Abstract

Sepsis is associated with thrombocytopenia and microvascular thrombosis. Studies have described platelets implication in this pathology but their kinetics of activation and behavior remain poorly known. We show in a mouse model of peritonitis, the appearance of platelet-rich thrombi in organ microvessels and organ damage. Complementary methods are necessary to characterize platelet activation during sepsis as circulating soluble markers and platelet-monocyte aggregates revealed early platelet activation, while surface activation markers were detected at later stage. A microfluidic based ex-vivo thrombosis assay demonstrated that platelets from septic mice have a prothrombotic behavior at shear rate encountered in microvessels. Interestingly, we found that even though phosphoinositide-3-kinase β−deficient platelet mice formed less thrombi in liver microcirculation, peritoneal sepsis activates a platelet alternative pathway to compensate the otherwise mandatory role of this lipid-kinase to form stable thrombi at high shear rate. Platelets are rapidly activated during sepsis. Thrombocytopenia can be attributed in part to platelet-rich thrombi formation in capillaries and platelet-leukocytes interactions. Platelets from septic mice have a prothrombotic phenotype at a shear rate encountered in arterioles. Further studies are necessary to unravel molecular mechanisms leading to this prothrombotic state of platelets in order to guide the development of future treatments of polymicrobial sepsis.

Introduction

Sepsis is a major cause of mortality and critical illness in the world1,2 and is considered as a major public health concern whose incidence is increasing3. Severe sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection4.

It is now well documented that the role of platelets includes an immune response function during the host response to infections5,6. Platelets are thought to play a major role in sepsis with thrombocytopenia being recognized as an independent risk factor for mortality of patients admitted to the intensive care units with severe sepsis or septic shock7. Platelets are anucleated circulating cells playing an essential role in hemostasis and thrombosis. They are highly reactive to extracellular stimuli through activation of a variety of specific membrane receptors for soluble agonists or adhesive proteins allowing platelet adhesion, activation, secretion and aggregation to form a plug, which, together with activation of the coagulation system, safeguards vessel integrity and prevent hemorrhage8. Under conditions of high shear, the initial recruitment of platelets to an injured vessel wall is mediated by the reversible interaction with von Willebrand factor (VWF) that binds to collagen fibers of the subendothelial matrix and the platelet receptor glycoprotein GPIb. This interaction allows platelets to establish contacts with collagen leading to their activation and the release of secondary mediators such as adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and thromboxane A2 (TxA2). These mediators, together with thrombin generated by the coagulation cascade, further activate platelets leading to their aggregation and the stabilization of the platelet-rich thrombus9. Sepsis is a multistep disease in which platelets are implicated through several mechanisms including recruitment of immune cells. This recruitment contributes to a hyper-inflammatory state10 with subsequent development of microvascular occlusive syndromes and thus worsening multiple organ failure11,12. The procoagulant state in sepsis and formation of neutrophils extracellular DNA traps (NETs) and microthrombi as a defense strategy increase the risk of vaso-occlusive complications13. It is important to note that at certain stages of sepsis platelets have a protective role through tempering macrophage-dependent inflammation14 and limiting clinical severity through the podoplanin-CLEC2 axis15.

Several reports suggest that platelets may be a relevant therapeutic target in sepsis. In vitro studies have described bacterial-induced platelet activation processes and identified different mechanisms of interactions between platelets and bacteria16–19. Evidence is accumulating that inhibition of platelet function can modulate inflammatory markers20. Drugs inhibiting platelet activation, such as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) or P2Y12 inhibitors, may have a benefit in reducing thrombo-inflammation, arterial microthrombi and in turn multiple organ failure in critically ill septic patients. Furthermore, new targets for antithrombotic therapy have been proposed such as Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) β isoform that participates in the regulation of a range of functional platelet responses, including sustained activation of αIIbβ3 integrin. It has been shown that in vivo, isoform-selective PI3Kβ inhibitors prevent occlusive thrombus formation but do not prolong the bleeding time21,22. Such inhibitor could be of interest in the treatment of septic patients. However, it is essential to get further insights on the time course of platelet activation during sepsis, on the consequences of sepsis on platelet prothrombotic properties at arterial shear rate and to evaluate the impact of platelet PI3Kβ inhibition. Only a few studies have investigated platelet activation during sepsis in humans13,23–26 or in experimental animal models27,28. Recently, a study of platelet activation dynamics during the progression of a streptococcus pyogenes infection has proposed that monitoring platelet activation may provide prognostic information in this type of sepsis29.

The aim of the present work was to characterize platelet activation during the development of a cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model of polymicrobial peritoneal sepsis in mice. Furthermore, we studied platelet prothrombotic properties at high shear rate encountered in microvessels and evaluated the impact of platelet PI3Kβ inhibition.

Results

Characterization of sepsis and platelet parameters over time in the CLP mice model

