Abstract

Background and purpose:

Aerobic exercise is as important for individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI) as for the general population, however the approach to aerobic training may require some adaptation. The objective of the trial programwas to examine the feasibility of introducing aerobic physical exercise programs into the subacute phase of multidisciplinary rehabilitation from moderate-to-severe TBI, which includes computerized cognitive training.

Case description:

Five individuals undergoing inpatient rehabilitation with moderate or severe TBIs who also have concomitant physical injuries. All of these individuals were in the subacute phase of recovery from TBIs.

Intervention:

An 8-week progressive aerobic physical exercise program. Participants were monitored to ensure that they could both adhere to and tolerate the exercise program. In addition to the physical exercise, individuals were undergoing their standard rehabilitation procedures which included cognitive training. Neuropsychological testing was performed to gain an understanding of each individuals’ cognitive function.

Outcomes:

Two minor adverse events were reported. Participants adhered to both aerobic exercise and cognitive training. Poor correlations were noted between heart rate reserve and ratings of perceived effort.

Discussion:

Despite concomitant injuries and cognitive impairments, progressive aerobic exercise programs seem feasible and well tolerated in subacute rehabilitation from moderate-to-severe TBI. Some findings highlight the difficulty in measuring exercise intensity in this population. Video Abstract available for more insights from the authors (see Video, Supplemental Digital Content)

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) may be associated with behavioral, sensorimotor and cognitive deficits, which result in significant social, personal and economic burdens. Cognitive impairment is an important statistical predictor of return to work1 and with a mere 40% of individuals with severe TBI returning to work within 1-year of injury,2 long-term treatments aimed at combating these deficits are critical for quality of life. Aerobic exercise, an inexpensive, easily administered and potentially long-term therapeutic intervention has been shown to have many physiological, structural and cognitive effects on the brain.3–7 In non-injured adults, aerobic exercise appears to have beneficial effects on a variety of cognitive functions including attentional processes8 and executive functions such as working memory and task switching.9,10 In clinical studies improved attention, delayed memory and executive functions 11,12 have been observed in individuals with traumatic brain injury who participated in aerobic exercise. Additionally, a cardiorespiratory benefit of aerobic exercise in individuals with TBI has been shown.13,14 A recent systematic review on aerobic exercise and cognitive recovery after TBI 15 highlighted some shortcomings inherent in these studies, including grouping together of individuals in different phases of recovery (subacute and chronic) and inadequate information on multidisciplinary rehabilitation procedures. Moreover, cognitive impairment and concomitant physical injuries may limit the participation in, and adherence to, an aerobic exercise program.

Common concomitant injuries associated with TBI include musculoskeletal injuries 16 and gait and balance impairments.17 apraxia and/or hypokinesia,18 pain19 and spasticity20. These conditions may constitute barriers to aerobic exercise, especially in the subacute phase of injury. It is possible that the duration, intensity and frequency needed to induce an adaptive plastic response to enhance functional and cognitive recovery may not be achieved in individuals who present with severe secondary conditions. It has been suggested that individuals with TBI have poor awareness of subjective fatigue however,21 Assessing the feasibility of measuring and controlling for exercise parameters such as frequency, duration and intensity, is therefore important.

Inpatient as well as early outpatient rehabilitation for TBI includes intensive sessions of physical therapy, occupational therapy, behavioral speech therapy and cognitive rehabilitation. This multidisciplinary approach means outcomes are unlikely to be influenced greatly by any single therapeutic approach.22 Meta-analyses on cognitive rehabilitation outcomes suggest computerized cognitive training is beneficial for improving cognitive functions such as executive function and attention 23,24 and is a common therapeutic tool in neurorehabilitation clinics 25. Research has postulated that the combination of aerobic exercise with cognitive training may be more effective than either one alone 26. Since fatigue 27 and apathy 28 are common symptoms in subacute TBI, the addition of aerobic exercise to traditional rehabilitation may pose challenges regarding the adherence to both programs. Should both interventions prove efficacious, it is important that individuals can participate in both. Therefore, the development of successful aerobic exercise programs early after TBI requires the assessment of their feasibility. The aim of this case series was to assess the feasibility of the inclusion of an 8-week progressive aerobic exercise program in addition to standard multidisciplinary rehabilitation, which includes computerized cognitive training, for persons with moderate-to-severe TBI who were in the subacute phase of recovery.

