Abstract

Background

Anaphylaxis is the most serious manifestation of an immediate allergic reaction and the most common emergency event in allergology. Adrenaline (epinephrine) is the mainstay of acute pharmacotherapy for this complication. Although epinephrine has been in use for more than a century, physicians and patients are often unsure and inadequately informed about its proper administration and dosing in everyday situations.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications from the period 1 January 2012 to 30 September 2017 that were retrieved, on the basis of the existing guidelines of 2007 and 2014, by a PubMed search employing the keywords “anaphylaxis treatment,” “allergic shock,” “adrenaline,” and “epinephrine,” as well as on further articles from the literature.

Results

Adrenaline/epinephrine administration often eliminates all manifestations of anaphylaxis. The method of choice for administering it (except in intensive-care medicine) is by intramuscular injection with an autoinjector; this is mainly done to treat reactions of intermediate severity. The injection is given in the lateral portion of the thigh and can be repeated every 10–15 minutes until there is a response. The dose to be administered is 300–600 µg for an adult or 10 µg/kg for a child. The risk of a serious cardiac adverse effect is lower than with intravenous administration. There have not been any randomized controlled trials on the clinical efficacy of ephinephrine in emergency situations. The use of an autoinjector should be specially practiced in advance.

Conclusion

The immediate treatment of patients with anaphylaxis is held to be adequate, yet major deficiencies remain in their further diagnostic evaluation, in the prescribing of emergency medications, and in patient education. Further research is needed on cardiovascular involvement in anaphylaxis and on potential new therapeutic approaches.

Anaphylaxis is the maximal variant of an acute life-threatening immediate-type allergy and represents the most common and often life-threatening emergency situation in allergology. In contrast to hay fever, asthma, and atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis), few reliable epidemiological studies exist of the prevalence rates of anaphylactic reactions (1).

Background

In tandem with the general increase in allergic disorders in the population, anaphylactic reactions have become more common, not only in Europe (2– 4), but also in the USA and Asia (5– 7), for example from 16/100 000 person-years in 2008 to 32/100 000 person-years in 2014 (5). With a total prevalence of 42/100 000 person-years in the period from 2001 to 2010, Lee et al. observed an annual increase of 4.3% and, for food-induced anaphylaxis, of 9.8% (6).

In particular, food-induced anaphylaxis in children has increased—for example, from 41/100 000 emergency admissions in 2007 to 72/100 000 such admissions in 2012 (7).

Often, patients with allergic rhinitis (hay fever) also react to allergens that occur in foodstuffs and pollen grains (“pollen-associated food allergies”).

A classic example are people with allergies to birch pollen, who also react with anaphylaxis to hazelnuts, because they have developed IgE antibodies to the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1, which occurs in many foodstuffs.

Reactions to Bet v 1 homologous proteins are altogether common, but they rarely trigger severe reactions (8).

In view of the numerous triggers and the multiple possibilities for exposure over a lifetime, lifetime prevalence rates of anaphylaxis in the population have been estimated to be 0.3–15%; in some studies this also includes milder reactions, such as externally triggered acute urticaria (9– 11).

Methods

On the basis of the available guidelines from 2007 and 2014 we conducted a selective literature search in PubMed, using the search terms “anaphylaxis treatment”, “allergic shock”, “adrenaline”, and “epinephrine” for the period from 1 January 2012 to 30 September 2017. We also took recourse to literature we ourselves collected over time.

Clinical symptoms

Anaphylactic reactions are accompanied by a multitude of symptoms affecting different organs, which sometimes occur in succession and sometimes simultaneously—but not necessarily always to the same degree.

In most cases (80–90%), the reactions start with subjective general symptoms and skin manifestations (for example, urticaria/hives 62%, angioedema 53%), sometimes accompanied by formication on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Advanced symptoms include nausea of the gastrointestinal tract in 24% of those affected, colic-type pain in 16%, vomiting in 27%, and diarrhea in 5%.

