Abstract

Environmental variation favors the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. For many species, we understand the costs and benefits of different phenotypes, but we lack a broad understanding of how plastic traits evolve across large clades. Using identical experiments conducted across North America, we examined prey responses to predator cues. We quantified five life history traits and the magnitude of their plasticity for 23 amphibian species/populations (spanning three families and five genera) when exposed to no cues, crushed-egg cues, and predatory crayfish cues. Embryonic responses varied considerably among species and phylogenetic signal was common among the traits whereas phylogenetic signal was rare for trait plasticities. Among trait-evolution models, the Ornstein Uhlenbeck (OU) model provided the best fit or was essentially tied with Brownian motion. Using the best fitting model, evolutionary rates for plasticities were higher than traits for three life history traits and lower for two. These data suggest that the evolution of life history traits in amphibian embryos is more constrained by a species’ position in the phylogeny than by life history plasticity. The fact that an OU model of trait evolution was often a good fit to patterns of trait variation may indicate adaptive optima for traits and their plasticities.

Keywords: phylogenetic inertia, Rana, Lithobates, Hyla, Pseudacris, Anaxyrus

Introduction

Most organisms in nature experience environmental variation. In response to this variation, many species have evolved traits that are induced by the environment to produce alternative, adaptive phenotypes (i.e., phenotypically plastic traits). As a result, we have an excellent understanding of plasticity in numerous traits from a wide range of plants, animals, fungi, protists, and bacteria and from a variety of biological disciplines including genetics, molecular biology, developmental biology, and ecology (see reviews by Schlichting and Pigliucci 1998, West-Eberhard 2003, DeWitt and Scheiner 2004, Callahan et al. 2008, Murren et al. 2014, 2015). Although adaptive plasticity is ubiquitous, our understanding in any particular system typically comes from intensive investigations on a limited set of species within a clade. What has been missing in this endeavor has been the examination of broad patterns of plasticity evolution across a clade within a phylogenetic perspective.

The study of phylogenetics has enjoyed a rich history in biology as a way of understanding the evolutionary relationships among species (Grant 1986, Harvey and Pagel 1991, Schluter 2000, Berendonk et al. 2003, Felsenstein 2004). There has been increased interest in using phylogenies as a map onto which the species’ ecology and traits can be overlaid to determine whether species possess similar traits due to a shared history or due to similar selective forces that produce convergence (Losos 1990, Winemiller 1991, Cadle and Greene 1993, Losos et al. 1998, McPeek and Brown 2000, Price et al. 2000, Webb et al. 2002, Stephens and Wiens 2004, see Special Feature of Ecology, 2012 Supplement).

Given the power of a phylogenetic perspective, it is not surprising that there have been repeated calls for the integration of phylogenetics and phenotypic plasticity beyond the traditional examination of closely related populations or congeners (Doughty 1995, Diggle 2002, Pigliucci et al. 2003, Murren et al. 2015). By assessing the directions and magnitudes of adaptive trait changes for a large number of related species, we can address important evolutionary questions. One question of particular interest is whether, like most morphological and ecological traits, trait plasticity exhibits phylogenetic signal (defined as a pattern where trait disparity scales with the phylogenetic distance that separates species; Blomerg et al. 2003, Revell et al. 2008, Losos 2008). Environmental variation poses diverse challenges to species performance, but it is clear that species can evolve a variety of effective plastic strategies (Boersma et al. 1998, Pigliucci 2001, West-Eberhard 2003). As a result, we might expect different clades within a phylogenetic group to either evolve particular types of plasticity in response to environmental variation (i.e., morphological, behavioral, or physiology) or evolve a range of unique combination of non-plastic phenotypes that are similarly effective in the particular environment. The existence of phylogenetic signal can represent a level of phylogenetic inertia that could constrain how traits or trait plasticity can evolve, in the sense that close relatives will be constrained to have similar trait values due to shared descent. Although we know a good deal about the phylogenetic signal of traits (see above citations), we know considerably less about the presence of phylogenetic signal in the plasticity of traits (Pigliucci et al. 1999, Pollard et al. 2001, Pigliucci et al. 2003, Thaler and Karban 1997, Colbourne et al. 1997, Gomez-Mestre et al. 2008, Burns and Strauss 2012).

If we could map traits and trait plasticity onto a phylogeny, we could also examine questions about rates of evolution. We could compare rates of evolution among different types of traits (e.g., behavior, morphology, life history) and different magnitudes of trait plasticity. Rates of evolution have been investigated in many different studies of species’ traits, but there appear to be no studies that have compared the rates of trait evolution to rates of plasticity evolution. Thus, it remains an open question whether traits evolve slower or faster than trait plasticity. Answering this question should provide insights into the role that phylogenetic relationships play in constraining the evolution of phenotypically plastic traits, and whether species traits or trait plasticity will be able to shift more quickly in the face of environmental change.

In this study, we examined the phylogenetic patterns of phenotypic plasticity using amphibians, a model system that has become well known for exhibiting predator-induced behavioral, morphological, and life history traits (Van Buskirk 2002, Miner et al. 2005, Relyea 2007). Our focus was to examine how amphibian embryos respond to predators. Predators of eggs (e.g., crayfish, snakes, and leeches) induce several species of amphibians to hatch earlier and with a smaller mass or at a less-developed stage whereas other species are unresponsive (Warkentin 1995, Chivers et al. 2001, Laurila et al. 2001, 2002, Johnson et al. 2003, Saenz et al. 2003, Orizaola and Braña 2004, Vonesh 2005, Gomez-Mestre et al. 2008, Anderson and Brown 2009, Segev et al. 2015). From the studies that have been conducted on amphibian embryos (encompassing 12 families), one can conclude that predator-induced developmental plasticity exists in some but not all species. Because most of these experimental efforts thus far have examined only one or two species at a time (using a variety of experimental conditions and predator species), we have relatively few comparable data on the directions and magnitudes of these responses. We also lack a general understanding of the phylogenetic constraints and ecological conditions under which these responses have evolved (but see Gomez-Mestre et al. 2008). Clearly, a phylogenetic approach is well suited to examine this question.

