Abstract

Objective:

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been associated with the development of diabetes mellitus which is characterized by disorders of collagen production and impaired wound healing. This study analyzed the effects of photobiomodulation (PBM) mediated by laser and light-emitting diode (LED) on the production and organization of collagen fibers in an excisional wound in an animal model of diabetes, and the correlation with inflammation and mitochondrial dynamics.

Methods:

Twenty Wistar rats were randomized into 4 groups of 5 animals. Groups: (SHAM) a control non-diabetic wounded group with no treatment; (DC) a diabetic wounded group with no treatment; (DLASER) a diabetic wounded group irradiated by 904 nm pulsed laser (40 mW, 9500 Hz, 1 min, 2.4 J); (DLED) a diabetic wounded group irradiated by continuous wave LED 850 nm (48 mW, 22 s, 1.0 J). Diabetes was induced by injection with streptozotocin (70mgAg). PBM was carried out daily for 5 days followed by sacrifice and tissue removal.

Results:

Collagen fibers in diabetic wounded skin were increased by DLASER but not by DLED. Both groups showed increased blood vessels by atomic force microscopy. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was higher and cyclooxygenase (COX2) was lower in the DLED group. Mitochondrial fusion was higher and mitochondrial fusion was lower in DLED compared to DLASER.

Conclusion:

Differences observed between DLASER and DLED may be due to the pulsed laser and CW LED, and to the higher dose of laser. Regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis may be an important mechanism for PBM effects in diabetes.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Photobiomodulation therapy, Laser versus LED, Diabetic wound healing, Mitochondrial fission and fusion, Collagen fibers, Atomic force microscopy

1. Introduction

Photobiomodulation (PBM) is used to improve wound healing [1], promote pain relief [2], and improve muscle performance [3]. One of the basic mechanisms is to stimulate mitochondrial function when the red or near-infrared light is absorbed by cytochrome c oxidase [4].

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic disease characterized by high glycemia due to insufficient production or utilization of insulin [5]. DM reduces collagen synthesis [6–8] caused by an inflammatory state associated with oxidative stress [9]. DM can lead to dysregulation of the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Lower VEGF levels in diabetic wounds impair angiogenesis in cutaneous wound healing [10]. On the other hand, up-regulated COX-2 expression (11) is associated with increased expression of VEGF (particularly in the eyes leading to diabetic retinopathy) [12–14].

Mitochondrial homeostasis depends on the balance between fusion and fission processes. Mitochondrial fusion helps reduce mitochondrial stress by mixing the contents of partially damaged mitochondria [15]. Fission allows the creation of new mitochondria, but it also enables the removal of damaged mitochondria. Mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS1) is a component of a mitochondrial complex called the “ARCo- some” that promotes mitochondrial fission [16]. Fusion between mitochondrial outer membranes is mediated by membrane-anchored dy- namin family members called “mitofusins” MFN1 and MFN2. Fusion is diminished in the muscles of obese and diabetic individuals and is associated with insulin resistance after bariatric surgery [17]. Disorders of mitochondrial function may lead to overproduction of ROS [17] and have been implicated in the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [18, 19].

This goal of this study was to investigate collagen production in the wounded skin of diabetic rats treated with PBM mediated either by a pulsed laser (904 nm) or a continuous wave LED (805 nm). Atomic force microscopy, and COX-2, VEGF, FIS1 and MFN2 immuno-expres- sion were measured to understand the mitochondrial mechanisms.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

The Federal University of Sao Carlos ethics committee approved this research under protocol no. 01/2013. In this study, 20 male Wistar rats were used (45 days of age and weight 200–250 g), housed in controlled temperature and humidity with 12 h light-dark cycle, with water ad libitum and a commercial diet. Rats were randomized into groups (n = 5 each): (SHAM) a control non-diabetic wounded group with no treatment; (DC) a diabetic wounded group with no treatment; (DLASER) a diabetic wounded group irradiated by 904 nm pulsed laser; (DLED) a diabetic group with an incision irradiated by continuous wave LED 850 nm.

