Abstract

Qualitative evidence suggests that husbands’ inequitable gender equity (GE) ideologies may influence associations between husbands’ alcohol use and intimate partner violence (IPV) against wives. However, little quantitative research exists on the subject. To address this gap in the literature, associations of husbands’ elevated alcohol use and GE ideologies with wives’ reports of IPV victimization among a sample of married couples in Maharashtra, India, were examined. Cross-sectional analyses were conducted using data from the baseline sample of the Counseling Husbands to Achieve Reproductive Health and Marital Equity (CHARM) study. Participants included couples aged 18 to 30 years (N = 1081). Regression models assessed the relationship between husbands’ elevated alcohol use and GE ideologies (using the Gender-Equitable Men [GEM] Scale) and wives’ history of physical and/or sexual IPV victimization ever in marriage. Husbands and wives were 18 to 30 years of age, and married on average of 3.9 years (SD ± 2.7). Few husbands (4.6%) reported elevated alcohol use. Husbands had mean GEM scores of 47.3 (SD ± 5.4, range: 35–67 out of possible range of 24–72; least equitable to most equitable). Approximately one fifth (22.3%) of wives reported a history of physical and/or sexual IPV. Wives were less likely to report IPV if husbands reported greater GE ideologies (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 0.97, 95% CI [0.95, 0.99]), and husband’s elevated alcohol use was associated with increased risk of IPV in the final adjusted model (AOR: 1.89, 95% CI [1.01, 3.40]). Findings from this study indicate the need for male participation in violence intervention and prevention services and, specifically, the need to integrate counseling on alcohol use and GE into such programming.

Keywords: alcohol use, gender equity attitudes, IPV

Trial Registration: NCT01593943 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01593943)

Over the past 20 years, researchers have aimed to understand how men’s endorsement of key masculine ideologies relates to men’s health and whether endorsement of traditional ideas of masculinity results in protective or risk behaviors (Harrison, 1978; Levant & Wimer, 2013; Levant, Wimer, & Williams, 2011). Connell’s theory of masculinity has been used widely to connect the relationship between masculine ideologies and health (Nascimento & Connell, 2017). Research from numerous global contexts identify strong relationships between men’s endorsement of traditional masculine ideologies and health behaviors, such as alcohol and drug consumption (Levant & Wimer, 2013; Levant, Wimer, & Williams, 2011; Mahalik et al., 2005), and unhealthy relationship factors such as intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration against female partners. Connell’s theory of masculinity describes masculinity as “the practices through which men and women engage … in gender, and the effects of these practices on bodily experience, personality and culture.” (Connell, 1995, p. 71). In particular, Connell’s concept of hegemonic masculinity (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005) has been linked to men’s IPV perpetration against female partners (Moore & Stuart, 2005), which often occurs as a result of challenges to traditional masculine ideologies (O’Neil, Helms, Gable, David, & Wrightsman, 1986).

Research from India reinforces the theory that negative behaviors take place within the context of conflicting masculine and gender ideologies. India is characterized by social norms and practices that link the concept of masculinity with men’s dominance over women (Jejeebhoy & Sathar, 2001; Nanda et al., 2014). Nanda and colleagues found that IPV is more likely to occur in situations where wives challenge typical gender roles and can be seen as threatening husbands’ masculinity (Nanda et al., 2014; Pulerwitz, Michaelis, Verma, & Weiss, 2010). For example, social norms related to husbands’ roles in family structures in India revolve around the masculine ideology that husbands are the key decision makers within families (Kishor & Gupta, 2009; Nanda et al., 2014; Pulerwitz et al., 2010). Such societal norms encourage masculine ideologies and unequal gender norms and reinforce Connell’s conceptualization of hegemonic masculinity (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Though Connell’s theory of masculinity includes the perspective that hegemonic masculinity can only be achieved by “white men,” the concept of hegemonic masculinity may be applied within the Indian context. As Dasgupta and Gokulsing (2013) describe, it is important to consider how hegemonic masculinity manifests in various cultures. The authors argue that one manifestation of hegemonic masculinity is in patriarchy and socially reinforced power dynamics. India, with its long history of clashes in caste, religion, and class, which stem from decades of colonialism, has strong roots in patriarchy. Research from India examining associations between men’s endorsement of masculine ideologies (i.e., support for inequitable gender norms) and IPV victimization of their female partners documents that husbands who support inequitable gender norms are significantly more likely to report IPV perpetration against their female partners (Nanda et al., 2014; R. Verma et al., 2008). Social expectations of wives, which are often accepted by both men and women, dictate that wives produce children (with a preference for sons) early in marriage, solely take care of children and domestic duties at home, not refuse sex from husbands, and respect their in-laws (Ghule et al., 2015; Kishor & Gupta, 2009; Nanda et al., 2014). These examples all relate to Connell’s conceptualization of hegemonic masculinity.