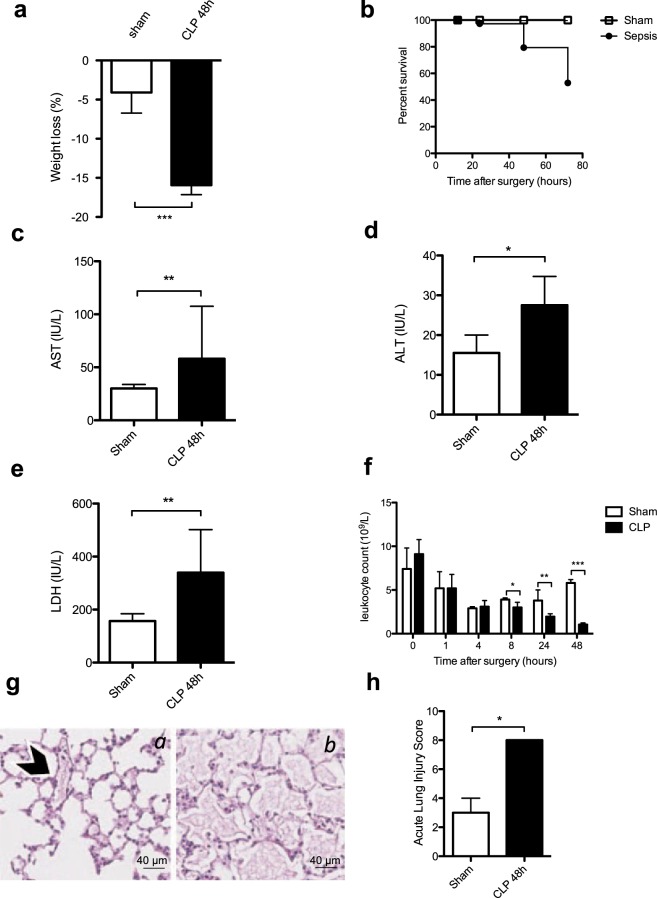

To analyze sepsis development and progression in our mouse model of peritonitis a series of biological parameters were measured at different time points after CLP (Fig. 1). There was significant weight loss in the CLP group (sham −4.1 [−6.7–3.0] % versus CLP −15.9 [−17.2–−11.9] %) accompanied by an overall mortality of 47% three days after surgery (Fig. 1a,b). The plasma levels of IL-1β, TNFα and IL-6 were significantly increased in the CLP group after 6 hours (Suppl Fig. 1) indicating a pro-inflammatory stage rapidly generated following CLP. A marked elevation of liver transaminases AST and ALT was measured in the CLP group (sham AST 30.0 [25.8–33.8] IU/L versus CLP AST 58.0 [48.5–107.5] IU/L, n = 6, p = 0.005 and sham ALT 15.5 [10–20] IU/L versus CLP ALT 27.5 [20.3–34.8] IU/L, n = 6, p = 0.019) indicating liver cytolysis (Fig. 1c,d). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was also significantly increased in the CLP group (Fig. 1e). There was no difference in serum creatinine level measured between the 2 groups (Suppl Fig. 1d). Analysis of these selected biochemical parameters indicated organ cytolysis 48 hours after CLP.

Figure 1.

Characterization of sepsis after cecal ligation and puncture. (a) Weight loss was increased 48 hours post procedure in the CLP group of mice (black bar) compared to the sham group (white bar). Results are expressed as percentage of weight loss and are median [25–75th percentiles] (n = 14, ***p < 0.001). (b) Survival was quantified at 72 hours post CLP. At 72 h, the overall mortality was 47% in CLP group. Results are expressed as percentage of survival (n = 36, p < 0.05). Biochemical analysis were performed with a PENTRA 400 ABXc analyzer for aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (c), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (d) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (e). Results are presented as median [25–75th percentiles] (n = 6, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (f) Leukocyte count was measured 48 h post surgery and compared in sham versus CLP group. Results are expressed as median [25–75th percentiles] (n = 6 to 30 *p < 0.05,**p > 0.001, ***p < 0.0001). (g) Representative images of lung sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin 48 h post surgery. The arrowhead shows a blood vessel section which integrity is conserved in a sham-operated mouse (a). In the CLP group of mice (b) important alveolar injuries are observed as quantified by the Acute Lung Injury (ALI) Score 48 h post CLP induction (h). Results are median ± IQR of 7 independent experiments (*p < 0.05) and representative images are shown (g).

There was a significant leukocyte count decrease in the CLP group after 8 hours that persisted until 48 hours of sepsis (5.8 [4.7–6.2] 109/L in sham group versus 1.05 [0.8–1.23] 109/L in CLP group, (n = 30), p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1f). Lymphocyte and monocyte counts were particularly low 48 hours after the surgery while neutrophil count declined significantly 4 hours after CLP (Suppl Fig. 2a–c).

Histological assessment of lung sections revealed significant inflammatory infiltrates as demonstrated by interalveolar thickening, interstitial edema and a significantly elevated mean acute lung injury score 48 hours after CLP (Fig. 1g,h). Neutrophil infiltration in both lung and liver was increased in the CLP group (Suppl Fig. 3a).

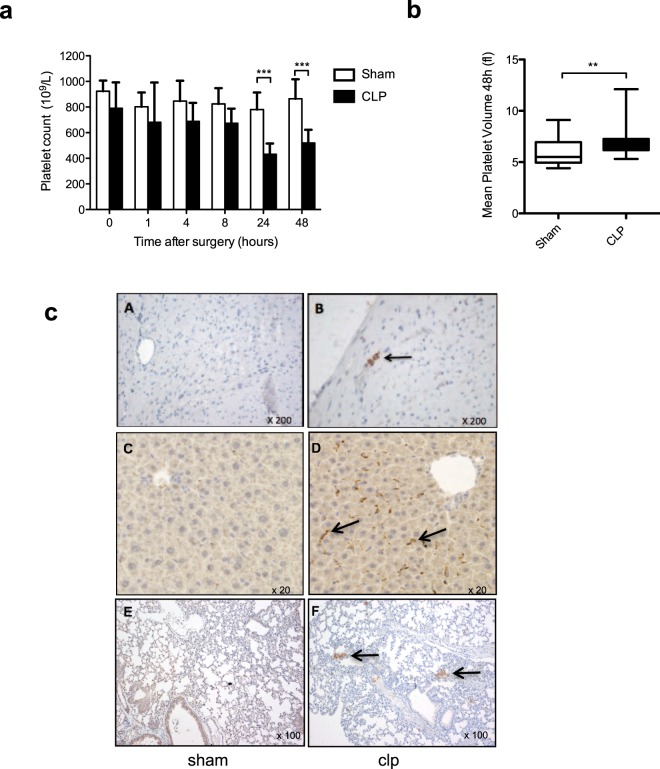

As shown in Fig. 2A, we observed a progressive platelet count decrease in the CLP group that became significant after 24 hours (sham 780 [657–913] 109/L versus CLP 431 [380–515] 109/L, n = 15, p < 0.0001) and persisted two days post CLP (sham 864 [785–1016] 109/L versus CLP 519 [393–622] 109/L, n = 30, p < 0.0001). A significant increase in mean platelet volume was also observed at 48 hours suggesting occurrence of platelet renewal (sham 5.5 [5.0–7.0] fl versus CLP 6.9 [6.2–7.3] fl, n = 30, p = 0.001) (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, the circulating platelet count decrease in the CLP group correlated with the appearance of platelet-rich thrombi in tissue microvessels as shown by immunohistopathology (Fig. 2c). Thrombi could be observed in the heart (upper panels), in periportal capillaries (middle panels), and in pulmonary microvessels (lower panels) of the CLP group of mice while no thrombus formation could be seen in the sham group (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Sepsis promotes thrombocytopenia and thrombus formation in lung capillaries after cecal ligation and puncture. (a) Whole blood platelet count kinetics at 48 h post CLP surgery. Results are expressed as platelets x 109/L and are median ± IQR of 30 independent experiments (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (b) Comparison of Mean Platelet Volume (MPV) 48 h post CLP surgery. Whisker boxes are constructed as follow: min, max, median, 25–75th percentiles (n = 30, **p < 0.01). (c) Representative histological sections of heart (A,B), liver (C,D) and lung (E,F) tissues 48 h post surgery. Sections from CLP (B,D,F) or sham-operated animals (A,C,E) as controls were stained with Masson’s trichrome and platelets were specifically labeled with an anti-αIIb antibody. Arrows highlight platelet-rich thrombi in microvessels. Images (x20, x100 and x200 magnification) shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Of note, identification of bacteria from blood cultures obtained 48 hours after CLP indicated the presence of enterococcus faecalis, and of citrobacter braakii (Suppl Fig. 3b).

