Abstract

Background

Three methods of leukoreduction (LR) are used world-wide: filtration, buffy-coat removal, and a combination of the previous two methods. Additionally, there are number of additive solutions (AS) used to preserve RBC function throughout storage. During RBC storage, pro-inflammatory activity accumulates; thus, we hypothesize that both the method of LR and the additive solution affect the accumulation of pro-inflammatory activity.

Methods

Ten units of whole blood were drawn from healthy donors, the RBC units were isolated, divided in half by weight, and leukoreduced by: 1) buffy coat removal, 2) filtration, or 3) buffy coat removal and filtration (combination-LR), stored in bags containing AS-3 per AABB criteria, sampled weekly, and the supernatants isolated and frozen (−80°C). RBC units drawn from healthy donors into AS-1, AS-3, or AS-5 containing bags were also stored, sampled weekly, and the supernatants isolated and frozen. The supernatants were assayed for PMN priming activity and underwent proteomic analyses.

Results

Filtration and combination LR decreased priming activity accumulation vs. buffy coat LR, although the accumulation of priming activity was not different during storage. Combination LR increased hemolysis vs. filtration via proteomic analysis. Priming activity from AS-3 units was significant later in storage versus AS-1 or AS-5 stored units.

Conclusions

Although both filtration and combination LR decrease the accumulation of pro-inflammatory activity vs. buffy coat LR, combination LR is not more advantageous over filtration, has increased costs, and may cause increased hemolysis. In addition, AS-3 decreases the early accumulation of PMN priming activity during storage versus AS-1 or AS-5.

Keywords: transfusion, biologic response modifiers, red blood cell, leukoreduction, neutrophil priming, storage

Introduction

Pre-storage leukoreduction (LR) of whole blood (WB) or red blood cells (RBC) reduces white blood cell (WBC) and platelet contamination and decreases febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reactions, alloimmunization, and the accumulation of biologic response modifiers (BRMs), including: soluble CD40 ligand, cytokines, chemokines, and lysophosphatidylcholines (lyso-PCs) some of which have been implicated in the development of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI).1–6 Three primary methods of LR are used worldwide: Buffy coat removal (BCR), in-line filtration, and the combination approach using both of the previous methods in sequence.7–11 BCR separates cells based on their differences in specific gravity and is the predominant method of LR used in developing countries due to the lower cost. In-line filtration uses charged-based adhesion of negatively charged leukocytes in order to remove WBCs from blood products and is used predominately in the United States.7,8,10,11 The combination approach employs buffy coat removal followed by filtration prior to storage of the red blood cell units and is predominately employed in Canada and Western Europe.10

Additive solutions allow for the storage of RBCs for 6 weeks and have specific uses with different filtration strategies and come as a part of the leukoreduction sets from specific manufacturers.7,12 Metabolomic analyses of RBCs stored in AS-3 have demonstrated that AS-3 appears to maintain RBCs in a state of relative homeostasis until D14, when the RBC metabolism changes significantly.13–16

Priming agents accumulate during the routine storage of cellular blood components and may serve as the second event in the 2-step model of TRALI. In addition, testing for the accumulation of neutrophil priming activity during exposure to BRMs correlates to the pathophysiological development of TRALI.17 There have not yet been side-by-side comparisons of these LR methods in terms of their ability to minimize the neutrophil (PMN) priming activity in the supernatant. We hypothesize that LR by buffy coat is inferior to LR by filtration and that there is no significant difference between filtration and the combination method in terms of minimizing the accumulation of PMN priming activity, during routine storage.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Corporation (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise specified. All solutions and buffers were made from sterile water for human injection (United States Pharmacopeia (USP)) purchased from Baxter Healthcare (Deerfield, NY), followed by sterile filtering with Nalgene MF75 disposable sterilization filter units from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). ELISA kits for α-enolase (ENO1) and arachidonic acid were purchased from either Abnova (Walnut, CA) or US Biological (Swampscott, MA). Antibodies for peroxiredoxin-6 were purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA).

Blood Sampling and Processing

Five units of whole blood were drawn from healthy volunteer donors after obtaining informed consent under a protocol approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB) at the University of Colorado Denver (Aurora, CO). Plasma was removed by centrifugation, 5,000g for 7 min, and expression using a Compomat (Fresenius Kabi, Lake Zurich, IL). The RBCs were suspended in AS-3 and then equally divided by weight; thus, the buffy coats were present in the RBCs (please see the Results section). Of the remaining RBCs + buffy coat 50% were LR by buffy coat removal by expression into an in-line bag. and 50% were LR by in-line filtration (Haemonetics BPF4) and both were stored at 1–6° C per AABB criteria on day 1, 24 hours after whole blood collection.7 Thus, separation of the plasma and buffy coat was completed by a top/top expression procedure. Sterile couplers were used to obtain samples weekly during the 42 days of storage. The supernatant was isolated by centrifugation (5,000g for 7 min, followed by 12,500g for 6 min) and stored at −80° C. The same protocol was repeated with another 5 units of RBCs stored in AS-3, with 50% undergoing in-line filtration and the other 50% undergoing initial buffy coat removal followed by in-line filtration.

Lipid Extractions

Lipids were isolated from the plasma samples using a 1:1:1 chloroform:methanol:water:0.2% acetic acid extraction, as previously published.18 Lipids were then solubilized with 1.25% fatty acid free human serum albumin and used to assess in PMN priming activity, as previously reported.19,20

Neutrophil isolation and priming

Neutrophils (PMNs) were isolated from heparinized whole blood after informed consent was obtained from healthy volunteer donors under an approved protocol by Colorado Multi-Institution Review Board at the University of Colorado Denver by standard technique using dextran sedimentation, ficoll-paque separation, and hypotonic lysis, as previously described.19 PMNs (3.5 x105 cells) were incubated in Krebs Ringer Phosphate with Dextrose, pH 7.35 (KRPD) buffer along with supernatant or lipid samples (10%) for 5 min at 37°C then activated with 1μM formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLF) and the superoxide dismutase inhibitable maximal rate of superoxide (O2−) was measured at 550 nm, as previously reported, for the supernatants from RBC units.19,21 Priming activity was measured as the augmentation of the maximal rate of superoxide production by PMNs activated with fMLF. Neutrophil priming data was also taken from prior work completed on the supernatants from RBCs on AS1 and AS5, drawn serially during the storage interval as reported.2,19,22,22,23

Proteomics

Immunoreactivity of peroxiredoxin-6, an intracellular RBC enzyme, was completed using Western Blots of the supernatants from the PRBCs. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were also used to quantify α-enolase and arachidonic acid in the plasma supernatants and run according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of proteins in the plasma samples was performed using targeted mass spectroscopy and 13C-labeled QConCAT standards. These assays were completed by the University of Colorado Denver Mass Spectrometry Core proteomics group, as described.24

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± the standard error of the mean. Statistical differences were measured by a paired or an independent ANOVA, with a Bonferonni or a Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis depending upon the equality of variance for these measurements. The independent ANOVA analyses are employed for comparison amongst the RBC units stored in different additive solutions and amongst the BC, filtration, and combination groups. For priming data a p-value <0.05 signified statistical significance and for the QConCat data a p-value <0.01 determined statistical significance.