The respiratory tract is affected in 49%. Those affected experience dyspnea, either as a narrowing of the upper airway in the sense of laryngeal edema or as asthmatic bronchial constriction (35%).

Anaphylaxis can affect the cardiovascular system—for example, by triggering tachycardias or blood pressure fluctuations in up to 42% of cases. These can be so comprehensive that anaphylactic shock may ensue (12– 15) (box).

BOX. The most important symptoms of anaphylaxis*.

-

Subjective general symptoms (known in the past as prodromal symptoms)

Restlessness

Abnormal tiredness in children

Paresthesias or itching of palms, soles of feet, or in anogenital region

Metallic or fishy taste in the mouth

Visual disturbances

Feelings of anxiety

-

Skin

Generalized pruritus

Disseminated weals (urticaria, hives)

Circumscribed tissue swellings (angioedema, e.g. of the eyelids, lips)

Episodic reddening (flushing)

-

Gastrointestinal tract

Nausea, vomiting

Stomach cramps, colic

Diarrhea, voiding of feces and/or urine

-

Airways

Rhinoconjunctivitis

Dyspnea

Wheezing

Asthma attack

Blocking of upper trachea, glottal edema (a feeling of obstruction of the throat)

Respiratory arrest

-

Cardiovascular system

Palpitations and tachycardia

Drop in blood pressure

Collapse, circulatory shock, cardiac arrhythmia

Anaphylaxis can affect the same patient to different degrees of intensity, which is considered in the classification into grades of clinical severity (16, 17).

Pathophysiology

During the trigger phase of anaphylaxis, mast cells and basophils, which release highly active mediator substances, are of central relevance. The best known substance is histamine (18). Furthermore, eicosanoids—such as leukotrienes and prostaglandins—but also platelet activating factor (PAF) have important roles, which are, however, not fully understood just yet.

Further to activation by antibodies, anaphylaxis can be triggered non-immunologically by direct mediator release or complement activation.

The causes of a fatal outcome are mostly (19, 20):

Circulatory shock

Cardiogenic shock as a result of cardiac arrest (also arrhythmia, myocardial infarction)

Obstruction of the upper airway (laryngeal edema)

Severe asthma attack with bronchoconstriction.

Triggers and allergens

The most important triggers of anaphylaxis in adults are insect venom, foods, and medicines, whereas in children, it’s foods (table 1).

Table 1. Common triggers of anaphylaxis*.

| Insect venom (n = 2074) | |

| Wasp | 1460 |

| Bee | 412 |

| Hornet | 93 |

| Bumblebee | 5 |

| Horsefly | 4 |

| Mosquito | 4 |

| Foods (n = 1039) | |

| Pulses (including peanut) | 241 |

| Animal proteins | 225 |

| Nuts | 199 |

| Grains | 101 |

| Fruits | 65 |

| Vegetables | 63 |

| Herbs/spices | 55 |

| Additives | 13 |

| Others | 17 |

* The data come from an anaphylaxis registry. which collects voluntary notifications from the German-speaking region. They therefore do not represent a population-based epidemiological data collection

(modified from [16])

In addition, so called non-specific summation or augmentation factors are relevant, if a reaction is triggered only after simultaneous effects of other, often non-specific factors plus contact with the allergen (1, 21– 24), as for example:

Physical exercise/exertion

Administration of medications (acetylsalicylic acid, beta blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, and others)

Acute infections

Psychological stress

Alcohol use

Simultaneous exposure to different allergens.

Acute treatment

The basic principles of emergency treatment have been described in national and international guidelines (14, 25, 26).

General measures

General measures include:

Interrupting delivery of the allergen

Positioning the patient in a way that is appropriate for their symptoms

Diagnostic evaluation of vital signs

Prompt insertion of an intravenous cannula and administration of fluids as required

Providing oxygen and appropriate cardiopulmonary resuscitation if required (27).

Medication therapy

Adrenaline/epinephrine is of central importance in the setting of pharmacotherapy. Antihistamines (H1-antagonists) are used in mild reactions and glucocorticoids are given in order to prevent late phase reactions.

