meeting criteria for lifetime mental disorders (i.e., one, two, or three or more of the following: generalized anxiety, bipolar, major depressive, dysthymia, panic, social phobia, specific phobia, or posttraumatic stress disorder). For each category, the prevalence estimates for US-born respondents are significantly greater (p < .001) compared to immigrants while controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, education level, marital status, region of the United States, urbanicity, and parental history of anxiety and depression.

Family History of Mental Disorders among Immigrants and US-Born

Table 2 presents the prevalence estimates and adjusted odds ratios contrasting the prevalence of lifetime anxiety and depressive disorders among the parents of US-born individuals and immigrants. With respect to anxiety disorders, immigrants were significantly less likely to report that their father (AOR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.71–0.91) and/or mother (AOR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.56–0.72) evidenced signs of serious anxiety, panic, post-traumatic stress or other anxiety-related problems. A similar pattern was observed, albeit with slightly larger associations, with respect to perceived parental depressive disorders. Immigrants were significantly less likely to report that their father (AOR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.48–0.62) or mother (AOR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.49–0.59) showed signs of depression in their lifetime.

Table 2.

Parental History of DSM-5 Disorders among Immigrants and US-Born Americans in the United States

| US-Born (n = 29,896; 84.05%) | Immigrant (n = 6,404; 15.95%) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Father | ||||||||

| Anxiety Disorder | ||||||||

| No | 87.60 | (86.9–88.2) | 91.55 | (90.5–92.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 12.40 | (11.8–13.1) | 8.45 | (7.5–9.5) | 0.65 | (0.58–0.74) | 0.80 | (0.71–0.91) |

| Depressive Disorder | ||||||||

| No | 83.56 | (82.8–84.3) | 91.52 | (90.8–92.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 16.44 | (15.7–17.2) | 8.48 | (7.8–9.2) | 0.47 | (0.42–0.52) | 0.55 | (0.48–0.62) |

| Mother | ||||||||

| Anxiety Disorder | ||||||||

| No | 77.85 | (77.0–78.7) | 86.34 | (85.2–87.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 22.15 | (1.3–23.0) | 13.66 | (12.6–14.8) | 0.56 | (0.50–0.61) | 0.64 | (0.56–0.72) |

| Depressive Disorder | ||||||||

| No | 71.92 | (71.1–72.7) | 84.26 | (83.2–85.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 28.08 | (27.3–28.9) | 15.74 | (14.8–16.8) | 0.48 | (0.44–0.52) | 0.54 | (0.49–0.59) |

Note: Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, education level, marital status, region of the United States, and urbanicity. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant.

The Role of Migration-Related Factors

We display, in Table 3, results of analyses testing for variation in the immigrant-mental disorder link across migration-related differences. Controlling for sociodemographic and parental factors, we found that child immigrants were not significantly different from US-born individuals in terms of lifetime mental disorders; however, immigrants who arrived as adolescents (ages 12–17; AOR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.52–0.83) and as adults (ages 18 or older; AOR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.47–0.60) were significantly less likely than US-born individuals to have met criteria for a lifetime disorder. Individuals immigrating as adolescents (AOR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.51–0.87) or as adults (AOR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.45–0.66) were also significantly less likely than those immigrating as children to have met criteria for lifetime disorder. Supplemental analyses revealed a very similar pattern with respect to past-year mental disorder diagnoses.

Table 3.