Results

Separation of the whole blood

To confirm adequate separation of the whole blood complete blood counts were performed on the expressed plasma, and the RBC units following LR. The plasma units demonstrated only modest platelet contamination with platelet counts ranging from 5–20,000/μl data with no leukocytes, similar to previous data.25 In addition buffy coat removal decreased the leukocyte counts by ~1 log (82±6%), the platelet counts by ~1 log (84±9%), and the RBC number by 7.3±0.4%. Filtration decreased the leukocyte counts from an average of 32.2±8.8 to 0±0 (>3.5 logs) and platelet counts from an average of 1,598±662/μl to 0±0 (>2 logs) with a loss in RBC number of 12±1%, which is in agreement with Bonfils Blood Center data, which demonstrated a decrease in weight of RBC units post filtration LR of 10.7±0.2%.

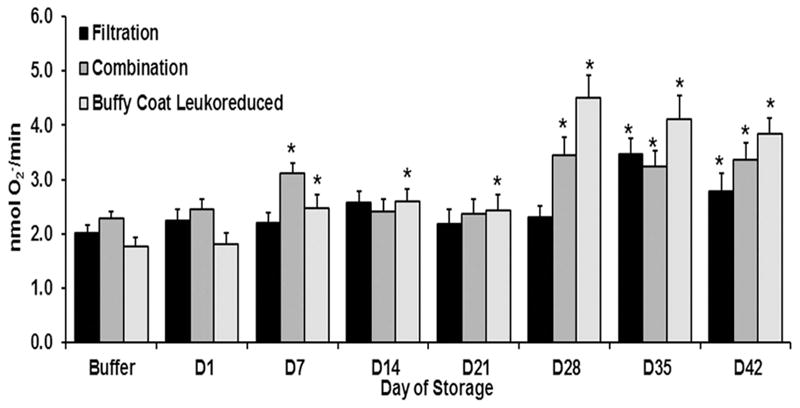

Increased PMN priming activity is present in BCLR supernatants versus filtration or combination LR

The supernatants from all three methods of leukoreduction showed no difference in PMN priming vs. albumin or buffer-treated controls on day (D) 1. Both the BCLR units and the combination LR units contained significantly increased priming activity (p<0.05 vs D1 and buffer-treated controls) on D7 of routine storage, which continued for the BCLR RBC units throughout the storage interval, reaching a relative maximum on D28 that persisted (Fig. 1). In the combination LR RBC units the priming activity reappeared on D28 (p<0.05), reaching a relative maximum, and persisted throughout storage (Fig. 1). In contrast, the supernatant priming activity in the filtered RBC units became significant on D35 (p<0.05) that persisted through D42 of storage (Fig. 1). Moreover, the supernatant from BCLR RBC units contained significantly greater priming activity than filtered RBC units and combination LR RBC units from D28–D42 (p<0.05). On D28 alone, there was 2.0-fold greater PMN priming activity in the supernatants from BCLR RBC units vs. either the combination LR or filtered RBC units (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The supernatants of buffy-coat leukoreduced (BCR) samples accumulated more neutrophil priming activity and the combination LR does not decrease priming activity versus filtration.

The maximal rate of SOD-inhibitable superoxide production is presented as a function of routine RBC storage. Compared to filtration (black bars), BCR (light gray bars) accumulated more PMN priming activity starting on D7 whereas there is no statistical difference versus combination LR (intermediate gray bars) on any of the storage days. * indicates p<0.05 from D1 within treatment and buffer-treated controls.

Combination LR did not decrease PMN priming activity vs. filtration

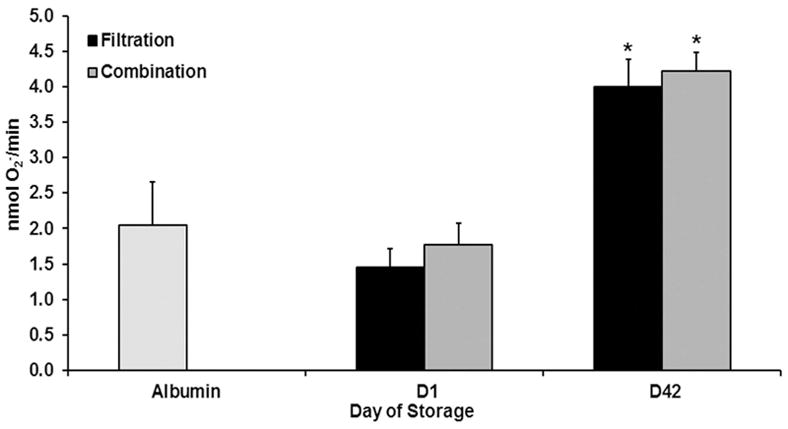

There were no statistical differences in PMN priming activity between D1 supernatants leukoreduced by filtration or combination methods (Fig. 1). To further explore the PMN priming activity, the lipids were extracted from the supernatants of RBC units that underwent combination LR or filtration alone. Lipids were present by D42 which contained increased PMN priming activity in comparison to the lipid extracts from D1 and the albumin treated controls (p<0.05) (Fig. 2). There was no difference in lipid priming activity from the supernatants from D42 of storage for the units that underwent combination LR or filtration alone (Fig. 2).19 In addition, when the arachidonic acid concentration was measured in the supernatants from RBCs leukoreduced by filtration or combination leukoreduction methods there was increased AA concentration on D42 versus D! or D14 of storage, but there were no statistical differences in arachidonic acid concentrations between the two leukoreduction methods (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Lipids extracted from the supernatant of combination LR RBC units do not decrease PMN priming versus the lipids from filtered RBC units.

The maximal rate of SOD-inhibitable superoxide anion production is presented as a function of routine storage. Lipids, known biological response modifiers, which prime PMNs, were isolated from both combination LR and filtration methods and used in PMN priming assays. No difference in priming was found comparing the two methods. * indicates p<0.05 from D1 within treatment and fMLF control and # indicates p <0.05 from filtration LR within day.