We addressed the following hypotheses: 1) Amphibian embryos will respond to predator cues by hatchling earlier, less developed, and at a smaller size, 2) Different species of amphibian embryos will differ in their traits and trait plasticity in response to predation risk, 3) There will be phylogenetic signal in the traits and trait plasticity of amphibian embryos, and 4) The rates of evolution will be similar between traits and trait plasticity, when estimated using the best fitting model of character evolution.

Methods

The challenges

When taking a phylogenetic approach to quantifying ecologically important traits, a number of challenges arise (for both plastic and non-plastic traits; i.e., constitutive traits). The first challenge is deciding upon the rearing conditions. Many biologists would prefer to quantify traits as they appear in nature, yet this method would confound species-level variation with environmental factors, including differences in temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and resources. Thus, investigators doing comparative work on plastic traits have assessed species under common-garden conditions to ensure that observed phenotypic differences can be attributed to genetic differences among species (Pigliucci et al. 1999, 2003, Colbourne 1997, Thaler and Karban 1997, Richardson 2001a-b, 2002a-b). One limitation is that species living under common-garden conditions might not exhibit the same magnitude of plasticity that they exhibit in nature. Given the extreme logistical difficulties of raising a large number of species under a wide range of environmental conditions, the common-garden approach is a necessary compromise that arises from the need to balance between these challenges. However, because temperature is one environmental condition of particular concern, we assessed the potential bias of temperature on plastic responses by rearing three of the species under two different temperatures.

The second challenge in taking a phylogenetic approach is to select populations that best represent a species. For most species, there is population-level variation in traits, especially in cosmopolitan species. However, comparative studies generally make the assumption that interspecific variation is larger than intraspecific variation. Because of the substantial challenge of assessing a large number of species, it is not feasible to sample multiple populations throughout each species’ range (although this is an interesting question that could be examined in future studies). To circumvent this problem, we attempted to minimize non-representative phenotypes by collecting species in their most common type of habitat and avoiding the collection of individuals from the extremes of a species’ range. However, we also assessed the impact of intraspecific variation on our conclusions by quantifying the plasticity of two distant populations from each of three cosmopolitan species (Lithobates catesbeianus, Anaxyrus americanus, and Hyla versicolor).

The experiments

All animals were collected as newly oviposited egg masses by the different laboratory groups from around the United States (Table A1). Once collected, eggs were transported back to the local laboratory and held at 21° C on a 12-hour light:dark cycle. Because the experiments were conducted in several laboratories around the United States, all laboratories used identical water mixtures (i.e., 20 L of de-ionized water mixed with 75 g of NaCl, 2.1 g of MgSO4, 1.05 g of KCl, 4.2 g of NaHCO3, and 2.8 g of CaCl).

Each egg-hatching experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design with three treatments and six replicates of each treatment for a total of 18 experimental units. The experimental units were Petri dishes (plastic 100 × 20 mm) containing 50 mL of water. To determine whether the embryos exhibited plastic responses to the three environments, we waited until the eggs approximately reached gastrulation stage (Gosner stage 12; Gosner 1960) and separated 190 eggs from each collection of clutches. In all experiments, we randomly assigned 10 eggs to each of the 18 Petri dishes and preserved an additional 10 eggs in buffered 10% formalin to confirm the developmental stage of the eggs at the start of each experiment. In one case (the Oregon population of Anaxyrus boreas), the eggs were collected at a slightly later stage (Gosner stage 15).

Our three treatments were control (i.e., no predator cues), crushed conspecific eggs, and crayfish-consumed conspecific eggs. The cues for each environment were generated using 1 L of water that had either no predator cues (i.e., control), eggs that were crushed by hand, or eggs that were consumed by a red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii). We chose a crayfish because as a group they are common consumers of amphibian eggs. We chose the red swamp crayfish in particular because it has a large native range in North America and an even larger introduced range (https://nas.er.usgs.gov/viewer/omap.aspx?SpeciesID=217). The implicit assumption is that the anti-predator responses induced by chemical cues of this crayfish would be similar to those induced by other crayfish that coexist with the various amphibian species. Unfortunately, there is probably no single egg predator species that coexists with every anuran species in North America.

For the crushed and consumed egg treatments, we used 3, 5, or 7 eggs to generate the cues, depending on egg size; the smaller the eggs of a given species, the more eggs were crushed or consumed to provide all species with an approximately equal amount of egg biomass that could produce chemical cues. This is important because the mass of prey fed to a predator affects the strength of the prey’s response (Schoeppner and Relyea 2008). To increase the likelihood that we would have a predator consume all eggs within 30 min, we set up three, 1-L crayfish containers; the container with the highest predation (i.e., usually consuming all eggs) was used for the cue source. All cues were added 30 min after being generated in the crushed and crayfish treatments. For both treatments, we removed a sample of the water containing the cues and avoided picking up any organic matter (e.g., pieces of destroyed eggs or feces from the crayfish). When adding the cues to the dishes, we removed 25 mL of water from each dish every 12 hrs and replaced it with 25 mL of new cue water. After the cues were added to the dishes, we added new water to the cue-generating containers to return their volume to 1 L.