Adrenaline/epinephrine has been in use for more than 100 years. The consensus is that it is effective in treating anaphylaxis, even though—in the sense of evidence-based medicine—placebo controlled prospective studies are lacking. Such studies would not be ethically justifiable in any case (14, 26).

Mechanism of action of adrenaline/epinephrine

Adrenaline/epinephrine is one of three endogenous catecholamines, which is produced alongside noradrenaline in the adrenal glands and released in a scenario of stress, like cortisone. In combination with other blood pressure raising systems—for example, the renin-angiotensin system—this forms the basis for the spontaneous resolution of symptoms in many cases. Adrenaline binds to catecholamine receptors, but its specificity is dose-dependent: at low dosages, beta 1 and beta 2 receptor effects dominate, the effects mediated by alpha and beta receptors are balanced only at moderate dosages. At high dosages, vasoconstriction—mediated by alpha receptors—plays a greater part (table 2) (28).

Table 2. Pharmacological effects of adrenaline/epinephrine in the treatment of anaphylaxis*.

| Adrenergic receptor | Function |

| α1 adrenergic receptor | – Increased vasoconstriction – Increased peripheral vascular resistance – Raised blood pressure – Reduction of tissue edema (e.g.. larynx) – Nasal vasoconstriction |

| α2 adrenergic receptor | – Lowering intraocular pressure |

| β1 adrenergic receptor | – Raised heart rate (positive chronotropic) – Increased cardiac contraction (positive inotropic) – Vasoconstriction in skin and mucosa |

| β2 adrenergic receptor | – Bronchodilation – Vasodilation – Inhibition of mediator release – Lowering peripheral blood pressure |

| β3 adrenergic receptor | – Promotion of lipolysis |

* modified from (8)

Because of these effects, adrenaline/epinephrine is used in non-allergic states too—for example, for the purpose of vasoconstriction in local surgery, to treat symptoms after intubation, and in croup or false croup.

The anti-anaphylactic effect of adrenaline/epinephrine is primarily due to the stimulation of alpha and beta receptors. The alpha adrenergic receptors are responsible for vasoconstriction in the area of the precapillary arterioles of the skin, mucosa, and kidneys and smooth muscle contraction in the venous vascular bed, which results in increases in peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure. Subsequently, any tissue edema that has developed as a result of the increased vascular permeability reduces (29). Concomitantly, adrenaline/epinephrine dilates via beta-2 adrenergic receptors the bronchi and vasculature especially in the skeletal muscles.

Stimulation of the beta adrenergic receptors increases the heart rate and contractility of the cardiac muscle while simultaneously expanding the coronary arteries. The result is an increased output of the heart, accompanied by increased oxygen consumption. Increased cardiac output in turn raises the systolic blood pressure. At higher concentrations and with rapid administration (for example, if given intravenously), adrenaline/epinephrine can have an arrhythmogenic effect. At high concentrations, the contracting effect of the alpha receptors on the coronary vessels can exceed the dilating effect of the beta-2 receptors and lead to cardiac necroses (28, 30). By activating beta-2 receptors and increasing intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), the mediator release from effector cells is downregulated.

The effects of adrenaline/epinephrine in the different receptors are dose-dependent and are affected by non-specific other factors—for example, hypoxia, acidosis, age, or chronicity of stimulation (28, 30, 31).

Adrenaline/epinephrine antagonizes crucial pathogenetic mechanisms that are involved in the development and degree of anaphylaxis:

Hypovolemia as a result of peripheral vasodilation and loss of volume in tissue

Respiratory failure due to bronchoconstriction or mucosal edema in the upper airway

Cardiac arrest due to the negative inotropic effect of the mediator substances.

Other catecholamines

Noradrenaline or dopamine are in individual cases used in the intensive care setting for severe reactions, especially if the desired result is an increase in the alpha adrenergic receptor effect and blood pressure (26).