Testing Variation in the Immigrant-Disorder Link across Migration-Related Differences

| One or More Disorders | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | AOR | (95% CI) | |

| Full Sample | ||||||

| Age of Arrival | ||||||

| US-Born | 34.88 | (33.8–36.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Childhood (11 or younger) | 30.20 | (26.9–33.7) | 0.81 | (0.68–0.95) | 0.97 | (0.82–1.15) |

| Adolescence (ages 12–17) | 20.99 | (17.6–24.9) | 0.50 | (0.39–0.62) | 0.66 | (0.52–0.83) |

| Adulthood (18 or older) | 17.51 | (16.1–19.0) | 0.40 | (0.35–0.44) | 0.53 | (0.47–0.60) |

| Duration in United States | ||||||

| US-Born | 34.88 | (33.8–36.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Fewer than 10 Years | 17.70 | (15.7–19.8) | 0.40 | (0.35–0.46) | 0.54 | (0.46–0.64) |

| 10 Years or More | 21.20 | (19.6–22.8) | 0.50 | (0.45–0.56) | 0.67 | (0.59–0.75) |

| Immigrants Only | ||||||

| Age of Arrival | ||||||

| Childhood (11 or younger) | 30.20 | (26.9–33.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Adolescence (ages 12–17) | 20.99 | (17.6–24.9) | 0.61 | (0.47–0.80) | 0.67 | (0.51–0.87) |

| Adulthood (18 or older) | 17.51 | (16.1–19.0) | 0.49 | (0.40–0.59) | 0.54 | (0.45–0.66) |

| Duration in United States | ||||||

| Fewer than 10 Years | 17.70 | (15.7–19.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 10 Years or More | 21.20 | (19.6–22.8) | 1.25 | (1.05–1.48) | 1.24 | (1.02–1.50) |

Note: Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, education level, marital status, region of the United States, urbanicity, and parental history of anxiety and depression. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant. The term "one or more disorders" refers to having met lifetime criteria for at least one of the disorders listed in Table 1 (i.e., generalized anxiety, bipolar, major depressive, dysthymia, panic, social phobia, specific phobia, or posttraumatic stress disorder).

In terms of duration in the US, we found that, compared to US-born individuals, immigrants who have resided in the US for fewer than 10 years (past-year disorder: AOR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.48–0.70; lifetime disorder: AOR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.46–0.64) and for 10 or more years (past-year disorder: AOR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.64–0.83; lifetime disorder: AOR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.59–0.75) were significantly less likely to have met criteria for a mental disorder. Notably, although the associations were quite small, immigrants who had spent 10 or more years in the US were, compared to their more recently-arrived counterparts, significantly more likely to report a lifetime mental disorder (AOR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.02–1.50). No significant differences between more recent and longer-term immigrants were found for past-year mental disorders. We also found that, in simultaneously examining the relationship of mental disorders with age of arrival and duration in the US, duration in the US ceased to be statistically significant. However, the association between age of arrival and lifetime mental disorders remained significant, with a similar association as in the model that did not account for duration.

Table 4 displays the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders among immigrants from major world regions vis-à-vis the US-born. Even when adjusting for a host of sociodemographic and parental confounds, we see a clear pattern in which immigrants from Africa (AOR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.41–0.92), Asia (AOR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.43–0.77), Europe (AOR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.53–0.83), and Latin America/Caribbean (AOR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.57–0.75) were significantly less likely to have met criteria for one or more disorders. We also found, with the exception of Puerto Rico, that the bivariate odds ratios for risk of mental disorders are, compared to US-born individuals, lower among immigrants from the top immigrant sending countries. Notably, however, when adjusting for sociodemographic and parental history of anxiety and depressive disorders, differences between immigrants and US-born individuals were not significant for Vietnam or for South Korea. We should note that the sample sizes for these two countries (Vietnam: n = 159; South Korea: n = 149) were among the smallest of all countries examined and that the immigrant-mental disorder association for these countries was significant at the bivariate level.

Table 4.