As the embryos approached hatching, we checked the dishes every 4 hrs to determine the time of hatching (i.e., the time at which an individual successfully leaves its egg). As each animal hatched, we recorded the time to hatching and then euthanized and preserved the individual in buffered 10% formalin to later determine the Gosner stage and mass at hatching. Across all experiments, embryo survival ranged from 58–97% (median = 89%). At the end of the experiment, preserved hatchlings from all laboratories were shipped to the University of Pittsburgh where we quantified the mean Gosner stage at the start of each embryonic experiment, mean developmental stage at the time of hatching, and mean individual mass. Using these response variables, we calculated developmental rate (i.e., [stage at hatching-initial stage] ÷ time to hatching) and growth rate (i.e., mass at hatching ÷ time to hatching).

Additional experiments manipulating temperature

To assess the impact of different rearing temperatures on our conclusions, we examined the effects of different temperatures on the traits and trait plasticity of the embryos. To do this, we tested three of the species (one species from each family: A. americanus, H. versicolor, and L. clamitans) in identical experiments as described above, but at a second temperature (19 °C).

Statistical methods for assessing how each species responded to the environment

We assessed the plasticity of five traits for each species: mass, growth rate, time to hatching, stage at hatching, and development rate. We began by taking the mean of all individuals in an experimental unit for each response variable. In general, the mean time to hatching, growth rate, and developmental rate were all normally distributed; only the Anaxyrus fowleri was non-normally distributed, but non-parametric tests gave similar results as parametric tests. Because analysis of variance is robust to violations of this assumption, we used a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for each species followed by subsequent univariate tests for each response variable. Stage at hatching was generally non-normally distributed; moreover, 8 of the 23 species exhibited no variation in this trait, so this variable was removed from the MANOVA for these species (Table A3). All other data were rank-transformed. To test for trait induction due to an exposure to crushed or consumed eggs, we used planned contrasts between the control and crayfish treatments and between the control and crushed-conspecific treatments.

To determine if temperature interacted with plasticity for the three species that we raised at two temperatures, we used a MANOVA to test for effects of temperature, treatment, and their interaction. Response variables were generally normal within temperatures. All three species exhibited significant multivariate effects of temperature (Table A4) and one of the species exhibited a multivariate temperature-by-treatment interaction. However, this interaction was driven by a difference between responses to crayfish versus crushed eggs at the two different temperatures. Our interest was in examining plasticity in control versus crayfish and control versus crushed eggs and these specific plastic responses did not interact with temperature (all p > 0.19) for any of the traits in any of the three species. Because the magnitude of the plastic responses did not change as a function of the two temperatures, we used the data from the 21°C experiment to match all of the other species. While such results are encouraging, we cannot assess whether temperature might cause interactive effects on the magnitude of plasticity with the other species.

Statistical methods for quantifying trait plasticity

To address our questions about phylogenetic patterns of plasticity, we first had to determine how to quantify plasticity and how to interpret the outcomes when plasticity is quantified in different ways. We included measures of plasticity as an absolute measure (e.g., trait mean for the control treatment - trait mean for the crayfish treatment), plasticity that is proportional to the grand mean (e.g., [trait mean for the control treatment - trait mean for the crayfish treatment] ÷ grand mean), and plasticity that is proportional the pooled standard deviation, using the meta-analytic Hedge’s G (e.g., [trait mean for the control treatment - trait mean for the crayfish treatment] ÷ pooled standard deviation; Hedges 1981). These plasticity measures included both direction and magnitude. For the pooled standard deviations, we defined SD1 as the pooled standard deviation for the control and crushed environments and SD2 as the pooled standard deviation for the control and crayfish environments.

Given that some of our plasticity measures used the grand mean or a pooled standard deviation as a denominator, we also decided it was important to determine whether these denominators contained any phylogenetic signal that would cause a spurious result when we looked for a phylogenetic signal of plasticity. As a result, we assessed phylogenetic signal in the grand mean and in the pool standard deviations. In this way, when we assessed phylogenetic signal using plasticity metrics that included grand means and pooled standard deviations, we could assess the contribution of signal from both the numerator and denominator.

Phylogenetic comparative analyses

Species phylogenetic relationships were obtained from a published amphibian phylogeny (Pyron and Wiens 2013), pruned down to include only the species found in our study. Analyses with this tree were conducted using values averaged across populations to produce a species-level estimate when multiple populations were measured. Phylogenetic signal was quantified using Blomberg’s K (Blomberg et al. 2003). The statistical significance of phylogenetic signal was assessed using a randomization test described by Blomberg and Garland (2002) implemented in the R library picante (Kembel et al. 2010). Tests were performed using 10,000 randomizations. In all cases we consider p-values significant at values of ≤ 0.05. Our measurements of developmental stage included a few species that expressed zero plasticity. We calculated rate and signal for developmental stage plasticity both including and excluding species that exhibited zero plasticity and the results were quantitatively similar and qualitatively identical in both sets of analyses. As a result, we report results using all species.

For each trait and plasticity measure we compared the fits (i.e., AICc scores) of three models of continuous character evolution: (1) the Brownian motion (BM) model of character evolution which is based on models of random particle diffusion in a liquid, which is a widely used neutral model of character evolution under genetic drift and the model implicitly assumed by many phylogenetic comparative methods, (2) the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) model of character evolution (Hansen, 1997, Butler & King, 2004), which models character evolution as a random walk with a central tendency (i.e., a stabilizing force), and (3) the Early Burst (EB) model, which models character evolution as a random walk the rate of which decreases as you move from the root of the tree to the tips. Evolutionary rate was measured using sigma squared estimated from models fitted using the R package Geiger v 2.0.6 (Harmon et al. 2008, Pennell et al. 2014). For OU models we estimated α (i.e., the strength of attraction towards a central tendency), to evaluate the degree to which OU models differed from BM. We also estimated the phylogenetic half-life, which is a measure of how fast species would be expected to approach the evolutionary optimum.