2.2. DM Induction

The animals of SHAM group received an intraperitoneal injection with 0.022 mL NaCl 0.9% solution. Animals of diabetic groups (DC, DLASER and DLED) received an injection with streptozotocin (70 mg/ kg in citrate buffer, pH = 4.5). For induction of diabetes we used a previously described methodology [20, 21]. Rats were prepared fasting for 6 h before anesthetized by thiopental (40 mg/kg/2.5% IP) and after this, received an intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin in a prone position (solution 70 mg/kg - STZ) associated to citrate buffer solution (pH 4.5). Glucose levels were measured with a glucometer in blood samples taken from the tail vein (AccuChek, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Although in 10 days to 14 days is sufficient to obtain a hyperglycemic condition, treatments starts 90 days after diabetes induction by STZ to guarantee a chronic diabetic state to simulate clinical conditions. Reason for this it is because diabetic foot and another skin diseases in diabetes are more common in elderly people, our main motivation for this research and the results of this research can provide evidence for future translational research.

2.3. Surgical Procedures

On the 90th-day post DM induction, blood was collected from tail vein and animals with glycemic levels of 300mg/dL or above were included in the study [22]. Anesthesia was performed intraperitoneally (dose of thiopental 40 mL/kg IP Cristália®, Itapira, Brazil). The skin on the dorsal region was disinfected with povidone-iodine and was cut with a surgical scalpel until the depth reached the hypodermis. An incision was made 2 cm wide and 2 cm long, on the posterior iliac crest of the animal and the skin was removed [23]. The animals were housed in pairs.

2.4. Treatment

The animals were randomized by lottery using opaque envelopes. The group denominated DLASER received laser treatment and animals denominated DLED received LEDT treatment. The diode laser 904 nm GaAs Laserpulse model (IBRAMED, Amparo, Brazil), and a LED proto type was delivered on the wound edges.

The first application of PBM was delivered immediately after wounding, and PBM was repeated once a day for the next five days. Immediately after the last application of PBM the rats were anesthetized and the entire area of the wound was removed for histological analysis. The rats were then sacrificed by carbon dioxide euthanasia. Table 1 shows the parameters of the laser and LED devices.

Table 1.

Photobiomodulation parameters.

| Parameters | Laser | LED |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength | 904 nm | 850 nm |

| Average radiant power | 40 mW | 48 mW |

| Pulse structure | Duty cycle 20%; Pulse duration 60 nsec; Frequency 9500 Hz | Continuous wave |

| Fluence | 18.33 J/cm2 | 14.69 J/cm2 |

| Time | 1 min | 22 s |

| Energy | 2.4 J | 1.0J |

| Beam spot size at target | 0.1309 cm2 | 0.196 cm2 |

| Technique | Contact | Contact |

| Number of points irradiated | 1 | 1 |

| Frequency of treatment | 1 × /day for 5 days | 1 × /day for 5 days |

2.5. Sample Collection and Processing

The removed skin of the rats was fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 24 h. and embedded in paraffin blocks. The paraffin blocks were sectioned in series of 3 cuts (5 μm) each transversely (Microtome Leica Microsystems SP 1600, Nussloch, Germany) and attached to glass slides.

2.6. Collagen Analysis

For collagen analysis, the glass slides were stained with picrosirius red and cross-sectioned for analysis by fluorescence microscopy using a 20 × objective and a software capture system AxioVision 4.7.2.0 v (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The images were processed using ImageJ 1:49 software, 64-bit version (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA), using plugin color deconvolution. The images were analyzed for the relative percentage of collagen in the total tissue [24, 25].

2.7. Atomic Force Microscopy

For atomic force microscopy, the slides were observed using a Flex- Axiom Nanosurf device (Nanosurf, Liestal, Switzerland). The tissue was rehydrated, and no histological staining was used. The samples were scanned in vibrational mode using NanoWorld tip model NCSTR with a typical resonance frequency of 160KHz.

2.8. Immunohistochemistry

Xylene and rehydration in graded ethanol were used to remove paraffin from the blocks. Samples were preincubated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 10 min and blocked with goat serum in PBS (20 min). The following primary rabbit antibodies and dilutions were used for a 2h incubation. Polyclonal anti-cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA), anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA), anti-mitofusin 2 (MFN2, 1:900, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA) and anti-mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS1, 1:800, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA). A biotin-conjugated secondary antibody anti-rabbit IgG (1: 200, (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in PBS for 30 min) was incubated, and then a peroxidase-conjugated avidin-biotin complex was applied for 30 min. Finally, a solution of 3–3´-diaminobenzidine (0.05%) and Harris hematoxylin. The expression levels of COX-2, VEGF, MFN2 and FIS1 were assessed semi-qualitatively (presence and location of the staining) using an optical light microscope. For quantification of positive cells per field, we used IHC Profiler plugin compatible with soft-ware ImageJ [26] and was scored using a scale from 1 to 4 [23] (1 = negative, 2 = low positive, 3 = positive, and 4 = highly positive). [25, 27, 28].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Histopathological, immunohistochemistry and collagen analyses were performed under double-blind conditions and data were tested by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) repeat measures, followed by Tukey’s test. The significance level was 5% (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Collagen Analysis