Mental Disorders among Immigrants by Major World Region and Origin-Country

| One or More Disorders

|

N | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | AOR | (95% CI) | ||

| World Region | |||||||

| Africa | 16.26 | (11.6–22.2) | 0.36 | (0.25–0.53) | 0.62 | (0.41–0.92) | 280 |

| Asia | 16.11 | (14.4–18.0) | 0.36 | (0.31–0.41) | 0.58 | (0.43–0.77) | 1,285 |

| Europe | 25.19 | (21.4–29.4) | 0.63 | (0.50–0.78) | 0.66 | (0.53–0.83) | 617 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 21.44 | (19.8–23.2) | 0.51 | (0.46–0.57) | 0.65 | (0.57–0.75) | |

| Origin-Country | |||||||

| Mexico | 18.06 | (16.3–20.0) | 0.41 | (0.36–0.47) | 0.50 | (0.42–0.59) | 2,035 |

| China | 15.35 | (10.9–21.2) | 0.34 | (0.23–0.50) | 0.53 | (0.33–0.83) | 243 |

| Puerto Rico | 37.90 | (29.5–47.1) | 1.14 | (0.78–1.67) | 1.16 | (0.77–1.76) | 243 |

| Philippines | 15.43 | (11.1–21.0) | 0.34 | (0.23–0.50) | 0.53 | (0.31–0.88) | 228 |

| El Salvador | 18.91 | (13.1–26.6) | 0.43 | (0.28–0.68) | 0.54 | (0.33–0.88) | 218 |

| India | 12.41 | (8.3–18.1) | 0.26 | (0.17–0.41) | 0.48 | (0.28–0.78) | 214 |

| Dominican Republic | 19.06 | (14.8–24.2) | 0.44 | (0.32–0.59) | 0.55 | (0.39–0.77) | 172 |

| Vietnam | 16.85 | (11.0–24.8) | 0.38 | (0.23–0.62) | 0.60 | (0.33–1.11) | 159 |

| Cuba | 14.81 | (8.7–24.1) | 0.32 | (0.18–0.59) | 0.43 | (0.23–0.80) | 151 |

| South Korea | 15.29 | (9.8–23.1) | 0.34 | (0.20–0.56) | 0.52 | (0.27–1.01) | 149 |

| US-Born | 34.88 | (33.8–36.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 29,896 | ||

Note: Adjusted odds ratios adjusted for age, gender race/ethnicity, household income, education level, marital status, region of the United States, urbanicity, and parental history of anxiety and depression. The reference category for world region and origin-country variables is US-born Americans (n = 29,896). The term "One or More Disorders" refers to 1 or more lifetime reports of the disorders examined in Table 1 (i.e., Generalized Anxiety, Bipolar, Major Depressive, Dysthymia, Panic, Social Phobia, Specific Phobia, Posttraumatic Stress). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant.

Discussion

Findings from the present study, drawing from a national survey sponsored, designed and directed by the National Institutes of Health, provide clear and up-to-date evidence that immigrants are less likely than US-born individuals to experience an array of mental disorders. Controlling for key sociodemographic and parental psychiatric history confounds, immigrants were found to be less likely to meet past-year and lifetime diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety, major depressive, persistent depressive (dysthymia), panic, social/specific phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Indeed, the only exception to this pattern of findings was bipolar disorder, which has a strong genetic component31 with heritability estimates as high as 85%32 (by contrast, heritability estimates for major depression and panic disorder are closer to 40%).33–34 Beyond examining particular disorders and composite measures of "any disorder", we also found that immigrants met criteria for comorbid mental disorders at markedly lower rates than those born in the US. Simply, the evidence is clear that immigrants are, on the whole, far less likely than the US-born to experience a number of anxiety, depressive, and trauma-related disorders.

Theoretical Insights: Migration and Mental Health

Selection and the Healthy Migrant Hypothesis

Our results provide insight with respect to theories of relevance to the mental health of immigrants. The healthy migrant hypothesis posits that individuals who choose to and successfully migrate tend to be physically and psychologically healthier than non-migrants.18–19 Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that immigrants are substantially less likely than US-born individuals to report having observed serious psychiatric problems among their "blood or natural" parents. To be sure, this finding could be a reflection of higher levels of "mental health literacy" among US-born individuals35 or, potentially, a failure to measure differences in how mental disorders manifest cross-culturally36; however, it could also indicate that immigrants tend to come from families in which genetic and social risk for mental disorders is relatively low.

