Abstract

Maize rough dwarf disease, caused by rice black-streaked dwarf virus (RBSDV), is a devastating disease in maize (Zea mays L.). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are known to play critical roles in regulation of plant growth, development, and adaptation to abiotic and biotic stresses. To elucidate the roles of miRNAs in the regulation of maize in response to RBSDV, we employed high-throughput sequencing technology to analyze the miRNAome and transcriptome following RBSDV infection. A total of 76 known miRNAs, 226 potential novel miRNAs and 351 target genes were identified. Our dataset showed that the expression patterns of 81 miRNAs changed dramatically in response to RBSDV infection. Transcriptome analysis showed that 453 genes were differentially expressed after RBSDV infection. GO, COG and KEGG analysis results demonstrated that genes involved with photosynthesis and metabolism were significantly enriched. In addition, twelve miRNA-mRNA interaction pairs were identified, and six of them were likely to play significant roles in maize response to RBSDV. This study provided valuable information for understanding the molecular mechanism of maize disease resistance, and could be useful in method development to protect maize against RBSDV.

Introduction

Maize is one of the most important and widely distributed crops in the world, providing more than a billion tons of human food and animal feed every year (FAO, http://faostat.fao.org/). However, maize production is threaten by a number of diseases, including maize rough dwarf disease (MRDD). MRDD is a devastating disease for maize, resulting in severe growth abnormalities, such as plant dwarfing, dark green leaf and a vein clearing. In China, the pathogen of MRDD is Rice black-streaked dwarf virus (RBSDV), a Fijivirus in the family of Reoviridae1. Recently, the disastrous losses caused by RBSDV have already spread into most maize growing districts of China2. Although some maize germplasm displayed low level of resistance to RBSDV, the high resistant varieties were rare. The control of MRDD mainly depends on cultivation management to avoid small brown plant hoppers (BPHs; Laodelphax striatellus), which transmitted the virus to maize and rice. BPHs are a class of long-distance migratory pest and difficult to control. Therefore, improving maize resistance to RBSDV and planting resistant cultivars are of great necessity. To increasing the resistance of maize, understanding the molecular mechanism of RBSDV pathogenesis is highly required.

During the long history of evolution, plants have evolved a series of flexible defense responses to resist the invasion of pathogenic microorganisms. Hypersensitive response (HR) and systemic acquired resistance (SAR) were two important responses, which usually happened in infection local tissues and uninfected tissues, respectively3. In the defense responses, a large number of genes, such as the defense-related genes, pathogenesis-related (PR)-protein genes could be induced. For example, the expression of PR-1, PR-2 and PR-5 were induced for increased resistance against Pernospore parasitica and Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis4,5. Other genes, such as p450 monooxegenases, hypersensitivity-related genes, cellulases, ABC transporters, receptor-like kinases, serine/threonine kinases, phosphoribosylanthranilate transferases and hypothetical R genes, were induced upon taxonomically distinct tobacco rattle virus (TRV) infection6. Gene expression profile of RBSDV-infected maize was investigated using microarray, and the results demonstrated that the expressions of various resistance-related genes, cell wall and development related genes were altered7. These results provided valuable information to uncover the molecular mechanisms to understand symptom development in rough dwarf-related diseases. Recently, studies demonstrated that pathogen infection not only change the expression of disease resistance genes but also the endogenous miRNAs8–11.

MiRNA, is a member of endogenous and non-coding small RNA with the length of 20–24 nt. MiRNA negatively regulate gene expression via mRNA cleavage or translational inhibition of its targets, exhibiting important roles in regulation of plant growth, development, and adaptation to stresses12–15. Numerous miRNAs have been reported to be induced by pathogen infection and contribute to the gene expression reprogramming in host defense responses. Based on deep sequencing data and RNA-blot assay, a group of known rice miRNAs were differential expressed upon Magnaporthe oryzae infection. Overexpression of miR160a and miR398b enhanced disease resistance in the transgenic rice16. Induction of miRNAs were also observed in wheat and peanut after infected with powdery mildew and bacterial wilt pathogens, respectively9,11. In tomato, a member of NBS-LRR disease resistance (R) gene were proved to be regulated by miR482 and miR211817. Studies revealed that miR472 and RDR-mediated silencing pathway represented a key regulatory checkpoint modulating both PTI (pathogens induce pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity) and ETI (effector-triggered immunity) via post-transcriptional control of R genes18. Based on microarray data, the expression of 14 stress-regulated rice miRNAs was induced by southern rice black-streaked dwarf virus (SRBSDV) infection10.

Up to now, a total of 321 maize miRNA mature and 172 precursors sequences have been deposited in miRBase (www.mirbase.org). Many miRNAs have been confirmed to play regulation roles in maize growth, development and stress response19–22. For example, maize ts4 encodes a member of miR172, controls sex determination and meristem cell fate by targeting Tasselseed6/indeterminate spikelet1, an APETALA2 floral homeotic transcription factor23. Four maize miRNAs, miR811, miR829, miR845 and miR408, were differentially expressed in response to Exserohilum turcicum, a major pathogenic fungus of maize causing northern leaf blight. Over-expression of miR811 and miR829 conferred transgenic lines with high degree of resistance to E. turcicum8. However, there is no report about miRNA response in maize upon RBSDV infection.

In this study, we employed high-throughput sequencing technology to characterize the changes in transcriptome and miRNAome following RBSDV infection. Integrated analysis of gene and miRNA datasets revealed miRNA-mRNA interaction pairs that involved in leaf development, cell wall synthesis and degradation, plant-pathogen interaction. Our results provided valuable information to reveal the molecular mechanisms between the interaction of RBSDV and maize.

Results

Small RNA deep sequencing and data analysis

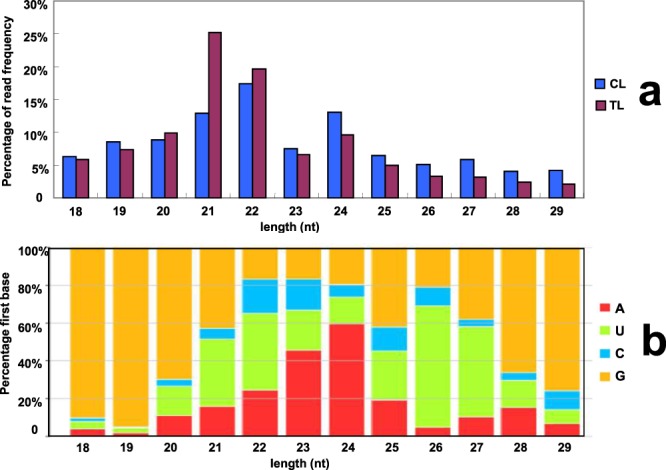

Maize B73 was naturally infected by RBSDV in the field where the Maize Rough Dwarf Disease happened seriously. The control plants were grown in the field and covered by net to prevent the planthoppers, the carrier of the virus. To test whether plants were infected by RBSDV, two pair of primers pS6–604 and pS7–342 were designed according to the genome sequences of segment S6 (GenBank No: HF955010) and segment S7 (GenBank No: HF955011) of RBSDV, respectively. These two pair of primers were used to amplify in the maize individuals with RBSDV symptoms. As a result, the virus genes were amplified in all treatment plants, and could not be detected in control plants (Supplementary Fig. S1). These results suggested that the phenotype/symptoms were caused by RBSDV. To identify small RNAs from maize, two libraries generated using RBSDV infected plants (TL1 and TL2) and two libraries (CL1 and CL2) generated using the control plants were constructed for high-throughput sequencing. A total of 23,056,821, 20,003,963, 26,678,964 and 20,585,338 raw reads were obtained from CL1, CL2, TL1 and TL2, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). After removing low quality reads, reads less than 18 nt and reads longer than 29 nt, a total of 9,274,931, 8,351,418, 9,552,470 and 13,037,763 clean reads remained from CL1, CL2, TL1 and TL2 libraries, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). These clean reads were used for further analysis. Firstly, clean reads were aligned with maize genome (B73 RefGen_V2, release 5b.60) and Rfam database. Reads annotated as rRNA, snRNA (small nuclear RNAs), snoRNA (nucleolar RNAs), repbase (reads positioned at repeat loci) and tRNA were identified (Supplementary Table S2). The distribution of small RNAs identified from CL and TL libraries is summarized (Fig. 1a). It was also shown that 21-nt small RNAs were the predominant class in maize, followed by 22-nt and 24-nt small RNAs. After infected with RBSDV, the number of 20-, 21- and 22-nt small RNAs in TL libraries increased, while the number of other small RNAs decreased compared with CL libraries. The first nucleotide bias of small RNAs was analyzed. For the small RNAs of 20–22 nt, the canonical length of miRNAs, a strong bias for U of the first nucleotide was observed (Fig. 1b). The small RNA sequencing data has been deposited in NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA) database (BioProject ID: PRJNA438075, Accession number: SRR6829172-SRR6829175).