Case descriptions

Participants were recruited from an acquired brain injury inpatient unit and were assessed by both a trained neuropsychologist and physical therapist to assure they met the inclusion criteria for inclusion. Participants were considered eligible to participate in thisprogram if they: i) had a diagnosis of moderate or severe TBI (3–8 or 9–13 on the Glasgow Coma Scale, respectively 30) ii) had sufficient cognitive ability to understand written and verbal instructions (>6 on the Rancho Los Amigos Scale 31); and iii) if they no longer displayed post-traumatic amnesia (measured by an average score of >75 on the Galveston Orientation Amnesia Scale over 3 consecutive days). Participants were excluded from the if they had a history of a previous moderate or severe TBI, if they presented with any neurological or cardiorespiratory complications that were a contraindication to perform physical exercise, as described by the American College of Sports Medicine 32 or if they presented with aphasia, which would limit their ability to perform the cognitive assessments and program procedures. The education and ethics committee of _______approved this protocol. All participants signed an informed consent prior to enrollment. The informed consent documents were left with the participant and family members overnight and family members were active in all consent processes.

The demographics of five individuals with moderate or severe TBI who were undertaking inpatient rehabilitation at the time of recruitment are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Participant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19 | 56 | 34 | 43 | 32 |

| Gender | M | M | M | M | M |

| Severity of Injury (GCS) | Severe (4) |

Moderate (10) |

Severe (3) |

Moderate (11) |

Severe (5) |

| Pre-intervention resting HR |

58 | 79 | 67 | 58 | 58 |

| Time since injury (days) | 91 | 24 | 30 | 51 | 48 |

| PTA time (days) | 78 | 24 | 18 | 36 | 38 |

| Cause of injury | Skiing accident | Traffic accident | Traffic accident | Traffic accident | Traffic accident |

| Concomitant injuries / barriers to exercise | Complete loss of independent ambulation, Apraxia / ataxia | C4 vertebral fracture | Brachial plexus injury / fractured clavicle / chronic pain | n/a | Rib fractures 10/11 |

| Pre-injury activity level | Active | Active | Active | Active | Active |

GCS, Glasgow coma score; PTA, post traumatic amnesia

Participant 1 was a 19-year-old male who collided at high velocity with a wooden shed while skiing. He was wearing a helmet at the time but the impact caused the helmet to break apart. He lost consciousness immediately and upon being admitted to the hospital was awake but minimally conscious. His injury resulted in gait impairments including ataxia and apraxia. He had been an active adult prior to the injury, participating in regular sport and activity. At the time of the accident, Participant 1 was in the first year of undergraduate studies in computer engineering and spoke four languages.

Participant 2 was a 56-year-old male who sustained a head injury in a motorcycle accident. He lost control of the motorcycle and was subsequently hit by a moving car. He presented with concomitant injuries of a cervical fracture at C4. He had been an active adult prior to injury participating in cycling multiple days per week; he had vocational training in auto mechanics.

Participant 3 was a 34-year old male who sustained a head injury in a motor cycle accident. He fell from his motorcycle and hit the pavement with his head, breaking his helmet. He sustained a brachial plexus injury to the right arm, which caused severe pain as well as cervical compression myelopathy and a fractured right clavicle. He was an active adult prior to his injury participating in sport and resistance exercises multiple times per week,and worked as a computer engineer.

Participant 4 was a 43-year-old male who sustained a head injury caused by a fall. He was found with anisocorous pupils with mydriasis of the right pupil. An urgent craniotomy on the right side was performed. He sustained no concomitant injuries as a result of his accident. He was active prior to his injury participating in sport and exercise multiple times per week.

Participant 5 was a 32-year-old male who sustained a head injury due to a collision with a motor vehicle while riding a bicycle. He presented with concomitant injuries consisting of atelectasis contusion in the left posterobasal pulmonary segments associated with mild hemothorax and fractures of the posterior costal arches of ribs 10 and 11. He was physically active prior to the injury.

Intervention

All participants began the program as inpatients and were discharged from the hospital during the 8-week intervention period. Participants 1, 2, and 3 returned as outpatients to continue their rehabilitation and the program whereas Participants 4 and 5 did not live in the local area and did not return for treatment in the outpatient clinic.

Description of rehabilitation procedures

All participants were undergoing standard and individualized multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs throughout the entire program period, which involved intensive 5 hours a day, 5–7 days a week of occupational therapy, physical therapy, and behavioural speech therapy. Functional testing using standardized outcome measures was completed on all participants, however, those measures are not within the scope of this report. Cognitive training using a computerized cognitive training platform (Guttmann NeuroPersonal Trainer, Barcelona, Spain) was performed by each participant at a similar frequency to the physical exercise (three times per week for one hour during the 8-week program period). The cognitive training consists of a set of computerized cognitive tasks that cover different cognitive functions (attention, memory and executive functions) and sub-functions;for a full list of sub-functions see Solana et al25. A baseline neuropsychological assessment was used to determine the cognitive training program (ie, which tasks, at what frequency and at what difficulty level to begin) and an automated algorithm, ‘Intelligent therapy assist’ 33 continuously monitored and updated the individual’s progress.