In addition to examining parental psychiatric history, we also tested hypotheses related to the healthy migrant hypothesis by examining differences in the prevalence of mental disorders among individuals who immigrated during childhood (age 11 or younger), adolescence (ages 12 to 17), and adulthood (age 18 or older). Within the framework of the healthy migrant hypothesis, one would expect that protective selection effects would be less applicable to child migrants—who are unlikely to be active participants the decision to migrate—than to the situation of individuals who migrate later in life (and, presumably, are more actively involved in the decision to leave their home country). Our results indicate that individuals who immigrated during adolescence or adulthood were substantially less likely than US-born individuals to have a past-year or lifetime mental disorder, but that the prevalence of mental disorders among individuals who immigrated as children was no different than that of US-born individuals. Moreover, those who migrated as adolescents and adults were significantly less likely than those who immigrated as children to have met lifetime and past-year criteria for a mental disorder.

We should be careful to note that—consistent with prior research on immigrants and health outcomes8,11—findings for migrants from Puerto Rico followed a distinct pattern from those of other foreign born populations. That is, whereas the prevalence of lifetime mental disorders among immigrants from Mexico (18%), China (15%), the Philippines (15%), El Salvador (19%), India (12%), Dominican Republic (19%) Vietnam (17%), Cuba (15%), and South Korea (15%) was found to be substantially lower than that of US-born individuals (35%), no differences were observed for Puerto Ricans (38%) in bivariate or multivariate comparisons. This is noteworthy as Puerto Ricans are distinct from other foreign born groups in several important ways. Most notably, Puerto Ricans are US citizens at birth, can travel freely to the US mainland, and can take up residence anywhere on the mainland with the benefits of citizenship (e.g., eligible for social benefits, no need for work permits), and without any of the logistical and financial exigencies of the US immigration system.37 As such, scholars have suggested that those born in Puerto Rico who reside in the US are best classified as "migrants" (rather than immigrants) or "island born" rather than "foreign born".8 These distinctions may indicate that the selection effects that are central to the healthy migrant hypothesis—namely, that significant psychological (leaving one’s country for another), and logistical barriers (gathering funds to migrate, dealing with a complex migration system) to migration lead to migrants being part of a uniquely healthy and psychologically hardy subset—are less applicable to Puerto Ricans. Indeed, Puerto Ricans can return to the island at any time, and re-migrate to the US mainland, without having to encounter the US immigration system.

Acculturation and Cultural Stress

The findings related to age of migration may also have relevance to acculturation20 and cultural stress22–23 theoretical frameworks. Acculturation theory posits that individuals who migrate early on in life (i.e., child migrants) are more likely to assimilate the cultural practices and values of the receiving society than are those who immigrate later in life. This is noteworthy as an emerging body of research suggests that greater levels of acculturation may place immigrants at risk for adverse health and behavioral outcomes.15,38 It is, therefore, plausible that the unique pattern of results with respect to child migrants may be influenced both by weaker selection effects and more accelerated acculturation processes compared to adolescent and adult migrants. Cultural stress theory may also be applicable as evidence suggests that child migrants are often targeted by their peers39 and that highly-acculturated immigrants tend to report experiencing discrimination at greater rates than their less-acculturated counterparts.38

Contrast with Findings on Migration and Mental Health Outside the US

We should be careful to note that—while consistent with prior US-based research—the overall pattern of findings from the present study stands as an important point of contrast to a robust body of research indicating that immigrants in Europe experience mental disorders at greater rates than do European-born individuals.4–7 These discordant findings raise a number of challenging questions. For instance, does this suggest something unique about the US? It could be that the US's strict and exclusionary immigration rules—which include provisions that can make entry difficult for individuals with physical and mental illness—result in an immigrant population that is, to some degree, pre-screened for mental disorders. Alternatively, it is plausible that, despite competing pro- and anti-immigrant narratives and a rapidly-changing political discourse around immigrants in the US,40 immigrants tend to experience less chronic stress in migrating to the US (a country with a long-standing history of large-scale migration)41, as compared to European nations with more limited histories of migration from beyond Europe.42 While plausible, this thesis seems tenuous, particularly in light of the well-documented levels of discrimination and negative context of reception experienced by many immigrants in the US.43 In sum, although more research is needed to understand the reasons for the divergent patterns of findings between the US and Europe, it is important to keep in mind that the pattern of lower rates of mental health problems among immigrants as compared to the native born seems to be somewhat unique to the US.

