Abstract

Females are more likely than males to participate in evidence-based health promotion and disease prevention programs targeted for middle-aged and older adults. Despite the availability and benefits of Stanford’s Chronic Disease Self-Management Education (CDSME) programs, male participation remains low. This study identifies personal characteristics of males who attended CDSME program workshops and identifies factors associated with successful intervention completion. Data were analyzed from 45,375 male CDSME program participants nationwide. Logistic regression was performed to examine factors associated with workshop attendance. Males who were aged 65–79 (OR = 1.27, p < .001), Hispanic (OR = 1.22, p < .001), African American (OR = 1.13, p < .001), Asian/Pacific Islander (OR = 1.26, p < .001), Native Hawaiian (OR = 3.14, p < .001), and residing in nonmetro areas (OR = 1.26, p < .001) were more likely to complete the intervention. Participants with 3+ chronic conditions were less likely to complete the intervention (OR = 0.87, p < .001). Compared to health-care organization participants, participants who attended workshops at senior centers (OR = 1.38, p < .001), community/multipurpose facilities (OR = 1.21, p < .001), and faith-based organizations (OR = 1.37, p < .001) were more likely to complete the intervention. Men who participated in workshops with more men were more likely to complete the intervention (OR = 2.14, p < .001). Once enrolled, a large proportion of males obtained an adequate intervention dose. Findings highlight potential strategies to retain men in CDSME programs, which include diversifying workshop locations, incorporating Session Zero before CDSME workshops, and using alternative delivery modalities (e.g., online).

Keywords: men, chronic disease, retention, health promotion, evidence-based programs

Evidence-based health promotion programs for older adults are evaluated interventions that provide expected positive health outcomes to participants, such as improved health and well-being or reduced disease, disability, and injury (National Council on Aging, 2017; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). Several programs have been identified to promote healthy aging, including Stanford’s Chronic Disease Self-Management Education (CDSME) programs (Lorig et al., 1999; Ory, Ahn, Jiang, Smith et al., 2014), A Matter of Balance for fall prevention (Healy et al., 2008), and Healthy IDEAS for depression management, to name a few (Casado et al., 2008; Quijano et al., 2007). The U.S. Administration on Aging (AOA) administers the Older Americans Act, which provides funding specifically for evidence-based programs for older adults (Boutaugh et al., 2014). The AOA also provides grants to support the dissemination of these programs (Boutaugh et al., 2014).

CDSME programs are a suite of low-cost evidence-based programs currently offered in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and 28 other countries around the world (Stanford Patient Education Resource Center, 2017). The flagship intervention, Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP), is a universal program that applies to any chronic condition; however, disease-specific translations exist to build skills to manage arthritis, diabetes, chronic pain, and HIV/AIDS (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Generally, CDSME programs are comprised of six peer-led sessions offered once a week for six consecutive weeks, with each session lasting 2.5 hr (Lorig, Holman, & Sobel, 2006). Each workshop is led by two facilitators, where one facilitator is required to be a nonhealth professional with a chronic disease. The program is ideal for groups of 10 to 15 participants, with a maximum of 20 participants (Stanford Patient Education Research Center, 2012). It has been implemented in a variety of community settings targeting the aging population including senior centers, health-care organizations, and residential facilities (Smith et al., 2014). As per several program evaluations, participating in the program workshops can improve health behaviors, self-rated health, and self-efficacy; reduce disability, fatigue, and distress; and decrease health-care utilization and costs (Lorig et al., 2001; Lorig, Sobel, Ritter, Laurent, & Hobbs, 2000).

Despite the well-known and published benefits of various evidence-based programs, middle-aged and older men are still less likely to engage and complete these programs compared to middle-aged and older women (Anderson, Seff, Batra, Bhatt, & Palmer, 2016; Batra, Page, Melchior, Seff, Vieira, & Palmer, 2013; Ory et al., 2015). Potential explanations include men not perceiving they need the programs (Batra et al., 2013) and the programs not appealing to men or to the senior male culture (Anderson et al., 2016). In the case of CDSME programs, low male enrollment and retention mean older men are missing the opportunity to develop the necessary skills to manage their chronic conditions effectively. While women are more likely than men to experience one or more chronic conditions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015), men have a shorter life expectancy (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a). Therefore, CDSME programs are relevant and beneficial for aging men and women.