IPV is a pervasive public health issue (World Health Organization [WHO], 2005). Women contending with IPV are at heightened risk for physical and mental health problems including both acute and long-lasting physical injury, depression, and poor sexual and reproductive health outcomes (WHO, 2005, 2012). Married women account for a large proportion of IPV victimization in India; 40% of wives report experiences of physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime (International Institute for Population Sciences [IIPS] & Macro International, 2007). Determinants of IPV involve factors operating at individual, relationship, community, and societal levels (WHO, 2012). Indian wives who have a high number of children, lower education, belong to low wealth quintiles, and whose husbands consume alcohol are at heightened risk for IPV (Kishor & Gupta, 2009).

Qualitative research conducted with men in urban Maharashtra indicates that alcohol use enhances masculine ideologies related to sexual violence with female partners (e.g., the right to have sex with wives). This research also illustrates how men face social pressure to adhere to traditional masculine ideologies related to alcohol consumption through drinking alcohol during festivals (not drinking alcohol was compared to being a “gud” [feminine boy]; R. K. Verma et al., 2006; R. Verma & Schensul, 2004). These findings indicate the importance of considering the larger social context, which may influence husbands’ endorsement of unequal gender norms as it relates to husbands’ alcohol use.

The association between husbands’ heavy drinking and IPV victimization of wives is well established globally (WHO, 2012; Wilson, Graham, & Taft, 2014) and in India (Berg et al., 2010; Chandrasekaran, Krupp, George, & Madhivanan, 2007; Go et al., 2003; Jeyaseelan et al., 2007; Kishor & Gupta, 2009; Sarkar, 2008; Stanley, 2008). Analysis of national data from India indicates that women with husbands who are heavy alcohol drinkers are two to three times more likely to report IPV victimization compared to wives whose husbands are not heavy drinkers (Kishor & Gupta, 2009). Berg and colleagues (Berg et al., 2010) conducted a mixed methods study to understand how societal norms influence the relationship between husbands’ alcohol use and IPV perpetration in India, which confirmed prior research documenting associations between husbands’ alcohol use and IPV perpetration against female partners. The study presented findings from qualitative interviews with wives of husbands who drink alcohol, documenting triggers for IPV, which included asking husbands about drinking, refusing to give husbands money for alcohol, suspicion that wives are not faithful, domestic issues around cooking, and not having children at the expected time. The findings from Berg and colleagues (Berg et al., 2010) illustrate how challenging traditional societal gendered norms may influence or exacerbate wives’ risk for IPV victimization within the context of husbands’ heavy drinking. However, no quantitative data exist to test these relationships.

Additional research testing similar associations suggest that wives with husbands who consume alcohol regularly are almost six times more likely to report experiences of physical IPV victimization (Jeyaseelan et al., 2007). Research outside of India examining the relationship between husbands’ alcohol use and IPV suggest that alcohol use results in lowering inhibitions that may prevent men from restraining themselves from IPV perpetration. Alcohol, which can act as a mood enhancer, may also increase the likelihood of husbands being easily angered or frustrated (Wilson et al., 2014). Given the negative effect of alcohol on individuals’ problem-solving abilities, conflict in the context of alcohol use is common (Sayette, Wilson, & Elias, 1993). Furthermore, even in situations where husbands’ alcohol use does not necessarily cause IPV perpetration, research from 13 countries highlight that IPV perpetration against wives is most severe within the context of husbands’ alcohol use (Graham, Bernards, Wilsnack, & Gmel, 2011).

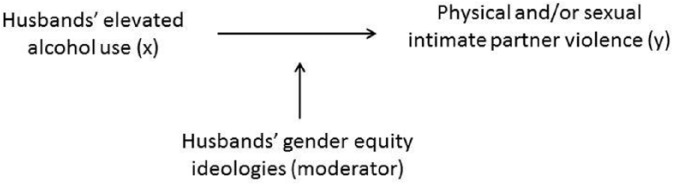

While many have assessed the relationship between husbands’ alcohol use and IPV perpetration, and separately between husbands’ endorsements of unequal gender norms and IPV perpetration in India, research examining how men’s positive endorsements of unequal gender norms may impact the relationship between alcohol use and IPV perpetration is lacking (Figure 1). The current study among a sample of married couples in rural Maharashtra, India, aims to build on these existing studies to better understand how these factors relate. This analysis (a) tests associations of husbands’ alcohol use and endorsements of low GE ideologies using the Gender-Equitable Men (GEM; Pulerwitz et al., 2010) Scale with physical and/or sexual IPV experienced by wives ever in marriage, and (b) assesses whether endorsements of low GE ideologies by husbands alters the relationship between husbands’ alcohol use and wives’ reports of IPV victimization. Based on existing literature, it is hypothesized that husbands’ endorsement of poor GE may moderate associations between husbands’ alcohol use and IPV perpetration against wives (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Moderation analysis examining if men’s gender equity ideologies moderate the association between husbands’ elevated alcohol use and wives’ intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization.

Methods

Study Population

This study involved analysis of cross-sectional data from participants in the Counseling Husbands to Achieve Reproductive Health and Marital Equity (CHARM) study. The CHARM intervention, a male-centered family planning study, was evaluated via a two-armed cluster randomized control trial in Maharashtra, India. Study participants (N = 1,081) were assessed by quantitative survey assessment at baseline, and 9 and 18 months after baseline. Baseline data from this study were used for the current analyses.