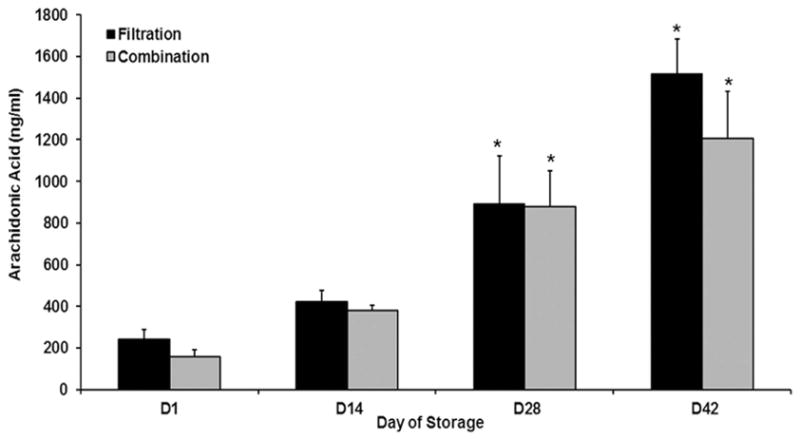

Figure 3. Arachidonic acid similarly accumulates in filtration and combination LR with storage.

Concentrations of arachidonic acid, by ELISA, are presented as a function of routine storage. During storage, in both the filtered and combination LR RBC units there was an increase in arachidonic acid which was increased significantly (p<0.05) on D28 and D42 compared to D1 and D14 of storage. There were no statistical differences in AA concentration detected between the two leukoreduction methods. *= p<0.05 from D1 and D14 within LR groups

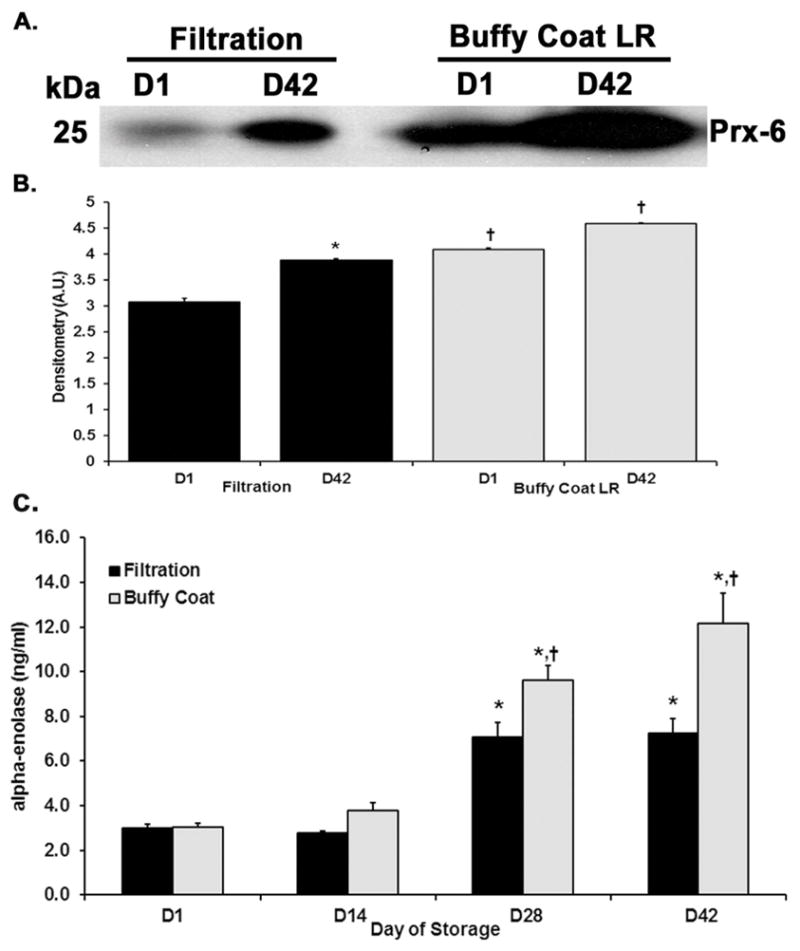

Proteomic analysis of supernatants from RBC units that were leukoreduced by combination of filtrations methods

Peroxiredoxin-6 and α-enolase are two intracellular enzymes which accumulate during red blood cell storage presumably due to RBC lysis or release.26 More immunoreactivity for peroxiredoxin-6 was present in the supernatants from BCLR RBC units vs. units that underwent LR by filtration (Fig. 4). In addition, α-enolase concentrations, via ELISA, showed a similar trend, with greater concentrations in the supernatants from BCLR RBC units in comparison to the supernatants from filtered units. There was no statistical difference between BCR and filtration LR on D1 of storage, but on D42, α-enolase concentration in the buffy coat sample, 12.2±1.4 ng/ml, was significantly increased versus 7.2 ± 0.7 ng/ml in those units that underwent filtration LR (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Peroxiredoxin-6 and α-enolase accumulate more in buffy-coat leukoreduced (BCR) samples during routine storage versus filtration LR.

Panel A. A representative immunoblot which demonstrates increased amounts of peroxiredoxin-6 present in BCR supernatant versus filtration (LR) from D1 and again on D42. Panel B. * indicates p< 0.05 from D1 within treatment and fMLF control and # indicates p<0.05 from filtration LR within day. Panel C. Concentrations of α-enolase determined by ELISA show an increase from D1 to D42 in both methods, but there is increased accumulation of α-enolase present in the BCR supernatant on storage D28 and 42. The mean densitometry for panel A calculated with ImageJ software; * indicates p < 0.05 from D1 within treatment, and # indicates p <0.05 within day.

Proteins identified in the supernatants from filtration and combination LR RBC units from D1 to D42 were identified and compared (Table 1 & 2). Peroxiredoxin-6 and peroxiredoxin-2 both showed a statistically significant increase from D1 to D42 in the two LR methods (n=5, p< 0.01), but when compared to one another, did not demonstrate a significant difference at the end of storage (Table 1). α-enolase concentrations also did not show any difference on same days of storage between filtration and combination LR. Both the α- and β-globin chains increased in the supernatants from D1 to D42 indicating that greater hemolysis occurred with RBC storage time. Combination LR, however, had a greater concentration of α–hemoglobin subunits than filtration LR (n=5, p<0.01). The same trend was seen with the β-hemoglobin subunits but did not achieve statistical significance (Table 1). Hemopexin, a scavenger for heme-containing compounds, was decreased during storage of both filtration and combination leukoreduction samples, but was significantly decreased in the supernatants from RBC units that underwent combination LR versus filtration LR on D42 (Table 2). These data indicate that there is an increase in hemolysis with storage time and is significantly greater in the supernatants from RBC units that underwent combination LR.

Table 1.