Figure 1.

Statistics of length distribution and first nucleotide bias of small RNA libraries. a: Length distribution of small RNAs identified from CL and TL libraries, b: First nucleotide bias analysis of total small RNAs.

Identification of known and novel miRNAs in maize

Comparison the maize small RNAs to the miRBase allowed us to identify 76 known miRNAs, belonging to 26 miRNA families (Supplementary Table S3). Previous studies found that there were twenty miRNAs families were conserved in Arabidopsis, Oryza ostiva and Populus trichocarpa13,24. In our dataset, nineteen conserved miRNA families were detected in maize. In addition, seven known but non-conserved miRNA families including MIR408, MIR528, MIR529, MIR827, MIR1432, MIR2118 and MIR2275 were also identified. The normalized expression level of miR166f was 103,108 (TP10M, Numbers of tags per ten million), representing the most abundant miRNAs. The abundance of miR395o-5p, miR2118d, miR395k-3p, miR167g-3p, miR167c-3p, miR408b-3p, miR169r-3p, miR2275a-5p, miR398b-3p and miR398a-3p was low in both sRNA libraries (Supplementary Table S3).

According to the criteria as described in previously25, a total of 226 potential novel miRNAs were identified. The length of novel miRNAs ranged from 20 to 22 nt, and more than 93% novel miRNAs with the length of 21–22 nt (Supplementary Table S4). The negative folding free energies of these precursors hairpin structures ranged from −89.8 to −16.1 (kcal/mol) with an average of −44.08 kcal/mol, which is similar to the results from other plants. Some of these novel miRNAs were specifically detected in control or treatment libraries. For example, zma-miRn177 was detected only in control libraries, while zma-miRn223 and zma-miRn224 were observed only in treatment libraries.

Target prediction of maize miRNAs and function annotation

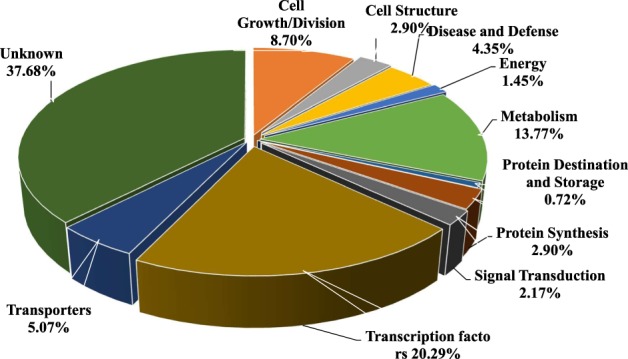

To gain a better understanding of the regulation roles of maize known and novel miRNAs, target genes were predicted using psRNATarget software by comparing miRNA sequences against maize B73 reference genome. A total of 213 targets of 50 known miRNAs and 138 targets of 75 novel miRNA candidates were identified (Supplementary Table S5-S6). Functional annotation of these target genes showed that many defense related genes were regulated by known miRNAs. For example, peroxidase 2 gene (GRMZM2G427815), LRR receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase gene (GRMZM2G304745), and a Zea mays rust resistance protein rp3–1 (GRMZM2G045955) were targeted by zma-miR399a-5p, zma-miR390b-5p and zma-miR528b-5p, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). For the targets of novel miRNAs, 37.68% of them were genes with unknown function and 20% of them were transcription factors. Our data showed that many defense related genes were also regulated by novel miRNAs including a plant viral-response family protein gene (GRMZM2G171036), which was regulated by miRn200 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 2.

Function classification of the target genes of novel miRNAs.

MiRNA expression profiles upon RBSDV infection

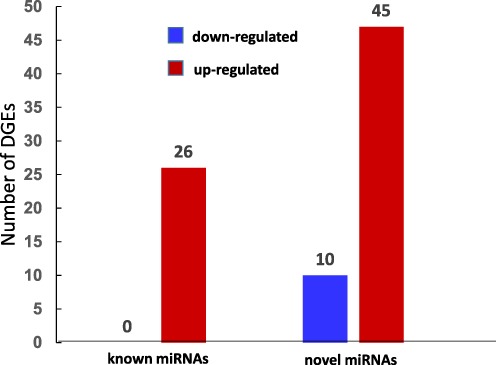

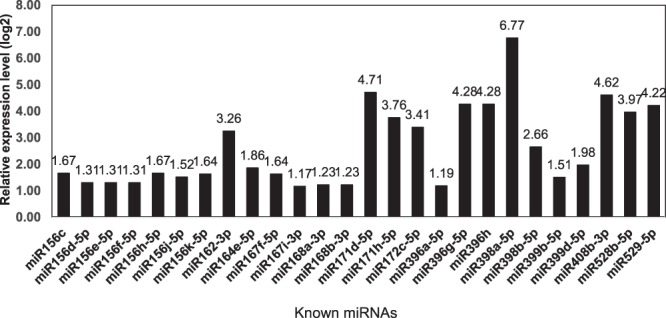

To analyze the expression change of miRNAs in response to RBSDV, the abundance of miRNAs was normalized using numbers of tags per ten million (TP10M), and the relatively expression level of miRNA was calculating by log2Ratio (TL/CL). A total of 81 differentially expressed miRNAs (|log2| ≥ 1.0) were identified, including 26 known miRNAs and 55 novel miRNAs (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the 26 differential expressed known miRNAs were all up-regulated, and the overall expression levels of all known miRNAs showed up-regulation trend in response to RBSDV (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S7). Among the 55 differential expressed novel miRNAs, 45 were up-regulated and 10 were down-regulated (Fig. 3). MiRn177 was expressed only in control samples, miRn223 and miRn224 expressed only in virus treated samples. In addition, our results showed that the expression levels of four novel miRNAs, miRn222, miRn225, miRn226 and miRn146 were significantly increased after infected with RBSDV (Supplementary Fig. S2, Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 3.

Number of different expressed miRNAs in response to RBSDV.

Figure 4.

Different expressed known miRNAs identified in sRNA libraries.

Global mRNA expression profiles in maize in response to virus infection

In order to identify the global gene expression alteration upon virus infection, we used the next generation sequencing technology to analyze the transcriptome of maize before and after virus infection. A total of 8.13 Gb data was generated, comprised of more than 40 million reads (Supplementary Table S8). Sequencing randomness analysis was tested for estimating the gene whether or not random distributed in different positions on each genes. The statistical analysis result showed that the sequencing in all samples was in good randomness (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Saturation analysis showed that the number of genes increased with the total number of tags and reached a plateau after 2.5 million tags (Supplementary Fig. S3b). Using TopHat alignment, more than 89% of the reads could be successfully mapped to B73 genome, which covers 27,554 genes. The RNA-seq data have been deposited at SRA database (BioProject ID: PRJNA438075, Accession number: SRR6829168-SRR6829171).