Between March and December 2012, trained research staff approached households to identify young married men between 18 and 30 years of age within the selected clusters. If a married couple with a man in the specified age range was home, research staff provided details regarding participation in the CHARM intervention and evaluation study. If the couple indicated interest in participating, sex-matched research staff would conduct the informed consent process separately with each member of the couple in a private space in the house. Once the informed consent process was complete, couples were screened for eligibility. Eligibility criteria included being 18 to 30 years of age, fluent in Marathi, residing with the spouse in the cluster area for the past 3 months, plans to stay in the cluster for another 2 years, and no sterilization for either the man or his wife. Men and women were excluded based on sterilization, given that study participants would potentially enroll in an intervention to increase the use of family planning methods. Research staff screened 1,881 couples; of the couples screened, 1,143 were eligible to participate in the study (60.8% eligibility rate), and 1,081 eligible couples chose to participate in the study (94.6% participation rate).

After the couples completed eligibility screening and informed consent procedures, sex-matched research staff administered a 60-min paper survey to husbands and wives separately. Survey items covered a broad range of topics including demographics, sexual history, IPV, and GE attitudes. No monetary incentives were provided, based on guidelines set by in-country institutional review boards (IRBs). All study procedures were approved by the IRBs at the appropriate institutions (institution names removed for review process). In addition, all study staff adhered to WHO guidelines for ethical research on domestic violence (WHO, 2001) to ensure safety of both study participants and research staff. Note: Details on collection of baseline data (including safety measures) and the CHARM intervention study are described in full in the study protocol paper (Yore et al., 2016).

Measures

Sociodemographics included age and education for husbands and wives, husband’s caste, family’s monthly income, and wife’s working status. Age and education data were based on husbands’ and wives’ reports of their own information. Age was kept as a continuous variable for analysis. Education was measured by a single item asking individuals the number of years of schooling they completed (continuous measure). Caste and family income were based on husbands’ reports, as women tend to take their husbands’ caste (if different than their own) after marriage and husbands tend to control family finances in these contexts. Caste was measured based on four separate categories of “scheduled caste, scheduled tribe, other backward class, none of these.” The caste variable was created with the following categories: “scheduled caste/tribe” and “backward class/none.” Couples belonging to scheduled castes or scheduled tribes represent greater socioeconomic marginalization relative to those belonging to either other backward class or none (not belonging to a scheduled caste, tribe, or other backward class). Wives’ responses were used to understand wives’ working status, based on if they were engaged in any income-generating activities (dichotomous yes/no).

Marital characteristics were based on wives’ reports of length of time married (i.e., marital length) and number of living children. Marital length was a continuous variable (measured in years) calculated by taking the difference between the participants’ current age and age at marriage (based on the question “How old were you when you first got married?”). This variable was used descriptively in analyses (and not as a covariate for the multivariate analysis). Number of births involved women’s reports of how many living sons and daughters they had delivered, the number of sons and daughters they had who had been born alive and later died, and the number of stillbirth experiences. These items were combined to create a continuous measure reflecting total number of births reported by wives.

The outcome of interest for these analyses was physical and/or sexual IPV victimization, reported ever in marriage by wives. This dichotomous variable was based on an 8-item measure asking women how frequently they experienced different forms of violence, based on validated measures from the third wave of the National Family Health Survey (IIPS & Macro International, 2007). The questions had response categories of “often,” “sometimes,” “not at all” (meaning not in the past 6 months), and “never in our relationship” (meaning never experiencing violence in the relationship). The following forms of violence perpetrated by husbands were included: (a) slapping, (b) arm twisting and pulling hair, (c) pushing, shaking, and throwing something at her, (d) kicking, dragging, beating up, (e) choking or trying to burn, (f) threaten to attack with knife, gun, or weapon, (g) forced sexual intercourse, and (h) forced to perform sexual acts against her will. Women’s endorsement of “often,” “sometimes,” or “not at all” to any of the items were categorized as “yes” for the IPV variable (responses of “never in our relationship” were categorized as “no”). These items had strong internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.98).

The primary independent variables were men’s GE ideologies and husbands’ elevated alcohol use, as reported by men. GE ideologies were measured by the GEM Scale (Pulerwitz & Barker, 2008). This scale was developed for use in Brazil but it has been translated, adapted, and reported to be a reliable measure for use in six different countries, including India (R. K. Verma et al., 2006). GEM includes 24 items measuring male gender ideology related to sexual and reproductive health, sexual relations, domestic violence, domestic responsibilities, and homophobia. Men were read a series of statements and then asked if they “agree,” “partially agree,” or “do not agree” with each statement. Each item was scored with the least equitable response scoring 1, moderately equitable responses scoring 2, and the most equitable responses scoring 3, thus resulting in a possible range of 24 to 72 (least equitable to most equitable). The scale was kept as a continuous measure and had an acceptable level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.70) to be used for a measure of masculine ideology (Streiner & Norman, 2008).