Proteins in supernatant demonstrating an increase from D1 to D42 of storage via QConCAT analysis.

| Protein Name | Protein Symbol | Day 1 (fM) | Day 42 (fM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Filtration | Combination | Filtration | Combination | ||

| Carbonic anhydrase 2 | CA2 | 6.0±1.3 | 12.7±5.7 | 45.4±7.3 | 69.9±15.6 |

| Catalase | CAT | 22.6±3.7 | 30.1±5.7 | 85.9±16.0 | 149.2±31.2 |

| Hemoglobin subunit alpha | HBA1 | 1856.6±250.2 | 2441.8±682.7 | 10064.5±1353.8†,‡ | 16717.4±2548.1†,‡ |

| Hemoglobin subunit beta | HBB | 3604.5±451.5 | 4807.0±933.9 | 12601.5±1172.4†,‡ | 18271.6±2672.3†,‡ |

| Hemoglobin subunit delta | HBD | 126.3±16.7 | 163.7±29.3 | 477.6±62.4 | 727.8±126.3 |

| Peroxiredoxin-1 | PRDX1 | 1.0±0.1 | 2.0±0.6 | 2.9±0.3 | 4.1±0.9 |

| Peroxiredoxin-2 | PRDX2 | 29.8±4.3 | 66.3±17.0 | 255.2±36.3† | 486.6±126.9† |

| Peroxiredoxin-6 | PRDX6 | 4.8±0.1 | 5.3±0.3 | 8.1±0.6* | 10.4±1.2† |

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

p < 0.01 from D1 within treatment,

p <0.05 from same day.

Table 2.

Proteins in supernatant demonstrate a decrease from D1 to D42 of storage via QConCAT analysis.

| Protein Name | Protein Symbol | Day 1 (fM) | Day 42 (fM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Filtration | Combination | Filtration | Combination | ||

| ApolipoproteinC-I | APOC1 | 326.5±60.7 | 346.3±46.7 | 225.5±43.8† | 168.6±36.4† |

| ApolipoproteinC-II | APOC2 | 146.8±38.1 | 161.6±36.6 | 120.5±30.1 | 78.9±19.6† |

| Ceruloplasmin | CP | 431.1±93.0 | 440.8±76.0 | 325.6±66.0 | 252.9±38.8* |

| Fibronectin-1 | FN1 | 56.5±15.7 | 69.3±8.7 | 51.5±5.7 | 43.5±4.7 |

| Glutathione peroxidase-3 | GPX3 | 36.2±0.9 | 35.0±3.2 | 25.7±1.0† | 20.0±2.0 |

| Hemopexin | HPX | 1269.4±52.7 | 1173.2±49.1 | 1046.9±30.5†,‡ | 843.6±39.5†,‡ |

| Retinol-binding protein-4 | RBP4 | 220.9±9.3 | 215.3±9.9 | 185.6±15.1 | 164.4±14.2 |

| L-selectin | SELL | 15.2±2.9 | 15.8±3.4 | 10.91±1.9 | 8.6±1.7† |

| Plasma protease C1 inhibitor | SERPING1 | 244.9±26.0 | 257.5±13.4 | 224.7±21.9 | 188.0±14.4 |

| Metalloproteinase inhibitor-1 | TIMP1_A | 5.9±0.7 | 4.7±0.3 | 4.8±0.6 | 3.8±0.3 |

| Metalloproteinase inhibitor-1 | TIMP1_B | 2.5±0.3 | 2.3±0.3 | 1.9±0.2 | 1.7±0.1 |

| Vitronectin | VTN | 331.1±22.5 | 312.1±33.6 | 265.5±23.7 | 191.2±9.8* |

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

p < 0.01 from D1 within treatment,

p <0.05 from same day.

Comparison of the priming activity that accumulates during storage in the supernatants of RBCs stored in AS-1, AS-3 or AS-5

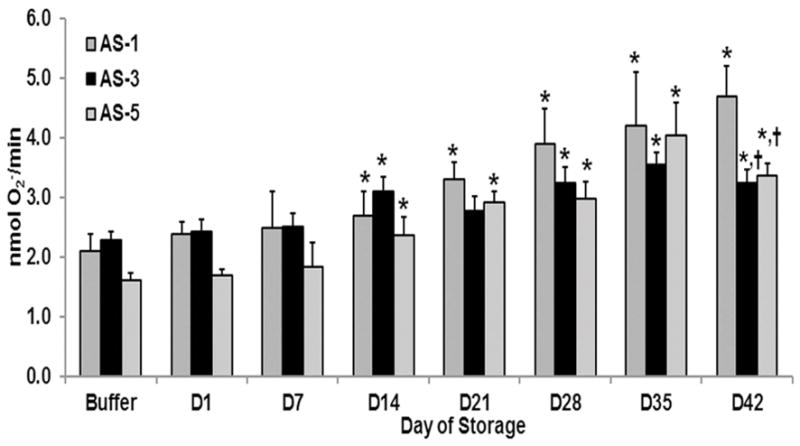

Because the data presented with respect to the three different methods of leukoreduction were limited to RBC units stored in AS-3, and leukoreduction by filtration yielded similar lipid priming activity to the combination LR method, the accumulation of PMN priming activity in the supernatant of LR-RBC units (filtration using the BPF4 filter) was assessed for units stored in AS-1 (20), AS-3 (20), and AS-5 (50) (Fig. 5). Importantly, a large portion of the priming activity of the supernatants from AS-1 or AS-5 stored RBCs have been previously reported and we have included some additional data from AS-1 or AS-5 RBC units. These units were drawn after obtaining informed consent and processed by the Manufacturing Division of Bonfils Blood Center using methods per the AABB and the FDA Circular of Information for the processing of leukoreduced RBC units.2,22,23,27 Supernatant priming for LR-RBCs stored in AS-1 demonstrated significant priming activity by D14 of storage, vs. buffer and fresh plasma (p<0.05), which increased with storage time and reached a relative maximum by storage outdate on D42, the last day the unit may be transfused (Fig. 5). The priming activity in the supernatant from LR-RBCs stored in AS-5 also became significant on D14, vs. buffer and fresh plasma (p<0.05), and increased over the storage interval reaching a maximum on D35 which persisted through D42 (Fig. 5). Lastly, the PMN priming activity in supernatants from LR-RBCs stored in AS-3 also became significant on D14 versus buffer or fresh plasma (p<0.05) which was not present on D21 and then reappeared on D28, which persisted throughout storage, D42 (Fig. 5). The D42 supernatant priming activity in the AS-3 and AS-5 LR-RBCs was significantly (p<0.05) less than the supernatant priming activity from the AS-1 LR-RBCs.

Figure 5. The effects of additive solutions on PMN priming activity in the supernatants of LR-RBCs through routine storage.