Identification and function analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

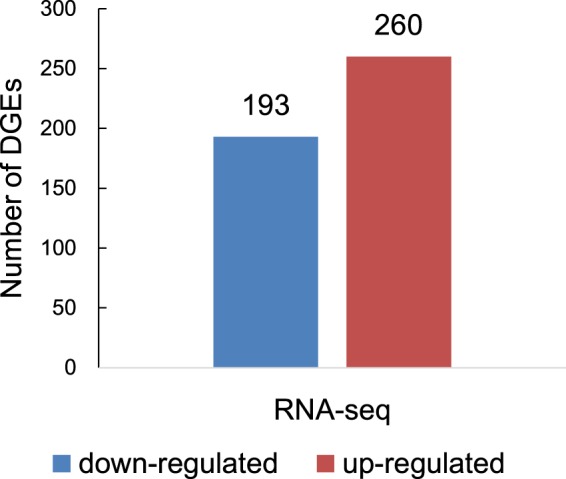

To identify differential expressed genes (DEGs) response to virus infection, comparison analysis between control and treated transcriptome libraries was performed. The expression level of genes were normalized by FPKM (expected number of fragments per kilobase of transcript sequence per millions base pairs sequenced). The pearson correlation values between two control (E1 and E3) and two treatment libraries (E2 and E4) were 0.964 and 0.948, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3c,d). Under the criterion of P-value ≤ 0.001 and |log2| ≥ 1.0, a total of 453 DEGs were found, including 260 up-regulated and 193 down-regulated genes (Fig. 5). The function of these genes were annotated by alignment with Nr and SWISSPROT Database (Supplementary Table S9). Functional annotation indicated that many disease resistance related genes were up-regulated after RBSDV infection. For example, glutathione S-transferase, lipoxygenase, lectin-like receptor protein kinase, O-methyltransferase 8, pathogenesis-related protein 10 and non-specific lipid-transfer protein, etc. (Supplementary Table S9).

Figure 5.

Different expressed genes in maize response to RBSDV.

In order to explore the functions of these differential expressed genes that are responsive to RBSDV infection, Gene ontology (GO), COG annotation and Pathway enrichment analysis were performed. From our dataset, 168 of 453 differential expressed genes have significant homologies in COG database and were assigned into 25 categories (Supplementary Table S9, Supplementary Fig. S4). Among them, “General function prediction only”, “Carbohydrate transport and metabolism”, “Replication, recombination and repair”, “Amino acid transport and metabolism” and “Energy production and conversion” ranked the top five categories (Supplementary Table S9, Supplementary Fig. S4). To further understand the metabolic and regulatory process for RBSDV-responsive, all up- and down-regulated genes were subjected to BGI WEGO program for GO analysis. The detailed summary of GO classification showed that cell, cell part, organelle were the most abundant ones in cell component categories. About molecular function category, the most abundant were binding and catalytic. The last category was biological process, in which cellular process, metabolic process, and response to stimulus were enriched (Supplementary Fig. S5).

According to KEGG analysis, 77 DEGs were annotated into 65 pathways. Among them, 23 pathways were enriched in response to RBSDV infection including two photosynthesis related pathways, photosynthesis and carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (Table 1). In addition, many DEGs were enriched in pathways involved in metabolite or secondary metabolite synthesis, such as starch and sucrose metabolism, pyruvate metabolism, butanoate metabolism, alanine, beta-Alanine metabolism, glutathione metabolism, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, suggesting significant metabolic changes after RBSDV infection. We found four genes, including a putative coronatine-insensitive protein (GRMZM2G035314, log2 = 2.16), a respiratory burst oxidase-like protein (GRMZM2G043435, log2 = 1.07), a heat shock protein HSP82 (GRMZM5G833699, log2 = 1.78) and one unknown protein (GRMZM2G151519, log2 = 1.44), were all enriched in plant-pathogen interaction pathway. Interestingly, these genes were all up-regulated in response to virus infection (Supplementary Table S9).

Table 1.

Enriched pathways in maize response to RBSDV.

| Number | Pathways | DEGs with pathway annotation (77) | All genes with pathway annotation (4137) | P-value | Pathway ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Photosynthesis | 8 (10.39%) | 124 (3%) | 1.93E-03 | ko00195 |

| 2 | Carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms | 7 (9.09%) | 97 (2.34%) | 1.97E-03 | ko00710 |

| 3 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | 7 (9.09%) | 135 (3.26%) | 1.21E-02 | ko00500 |

| 4 | Pyruvate metabolism | 5 (6.49%) | 85 (2.05%) | 2.02E-02 | ko00620 |

| 5 | Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism | 4 (5.19%) | 57 (1.38%) | 2.08E-02 | ko00250 |

| 6 | Butanoate metabolism | 3 (3.9%) | 32 (0.77%) | 2.09E-02 | ko00650 |

| 7 | Pentose phosphate pathway | 3 (3.9%) | 52 (1.26%) | 7.16E-02 | ko00030 |

| 8 | Cysteine and methionine metabolism | 4 (5.19%) | 85 (2.05%) | 7.25E-02 | ko00270 |

| 9 | Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 3 (3.9%) | 55 (1.33%) | 8.17E-02 | ko00630 |

| 10 | Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 2 (2.6%) | 27 (0.65%) | 8.90E-02 | ko00053 |

| 11 | beta-Alanine metabolism | 2 (2.6%) | 28 (0.68%) | 9.47E-02 | ko00410 |

| 12 | Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 5 (6.49%) | 135 (3.26%) | 1.05E-01 | ko00010 |

| 13 | Glutathione metabolism | 3 (3.9%) | 67 (1.62%) | 1.28E-01 | ko00480 |

| 14 | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 3 (3.9%) | 71 (1.72%) | 1.45E-01 | ko00940 |

| 15 | Fructose and mannose metabolism | 3 (3.9%) | 72 (1.74%) | 1.49E-01 | ko00051 |

| 16 | Limonene and pinene degradation | 1 (1.3%) | 9 (0.22%) | 1.56E-01 | ko00903 |

| 17 | ABC transporters | 1 (1.3%) | 9 (0.22%) | 1.56E-01 | ko02010 |

| 18 | Steroid biosynthesis | 2 (2.6%) | 39 (0.94%) | 1.63E-01 | ko00100 |

| 19 | Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis | 2 (2.6%) | 40 (0.97%) | 1.70E-01 | ko00290 |

| 20 | Stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid and gingerol biosynthesis | 1 (1.3%) | 10 (0.24%) | 1.71E-01 | ko00945 |

| 21 | Fatty acid biosynthesis | 2 (2.6%) | 41 (0.99%) | 1.77E-01 | ko00061 |

| 22 | Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 2 (2.6%) | 46 (1.11%) | 2.11E-01 | ko00040 |

| 23 | Plant-pathogen interaction | 4 (5.19%) | 129 (3.12%) | 2.18E-01 | ko04626 |

The expression of defense related genes response to RBSDV infection

Previous research has demonstrated that the expression of some defense response-related genes changed significantly when plants were suffered with biotic or abiotic stresses7,26,27. In this study, we investigated the expression changes of defense related genes, and found the expression of 90 defense related genes altered after RBSDV infection, including 53 receptor-like protein kinase genes, six WRKY DNA-binding protein genes, two NBS-LRR family genes, nine pathogenesis-related genes, 13 glutathione S-transferase genes, three peroxidase genes, one heat shock protein gene, one ferredoxin and two other disease resistance analog genes (Table 2). Receptor-like protein kinase was an important signal introduction factor involved in plant disease resistance28. As shown in Table 2, more than half of these defense related genes encoded diverse receptor-like protein kinases. Among them, the expression of 39 receptor-like protein kinase were up-regulated, while 14 of them were down-regulated upon virus infection. We found that the expression of some of these genes were altered dramatically, for example, the glutathione S-transferase gene (GRMZM2G146913) was up-regulated for about 30 times (log2 = 4.9274), the peroxidase gene (GRMZM2G313184) was up-regulated for about 24 times (log2 = 4.6027). These results provided important information for us to understand the mechanism under miRNA regulation of disease resistance in maize.

Table 2.