The three models were first fitted using raw trait data and measures of plasticity. However, this produced rate estimates that were highly correlated with the order of magnitude of the range of trait variation (Fig. A2). For example, if one trait varied between 1 and 10 and another varied between 10 and 100, the latter trait would show a much higher rate estimate even though in proportion to their size both traits are likely evolving at similar rates. The typical method of dealing with this issue would be to estimate rates for log-transformed traits (Ackerly 2009). However, most of our measures of plasticity contained negative values for some species, which cannot be log transformed. Transforming the absolute values of trait plasticity was considered. However, this would have discarded information on the direction of plasticity, and would have greatly inflated rate estimates for trait plasticity that happened to show positive or negative values close to zero. Instead we divided all trait and trait plasticity values by the minimum value that any species exhibited, and used these ratio-transformed trait and trait plasticity values to estimate evolutionary rate. Like log-transformed traits, this yielded trait ranges that were wide when the maximum species trait values were multiples of minimum trait values, but that also preserved information on directionality. Only the results using ratio-transformed trait and plasticity values are reported here.

Results

Trait plasticity in each species

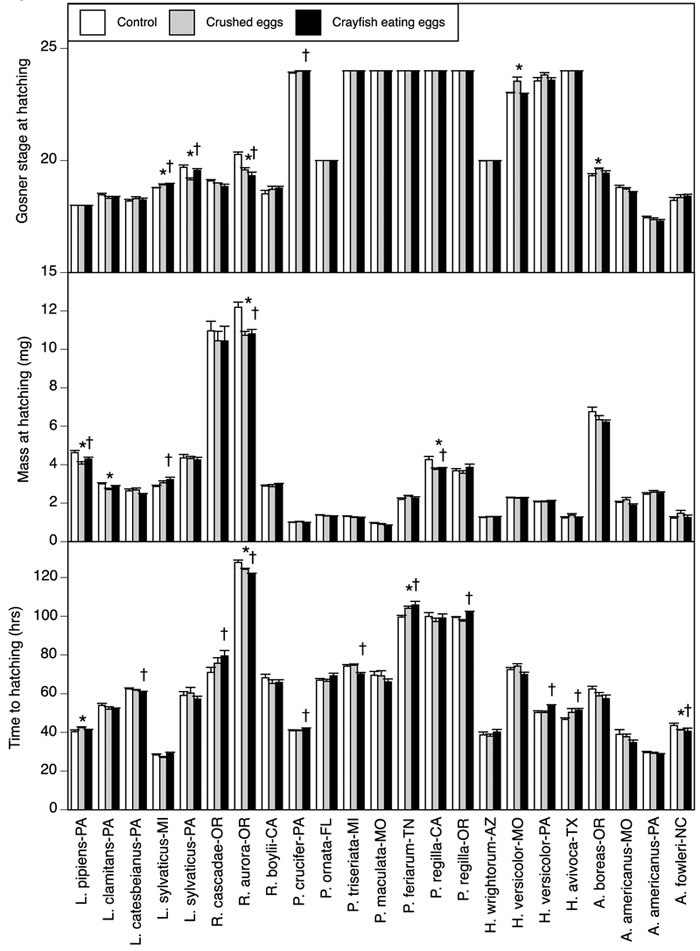

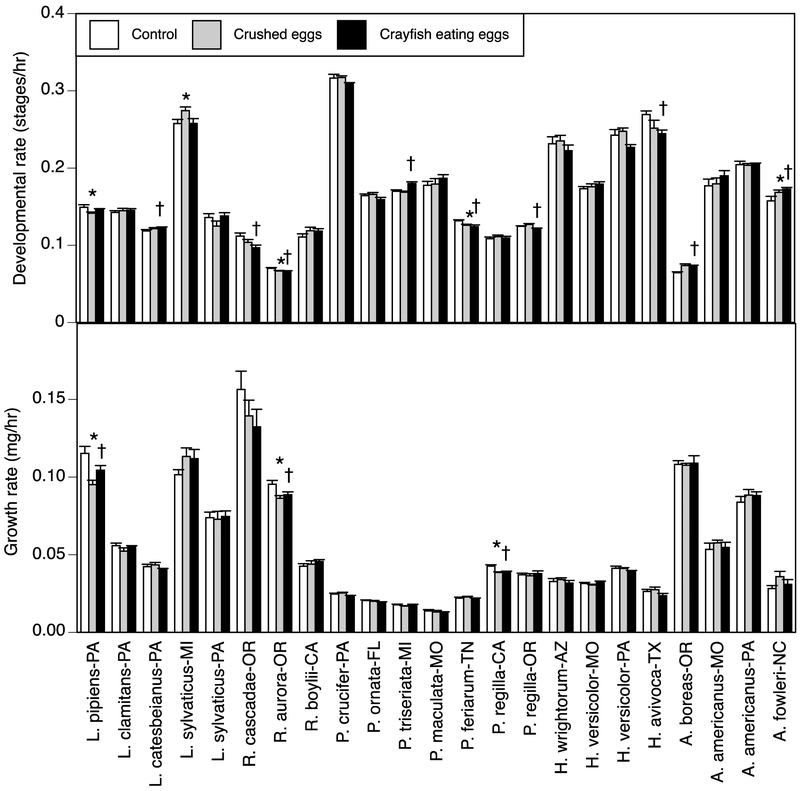

Our first analysis conducted MANOVAs on the five life history traits for each of the 23 experiments (Table A2; Figs. 1–2). Of the 23 experiments, nine had significant multivariate tests and one had a nearly significant multivariate test (i.e., p < 0.07).

Figure 1.

Time to hatching, mass at hatching, and Gosner stage at hatching for 20 species of amphibian embryos when exposed to cues from either no predator, crushed conspecific eggs, or crayfish consuming conspecific eggs. To test for population effects, three species were selected from two locations. Abbreviations refer to the states in which the animals were collected. Asterisks indicate species in which crushed-egg cues differed from the control; crosses indicate species in which crayfish cues differed from the control (p < 0.05). Data are means ± 1 SE.