Additional research is needed to better understand and increase older male engagement and retention in CDSME programs. The aims of this study were to (a) identify personal and delivery site characteristics of males who attended CDSME program workshops; and (b) examine personal and delivery site characteristics associated with successful intervention completion (i.e., defined as attending at least 4 of the 6 workshop sessions).

Method

Participants and Data Collection

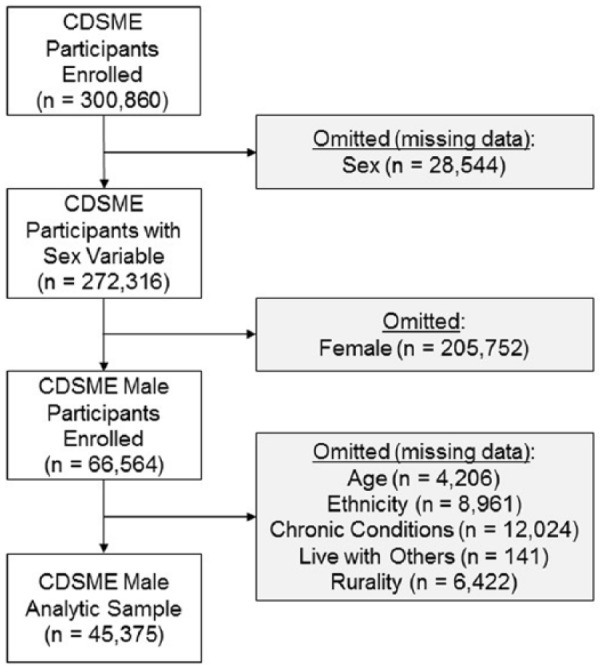

Data were obtained from a nationwide delivery of CDSME programs initially supported by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) Communities Putting Prevention to Work: Chronic Disease Self-Management Program initiative (Boutaugh et al., 2014). At the time of data collection, the AOA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services assisted in disseminating CDSME programs in 45 states, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Ongoing AOA federal funding allowed all participants to take part in the workshops free-of-charge. For this study, data were analyzed from 300,860 participants that enrolled in the CDSME workshops from December 2009 to December 2016 (Smith, Towne et al., 2017). Cases with complete data were used to document the characteristics of males who participated in CDSME workshops nationwide. As such, missing data were omitted and no imputation methods were performed. Based on the aims of this study, cases were initially omitted for missing data on sex (n = 28,544) and those who were female (n = 205,752). Of the remaining 66,564 male participants, additional cases were omitted for missing data on age (n = 4,206), ethnicity (n = 8,961), chronic conditions (n = 12,024), living situation (n = 141), and residential rurality (n = 6,422). Because some cases had missing data for more than one of these variables, the final analytic sample for this study was 45,375 male participants. Figure 1 reports the participant flow diagram for study analyses.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram for study analyses.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to engaging in the intervention. Participation in this study was voluntary, and participant anonymity was preserved for all analyses. Data for this secondary analysis were obtained from a national repository of CDSME Program administrative and self-reported data. The rationale for selecting measures, developing instruments, and establishing data management protocols and procedures are explained in detail elsewhere (Kulinski, Boutaugh, Smith, Ory, & Lorig, 2015). Administrative data included information about the delivery site (e.g., name, type, location) and participant workshop attendance. Self-reported data from the participants were collected using paper–pencil at baseline, which included items related to the participants’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, chronic condition diagnoses, and living situation. Data were only collected from participants at baseline. The baseline instrument took participants approximately 5 min to complete (Kulinski et al., 2015; Smith, Towne et al., 2017). No lifestyle- or behavior-related items were obtained for this grand-scale national roll-out. Rather, because the effectiveness of this program is well documented, data collection focused on monitoring participant reach, intervention dose, and workshop fidelity. Institutional Review Board approval was granted from The University of Georgia (#00000249) for this secondary, de-identified data analysis.

Measures

Dependent variable

Participants’ attendance was identified as the dependent variable in the study. At each workshop, each participant’s attendance was recorded (i.e., continuously from 0 to 6 sessions). As defined by the program developers (Stanford Patient Education Research Center, 2012) and used in previous national studies (Ory, Ahn, Jiang, Lorig et al., 2013; Ory, Smith et al., 2014), participants were determined to have “successfully completed” the workshop if they attended four or more of the six sessions offered (i.e., treated dichotomously). Because CDSME programs are process-based interventions and not content-driven (i.e., focusing on problem solving, action planning, and goal setting), attending more than half of the intervention was theorized to give participants sufficient time to build self-efficacy through trial-and-error and social support (Stanford Patient Education Research Center, 2012). For this reason, the total number of workshop sessions attended was used to indicate “successful completion” rather than which of the specific sessions were attended.