Measures of neuropsychological function

Participants were administered a battery of clinical neuropsychological tests by a trained neuropsychologist prior to (<1-week) the 8-week intervention period. The Trail Making Test A 34, where the participant was instructed to connect 25 numbered dots consecutively, as quickly and accurately as possible was used as a measure of processing speed and attention. The digit span forward, digit span backward and letter/numbers tests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Part III (WAIS 35), a series of tests during which the participant was read a series of numbers (or numbers and letters for letters/numbers) and asked to repeat them in the same order, or backwards were undertaken and which have been asserted to measure working memory. The Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Tests (RAVLT 36) which measures episodic memory using a word-list learning task where 15 unrelated words are verbally presented and the participant was asked to recall as many as possible was performed. Five trials were presented which give measures of immediate word span (short term) and after a 20 minute delay, long-term recall. A second list was read and the participant was required to indicate whether a word was from the original list or a new list (retention). The block design task from the WAIS, which measures visual abstract processing, spatial perception and problem solving, was also administered. The participant was presented with red and white blocks (with two red sides and two white) and was asked to construct replicas of designs previously presented by the examiner. Lastly, the verbal fluency task (FAS 37) was administered, this task consists of three word-naming trials wherein the participant is instructed to say as many words beginning with a given letter of the alphabet (typically F A or S although in this program P M and R were used as part of the Spanish language version 38).

Progressive aerobic exercise program

Before the start of the intervention an introductory session was provided to familiarize participants with the equipment and aerobic exercise program. The participants performed the aerobic exercise activities 3 times per week for 8 weeks. The exercise equipment used for aerobic training by each of the participant was selected as indicated by initial functional status. Two machines were available: an active/passive exercise trainer that delivered resistance for active exercising of the arm, leg or arms and legs (Motomed Muvi, RECK, Betzenweiler, Germany), and an upright cycle ergometer (Keiser M3 indoor, Fresno, CA). If the participant was non-ambulatory training began with the active/passive trainer, with the participant performing arm cycling only. Weekly assessments by the participant’s physical therapist determined whether progression from active/passive arm cycling to both arm and leg cycling or to the cycle ergometer was appropriate. Decisions were based on functional capacity of the participant, e.g achieving sufficient leg strength to perform active leg cycling, regaining sufficient lower extremity control and balance to ride the cycle ergometer.

The target exercise intensity zone was defined as 50–70% of heart rate reserve (HRR). The corresponding heart rate (HR) in beats per minute (BPM) was calculated using the Karvonen equation ([220-age]-resting heart rate * intended goal % of HRR + heart rate rest) and monitored continuously by a wrist-based photoplethysmographic heart rate monitor (Polar A380, Polar Electro, Kemple, Finland). Nursing staff recorded resting heart rate periodically during the early mornings, according to standard hospital protocol, and the average of the three lowest values in the three days prior to enrolment in program was recorded as pre-intervention resting heart rate. Ratings of perceived exertion using the 6–20 Borg scale of perceived exertion 39 were taken every 15-minutes; this scale is a widely used with both verbal anchors and corresponding numbers whereby 6 represents “no exertion at all” and 20 represents “maximal effort”. The scale is based on the physical sensations a person experiences during exercise, including increases in HR. A high correlation between the numerical anchors (times by 10) and actual heart rate during exercise has been shown 40.The target HR zones of 50–70% of HRR are said to correspond to 12–14 (“somewhat hard”) on this scale 32.

Each aerobic exercise session was designed to last between 45 – 60 minutes with a 10-minute warm-up and cool-down included in each session. Warm-up sessions consisted of light resistance exercise. The exercise protocol was devised to allow each participant to become familiar with aerobic exercise, thus initially, participants were asked to undertake exercise at their own pace and were allowed to stop at any time. After completing week 1, the physical therapists asked participants to attempt to progressively increase their exercise intensity (as measured by HR) and the duration of each session until they reached a consistent performance in each session that comprised 25 – 35 minutes of aerobic exercise within the target HRR zone. As patient engagement in health care may lead to improved outcomes41 physical therapy staff used verbal encouragement and positive feedback to promote participant engagement and to motivate them to be involved in increasing the resistance of the exercise. The physical therapists monitored the participants HR and RPE to ensure intensity was increased in a progressive manner (i.e. not abruptly). A decision diagram of the aerobic exercise program is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the progressive aerobic exercise intervention