The maximal rate of SOD-inhibitable superoxide anion production is shown as a function of routine storage of LR-RBCs in different additive solutions: AS-1, AS-3 and AS-5. Supernatants from AS-1 stored LR-RBCs (intermediate gray bars) had significant PMN priming activity by D14, which continued throughout storage. The priming activity from the supernatants from AS-3 stored LR-RBCs (Black bars) was significant on day 14, disappeared on D21 and reappeared in the supernatants from D28–D42. The priming activity from the supernatants from AS-5 stored LR-RBCs (light gray bars) became significant on day 14 which persisted throughout routine storage. * indicates p<0.05 within treatment groups and buffer-treated controls and †= p<0.05 for the supernatant priming activity of AS-1 RBCs vs. AS-3 and AS-5.

Discussion

The implementation of leukoreduction has reduced the clinical frequency and severity of non-hemolytic febrile transfusion reactions, transmission of CMV, and the risk of HLA alloimmunization.1–6 The benefits of universal leukoreduction are no longer widely debated but the method of leukoreduction remains varied according to geographic implementation.28 Buffy coat LR, the predominant method used in developing countries like India, removes WBC by a single log.29 During routine storage, there was increased PMN priming activity in the buffy coat LR supernatants vs. D1 beginning on D7 and continuing until the end of storage with significantly higher amounts then either filtration or combination leukoreduction on days 28–42. Combination LR was no better than filtration LR and there was significantly more priming activity on D28 in the combination group and the supernatant priming activity was not different between the two methods of leukoreduction at the end of storage. Proteomics analysis demonstrated that both peroxiredoxin-6, a dual function protein with both peroxidase and phospholipase A2 activity, which increases during oxidant stress, and α-enolase were both increased in the buffy coat supernatants compared to the supernatants from the two leukoreduction methods.30 α-enolase is a glycolytic enzyme, a cellular plasminogen receptor, and has been implicated in acute lung injury through its ability to bind plasminogen to the cellular surface of monocytes.31 These data indicate that the buffy coat LR methodology is clearly inferior to the other methods because it caused increased release of intracellular proteins and increased accumulation of priming activity. The comparison of the PMN priming activity among stored RBC units using disparate additive solutions demonstrated that the supernatant from AS-1 stored units (n=20) accumulated more priming activity that was significant from D1 on D14 with maximal accumulation by D42 and significantly greater than the D42 supernatant priming activity in AS-3 or AS-5 LR-RBCs. The supernatants from AS-3 stored RBCs (n=20) had significant accumulation of PMN priming activity on D14, vs. D1, which was not present on D21, reappeared on D28, and persisted throughout D42. AS-5 (n=50) stored units demonstrated similar priming activity as AS-3 becoming significantly increased on D14 with priming persisting through D42.

Importantly, we did not control for the RBC losses due to processing amongst the groups. As indicated there was a 6–7% loss via BC removal, a 13% loss by filtration and an almost 19% loss for the combination LR methods. This loss is not RBCs alone because there is also loss of supernatant. Therefore, if there are fewer RBCs in those units that underwent combination LR then one would expect that less intracellular proteins, peroxiredoxin 1 and 6, the globin chains of hemoglobin, α-enolase, would appear over storage time not more as measured (Table 1). There was not a significant increase on Day 1 in those units that underwent LR by filtration versus LR by the combination methods. Similarly the priming activity was present in both the filtration LR RBCs and the combination LR units with activity that was not different in the LR combination which may have 6–7% less RBCs. Lastly, we used the standard Pall BPF4 for all filtration LR which may account for more losses of RBCs than combination LR methods employed in Canada and Europe. We did not control for the use of a smaller filter.

The cost of in-line filtration, however, is not trivial. Leukoreduction by filtration can add $100 USD to the cost of an RBC unit and is estimated to cost the USA at least $600 million/year.32 The combination method of buffy coat removal followed by filtration requires additional time, effort and cost of personnel but with uncertain increased benefit to the patient. Compared to LR by filtration alone, the combination method showed similar neutrophil priming activity and no statistical difference in accumulation of α-enolase or peroxiredoxin-2 and 6 via proteomic analysis on same days of storage. Furthermore, the greater accumulation of the α- and -β globin chains with decreased hemopexin levels indicated that more hemolysis occurred during storage following the combination LR method than filtration alone. Despite the greater cost and resources associated with combination LR and greater hemolysis of RBCs with manipulation, there is no difference in PMN priming activity and the accumulation proteins implicated in the development in TRALI or post-injury ALI.33

The leukoreduction data is from the supernatants of RBC units stored in AS-3 and one must not compare similar data from RBC units that employed AS-1, AS-5, or SAGM additive solutions. Similar to the previous studies using different additive solutions, an increase in PMN priming activity occurred during routine storage, from D1 to D42, irrespective of the LR methods used.22 Additional proteomic analysis of the RBC storage lesion in AS-3 additive solution has been completed and has demonstrated its ability to preserve RBC metabolism vs. SAGM, AS-1, and AS-5.15

Biologic response modifiers that accumulate during routine storage of cellular components have been linked to non-hemolytic transfusion reactions including TRALI.2,23,34–44 The two-event pathophysiology of TRALI requires a first event that elicits pro-inflammatory activation of the pulmonary microvascular endothelium which causes sequestration/adherence of PMNs which primes them.23,33,45,46 Priming of PMNs makes them hyper-reactive to a subsequent stimulus that normally does not activate PMNs in the “resting” state in the circulation.23,33,45,46 A second event occurs which activates these primed adherent PMNs resulting in endothelial damage, capillary leak, and ALI.23,33,45,46 This pathophysiology has been verified in animal models of TRALI to HLA class I and class II antibodies and to lipids, both lysophosphatidylcholines and non-polar lipids arachidonic acid, and 5-, 12-, and 15-hydroxyeicostetranoic acid.22,23,36,37,46 In one of the largest clinical series of clinical TRALI the implicated platelet units all had increased pro-inflammatory activity than those transfused to patients who did not experience a transfusion reaction.17 Thus, it was not the storage age of the product implicated that resulted in TRALI; rather, it was the amount of pro-inflammatory activity transfused.17

The two-event model of TRALI has been recently criticized because of the inability of volunteers injected with 2 ng/kg of E.coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to manifest TRALI when transfused with autologous PRBC units stored for 35 days.47 Injection of E.coli LPS induced fevers >38°C, pulses >90 beats/mins, and mild tachypnea (>20 breath/min) without evidence of pulmonary endothelial activation or PMN sequestration in the lung, a prerequisite for the two-event model of TRALI.46,48–50 In contrast, animals used for the two-event model of TRALI demonstrated fevers with rigors, copious diarrhea, and when sacrificed pulmonary sequestration of neutrophils.2,23,51 In addition, in tissue culture the activation of primary human, microvascular, endothelial cells (HMVECs) did not occur until LPS concentrations of 20 ng/ml are reached and such systems do not allow for the removal, modification or inactivation of LPS, which includes serum as part of the growth media.21 The concentrations of LPS that induced HMVEC activation in vitro were similar to those used as the first event in the two-event rodent model of TRALI.21,52,53 Moreover, two reported cases of self-administered LPS in which the individuals injected themselves with 2 μg and 1 mg of either E.coli or S.enteritides, respectively, became acutely ill with fevers, hypotension, gastroenteritis, increased respiratory rate, somnolence, and malaise.52–54 One of these patients had to be admitted to the intensive care unit with mild ALI and multi-organ dysfunction, which may have been due to overzealous resuscitation, and both survived.52–54 Importantly, in the pre-antibiotic era, the routine treatment of neuro-syphilis routinely employed injection of parenteral LPS, ≥1 mg, similar to that used in these two individuals, to the concentrations of LPS needed to activate human primary pulmonary endothelial cells in vitro, and as the first event in the animal model.21,23,46,52–54 Although animal modeling of human disease is never exact, it may be useful to understand in vivo relevance, and further experimentation, whether clinical or in animals, should be judiciously analyzed with comparable methodology.