Delivery site and workshop characteristics

The type of delivery site that offered each workshop was recorded. Possible delivery site types included senior centers or Area Agencies on Aging (AAA), residential facilities, health-care organizations, community or multipurpose centers, faith-based organizations, educational institutions, county health departments, tribal centers, workplaces, and other delivery site types. Other delivery site types included organizations such as correctional facilities, heritage clubs, civic associations, and apartment complexes, but were of insufficient size to be separately included in analyses (and were condensed into a single “other” category). For each workshop, the number of participants enrolled was recorded (i.e., continuous, ranging from 1 to 20 participants). As a point of reference, the program developers defined the ideal class size as between 10 and 15 participants in the CDSMP fidelity manual (Stanford Patient Education Research Center, 2012). From the total number of workshop enrollees, the proportion of male participants per workshop was calculated (i.e., continuous in decimal form ranging from .00 [0%] to 1.00 [100%]).

Personal and environmental characteristics

Personal characteristics of the participants included their age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Participants were asked to report whether they lived with others or lived alone. Participants were also asked to self-report all chronic conditions diagnosed by a health professional. Chronic conditions listed included arthritis, cancer, depression, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, lung disease, stroke, and other chronic conditions. The number of self-reported chronic conditions was then trichotomized for analyses (i.e., 1 chronic condition, 2 chronic conditions, 3+ chronic conditions). Participants reported the ZIP Code in which they resided, which enabled researchers to categorize each residence as metro or nonmetro based on the rural–urban commuting area codes (U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2014). Using their ZIP Code of residence, the proportion of families living in the participants’ ZIP Code who fell below the 200% poverty line was retrieved.

Analyses

All analyses in this study were performed using SPSS version 24. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all male participants and bifurcated based on successfully completing the workshop. Chi-square (χ2) tests were used to identify distribution differences across categories for categorical variables. Independent sample t-tests were used to identify mean differences across categories for continuous variables. A binary logistic regression model was fitted for male participants to identify factors associated with successful workshop completion. Odds ratios, confidence intervals, and p-values were reported. Because of the large sample size (and in an attempt to reduce Type I error), only relationships with p-values equal to or less than .001 were reported as statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 reports male CDSME participant characteristics. A total of 45,375 male participants enrolled in the workshops. The majority of participants were between the ages of 65 and 79 years (40.7%; n = 18,449), non-Hispanic (85.2%; n = 38,663), and white (63.7%; n = 28,901). Most participants lived with others (61.4%; n = 27,845), resided in metro areas (82.3%; n = 37,353), and reported being diagnosed with three or more chronic conditions (39.0%; n = 17,702). Delivery sites serving the most participants included health-care organizations (27.6%; n = 12,538), senior centers/AAAs (21.7%; n = 9,860), residential facilities (15.1%; n = 6,861), community/multipurpose facilities (11.5%; n = 5,227), and faith-based organizations (7.3%; n = 3,291). The average number of participants enrolled in each workshop was 13.56 (±6.71) with approximately 41% (±23%) being male participants. Overall, 74.5% of male participants successfully completed the workshops.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Completion Rate.

| Successful workshop

completion |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 45,375) | No (n = 11,584) | Yes (n = 33,791) | χ2 or t | p | |

| Age | 70.63 | <.001 | |||

| Under 50 years | 15.5% (7,016) | 15.0% (1,734) | 15.6% (5,282) | ||

| 50–64 years | 28.9% (13,134) | 29.6% (3,426) | 28.7% (9,708) | ||

| 65–79 years | 40.7% (18,449) | 38.4% (4,449) | 41.4% (14,000) | ||

| 80+ years | 14.9% (6,776) | 17.0% (1,975) | 14.2% (4,801) | ||

| Ethnicity | 6.27 | .012 | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 85.2% (38,663) | 85.9% (9,953) | 85.0% (27,810) | ||

| Hispanic | 14.8% (6,712) | 14.1% (1,631) | 15.0% (5,081) | ||

| Race | 100.02 | <.001 | |||

| White | 63.7% (28,901) | 65.8% (7,626) | 63.0% (21,275) | ||

| African American | 18.1% (8,198) | 17.7% (2,052) | 18.2% (6,146) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3.6% (1,623) | 3.2% (367) | 3.7% (1,256) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.9% (865) | 1.9% (222) | 1.9% (643) | ||