Figure 2.

Growth rate (i.e., mass ÷ time to hatch) and developmental rate (i.e., Gosner stage ÷ time to hatch) for 20 species of amphibian embryos when exposed to cues from either no predator, crushed conspecific eggs, or crayfish consuming conspecific eggs. To test for population effects, three species were selected from two locations. Abbreviations refer to the states in which the animals were collected. Asterisks indicate species in which crushed-egg cues differed from the control; crosses indicate species in which crayfish cues differed from the control (p < 0.05). Data are means ± 1 SE.

We then examined the patterns of responses to crayfish consuming eggs versus the control, which should represent the highest risk environment. For time to hatching, four species hatched earlier with crayfish (p < 0.05), six species hatched later (p < 0.05), and the remaining 13 species exhibited no significant response. For mass at hatching, three species hatched at a smaller mass with crayfish, one species had a greater mass, and 20 species exhibited no response. For growth rate, three species grew at a slower rate with crayfish while the other 20 species exhibited no response. For stage at hatching, three species were less developed with crayfish, two species were more developed, and 18 species exhibited no response (including the eight species that exhibited zero variation in this trait). For developmental rate, five species had a slower developmental rate with crayfish, four species had a faster developmental rate, and 14 species exhibited no response.

Next, we examined the patterns of responses to crushed eggs versus the control (Table A2; Figs. 1–2). For time to hatching, two species hatched earlier with crushed eggs, two species hatched later, and the remaining 19 species exhibited no response. For mass at hatching, three species hatched at a smaller mass with crushed eggs, one species had a greater mass, and 19 species exhibited no response. For growth rate, three species grew at a slower rate with crushed eggs while the other 20 species exhibited no response. For stage at hatching, two species were less developed with crushed eggs, three species were more developed, and 18 species exhibited no response (including the eight species that exhibited zero variation in this trait). For developmental rate, two species had a slower developmental rate with crushed eggs, three species had a faster developmental rate, and 18 species exhibited no response.

Thermal sensitivity in plasticity among three focal species

For three of the species, we raised the embryos at two different temperatures to determine the importance of temperature in altering the traits and the plasticity of the traits (i.e., as determined by a treatment-by-temperature interaction; Table A3). For A. americanus and L. clamitans, temperature had a multivariate effect that was driven by four of the five embryo traits, but temperature did not alter the magnitudes of plasticity. For H. versicolor, however, there were multivariate effects of temperature, treatment, and their interaction. The interaction was driven by the mass at hatching and stage at hatching. However, subsequent analyses indicated that contrasts of interest (i.e., the magnitude of plasticity for the control versus crushed-egg treatments and the magnitude of plasticity for the control versus consumed-egg treatments) did not differ with temperature.

Phylogenetic signal in traits

Our analysis of phylogenetic signal began by testing for phylogenetic signal in the five embryonic traits within each of the three environments (control, crayfish cues, and crushed-egg cues; Tables 1–5, A4-A8). Time to hatching did not exhibit statistically significant phylogenetic signal in any environment. Mass at hatching, stage at hatching, and growth rate all exhibited significant phylogenetic signal in all three environments. Development rate exhibited significant phylogenetic signal in two environments and nearly significant (p = 0.054) in the third. Across all 15 analyses of phylogenetic signal in embryonic traits, phylogenetic signal was significant in 73% of the tests (Table 6).

Table 1.

Tests of phylogenetic signal and evolutionary rates for time to hatching of amphibian embryos when raised in three inducing environments. The analyses tested A) traits and B) trait plasticity of the embryos. To better understand how phylogenetic signal was affected by the numerators and denominators in the plasticity estimates, we also assessed phylogenetic signal in the C) grand mean and pooled standard deviations. Phylogenetic signal was tested using Blomberg’s K and its associated P value (bold font indicates significant tests; p < 0.05). Three models of continuous character evolution were used to determine which model produced the best fit to the data (based on AICc scores): Brownian Motion (BM), Ornstein Uhlenbeck (OU), and Early Burst (EB). Models with the lowest AICc values are shown in bold font.

| A. Trait | Blomberg’s K | P-value | BM AICc | OU AICc | EB AICc |

| Control | 0.339 | 0.076 | 49.4 | 45.1 | 52.2 |

| Crushed-egg cues | 0.338 | 0.082 | 50.2 | 45.6 | 53.1 |

| Crayfish cues | 0.313 | 0.116 | 54.0 | 48.6 | 56.9 |

| B. Trait plasticity | |||||

| (Control - Crushed) | 0.189 | 0.417 | 49.3 | 35.4 | 52.2 |

| (Control – Crayfish) | 0.131 | 0.700 | 49.9 | 30.0 | 52.8 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Grand mean | 0.186 | 0.421 | 49.4 | 35.3 | 52.2 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Grand mean | 0.170 | 0.488 | 49.5 | 34.2 | 52.4 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Pooled SD1 | 0.197 | 0.393 | 43.7 | 30.2 | 46.5 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Pooled SD2 | 0.135 | 0.676 | 61.0 | 41.6 | 63.8 |

| C. Grand mean & pooled SD | |||||

| Grand mean | 0.331 | 0.092 | 51.0 | 46.3 | 53.9 |

| Pooled SD1 | 0.186 | 0.437 | 86.1 | 73.1 | 89.0 |

| Pooled SD2 | 0.261 | 0.215 | 77.1 | 70.2 | 80.0 |

Table 5.