Kinetics of platelet activation during sepsis

To investigate the level and kinetics of platelet activation during sepsis we analyzed platelet intrinsic markers including membrane exposure of CD62P and fluorescently labeled fibrinogen binding to activated GpIIbIIIa (αIIbβ3), formation of heterotypic aggregates between platelets and leukocytes and soluble markers in plasma such as soluble CD40L (sCD40L) and eicosanoids.

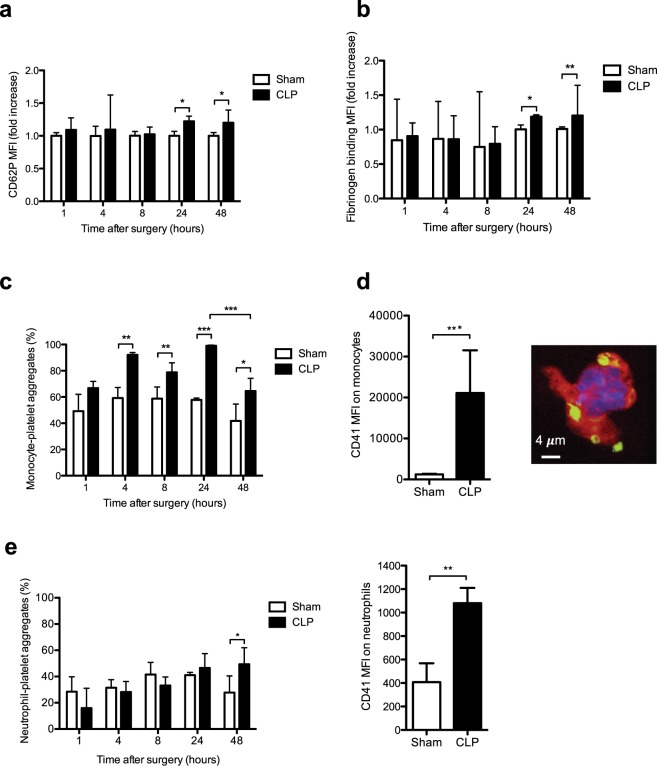

P-selectin (CD62P) exposure at the platelet surface assessed by flow cytometry at intervals following CLP indicated a significant platelet activation 24 hours after CLP that persisted at 48 hours (Fig. 3a). Consistent with these results, fibrinogen fixation on activated GpIIbIIIa was significantly enhanced 24 hours after CLP and further increased at 48 hours (Fig. 3b). However, activated platelets may be rapidly removed from the circulation and/or conjugated to leukocytes30. As shown in Fig. 3c, as soon as 4 hours monocyte-platelet interactions significantly increased with a maximal increase 24 hours after surgery. In spite of an important decline of circulating monocytes (Suppl Fig. 2b), platelet-monocyte aggregates were still significantly elevated 48 hours after CPL. Figure 3d is a representative confocal image showing that several platelets interacted with monocytes 24 hours after CLP. Interestingly, at that time point, the density of platelets per monocyte, estimated by median fluorescence intensity of the platelet marker CD4131, was strongly increased following sepsis compared to Sham operated mice (Fig. 3d). Of note, the formation kinetics of neutrophil-platelet aggregates formation were different. Indeed, these heterotypic aggregates were observed later in the sepsis and were significantly increased 2 days after surgery with an increase in the density of platelets per neutrophil compared to Sham mice (Fig. 3e, right panel).

Figure 3.

Expression of surface platelet activation markers and elevation of leukocyte-platelets interactions during sepsis. (a) Expression of the surface platelet activation marker CD62P analyzed by flow cytometry during sepsis. (b) Activation of αIIbβ3 (GpIIbIIIa) integrin at the platelet surface assessed by oregon green fibrinogen binding and flow cytometry analysis. Results are expressed as median fluorescence intensity and are median fold increase ± IQR of 6 to 8 independent experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). (c) Whole blood monocyte-platelet aggregates quantified at different times post surgery in sham and CLP-operated mice. Results are expressed as percentage of monocyte-platelet aggregates and are median ± IQR of 4 to 6 independent experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (d) Density of platelets per monocytes. The MFI values of the platelet marker (CD41) on monocytes was measured 24 h after CLP by flow cytometry to evaluate the platelet density per monocyte (left panel). After sorting by flow cytometry the platelet-monocyte aggregates were spin down onto poly-lysine coated slides and observed by confocal microscopy (right panel). A representative confocal image is show to illustrate the interaction of platelets (CD41, green) and monocyte (CD115, red) 24 h post CLP. The monocyte nucleus was labeled with DAPI (blue). (e) Whole blood neutrophil-platelet aggregates quantified at different times after surgery in sham and CLP-operated mice. Results are expressed as percentage of neutrophil-platelet aggregates and are median ± IQR of 3 to 7 independent experiments (*p < 0.05) (left panel). The MFI values of the platelet marker (CD41) on neutrophils was measured 48 h after CLP to evaluate the platelet density per neutrophil (right panel).

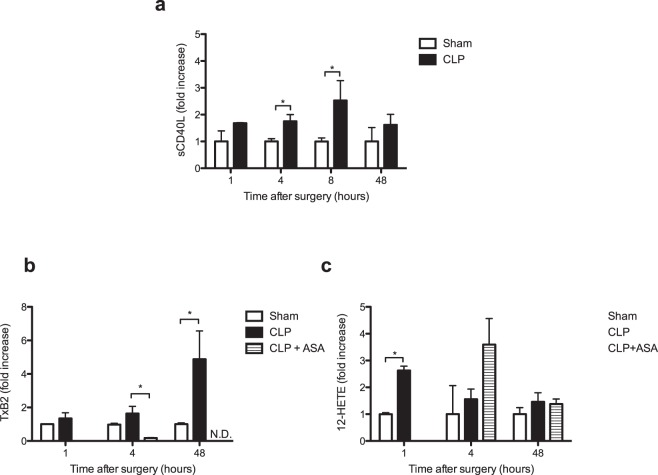

Analysis of soluble markers of platelet activation, such as plasmatic sCD40L and eicosanoids, provides the opportunity to detect low grade circulating platelet activation or platelet activation even if activated platelets are no longer circulating (i.e. bound to the endothelium) or in complex with leukocytes32. CLP significantly increased plasma levels of sCD40L as soon as 4 hours (1.75 [1.48–1.99] fold increase n = 3, p = 0.04) and 8 hours (2.53 [1.66–3.27] fold increase, n = 4, p = 0.006) after surgery (Fig. 4a). This increase was no longer significant 2 days after CLP.