Husbands’ drinking in the past month was assessed by a single self-report measure asking husbands how many days in the past 30 days they had four or more drinks on one occasion. Husbands reporting 1 or more days of drinking with four or more drinks on one occasion in the past month were categorized as “potentially being at elevated risk of alcohol-related problems” or “elevated alcohol use” (individuals who reported 0 days were categorized as not having any days in the past month with “elevated alcohol use” or “no”). The categorization of this variable is a more stringent definition of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s (NIAAA’s) definition of “heavy drinking” (5 or more drinks on the same occasion; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2016) and the widely used alcohol measure Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C; United States Department of Veterans Affairs, 2016). The majority of participants self-identified as belonging to “tribal” populations, where many men primarily drink a home-brewed heavily concentrated liquor. As a result, using a more stringent measure to assess elevated drinking is most appropriate for this cultural setting.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses (frequencies and proportions) were conducted on all demographic indicators, marital characteristics, GE ideologies, alcohol use, and IPV variables. Pearson’s χ2 tests of independence and analyses of variance (for continuous variables with the categorical variable outcome) were calculated to assess differences between all demographic and independent variables with the outcome of IPV. In an effort to better understand how husbands in the present sample endorsed certain constructs of the GEM scale, individual statements included in the GEM scale were examined descriptively to understand proportions of husbands’ positive endorsements (“agree” or “partially agree”) of each statement (these data are presented in Table 2).

Table 2.

Endorsement (Agree or Partially Agree) and Associations of Gender-Equitable Men (GEM) Scale Items Among Husbands in Maharashtra, India (N = 1,081).

| GEM Scale items | Total sample N = 1,081 N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sexual relationships | |

| It is the man who decides what type of sex to have. | 913 (84.5%) |

| Men need sex more than women do. | 930 (86.0%) |

| You don’t talk about sex, you just do it. | 860 (79.6%) |

| A man needs other women, even if things with his wife are fine. | 163 (15.1%) |

| Men are always ready to have sex. | 955 (88.3%) |

| A man should know what his partner likes during sex.a | 1,071 (99.1%) |

| Violence | |

| There are times when a woman deserves to be beaten. | 671 (62.1%) |

| If a woman cheats on a man, it is okay for him to hit her. | 884 (81.8%) |

| If someone insults me, I will defend my reputation, with force if I have to. | 1,057 (97.8%) |

| It is okay for a man to hit his wife if she won’t have sex with him. | 366 (33.9%) |

| A woman should tolerate violence in order to keep her family together. | 926 (85.7%) |

| Domestic life | |

| A woman’s most important role is to take care of her home and cook for her family. | 1,041 (92.3%) |

| Changing diapers, giving kids a bath, and feeding the kids are the mother’s responsibility. | 1,005 (93.0%) |

| A man should have the final word about decisions in his home. | 943 (87.2%) |

| It is important that a father is present in the lives of his children, even if he is no longer with the mother.a | 1,073 (99.3%) |

| Reproductive and sexual health | |

| Women who carry condoms on them are “easy.” | 822 (76.0%) |

| It is a woman’s responsibility to avoid getting pregnant. | 766 (70.9%) |

| I would be outraged if my wife asked me to use a condom. | 299 (27.7%) |

| A couple should decide together if they want to have children.a | 1,066 (98.6%) |

| In my opinion, a woman can suggest using condoms just like a man can.a | 1,025 (94.8%) |

| If a guy gets a woman pregnant, the child is the responsibility of both.a | 1,073 (99.3%) |

| A man and woman should decide together what type of contraceptive to use.a | 1,071 (99.1%) |

| Relations with other men | |

| I would never have a gay friend. | 1,045 (96.7%) |

| It is important to have a male friend that you can talk about your problems with.a | 949 (87.8%) |

Items recoded to indicate unidirectional pattern of scoring (agree or partially agree = lower gender equity).

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models assessed husbands’ GE ideologies and husbands’ elevated alcohol use in relation to wives’ reports of IPV victimization to allow testing for main effects. Collinearity of all independent variables was assessed to ensure that collinear independent variables were not included in the regression analyses. Variables significant in the unadjusted models were included in the adjusted regression models. Adjusted analyses controlled for education for husbands and wives, number of live births, and husbands’ elevated alcohol use. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to assess size and significance of associations. Note: The measure included in regression analyses to understand GE ideologies was a continuous measure. Next, the second research question to see if men’s GE ideologies moderate the association between husbands’ elevated alcohol use and wives’ IPV victimization was tested (Figure 1). A categorical interaction term between husbands’ alcohol use and GE ideologies was created to understand if husbands’ GE ideologies moderate associations between husbands’ elevated alcohol use and wives’ IPV victimization. Main effects were first tested, followed by analyses inclusive of interaction terms and all covariates. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, U.S.A.).

Results

Demographic and Marital Characteristics

Husbands and wives were aged 18 to 30 years. (See Table 1.) Wives were on average 22.5 years old (SD ± 2.5); husbands were slightly older (26.2, SD ± 2.7). Husbands also had more years of education than women (7.3, SD ± 3.7 for husbands, compared to 6.4, SD ± 4.2 for wives). The vast majority (72.8%, n = 787) of the population belonged to a scheduled caste or tribe (most marginalized group). Most wives (77.2%, n = 834) were not engaged in any income-generating activities. Couples were married 3.9 years on average (SD ± 2.7), with a range of 0 to 14 years. Wives reported 1.3 births (SD ± 1.0) on average; almost one quarter (24.3%, n = 263) had more than two births.