| Native Hawaiian | 1.2% (546) | 0.4% (51) | 1.5% (495) | ||

| Other/multiple races | 11.6% (5,242) | 10.9% (1,266) | 11.8% (3,976) | ||

| Living situation | 0.00 | .988 | |||

| Lives alone | 38.6% (17,530) | 38.6% (4,476) | 38.6% (1,354) | ||

| Lives with others | 61.4% (27,845) | 61.4% (7,108) | 61.4% (20,737) | ||

| Number of chronic conditions | 40.22 | <.001 | |||

| 1 condition | 31.2% (14,179) | 29.0% (3,360) | 32.0% (10,819) | ||

| 2 condition | 29.7% (13,494) | 30.1% (3,483) | 29.6% (10,011) | ||

| 3+ condition | 39.0% (17,702) | 40.9% (4,741) | 38.4% (12,961) | ||

| Rurality of participant residence | 82.57 | <.001 | |||

| Metro | 82.3% (37,353) | 85.1% (9,858) | 81.4% (27,495) | ||

| Nonmetro | 17.7% (8,002) | 14.9% (1,726) | 18.6% (6,296) | ||

| Percent of families below 200% poverty | 19.59 (±7.76) | 19.63 (±7.66) | 19.57 (±7.79) | 0.75 | .455 |

| Delivery site type | 187.53 | <.001 | |||

| Health-care organizations | 27.6% (12,538) | 29.3% (3,389) | 27.1% (9,149) | ||

| Senior center/AAA | 21.7% (9,860) | 18.9% (2,184) | 22.7% (7,676) | ||

| Residential facilities | 15.1% (6,861) | 16.3% (1,888) | 14.7% (4,973) | ||

| Community/multipurpose facilities | 11.5% (5,227) | 10.7% (1,245) | 11.8% (3,982) | ||

| Faith-based organizations | 7.3% (3,291) | 6.2% (723) | 7.6% (2,568) | ||

| Educational institutions | 1.6% (707) | 1.4% (162) | 1.6% (545) | ||

| County health departments | 1.3% (607) | 1.4% (160) | 1.3% (447) | ||

| Workplaces | 0.8% (355) | 0.6% (66) | 0.9% (289) | ||

| Tribal organizations | 0.3% (139) | 0.4% (45) | 0.3% (94) | ||

| Other | 12.8% (5,790) | 14.9% (1,722) | 12.0% (4,068) | ||

| Number of participants enrolled in workshop | 13.56 (±6.71) | 15.51 (±10.23) | 12.89 (±4.77) | 26.64 | <.001 |

| Percent of men enrolled in workshop | 0.41 (±0.23) | 0.38 (±0.20) | 0.42 (±0.24) | −15.27 | <.001 |

Note. AAA = Area Agencies on Aging.

When comparing male CDSME participant characteristics by successful workshop completion, a larger proportion of males aged 65–79 years and smaller proportion of males 80+ years successfully completed the workshops (χ2 = 70.63, p < .001). A smaller proportion of white participants and larger proportion of Native Hawaiian participants successfully completed the workshops (χ2 = 100.02, p < .001). Larger proportions of male participants who attended CDSME in senior centers/AAA, community/multipurpose facilities, and faith-based organizations successfully completed the workshops (χ2 = 187.53, p < .001). On average, males in smaller workshops successfully completed a workshop (t = 26.64, p < .001). On average, a larger percentage of males who attended workshops with larger proportions of males successfully completed a workshop (t = −15.27, p < .001).

Table 2 presents results of the binary logistic regression identifying factors associated with successful workshop completion among male participants. Males between the ages of 65 to 79 (OR = 1.27, p < .001) and those who resided in nonmetro areas (OR = 1.26, p < .001) were more likely to complete a workshop. Males who were Hispanic (OR = 1.22, p < .001), African American (OR = 1.13, p < .001), Asian/Pacific Islander (OR = 1.26, p < .001), and Native Hawaiian (OR = 3.14, p < .001) were more likely to complete a workshop. Participants with two (OR = 0.91, p = .001) or three or more (OR = 0.87, p < .001) chronic conditions were less likely to complete a workshop. Relative to those who attended workshops held at health-care organizations, males who participated in workshops held at senior centers/AAA (OR = 1.38, p < .001), community/multipurpose facilities (OR = 1.21, p < .001), faith-based organizations (OR = 1.37, p < .001), educational institutions (OR = 1.36, p = .001), and tribal organizations (OR = 1.57, p = .001) were more likely to successfully complete a workshop. Men who participated in workshops with more participants were less likely to successfully complete the workshop (OR = 0.95, p < .001). Men who participated in workshops with a larger proportion of men were more likely to successfully complete the workshop (OR = 2.14, p < .001).