The Immigrant-Disorder Link and Household Income

The immigrant-disorder link was found to be consistent across age, gender, and race/ethnicity; however, the protective association of foreign birth was particularly robust among individuals residing in lower-income households. Although our data do not allow us to isolate those factors that may be driving this variation in effects across income level, it may be the case that divergent factors predict low-income status among immigrants versus the US born. That is, ample evidence indicates that mental health problems both lead to and are exacerbated by the challenges of low-income status in the US.44 However, this dynamic may be different among low-income immigrants (as compared to low-income non-immigrants) for several reasons. First, many low-income immigrants have limited income primarily as a reflection of limited educational opportunities and the economic challenges of migration and language limitations—not mental health.45–46 Another possible reason could be that economic hardship experienced in the US may be perceived as less stressful—and, thereby, less associated with mental health risk—by immigrants (many of whom migrate, in part, to escape even more severe economic hardship and unemployment in their home countries and/or to support family left behind in lower-income countries)47 than by US-born individuals (who may have higher expectations about their income level in the US). That being said, caution is warranted in our interpretation of these findings given that our data do not provide insight into why economic differences were observed. Further, despite the significant interaction effect we observed (i.e., income*immigrant), the immigrant-disorder link was found to be significant at all income levels; this effect was simply more robust at the lower income levels (less than $35,000 per year for total family income).

Limitations

Findings from the present study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, we were unable to account for potential self-report and cross-cultural biases relevant to the assessment of mental disorders.36,48 This is an important limitation as it is certainly plausible that immigrants may have under- or over-reported particular symptom criteria due to concerns about stigma and/or cultural differences. A second limitation is that the NESARC data do not allow us to determine whether immigrants are in the US with or without formal authorization. It is possible that authorized and unauthorized immigrants may have different mental health outcomes that we are unable to disentangle in the present study.43 A related limitation is that NESARC-III data also do not allow us to identify migration reason (e.g., labor, family) or to identify participants who are refugees/asylum seekers. Despite this limitation, refugees represent a rather small proportion of the total foreign born population in the US, as only 5–10% of the migrants arriving each year are refugees.49 Recent evidence suggests that refugees report comparable levels of major depressive disorder, and higher levels of PTSD, compared to non-refugee immigrants.50–51 Finally, although the NESARC gathers data on respondent-reported parental history of mental disorders, these data do not allow us to formally account for genetic factors that play a role in risk for mental disorders.

Conclusions

It is often assumed that the stresses of migration and immigrant adaptation result in elevated levels of mental disorders among immigrants as compared to non-migrants. Findings from the present study, however, provide compelling evidence that immigrants experience anxiety, depressive, and trauma-related disorders at substantially lower rates compared to US-born Americans. Moreover, we also found that, consistent with the healthy migrant hypothesis, immigrants are less likely to come from families marked by parental psychiatric problems and that those who migrate after childhood—when selection effects are most likely to be observed—were found to have the lowest levels of psychiatric morbidity. In terms of clinical and public health implications of the observed relationships, efforts should be made to help preserve the mental health protections experienced by immigrants, both over time and across generations. Moreover, the present results suggest that it would be beneficial to develop targeted prevention efforts, particularly for immigrants who arrive in the US during childhood.

Highlights.

Immigrants are less likely than US-born individuals to experience mental disorders.

The immigrant-disorder link was invariant across age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Immigrants are less likely to come from families with psychiatric problems.