The data on the % of collagen in the skin samples are listed in Table 2. The lowest values of collagen were found in the DC group consistent with the inhibitory effects of diabetes on wound healing. There was a statistical difference between the SHAM group and DLASER (p = 0.01) and between DLASER and DLED (p = 0.009). The DLED group did not show any increased collagen content which remained at the same level as the DC group.

Table 2.

Relative percent collagen in total.

| Groups | Relative percent collagen in total tissue |

|---|---|

| SHAMa | 6.08 ± 0.80b,c,d* |

| DCb | 3.01 ± 0.10 |

| DLASERc | 11.38 ± 0.1b,d* |

| DLEDd | 3.56 ± 0.5 |

Table. 2 Statistical analysis using morphometric computational systems to determine amount collagen by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Groups: non-diabetic control (SHAM), diabetic non treated (DC), diabetic treated with LLLT (DLASER) and diabetic LEDT treatment (DLED).

The significance level was set at

p < 0.05.

Versus Sham group.

Versus DC group.

Versus DLASER group. Date are showed mean ± SEM. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Versus DLED group.

3.2. Atomic Force Microscopy

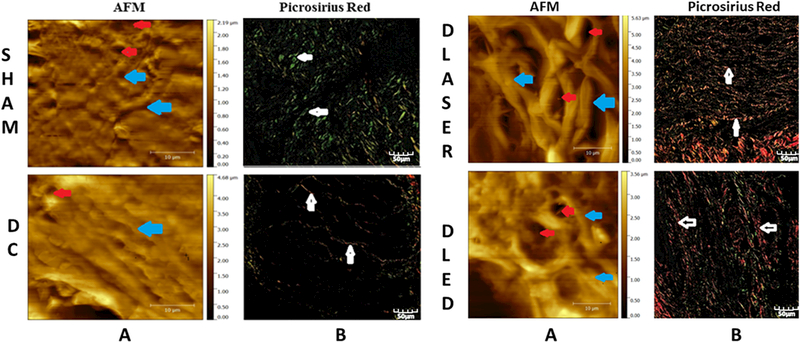

AFM has advantages including rapid specimen preparation and can provide information on the mechanical features of the tissue. Picrosirius red staining and fluorescence microscopy was used to identify collagen fibers on the glass slides. In the SHAM group, AFM showed a limited number of fibers, but the network of interwoven fibers, characteristic of the extracellular matrix had not yet been well-formed. In the diabetic control group (DC) only a few fibers were observed in AFM. The DLASER group showed a moderate deposition of mature collagen fibers in the matrix. In the DLED group AFM showed a well-organized deposition of collagen fibers (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Atomic force microscope (AFM) and picrosirius red fluorescence microscopy images of skin of diabetic and non-diabetic rats: SHAM, DC. DLASER and DLED. A) Sections analyzed by AFM; blue arrows indicate fibers that make up the ECM; red arrows show the formation of new blood vessels. B) Fluorescence staining with picrosirius red; white arrows indicate collagen fibers.