Outcome measures

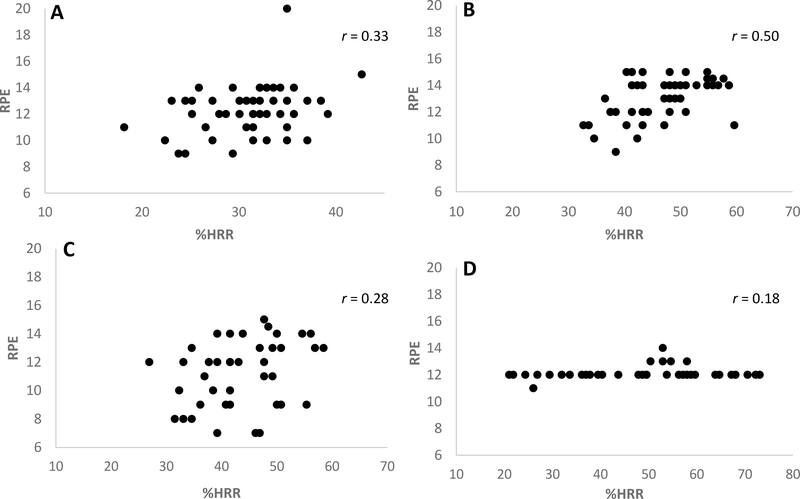

Feasibility was measured using the following outcomes: number of adverse events reported, adherence to the aerobic exercise program (session durations and number of session attended), time spent in HRR training zones, the correlation between RPE and HRR and adherence to the cognitive rehabilitation training program (number of sessions attended and tasks performed).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using graphing and statistics software (GraphPad Prism 7.00 for Macintosh, GraphPad software, La Jolla California, USA) Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for the relationship between RPE and HRR. HRR was measured as the average HRR (calculated from bpm using the Karvonen equation) in the 30-seconds before and after the measurement of RPE at 15-minute intervals. Heart rate in beats per minute was recorded second-by-second and time spent in HRR training zones calculated by the amount of time (seconds) each participants’ corresponding heart rate was at or above individual 50% HRR.

Outcomes

The neuropsychological profile of each participant at the beginning of the intervention is shown in Table 2. All participants had significant executive function deficits and varying degrees of working memory and verbal memory deficits. Two adverse events were reported during the program. Participant 1 complained of feelings of nausea during one session and Participant 2 complained of feeling light-headed after one session within the first week. Throughout the program period no participant took beta-blockers or any other antiarrhythmic medications or medications that directly affect heart rate. Three participants (1, 2, 3) were being treated with benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications, which could be associated with adverse effects on heart rate but all participants were prescribed the recommended dosages and no adverse events were reported. Participant 1 was taking clonidine but no side effects related to heart rate were reported.

Table 2.

Neuropsychological test scores

| Participant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | ||||||||||

| RAVLT Short term (verbal memory) | 28 | VS | 33 | M | 34 | VS | 42 | S | 20 | VS |

| RAVLT long term (verbal memory) | n/a* | VS | 5 | M | 1 | M | 8 | S | 2 | VS |

| RAVLT retention (verbal memory) | n/a* | VS | 12 | N | 9 | M | 12 | S | 5 | VS |

| WAIS digit span forward (short term memory) | 6 | N | 4 | S | 6 | N | 6 | N | 5 | S |

| WAIS digit span backwards (working memory) | 7 | N | 4 | N | 4 | N | 5 | N | 3 | S |

| WAIS letters/numbers (working memory) | 5 | S | 10 | N | 11 | N | 8 | S | n/a* | VS |

| WAIS block design (visual construction) | n/a^ | 26 | N | 46 | N | 27 | M | 15 | S | |

| TMT-A (attention) | 77 | VS | 84 | S | 56 | N | 31 | N | 57 | M |

| FAS (executive function) | 20 | VS | n/a* | VS | 20 | VS | 19 | VS | 16 | VS |

Left column = test score, right column = level of deficit, based on age and level of education: VS = very severe, S = severe, M = moderate, N = normal. RAVLT, Rey auditory verbal learning test; WAIS, Wechsler adult intelligence scale; TMT-A, trail making test part A; FAS, phonemic verbal fluency test.

n/a, participant unable to complete test due to severe deficit

n/a, participant unable to complete test due to motor impairment.

Feasibility data from the aerobic exercise program is shown in Table 3. Adherence percentages are presented as % of 15 sessions for Participants 4 and 5. All participants had adherence rates above 80% to the cognitive training program except Participant 4 (73%). Participant 4 and 5 spent 55% and 56%, respectively, of the aerobic exercise program within the target heart rate zone. Participant 2 spent 4% of his time within the target zone, with a mean HRR of 40% over all sessions. Participants 1 and 3 did not exercise within the target zone for any amount of time during the 8-week program. Individual mean %HRR obtained in 15-minute increments shown in Figure 2. RPE values for Participant 5 were not collected due to investigator error and therefore are missing. Figures 3A-D displays mean individual plots of % HRR and RPE every 15 minutes for Participants 1–4 over course of the 8-week program. Pearson correlation coefficients indicated low correlation between HRR and RPE in all participants (Participant 1, r = 0.33; Participant 2, r = 0.5; Participant 3, r = 0.28; Participant 4, r = 0.17).