Table 1.

Profiles of Married Women Living in Rural Maharashtra: Demographic, Marriage, and Fertility Characteristics Based on Women’s Reports of Physical and/or Sexual IPV (N = 1,081).

| Variable | Total sample N = 1,081 |

Physical/sexual IPV n = 359 |

No physical/sexual IPV n = 722 |

F-statistic (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables (mean, SD, range) | ||||

| Wives’ age | 22.5, 2.5, 18–30 | 22.5, 2.4, 18–30 | 22.5, 2.5, 18–30 | 1.70 (.06) |

| Husbands’ age | 26.2, 2.7, 18–30 | 26.1, 2.6, 20–30 | 26.2, 2.7, 18–30 | 2.11 (.01)* |

| Wives’ years of education | 6.4, 4.2, 0–17 | 6.1, 4.2, 0–15 | 6.6, 4.2, 0–17 | 1.18 (.28) |

| Husbands’ years of education | 7.3, 3.7, 0–17 | 6.9, 4.0, 0–17 | 7.5, 3.6, 0–17 | 2.09 (.01)* |

| Husbands’ caste (n [%]) | ||||

| Scheduled caste/tribe | 787 (72.8%) | 271 (75.5%) | 516 (71.5%) | 1.96 (.17)a |

| Backward class/none | 294 (27.2%) | 88 (24.5%) | 206 (28.5%) | |

| Wives’ income generation [n (%)] | ||||

| No | 834 (77.2%) | 275 (76.6%) | 559 (77.4%) | 0.09 (.76)a |

| Yes | 247 (22.8%) | 84 (23.4%) | 163 (22.6%) | |

| Marital length (years) | 3.9, 2.7, 0–14 | 4.2, 2.7, 0–13 | 3.8, 2.6, 0–14 | 1.57 (.08) |

| Marriage and fertility characterization (mean, SD, range) | ||||

| Number of births | 1.3, 1.0, 0–8 | 1.4, 1.1, 0–8 | 1.2, 1.0, 0–5 | 1.74 (.10) |

| Masculinity ideologies (GEM scale)b | 47.3, 5.4, 35–67 | 47.6, 5.5, 38–67 | 47.2, 5.4, 35–66 | 1.37 (.08) |

| Husbands’ elevated alcohol use, past 30 days (n [%]) | ||||

| Yes (1+ days) | 46 (4.3%) | 23 (6.4%) | 23 (3.2%) | 6.11 (.02) a* |

| No (0 days) | 1035 (95.7%) | 336 (93.6%) | 699 (96.8%) | |

Note. GEM = Gender-Equitable Men; IPV = intimate partner violence.

Pearson’s χ2 (p value). bHigher score indicates greater gender equity.

p ≤ 0.05.

Husbands’ Elevated Alcohol Use and GE Ideologies

A small proportion of husbands reported elevated alcohol use (4 or more drinks on 1 occasion) on 1 or more days in the past month (4.3%, n = 46). However, there was a larger proportion of husbands reporting past month elevated alcohol use among wives reporting IPV victimization, relative to wives reporting no IPV victimization (6.4% n = 23/359 vs. 3.2%, n = 722). In terms of GE ideologies, husbands scored 47.3 (SD ± 5.4) on average, with scores ranging from 35 to 67 (note: Lower scores indicate lower support of equitable gender ideologies, possible range for scores: 24–72; see Table 1). Husbands had similar average scores across groups of wives reporting IPV victimization (47.6, SD ± 5.5, range: 38–67) and not reporting IPV victimization (47.2, SD ± 5.4, range: 35–66). A review of endorsement of GE ideologies by item indicated three items in the scale where less than 60% of husbands endorsed gender inequity attitudes: “A man needs other women, even if things with his wife are fine” (15.1%, n = 163); “It is okay for a man to hit his wife if she won’t have sex with him” (33.9%, n = 366); “I would be outraged if my wife asked me to use a condom” (27.7%, n = 299; see Table 2).

Intimate Partner Violence

Less than one quarter (22.3%, n = 359) of wives reported experiencing physical and/or sexual IPV in marriage. Significant differences between those reporting IPV victimization and those reporting no IPV victimization were seen for husbands’ age (f = 2.11, p = .01), husbands’ years of education (f = 2.09, p = .01), and husbands’ elevated alcohol use (f = 6.11, p = .02).

Associations Between Husbands’ Alcohol Use, GE Ideologies, and IPV

Table 3 presents unadjusted and adjusted associations between husbands’ alcohol use, GE ideologies, and IPV perpetration. In the unadjusted regression models, husbands’ elevated alcohol use was associated with increased likelihood of wives reporting experiences of IPV (odds ratio [OR]: 2.08, 95% CI [1.15, 3.76]). This association held after controlling for covariates (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.89, 95% CI [1.03, 3.46]). While unadjusted associations between husbands’ GE ideologies and IPV perpetration were not significant after adjusting for covariates (OR: 0.99, 95% CI [0.96, 1.01]), husbands’ GE ideologies were significantly associated with wives’ reports of IPV victimization (AOR: 0.97, 95% CI [0.95, 0.99]), where wives were less likely to report experiencing IPV if husbands reported greater GE (i.e., higher GEM scores indicating greater GE). For every point increase in GE ideology (GEM scale), women were 3% less likely to report experiences of IPV. The moderation analyses identified no significant associations between the interaction term of husband’s elevated alcohol use and GE ideologies and wives’ experiences of IPV in the unadjusted analyses (OR: 1.00, 95% CI [1.00, 1.01], p < .01. Therefore husbands’ alcohol use did not moderate the relationship between husbands’ elevated alcohol use and wives’ reports of IPV victimization.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Logistic Regression Associations Between Husbands’ Masculinity Ideologies and Physical/Sexual IPV (Ever in Marriage) Among Married Women Living in Rural Maharashtra (N = 1,081).