3.3. Immunohistochemistry

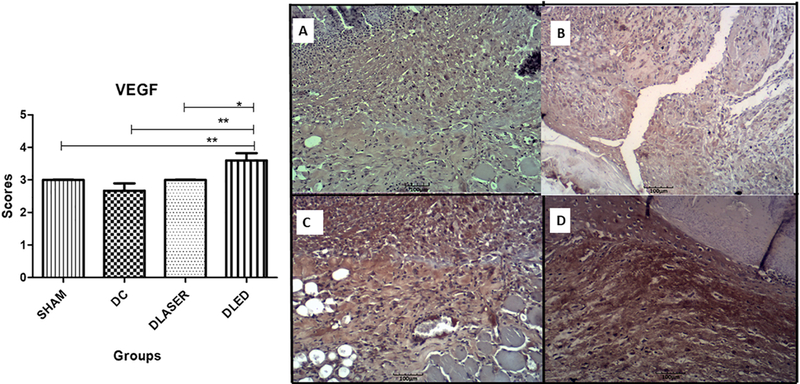

3.3.1. VEGF

The DLED group demonstrated a statistically higher expression of VEGF compared to DC (p = 0.000), to DLASER (p = 0.02) and to SHAM (p = 0,002) after 5 days treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean scores for immunostaining of VEGF. A single asterisk represents differences of p < 0.05 and two asterisks represents p = 0.002. A) SHAM - control non-diabetic wounded group with no treatment; B) DC - diabetic wounded group with no treatment; C) DLASER- diabetic wounded group irradiated by 904 nm pulsed laser (40 mW, 9500 Hz, 1 min, 2.4 J); D) DLED - diabetic wounded group irradiated by continuous wave LED 850 nm (48 mW, 22 s, 1.0 J).

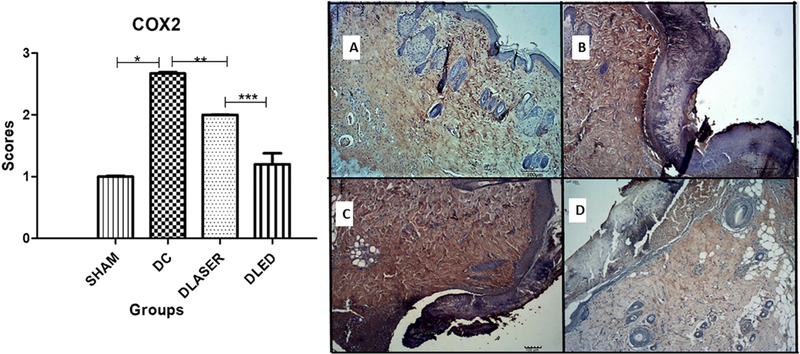

3.3.2. COX-2

DLED group showed a significantly lower expression of COX2 compared to DC (p = 0.008) and to DLASER (p = 0.005). In addition, SHAM group demonstrated significantly lower COX2 than DC (p = 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mean scores for immunostaining of COX-2. A single asterisk represents differences of p = 0.001, two asterisks represents p = 0.008 and three asterisks represents p = 0.005. A) SHAM - control non-diabetic wounded group with no treatment; B) DC - diabetic wounded group with no treatment; C) DLASER- diabetic wounded group irradiated by 904 nm pulsed laser (40 mW, 9500 Hz, 1 min, 2.4 J); D) DLED - diabetic wounded group irradiated by continuous wave LED 850 nm (48mW, 22 s, 1.0 J).

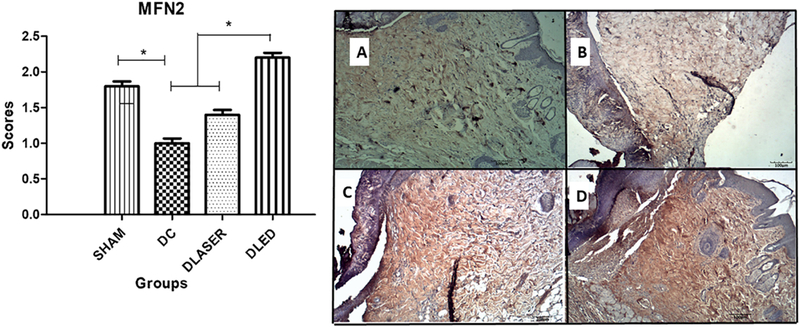

3.3.3. MFN2

DC group had the lowest expression with significant differences compared to DLED groups (p = 0.000), SHAM (p = 0.001). In addition, a significant difference between the DLASER and DLED groups (p = 0.001) was observed. (Fig. 4):

Fig. 4.

Mean scores for immunostaining of MFN2. A single asterisk represents differences of p = 0.00 and p = 0.04 by two asterisks. A) SHAM - control non-diabetic wounded group with no treatment; B) DC - diabetic wounded group with no treatment; C) DLASER- diabetic wounded group irradiated by 904 nm pulsed laser (40 mW, 9500 Hz, 1 min, 2.4 J); D) DLED - diabetic wounded group irradiated by continuous wave LED 850 nm (48 mW, 22 s, 1.0 J).