Table 3.

Feasibility data from the aerobic exercise and cognitive training programs

| Participant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic exercise | |||||

| Total number of sessions | 24 | 23 | 23 | 12 | 13 |

| % adherence | 100% | 95% | 95% | 80% | 87% |

| Mean session duration (mins) | 45 | 47 | 41 | 45 | 49 |

| Mean % HRR | 33% | 40% | 40% | 55% | 56% |

| Mean time spent in HRR training zone (%) | 0 | 4% | 0% | 55% | 62% |

| Mean BPM | 102 | 109 | 108 | 116 | 128 |

| Mean RPE | 12 | 13 | 11 | 12 | |

| Cognitive training | |||||

| Total number of sessions | 24 | 24 | 24 | 11 | 12 |

| % adherence | 100% | 100% | 100% | 73% | 80% |

| # tasks performed | 363 | 222 | 252 | 157 | 234 |

% adherence based on 24 sessions for Participants 1, 2 and 3 and on 15 sessions for Participants 4 and 5. HRR, heart rate reserve; BPM, beats per minute; RPE, ratings of perceived exertion.

Figure 2.

Individual mean %HRR at 15-minute intervals (1 minute average of HRR before and after each 15-minute mark) with standard error bars. Key indicates graph for each Participant (P) 1–4.

Figure 3 A -D.

Scatter plots for individual mean %HRR and mean RPE at 15-minutes intervals with Pearson correlation coefficient values for Participants 1–4 over the course of the 8-week program. A, Participant 1; B, Participant 2; C, Participant 3; D, Participant 4;.

DISCUSSION

This case series aimed to assess the feasibility of introducing progressive aerobic exercise programs into subacute rehabilitation of moderate-to-severe TBI. Despite cognitive impairments and concomitant physical injuries, participants adhered to the exercise program with no serious adverse events. Nevertheless, only 2 of the 5 participants exercised for more than 50% of the time within the target heart rate zones and poor correlations between HRR and perception of effort were observed.

Inpatient as well as early outpatient rehabilitation for individuals with severe TBI involves intensive multidisciplinary interventions. However, damage to frontal lobes and networks integral to drive and motivation can be problematic to the rehabilitation process 42. Low motivation in individuals with TBI is often observed and commitment to, and perseverance in, rehabilitation can be negatively affected 43. Fatigue 27 and apathy 28 are also common in this phase of recovery and so, aerobic exercise may be challenging to initiate and sustain. More recently, adherence to minimally supervised aerobic exercise programs within community-dwelling individuals with TBI was deemed feasible 44. Importantly, such aerobic exercise programs may improve mood in chronic TBI 45,46. Less is known about adherence to aerobic exercise in sub-acute rehabilitation however, and so the results reported here suggest the addition 1-hour sessions of aerobic exercise 3 times per week for 8-weeks to the multidisciplinary rehabilitation schedule can be feasible.

Up to 78% of individuals with TBI may have concomitant extracranial injuries, which have been significantly associated with long-term disability 47. These physical barriers to aerobic exercise can also contribute to a sedentary lifestyle and result in long-term sedentary behaviour upon discharge from the hospital 48. Therefore, the re-introduction of aerobic exercise soon after injury may be important. Indeed, aerobic exercise has been shown to improve clinical disability scores in other clinical populations 49 and so successful adherence to an early 8-week aerobic exercise program in individuals with concomitant injuries to TBI, such as loss of ambulation (Participant 1), cervical and clavicle and rib fractures (Partcipants 2, 3 and 5) has the potential to improve long term disability. Nevertheless, despite adhering to both the exercise program and traditional rehabilitation, only two participants (Participants __ and ___) exercised for more than 50% of the time within the target intensity zones. A previous study showed that just 28% of individuals with severe TBI exercised above 50% of their heart rate reserve (HRR) during circuit class therapy 13. The authors did not report on physical limitations of participants in that study. It is possible that the concomitant injuries sustained by the participants in this case series limited their ability to exercise at higher HR intensities. Variables beyond physical limitations (which dictated exercise type) may also account for failure to achieve the target training intensity. Participants Participants 1 and 2 performed different exercises (arm/leg cycling and static upright cycling, respectively) and neither participant exercised within the target HR training zones. The Karvonen equation, which was used to calculate HR training zones, uses 220 minus age to predict HR maximum and may be a contributing factor. The peak aerobic capacity of individuals with TBI has been reported at 65–74% of non-injured adults 50–52 and so this widely used equation may overestimate intensity zones in this population.