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Successful Workshop Completion among Male Participants (n = 45,375).

| SE | 95% CI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | OR | p | Lower | Upper | ||

| Age: Under 50 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Age: 50–64 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 1.08 | .034 | 1.01 | 1.16 |

| Age: 65–79 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 1.27 | <.001 | 1.18 | 1.36 |

| Age: 80+ | 0.09 | 0.04 | 1.09 | .046 | 1.00 | 1.19 |

| Non-Hispanic | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Hispanic | 0.20 | 0.04 | 1.22 | <.001 | 1.13 | 1.32 |

| White | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| African American | 0.13 | 0.03 | 1.13 | <.001 | 1.07 | 1.21 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.23 | 0.06 | 1.26 | <.001 | 1.11 | 1.42 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.00 | 0.09 | 1.00 | .983 | 0.85 | 1.19 |

| Native Hawaiian | 1.14 | 0.15 | 3.14 | <.001 | 2.34 | 4.21 |

| Other/multiple races | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.05 | .282 | 0.96 | 1.14 |

| Lives alone | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Lives with others | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.96 | .100 | 0.92 | 1.01 |

| 1 condition | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| 2 condition | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.91 | .001 | 0.86 | 0.96 |

| 3+ condition | −0.14 | 0.03 | 0.87 | <.001 | 0.82 | 0.91 |

| Participant residence: Metro | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Participant residence: Nonmetro | 0.23 | 0.03 | 1.26 | <.001 | 1.18 | 1.34 |

| Percent of families below 200% poverty | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | .027 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| Delivery site: Health-care organizations | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Delivery site: Senior center/AAA | 0.32 | 0.03 | 1.38 | <.001 | 1.29 | 1.47 |

| Delivery site: Residential facilities | 0.02 | 0.04 | 1.02 | .569 | 0.95 | 1.09 |

| Delivery site: Community/multipurpose facilities | 0.19 | 0.04 | 1.21 | <.001 | 1.12 | 1.31 |

| Delivery site: Faith-based organizations | 0.32 | 0.05 | 1.37 | <.001 | 1.25 | 1.51 |

| Delivery site: Educational institutions | 0.31 | 0.09 | 1.36 | .001 | 1.14 | 1.64 |

| Delivery site: County health departments | 0.01 | 0.10 | 1.01 | .933 | 0.84 | 1.22 |

| Delivery site: Tribal organizations | 0.45 | 0.14 | 1.57 | .001 | 1.19 | 2.06 |

| Delivery site: Workplaces | −0.24 | 0.20 | 0.79 | .217 | 0.54 | 1.15 |

| Delivery site: Other | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.07 | .091 | 0.99 | 1.16 |

| Number of participants enrolled in workshop | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.95 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Percent of men enrolled in workshop | 0.76 | 0.06 | 2.14 | <.001 | 1.92 | 2.39 |

Note. Referent group = nonsuccessful workshop completion (attending less than four workshop sessions). AAA = Area Agencies on Aging.

Discussion

This study examined characteristics of CDSME program participants and focused on factors associated with male workshop completion. Although three in four male participants successfully completed the workshops, there were differences between those who simply enrolled and those who were retained until program completion. Participant characteristics including being 65 to 79 years old, a minority, living in nonmetro areas, and having less chronic conditions resulted in greater program completion. Several reasons may help explain why males with those characteristics were more likely to complete the program. As of age 65, males typically have more health screenings (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2017) and if diagnosed with a chronic condition may be more open to the need to complete such evidence-based programs to gain the knowledge and skills to effectively manage their condition (Sandlund et al., 2017). Older men are also more likely to live with others such as a spouse (Administration on Aging, 2014) and can rely on them for motivation to start and finish the program (Clark et al., 2013).