Intravascular hemolysis leading to circulating plasma cell-free hemoglobin is a potential cause of oxidative injury in both normal patients and those with sickle cell disease (SCD).55–58 Plasma cell free hemoglobin has been linked to endothelial dysfunction, nephropathy and renal injury, especially in patients with SCD, and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).55–58 However, given the relatively low amounts of hemolysis observed in the RBC units that were leukoreduced by combination methodology, it is unlikely that the amount of plasma cell-free hemoglobin would result in endothelial dysfunction, renal damage, or ARDS outside of the setting of massive transfusion. ARDS is common post-injury, especially in those patients requiring massive RBC support and the possible effects of plasma cell free hemoglobin have not been delineated.59

There are a number of limitations in the presented data. The comparisons among the different methods of leukoreduction, both PMN priming and proteomics, are limited to a total of 10 units and only two methods of LR were compared head to head: BC removal to filtration and filtration to the combination method. Conversely the PMN priming data from the different additive solutions examined at least 20 units per additive solution with a total of 90 units examined over the entire storage interval. There is certainly donor variability; however, there was no difference amongst ABO blood groups for all were represented and yielded similar priming and proteomic results. In fact some of the highest priming activity was the supernatant from type O RBCs (data not shown). As the AS-3 additive solution has been shown through extensive metabolomics analysis that it preserves RBC metabolism for 14 days whereas other storage additives, e.g. SAGM, AS-1 and AS-5, did not.13–16 Despite better preservation of RBC metabolism, the PMN priming activity was present on D14 in AS-3 stored PRBC units, although it was not significantly increased on D21, reappeared on D28, and reached a relative maximum on D35, which persisted. In contrast, the supernatant priming activity in AS-1 stored RBC units reached a relative maximum on D42 which was increased versus RBC units stored in AS-3 and AS-5, and AS-3 and AS-5 RBC units reached maximal amounts of PMN supernatant priming activity on D28 which persisted through D42.15 The PMN priming activity from earlier storage times in AS-3 RBC units that disappears may be the result of filtration inducing the release of leukocyte and platelet intracellular proteins that disappear over storage.

Comparing rates of TRALI between populations using different leukoreduction methods is problematic due to underreporting and differing diagnostic criteria according to geographic location.1 In vitro neutrophil priming and detection of the proteins indicated in the pathophysiologic progress of TRALI imply that the combination method of leukoreduction, despite greater cost, is not superior to in-line filtration alone in minimizing risk of TRALI. Although in vivo head to head transfusions of the LR RBCs would be necessary to detect the clinical effects between the differing LR methods, our cellular and proteomic studies suggest that the LR combination method is not superior to in-line filtration and may compromise preservation and RBC recovery during storage due to increased hemolysis.

Transfusions are life-saving interventions and investigations on making the intervention safer and less costly are ongoing. Filtration alone provides optimal leukoreduction and minimization of biological response modifiers implicated in TRALI without increased manipulation of the RBCs. Additional metabolomic studies are needed and better additive solutions may further decrease the accumulation of biologic response modifiers and lessen the “storage lesion”. Experimental filtration, which removed immunoglobulins from RBCs, also significantly decreased bioactive lipid production, which may minimize the exposure of the transfused host, especially the critically ill, to pro-inflammatory mediators.2

Table 3.

Proteins in supernatant demonstrating no change from D1 to D42 of storage via QConCAT analysis.

| Day 1 (fM) | Day 42 (fM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Filtration | Combination | Filtration | Combination | ||

|

| |||||

| Annexin A5 | ANXA5 | 0.41±0.04 | 0.43±0.04 | 0.46±0.02 | 0.55±0.09 |

| Serum amyloid P-component | APCS | 57.4±7.3 | 54.8±6.0 | 50.8±6.8 | 46.1±3.4 |

| Apolipoprotein B-100 | APOB | 35.5±6.7 | 49.7±3.6 | 36.8±1.9 | 48.3±3.7 |

| Clusterin | CLU | 57.8±12.1 | 52.2±11.4 | 64.9±4.3 | 33.3±5.0 |

| Alpha-enolase | ENO1 | 0.015±0.002 | 0.027±0.011 | 0.019±0.003 | 0.021±0.003 |

| Filamin-A | FLNA | 0.4±0.0 | 0.5±0.1 | 0.5±0.1 | 0.4±0.0 |

| Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H1 | ITIH1 | 41.4±10.4 | 66.2±4.2 | 62.7±4.7 | 56.8±4.8 |

| Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2 | ITIH2 | 39.5±10.6 | 64.5±5.0 | 61.3±3.9 | 57.5±4.8 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase-9 | MMP9 | 6.5±0.7 | 6.9±0.6 | 6.2±0.5 | 5.3±0.3 |

| Protein S100-A8 | S100A8 | 2.2±0.2 | 2.8±1.4 | 2.1±0.7 | 1.4±0.2 |

| Vimentin | VIM | 4.2±0.2 | 4.2±0.1 | 4.3±0.1 | 4.1±0.3 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Acknowledgments

Grant Funding: 5 T32 CA 82086-15, NHLBI, NIH (MML), and support from P50 GM049222, NIGMS, NIH (MRK, CCS, MD and KCH), the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver (MD and KCH), and Bonfils Blood Center (MML, MRK, and CCS).