Tests of phylogenetic signal and evolutionary rates for developmental rate of amphibian embryos when raised in three inducing environments. The analyses tested A) traits and B) trait plasticity of the embryos. To better understand how phylogenetic signal was affected by the numerators and denominators in the plasticity estimates, we also assessed phylogenetic signal in the C) grand mean and pooled standard deviations. Phylogenetic signal was tested using Blomberg’s K and its associated P value (bold font indicates significant tests; p < 0.05). Three models of continuous character evolution were used to determine which model produced the best fit to the data (based on AICc scores): Brownian Motion (BM), Ornstein Uhlenbeck (OU), and Early Burst (EB). Models with the lowest AICc values are shown in bold font.

| A. Trait | Blomberg’s K | P-value | BM AICc | OU AICc | EB AICc |

| Control | 0.353 | 0.054 | 61.6 | 57.7 | 64.5 |

| Crushed-egg cues | 0.422 | 0.017 | 56.1 | 54.1 | 58.9 |

| Crayfish cues | 0.374 | 0.037 | 57.9 | 54.7 | 60.7 |

| B. Trait plasticity | |||||

| (Control - Crushed) | 0.076 | 0.954 | 71.6 | 41.2 | 74.4 |

| (Control – Crayfish) | 0.131 | 0.713 | 62.9 | 42.7 | 65.8 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Grand mean | 0.178 | 0.490 | 38.3 | 24.1 | 41.2 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Grand mean | 0.191 | 0.386 | 52.9 | 40.1 | 55.8 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Pooled SD1 | 0.193 | 0.399 | 42.3 | 29.6 | 45.1 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Pooled SD2 | 0.113 | 0.818 | 65.1 | 42.5 | 68.0 |

| C. Grand mean & pooled SD | |||||

| Grand mean | 0.384 | 0.029 | 57.2 | 54.3 | 60.1 |

| Pooled SD1 | 0.190 | 0.388 | 94.1 | 80.8 | 97.0 |

| Pooled SD2 | 0.312 | 0.089 | 81.9 | 76.6 | 84.7 |

Table 6.

A summary of the analyses for significant phylogenetic signal (Blomberg’s K) in the A) traits and B) trait plasticity of amphibian embryos exposed to predatory cues (√ = p < 0.05). Detailed statistics can be found in Tables 1-5. To better understand how phylogenetic signal was affected by the numerators and denominators of several of the plasticity estimates, we also assessed phylogenetic signal in the C) grand means [GM] and pooled standard deviations [SD1 and SD2].

| Time to hatching | Mass at hatching | Stage at hatching | Growth rate | Development rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Trait | |||||

| Control | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Crush | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Crayfish | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| B. Trait plasticity | |||||

| Control-Crushed | √ | √ | |||

| Control-Crayfish | √ | √ | |||

| (Control-Crushed) ÷ GM | |||||

| (Control-Crayfish) ÷ GM | |||||

| (Control-Crushed) ÷ SD1 | √ | ||||

| (Control-Crayfish) ÷ SD2 | |||||

| C. Grand mean & pooled SDs | |||||

| GM | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| SD1 (Control, Crushed) | √ | √ | |||

| SD2 (Control, Crayfish) | |||||

Phylogenetic signal in trait plasticity

We next tested for phylogenetic signal in the plasticity of the five embryonic traits using multiple measures of plasticity (Tables 1–5, A4-A8). For time to hatching and developmental rate, none of the six tests exhibited significant phylogenetic signal. For mass at hatching and growth rate, two of the six measures of plasticity (Control – Crushed and Control – Crayfish) exhibited significant signal. For stage at hatching, only one of the six measures ([Control – Crushed]/SD1) exhibited significant signal. Across all 30 analyses of phylogenetic signal in trait plasticity, phylogenetic signal was significant in 17% of the tests (Table 6).

Models of trait evolution and evolutionary rates of traits versus trait plasticity

For time to hatching and developmental rate, the OU model was a better fit for both traits and their plasticity. For the other three traits, the OU model was essentially tied with BM, with comparisons of the two models exhibiting delta AICc scores of less than two. It is notable that the best fitting model of trait evolution was always the same for both trait means and plasticity measures derived from them for any given life history trait. Values of α estimated for OU models in cases where the OU model was a better fit were higher than those estimated in cases where BM was a better fit (Table 7). For time to hatching and developmental rate, plasticity tended to show a higher evolutionary rate than trait means under the best fitting (i.e., OU) model of character evolution. For stage at hatching, plasticity showed a higher evolutionary rates than trait means regardless of whether sigma squared was estimated using a BM or OU model. For mass at hatching and growth rate, the opposite held true; plasticity tended to show a lower evolutionary rate than trait means. We note that the evolutionary rates for the pooled SD generally showed a greatly inflated evolutionary rate, but the method employed to measure evolutionary rates was designed for species trait means, not standard deviations.

Table 7.

Rate parameters estimated for Ornstein Uhlenbeck (OU) models of character evolution. Alpha (α) is the attraction strength of the evolutionary optimum, phylogenetic half-life (PHL) is a measure of how fast species would be expected to approach the evolutionary optimum. Values of α in bold indicate instances where the OU model had the lowest AICc score of the three models that were considered.