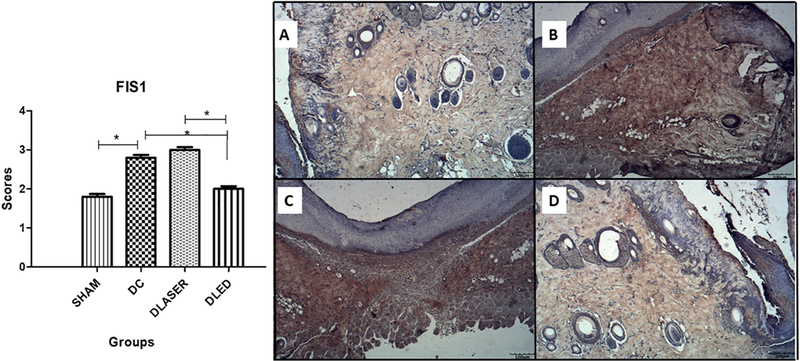

3.3.4. FIS1

DLED group demonstrated statistically lower expression compared to DLASER (p = 0.000) and DC (p = 0.001). Also, DLASER showed statistically higher expression compared to SHAM (p = 0.000) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Mean an SD scores for immunostaining of FIS1. A single asterisk represents differences of p = 0.04. Bars represent SD. A) SHAM - control non-diabetic wounded group with no treatment; B) DC - diabetic wounded group with no treatment; C) DLASER- diabetic wounded group irradiated by 904 nm pulsed laser (40 mW, 9500 Hz, 1 min, 2.4 J); D) DLED - diabetic wounded group irradiated by continuous wave LED 850 nm (48 mW, 22 s, 1.0 J).

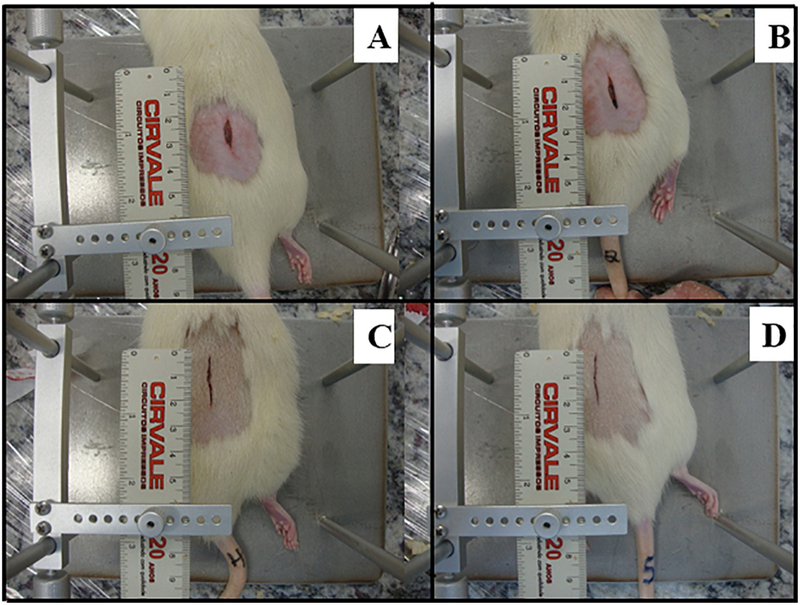

3.4. Wound Healing

Wound Healing is demonstred in fig. 6, which shows comparative picture between groups SHAM, DC, DLASER and DLED. SHAM group was observed that animals or totally closed the wounds or partially but not had any infections or edema (0.33 ± 0.2). DC group presented two infections situations and not had completely closed wounds (1.03 ± 0.3). DLASER and DLED groups not had infections and all closed in the final of experiment.

Fig. 6.

Comparative wounds closure photographs between the laser and LED treatments. A) SHAM - control non-diabetic wounded group with no treatment; B) DC - diabetic wounded group with no treatment; C) DLASER- diabetic wounded group irradiated by 904 nm pulsed laser (40 mW, 9500 Hz, 1 min, 2.4 J); D) DLED - diabetic wounded group irradiated by continuous wave LED 850 nm (48 mW, 22 s, 1.0 J).