The possible inability of the Karvonen equation to capture true HRR in individuals who have lower peak aerobic capacity could also explain the poor correlation between HRR and RPE seen. However, participant Participant 4 reported the same RPE value at most time points regardless of HR making it likely that this individual had difficulty in accurately perceiving his true effort. Indeed poor awareness of subjective fatigue in individuals with TBI compared to healthy controls has previously been reported 21. Importantly, the Borg scale has not been validated in individuals with TBI and discrepancies in the meaning of the verbal anchors may exist in this population 53. Nevertheless, RPE is the preferred method to assess intensity in individuals who take medications that affect HR or pulse 54. The need to accurately perceive exertion is of particular importance because if the peak aerobic capacity of individuals with TBI is reduced 50–52 and/or medications that affect resting heart rate are taken, then heart rate measures to control for the intensity of exercise may be invalid. Yet the use of RPE may also prove inaccurate 53,55. Larger studies to assess this perceived HR in individuals in the subacute phase of TBI recovery and a search for optimal methods to account for exercise intensity are needed.

Limitations

The outcomes of this case series should be interpreted in light of the limitations. Beyond the limitations of using RPE in persons with subacute TBI, the recording of RPE at 15-minute intervals in a small sample may have been too infrequent, yet RPE assessment at greater frequencies within the clinic may be impractical. The value of using wrist-based photoplethysmograpghy (PPG) technology to monitor HR is uncertain due to its susceptibility to motion artifact,56 however, these may represent the best option as the use of the chest straps (currently the gold standard) may be impractical in individuals with severe TBI who present with behavioral and cognitive impairments. Additionally, by not re-measuring resting heart rate prior to each exercise session it is not possible to account for changes in resting heart rate (which dictates heart rate training zones) over the 8-week intervention period.

Summary

The inclusion of 1-hour sessions of aerobic exercise three times weekly in an 8-week intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation was feasible for participants with moderate-to-severe TBI. Individuals tolerated the aerobic exercise well and concomitant physical injuries did not hinder their participation. Despite this feasibility, future studies are required to better understand how the intensity of exercise can be measured and accounted for in this population.

Supplementary Material

SDC 1: Video Abstract

Acknowledgments:

We extend our thanks and gratitude to Dr. Josep Medina Casanova (Institut Guttmann), Dr Alberto Garcia Molina (Institut Guttmann) and Dr. Antonia Enseñat Cantallops (Institut Guttmann) for their help during the running of this program. We extend our thanks to Dr Alexandra M. Stillman (BIDMC) for her guidance in the preparation of this manuscript.