Application of adrenaline/epinephrine

Adrenaline/epinephrine can be administered via different routes (table 3) (26, 32– 34, e1– e3). The application method is determined by the degree of severity and the circumstances of the anaphylactic event. Intravenous application—recommended as the method of choice for many decades—is mainly the preserve of the intensive care setting. It is given as a diluted solution of an original concentration of 1 mg/mL (proprietary product Suprarenin, diluted 1:10 or 1:100) and is administered cautiously and slowly while pulse and blood pressure are monitored.

Table 3. Application routes of adrenaline/epinephrine and associated advantages and disadvantages in the treatment of anaphylaxis*1.

| Application route | Advantages and disadvantages |

| Oral | Rapid inactivation owing to catechol-O-methyltransferase and monoamine oxydase |

| Sublingual | Only in scientific studies |

| Inhaled | If laryngeal edema is the main symptom |

| Intranasal | Currently under scientific study |

| Intratracheal | In intubated patients |

| Subcutaneous | Slowl effect. poor resorption |

| Intramuscular | Method of choice in the initial phase of anaphylaxis. especially for self medication |

| Intravenous | Risk of overdose if given too quickly. problem of dilution. absolutely indicated in grade IV (cardiac and/or respiratory arrest) |

| Intracardiac | In cardiopulmonary resuscitation*2 |

Most anaphylactic emergencies occur outside the hospital or practice setting, for example as a result of insect stings/bites or food ingestion. In such situations, immediate intramuscular application of adrenaline/epinephrine is the method of choice, best administered with an autoinjector (0.15–0.5 mg). The injection should be placed on the outside of the thigh (into the vastus lateralis muscle). If the patient shows no response, a repeat injection can be given every 10–15 minutes, depending on effects and adverse effects.

Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that plasma concentrations of adrenaline/epinephrine return to adequate levels very rapidly after intramuscular application. This systemic availability occurs much faster than after inhalation or subcutaneous application (34, 37). At the same time, the risk of overdose and thus of severe cardiac adverse effects is lower than after intravenous application.

No prospective controlled studies exist of the clinical effectiveness in the emergency setting. Dhami et al., in a systematic review of the available evidence, found some indications for the effectiveness of adrenaline/epinephrine in registries and case series, which they themselves did not rate as very strong (16, e1, e4). They also point out that owing to the methodological problems inherent in investigating the treatment of anaphylactic shock, no better evidence is likely to become available in the foreseeable future. However, what is also clear is that people still die from anaphylactic shock even after they have received adrenaline/epinephrine (e5). Furthermore, no definite association exists between the severity of the anaphylactic reaction and the extent of previous episodes of anaphylaxis. In spite of the positive indications and the plausibility of an effect of adrenaline/epinephrine, intramuscular application is slow to be adopted in Germany; even in severe reactions (grades III and IV [26]), adrenaline/epinephrine is given as the initial measure in only 20% of cases (Figure).

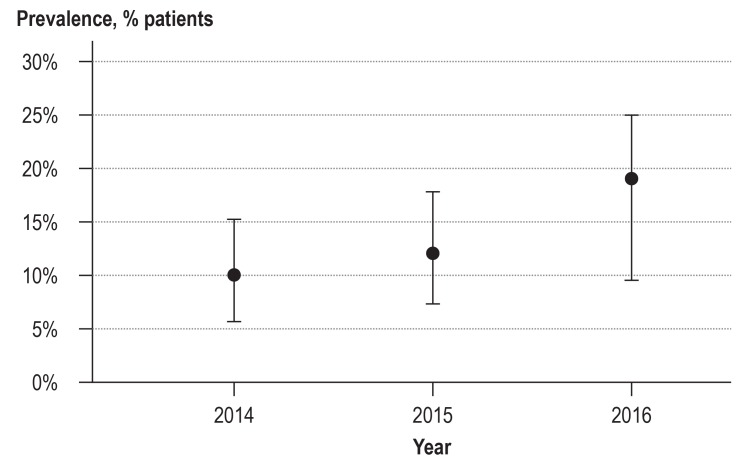

Figure 1.

