Abstract

The synthesis of the high performance inorganic materials essential to the quality of modern day life is hindered by traditionalist attitudes and reliance on outdated methods such as batch syntheses. While continuous flow methods have been extensively adopted in pharmaceutical circles, they remain largely unexplored for the preparation of inorganic compounds, despite higher efficiency, safety and versatility. In this publication, we demonstrate a step-change for the synthesis of metal ammonium phosphates through conversion of the extant batch process to a low-temperature continuous regime, exhibiting a tenfold increase in throughput combined with a significant decrease in particle size.

Introduction

Although inorganic materials are essential to life in the 21st century, advancements in their preparation are underutilised as traditionalist attitudes in academia and particularly industry mean batch processes predominate. Continuous flow synthesis (CFS) is one such alternative technique: it is prevalent in pharmaceutical research1,2, yet has received lesser attention for inorganic synthesis outside of nanomaterials research3. This is largely due to the typically high capital costs associated with flow systems4; despite the technique’s inherent flexibility1,2,4, safety1,2, scalability1,3,5,6, and controllability1–3,7,8. Low temperature (<100 °C), ambient pressure flow syntheses presents an affordable preparative route to a plethora of inorganic materials8–15, without the high capital cost of proprietary systems4. In this communication, we demonstrate a step-change, low-cost continuous preparation of versatile metal ammonium phosphates and derivatives. We compare CFS with the commonly used batch method16 and demonstrate a tenfold increase in throughput combined with a significant reduction in particle size for continuously synthesised particles.

Metal ammonium phosphates (MAPs) and other compounds of the form AMPO4.xH2O (where A+ is Na, K, NH4 and M2+ is a divalent metal such as Mg, Fe or Zn) were first explored in detail by Bassett and Bedwell in the 1930s16. These compounds have since been investigated for a myriad of uses including catalysis17–19, pigments17, fertilisers20, energy storage21, biomaterials8–11, flame retardants17 and as ion exchange materials22–28. Their preparative route, however, has changed little since the initial research16: an inefficient batch precipitation process requiring vast excesses of phosphorus reagent, and extended reaction times (>3 h) at high temperatures (>80 °C) to fully crystallise the product. Hydrothermal and solvothermal routes to MAPs and related compounds have been explored29–33, though these are often as, if not more time, resource and energy intensive than the traditional precipitation route.

Based upon a novel low temperature (<100 °C) ambient pressure continuous flow synthesis of the biomaterials brushite and hydroxyapatite8–11, we adapted the synthesis of MAPs to a continuous mode. Bassett noted that an additional source of NH4+ or performing the precipitation at an elevated pH, can serve to increase the rate of crystallisation of some MAPs16. Through a combination of these factors and the rapid mixing of a continuous flow regime, we are able to reduce the reaction time for preparation of MAPs from a typical 180 minutes down to 7 minutes. An excess of phosphate relative to the metal is required to prevent formation of the undesired M3(PO4)2 phase16,34.

We prepared six MAPs (M = Mg, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni and Zn) and one related hydrogen phosphate (M = Sn) using this technique in a variety of hydration states. Our CFS process provides two feeds: one containing the metal (M2+, 0.05 M) typically as the nitrate salt, and the other a mixture of triammonium phosphate (TAP, 0.25 M) and ammonium nitrate (AN, 0.5 M)8–11. These feeds mix continuously before heating the flow, which serves to crystallise the initially amorphous product8. For some metals (notably Fe and Co), this crystallisation results in a clear colour change. The characterisation data of our MAPs are presented in Table 1, with comparative particle sizes, yields, and throughputs for material produced using the common batch process16. Reaction yields are expressed as a percentage of the theoretical maximum. Throughputs are expressed in grams per litre of liquor per hour, accounting for the reaction time.

Table 1.