sources of funding: In part supported by the Barcelona Brain Health Initiative. Dr. A. Pascual-Leone was partly supported by the Sidney R. Baer Jr. Foundation, the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University, and Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NCRR and the NCATS NIH, UL1 RR025758). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, the National Institutes of Health, or the Sidney R. Baer Jr. Foundation. Dr. A. Pascual-Leone is listed as an inventor on several issued and pending patents on the real-time integration of transcranial magnetic stimulation with electroencephalography and magnetic resonance imaging.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest This project did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Benedictus MR, Spikman JM, van der Naalt J. Cognitive and Behavioral Impairment in Traumatic Brain Injury Related to Outcome and Return to Work. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(9):1436–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Velzen JM, van Bennekom CAM, Edelaar MJA, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MHW. How many people return to work after acquired brain injury?: a systematic review. Brain Inj. 2009;23(6):473–488. doi: 10.1080/02699050902970737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, Kim JS, Heo S, Alves H, White SM, Wojcicki TR, Mailey E, Vieira VJ, Martin SA, Pence BD, Woods JA, McAuley E, Kramer AF. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):3017–3022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oberlin LE, Verstynen TD, Burzynska AZ, Voss MW, Shaurya R, Chaddock-heyman L, Wong C, Fanning J, Awick E, Gothe N, Phillips SM, Mailey E, Ehlers D, Olson E, Wojcicki T, Mcauley E, Kramer AF, Erickson KI. White matter microstructure mediates the relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and spatial working memory in older adults ☆. NeuroImage. 2016;131:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sexton CE, Betts JF, Demnitz N, Dawes H, Ebmeier KP, Johansen-berg H. A systematic review of MRI studies examining the relationship between physical fi tness and activity and the white matter of the ageing brain. NeuroImage. 2016;131(August 2015):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.09.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas AG, Dennis A, Rawlings NB, Stagg CJ, Matthews L, Morris M, Kolind SH, Foxley S, Jenkinson M, Nichols TE, Dawes H, Bandettini PA, Johansen-berg H. Multi-modal characterization of rapid anterior hippocampal volume increase associated with aerobic exercise ☆. NeuroImage. 2016;131:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voss MW, Heo S, Prakash RS, Erickson KI, Alves H, Chaddock L, Szabo AN, Mailey EL, Wójcicki TR, White SM, Gothe N, McAuley E, Sutton BP, Kramer AF. The influence of aerobic fitness on cerebral white matter integrity and cognitive function in older adults: Results of a one-year exercise intervention. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(11):2972–2985. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Hoffman BM, Strauman TA, Welsh-bohmer K, Jeffrey N, Sherwood A. Aerobic exercise and neurocognitive performance: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2011;72(3):239–252. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d14633.Aerobic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(2):125–130. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12661673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guiney H, Machado L. Benefits of regular aerobic exercise for executive functioning in healthy populations. Psychon Bull Rev. 2013;20(1):73–86. doi: 10.3758/s13423-012-0345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin LM, Keyser RE, Dsurney J, Chan L. Improved cognitive performance following aerobic exercise training in people with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(4):754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grealy MA, Johnson DA, Rushton SK. Improving cognitive function after brain injury: the use of exercise and virtual reality. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(6):661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassett LM, Moseley AM, Whiteside B, Barry S, Jones T. Circuit class therapy can provide a fitness training stimulus for adults with severe traumatic brain injury: A randomised trial within an observational study. J Physiother. 2012;58(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin LM, Chan L, Woolstenhulme JG, Christensen EJ, Shenouda CN, Keyser RE. Improved Cardiorespiratory Fitness With Aerobic Exercise Training in Individuals With Traumatic Brain Injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;30(6):382–390. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris T, Gomes Osman J, Tormos Muñoz JM, Costa Miserachs D, Pascual Leone A. The role of physical exercise in cognitive recovery after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2016;34(6):977–988. doi: 10.3233/RNN-160687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kushwaha VP, Garland DG. Extremity fractures in the patient with a traumatic brain injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(5):298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basford JR, Chou L-S, Kaufman KR, Brey RH, Walker A, Malec JF, Moessner AM, Brown AW. An assessment of gait and balance deficits after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(3):343–349. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falchook AD, Porges EC, Nadeau SE, Leon SA, Williamson JB, Heilman KM. Cognitive-motor dysfunction after severe traumatic brain injury: A cerebral interhemispheric disconnection syndrome. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2015;37(10):1062–1073. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2015.1077930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman KB, Goldberg M, Bell KR. Traumatic brain injury and pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17(2):473–490, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pattuwage L, Olver J, Martin C, Lai F, Piccenna L, Gruen R, Bragge P. Management of Spasticity in Moderate and Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Head Trauma Rehabil. April 2016. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiou KS, Chiaravalloti ND, Wylie GR, DeLuca J, Genova HM. Awareness of Subjective Fatigue After Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;31(3):E60–68. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wade DT. Outcome measures for clinical rehabilitation trials: impairment, function, quality of life, or value? Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82(10 Suppl):S26–31. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000086996.89383.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallock H, Collins D, Lampit A, Deol K, Fleming J, Valenzuela M. Cognitive Training for Post-Acute Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogdanova Y, Yee MK, Ho VT, Cicerone KD. Computerized Cognitive Rehabilitation of Attention and Executive Function in Acquired Brain Injury: A Systematic Review., Computerized Cognitive Rehabilitation of Attention and Executive Function in Acquired Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. J Head Trauma Rehabil J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;31, 31(6, 6):419, 419–433. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000203, 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solana J, Cáceres C, García-Molina A, Opisso E, Roig T, Tormos JM, Gómez EJ. Improving brain injury cognitive rehabilitation by personalized telerehabilitation services: guttmann neuropersonal trainer. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2015;19(1):124–131. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2014.2354537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shatil E Does combined cognitive training and physical activity training enhance cognitive abilities more than either alone? A four-condition randomized controlled trial among healthy older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:8–8. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cantor JB, Ashman T, Gordon W, Ginsberg A, Engmann C, Egan M, Spielman L, Dijkers M, Flanagan S. Fatigue after traumatic brain injury and its impact on participation and quality of life. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2008;23(1):41–51. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000308720.70288.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starkstein SE, Pahissa J. Apathy following traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(1):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley D, CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teasdale G, Jennett B. ASSESSMENT OF COMA AND IMPAIRED CONSCIOUSNESS: A Practical Scale. The Lancet. 1974;304(7872):81–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hagen C Malkmus D. Durham E. Reha bilitation of the Head Injured Adult: Comprehensive Physical Management Professional Staff of Rancho Los Amigos Hospital; Downey, CA: Levels Cogn Funct; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferguson B ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription 9th Ed. 2014. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014;58(3):328 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4139760/. Accessed September 28, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solana J, Cáceres C, García-Molina A, Chausa P, Opisso E, Roig-Rovira T, Menasalvas E, Tormos-Muñoz JM, Gómez EJ. Intelligent Therapy Assistant (ITA) for cognitive rehabilitation in patients with acquired brain injury. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:58. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-14-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed JC, Reed HBC. The Halstead—Reitan Neuropsychological Battery In: Goldstein G, Incagnoli TM, eds. Contemporary Approaches to Neuropsychological Assessment. Critical Issues in Neuropsychology. Springer US; 1997:93–129. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-9820-3_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan JJ, Lopez SJ. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III In: Dorfman WI, Hersen M, eds. Understanding Psychological Assessment. Perspectives on Individual Differences. Springer US; 2001:19–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1185-4_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Callahan CD, Johnstone B. The clinical utility of the Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test in medical rehabilitation. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 1994;1(3):261–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01989627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Machado TH, Fichman HC, Santos EL, Carvalho VA, Fialho PP, Koenig AM, Fernandes CS, Lourenço RA, Paradela EM de P, Caramelli P, Machado TH, Fichman HC, Santos EL, Carvalho VA, Fialho PP, Koenig AM, Fernandes CS, Lourenço RA, Paradela EM de P, Caramelli P. Normative data for healthy elderly on the phonemic verbal fluency task - FAS. Dement Amp Neuropsychol. 2009;3(1):55–60. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642009DN30100011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lidia Artiola I Fortuny, David Hermosillo Romo, Robert K. Heaton, Roy E. Pardee III: Manual De Normas Y Procedimientos Para La Bateria Neuropsicologia. https://www.amazon.es/Manual-Normas-Procedimientos-Bateria-Neuropsicologia/dp/0970208006. Accessed November 27, 2017.