First-line treatment by intramuscular application of adrenaline/epinephrine in patients with severe anaphylaxis (grades III and IV [26]) in 2014–2016.

Data from the German language anaphylaxis registry (Worm et al., personal communication)

Dosage

As stated before, controlled efficacy studies are lacking, and, similarly, there are no dose-finding studies either. Handbooks recommend dosages of 300–600 µg/person in adults, which corresponds to about 5–10 µg/kg body weight and to 10 µg/kg body weight in children. In adults, it has been found successful to start with 300 µg and in children (body weight 7.5–25 kg), with 150 µg, with subsequent doses adapted to the development of clinical symptoms.

In patients with a high body weight (>100 kg), the initial dose should be 500 µg. The length of the needle is also important, in order to avoid injecting into a fat layer that is too thick and in order to reach the muscle.

The effect of the adrenaline/epinephrine can be quickly assessed within very few minutes. The therapeutic range is small. The effects of the adrenaline/epinephrine are experienced by patients immediately and may lead to states of anxiety, restlessness, palpitations, pallor, shaking, and headache. These symptoms are associated with the desired therapeutic effect of adrenaline/epinephrine, and patients should familiarize themselves with them if they wish to self medicate.

The risk of overdose or adverse effects in childhood is low, but it is imperative to consider this in adults and older patients with underlying cardiovascular disorders (e3). On the other hand, patients with coronary heart disease are particularly endangered by anaphylactic reactions; sufficient perfusion pressure in the coronary circulation is often made possible only by simultaneous administration of fluid volume and vasoconstrictors (e3).

Adrenaline/epinephrine autoinjector for self-medication

After the successful acute treatment of anaphylaxis, prophylaxis is the next most important therapeutic objective. This requires a well-informed patient, appropriate diagnostic evaluations for determining the allergic trigger, and an “emergency kit for immediate first aid” for self-medication until an emergency physician is available.

The center piece of this emergency kit is an adrenaline/epinephrine autoinjector (23, 33, 35). This is a pre-dosed injector pen (EpiPen in the USA), which is conceived for use by a medical layperson. If handled correctly—and patients need to learn how to use it correctly—the pen will release the adrenaline/epinephrine solution directly into the muscle through an automatically extending/protruding needle. At the present time, three different preparations are available in Germany, which differ in dose, length of needle, and release mechanism.

The different autoinjectors require different handling. Either only a protective cap covering the needle will have to be removed or, additionally, a safety cap from the opposite end of the pen. Handling these will need to be learnt by training on dummies (36, 37, e6, e7). For this reason, proprietary names matter, and autoinjectors should not be randomly swapped, such as happens for generic preparations (38, 39).

It is not possible to replace via discount contracts a prescribed autoinjector with another one without consent from the prescribing doctor.

Patients also need to practice handling their fear in the emergency situation. This vastly exceeds the available timeframe of a consultation between doctor and patient. For this reason, the working group “Anaphylaxie Training und Edukation” (AGATE e. V., a non-profit association without any competing commercial interests) has developed a standardized, quality assured education program (anaphylaxis training, www.anaphylaxieschulung.de), which specially trained experts provide on a nationwide basis. This is the only training program whose effectiveness was evaluated in a prospective randomized trial (40); some health insurers reimburse patients on application.

For patients, avoiding the allergenic trigger is crucial, but this can be difficult, especially in food allergies, and requires the collaboration of an allergologically trained dietician (a list is available from “Deutscher Allergie- und Asthmabund,” the German association for asthma and allergies, reg. assoc., www.daab.de).

Problems

Current problem with autoinjectors relate to their availability—for example, in nurseries or schools; often, two autoinjectors are prescribed, which is also the recommendation of the European Medicines Agency (36).

In our opinion, special indications exist regarding the prescription of a second autoinjector (16, 26, 32, e8):

A high body weight

Particular risks for developing anaphylaxis (for example, mastocytosis)

Severe previous anaphylaxis

Long distance between residence and primary medical care facility

Childhood age (nursery/school).