Characterisation data for MAPs: reaction yield (%), particle size for flow (CFS) and batch (Bx) produced material as 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles (D10, D50 and D90, µm), BET surface are (m2/g) and observed XRD crystal hydration phase.

| M | XRD Phase | Yield | Particle Size (CFS, um) |

Particle Size (Bx, um) |

Throughput | BET | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (CFS) | (Bx) | % (CFS) | % (Bx) | D10 | D50 | D90 | D10 | D50 | D90 | CFS | Bx | m2/g (CFS) | |

| MgAP* | Mon/Hex | Mon | 94 | 99 | 2.5 | 13.6 | 44.3 | 14.6 | 24.6 | 66.0 | 6.6 | 1.3 | 15.7 |

| MnAP | Mon | Mon | 99 | 99 | 6.4 | 22.8 | 65.1 | 7.4 | 18.4 | 42.2 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 6.8 |

| FeAP | Mon | Mon | 99 | 99 | 2.9 | 9.5 | 23.9 | 15.4 | 52.8 | 108.3 | 8.4 | 1.6 | 49.8 |

| CoAP | Mon | Mon | 97 | 99 | 4.9 | 23.5 | 51.3 | 15.8 | 65.0 | 135.9 | 8.4 | 1.6 | 6.5 |

| NiAP | Hex | Mon | 83 | 99 | 1.3 | 7.7 | 26.6 | 2.6 | 12.1 | 81.4 | 7.1 | 1.6 | 9.5 |

| ZnAP | Anhyd | Anhyd | 98 | 99 | 2.0 | 9.7 | 20.9 | 6.3 | 19.9 | 45.5 | 7.9 | 0.5 | 3.6 |

| SnHP | Anhyd | Anhyd | 79 | 78 | 2.7 | 6.5 | 22.8 | 2.3 | 19.4 | 40.3 | 7.5 | 1.5 | 4.7 |

MgAP (*) required the addition NH3 to the Mg2+ feed in flow to precipitate the desired product8.

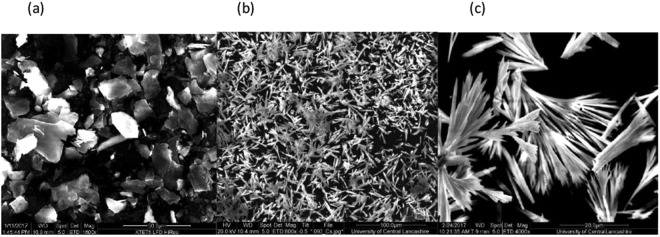

MgAP forms a mixed-phase mono- and hexa-hydrate in CFS, and a monohydrate in batch (Fig. S1)19,35–37. MnAP, FeAP and CoAP are all prepared in the monohydrate dittmarite phase regardless of synthesis method (Figs S2–S4)19,35–37, forming plate-like crystallites (Fig. 1a). NiAP forms the hexahydrate (Fig. S5) struvite-like phase in flow, and the monohydrate in batch34. ZnAP forms an anhydrous phase regardless of synthesis method (Fig. S6)16, forming flower-like crystallites (Fig. 1b). SnHP forms anhydrous rod-like particles (Figs 1c and S7).

Figure 1.

SEM images of FeAP platelets, ZnAP flowers and SnHP rods.

MgAP can interchange between mono- and hexahydrated phases through hydrolysis and dehydration respectively35,38, though our continuous flow process forms a mix of the two phases, though a longer or hotter reaction time fully dehydrates the product. NH3 was added to the Mg2+ feed to prevent formation of MgHPO48. Mn, Fe and CoAP all favour the monohydrated phase and were prepared in this form in both batch and flow16,19,36,37. NiAP can, like MgAP, interconvert between the two phases, though the monohydrate phase is metastable and the synthesis is sensitive to the reaction conditions used34. The NiAP batch sample was of the monohydrate phase as the crystals have sufficient time to dehydrate. No stable ZnAP hydrate has been prepared as the system favours the anhydrous form16. We were unable to synthesise SnAP as hydrolysis of the acidic Sn2+ ion takes precedence over the formation of the desired phase. SnHP is prepared by exchanging the triammonium phosphate for phosphoric acid and omitting the ammonium nitrate. The phases of the batch produced materials match those of the flow produced materials except for NiAP34, which is synthesised as the monohydrate in batch16. Neither CaAP or CuAP can be synthesised via our continuous flow route, as hydroxyapatite39 (for Ca) or a hydroxyphosphate40 (for Cu) form preferentially instead. Bassett noted the difficulty in synthesising CuAP relative to other divalent metals16.