Differentially expressed defense related genes in response to RBSDV.

| Gene ID | Annotation | log2(TL/CL) |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor-like protein kinase | ||

| GRMZM2G576752 | WAK family receptor-like protein kinase | −1.0290 |

| GRMZM2G420882 | S-locus receptor-like protein kinase | 1.2255 |

| GRMZM2G063533 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase NAK | 0.8165 |

| GRMZM5G897958 | Receptor-like protein kinase HERK 1 | 0.9184 |

| GRMZM2G006080 | Receptor-like protein kinase | 0.8098 |

| GRMZM2G152901 | Receptor-like protein kinase | 1.0048 |

| GRMZM2G162702 | Receptor-like protein kinase | 2.0344 |

| GRMZM2G391794 | Receptor-like protein kinase | 1.3456 |

| GRMZM2G034855 | Receptor-like protein kinase | 0.7051 |

| GRMZM2G081957 | Receptor-like protein kinase | −1.1485 |

| GRMZM2G004207 | Receptor-like protein kinase | 1.2574 |

| GRMZM2G426917 | Receptor-like protein kinase | 1.1497 |

| GRMZM5G806108 | Receptor-like protein kinase | 1.3281 |

| GRMZM2G110968 | Receptor-like protein kinase | 1.8770 |

| GRMZM2G020158 | Protein kinase superfamily protein | −1.5095 |

| GRMZM2G473511 | Protein kinase superfamily protein | −1.0664 |

| GRMZM2G395778 | Protein kinase superfamily protein | −0.7861 |

| GRMZM2G068316 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase PERK9 | −1.2666 |

| GRMZM2G428964 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase PERK8 | −0.9519 |

| GRMZM5G832452 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase PERK4 | −1.1054 |

| GRMZM5G838420 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase PERK2 | 1.2050 |

| GRMZM2G055119 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase PERK10 | 1.6598 |

| GRMZM2G358365 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase | 3.2080 |

| AC202877.3_FG002 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase | 0.9396 |

| GRMZM5G872442 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase | 0.9015 |

| GRMZM2G024024 | LysM-domain receptor-like protein kinase | 1.9487 |

| GRMZM2G438007 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 0.9889 |

| GRMZM2G011806 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 1.3479 |

| GRMZM2G162829 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 2.0528 |

| GRMZM2G009995 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 2.1007 |

| GRMZM2G150448 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 0.9893 |

| GRMZM2G048294 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 0.8271 |

| GRMZM2G100234 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 1.0276 |

| GRMZM2G176206 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 0.7631 |

| GRMZM2G056903 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 2.0459 |

| GRMZM2G360219 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 2.6016 |

| GRMZM2G178753 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | −1.4082 |

| GRMZM2G104384 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | −0.8126 |

| GRMZM2G082191 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 0.9897 |

| GRMZM2G168917 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor protein kinase EXS precursor | 1.8846 |

| GRMZM2G123450 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor protein kinase | −1.4308 |

| GRMZM2G377199 | Lectin-domain receptor-like protein | −1.1165 |

| GRMZM2G017522 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase 42 | 1.8142 |

| GRMZM2G087625 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase 25 | 1.2029 |

| GRMZM2G338161 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase 2 | −1.2323 |

| GRMZM2G419318 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase | 1.4175 |

| GRMZM2G009506 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase | 1.6376 |

| GRMZM2G352858 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase | 1.2474 |

| GRMZM2G054023 | Lectin-like receptor protein kinase family protein | 0.8618 |

| GRMZM2G400694 | Lectin-like receptor protein kinase family protein | −1.1888 |

| GRMZM2G142037 | Lectin-like receptor protein kinase family protein | 2.8308 |

| GRMZM2G400725 | Lectin-like receptor protein kinase family protein | 0.8367 |

| GRMZM2G089819 | Brassinosteroid LRR receptor kinase precursor | 1.4135 |

| WRKY DNA-binding | ||

| GRMZM2G411766 | WRKY DNA-binding domain superfamily protein | −0.6117 |

| GRMZM2G149683 | WRKY DNA-binding domain superfamily protein | −1.6621 |

| GRMZM5G851490 | WRKY DNA-binding domain superfamily protein | 0.9215 |

| GRMZM2G377217 | WRKY DNA-binding domain superfamily protein | −1.7191 |

| GRMZM2G004060 | WRKY DNA-binding domain superfamily protein | 1.2294 |

| GRMZM2G060918 | WRKY DNA-binding domain superfamily protein | 2.1868 |

| NBS-LRR disease resistance gene | ||

| GRMZM2G005452 | NBS-LRR type disease resistance protein | 0.7430 |

| GRMZM2G092286 | TIR-NBS-LRR type disease resistance protein | 0.6914 |

| Pathogenesis-related | ||

| GRMZM2G156857 | Pathogenesis-related | 2.2732 |

| GRMZM2G474326 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 2 | −0.9431 |

| GRMZM2G008406 | Pathogenesis-related protein PR-1 precursor | 1.1899 |

| GRMZM2G112538 | Pathogenesis-related protein 10 | 2.8317 |

| GRMZM2G091742 | Pathogenesis-related protein 5 | −2.0124 |

| GRMZM2G075283 | Pathogenesis-related protein 1 | −1.0306 |

| GRMZM2G112488 | Pathogenesis-related protein 10 | 1.2337 |

| GRMZM2G154449 | Pathogenesis-related protein 5 | −1.0990 |

| GRMZM2G112524 | Pathogenesis-related protein 10 | 2.2167 |

| Glutathione S-transferase | ||

| GRMZM2G146475 | Glutathione S-transferase | −0.7240 |

| GRMZM2G161905 | Glutathione S-transferase GST 25 | 2.2247 |

| GRMZM2G129357 | Glutathione S-transferase GSTU1 | 1.1513 |

| GRMZM2G025190 | Glutathione S-transferase GSTU6 | 2.0181 |

| GRMZM2G032856 | Glutathione transferase24 | −0.7357 |

| GRMZM2G447632 | Glutathione S-transferase GSTU6 | 0.7859 |

| GRMZM2G335618 | Glutathione S-transferase GSTU1 | 2.3108 |

| GRMZM2G028821 | Glutathione S-transferase GSTU6 | 1.7805 |

| GRMZM2G161891 | Glutathione transferase35 | 1.9177 |

| GRMZM2G146913 | Glutathione S-transferase GSTU6 | 4.9274 |

| GRMZM2G064255 | Glutathione S-transferase zeta class | 0.8050 |

| GRMZM2G052571 | Glutathione S-transferase | 1.9679 |

| GRMZM2G056388 | Glutathione S-transferase GSTU6 | 1.6273 |

| Peroxidase | ||

| GRMZM2G313184 | Peroxidase R15 | 4.6027 |

| AC197758.3_FG004 | Peroxidase 52 precursor | 1.2116 |

| GRMZM2G135108 | Peroxidase | −1.1334 |

| Heat shock protein | ||

| GRMZM2G046382 | 17.4 kDa class I heat shock protein 3 | 0.7209 |

| Ferredoxin | ||

| GRMZM2G048313 | Ferredoxin2 | −1.0233 |

| Others | ||

| GRMZM2G116335 | Disease resistance analog PIC16 | 1.8963 |

| GRMZM2G443525 | Disease resistance protein At4g33300-like | 0.7199 |

Quantitative real-time PCR validation

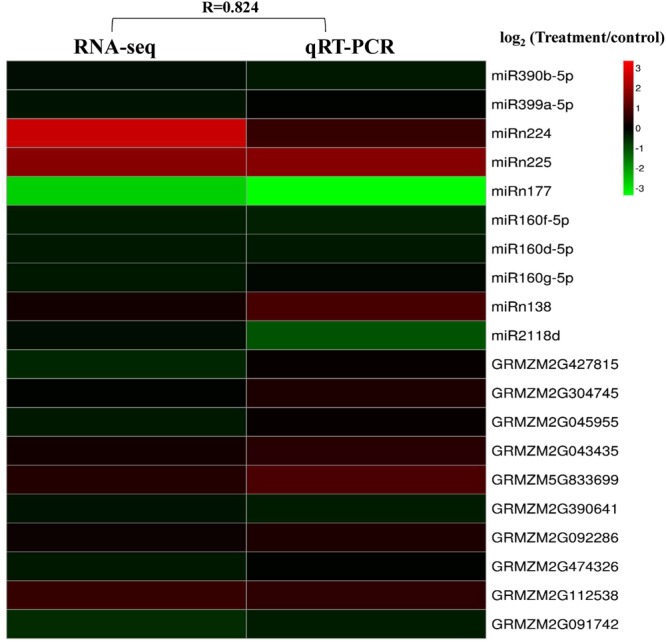

To validate the deep-sequencing data, we used quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to analyze the expression of miRNAs and mRNAs. Ten miRNAs were selected for qRT-PCR analysis including six known miRNAs and four novel miRNAs. Ten genes were also selected for qRT-PCR analysis. These genes included eight genes related with stress response and two genes related with hormone synthesis and metabolism (Fig. 6, Supplementary Table S10). Pearson correlation values between qRT-PCR and RNA-seq with R = 0.824, suggesting that the sequencing data was consistent with the qRT-PCR results.