4. Discussion

This study showed that the collagen fiber content in wounded diabetic skin was reduced in comparison with control wounded skin. Treatment with PBM mediated by laser (DLASER) increased the collagen content compared to SHAM and dramatically increased the collagen compared to DC. However PBM mediated by LED (DLED) did not show the same effect. It is not at present entirely clear why the laser had a beneficial effect on collagen and the LED did not, considering that the LEDT did have a beneficial effect on VEGF and blood vessel formation and on mitochondrial dynamics.

AFM showed better organization of collagen fibers and formation of new blood vessels in both PBM groups, when compared with controls. Immunohistochemistry analysis demonstrated increased VEGF in both irradiated groups. However, DLED did show a more pronounced reduction of COX2 expression than DLASER. DLED demonstrated higher MFN2 expression and lower FIS1 expression compared to DLASER. These results suggest that there were differences between the mechanisms of PBM mediated by laser and LED on diabetic wounds, but that broadly speaking, both light sources could be said to be beneficial. The LED appeared to be better at exerting anti-inflammatory effects compared to the laser, and this may have been related to the somewhat lower dose employed (1 J) compared to the laser (2.4 J). It is possible that the higher dose of laser stimulated collagen formation better than the lower dose of LED.

In DM, inflammatory mediators are dysregulated [29] with a more prolonged inflammatory response that is proposed to inhibit wound healing. Our findings agree with a report from Peplow et al. [30]. These authors found that animals irradiated with LLLT 1.6 J showed collagen that occupied the whole edge of the wound,and reduced inflammatory exudate. They provided evidence that DM reduced vascular density, interfered with VEGF signaling and reduced tissue perfusion, demonstrating an impaired angiogenic response [31]. Our findings indicated that the expression of VEGF increased most with DLED when compared to SHAM, DC and DLASER. These results reinforce other studies which diabetic rats showed impaired VEGF signaling leading to lower proliferation and migration of endothelial cells [32]. Expression of COX-2 in DLED group was lower compared to DLASER. Since COX-2 can regulate the expression of VEGF [11–13] thus might explain why the levels of VEGF were also highest with LEDT. COX-2 has been intensely studied for many years as an inflammatory mediator, and up- regulation of COX-2 expression has been associated with the up-reg- ulation of VEGF and has been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy [12, 13].

Increase oxidative stress in diabetes, leads to excessive mitochondrial fission, causing mitochondrial damage and eventual cellular damage and cell death [17]. In mammals, mitochondrial fusion is controlled by MFN1 and MFN2 on the mitochondrial outer membrane and the inner membrane. Bach et al. [33] and Hernandez-Alvarez [34] found reduced expression of MFN2 in obese skeletal muscle and in type 2 DM. It is proposed that deficiency of MFN2 causes mitochondrial dysfunction, increases the production of H2O2 and oxidative stress, eventually producing insulin resistance in the liver and skeletal muscle [33, 34]. Fission is carried out by the cytoplasmic protein dynamin- related protein 1 (Drpl) that moves to the outer mitochondrial membrane and participates in the mitochondrial fragmentation reaction. Furthermore, FIS1 protein is proposed to function as an adapter for Drpl [35]. Our findings showed increased MFN2 scores in wounded diabetic animals irradiated with laser and LED and which leads us to propose that one possible mechanism of action of PBM on the wound healing process is regulation of the homeostatic balance between mitochondrial fusion and fission.

LED showed the best results to minimize inflammation and stimulate the formation of new vessels. Laser demonstrated the best action to stimulate the formation of new collagen fibers. There were additional differences between LLLT and LED effects on the factors involved in mitochondrial function (FIS1 and MFN2). It is always difficult to design experiments that directly compare laser with LED. Here the differences were the fact that the laser was superpulsed while the LED was CW. Moreover the dose of laser was higher than LED (2.4 J vs 1 J). Further work is necessary to test whether there is any intrinsic difference between laser and LED when all the parameters are absolutely identical.

We believe that this study can provide information to inform new research to understand whether there is indeed a difference between action mechanisms between laser and LED and to understand the effects of PBM on regulating mitochondrial homeostasis while stimulating mitochondrial metabolism.