Adrenaline in an aqueous solution can be subject to chemical instability, even if the pH is low and with sulfite.

After the use-by date, the solution gradually loses effectiveness, even though it stays clear and colorless. If no other autoinjector is available, such a solution can be applied (27, e9).

The treatment of patients who take betablockers is complicated (e3), since adrenaline/epinephrine does not reach the downregulated receptors in adequate amounts. In the acute case scenario, the recommendation is for intravenous administration of glucagon to upregulate the beta adrenergic receptors. Most guidelines recommend the application of adrenaline in pregnancy in case of anaphylaxis (26, e10).

The main problem for many of those affected is the fact that they are not prescribed an autoinjector. A study from Belgium showed that acute treatment was given with excellent results in a large hospital, but that only 9% of anaphylaxis patients received an invitation for allergy testing or were given an adrenaline/epinephrine autoinjector (33). Similar data were collected in 1995 in Munich, Germany, when emergency physician callouts were analyzed. Back then, 70 patients with severe anaphylaxis after insect stings/bites were treated highly successfully—all survived, but only 10% received information on further management or even an emergency kit (e11).

Glucocorticoids and antihistamines have their place in mild (grade I) reactions (26, e9, e11).

Conclusion

The medical care of patients with anaphylaxis is generally positive. Substantial gaps exist, however, in the further diagnostic evaluation, prescription of emergency medication, and instruction and training (e4). The situation provides an opportunity to raise awareness among physicians of the problem of anaphylaxis and of providing affected patients with the option to use an autoinjector to inject adrenaline/epinephrine into the muscle as a self-medication method, as well as giving the necessary medical advice.

Key Messages.

Anaphylaxis as the extreme variant of an immediate allergic reaction is potentially life-threatening and represents the most important emergency in allergology.

In addition to the general measures used to tackle shock, adrenaline/epinephrine is the cornerstone of acute treatment. It can be administered in various ways, ideally by immediate intramuscular injection. Intravenous application in diluted form is the preserve of intensive care.

Patients are given an emergency kit for the purpose of self-medication. This contains an antihistamine, glucocorticoid, and adrenaline/epinephrine autoinjector, whose use needs to be learnt and practiced.

Several autoinjectors are available, which differ in dose, shelf life, length of needle, and application technique/use. For this reason, these preparations are not simply interchangeable.

After successful acute treatment, patients will have to be given sufficient information and be referred for further diagnostic evaluation, in order to determine the trigger, so that further/future contact can be avoided. Education programs, such as an anaphylaxis training program for patients or their parents, have been found to be useful.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Acknowledgment

We thank the following for their help and expertise in composing the manuscript: Beyer K. (Berlin), Biedermann T. (Munich), Brockow K. (Munich), Fischer J. (Tübingen), Jung K. (Erfurt), Kopp M.V. (Lübeck), Lange L. (Bonn), Niggemann B. (Berlin), Rietschel E. (Cologne), Schnadt S. (Mönchengladbach).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Ring received consultancy fees from ALK, HAL, Meda Pharma, and Mylan.

Prof Klimek received consultancy fees from Mylan.

Prof Worm received consultancy fees and payments for scientific lectures from Meda Pharma, Allergopharma, and ALK-Abelló.