| Variable | OR [95% CI]) | AORa [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| Masculinity ideologies (GEM) | 0.99 [0.96, 1.01] | 0.97 [0.95, 0.99]* |

| Husbands’ elevated alcohol use | 2.08 [1.15, 3.76]* | 1.89 [1.03, 3.46]* |

| GEM × husbands’ alcohol | 1.00 [1.00, 1.01] | 0.97 [0.88, 1.07] |

| Wives’ age | 1.00 [0.95, 1.05] | − |

| Husbands’ age | 1.02 [0.97, 1.07] | − |

| Wives’ education | 1.03 [1.00, 1.06] | 1.01 [0.97, 1.04] |

| Husbands’ education | 1.04 [1.01, 1.08]* | 1.05 [1.00, 1.10] |

| Husbands’ caste (scheduled caste/tribe) | 1.23 [0.92, 1.64] | − |

| Wives’ working status | 0.96 [0.71, 1.29]) | − |

| Number of births | 0.87 [0.77, 0.99]* | 0.93 [0.81, 1.06] |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; GEM = Gender-Equitable Men.

Adjusted for education (husbands and wives), number of births, and husbands’ elevated alcohol use (husbands’ reports). *p ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

The present findings bring greater understanding of how husbands’ elevated alcohol use and GE ideologies may be associated with wives’ experiences of IPV. Specifically, the current findings indicate that husbands who are potentially at elevated risk for alcohol-related problems are more likely to have wives who report IPV victimization, and husbands with more equitable gender norms are less likely to have wives who report IPV victimization. Contrary to the a priori hypothesis, husbands’ GE ideologies did not moderate associations between husbands’ elevated alcohol use and wives’ IPV victimization. However, the present findings, which identify a relationship between IPV victimization of wives, husbands’ GE ideologies (Nanda et al., 2014; R. Verma et al., 2008), and elevated alcohol use (Berg et al., 2010; Chandrasekaran et al., 2007; Go et al., 2010; Stanley, 2008), are consistent with the existing literature and indicate the need to integrate GE counseling into social services reaching men.

Married women report some of the highest rates of IPV victimization in India (IIPS & Macro International, 2007). As evidenced by the present study findings, the social construct of marriage within this Indian context may present opportunities for inequitable gender ideologies to manifest as acts of violence. In particular, as discussed, violence often occurs in marriage when traditional gender roles (e.g., wives taking care of domestic duties) are challenged (Kishor & Gupta, 2009; Nanda et al., 2014). Furthermore, findings from this study support existing understanding that violence perpetrated against women relates to the adoption of ideologies that reinforce violence as a means of control of women (Nanda et al., 2014; Pulerwitz et al., 2010). Use of the GEM scale in the present analyses allows for the inclusion of many aspects (sexual relationships, violence, domestic life, reproductive and sexual health, relations with other men) of the construct of masculinity within rural India. These various dimensions reflect Connell’s conceptualization of multiple masculinities (Connell, 1995); the statements included in the GEM scale represent the beliefs and practices to which men are expected to adhere. Existing qualitative studies on the subject (Pulerwitz et al., 2010; R. K. Verma et al., 2006) provide context for these results. In their study, Verma and colleagues (R. K. Verma et al., 2006) reported that men in India mainly viewed their roles in relationships with women as revolving around male entitlement and dominance. Interventions focused on reducing IPV among married couples must not just prioritize inclusion of men but also focus on changing norms around masculine ideologies.

Findings from the present study also highlight the relationship between husbands’ elevated alcohol use and IPV victimization of wives, which is consistent with the existing literature (Berg et al., 2010; Chandrasekaran et al., 2007; Go et al., 2003; Sarkar, 2008; Stanley, 2008; R. K. Verma et al., 2006; R. Verma & Schensul, 2004). In these analyses, husbands’ elevated alcohol use was independently associated with wives’ IPV victimization, after controlling for all other factors (including GE ideologies). Given the high rates of alcohol use among tribal populations in rural Maharashtra (2008), it is clear that husbands’ problem drinking must also be addressed in an effort to reduce violence against wives. Based on the findings that wives of husbands who espoused greater GE were less likely to report experiencing IPV, there may be potential benefit to incorporating GE counseling into existing alcohol treatment services with men. Most programming aimed at reducing poor health outcomes related to gender inequalities have focused on women (Nanda et al., 2014). However, given men’s positioning as key decision makers across multiple facets of domestic life within Indian households (Jejeebhoy & Sathar, 2001; Nanda et al., 2014), it is imperative that men be included in interventions aimed at reducing gender inequity and IPV (Nanda et al., 2014; Sen & Östlin, 2007). While this approach does not appear to be in practice currently, previous literature reviews suggest its potential utility (Schensul, Singh, Gupta, Bryant, & Verma, 2010).