| Time to Hatching |

Mass at Hatching |

Developmental Stage |

Growth Rate |

Developmental Rate |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Trait | α | PHL | α | PHL | α | PHL | α | PHL | α | PHL |

| Control | 0.038402 | 18.04998 | 0.008496 | 81.58278 | 0.008088 | 85.69541 | 0.015307 | 45.28156 | 0.030426 | 22.7814 |

| Crushed-egg cues | 0.038994 | 17.77575 | 0.008725 | 79.43983 | 0.006898 | 100.4809 | 0.015495 | 44.73403 | 0.023369 | 29.66099 |

| Crayfish cues | 0.044294 | 15.64887 | 0.008853 | 78.29554 | 0.007496 | 92.47209 | 0.016042 | 43.20755 | 0.027609 | 25.10627 |

| B. Trait plasticity | ||||||||||

| (Control - Crushed) | 0.132396 | 5.235418 | 0.020449 | 33.89608 | 2.713433 | 0.25545 | 0.007647 | 90.64628 | 2.718282 | 0.254995 |

| (Control – Crayfish) | 0.460493 | 1.50523 | 0.019438 | 35.65952 | 0.057431 | 12.06922 | 0.01821 | 38.06354 | 0.24012 | 2.886666 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Grand mean | 0.150743 | 4.598212 | 0.183382 | 3.77979 | 1.11786 | 0.620066 | 0.112611 | 6.155223 | 2.718282 | 0.254995 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Grand mean | 0.195834 | 3.539464 | 0.264430 | 2.621291 | 0.689952 | 1.004631 | 0.140089 | 4.947922 | 0.239441 | 2.894854 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Pooled SD1 | 0.111275 | 6.229152 | 0.142578 | 4.861535 | 0.01573 | 44.06521 | 0.120524 | 5.751136 | 2.718282 | 0.254995 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Pooled SD2 | 0.316571 | 2.189548 | 0.182090 | 3.806622 | 1.293636 | 0.535813 | 0.040656 | 17.04901 | 0.740391 | 0.936191 |

| C. Grand mean & pooled SD | ||||||||||

| Grand mean | 0.039922 | 17.36265 | 0.008636 | 80.25789 | 0.007356 | 94.23198 | 0.015592 | 44.45448 | 0.026646 | 26.01362 |

| Pooled SD1 | 2.718282 | 0.254995 | 0.012946 | 53.54256 | 0.220752 | 3.139933 | 0.01567 | 44.23534 | 0.15818 | 4.382019 |

| Pooled SD2 | 0.081241 | 8.531972 | 0.017354 | 39.94223 | NA | NA | 0.020833 | 33.27169 | 0.043694 | 15.86359 |

Discussion

In documenting the life history responses to predator cues in three families of amphibians, we discovered that responses varied a great deal among species. Moreover, we found that the traits frequently exhibited phylogenetic signal whereas trait plasticity rarely exhibited phylogenetic signal. Finally, we discovered that evolutionary rates were more rapid for traits than trait plasticity for two life history traits, but less rapid for three life history traits. Below we expand on each of these discoveries.

The phenotypic responses of embryos compared to the literature

More than 30 embryonic plasticity studies have been conducted with amphibians over the past two decades to quantify their life history responses to predators under a variety of experimental conditions (Segev et al. 2015). These studies have found a range of predator-induced responses that suggest that different species have evolved different magnitudes of embryonic responses to egg predators, damaged eggs, and larval predators (including a complete lack of response). However, a major challenge in interpreting the patterns of induced responses among species is that nearly all of these studies have examined one species at a time, although a few have examined two species. The power of the current study’s approach is that all 20 species were raised under identical conditions with the same suite of environmental manipulations, making it possible to attribute differences in response to the species and not differences in experimental design (see also Gomez-Mestre et al. 2008). However, as noted earlier, an important constraint in doing large comparisons among species raised under identical conditions is that it becomes difficult or impossible to know whether the fundamental conclusions would change under different abiotic conditions including differences in temperature, pH, and per capita food rations. This constraint also applies to comparing all past studies that have raised one or more species under controlled conditions, whether in the laboratory or in outdoor venues.

In regard to the time it takes for an embryo to hatch, one would predict an adaptive response to egg predators would be for embryos to hatch sooner and avoid the predator, although this would likely come at the cost of reduced growth and development of the newly hatched animal. Consistent with this prediction, a number of studies have observed earlier hatching times (e.g., Johnson et al. 2003, Touchon et al. 2006, Segev et al. 2015), but a substantial number of studies have not (e.g., Schalk et al. 2002, Anderson and Petranka 2003, Dibble et al. 2009). Similarly, even when cues from egg predators induce earlier hatching, the expected trade-off of smaller, less developed hatchlings sometimes is observed (Johnson et al. 2003, Gomez-Mestre et al. 2008), but many times the response variables are simply not measured. In our experiments, however, there was not evidence of a consistent tradeoff; several species that were induced to exhibit significantly shorter or longer times to hatching did not exhibit significant changes in their mass at hatching or stage at hatching. Of course, a number of constraints could prevent such a response from evolving.

In our set of 23 experiments, embryos exposed to crayfish induced earlier time to hatching in four experiments, a later time to hatching in six experiments, and no change in 13 experiments. For comparison, there have been three studies of amphibian embryos raised with and without crayfish cues and all of them have observed earlier times to hatching with crayfish cues (using L. sphenocephala and L. clamitans; Johnson et al. 2003, Saenz et al. 2003, Anderson & Brown 2009). In our study, L. clamitans also tended to hatch earlier as well, but the difference was not significantly different from the control (P = 0.19). We have no way of assessing potential publication bias in which studies may have observed no response to crayfish cues and not published the results. Of course, one would not expect every species to respond to a given predator in the same way (Relyea 2007) and plastic responses may depend on a wide variety of factors including abiotic conditions, ontogeny, and whether the predators consumes both eggs and larvae of amphibians (as crayfish can do). As noted earlier, one of the challenges in exposing a large number of species from across an entire continent to cues from a single predator species is that not every species will coexist with the predator (although it may coexist with close relatives of the predator). As a result, an important caveat to the results of the crayfish cue treatment is that we may have some cases of species not responding to the cue because that do not coexist with the species of crayfish that we used. One implication of this is that the more reliable data may be how the embryos respond to the cues of crushed eggs.