Figure 6.

qRT-PCR verification of miRNAs and genes.

Discussion

Combined expression analysis of miRNAs and their targets after virus infection

In recent years, high-throughput sequencing method has become a powerful technology for global transcriptome and miRNAome analysis. It has been widely used in many plant species. Here, we simultaneous analyzed the miRNA and gene expression using the same samples before and after RBSDV infection. Through analyzing the relationship between miRNAs and their target genes, twelve miRNA-mRNA pairs were identified, which showed opposing expression patterns response to virus infection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Potential miRNA/target pairs of maize in response to RBSDV infection.

| miRNA family | miRNA name | Target genes | Relative expression level log2 (TL/CL) | Start-end position of target | Scores | Target annotation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNAs | Targets | ||||||

| Known miRNAs | |||||||

| MiR529 | zma-miR529–5p | GRMZM2G160917 | 4.23 | −1.2 | 1069–1088 | 2 | Squamosa promoter-binding-like protein 12 |

| zma-miR529–5p | GRMZM2G061734 | 4.23 | −1.7 | 936–956 | 2.5 | Squamosa promoter-binding-like protein 18 | |

| zma-miR529–5p | GRMZM2G126018 | 4.23 | −3.04 | 774–794 | 2.5 | Squamosa promoter-binding-like protein 17 | |

| MiR528 | zma-miR528b-5p | GRMZM2G045955 | 3.97 | −1 | 1261–1280 | 2.5 | Zea mays rust resistance protein rp3–1 |

| MiR408 | zma-miR408b-3p | GRMZM2G331566 | 4.62 | −1.84 | 174–193 | 3 | Endoglucanase |

| MiR399 | zma-miR399d-5p | GRMZM2G310674 | 1.98 | −1.57 | 405–425 | 3 | RNA exonuclease 1 |

| MiR398 | zma-miR398b-5p | GRMZM2G448151 | 2.66 | −1.87 | 881–901 | 3 | Small subunit ribosomal protein S3 |

| MiR156 | zma-miR156k-5p | GRMZM2G061734 | 1.64 | −1.7 | 941–961 | 1 | Squamosa promoter-binding-like protein 18 |

| zma-miR156k-5p | GRMZM2G160917 | 1.64 | −1.2 | 812–831 | 1 | Squamosa promoter-binding-like protein 14 | |

| Candidate novel miRNAs | |||||||

| zma-miRn53 | GRMZM2G076468 | 1.04 | −4.12 | 632–651 | 2 | Cyclin-P4–1 | |

| zma-miRn138 | GRMZM2G160917 | 1.66 | −1.2 | 814–834 | 3 | Squamosa promoter-binding-like protein 14 | |

| zma-miRn194 | GRMZM2G484653 | 1.15 | −1.31 | 102–121 | 2 | Unknown | |

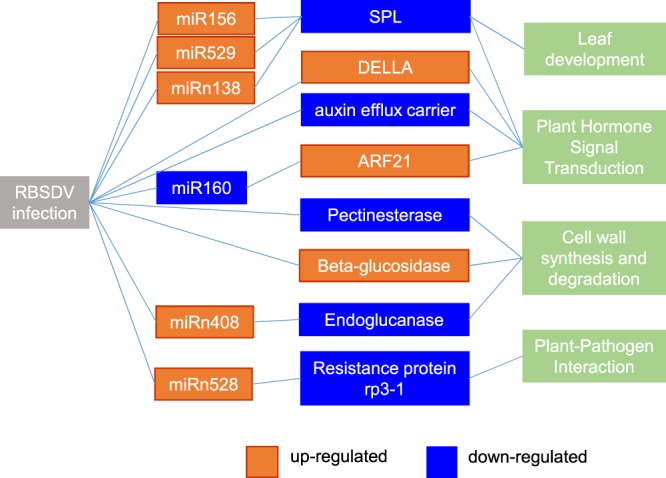

In rice, miR156/miR529 and SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING LIKE PROTEIN (SPL) genes constituted a spatiotemporally coordinated gene network which playing an important regulation roles in tiller and panicle branching29,30. Plant SPL genes were involved in leaf development, gibberellin response, light signaling, copper homeostasis, response to stresses, and positively regulate inflorescence meristem29. We found miR529 were up-regulated in the virus infected samples, and the expression of its three target genes (SPL genes) were all down-regulated after infected with virus in maize (Table 3, Fig. 7). These results were coincided with the significant phenotype changes of virus infected maize, including the abnormal leaf morphology, dwarf, and the abnormality in vegetative and reproductive growth. One target gene of miR528, which was down-regulated after RBSDV infection, is highly homologous with maize rust resistance protein rp3–1, an important defense gene in maize rust resistance caused by Puccinia sorghi31. One of the target gene of miR408b-3p is endoglucanase, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of cellulose. Our results showed that miR408b-3p was up-regulated significantly, while its target gene was down-regulated upon virus infection (Table 2, Fig. 7). In addition, the expression trend of miR399d-5p, miR398b-5p and miR156k showed a negative correlation with their target genes. Three novel miRNA-mRNA pairs were identified, of which GRMZM2G076468 encodes a cyclin-dependent protein kinase (Cyclin-P4–1), is the target of zma-miRn53. GRMZM2G160917 is a SPL gene and regulated by zma-miRn138. Zma-miRn194 targeted GRMZM2G484653, a gene annotated as unknown function (Table 2, Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Potential regulatory roles of miRNAs and their targets in maize response to RBSDV.

Accumulated evidence indicated that many plant endogenous miRNAs were responsive to pathogenic fungus and virus infection and played important roles in plant disease resistance, such as miR398, miR16016, miR482, miR211817, and miR47218. After infection with Magnaporthe Oryzae, the expression of rice miR398 was induced both in susceptible and resistant lines, while miR160 were only induced in resistant lines, and overexpression of miR160a or miR398b can enhance rice resistance to the disease16. Here, we found that the accumulation of miR398 were significantly induced to higher levels upon RBSDV infection, and miR160a decreased upon RBSDV infection (Supplementary Table S3, Fig. 7). The expression trend of miR160 and miR398 in susceptible maize variety B73 was consistent with that in susceptible lines of rice after infected with pathogen. These results suggested miR160 and miR398 might played great roles in maize disease resistance. In addition, miR482, miR2118 and miR472 contribute to plant immunity through negative regulation of R gene17,18. However, the expression level of miR2118 was very low, while miR482 and miR472 were not detected in our dataset.