Risk for psychiatric problems is lowest among those who migrate after age 12.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant number R25 DA030310 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through BU-CTSI Grant Number 1KL2TR001411. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Berry JW, Kim U, Minde T, Mok D. Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International migration review. 1987 Oct;1:491–511. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park Y, Kemp SP. “Little alien colonies”: Representations of immigrants and their neighborhoods in social work discourse, 1875–1924. Social Service Review. 2006 Dec;80(4):705–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suárez-Orozco C, Carhill A. Afterword: New directions in research with immigrant families and their children. New directions for child and adolescent development. 2008 Sep 1;2008(121):87–104. doi: 10.1002/cd.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mindlis I, Boffetta P. Mood disorders in first-and second-generation immigrants: systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2017 Jan 9; doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.181107. bjp-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourque F, van der Ven E, Malla A. A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first-and second-generation immigrants. Psychological medicine. 2011;41(5):897–910. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindert J, Schouler-Ocak M, Heinz A, Priebe S. Mental health, health care utilisation of migrants in Europe. European Psychiatry. 2008 Jan 1;23:14–20. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(08)70057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindert J, von Ehrenstein OS, Priebe S, Mielck A, Brähler E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social science & medicine. 2009 Jul 1;69(2):246–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alegria M, Canino G, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Nativity and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Puerto Ricans, Cuban Americans, and non-Latino Whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2006 Jan; doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alegría M, Álvarez K, DiMarzio K. Immigration and Mental Health. Current Epidemiology Reports. 2017:1-1. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s40471-017-0111-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alarcón RD, Parekh A, Wainberg ML, Duarte CS, Araya R, Oquendo MA. Hispanic immigrants in the USA: social and mental health perspectives. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 30;3(9):860–70. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breslau J, Borges G, Hagar Y, Tancredi D, Gilman S. Immigration to the USA and risk for mood and anxiety disorders: variation by origin and age at immigration. Psychological Medicine. 2009 Jul 1;39(07):1117–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salas-Wright CP, Kagotho N, Vaughn MG. Mood, anxiety, and personality disorders among first and second-generation immigrants to the United States. Psychiatry research. 2014 Dec 30;220(3):1028–36. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi DT, Zane N, Hong S, Chae DH, Gong F, Gee GC, Walton E, Sue S, Alegría M. Immigration-related factors and mental disorders among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2007 Jan;97(1):84–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams DR, Haile R, González HM, Neighbors H, Baser R, Jackson JS. The mental health of Black Caribbean immigrants: results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health. 2007 Jan;97(1):52–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanco C, Morcillo C, Alegría M, Dedios MC, Fernández-Navarro P, Regincos R, Wang S. Acculturation and drug use disorders among Hispanics in the US. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013 Feb 28;47(2):226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Schwartz SJ, Córdova D. An" immigrant paradox" for adolescent externalizing behavior? Evidence from a national sample. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2016 Jan;51(1):27–37. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1115-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, DeLisi M, Maynard BR. The immigrant paradox: Immigrants are less antisocial than native-born Americans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2014 Jul;49(7):1129. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0799-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the" salmon bias" and healthy migrant hypotheses. American Journal of Public Health. 1999 Oct;89(10):1543–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubalcava LN, Teruel GM, Thomas D, Goldman N. The healthy migrant effect: new findings from the Mexican Family Life Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2008 Jan;98(1):78–84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010 May;65(4):237. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coll CG, Marks AK. The immigrant paradox in children and adolescents: Is becoming American a developmental risk? American Psychological Association. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romero AJ, Roberts RE. Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of Mexican descent. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9(2):171–184. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Zamboanga BL, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, Romero AJ, Cano MÁ, Gonzales-Backen MA, Córdova D, Piña-Watson BM. Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects on mental health and substance use among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015 Apr 30;56(4):433–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, Meier MH, Ramrakha S, Shalev I, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science. 2014 Mar;2(2):119–37. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant BF, Amsbary M, Chu A, Sigman R, Kali J, Sugawana Y, Jiao R, Goldstein RB, Jung J, Zhang H, Chou PS. Source and Accuracy Statement: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Jung J, Zhang H, Chou SP, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Saha TD, Aivadyan C. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5): reliability of substance use and psychiatric disorder modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015 Mar 1;148:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Stohl M, Greenstein E, Aivadyan C, Morita K, Saha T, Aharonovich E, Jung J, Zhang H, Nunes EV. Procedural validity of the AUDADIS-5 depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder modules: substance abusers and others in the general population. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2015 Jul 1;152:246–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith CM. These are our numbers: Civilian Americans overseas and voter turnout. Overseas Vote Foundation Research Newsletter. 2010 Aug 2;4:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkbride JB. Migration and psychosis: our smoking lung? World Psychiatry. 2017 Jun 1;16(2):119–20. doi: 10.1002/wps.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H, Cohen P, Chen S. How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Communications in Statistics—Simulation and Computation®. 2010 Mar 31;39(4):860–4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnett JH, Smoller JW. The genetics of bipolar disorder. Neuroscience. 2009 Nov 24;164(1):331–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, Sham P, Katz R, Cardno A. The Heritability of Bipolar Affective Disorder and the Genetic Relationship to Unipolar Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(5):497–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandez-Pujals AM, Adams MJ, Thomson P, McKechanie AG, Blackwood DH, Smith BH, Dominiczak AF, Morris AD, Matthews K, Campbell A, Linksted P. Epidemiology and heritability of major depressive disorder, stratified by age of onset, sex, and illness course in Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study (GS: SFHS) PLoS One. 2015 Nov 16;10(11):e0142197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hettema JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS. A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001 Oct 1;158(10):1568–78. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Altweck L, Marshall TC, Ferenczi N, Lefringhausen K. Mental health literacy: a cross-cultural approach to knowledge and beliefs about depression, schizophrenia and generalized anxiety disorder. Frontiers in psychology. 2015:6. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran TV. Developing cross-cultural measurement. Pocket Guides to Social Work R. 2009 Mar 27; [Google Scholar]