Men from minority populations generally experience more severe or greater chronic conditions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017b). They often receive poorer quality care and face increased barriers in seeking care for chronic disease management (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017b). Minority men may therefore be more likely to complete the workshops as it removes some of the barriers they face in accessing care. For example, a study by Alegría, Alvarez, Ishikawa, DiMarzio, and McPeck (2016) found that Hispanics prefer to handle a problem on their own. Participating in the CDSME program allows them to develop their self-efficacy, which would help them be successful in managing their condition on their own after a few workshops (Stanford Patient Education Research Center, 2012). Another potential barrier they may face is a lack of cultural competency (Alegría et al., 2016). Considering that one of the two workshop facilitators is a nonprofessional with a chronic disease, it is possible that this facilitator shares the same race, ethnicity, and/or cultural background as some of the participants, hence contributing to program retention.

Males in nonmetro areas, on the other hand, may recognize the value of these evidence-based programs, which may not be commonly accessible in their area. It is known that clinical care may be limited or hard to access in nonmetro areas (Chan, Hart, & Goodman, 2006; Rural Health Information Hub, 2017). Finally, compared to males with more chronic conditions, males with less chronic conditions may have less doctors’ visits and other barriers related to their illness (e.g., fatigue or pain) that would prevent them from completing the program (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2012; Hudon et al., 2016).

Findings also suggested that the program context, including the group composition and the delivery site, also impacted participant retention. Similar to other research findings (Anderson et al., 2016; Hudon et al., 2016), maintaining session participation to fewer rather than more participants (i.e., smaller groups) and having a higher proportion of men in the group (i.e., limiting group heterogeneity) can help retain male participants. Small groups may make the workshop more interactive and personalized, which may contribute to increasing its perceived relevance and value to program participants inciting them to attend a greater number of sessions. Due to male gender roles, having a group with more males may help participants be more comfortable to engage in health-related discussions with their peers (Anderson et al., 2016).

Offering the program outside a health-care facility may also contribute to participant retention. Previous studies have indicated that interventions may be easier to disseminate in settings frequently visited by older adults (Ory, Liles, & Lawler, 2009; Ory et al., 2010). Farone, Fitzpatrick, and Tran (2005) also suggested that attendees at senior centers experience lower levels of psychological distress under stressful life situations (e.g., managing a chronic disease) compared to non-attendees, which may allude to a more supportive environment for program participants (Turner, 2004), compared to health-care–related delivery sites.

Strategies are needed to retain the one third of participants not currently completing the CDSME program. The rest of the program participants may face other challenges and barriers that prevent them from regularly attending the program workshop sessions, including scheduling conflicts due to employment and family responsibilities (Hudon et al., 2016; National Council on Aging, 2016), duration of the program (Administration on Aging, 2013), and content barriers such as personal relevance and need (Anderson et al., 2016; Hudon et al., 2016; Sandlund et al., 2017). One solution to address some of these barriers and ensure that the content of the program is relevant to the participants is to offer them Session Zero. Session Zero is an optional orientation session prior to the beginning of the program that serves to inform potential participants of the program, its purpose, content, and required time commitment, invite participants to ask questions, and evaluate their readiness to fully engage in the intervention (National Council on Aging, 2016). In a previous study by Jiang et al. (2015), Session Zero was taken by 21% of participants, and those who had taken it had significantly higher odds of completing the workshops. In a sensitivity analysis among male participants in the current study (data not reported), 17.8% (n = 6,016) of participants attended workshops with a Session Zero (of 33,784 cases where Session Zero information was available), and the odds of successful completion were higher among males attending these workshops (OR = 1.17, p < .001). Due to its reported potential to increase participant retention (Jiang et al., 2015), Session Zero should be considered as a mandatory component for future implementations of this program, pending time and resource constraints.

Another solution is to offer all participants the opportunity to enroll either in the in-person CDSME workshops or the internet-based CDSME program. A few researchers (Jaglal et al., 2013; Lorig, Ritter, Laurent, & Plant, 2006) have tested the use of telehealth to offer this program and reported successful reach and retention of program participants.

This study has limitations. There were substantial cases with missing data, which resulted in their omission from study analyses. Missing data may have occurred because this national roll-out relied on grantees (and their infrastructure of workshop leaders) to collect data from participants and enter it into the national data repository. Further investigation is needed to better understand the missing data for this initiative, and whether rates of missingness improved or worsened over time. While statistical imputation was not used in this study, it could be considered for future analyses. Specific measures, such as participants’ education level, marital status, and health literacy skills, were not available for this study and may have helped to provide a greater overview of male engagement and retention in this national CDSME program dissemination. Statistical significance should be interpreted with moderate caution because the large sample size for this study may have resulted in Type I errors.