The yields of all our flow process were excellent (>94%) except for NiAP (83%) and SnHP (79%) due to the marginal solubilities of the metals in aqueous ammonia and acid respectively41–43. The yields can be increased through process optimisation. Yields for the batch produced material were quantitative, except for SnHP, where the yield matched the flow produced example. All of our flow produced materials, except MnAP, were at least half the size than the batch produced materials with narrow size distributions. Flow-produced FeAP is less than one fifth the size of equivalent batch material. The reduction in particle size is due to the increased rates of mixing and turbulence within the flow process and our adapted reaction conditions which promote a significant reduction in crystallisation time. For MnAP, the larger sized particles produced in flow are due to increased Ostwald ripening during the crystallisation process44. The observed surface areas of our flow-produced compounds vary with the nature of the crystalline product. FeAP shows a BET high surface area as the plate-like crystals are significantly thinner (Fig. 1a) than those of the similarly plate-like MnAP and CoAP. Throughputs for the CFS process are at least five times that of the batch process, and up to sixteen times for ZnAP due to the lengthy reaction times required in batch16.

The efficiency of the CFS process can be further improved by the feasible regeneration of the effluent liquor. Concentration, replacement of precipitated phosphate and addition of the required NH3 allows for use in further syntheses. Recovery of process heat by pre-heating precursor streams would further increase efficiency. Changing reagent stoichiometry, overall concentrations, and process parameters such as temperature, flow rate and mixing regime would allow for control of particle sizes produced within the CFR45. Use of specialist mixers such as confined impinging jet mixers may also allow for preparation of MAPs on the nanoscale due to more turbulent mixing during the precipitation step45. The flows within our demonstrated system are all laminar.

Conclusions

We have developed an efficient continuous flow synthesis of metal ammonium phosphates and compared this to traditional batch methods. We have demonstrated a step change in the preparation of these compounds as synthesised particles are smaller, more evenly sized and produced with far greater efficiency than previous syntheses. In comparison to the traditional batch methods, we observe up to a tenfold increase in throughput (in terms of mass per unit volume per unit time) with our flow process. This value can be increased further with process optimisation. For many applications, smaller particles are preferably as higher surface areas provide higher activities. Continuous flow synthesis provides this benefit with the option of greater control over particle size and morphology. Through the application of appropriate engineering and chemistry, the syntheses of other key inorganic materials could be improved in a similar manner as demonstrated here.

Experimental

Mg(NO3)2, Mn(NO3)2, (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, Co(NO3)2, Ni(NO3)2, Zn(NO3)2, SnCl2, NH4NO3, H3PO4, NH4OH, and (NH4)2HPO4 were obtained from Fisher Scientific as reagent grade (>98%) quality and used as acquired with no further purification. (NH4)3PO4 was prepared in situ by the addition of excess ammonia to a concentrated solution of (NH4)2HPO4 and gently heating the resultant mixture to 65 °C so as to remove the excess ammonia. The solution was then cooled and diluted to the required concentration. Deionised water (>18 MΩ/cm) was used for all syntheses.

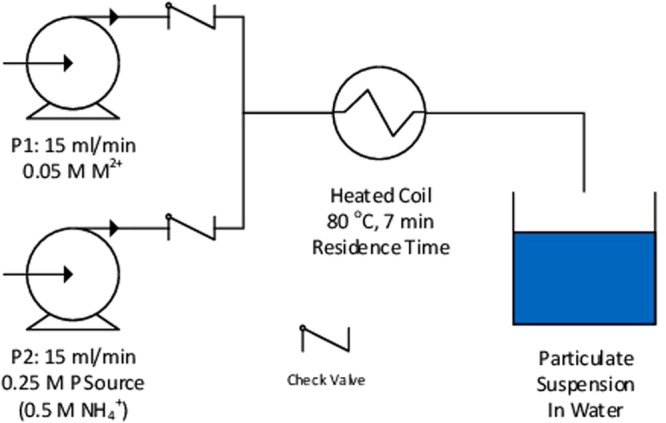

Our continuous flow reactor (CFR) was constructed based on previous literature references8–11. Simply, this consists of two peristaltic pumps (Watson Marlow SciQ 323), a simple Y-mixer and a coil of PVC tubing (16 m length, 4 mm internal diameter, wall thickness 1 mm, total volume 210 cm3) contained within a thermostatically-controlled water bath (Grant JB Aqua 18 Plus). This is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic of CFR.