Figure 4.

Early elevation of soluble markers of platelet activation during sepsis. (a) Levels of plasma soluble CD40L (sCD40L) and eicosanoids at different times in sham and CLP mice. Results are expressed as fold increase and are median (25–75th percentile) of 4 to 7 independent experiments (*p < 0.05). (b) Kinetics of TxB2, the stable metabolite of TxA2, and (c) 12-HETE production in plasma of sham, CLP-operated mice and CLP-operated mice treated with aspirin. The quantification was performed by a lipidomics LC-MS/MS technique. Results are expressed as fold increase and are median (25–75th percentile) of 3 to 6 independent experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). N.D., not detectable.

Eicosanoids are locally acting bioactive signalling lipids derived from arachidonic acid and related polyunsaturated fatty acids that regulate a diverse set of homeostatic and inflammatory processes33. After activation, platelets produce eicosanoids via cyclooxygenase and lipooxygenase pathways, particularly thromboxane A2 (TxA2) and 12-hydroeicosatetraeinoic acid (12-HETE). Thromboxane B2 (TxB2), the stable metabolite of TxA2, increased 4 hours after CLP to become significantly more abundant after 48 hours in the CLP group (Fig. 4b). As a control, inhibition of cyclooxygenase by aspirin treatment of mice fully inhibited TxB2 production following CLP. The lipoxygenase product 12-HETE was also rapidly produced, measured 1 hour after CLP its plasma concentration was significantly elevated compared to the sham group of mice (Fig. 4c). In this case, as expected, inhibition of cyclooxygenase by aspirin did not affect the production of this lipoxygenase product (Fig. 4c).

Overall, these data show that there is early platelet activation in sepsis which can be detected by quantification of monocyte-platelets aggregates in whole blood and soluble markers in plasma (sCD40L and eicosanoids).

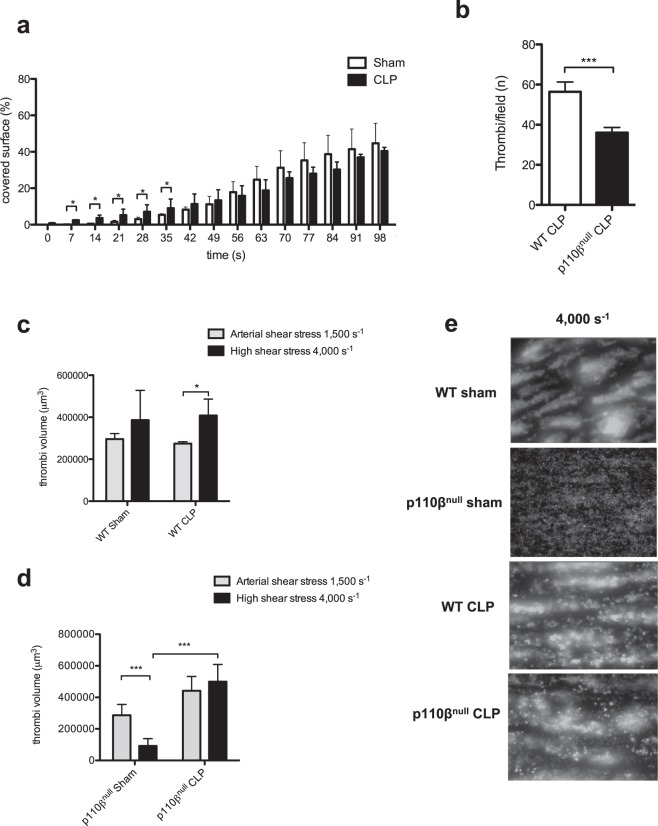

Sepsis induces a prothrombotic platelet state under flow and brings out an alternative mechanism enabling platelets to form stable thrombus at high shear rate in the absence of PI3Kβ

To further investigate the effect of sepsis on platelets we studied thrombus formation under flow conditions encountered in microcirculation. Interestingly, despite a decreased platelet count at 48 hours, the CLP group exhibited a significantly faster adhesion and formation of platelet thrombus compared to the sham group of mice. However, after forty seconds of flow, the surface coverage was not significantly different in the two groups (Fig. 5a). Sepsis thus induced a pre-activation stage of platelets allowing them to very rapidly interact with the collagen surface at a shear rate of 1500 s−1 to form a growing thrombus.

Figure 5.

Platelet pro-thrombotic properties at arterial flow and bypass of PI3Kβ for thrombus stability at high shear rate during sepsis. (a) DIOC6-labeled platelets in whole blood from the CLP (black bar) or sham (white bar) mice 48 h post intervention were perfused through a collagen-coated microcapillary at a physiological arterial rate of 1500 s−1. Surface coverage (%) by fluorescent platelets was analyzed using ImageJ software. Results shown are median ± IQR of 4 independent experiments (*p < 0.05). (b) Platelet-rich thrombi formed in the liver 48 h post CLP were detected as in Fig. 2 (C-D) and quantified. 5 mice from each group and 5 to 10 field per mice were analyzed. Results are expressed as median ± IQR (***p < 0.001). (c–e) DIOC6-labeled platelets in whole blood from platelet PI3Kβ-deficient mice (p110βnull) or wild type mice (WT) were perfused through a collagen-coated microcapillary at a physiological arterial shear rate of 1500 s−1, followed by a high shear rate of 4000 s−1. Thrombi volumes (μm3) were analyzed using ImageJ software. Results are expressed as median ± IQR of 4 to 6 independent experiments (***p < 0.001). (e) Representative images showing the platelet thrombi remaining after 1 min of high shear rate (4000 s−1).