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest with the submitted manuscript

References

- 1.Silliman CC, Fung YL, Ball JB, Khan SY. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI): current concepts and misconceptions. Blood Rev. 2009 Nov;23(6):245–55. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silliman CC, Kelher MR, Khan SY, LaSarre M, West FB, Land KJ, Mish B, Ceriano L, Sowemimo-Coker S. Experimental prestorage filtration removes antibodies and decreases lipids in RBC supernatants mitigating TRALI in vivo. Blood. 2014 May 29;123(22):3488–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-532424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novotny VM, van DR, Witvliet MD, Claas FH, Brand A. Occurrence of allogeneic HLA and non-HLA antibodies after transfusion of prestorage filtered platelets and red blood cells: a prospective study. Blood. 1995 Apr 1;85(7):1736–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan SY, Kelher MR, Heal JM, Blumberg N, Boshkov LK, Phipps R, Gettings KF, McLaughlin NJ, Silliman CC. Soluble CD40 ligand accumulates in stored blood components, primes neutrophils through CD40, and is a potential cofactor in the development of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Blood. 2006 Oct 1;108(7):2455–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher M, Chapman JR, Ting A, Morris PJ. Alloimmunisation to HLA antigens following transfusion with leucocyte-poor and purified platelet suspensions. Vox Sang. 1985;49(5):331–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1985.tb00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenfeld L, Silver H, McLaughlin J, Klevjer-Anderson P, Mayo D, Anderson J, Herson V, Krause P, Savidakis J, Lazar A, et al. Prevention of transfusion-associated cytomegalovirus infection in neonatal patients by the removal of white cells from blood. Transfusion. 1992 Mar;32(3):205–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1992.32392213801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fung MA, Grossman BJ, Hillyer CD, Westhoff CM. Technical Manual. Bethesda: AABB; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gehrie EA, Dunbar NM. Modifications to Blood Components: When to Use them and What is the Evidence? Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016 Jun;30(3):653–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shukla R, Patel T, Gupte S. Release of cytokines in stored whole blood and red cell concentrate: Effect of leukoreduction. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2015 Jul;9(2):145–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.162708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glenister KM, Sparrow RL. Level of platelet-derived cytokines in leukoreduced red blood cells is influenced by the processing method and type of leukoreduction filter. Transfusion. 2010 Jan;50(1):185–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dzik S. Leukodepletion blood filters: filter design and mechanisms of leukocyte removal. Transfus Med Rev. 1993 Apr;7(2):65–77. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(93)70125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sparrow RL. Time to revisit red blood cell additive solutions and storage conditions: a role for “omics” analyses. Blood Transfus. 2012 May;10(Suppl 2):s7–11. doi: 10.2450/2012.003S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Alessandro A, D’Amici GM, Vaglio S, Zolla L. Time-course investigation of SAGM-stored leukocyte-filtered red bood cell concentrates: from metabolism to proteomics. Haematologica. 2012 Jan;97(1):107–15. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.051789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Alessandro A, Hansen KC, Silliman CC, Moore EE, Kelher M, Banerjee A. Metabolomics of AS-5 RBC supernatants following routine storage. Vox Sang. 2015 Feb;108(2):131–40. doi: 10.1111/vox.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Alessandro A, Nemkov T, Kelher M, West FB, Schwindt RK, Banerjee A, Moore EE, Silliman CC, Hansen KC. Routine storage of red blood cell (RBC) units in additive solution-3: a comprehensive investigation of the RBC metabolome. Transfusion. 2015 Jun;55(6):1155–68. doi: 10.1111/trf.12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roback JD, Josephson CD, Waller EK, Newman JL, Karatela S, Uppal K, Jones DP, Zimring JC, Dumont LJ. Metabolomics of ADSOL (AS-1) red blood cell storage. Transfus Med Rev. 2014 Apr;28(2):41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silliman CC, Boshkov LK, Mehdizadehkashi Z, Elzi DJ, Dickey WO, Podlosky L, Clarke G, Ambruso DR. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: epidemiology and a prospective analysis of etiologic factors. Blood. 2003 Jan 15;101(2):454–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BLIGH EG, DYER WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959 Aug;37(8):911–7. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silliman CC, Clay KL, Thurman GW, Johnson CA, Ambruso DR. Partial characterization of lipids that develop during the routine storage of blood and prime the neutrophil NADPH oxidase. J Lab Clin Med. 1994 Nov;124(5):684–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silliman CC, Dickey WO, Paterson AJ, Thurman GW, Clay KL, Johnson CA, Ambruso DR. Analysis of the priming activity of lipids generated during routine storage of platelet concentrates. Transfusion. 1996 Feb;36(2):133–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.36296181925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyman TH, Bjornsen AJ, Elzi DJ, Smith CW, England KM, Kelher M, Silliman CC. A two-insult in vitro model of PMN-mediated pulmonary endothelial damage: requirements for adherence and chemokine release. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002 Dec;283(6):C1592–C1603. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00540.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silliman CC, Moore EE, Kelher MR, Khan SY, Gellar L, Elzi DJ. Identification of lipids that accumulate during the routine storage of prestorage leukoreduced red blood cells and cause acute lung injury. Transfusion. 2011 Dec;51(12):2549–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelher MR, Masuno T, Moore EE, Damle S, Meng X, Song Y, Liang X, Niedzinski J, Geier SS, Khan SY, et al. Plasma from stored packed red blood cells and MHC class I antibodies causes acute lung injury in a 2-event in vivo rat model. Blood. 2009 Feb 26;113(9):2079–87. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Alessandro A, Dzieciatkowska M, Hill RC, Hansen KC. Supernatant protein biomarkers of red blood cell storage hemolysis as determined through an absolute quantification proteomics technology. Transfusion. 2016 Jun;56(6):1329–39. doi: 10.1111/trf.13483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bercovitz RS, Kelher MR, Khan SY, Land KJ, Berry TH, Silliman CC. The pro-inflammatory effects of platelet contamination in plasma and mitigation strategies for avoidance. Vox Sang. 2012 May;102(4):345–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2011.01559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dzieciatkowska M, Silliman CC, Moore EE, Kelher MR, Banerjee A, Land KJ, Ellison M, West FB, Ambruso DR, Hansen KC. Proteomic analysis of the supernatant of red blood cell units: the effects of storage and leucoreduction. Vox Sang. 2013 Oct;105(3):210–8. doi: 10.1111/vox.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Technical Manual. 16. Bethesda: American Association of Blood Banks; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bassuni WY, Blajchman MA, Al-Moshary MA. Why implement universal leukoreduction? Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2008 Apr;1(2):106–23. doi: 10.1016/s1658-3876(08)50042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma RR, Marwaha N. Leukoreduced blood components: Advantages and strategies for its implementation in developing countries. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2010 Jan;4(1):3–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.59384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6: a bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A(2) activities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 Aug 1;15(3):831–44. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miles LA, Ellis V. Alpha-enolase comes muscling in on plasminogen activation. Thromb Haemost. 2003 Oct;90(4):564–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shapiro MJ. To filter blood or universal leukoreduction: what is the answer? Crit Care. 2004;8(Suppl 2):S27–S30. doi: 10.1186/cc2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.West FB, Silliman CC. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: advances in understanding the role of proinflammatory mediators in its genesis. Expert Rev Hematol. 2013 Jun;6(3):265–76. doi: 10.1586/ehm.13.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan SY, Kelher MR, Heal JM, Blumberg N, Boshkov LK, Phipps R, Gettings KF, McLaughlin NJ, Silliman CC. Soluble CD40 ligand accumulates in stored blood components, primes neutrophils through CD40, and is a potential cofactor in the development of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Blood. 2006 Oct 1;108(7):2455–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silliman CC, Paterson AJ, Dickey WO, Stroneck DF, Popovsky MA, Caldwell SA, Ambruso DR. The association of biologically active lipids with the development of transfusion-related acute lung injury: a retrospective study. Transfusion. 1997 Jul;37(7):719–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37797369448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silliman CC, Voelkel NF, Allard JD, Elzi DJ, Tuder RM, Johnson JL, Ambruso DR. Plasma and lipids from stored packed red blood cells cause acute lung injury in an animal model. J Clin Invest. 1998 Apr 1;101(7):1458–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silliman CC, Bjornsen AJ, Wyman TH, Kelher M, Allard J, Bieber S, Voelkel NF. Plasma and lipids from stored platelets cause acute lung injury in an animal model. Transfusion. 2003 May;43(5):633–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heddle NM, Klama L, Singer J, Richards C, Fedak P, Walker I, Kelton JG. The role of the plasma from platelet concentrates in transfusion reactions. N Engl J Med. 1994 Sep 8;331(10):625–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409083311001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kristiansson M, Soop M, Saraste L, Sundqvist KG. Cytokines in stored red blood cell concentrates: promoters of systemic inflammation and simulators of acute transfusion reactions? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1996 Apr;40(4):496–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1996.tb04475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakamoto S, Fujihara M, Kuzuma K, Sato S, Kato T, Naohara T, Kasai M, Sawada K, Kobayashi R, Kudoh T, et al. Biologic activity of RANTES in apheresis PLT concentrates and its involvement in nonhemolytic transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 2003 Aug;43(8):1038–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen R, Escorcia A, Tasmin F, Lima A, Lin Y, Lieberman L, Pendergrast J, Callum J, Cserti-Gazdewich C. Feeling the burn: the significant burden of febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 2017 Jul;57(7):1674–83. doi: 10.1111/trf.14099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blumberg N, Spinelli SL, Francis CW, Taubman MB, Phipps RP. The platelet as an immune cell-CD40 ligand and transfusion immunomodulation. Immunol Res. 2009 Dec;45(2–3):251–60. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8106-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cognasse F, Payrat JM, Corash L, Osselaer JC, Garraud O. Platelet components associated with acute transfusion reactions: the role of platelet-derived soluble CD40 ligand. Blood. 2008 Dec 1;112(12):4779–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heddle NM. Pathophysiology of febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions. Curr Opin Hematol. 1999 Nov;6(6):420–6. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199911000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silliman CC. The two-event model of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2006 May;34(5 Suppl):S124–S131. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000214292.62276.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelher MR, Banerjee A, Gamboni F, Anderson C, Silliman CC. Antibodies to major histocompatibility complex class II antigens directly prime neutrophils and cause acute lung injury in a two-event in vivo rat model. Transfusion. 2016 Dec;56(12):3004–11. doi: 10.1111/trf.13817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peters AL, van Hezel ME, Cortjens B, Tuip-de Boer AM, van BR, de KD, Jonkers RE, Bonta PI, Zeerleder SS, Lutter R, et al. Transfusion of 35-Day Stored RBCs in the Presence of Endotoxemia Does Not Result in Lung Injury in Humans. Crit Care Med. 2016 Jun;44(6):e412–e419. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelher MR, Masuno T, Moore EE, Damle S, Meng X, Song Y, Liang X, Niedzinski J, Geier SS, Khan SY, et al. Plasma from stored packed red blood cells and MHC class I antibodies causes acute lung injury in a 2-event in vivo rat model. Blood. 2009 Feb 26;113(9):2079–87. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peters AL, Vervaart MA, van Bruggen R, de Korte D, Nieuwland R, Kulik W, Vlaar AP. Non-polar lipids accumulate during storage of transfusion products and do not contribute to the onset of transfusion-realted acute lung injury. Vox Sang. 2016 doi: 10.111/vox12453:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters AL, van Hezel ME, Klanderman RB, Tuip-de Boer AM, Wiersinga WJ, van der Spek AH, van BR, de KD, Juffermans NP, Vlaar APJ. Transfusion of 35-day-stored red blood cells does not alter lipopolysaccharide tolerance during human endotoxemia. Transfusion. 2017 Jun;57(6):1359–68. doi: 10.1111/trf.14087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kelher MR, Ambruso DR, Elzi DJ, Anderson SM, Paterson AJ, Thurman GW, Silliman CC. Formyl-Met-Leu-Phe induces calcium-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Rel-1 in neutrophils. Cell Calcium. 2003 Dec;34(6):445–55. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sauter C, Wolfensberger C. Interferon in human serum after injection of endotoxin. Lancet. 1980 Oct 18;2(8199):852–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taveira da Silva AM, Kaulbach HC, Chuidian FS, Lambert DR, Suffredini AF, Danner RL. Brief report: shock and multiple-organ dysfunction after self-administration of Salmonella endotoxin. N Engl J Med. 1993 May 20;328(20):1457–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hurley JC. Self-administration of Salmonella endotoxin. N Engl J Med. 1993 Nov 4;329(19):1426–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Janz DR, Ware LB. The role of red blood cells and cell-free hemoglobin in the pathogenesis of ARDS. J Intensive Care. 2015;3:20. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0086-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Zhi H, Yuen PS, Star RA, Banks SM, Schechter AN, Natanson C, Gladwin MT, Solomon SB. Hemolysis-associated endothelial dysfunction mediated by accelerated NO inactivation by decompartmentalized oxyhemoglobin. J Clin Invest. 2005 Dec;115(12):3409–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI25040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saraf SL, Zhang X, Shah B, Kanias T, Gudehithlu KP, Kittles R, Machado RF, Arruda JA, Gladwin MT, Singh AK, et al. Genetic variants and cell-free hemoglobin processing in sickle cell nephropathy. Haematologica. 2015 Oct;100(10):1275–84. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.124875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bastarache JA, Roberts LJ, Ware LB. Thinking outside the cell: how cell-free hemoglobin can potentiate acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014 Feb;306(3):L231–L232. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00355.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sauaia A, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Chin TL, Banerjee A, Sperry JL, Maier RV, Burlew CC. Temporal trends of postinjury multiple-organ failure: still resource intensive, morbid, and lethal. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014 Mar;76(3):582–92. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000147. discussion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]