The rotational rate and thus flow rate of each pump can be varied from 5–40 ml/min, corresponding to a total flow rate of 10 to 80 ml/min and thus a residence time of between 3 and 20 minutes, though a total flow rate of 30 ml/min and thus a residence time of 7 minutes was used in this work. Both pumps were run at the same flow rate in all cases, with one providing the metal salt feed, and the other the phosphorus source and any ancillary reagents. The temperature of the water bath could be varied between ambient and 100 °C. All reactions presented here were performed at 80 °C. A narrow aperture (c.a. 1 mm) at the outlet of the CFR served to even the flow within the system, and check valves after each pump ensured a continuous unidirectional flow. Products were purified by repeated washing with deionised water, and were then dried overnight at 80 °C. The batch syntheses of MAPs were adapted from the work of Bassett and Bedwell16, using the same procedure but scaled to give the same volume of product as in our flow process.

The rate of heating within the process is rapid, as a total flow rate of greater than 120 ml/min emerges from the reactor at 80 °C with the same tubing setup utilised for these syntheses, suggesting that temperature equilibrium is attained within 2 minutes and thus 5 minutes are spent at temperature to allow completion of reaction. Further modelling of this factor is beyond the scope of the research presented here.

Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) analysis was conducted using a Brucker D2 Diffractometer with a copper kα radiation source with data collected between 5 and 80 degrees 2Θ. XRD patterns were converted from proprietary formats using PowDLL46. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and X-Ray Energy Dispersive elemental analysis was conducted under high vacuum using a FEI Quanta 200 scanning electron microscope equipped with an EDAX Sapphire Energy Dispersive X-Ray detector. Surface areas were determined using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) model at 77 K using nitrogen absorption (Micrometrics ASAP2010), with accuracy checked against an alumina standard. Particle size distribution analysis (PSD) was conducted using a Malvern Mastersizer 2000. Samples were sonicated in deionised water before analysis to disperse any agglomerates. Results are expressed as D50, the 50th percentile of particle size.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Mrs T. Garcia-Sorribes, Mr J. C. Donnely and Mr P. Bentley for technical assistance and Prof K. K. Singh and her group for provision of analytical equipment. This work was funded as part of the EPSRC project “Advanced Waste Treatment using Nanostructured Hybrid Composites” EP/M026485/1.

Author Contributions

Principal Investigator of this research was G. Bond, the manuscript was co-written by H. Eccles and A. Holdsworth. Experiments were carried out by A. Holdsworth, with BET experiments carried out by A. Halman. Results were analysed and interpreted by A. Holdsworth and R. Mao.

Data Availability Statement

The data underpinning this publication can be found on https://clok.uclan.ac.uk/.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-31694-x.

References

- 1.Wiles C, Watts P. Continuous flow reactors: a perspective. Green Chem. 2012;14:38–54. doi: 10.1039/C1GC16022B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartman RL, McMillen JP, Jensen KF. Deciding whether to go with the flow: evaluating the merits of flow reactors for synthesis. Angw. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50:7502–7519. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darr JA, Zhang Z, Makwana NM, Weng X. Continuous Hydrothermal Synthesis of Inorganic Nanoparticles: Applications and Future Directions. Chem. Rev. 2017;117(17):1112–11238. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien M, Konings L, Martin M, Heap J. Harnessing open-source technology for low-cost automation in synthesis: Flow chemical deprotection of silyl ethers using a homemade autosampling system. Tetr. Lett. 2017;58(25):2409–2413. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang, S. V. Y. PhD Thesis (University of Nottingham, 2014).