Despite these limitations, study findings revealed that once enrolled, males are generally willing to participate in CDSME workshops and complete the full evidence-based program. Continuous efforts can be made to improve how and where the program is offered to increase retention of the underrepresented sex.

Acknowledgments

The Administration for Community Living/Administration on Aging is the primary funding source for this national study. The findings, conclusions, and opinions expressed do not necessarily represent official Administration for Community Living/Administration on Aging policy. The National Council on Aging served as the Technical Assistance Resource Center for this initiative and collected data on program participation from grantees. We also recognize the original support from the Administration on Aging with assistance from the National Council on Aging for the CDSME National Database management under cooperative agreement number 90CS0058-01.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Administration on Aging. (2013). Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) process evaluation. Retrieved from https://aoa.acl.gov/Program_Results/docs/CDSMPProcessEvaluationReportFINAL062713.pdf

- Administration on Aging. (2014). A profile of older Americans: 2014. Retrieved from https://aoa.acl.gov/aging_statistics/profile/2014/docs/2014-profile.pdf

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2012). AHRQ CDSMP evaluation design—Appendix D: Site interview summary. Retrieved from https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/final-reports/aoa/aoachronic-apd.pdf

- Alegría M., Alvarez K., Ishikawa R. Z., DiMarzio K., McPeck S. (2016). Removing obstacles to eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in behavioral health care. Health Affairs, 35(6), 991–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C., Seff L. R., Batra A., Bhatt C., Palmer R. C. (2016). Recruiting and engaging older men in evidence-based health promotion programs: Perspectives on barriers and strategies. Journal of Aging Research, 2016, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra A., Page T., Melchior M., Seff L., Vieira E. R., Palmer R. C. (2013). Factors associated with the completion of falls prevention program. Health Education Research, 28(6), 1067–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutaugh M. L., Jenkins S. M., Kulinski K. P., Lorig K. R., Ory M. G., Smith M. L. (2014). Closing the disparity gap: The work of the administration on aging. Generations, 38(4), 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Casado B. L., Quijano L. M., Stanley M. A., Cully J. A., Steinberg E. H., Wilson N. L. (2008). Healthy IDEAS: Implementation of a depression program through community-based case management. The Gerontologist, 48(6), 828–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Percent of U.S. adults 55 and over with chronic conditions. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Self-management education. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/interventions/self_manage.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017. a). Older persons’ health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017. b). Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/reach.htm

- Chan L., Hart L. G., Goodman D. C. (2006). Geographic access to health care for rural medicare beneficiaries. The Journal of Rural Health, 22(2), 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L., Thoreson S., Goss C. W., Zimmer L. M., Marosits M., DiGuiseppi C. (2013). Understanding fall meaning and context in marketing balance classes to older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 32(1), 96–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farone D. W., Fitzpatrick T. R., Tran T. V. (2005). Use of senior centers as a moderator of stress-related distress among Latino elders. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 46(1), 65–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy T. C., Peng C., Haynes M. S., McMahon E. M., Botler J. L., Gross L. (2008). The feasibility and effectiveness of translating a matter of balance into a volunteer lay leader model. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27(1), 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hudon C., Chouinard M.-C., Diadiou F., Bouliane D., Lambert M., Hudon É. (2016). The chronic disease self-management program: The experience of frequent users of health care services and peer leaders. Family Practice, 33(2), 167–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglal S. B., Haroun V. A., Salbach N. M., Hawker G., Voth J., Lou W., … Bereket T. (2013). Increasing access to chronic disease self-management programs in rural and remote communities using telehealth. Telemedicine and e-Health, 19(6), 467–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Smith M. L., Chen S., Ahn S., Kulinski K. P., Lorig K., Ory M. G. (2015). The role of session zero in successful completion of chronic disease self-management program workshops. Frontiers in Public Health, 2(205), 95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulinski K. P., Boutaugh M. L., Smith M. L., Ory M. G., Lorig K. (2015). Setting the stage: Measure selection, coordination, and data collection for a national self-management initiative. Frontiers in Public Health, 2(206). doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K., Holman H., Sobel D. (2006). Living a healthy life with chronic conditions: Self-management of heart disease, fatigue, arthritis, worry, diabetes, frustration, asthma, pain, emphysema, and others. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K., Ritter P., Laurent D., Plant K. (2006). Internet-based chronic disease self-management: A randomized trial. Medical Care, 44(11), 964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K. R., Ritter P., Stewart A. L., Sobel D. S., Brown B. W., Jr., Bandura A., … Holman H. R. (2001). Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Medical Care, 39(11), 1217–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K. R., Sobel D. S., Ritter P. L., Laurent D., Hobbs M. (2000). Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Effective Clinical Practice, 4(6), 256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K. R., Sobel D. S., Stewart A. L., Brown B. W., Jr., Bandura A., Ritter P., … Holman H. R. (1999). Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: A randomized trial. Medical Care, 37(1), 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Aging. (2016). Tip sheet: Increasing completion of Chronic Disease Self-Management Education (CDSME) workshops. Retrieved from http://www.qtacny.org/wp-content/uploads/2016-Completer-Rate-Tip-Sheet-FINAL-1.pdf.pdf