The expression of genes that involved in dwarf symptoms

After infected with RBSDV, the growth and development of maize exhibited severe abnormalities, such as dwarf, dark green leaf, and failure of completing the reproductive growth in most cases2,32. The height of plants is shown to correlate with the composition of the cell wall, which are associated with metabolism and biosynthesis of cellulose, lignin, hemicellulose and pectin7,33,34. Cellulose is a major class of polysaccharide, which is the main ingredients of plant cell wall, and was closely relative to plant defense35. We identified a variety of gene families involved in cell wall synthesis and degradation, and the expression of these genes altered when the maize infected by RBSDV (Table 4). These genes included 13 cellulose synthase, seven endoglucanase, two glycoside transferase, one glycosyltransferase, five pectin related genes, three glucosidase, galacturonase, one putative mixed-linked glucan synthase and one glycine-rich cell wall structural protein gene (Table 4). Cellulose synthase is an important enzymes important in cellulose synthesis system. In the present study, nine cellulose synthase genes were up-regulated and three cellulose synthase genes were down-regulated upon virus infection. Endoglucanase is a specific enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of cellulose, and the expression of seven endoglucanase encoding genes was altered, five were up-regulated, and two were down-regulated (Table 4). Beta-glucosidase catalyzes the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds, and a variety of glycosidic conjugates of hormones and defense compounds can be hydrolyzed by beta-glucosidases. Here, we found three beta-glucosidases were up-regulated upon the RBSDV infection. The gene encoding a beta-glucosidases 18 gene was up-regulated for almost thirty times. The up-regulated expression of beta-glucosidases might lead to the degradation of defense compounds, and then resulting in the collapse of maize defense system.

Table 4.

Expression profile of cell wall synthesis and degradation related genes in response to RBSDV infection.

| Gene ID | Annotation | log2(TL/CL) | Expression trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose synthase | |||

| GRMZM2G111642 | cellulose synthase5 | 0.918326826 | up |

| GRMZM2G018241 | cellulose synthase-9 | 0.964970747 | up |

| GRMZM2G424832 | cellulose synthase-4 | 0.728567596 | up |

| GRMZM2G378836 | cellulose synthase A catalytic subunit 6 | 2.180462068 | up |

| GRMZM2G112336 | cellulose synthase A catalytic subunit 10 | 1.787277899 | up |

| GRMZM2G122431 | cellulose synthase-like protein | 0.785875406 | up |

| GRMZM2G027723 | cellulose synthase A catalytic subunit 2 | 1.04980425 | up |

| GRMZM2G028353 | cellulose synthase-7 | 1.166988119 | up |

| GRMZM2G025231 | cellulose synthase7 | 1.535744163 | up |

| GRMZM2G339645 | cellulose synthase-like | −0.706432842 | down |

| GRMZM2G142898 | cellulose synthase A catalytic subunit 7 | −1.05281387 | down |

| GRMZM5G876395 | cellulose synthase A catalytic subunit 3 | −0.971682697 | down |

| GRMZM2G014558 | cellulose synthase-like protein E6 | −0.739728946 | down |

| Glucanase | |||

| GRMZM2G125991 | endoglucanase 7 | 1.288855833 | up |

| GRMZM2G154678 | endoglucanase 16 | 2.481411225 | up |

| GRMZM2G482256 | endoglucanase 5 | 0.73974828 | up |

| GRMZM2G147849 | endo-1,4-beta-glucanase Cel1 | 0.677179814 | up |

| GRMZM2G147849 | endo-1,4-beta-glucanase | 0.677179814 | up |

| GRMZM2G076348 | endo-1,3;1,4-beta-D-glucanase | −0.741829982 | down |

| GRMZM2G331566 | endoglucanase | −1.836085972 | down |

| Glycoside transferase | |||

| GRMZM2G178025 | glycoside transferase | 1.034966325 | up |

| AC199765.4_FG008 | glycoside transferase | 0.971121742 | up |

| Glycosyltransferase | |||

| GRMZM2G028286 | xyloglucan glycosyltransferase 10 | 1.213435877 | up |

| Pectin related | |||

| GRMZM2G131912 | pectate lyase 8 | −0.684198742 | down |

| GRMZM2G043415 | pectinesterase | −1.700156416 | down |

| GRMZM2G019411 | pectinesterase-1 | −0.593443161 | down |

| GRMZM2G455564 | pectinesterase 8 | −0.755441006 | down |

| GRMZM2G012328 | pectinesterase inhibitor | −1.107158277 | down |

| Glucosidase | |||

| GRMZM2G031628 | Beta-glucosidase 18 | 4.935523594 | up |

| GRMZM2G148176 | Beta-glucosidase 8 | 1.810324677 | up |

| AC234160.1_FG003 | Beta-glucosidase 1 | 1.014596947 | up |

| Galacturonase | |||

| GRMZM2G026855 | polygalacturonase | 0.796011447 | up |

| GRMZM2G333980 | polygalacturonase inhibitor 1 | 0.952508693 | up |

| GRMZM2G004435 | polygalacturonase | 1.153591577 | up |

| GRMZM2G121312 | polygalacturonase inhibitor 2 | 1.257111081 | up |

| GRMZM2G052844 | polygalacturonas | 2.586290183 | up |

| GRMZM2G467435 | polygalacturonas | 0.933885674 | up |

| GRMZM2G002034 | polygalacturonas | 0.785210875 | up |

| GRMZM2G038281 | Beta-galactosidase 3 | 2.386748111 | up |

| GRMZM2G178106 | Beta-galactosidase 5 | 1.966547727 | up |

| GRMZM2G417455 | Beta-galactosidase 3 | −1.253589062 | down |

| GRMZM2G127123 | Beta-galactosidase 4 | −0.841155087 | down |

| GRMZM2G170388 | polygalacturonase precursor | −0.726971784 | down |

| GRMZM2G167786 | polygalacturonase inhibitor 1 | −1.296047742 | down |

| GRMZM2G030265 | exopolygalacturonase | −1.09989177 | down |

| GRMZM2G174708 | polygalacturonase inhibitor 1 precursor | −2.018772527 | down |

| Other genes related cell wall structure | |||

| GRMZM2G103972 | putative mixed-linked glucan synthase 1 | −1.363662044 | down |

| GRMZM2G109959 | glycine-rich cell wall structural protein | 2.392335992 | up |

Plant height is regulated by hormones, such as gibberellins (GAs), auxin (IAA) and brassinosteroid36–38. In maize, genes that have large effects on plant height have been well characterized, and most of them were involved in hormone synthesis, transport, and signaling, for example, brachytic238, dwarf339 and nana plant140. In this study, a total of 17 GA biosynthesis and signaling genes were up- or down-regulated upon RBSDV infection, including two DELLA protein genes, four gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase genes, seven gibberellin receptor GID1 genes, two gibberellin 20 oxidase (GA20ox) genes, one chitin-inducible gibberellin-responsive gene and one putative response to gibberellin stimulus genes (Table 5). Auxin plays essential roles in regulating plant growth and development, and also regarded as a negative regulator for plant disease resistance41,42. In response to RBSDV infection, the expression of many auxin synthesis and transport related genes was alerted. Among them, seven and four auxin responsive factor (ARF) genes were up- and down-regulated upon RBSDV infection, respectively (Table 5). For example, GRMZM2G390641, encoding ARF21 gene, was regulated by zma-miR160d-5p and miRn91 (Supplementary Table S5-S6).

Table 5.