5. Conclusions

We demonstrated that collagen production in wounded diabetic animals was upregulated by laser PBM. The possible mechanism of action of PBM was modulation of inflammation and the homoeostasis between mitochondrial fusion and fission. We cannot exclude other mechanisms because there are many complex signaling pathways involved in PBM and diabetic wound healing. However, our observations provide data for future research on the therapeutic implications of laser and LED on diabetic wound healing

Acknowledgements

Authors received grants from Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - FUNCAP (proc.0778929/ 2015) (grant number 99999.006648/2015–00) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior - Capes. MRH was supported by US NIH grants R01AI050875 and R21AI121700.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- [1].Hunter S, Langemo D, Hanson D, Anderson J, Thompson P, The use of mono-chromatic infrared energy in wound management, Adv. Skin Wound Care 20 (2007) 265–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lizarelli RFZ, Miguel FAC, Freitas-Pontes KM, Villa GEP, Nunez SC, Bagnato VS, Dentin hypersensitivity clinical study comparing LILT and LEDT keeping the same irradiation parameters, Laser Phys. Lett. 7 (11) (2010) 805–811. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ferraresi C, Beltrame T, Fabrizzi F, Pereira do Nascimento ES, Karsten M, Francisco CdO, et al. Muscular pre-conditioning using light-emitting diode therapy (LEDT) for high-intensity exercise: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial with a single elite runner, Physiother. Theory Prac. 31 (5) (2015) 354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Karu T, Mitochondrial signaling in mammalian cells activated by red and near-IR radiation, Photochem. Photobiol. 84 (5) (2008) 1091–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Alberti K, Zimmet PZ, W.H.O. Consultation, Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus - Provisional report of a WHO consultation, Diabet. Med. 15 (7) (1998) 539–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Meireles GCS, Santos JN, Chagas PO, Moura AP, Pinheiro ALB, Effectiveness of laser photobiomodulation at 660 or 780 nm on the repair of third-degree burns in diabetic rats, Photomed. Laser Surg. 26 (1) (2008) 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cruz J, Oliveira MA, Hohman TC, Fortes ZB, Influence of tolrestat on the defective leukocyte-endothelial interaction in experimental diabetes, Eur. J. Pharmacol. 391 (1–2) (2000) 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Black E, Vibe-Petersen J, Jorgensen LN, Madsen SM, Agren MS, Holstein PE, et al. , Decrease of collagen deposition in wound repair in type I diabetes independent of glycemic control, Arch. Surg. 138 (1) (2003) 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Falanga V, Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot, Lancet 366 (9498) (2005) 1736–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wang B, Liu D, Wang C, Wang Q, Zhang H, Liu G, et al. , Tentacle extract from the jellyfish Cyanea capillata increases proliferation and migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells through the ERK1/2 signaling pathway, PLoS ONE 12 (12) (2017) e0189920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li T, Hu J, Du S, Chen Y, Wang S, Wu Q, ERKl/2/COX-2/PGE(2) signaling pathway mediates GPR91-dependent VEGF release in streptozotocin-induced diabetes, Mol. Vis. 20 (2014) 1109–1121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nagoya H, Futagami S, Shimpuku M, Tatsuguchi A, Wakabayashi T, Yamawaki H, et al. , Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-1 is associated with angiogenesis and VEGF production via upregulation of COX-2 expression in esophageal cancer tissues, Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 306 (3) (2014) (G183–G90). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhou L-H, Hu Q, Sui H, Ci S-J, Wang Y, Liu X, et al. , Tanshinone II-A inhibits angiogenesis through down regulation of COX-2 in human colorectal cancer, Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 13 (9) (2012) 4453–4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shiraya T, Kato S, Araki F, Ueta T, Miyaji T, Yamaguchi T, Aqueous cytokine levels are associated with reduced macular thickness after intravitreal ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema, PLoS ONE 12 (3) (2017) e0174340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Korobova F, Ramabhadran V, Higgs HN, An actin-dependent step in mitochondrial fission mediated by the ER-associated formin INF2, Science 339 (6118) (2013) 464–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Otera H, Mihara K, Discovery of the membrane receptor for mitochondrial fission GTPase Drpl, Small GTPases 2 (3) (2011) 167–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vincent AM, Edwards JL, McLean LL, Hong Y, Cerri F, Lopez I, et al. , Mitochondrial biogenesis and fission in axons in cell culture and animal models of diabetic neuropathy, Acta Neuropathol. 