- 6.Johnson ID, et al. High power Nb-doped LiFePO4 Li-ion battery cathodes; pilot scale synthesis and electrochemical properties. J. Pow. Sourc. 2016;302:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.10.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marre, S., Adamo, A., Basak, S., Aymonier, C. & Jensen, K. F. Design and Packaging of Microreactors for High Pressure and High Temperature Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 49, 11310–11320 (2010).

- 8.Chaudhry AA, et al. Instant nano-hydroxyapatite: a continuous and rapid hydrothermal synthesis. Chem. Commun. 2006;21:2286–2288. doi: 10.1039/b518102j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piccirillo, C. et al. Aerosol assisted chemical vapour deposition of hydroxyapatite-embedded titanium dioxide composite thin films. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 332, 45–53 (2017).

- 10.Anwar A, Akbar S, Sadiqa S, Kazmi M. Novel continuous flow synthesis, characterisation and antibacterial studies of nanoscale zinc substituted hydroxyapatite bioceramics. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2016;453:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2016.07.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anwar A, Rehman IU, Darr JA. Low-Temperature Synthesis and Surface Modification of High Surface Area Calcium Hydroxyapatite Nanords Incorporating Organofunctionalised Surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120(51):26069–29076. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b05878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akram M, Saleh AT, Ibrahim WAW, Awan AS, Hussain R. Continuous microwave flow synthesis (CMFS) of nano-sized tin oxide: Effect of precursor concentration. Ceram. Int. 2016;42:8613–8619. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.02.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akram M, et al. Continuous microwave flow synthesis of mesoporous hydroxyapatite. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2015;56:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akram M, et al. Continuous microwave flow synthesis (CMFS) of nanosized titania: Structural, optical and photocatalytic properties. Mater. Lett. 2015;158:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2015.05.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akram M, et al. Continuous microwave flow synthesis and characterisation of nanosized tin oxide. Mater. Lett. 2015;160:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2015.07.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassett, H. & Bedwell, W. L. Studies of phosphates. Part I. Ammonium magnesium phosphate and related compounds. J. Chem. Soc., 854–871 (1933).

- 17.Ayyappan S, et al. Synthesis characterisation and acid-base catalytic properties of ammonium-containing tin(II) phosphates: [NH4][Sn4P3O12] and [NH4][SnPO4] Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 2000;2:21–27. doi: 10.1016/S1466-6049(99)00068-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bogdanova VV, Kobets OI. Synthesis and physiochemical properties of Di- and trivalent metal-ammonium phosphates. Russian. J. Appl. Chem. 2014;87(10):1387–1401. doi: 10.1134/S1070427214100012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Touaiher M, et al. Synthesis and structure of NH4CoPO4.6H2O. Ann. Chim. Sci. Mat. 2001;26(3):49–54. doi: 10.1016/S0151-9107(01)80060-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galkova TN, Pacewska B, Samuskevich VV, Pysiak J, Shulga NV. Thermal transformations of CuNH4PO4.H2O. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2000;60:1019–1032. doi: 10.1023/A:1010184414044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koleva V, Stoyanova R, Zhecheva E, Nihtianova D. Dittmarite precursors for structure and morphology directed synthesis of lithium manganese phosphor-olivine nanostructures. CrystEngComm. 2014;16:7515–7524. doi: 10.1039/C3CE42501K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro F, Ferreira A, Rocha F, Vicente A, Teixeira JA. Continuous-Flow Precipitation of Hydroxyapatite at 37 °C in a Meso Oscillatory Flow Reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013;52:9816–9821. doi: 10.1021/ie400710b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castro F, et al. Continuous-Flow precipitation as a route to prepare highly controlled nanohydroxyapatite: in vitro mineralisation and biological evaluation. Mater. Res. Expr. 2016;3:075404. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/3/7/075404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dikiy NP, et al. Sorption properties of magnesium-potassium phosphate matrix. Probs. Atom. Sci. Tech. 2015;3(97):79–82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borai, E. H., Attallah, M. F., Shehata, F. A., Hilal, M. A. & Abo-Aly, M. M. IAEA report: EG0800311.

- 26.Campayo, L. PhD Thesis (University of Limoges, 2003).