Expression profile of gibberellin and auxin related genes in response to RBSDV infection.

| Gene ID | Annotation | log2(TL/CL) | Expression trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| DELLA | |||

| GRMZM2G001426 | DELLA protein | 0.880628985 | up |

| GRMZM2G013016 | DELLA protein | 0.828562365 | up |

| Gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase | |||

| GRMZM2G152354 | gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase | 1.370160759 | up |

| GRMZM2G031432 | gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase | 2.637072082 | up |

| GRMZM2G051619 | gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase | 3.010518964 | up |

| GRMZM2G006964 | gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase 8 | −1.351721572 | down |

| Gibberellin receptor GID1 | |||

| GRMZM2G301934 | gibberellin receptor GID1L2 | 1.559501317 | up |

| GRMZM2G420786 | gibberellin receptor GID1L2 | 0.693598092 | up |

| GRMZM2G111421 | gibberellin receptor GID1L2 | 0.701789901 | up |

| GRMZM2G173630 | GID1-like gibberellin receptor | 0.740894975 | up |

| GRMZM2G016605 | gibberellin receptor GID1 | 1.446037371 | up |

| GRMZM2G049675 | gibberellin receptor GID1L2 | 0.860587685 | up |

| GRMZM5G831102 | gibberellin receptor GID1L2 precursor | −0.623988411 | down |

| Gibberellin 20 oxidase | |||

| GRMZM2G050234 | gibberellin 20 oxidase | 2.41338231 | up |

| AC203966.5_FG005 | gibberellin 20 oxidase 1 | 1.916779027 | up |

| Other genes related gibberellin | |||

| GRMZM2G098517 | chitin-inducible gibberellin-responsive | 0.705234195 | up |

| AC205471.4_FG007 | unknown (response to gibberellin stimulus) | 3.204932625 | up |

| Auxin response factor (ARF) | |||

| GRMZM2G028980 | auxin response factor 16 (ARF16) gene | 1.151955362 | up |

| GRMZM2G081158 | auxin response factor 9 (ARF9) gene | 1.65654925 | up |

| GRMZM2G153233 | auxin response factor 2 (ARF2) gene | 1.413686542 | up |

| GRMZM2G073750 | auxin response factor 9 (ARF9) gene | 0.732854439 | up |

| GRMZM2G703565 | auxin response factor 5 (ARF5) gene | 1.991605559 | up |

| GRMZM2G035405 | auxin response factor 18 (ARF18) gene | 1.186726815 | up |

| GRMZM2G078274 | auxin response factor 3 (ARF3) gene | 0.743864138 | up |

| GRMZM2G034840 | auxin response factor 4 (ARF4) gene | −1.391198729 | down |

| GRMZM2G390641 | auxin response factor 21 (ARF21) gene | −0.790919233 | down |

| GRMZM2G137413 | auxin response factor 14 (ARF14) gene | −0.720913025 | down |

| GRMZM2G437460 | auxin response factor 12 (ARF12) gene | −0.975080801 | down |

| Other auxin response genes | |||

| GRMZM2G154332 | SAUR12-auxin-responsive | 1.109550229 | up |

| GRMZM2G057067 | IAA6-auxin-responsive | 0.961062035 | up |

| GRMZM2G138268 | auxin-responsive protein | 0.89357466 | up |

| GRMZM5G864847 | IAA16-auxin-responsive | 0.784317249 | up |

| GRMZM5G835903 | SAUR55-auxin-responsive | −0.84926364 | down |

| GRMZM2G343351 | SAUR44-auxin-responsive | −0.882790627 | down |

| GRMZM2G465383 | SAUR25-auxin-responsive | −1.212035079 | down |

| IAA synthesis | |||

| GRMZM2G053338 | Indole-3-acetic acid amido synthetase (GH3) | 3.923877451 | |

| Auxin transporter-like protein | |||

| GRMZM2G126260 | auxin efflux carrier PIN10a (PIN10a) | 1.74186011 | up |

| GRMZM2G025742 | auxin efflux carrier component 6 | −1.948711258 | down |

| GRMZM2G098643 | auxin efflux carrier | −0.830424288 | down |

| GRMZM2G382393 | auxin Efflux Carrier family protein | −1.373387099 | down |

| GRMZM2G171702 | auxin efflux carrier PIN1d (PIN1d) gene | −0.772559276 | down |

| GRMZM2G025659 | auxin efflux carrier PIN5a (PIN5a) gene | −1.188365531 | down |

| GRMZM2G175983 | auxin efflux carrier PIN5a (PIN5a) gene | −2.788212274 | down |

| GRMZM2G149481 | auxin transporter-like protein 3 | −2.689255972 | down |

Auxin polar transport is essential for the formation and maintenance of local auxin gradients of plant43,44. Auxin efflux carriers PIN family genes played important roles in auxin polar transport. Loss of function of PIN genes severely affected organ initiation. For example, the auxin transport-defective mutants br2 and sem1 showed dwarf phenotype and vasculature defects43. Here, the expression level of seven auxin efflux carrier genes were decreased after virus infection (Table 5). It is possible that the decreasing expression of auxin efflux carrier protein genes could be a major reason that caused the dwarf phenotype after maize infected by RBSDV.

In conclusion, we identified 302 miRNAs and 351 potential target genes in maize. The expression patterns of 81 miRNAs differed dramatically upon RBSDV infection. Combined small RNA and gene expression analysis identified 12 miRNA-mRNA pairs with opposite expression patterns response to virus infection, and six of them are likely to play significant roles in the formation of maize disease symptoms. This study provided insight into the roles of miRNAs in response to RBSDV, and could help to develop novel strategy for crops against virus infection.

Materials and Methods

Zea mays B73 was planted in the field where the RBSDV disease happened seriously almost every year. As the control, the plants were covered with a net to prevent the planthoppers. Leaves of one-month-old maize seedlings with rough dwarf disease symptoms were collected. Total RNA were prepared separated from each individual sample using RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara, Dalian, China), following by RNase-free DNase treatment (Takara, Dalian, China). RNA concentration was quantified by Eppendorf BioPhotometer plus UV-Visible Spectrophotometer. The cDNA were synthesis using One Step PrimeScript miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Dalian, China) according the manufacturer’s instructions. According to the sequences of RBSDV segment S6 and S7 (HF955010, HF955011), two pair of primers pS6–604 (5′-CCTAGTTCTCCGCAAGCC-3′, 5′-CAGGGACAGTTCCAATCATAAA-3′) and pS7–342 (5′- TCAGCAAAAGGTAAAGGAAGG -3′, 5′- GCTCCTACTGAGTTGCCTGTC-3′) were designed. Samples were collected according the method in previous studies7,45. Every ten virus infected seedlings which can be detected by both the primer pS6–604 and pS7–342 were harvested as one sample, and three more samples were prepared by the same method as replicates.

Construction and sequencing of small RNA libraries

Small RNA libraries were constructed as described in the previous studies15,46. Briefly, low molecular weight RNAs (10 nt - 40 nt) were isolated from the total RNA by electrophoresis using 15% TBE-urea denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Then, the 5′ and 3′ adaptors were added and reverse transcription was performed to synthesize cDNA. And cDNA libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSeqTM 2000. The sequencing was accomplished by BGI small RNA pipeline (BGI, Shenzhen, China). After sequencing, clean reads were generated by removing the adapter sequences and low quantity reads (reads having ‘N’, <18 nt, and >29 nt). Then clean reads were used to align with maize B73 RefGen_V2 genome (http://archive.maizesequence.org/index.html), GenBank and Rfam database, and miRbase (http://www.mirbase.org/). The detail processes to identify known and novel miRNAs were according to the method described in previous studies47.

Transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Transcriptome libraries were constructed using Illumina sample preparation kits. Briefly, poly A mRNAs were isolated and cut to short fragments. The short mRNA fragments were then used to synthesize the first strand cDNA using random hexamers primers. Then, dNTPs, RNase H, buffer and DNA polymerase I were added to synthesize the second strand cDNA. cDNAs were further purified using QiaQuick PCR kit. Then, polyA tails and adaptors were added and the DNA fragments with suitable size were recovered from gel. Finally, the cDNA were amplified by PCR, followed by sequencing using Illumina HiSeq™ 2000.