- 39.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borg G Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2013;32(2):207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chervinsky AB, Ommaya AK, deJonge M, Spector J, Schwab K, Salazar AM. Motivation for Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation Questionnaire (MOT-Q): Reliability, Factor Analysis, and Relationship to MMPI-2 Variables. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1998;13(5):433–446. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(97)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boosman H, Heugten CM, Winkens I, Smeets SM, Visser-Meily JM. Further validation of the Motivation for Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation Questionnaire (MOT-Q) in patients with acquired brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2016;26(1):87–102. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2014.1001409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Devine JM, Wong B, Gervino E, Pascual-Leone A, Alexander MP. Independent, Community-Based Aerobic Exercise Training for People With Moderate-to-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(8):1392–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinstein AA, Chin LMK, Collins J, Goel D, Keyser RE, Chan L. Effect of Aerobic Exercise Training on Mood in People With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Pilot Study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017;32(3):E49–E56. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Driver S, Ede A. Impact of physical activity on mood after TBI. Brain Inj. 2009;23(3):203–212. doi: 10.1080/02699050802695574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leong BK, Mazlan M, Rahim RBA, Ganesan D. Concomitant injuries and its influence on functional outcome after traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(18):1546–1551. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.748832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamilton M, Williams G, Bryant A, Clark R, Spelman T. Which factors influence the activity levels of individuals with traumatic brain injury when they are first discharged home from hospital? Brain Inj. 2015;29(13–14):1572–1580. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2015.1075145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krumpolec P, Vallova S, Slobodova L, Tirpakova V, Vajda M, Schon M, Klepochova R, Janakova Z, Straka I, Sutovsky S, Turcani P, Cvecka J, Valkovic L, Tsai C-L, Krssak M, Valkovic P, Sedliak M, Ukropcova B, Ukropec J. Aerobic-Strength Exercise Improves Metabolism and Clinical State in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Front Neurol. 2017;8. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mossberg K a, Ayala D, Baker T, Heard J, Masel B. Aerobic capacity after traumatic brain injury: comparison with a nondisabled cohort. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(3):315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhambhani Y, Rowland G, Farag M. Reliability of peak cardiorespiratory responses in patients with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(11):1629–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunter M, Tomberlin J, Kirkikis C, Kuna ST. Progressive exercise testing in closed head-injured subjects: comparison of exercise apparatus in assessment of a physical conditioning program. Phys Ther. 1990;70(6):363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dawes HN, Barker KL, Cockburn J, Roach N, Scott O, Wade D. Borg’s Rating of Perceived Exertion Scales: Do the Verbal Anchors Mean the Same for Different Clinical Groups? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(5):912–916. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.CDC. Perceived Exertion (Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale) | Physical Activity | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/measuring/exertion.htm. Accessed January 17, 2018.

- 55.Levinger I, Bronks R, Cody DV, Linton I, Davie A. P erceived Exertion As an Exercise Intensity Indicator in Chronic Heart Failure Patients on Beta-Blockers. J Sports Sci Med. 2004;3(YISI 1):23–27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3990937/. Accessed January 17, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yousefi R, Nourani M, Panahi I. Adaptive cancellation of motion artifact in wearable biosensors. Proc Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc EMBS. 2012:2004–2008. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SDC 1: Video Abstract