- 37.Acosta-Belén E, Santiago CE. Puerto Ricans in the United States: A contemporary portrait. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2006. May 15, [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salas-Wright CP, Clark TT, Vaughn MG, Córdova D. Profiles of acculturation among Hispanics in the United States: links with discrimination and substance use. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2015 Jan;50(1):39. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0889-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maynard BR, Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn S. Bullying victimization among school-aged immigrant youth in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016 Mar 31;58(3):337–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz SJ, Unger J, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health. Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America: a portrait. Univ of California Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alba R, Foner N. Comparing immigrant integration in North America and Western Europe: How much do the grand narratives tell us? International Migration Review. 2014 Sep;1(s1):48. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salas-Wright CP, Robles EH, Vaughn MG, Córdova D, Pérez-Figueroa RE. Toward a typology of acculturative stress: results among Hispanic immigrants in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2015 May;37(2):223–42. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Insel TR. Assessing the economic costs of serious mental illness. The American journal of psychiatry. 2008 Jun;165(6):663. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Capps R, Fix ME, Passel JS, Ost J, Perez-Lopez D. A profile of the low-wage immigrant workforce. The urban institute; 2003. Retrieved from: http://webarchive.urban.org/publications/310880.html. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopez G, Bialik K. Key findings about U.S. immigrants. Pew Research Center; 2017. Retrieved from: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/05/03/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/ [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams RH, Jr, Page J. Do international migration and remittances reduce poverty in developing countries? World development. 2005 Oct 1;33(10):1645–69. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van de Mortel TF. Faking it: social desirability response bias in self-report research. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, The. 2008 Jun;25(4):40. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zong J, Batalova J, Hallock J. Frequently requested statistics on immigrants and immigration in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 2018 Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states#Refugees.

- 50.Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG. A “refugee paradox” for substance use disorders? Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2014 Sep 1;142:345–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG. A “refugee paradox” for substance use disorders? Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2014 Sep 1;142:345–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]