Class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase β (PI3Kβ) is known to play an important role in platelet activation and has been proposed as a potential antithrombotic target21,22,34. To evaluate its role during sepsis we took advantage of our mouse model presenting an invalidation of the catalytic subunit of PI3Kβ (p110β) specifically in platelets35. As shown in Fig. 5b, following CLP, the number of thrombi in periportal zone of the liver was significantly decreased in the absence of PI3Kβ in platelets. However, this decrease had no effect on weight loss or the mean acute lung injury score 48 hours after CLP (Suppl Fig. 4). Deficiency of PI3Kβ in platelets is known to induce an instability in arterial thrombus at high shear rate35. Therefore, we performed CLP in wild type and p110β-deficient platelet mice and analyzed their capacity to form stable thrombi at high shear rate ex-vivo. Blood from both groups of mice was first perfused on collagen at 1500 s−1 for 150 seconds to form comparable thrombi and then an acceleration of the blood flow was generated to reach a high shear rate of 4000 s−1. In the wild type sham or CLP groups the thrombi formed at 1500 s−1 were stable and continued to grow at 4000 s−1 (Fig. 5c–e). As expected, in the absence of p110β, platelet thrombi rapidly destabilized at high shear rate, leaving a single platelet layer on the collagen surface with some small aggregates (Fig. 5d,e). Strikingly, septic conditions reversed the thrombus instability at high shear rate in p110β-deficient platelet mice. Indeed, following CLP, platelet thrombi were stable at 4000 s−1 indicating that sepsis allowed platelets to overcome the defect of thrombus stability induced by PI3Kβ invalidation at high shear rate (Fig. 5d,e).

Discussion

Sepsis is a complex disease which can rapidly evolve to septic shock and subsequent organ failure in the absence of required early and aggressive management generally needed to stop the progression to septic shock and subsequent organ failure. Platelets are probably among the first responding cells during sepsis development and their roles and influences are likely different during sepsis progression. They can have protective roles by tempering macrophage-dependent inflammation, regulatory functions by maintaining inflammation or negative roles by precipitating microvessels dysfunction and in turn multiple organ failure. Here we analyzed the kinetics and characteristics of platelet activation and their behavior during sepsis in a mouse model of peritoneal sepsis36. CLP in rodents has become the most widely used model for experimental sepsis and considered a standard in sepsis research37. The survival rates found in our study, the severity of sepsis and multiple organ failure were comparable to those reported in the literature36–38. Lung histology revealed inflammatory acute lung injury as also reported in experimental polymicrobial peritonitis36. Thrombocytopenia was present significantly one day after CLP and persisted at 48 hours. Thrombocytopenia is common in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients and a decline in platelet count, even without thrombocytopenia, adds significant prognostic information to the current parameters used in the current ICU scoring system39,40. Several studies have reported that failure of the platelet count recovery to normal level during critical illness is associated with a higher mortality41,42.

The causes of thrombocytopenia in sepsis are still unclear but platelet consumption following activation and aggregation or adhesion to the endothelium and/or leukocytes likely contribute. Indeed, 48 hours after CLP we observed platelet-rich thrombi in the microcirculation of different organs including liver, kidney and lung. This appearance of platelet-rich thrombi correlated with organ failure and likely contributed to ischemic complications.

To study the kinetics of platelet activation during sepsis we analyzed different parameters including intrinsic and soluble platelet markers as well as formation of heterotypic platelet leukocytes aggregates. CD62P (P-selectin) was significantly increased at 24 hours post onset of sepsis. Consistent with this a significant increase in αIIbβ3 activation assessed by fibrinogen binding on the platelet surface was observed 24 hours after CLP and persisted at 48 hours. In septic patients, Gawaz et al.24 also observed increased αIIbβ3 activation on the platelet surface compared to controls. However, since activated platelets may rapidly be eliminated from circulation, measurement of intrinsic circulating platelet activation markers may not be sensitive enough to detect platelet activation, particularly in the first hours of sepsis24. Indeed, in patients with septic shock it has been suggested that the most active cells with high adhesion potential might be sequestered from circulation and thus escape detection30,43. In this context, we quantified soluble platelet markers and analyzed circulating heterotypic aggregates between platelets and leukocytes as valuable indicators of platelet activation during sepsis.

The formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates is now recognized as a sensitive marker of in vivo platelet activation and is a feature of inflammatory conditions30,44,45. These aggregates are mediated via multiple ligands and receptors including P-selectin which is translocated to the surface of activated platelets44. We found an increase in monocyte-platelet aggregates formation, as early as 4 hours after CLP that persisted until 48 hours despite a drop in circulating monocyte count. The density of platelet per monocyte was also strongly increased. In contrast, the level of circulating neutrophil-platelet aggregates showed no significant differences until the first 24 hours but significantly increased 48 hours after CLP. An increase of platelet-leukocyte adhesion has been reported in patients with sepsis, and these heterotypic interactions were shown to decrease when patients developed multiple organ failure24. The exact mechanisms, regulations and clinical significance of such platelet-leukocyte interaction in sepsis are still poorly understood46. In our sepsis model the rapid increase in platelet-monocyte aggregates suggests early activation of a set of platelets in circulation. Consistent with this, the plasma level of sCD40L significantly increased 4 hours after CLP. These levels remained significantly high 8 hours after CLP but decreased 48 hours later. CD40L shedding from platelets following CLP has been shown to involve the matrix metalloprotease-947. sCD40L contributes to the regulation of neutrophil recruitment and lung damage in sepsis. Higher sCD40L levels were found in 49 patients with meningococcal sepsis and 15 patients with African tick bite fever compared to controls48,49. In septic patients, a multicenter prospective study has shown that circulating sCD40L levels were significantly higher in septic patients than in controls, and in non-survivors compared to survivors50.

Activated platelets are known to generate several bioactive lipids including eicosanoids acting as regulators of a diverse set of homeostatic and inflammatory processes33. We found that circulating levels of the cyclo-oxygenase product TxB2 (the stable metabolite of TxA2) were significantly elevated in the early phase of sepsis and remained high 48 hours after CLP. As expected, treatment of mice with the cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor aspirin abolished this production. The lipo-oxygenase product 12-HETE was also significantly elevated 1 hour after CLP and was not affected by aspirin treatment. Overall, these data show that CLP-mediated experimental peritonitis in mice promotes a rapid activation of platelets detectable after 1 to 4 hours by measuring circulating soluble markers of platelet activation and monocyte-platelet aggregates. Activation markers at the surface of circulating platelets such as P-selectin expression and αIIbβ3 activation are only significantly detectable 24 to 48 hours after CLP, when thrombocytopenia is already well established. Therefore, these results show that it is important to investigate both soluble and intrinsic platelet markers of activation to determinate the onset of platelet activation during sepsis.