- National Council on Aging. (2017). About evidence-based programs. Retrieved from https://www.ncoa.org/center-for-healthy-aging/basics-of-evidence-based-programs/about-evidence-based-programs/

- Ory M. G., Ahn S., Jiang L., Lorig K., Ritter P., Laurent D. D., … Smith M. L. (2013). National study of chronic disease self-management six-month outcome findings. Journal of Aging and Health, 25(7), 1258–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory M. G., Ahn S., Jiang L., Smith M. L., Ritter P. L., Whitelaw N., Lorig K. (2013). Successes of a national study of the chronic disease self-management program: Meeting the triple aim of health care reform. Medical Care, 51(11), 992–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory M. G., Liles C., Lawler K. (2009). Building healthy communities for active aging: A national recognition program. Generations, 33(4), 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ory M. G., Smith M. L., Parker E. M., Jiang L., Chen S., Wilson A. D., … Lee R. (2015). Fall prevention in community settings: Results from implementing Tai Chi: Moving for better balance in three states. Frontiers in Public Health, 2, 216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory M. G., Smith M. L., Patton K., Lorig K., Zenker W., Whitelaw N. (2013). Self-management at the tipping point: Reaching 100,000 Americans with evidence-based programs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(5), 821–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory M. G., Smith M. L., Wade A., Mounce C., Wilson A., Parrish R. (2010). Implementing and disseminating an evidence-based program to prevent falls in older adults, Texas, 2007–2009. Preventing Chronic Disease, 7(6), A130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quijano L. M., Stanley M. A., Petersen N. J., Casado B. L., Steinberg E. H., Cully J. A., Wilson N. L. (2007). Healthy IDEAS: A depression intervention delivered by community-based case managers serving older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 26(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rural Health Information Hub. (2017). Barriers to health promotion and disease prevention in rural areas. Retrieved from https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/community-health/health-promotion/1/barriers

- Sandlund M., Skelton D. A., Pohl P., Ahlgren C., Melander-Wikman A., Lundin-Olsson L. (2017). Gender perspectives on views and preferences of older people on exercise to prevent falls: A systematic mixed studies review. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. L., Ory M. G., Ahn S., Kulinski K. P., Jiang L., Horel S., Lorig K. (2014). National dissemination of chronic disease self-management education programs: An incremental examination of delivery characteristics. Frontiers in Public Health, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. L., Towne S. D., Jr., Herrera-Venson A., Cameron K., Kulinski K. P., Lorig K., … Ory M. G. (2017). Dissemination of Chronic Disease Self-Management Education (CDSME) programs in the United States: Intervention delivery by rurality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), E638. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford Patient Education Research Center. (2012). Program fidelity manual: Stanford self-management programs 2012 update. Stanford, CA: Stanford School of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford Patient Education Resource Center. (2017). Organizations licensed to offer the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP). Retrieved from http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/organ/cdsites.html

- Turner K. W. (2004). Senior citizens centers: What they offer, who participates, and what they gain. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 43(1), 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. (2014). Rural-urban commuting area codes overview. Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx#.U-ObPmPqlZU

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). ARRA—Communities putting prevention to work: Chronic disease self-management program 2012. Retrieved from https://www.cfda.gov/index?s=program&mode=form&tab=step1&id=5469a61f2c5f25cf3984fc3b94051b5f

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Disease prevention and health promotion services (OAA Title IIID). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2017). Health screening: Men age 65 and older. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/007466.htm