The analysis to understand if husbands’ GE ideologies moderated the relationship between husbands’ elevated alcohol use and wives’ IPV victimization did not yield significant results. Though the main effects were significant, the lack of significance of the moderation analysis suggests that the association between husbands’ elevated alcohol use and IPV does not vary based on husbands’ GE ideologies. It is possible that significant associations were unable to be detected due to low levels of alcohol use by husbands in this study. Further, lack of inclusion of appropriate measures for heavy drinking (in contrast to a measure that was used in previous studies [Berg et al., 2010; Stanley, 2008] to test associations between husbands’ alcohol use and IPV perpetration) may have also led to null findings. Considering the substantial qualitative evidence linking these factors together, future research should focus on better understanding of the potential moderating effect of men’s GE ideologies on associations between husbands’ alcohol use and wives’ IPV victimization. Research utilizing mixed (quantitative and qualitative) methods may not just prove useful to quantitatively test these relationships but also qualitatively provide the context for the specific mechanism through which these relationships may or may not occur. For example, it is possible that men in the present study may use alcohol as a method to cope with other stressors in their lives, which may also cause them to exhibit violent behavior toward their wives.

The results of the present study must be considered with the following limitations. Given that the study involves analysis of cross-sectional data without information on temporal sequence of events, causal relationships between husbands’ GE ideologies and wives’ IPV victimization cannot be understood. Further, based on the time frames for IPV (ever in marriage) and elevated alcohol use (in the past 30 days) for husbands, it is not possible to understand if husbands’ alcohol use preceded IPV or if it was co-occurring. The construct of elevated alcohol use included in this study has limitations. First, while the construct is based on NIAAA guidelines, the measure used in this study did not strictly adhere to the NIAAA definition of heavy drinking due to consideration of how alcohol is used within the study population (primarily tribal population among whom creation and consumption of local liquor is common). However, the present analyses offer one of the first studies to examine issues of husbands’ alcohol use to understand husbands’ masculine ideologies and wives’ IPV victimization and should be considered as a starting point for this body of literature. All data were collected using in-person survey data collection methodology and as a result may be subject to social desirability bias. This may have resulted in underreporting of IPV experiences by wives, and GE ideology endorsements and problem drinking by husbands. However, given that sex-matched research staff conducted data collection, biases related to gendered responses were minimized (specifically important for reporting GE ideologies and IPV). The results of this study characterize husbands’ elevated alcohol use, GE ideologies, and wives’ reports of IPV victimization among married couples in rural Maharashtra, India, and should not be considered as representative for the country as a whole. Further, data for this study came from a family planning intervention study designed specifically for young heterosexual couples, and the findings must be considered within this context.

Findings from the current study build on the existing literature focused on integrating GE counseling through male engagement interventions to reduce violence against women in India. Research also highlights the importance of integrating alcohol dependence treatment into IPV perpetration prevention programs for men (Easton & Crane, 2016). This study’s focus on married couples presents a novel understanding of how gendered issues relate to IPV within marriage. It is vital that men be included in these efforts to reduce violence against women, through integration of GE counseling approaches within existing social service structures reaching men.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the efforts of the CHARM research team for their support and cooperation. We would also like to acknowledge the men and women who graciously participated in the CHARM study. We wish to thank them for their time, participation, and sharing their stories with our team.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: We wish to acknowledge our funding agencies—National Institutes of Health: National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32DA023356 and T32DA037801), Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (BT/IN/US/01/BD/2010), and National Institute of Child Health and Development (R01HD61115 and R01HD084453).

References

- Berg M. J., Kremelberg D., Dwivedi P., Verma S., Schensul J. J., Gupta K., … Singh S. K. (2010). The effects of husband’s alcohol consumption on married women in three low-income areas of Greater Mumbai. AIDS and Behavior, 14(Suppl 1), S126–S135. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9735-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran V., Krupp K., George R., Madhivanan P. (2007). Determinants of domestic violence among women attending an human immunodeficiency virus voluntary counseling and testing center in Bangalore, India. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, 61(5), 253–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W. (1995). Masculinities. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W., Messerschmidt J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19, 829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta R. K., Gokulsing K. M. (2013). Introduction: Perceptions of masculinity and challenges to the Indian male. In Dasgupta R., Gokulsing K. M. (Eds.), Masculinity and its challenges in India: Essays on changing perceptions (pp. 5–26). Jefferson, NC: Jefferson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Easton C., Crane C. A. (2016). Interventions to reduce intimate partner violence perpetration among people with substance abuse disorders. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(5), 533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghule M., Raj A., Palaye P., Dasgupta A., Nair S., Saggurti N., … Donta B. (2015). Barriers to use contraceptive methods among rural young married couples in Maharashtra, India: Qualitative findings. Asian Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 5(6), 18–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go V. F., Johnson S., Bentley M., Sivaram S., Srikrishnan A. K., Celentano D. D., Solomon S. (2003). Crossing the threshold: Engendered definitions of socially acceptable domestic violence in Chennai, India. Culture, Health, & Sexuality, 5(5), 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Go V. F., Srikrishnan A. K., Salter M. L., Mehta S., Johnson S. C., Sivaram S., … Celentano D. D. (2010). Factors associated with the perpetration of sexual violence among wine-shop patrons in Chennai, India. Social Science & Medicine, 71(7), 1277–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K., Bernards S., Wilsnack S. C., Gmel G. (2011). Alcohol May not cause partner violence but it seems to make it worse: A cross national comparison of the relationship between alcohol and severity of partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(8), 1503–1523. doi: 10.1177/0886260510370596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J. (1978). Warning: The male sex role may be dangerous to your health. Journal of Social Issues, 34(1), 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) & Macro International. (2007). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India: Volume II. Mumbai: IIPS. [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy S., Sathar Z. (2001). Women’s autonomy in India and Pakistan: The influence of religion and region. Population and Development Review, 27(4), 687–712. [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan L., Kumar S., Neelakantan N., Peedicayil A., Pillai R., Duvvury N. (2007). Physical spousal violence against women in India: Some risk factors. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39(5), 657–670. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007001836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishor S., Gupta K. (2009). Gender equality and women’s empowerment in India. Calverton, MD: ICF. [Google Scholar]