120 (4) (2010) 477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ohkuwa T, Sato Y, Naoi M, Hydroxil radical formation in diabetic rats induced by streptozotocin, Life Sci. 56 (21) (1995) 1789–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Winiarska K, Drozak J, Wegrzynowicz M, Fraczyk T, Bryla J, Diabetes-induced changes in glucose synthesis, intracellular glutathione status and hydroxyl free radical generation in rabbit kidney-cortex tubules, Mol. Cell. Biochem. 261 (1–2) (2004) 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Farias VX, Macedo FH, Oquendo MB, Tome AR, Bao SN, Cintra DO, et al. , Chronic treatment with D-chiro-inositol prevents autonomic and somatic neuropathy in STZ-induced diabetic mice, Diabetes Obes. Metab. 13 (3) (2011) 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tatmatsu-Rocha JC, Ferraresi C, Hamblin MR, Damasceno Maia F, do Nascimento NRF, Driusso P, et al. , Low-level laser therapy (904 nm) can increase collagen and reduce oxidative and nitrosative stress in diabetic wounded mouse skin, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 164 (2016) 96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schindl A, Schindl M, Pernerstorfer-Schon H, Kerschan K, Knobler R, Schindl L, Diabetic neuropathic foot ulcer: successful treatment by low-intensity laser therapy, Dermatology 198 (3) (1999) 314–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Manzi FR, Bóscolo FN, SMd Almeida, FM Tuji. Morphological study of the radioprotective effect of vitamin E (dl-alpha-tocopheril) in tissue reparation in rats.Estudo morfologico do efeito radioprotetor da vitamina E (dl-alfa-tocoferil) na reparção tecidual em ratos, Radiol. Bras. 36 (6) (2003) 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ruifrok AC, Katz RL, Johnston DA, Comparison of quantification of histo- chemical staining by hue-saturation-intensity (HSI) transformation and color- de- convolution, Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 11 (1) (2003) 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Underwood RA, Gibran NS, Muffley LA, Usui ML, Olerud JE, Color sub- tractive- computer- assisted image analysis for quantification of cutaneous nerves in a diabetic mouse model, J. Histochem. Cytochem. 49 (10) (2001) 1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Varghese F, Bukhari AB, Malhotra R, De A, IHC profiler: an open source plugin for the quantitative evaluation and automated scoring of immunohistochemistry images of human tissue samples, PLoS ONE 9 (5) (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ruifrok AC, Katz RL, Johnston DA, Comparison of quantification of histo- chemical staining by hue-saturation-intensity (HSI) transformation and color- de- convolution. Applied immunohistochemistry & molecular morphology, AIMM 11 (1) (2003) 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Di Cataldo S, Ficarra E, Acquaviva A, Macii E, Automated segmentation of tissue images for computerized IHC analysis, Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 100 (1) (2010) 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chen J, Kasper M, Heck T, Nakagawa K, Humpert PM, Bai L, et al. , Tissue factor as a link between wounding and tissue repair, Diabetes 54 (7) (2005) 2143–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chung T-Y, Peplow PV, Baxter GD, Laser photobiomodulation of wound healing in diabetic and non-diabetic mice: effects in splinted and unsplinted wounds, Photomed. Laser Surg. 28 (2) (2010) 251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Boodhwani M, Sellke FW, Therapeutic angiogenesis in diabetes and hypercholesterolemia: influence of oxidative stress, Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11 (8) (2009) 1945–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hu J, Wu Q, Li T, Chen Y, Wang S, Inhibition of high glucose-induced VEGF release in retinal ganglion cells by RNA interference targeting G protein-coupled receptor 91, Exp. Eye Res. 109 (2013) 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bach D, Naon D, Pich S, Soriano FX, Vega N, Rieusset J, et al. , Expression of Mfn2, the Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A gene, in human skeletal muscle, Diabetes 54 (9) (2005) 2685–2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Isabel Hernandez-Alvarez M, Thabit H, Burns N, Shah S, Brema I, Hatunic M, et al. , Subjects with early-onset type 2 diabetes show defective activation of the skeletal muscle PGC-1 alpha/mitofusin-2 regulatory pathway in response to physical activity, Diabetes Care 33 (3) (2010) 645–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mechanism study on mitochondrial fragmentation under oxidative stress caused by high-fluence low-power laser irradiation, in: Wu S, Zhou F, Xing D (Eds.), International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2012. [Google Scholar]