Besides markers of platelet activation, another important question concerns the prothrombotic feature of platelets during sepsis, particularly at a shear rate encountered in microvessels. The dynamics of platelet thrombus formation and stabilization under flow is yet poorly studied in septic conditions. Using videomicroscopy analysis we observed that septic conditions significantly accelerated platelet adhesion and thrombus growth at a shear rate found in microvessels. Of note, this was observed with blood from mice 48 hours after CLP, a stage where a significant thrombocytopenia is present. This data reveals a prothrombotic behavior of platelets at arterial flow conditions during sepsis. Importantly, the thrombus formed were stable, even at very high shear rates. We and others have previously shown that PI3Kβ is mandatory for platelet activation and thrombus stability in both human and mouse models at high shear rate. PI3Kβ inhibitors have thus been proposed as potential antithrombotic drugs21. Therefore, we checked whether such inhibitors could be relevant to treat septic patients to prevent ischemic events arising from thrombosis in microcirculation, where the shear rate is elevated. Using p110β-null platelet mice, we found that absence of PI3Kβ significantly decreased the number of thrombi formed in the liver following CLP but was not sufficient to impair weight loss and lung injury. This decreased number of thrombi suggests that PI3Kβ contributed to the processes of platelet activation during sepsis. However, once formed these thrombi appeared stable at high shear rate even in the absence of PI3Kβ. In fact, sepsis restored the ability of platelets to form a stable thrombus at high shear rate in the absence of platelet PI3Kβ, indicating that septic conditions allow platelets to compensate for PI3Kβ deficiency. Thus, despite a decrease in the number of thrombi formed in the periportal zone of the liver, our results suggest that PI3Kβ inhibitors may not be sufficient to efficiently treat septic patients. How sepsis can modify platelets to allow them to form a stable thrombus at high shear rate in the absence of PI3Kβ remains to be established. It is noteworthy that the GpIb-VWF axis is exacerbated and important in sepsis51–53 and may contribute to compensate the lack of PI3Kβ in thrombus stabilization at high shear rates.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that platelets are rapidly activated in the CLP model of peritonitis and that soluble and surface expression markers as well as monocyte-platelet aggregates should be quantified to determine platelet activation during sepsis. Thrombocytopenia can be attributed in part to platelet-rich thrombi formation in capillaries and platelet-leukocytes interactions. Platelets from septic mice have a prothrombotic phenotype at a shear rate encountered in arterioles. We propose that sepsis activates an alternative mechanism enabling platelets to bypass the normally mandatory role of PI3Kβ to form stable thrombus at high shear rates. Further studies are now necessary to unravel the molecular mechanisms leading to this prothrombotic state of platelets at high shear rate as this may unravel new risk markers and guide the development of future treatments of polymicrobial sepsis.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of the Midi-Pyrénées Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation (Comité National de Réflexion Ethique sur l′Expérimentation Animale – Midi-Pyrénées) and with the French Ministry of Agriculture license. This study was approved by the Midi-Pyrénées Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation (N°MP/02/39/05/12, date 2012/10/02).

Male C57BL/6 J mice were obtained from Janvier Labs (Saint-Berthevin, Mayenne, France). PF4-cre/p110βflox/flox mice were generated by crossing a mouse line in which exons 21 and 22 of the kinase domain of p110β are flanked by loxP sites (p110β flox/flox) with transgenic animals expressing the Cre recombinase specifically in megacaryocytes under the control of the PF4 promoter (PF4-Cre/p110wt/wt). PF4-Cre/p110β flox/wt mice were then crossed with p110β flox/flox mice to produce platelet-specific p110β-null mice PF4-Cre/110β flox/flox. They were obtained in a mendelian ratio, and were healthy, with no growth abnormalities. These animals exhibited normal size and platelet count35,54. We used 20-week-old animals, weighing 25–30 g. Mice had access to food and water ad libitum and were not fasted prior to CLP.

Experimental protocol design of sepsis

Polymicrobial sepsis was induced by a CLP procedure as previously described37,38. Briefly, a laparotomy was performed under general anaesthesia, with the cecum ligated at 20% of its total length, below the ileocecal valve, and was punctured once with a 20-gauge needle. The cecum was then returned into the peritoneal cavity. Sham mice underwent the laparotomy without ligation and puncture. When indicated, mice were treated with aspirin (10 µg/g, intraperitoneal injection). Spontaneous mortality was followed four days after the surgery.

Systemic platelet and leukocyte counts

Blood samples were collected by puncture of the lower vena cava utilizing heparinized syringe (0.1 ml heparin (100 IU/ml) for 0.9 ml of blood). Blood cells counts were performed on MICROS-60 analyzer (ABX-Diagnostics, Baden, Switzerland).

Bacteriology

One milliliter of blood from sham and CLP group was cultured in Petri dishes with sheep blood and incubated for 48 hours at 37 °C in an aerobic atmosphere. Bacterial colonies identification was conducted using VITEK® automated system (BioMerieux, USA).

Biochemical diagnostic assays

Serum was obtained after centrifugation (2800 g, 10 min) and immediately frozen and stored at −80 °C. Dosages were performed with PENTRA 400 ABX© (Horiba Medical ®) biochemical analyzer for serum creatinine, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT).

Flow cytometry

In order to analyze surface molecules expression (CD62P and αIIbβ3) on circulating platelets, blood was collected (1:10 acid citrate dextrose (ACD: 3% trisodium citrate 5.5-hydrate, 1.4% citric acid, 2% anhydrous glucose)) at different time after surgery. Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) was incubated (10 min, RT) with an anti-CD62P FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibody (BD PharmigenTM) to analyze CD62P expression. PRP was also incubated with fluorescent fibrinogen (Fibrinogen Oregon green® 488, InvitrogenTM) permitting analysis of the changes in affinity of αIIbβ3 for fibrinogen. Platelet-leukocyte interactions were studied using blood samples (collected in 1:10 ACD), fixed prior to analysis with CELL-FIX© for 20 min and washed in 2 ml PBS. After centrifugation (300 g, 4 min), the pellet was resuspended and incubated with anti-CD41 FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibody (BD PharmingenTM), PE-conjugated anti-Ly-6G Gr-1 monoclonal antibody, PE-conjugated anti-CD115 monoclonal antibody (eBioscience) or with the corresponding isotypes. ACK buffer (0.14 M ammonium chloride, 0.017 M Tris HCl, pH 7.4) was used for red blood cells lysis.

Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry using FACS-VerseTM (BD Biosciences) and the FACS SuiteTM software. The platelet density per monocyte or neutrophil was evaluated by measuring the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the platelet marker (CD41) on monocytes or neutrophils as previously reported by Rutten et al.31.

ELISA

Platelet poor plasma (PPP) was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C before analysis. Soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L) was measured in plasma with mouse sCD40L platinium ELISA kit (Affymetric eBioscienceTM).

Histology

Lungs were excised and formalin-fixed for 24 hours. Then, they were immersed in 70% ethanol solution. Four randomly selected sites from each inflation-fixed lung were embedded in paraffin, and sections were cut for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Lung injury severity was quantified in a blinded manner by adoption of a semi-quantitative scoring system, using the Acute Lung Injury (ALI) score taking into account 4 variables (leukocyte infiltration, fibrin/alveolar edema, alveolar wall thickness, intra-alveolar haemorrhage). The severity of each variable was quantified from 0 to 4 (absence, minimal: 1 to 3 alveoli, light > 3 alveoli, moderate: 2/3 of the surface area, severe: all the alveoli)55. Maximum score was 16. Leukocyte infiltration was studied by immunohistochemistry using the Ly6B.2 antibody (AbD SerotecTM Bio-Rad Compagny).

Plasma eicosanoids measurement by high performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

PPP samples were stored at −80 °C until lipid extraction. LC-MS/MS was performed as detailed elsewhere56 using HPLC grade methanol, methyl formate and acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, lipid preparation from all samples was carried out through solid-phase extraction using hydrophobic polystyrene-divinylbenzene resin in dedicated 96-well plates (Chromabond multi96 HR-X 50 mg; Macherez-Nagel). After complete loading, columns were washed twice with H2O/MeOH (90/10, v/v) and dried under aspiration for 15 min. Samples were dried using nitrogen, dissolved again in methanol (10 μL) and transferred to liquid chromatography before LC-MS/MS analysis.

Flow assays on collagen matrix

Biochips microcapillaries (Vena8Fluro + , Cellix) were coated with a collagen fibril suspension (50 μg/ml) and incubated at 37 °C for one hour prior to being saturated with a solution of 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) without Ca2+/Mg2+. Mouse blood was drawn into heparin (10 IU/mL), and DIOC6 (2 µM) was used to label platelets. Using a syringe pump (Legato 200, KDScientifics) to apply a negative pressure, labeled blood was then perfused through a microcapillary for indicated time at a wall shear rate of 1500 seconds−1, and, when indicated, formed thrombi were then exposed to a high shear rate of 4000 seconds−1 as described35. Platelet adhesion and thrombus formation was visualized with a x40 oil immersion objective for both fluorescent and transmitted light microscopy; light source was provided by Colibri LED System (Zeiss) and was recorded (high resolution CCD cooled camera, Orca-R2, Hamamatsu) in real time (1 frame every 5 seconds). Image sequences of the time-lapse recording and analysis of surface coverage were performed offline on a single frame by quantification of pixel surface after manual thresholding using ImageJ. Thrombi volumes are calculated by thresholding of surface covered by thrombi on slice of Z-stack images and addition of voxel (automatically converted into µm3 by ZenZeiss software).

Statistical analysis

Values are not normally distributed and are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). To compare differences between groups, the Mann-Whitney test was used. Analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0a for Mac). P value < 0.05 was considered significant and n represents the number of animals pooled together from each experiment.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the personnel of Anexplo animal facilities for animal handling (US006/CREFRE Inserm/UPS), the Genotoul Imaging facility (Inserm U1048), the Cytometry facility of Inserm U1048, and the MetaToul-Lipidomic facility of Inserm U1048. We thank Dr Mick Molloy for his kind help in English editing. The authors thank all members from the B.P. laboratory. This work was supported by Inserm, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (grant DEQ. 20170336737) and the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-12-JSV1-0012-01). B.P. is a scholar of the Institut Universitaire de France.

Author Contributions

F.V.B., A.J., V.M., M.-P.G., M.M., C.G., J.S. designed and performed most experiments and analyzed data; H.H.-C., P.S., V.M. and B.P. designed experiments and analyzed data, F.V.B. and B.P. wrote the article.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-31910-8.