- Levant R. F., Wimer D. J. (2013). Masculinity constructs as protective buffers and risk factors for men’s health. American Journal of Men’s Health, 8(2), 110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant R. F., Wimer D. J., Williams C. M. (2011). An evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Health Behavior Inventory-20 (HBI-20) and its relationships to masculinity and attitudes towards seeking psychological help among college men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 11, 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik J. R., Locke B. D., Ludlow L. H., Diemer M. A., Scott R. P. J., Gottfried M., … Stuart G. L. (2005). A review of the literature on masculinity and partner violence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6, 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda P., Gautam A., Verma R., Khanna A., Khan N., Brahme D., … Kumar S. (2014). Study on masculinity, intimate partner violence and son preference in India. New Delhi: International Center for Research on Women. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento M., Connell R. (2017). Reflecting on twenty years of Masculinities: An interview with Raewyn Connell. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 22(12), 3975–3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2016). Drinking levels defined. Retrieved April 22, 2016. Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

- O’Neil J. M., Helms B., Gable R., David L., Wrightsman L. (1986). Gender role conflict scale: College men’s fear of femininity. Sex Roles, 14, 335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J., Barker G. (2008). Measuring attitudes toward gender norms among young men in Brazil: Development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM scale. Men and Masculinities, 10(3), 322–338. [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J., Michaelis A., Verma R., Weiss E. (2010). Addressing gender dynamics and engaging men in HIV programs: Lessons learned from horizons research. Public Health Reports, 125(2), 282–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar N. N. (2008). The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 28(3), 266–271. doi: 10.1080/01443610802042415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette M. A., Wilson G. T., Elias M. J. (1993). Alcohol and aggression: A social information processing analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 54(4), 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul J. J., Singh S. K., Gupta K., Bryant K., Verma R. (2010). Alcohol and HIV in India: A review of current research and intervention. AIDS and Behavior, 14(Suppl 1), S1–S7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9740-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen G., Östlin P. (2007). Unequal, unfair, ineffective and inefficient: Gender inequity in health: Why it exists and how we can change it. Final report of the Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Bangalore and Stockholm: Indian Institute of Management Bangalore and Karolinska Institutet. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley S. (2008). Interpersonal violence in alcohol complicated marital relationships (a study from India). Journal of Family Violence, 23, 767–776. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner D. L., Norman G. R. (2008). Health measurement scales a practical guide to their development and use. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2016). AUDIT-C frequently asked questions. Retrieved April 22, 2016, from http://www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/alcohol-misuse/alcohol-faqs.cfm#1

- Verma R. K., Pulerwitz J., Mahendra V., Khandekar S., Barker G., Fulpagare P., Singh S. K. (2006). Challenging and changing gender attitudes among young men in Mumbai, India. Reproductive Health Matters, 14(28), 135–143. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28261-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R., Pulerwitz J., Mahendra V., Khandekar S., Singh A., Das S., … Barker G. (2008). Promoting gender equity as a strategy to reduce HIV risk and gender-based violence among young men in India: Horizons final report. Washington, DC: Population Council. [Google Scholar]

- Verma R., Schensul S. (2004). Male sexual health problems in Mumbai: Cultural constructs that present opportunities for HIV/AIDS risk education. In Verma Ravi K., Pelto Pertti J., Schensul Stephen L., Joshi Archana. (Eds.), Sexuality in the time of AIDS in India. New Delhi: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson I. M., Graham K., Taft A. (2014). Alcohol interventions, alcohol policy and intimate partner violence: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 14, 881. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2001). Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2005). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yore J., Dasgupta A., Ghule M., Battala M., Nair S., Silverman J., … Raj A. (2016). CHARM, a gender equity and family planning intervention for men and couples in rural India: Protocol for the cluster randomized controlled trial evaluation. Reproductive Health, 13(1), 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]