- 27.Borovikova EY, et al. Relationship between IR spectra and crystal structures of b-tridymit-like CsM2+PO4 compounds. Eur. J. Miner. 2012;24:777–782. doi: 10.1127/0935-1221/2012/0024-2209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korchemkin IV, et al. Thermodynamic properties of caesium-manganese phosphate CsMnPO4. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2014;78:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jct.2014.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boudin S, Lii K-H. Ammonium Iron(II,III) Phosphate: Hydrothermal Synthesis and Characterisation of NH4Fe2(PO4)2. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37(4):799–803. doi: 10.1021/ic970655+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satyavani TVSL, Kumar AS, Rao PSVS. Methods of synthesis and performance improvement of lithium iron phosphate for high rate Li-ion batteries: A review. Eng. Sci. Tech. Int. J. 2016;19(1):178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jestch.2015.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirkiukhina GV, Yakubovich OV, Dimitrova OV. Crystal structure of a new polymorphic modification of niahite, NH4MnPO4.H2O. Crystallog. Rep. 2015;60(2):198–203. doi: 10.1134/S106377451502011X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen C, et al. Polypyrrole-Modified NH4NiPO4.H2O Nanoplate Arrays on Ni Foam for Efficient Electrode in Electrochemical Capacitors. ACS Sus. Chem. Eng. 2016;4(10):5578–5584. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b01347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S, et al. NH4CoPO4.H2O microbundles consisting of one-dimensional layered microrods for high performance supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 2014;4:340–347. doi: 10.1039/C3RA45977B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goni A, et al. Synthesis, crystal structure and spectroscopic properties of the NH4NiPO4.nH2O (n = 1, 6) compounds; magnetic behaviour of the monohydrated phase. J. Mater. Chem. 1996;6(3):421–427. doi: 10.1039/JM9960600421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frost RL, Weier ML, Erickson KL. Thermal decomposition of struvite. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2004;76(3):1025–1033. doi: 10.1023/B:JTAN.0000032287.08535.b3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greedan JE, Reubenbauer J, Birchall T, Ehlert M. A magnetic and Mossbauer study of the layered compound (NH4)Fe(PO4).H2O. J. Solid State Chem. 1988;77:376–388. doi: 10.1016/0022-4596(88)90261-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carling SG, Day P, Visser D. Crystal and Magnetic Structures of Layer Transition Metal Phosphate Hydrates. Inorg. Chem. 1995;34:3917–3927. doi: 10.1021/ic00119a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarkar AK. Hydration/dehydration characteristics of struvite and dittmarite pertaining to magnesium ammonium phosphate cement systems. J. Mater. Sci. 1991;26:2514–2518. doi: 10.1007/BF01130204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monma H, Kamiya T. Preparation of hydroxyapatite by the hydrolysis of brushite. J. Mater. Sci. 1987;22:4247–4250. doi: 10.1007/BF01132015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US. Pat. 3201195 (Aug 1965).

- 41.Van Bommel A, Dahn JR. Analysis of the Growth Mechanism of Coprecipitated Spherical and Dense Nickel, Manganese and Cobalt-Containing Hydroxides in the Presence of Aqueous Ammonia. Chem. Mater. 2009;21:1500–1503. doi: 10.1021/cm803144d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clungston M, Flemming R. Advanced Chemistry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salhi R, Boudjouada M, Messikh S, Gherraf N. Recovery of nickel and copper from metal finishing hydroxide sludge by kinetic acid leaching. J. New Tech. Mater. 2016;6(2):62–81. doi: 10.12816/0043935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.LaMer VK, Dinegar RH. Theory, Production and Mechanism of Formation of Monodispersed Hydrosols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950;72(11):4847–4854. doi: 10.1021/ja01167a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pieper M, Aman S, Hintz W, Tomas J. Optimization of a Continuous Precipitation Process to Produce Nanoscale BaSO4. Chem. Eng. Tech. 2011;34(9):1567–1574. doi: 10.1002/ceat.201000405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kourkoumelis, N. ICDD Annual Spring Meetings, Ed. O’Neill, L. Powder Diffraction, 28, 137–148 (2013).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underpinning this publication can be found on https://clok.uclan.ac.uk/.