References

- 1.Fleischmann C, et al. Assessment of Global Incidence and Mortality of Hospital-treated Sepsis. Current Estimates and Limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:259–272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0781OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent J-L, et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the Intensive Care Over Nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:380–386. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Critical Care Medicine. 2013;41:1167–1174. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenne CN, Kubes P. Platelets in inflammation and infection. Platelets. 2015;26:286–292. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2015.1010441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeaman MR. Platelets: at the nexus of antimicrobial defence. Nat Rev Micro. 2014;12:426–437. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venkata C, Kashyap R, Farmer JC, Afessa B. Thrombocytopenia in adult patients with sepsis: incidence, risk factors, and its association with clinical outcome. Journal of Intensive Care. 2013;1:9. doi: 10.1186/2052-0492-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furie B, Furie BC. Mechanisms of Thrombus Formation. N Engl Med. 2008;359:938–949. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nieswandt B, Varga-szabo D, Elvers M. Integrins in platelet activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:206–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cognasse, F. The inflammatory role of platelets via their TLRs and Siglec receptors. Frontiers in Immunology6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kilic YA, Kilic I, Tez M. Sepsis and multiple organ failure represent a chaotic adaptation to severe stress which must be controlled at nanoscale. Crit Care 2009. 2009;13:424. doi: 10.1186/cc8140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien JM, Ali NA, Abraham E. Year in review 2007: Critical Care – multiple organ failure and sepsis. Crit Care 2009. 2008;12:228. doi: 10.1186/cc6950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald B, et al. Platelets and neutrophil extracellular traps collaborate to promote intravascular coagulation during sepsis in mice. Blood. 2017;129:1357–1367. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-741298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiang B, et al. Platelets protect from septic shock by inhibiting macrophage-dependent inflammation via the cyclooxygenase 1 signalling pathway. Nat Commun. 2013;4:264. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rayes J, et al. The podoplanin-CLEC-2 axis inhibits inflammation in sepsis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:840. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02402-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arman M, et al. Amplification of bacteria-induced platelet activation is triggered by Fc RIIA, integrin IIb 3, and platelet factor 4. Blood. 2014;123:3166–3174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-540526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox D, Kerrigan SW, Watson SP. Platelets and the innate immune system: mechanisms of bacterial-induced platelet activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1097–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moriarty RD, Cox A, McCall M, Smith SGJ, Cox D. Escherichia coliinduces platelet aggregation in an FcγRIIa-dependent manner. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14:797–806. doi: 10.1111/jth.13226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watson CN, et al. Human platelet activation by Escherichia coli: roles for FcγRIIA and integrin αIIbβ3. Platelets. 2016;27:535–540. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2016.1148129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muhlestein JB. Effect of antiplatelet therapy on inflammatory markers in atherothrombotic patients. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:71–82. doi: 10.1160/TH09-03-0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson SP, et al. PI 3-kinase p110β: a new target for antithrombotic therapy. Nat Med. 2005;11:507–514. doi: 10.1038/nm1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nylander S, et al. Human target validation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)β: effects on platelets and insulin sensitivity, using AZD6482 a novel PI3Kβ inhibitor. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:2127–2136. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Layios N, et al. Sepsis prediction in critically ill patients by platelet activation markers on ICU admission: a prospective pilot study. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2017;5:32. doi: 10.1186/s40635-017-0145-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gawaz M, Dickfeld T, Bogner C, Fateh-Moghadam S, Neumann FJ. Platelet function in septic multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:379–385. doi: 10.1007/s001340050344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faraday N, et al. Leukocytes Can Enhance Platelet-mediated Aggregation and Thromboxane Release via Interaction of P-selectin Glycoprotein Ligand 1 with P-selectin. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:145–151. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200101000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzgerald JR, et al. Fibronectin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus mediate activation of human platelets via fibrinogen and fibronectin bridges to integrin GPIIb/IIIa and IgG binding to the FcgammaRIIa receptor. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:212–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tóth J, et al. Characteristics of thrombin generation in a fulminant porcine sepsis model. Thromb Res. 2017;158:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akinosoglou K, et al. Platelet reactivity in sepsis syndrome: results from the PRESS study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:2503–2512. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurley SM, Lutay N, Holmqvist B, Shannon O. The Dynamics of Platelet Activation during the Progression of Streptococcal Sepsis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0163531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zarbock A, Polanowska-Grabowska RK, Ley K. Platelet-neutrophil-interactions: Linking hemostasis and inflammation. Blood Rev. 2007;21:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rutten B, et al. Platelet density per monocyte predicts adverse events in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:353–360. doi: 10.1160/th15-03-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henn V, et al. CD40 ligand on activated platelets triggers an inflammatory reaction of endothelial cells. Nature. 1998;391:591–594. doi: 10.1038/35393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dennis EA, Norris PC. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:511–523. doi: 10.1038/nri3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nylander S, Wågberg F, Andersson M, Skärby T, Gustafsson D. Exploration of efficacy and bleeding with combined phosphoinositide 3-kinase β inhibition and aspirin in man. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:1494–1502. doi: 10.1111/jth.13027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laurent P-A, et al. Platelet PI3K and GSK3 regulate thrombus stability at a high shear rate. Blood. 2015;125:881–888. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-588335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrera G, et al. Model of Polymicrobial Peritonitis That Induces the Proinflammatory and Immunosuppressive Phases of Sepsis. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:1280–1288. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01127-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Flierl MA, Ward PA. Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nature Protocols. 2009;4:31–36. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz S, et al. Sepsis modeling in mice: ligation length is a major severity factor in cecal ligation and puncture. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental. 2016;4:138. doi: 10.1186/s40635-016-0096-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreira FL. Serial Evaluation of the SOFA Score to Predict Outcome in Critically Ill Patients. JAMA. 2001;286:1754. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreau D, et al. Platelet count decline: an early prognostic marker in critically ill patients with prolonged ICU stays. Chest. 2007;131:1735–1741. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akca S, et al. Time course of platelet counts in critically ill patients. Critical Care Med. 2002;30:753–756. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strauss R, et al. Thrombocytopenia in patients in the medical intensive care unit: Bleeding prevalence, transfusion requirements, and outcome. Critical Care Med. 2002;30:1765–1771. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russwurm S, et al. Platelet and Leukocyte Activation Correlate with the Severity of Septic Organ Dysfunction. Shock. 2002;17:263–268. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michelson AD, Barnard MR, Krueger LA, Valeri CR, Furman MI. Circulating Monocyte-Platelet Aggregates Are a More Sensitive Marker of In Vivo Platelet Activation Than Platelet Surface P-Selectin: Studies in Baboons, Human Coronary Intervention, and Human Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2001;104:1533–1537. doi: 10.1161/hc3801.095588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finsterbusch M, Schrottmaier WC, Kral-Pointner JB, Salzmann M, Assinger A. Measuring and interpreting platelet-leukocyte aggregates. Platelets. 2018;88:1–9. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2018.1430358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heffner JE. Platelet-neutrophil interactions in sepsis - platelet guilt by association? Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:366–368. doi: 10.1007/s001340050342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rahman M, et al. Platelet shedding of CD40L is regulated by matrix metalloproteinase-9 in abdominal sepsis. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1385–1398. doi: 10.1111/jth.12273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inwald DP, Peters MJ, Faust SN, Levin M, Klein N. The Role of Platelet CD40L in Inflammation. J Intensive Care Society. 2005;6:28–29. doi: 10.1177/175114370500600117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Damås JK, et al. Increased levels of soluble CD40L in African tick bite fever: possible involvement of TLRs in the pathogenic interaction between Rickettsia africae, endothelial cells, and platelets. Journal Immunol. 2006;177:2699–2706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lorente L, et al. Association between serum soluble CD40 ligand levels and mortality in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care 2009 13:6. 2011;15:R97. doi: 10.1186/cc10104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lerolle N, et al. von Willebrand factor is a major determinant of ADAMTS-13 decrease during mouse sepsis induced by cecum ligation and puncture. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:843–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peigne V, et al. The prognostic value of ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 repeats, member 13) deficiency in septic shock patients involves interleukin-6 and is not dependent on disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care. 2013;17:R273. doi: 10.1186/cc13115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yin H, et al. Role for platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX and effects of its inhibition in endotoxemia-induced thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and mortality. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2529–2537. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin V, et al. Deletion of the p110 isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in platelets reveals its central role in Akt activation and thrombus formation in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2010;115:2008–2013. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rahman M, Gustafsson D, Wang Y, Thorlacius H, Braun OÖ. Ticagrelor reduces neutrophil recruitment and lung damage in abdominal sepsis. Platelets. 2014;25:257–263. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2013.809520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Le Faouder P, et al. LC–MS/MS method for rapid and concomitant quantification of pro-inflammatory and pro-resolving polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites. Journal of Chromatography B. 2013;932:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file.