References

- 1.Ring J, editor. Anaphylaxis. Basel: Karger. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan DP, Anderson HR. Time trends in allergic disorders in the UK. Thorax. 2007;62:91–96. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.038844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheikh A on behalf of the EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Group. The epidemiology of anaphylaxis in Europe: a systematic review. Allergy. 2013;68:1353–1361. doi: 10.1111/all.12272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonia-Pinto B, Fonseca JA, Gomes ER. Frequency of self-reported drug allergy A systematic review and metaanalysis with metaregression. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang MS, Kim JY, Kim BK, et al. True rise in anaphylaxis incidence: epidemiological study based on a national health insurance database. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005750. e5750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Hess EP, Lohse C, Gilani W, Chamberlain AM, Campbell RL. Trends, characteristics and incidence of anaphylaxis in 2001-2010: A population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parlaman JP, Oron AR, Uspal NG. Emergency and hospital care for food-related anaphylaxis in children. Hospital Pediatrics. 2016;6:262–274. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worm M, Edenharter G, Rueff F, et al. Symptom profile and risk factors of anaphylaxis in Central Europe. Allergy. 2012;67:691–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moneret-Vautrin DA, Morisset M, Flabbee J, Beaudouin E, Kanny G. Epidemiology of life-threatening and lethal anaphylaxis: a review. Allergy. 2005;60:443–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ring J, Bachert C, Bauer CP, Czech W (eds.) Weißbuch Allergie in Deutschland. Springer, Urban & Vogel GmbH. (3) 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panesar SS, Javad S, de Silva D, et al. The epidemiology of anaphylaxis in Europe: a systematic review. Allery. 2013;68:1353–1361. doi: 10.1111/all.12272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grabenhenrich LB, Dölle S, Moneret-Vautrin A, et al. Anaphylaxis in children and adolescents: The European Anaphylaxis Registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1128–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genovese A, Rossi FW, Spadaro G, Galdiero MR, Marone G. Human cardiac mast cells in anaphylaxis. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2010;95:98–109. doi: 10.1159/000315945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons FE, Ardusso LR, Bilo MB, et al. World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guide-lines: summary. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Worm M, Moneret-Vautrin A, Scherer K, et al. First European data from the Network of Severe Allergic Reactions (NORA) Allergy. 2014;69:1397–1404. doi: 10.1111/all.12475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Worm M, Eckermann O, Dölle S, et al. Triggers and treatment of anaphylaxis: an analysis of 4000 cases from Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:367–375. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ring J, Grosber M, Brockow K. Anaphylaxieerkennung, Notfallbehandlung und Management. Arzneimitteltherapie. 2016;34:112–119. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. Anaphylaxis: mechanisms of mast cell activation. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2010;95:45–66. doi: 10.1159/000315937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pumphrey R. Anaphylaxis: can we tell who is at risk of a fatal reaction? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:285–290. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000136762.89313.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pumphrey RSH, Roberts ISD. Postmortem findings after fatal anaphylactic reactions. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:273–276. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.4.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hompes S, Dölle S, Grünhagen J, Grabenhenrich L, Worm M. Elicitors and co-factors in food-induced anaphylaxis ibn adults. Clin Transl Allergy. 2013;3 doi: 10.1186/2045-7022-3-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niggemann B, Beyer K. Factors augmenting allergic reactions. Allergy. 2014;69:1582–1587. doi: 10.1111/all.12532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nassiri M, Babina M, Dölle S, Edenharter G, Rueff F, Worm M. Ramipril and metoprolol intake aggravate human and murine anaphylaxis: evidence for direct mast cell priming. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zink A, Ring J, Brockow K. Kofaktorgetriggerte Nahrungsmittelanaphylaxie. Allergologie. 2014;37:258–264. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muraro A, Roberts G, Worm M, et al. Anaphylaxis guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 2014;69:1026–1045. doi: 10.1111/all.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ring J, Beyer K, Biedermann T, et al. Leitlinie zu Akuttherapie und Management anaphylaktischer Reaktionen. Allergo J Int. 2014;23:96–112. doi: 10.1007/s40629-014-0009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deutscher Rat für Wiederbelebung (eds.) Reanimatiion 2015 - Leitlinie kompakt. 2015:132–153. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westfall TC, Westfall DP. Adrenergic agonists and antagonists Goodman Gilman’s pharmacological basis of therapeutics. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC, editors. Mc Graw Hill. New York: 2011. pp. 272–334. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann BB. Catecholamines, sympathomimetic drugs and adrenergic receptor antagonists Goodman & Gilman: The pharmaceutical basis of therapeutics. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Goodman A., Mc Graw Hill, editors. New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotecchia S. The alpha 1 adrenergic receptor: diversity of signaling network and regulation. J Receptor Signal Transduct Res. 2010;30:410–419. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2010.518152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santulli G, Iaccarino G. Adrenergic signaling in heart failure and cardiovascular aging. Maturitas. 2016;93:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klimek L, Sperl A, Worm M, Ring J. Notfallset und Akutbehandlung der Anaphylaxie Das muß der Hausarzt über den allergischen Schock wissen. MMW Fortschr Med. 2017;53:74–80. doi: 10.1007/s15006-017-9600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mostmans Y, Grosber M, Blykers M, Mols P, Naeije N, Gutermuth J. Adrenalin in anaphylaxis treatment and self-administration: experiences from an inner city emergency department. Allergy. 2017;72:492–497. doi: 10.1111/all.13060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simons FE, Gu X, Simons KJ. Epinephrine absorption in adults: intramuscular versus subcutaneous injection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:871–873. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fromer L. Prevention of anaphylaxis: the role of the epinephrine auto-injector. Amer J Medicine. 2016;129:1244–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.European Medicines Agency. Better training tools recommended to support patients using adrenalin auto-injectors. 26 June 2015 EMA/ 411622/2015 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guerlain S, Hugine A, Wang L. A comparison of 4 epinephrine autoinjector delivery systems: usability and patient preference. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klimek L. Adrenalin-Autoinjektoren bei Anaphylaxie - als Sprechstundenbedarf verordnungsfähig? Allergo-Journal. 2017;26:54–55. [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNeil C, Copeland J. Accidental digital epinephrine injection: to treat or not to treat? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:726–728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brockow K, Schallmayer S, Beyer K, et al. Effects of a structured educational intervention on knowledge and emergency management in patients at risk for anaphylaxis. Allergy. 2015;70:227–235. doi: 10.1111/all.12548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Huang F, Chawla K, Järvinen KM, Nowak-Weegrzyn A. Anapylaxis in a New York City pediatric emergency department: Triggers, treatments, and outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Srisawat C, Nakponetong K, Benjasupattananun P, et al. A preliminary study of intranasal epinephrine administration as a potential route for anaphylaxis treatment. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2016;34:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Brown MJ, Brown DC, Murphy MB. Hypokalemia from beta-2-receptor stimulation by circulating epinephrine. N Eng J Med. 1983;309:1414–1419. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312083092303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Dhami S, Panesar S, Roberts G, et al. Management of anaphylaxis: a systematic review. Allergy. 2014;69:168–175. doi: 10.1111/all.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Pumphrey RSH, Gowland MH. Correspondence (letter to the editor): Further fatal allergic reactions to food in the United Kingdom 1999-2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1018–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Brockow K, Beyer K, Biedermann T, et al. Versorgung von Patienten nach Anaphylaxie - Möglichkeiten und Defizite. Allergo J Int. 2016;25:160–168. [Google Scholar]

- E7.Wölbing F, Biedermann T. Anaphylaxis: opportunities of stratified medicine for diagnosis and risk assessment. Allergy. 2013;68:1499–1508. doi: 10.1111/all.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Brockow K, Jofer C, Behrendt H, Ring J. Anaphylaxis in patients with mastocytosis: a study on history, clinical features and risk factors in 120 patients. Allergy. 2008:226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01569.x. a63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Simons FE, Gu X, Simons KJ. Outdated EpiPen and EpiPen Jr auto-injectors: past their prime? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:1025–1030. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Simons FE, Schatz M. Anaphylaxis during pregnancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Bresser H, Sander CH, Rakoski J. Insektenstichnotfälle in München. Allergo J. 1995;4:373–376. [Google Scholar]

- E12.Liyanage CK, Galappatthy P, Seneviratne SL. Corticosteroids in management of anaphylaxis; a systematic review of evidence. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immuno. 2017;49:196–207. doi: 10.23822/EurAnnACI.1764-1489.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]