After sequencing, raw data was filtered to generate clean reads by removing adaptor sequences, reads containing multiple N and lower quality reads. Then, the clean reads were used to compare with maize genome sequences (B73 RefGen_V2, release 5b.60) using SOAPaligner/SOAP2 with the parameters that mismatch ≤248. The gene expression level is calculated by using FPKM method49. Differential expression analysis of two samples was performed using rigorous algorithm method with P-value ≤ 0.001 and the absolute value of log2Ratio ≥1. Gene function analysis was carried out by BLASTx searches against the UniProt database and the Swiss-Prot protein database (http://www.expasy.ch/ sprot). Gene Ontology (GO) annotation analysis was based on WEGO (http://wego.genomics.org.cn/cgi-bin/wego/index.pl). Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) classification analysis was based on the database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/). Pathway-based analysis was performed according to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathway (KEGG) database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/).

qRT-PCR Validation

For qRT-PCR validation of miRNAs, the Mir-X miRNA qRT-PCR SYBR Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc) were used following the manufacturer’s instructions. For all miRNAs and genes, the qRT-PCR was performed in ABI7500 (Applied Biosystems). Primers used for qRT-PCR were listed in Supplementary Table S11. All reactions were performed in biological triplicates. For qRT-PCR analysis of miRNAs and mRNAs, U6 RNA and ubiquitin were used as the internal control, respectively. The relative expression of all mRNAs and miRNAs were calculated using 2−ΔΔct method.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (ZR2017MC005, ZR2015YL061, 2014ZRB01507, ZR2015CQ012 and ZR2018BC029), Shandong Province Germplasm Innovation and Utilization Project (2016LZGC025), Agricultural Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CXGC2016B02) and Young Talents Training Program of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Author Contributions

X.W. and C.Z. conceived and designed the experiments. A.L., G.L., Y.Z., C.L., Z.M., M.Z., Y.Z., H.X., S.Z. and L.H. performed the experiments. C.Z., C.M., P.L. and Y.Z. analyzed data. C.Z. and X.W. wrote and revised the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Aiqin Li and Guanghui Li contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Chuanzhi Zhao, Email: chuanzhiz@126.com.

Xingjun Wang, Email: xingjunw@hotmail.com.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-31919-z.

References

- 1.Zhang H, Chen J, Lei J, Adams MJ. Sequence Analysis Shows that a Dwarfing Disease on Rice, Wheat and Maize in China is Caused by Rice Black-streaked Dwarf Virus. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2001;107:563–567. doi: 10.1023/A:1011204010663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao X, et al. Enhanced virus resistance in transgenic maize expressing a dsRNA-specific endoribonuclease gene from E. coli. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryals JA, et al. Systemic Acquired Resistance. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1809–1819. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomma BP, Penninckx IA, Broekaert WF, Cammue BP. The complexity of disease signaling in Arabidopsis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:63–68. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(00)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinha M, et al. Current overview of allergens of plant pathogenesis related protein families. Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014:543195. doi: 10.1155/2014/543195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper B. Collateral gene expression changes induced by distinct plant viruses during the hypersensitive resistance reaction in Chenopodium amaranticolor. Plant J. 2001;26:339–349. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jia MA, et al. Alteration of gene expression profile in maize infected with a double-stranded RNA fijivirus associated with symptom development. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13:251–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu F, Shu J, Jin W. Identification and validation of miRNAs associated with the resistance of maize (Zea mays L.) to Exserohilum turcicum. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xin M, et al. Diverse set of microRNAs are responsive to powdery mildew infection and heat stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu D, Mou G, Wang K, Zhou G. MicroRNAs responding to southern rice black-streaked dwarf virus infection and their target genes associated with symptom development in rice. Virus Res. 2014;190:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao C, et al. Small RNA and Degradome Deep Sequencing Reveals Peanut MicroRNA Roles in Response to Pathogen Infection. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2015;33:1013–1029. doi: 10.1007/s11105-014-0806-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuck G, Candela H, Hake S. Big impacts by small RNAs in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Bartel B. MicroRNAS and their regulatory roles in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:19–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinhart BJ, Weinstein EG, Rhoades MW, Bartel B, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs in plants. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1616–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.1004402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Q, et al. Genome-wide identification of Thellungiella salsuginea microRNAs with putative roles in the salt stress response. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, et al. Multiple rice microRNAs are involved in immunity against the blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Plant Physiol. 2014;164:1077–1092. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.230052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shivaprasad PV, et al. A microRNA superfamily regulates nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich repeats and other mRNAs. Plant Cell. 2012;24:859–874. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.095380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boccara M, et al. The Arabidopsis miR472-RDR6 silencing pathway modulates PAMP- and effector-triggered immunity through the post-transcriptional control of disease resistance genes. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003883. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang M, Zhao Q, Zhu D, Yu J. Characterization of microRNAs expression during maize seed development. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:360. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong X, et al. System analysis of microRNAs in the development and aluminium stress responses of the maize root system. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014;12:1108–1121. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H, et al. Identification of miRNAs and their target genes in developing maize ears by combined small RNA and degradome sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chuck GS, et al. Overexpression of the maize Corngrass1 microRNA prevents flowering, improves digestibility, and increases starch content of switchgrass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17550–17555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113971108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuck G, Meeley R, Irish E, Sakai H, Hake S. The maize tasselseed4 microRNA controls sex determination and meristem cell fate by targeting Tasselseed6/indeterminate spikelet1. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1517–1521. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajagopalan R, Vaucheret H, Trejo J, Bartel DP. A diverse and evolutionarily fluid set of microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3407–3425. doi: 10.1101/gad.1476406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers BC, et al. Criteria for annotation of plant MicroRNAs. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3186–3190. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marathe R, Guan Z, Anandalakshmi R, Zhao H, Dinesh-Kumar SP. Study of Arabidopsis thaliana resistome in response to cucumber mosaic virus infection using whole genome microarray. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;55:501–520. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-0439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satoh K, et al. Selective modification of rice (Oryza sativa) gene expression by rice stripe virus infection. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:294–305. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015990-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruijt M, DE Kock MJ, de Wit PJ. Receptor-like proteins involved in plant disease resistance. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:85–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, et al. Coordinated regulation of vegetative and reproductive branching in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:15504–15509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521949112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H, Wang H. The miR156/SPL Module, a Regulatory Hub and Versatile Toolbox, Gears up Crops for Enhanced Agronomic Traits. Mol Plant. 2015;8:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webb CA, et al. Genetic and molecular characterization of the maize rp3 rust resistance locus. Genetics. 2002;162:381–394. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.1.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milne RG, Lovisolo O. Maize rough dwarf and related viruses. Adv Virus Res. 1977;21:267–341. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60764-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somerville C. Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:53–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.022206.160206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reiter WD, Chapple CC, Somerville CR. Altered growth and cell walls in a fucose-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis. Science. 1993;261:1032–1035. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5124.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aidemark M, et al. Trichoderma viride cellulase induces resistance to the antibiotic pore-forming peptide alamethicin associated with changes in the plasma membrane lipid composition of tobacco BY-2 cells. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:274. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peiffer JA, et al. The genetic architecture of maize height. Genetics. 2014;196:1337–1356. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.159152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Ni Z, Yao Y, Nie X, Sun Q. Gibberellins and heterosis of plant height in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) BMC Genet. 2007;8:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Multani DS, et al. Loss of an MDR transporter in compact stalks of maize br2 and sorghum dw3 mutants. Science. 2003;302:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1086072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawit SJ, Wych HM, Xu D, Kundu S, Tomes DT. Maize DELLA proteins dwarf plant8 and dwarf plant9 as modulators of plant development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1854–1868. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartwig T, et al. Brassinosteroid control of sex determination in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19814–19819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108359108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Navarro L, et al. A plant miRNA contributes to antibacterial resistance by repressing auxin signaling. Science. 2006;312:436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.1126088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu J, et al. Manipulating broad-spectrum disease resistance by suppressing pathogen-induced auxin accumulation in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:589–602. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.163774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forestan C, Varotto S. The role of PIN auxin efflux carriers in polar auxin transport and accumulation and their effect on shaping maize development. Mol Plant. 2012;5:787–798. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forestan C, Farinati S, Varotto S. The Maize PIN Gene Family of Auxin Transporters. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:16. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimizu T, Satoh K, Kikuchi S, Omura T. The repression of cell wall- and plastid-related genes and the induction of defense-related genes in rice plants infected with Rice dwarf virus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:247–254. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-3-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao CZ, et al. Deep sequencing identifies novel and conserved microRNAs in peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao M, et al. Cloning and characterization of maize miRNAs involved in responses to nitrogen deficiency. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li R, et al. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.