We also observed that embryos exposed to crushed eggs induced earlier time to hatching in two experiments, a later time to hatching in two experiments, and no change in 19 experiments. We only found two studies that have examined amphibian embryo responses to damaged eggs; one study observed the induction of earlier hatching (Chiromantis hansenae; Poo & Bickford 2014) whereas the other study observed no effect (L. temporaria; Mandrillon & Saglio 2007). Collectively, these results suggest that amphibian embryos often respond to cues from crayfish eating conspecific eggs and occasionally respond to cues from damaged conspecific eggs.

Phylogenetic signal in traits and trait plasticity

We observed a striking consistency in the occurrence of phylogenetic signal in the life history traits. Four of the five sets of life history trait means showed significant signal, and even time to hatching showed levels of signal that could be described as “nearly significant” with p-values of less than 0.1 for two of the three trait means. Detecting phylogenetic signal in the life history traits of a group of species is not particularly surprising. Such patterns have been detected in a wide range of taxa including arboreal-nesting amphibians (Gomez-Mestre et al. 2008), lizards (Brandt and Navas 2011), carabid beetles (Sota & Ishikawa 2004), and plants (Moles et al. 2005).

The more interesting question for the current study is whether there is phylogenetic signal in trait plasticity. One of the most striking discoveries was how rarely trait plasticity exhibited phylogenetic signal across the five life history variables. From our 30 assessments of phylogenetic signal in life history traits, only 17% exhibited significant phylogenetic signal. Phylogenetic signal was completely lacking for time to hatching whereas it was only present in 17–33% of the six comparisons within each type of trait. To evaluate the robustness of our results, we used three metrics: 1) the difference in phenotypic value expressed in two treatments, 2) the difference in phenotypic value divided by the grand mean, and 3) the difference in phenotypic value divided by a pooled standard deviation. Signal was present much more often when plasticity was measured as a simple difference (40% of comparisons) than when measured as a ratio (5% of comparisons in which the difference was divided by a grand mean or pooled standard deviation). In this single case of a significant ratio ([Control-Crushed/SD1] for developmental stage), neither the numerator or denominator showed significant signal.

Studies of phylogenetic signal in plastic traits have been relatively rare. Whereas there are studies comparing the plasticity of a few species (e.g., Cook 1968, Day 1994, Smith and Van Buskirk 1995, Murren et al. 2015), studies containing a large number of species are less common, likely as a result of the challenge of conducting a large number of induction experiments. Of those studies that have been done, some have focused on testing the theoretical prediction that greater environmental heterogeneity is associated with greater amounts of plasticity by using phylogenetic contrasts (Van Buskirk 2002). Others have created phylogenies and mapped presence or absence of plasticity as a discrete trait onto the trees (Colbourne et al. 1997). In these cases, there do appear to be significant differences among major clades. Although these studies performed no explicit test for phylogenetic signal, it seems that phylogenetic signal likely existed. Examples include predator-induced morphological defenses in 34 species of zooplankton (Daphnia; Colbourne et al. 1997) and herbivore-induced defenses among 21 species of cotton (Gossypium; Thaler and Karban 1997). Finally, some studies have mapped different magnitudes of trait plasticity onto a phylogeny, but still not tested for significant phylogenetic signal. Most of these studies were focused on other research questions that simply needed phylogenetically corrected analyses. Examples include shade-induced and day-length induced traits in six to nine species/populations of Arabidopsis thaliana (Pigliucci et al. 1999, Pollard et al. 2001) and temperature-induced changes in the larval period and morphology among 13 species of adult frogs (Gomez-Mestre and Buchholz 2006).

Evolutionary models and rates of traits versus trait plasticity

For every life history trait the OU model was either the best fitting model of character evolution or tied with BM based on AICc scores. The most common interpretation of the OU model is that it represents stabilizing selection due to the presence of adaptive optima (Butler et al. 2004, Beaulieu et al. 2012). The prominence of the OU model in our model fits may indicate that both traits and their plasticity tend to exhibit an adaptive optimum. We note, however, that in cases where α, the force of evolutionary attraction to an evolutionary optimum, is small behavior of an OU model may be little different from BM (Cooper et al. 2016). Following the recommendation of Cooper et al. (2016), we used α to calculate “evolutionary half-life” (Hansen 1997) of each OU model in this study. This parameter does not have a strict biological interpretation, but Cooper et al (2016) suggest that when it is large compared to the root age of a tree that it is estimated from it reflects a mode of evolution that is more similar to BM than the OU model. Our results confirm that in cases where the OU model was a better fit than BM, that values of α were also large resulting in estimates of evolutionary half-life much less than the root age of the phylogeny that we used in our study (Table A9). The EB model always showed the worst fit of the three models considered, indicating that evolutionary rates do not appear to be decreasing over time. This is in sharp contrast to what was found in studies of all mammals (Cooper et al. 2010) and birds (Brusatte et al. 2014), but similar to the results that Harmon et al. (2010) obtained when they examined smaller clades of animals.

We also examined the evolutionary rate of the traits versus the plasticity of the traits using ratio-transformed traits, which yielded rate measures that generally differed by less than an order of magnitude. This is similar to the level of rate variation that Ackerly (2009) saw across plant traits (i.e., roughly two orders of magnitude) and that Rabosky and Adams (2012) observed among different clades for body mass. Based on these results, we suggest that ratio-transformed data, rather than raw or log-transformed data, should generally be used to compare the evolutionary rates of traits to trait plasticity, and when comparing rates among different measures of plasticity. Ratio transformation might also prove useful in general when calculating rates for traits that are not lognormal, or comparing the rates of lognormal and non-lognormal traits.

When we compared the evolutionary rate of traits versus trait plasticity using ratio transformation, the evolutionary rates of trait plasticity were greater than that of the traits from which they were calculated for three traits (time to hatching, developmental stage, and developmental rate) and slower for two life history traits (mass at hatching and growth rate). This could be due to differences in the fitness consequence of phenotypic shifts in the direction or magnitude of plasticity compared to that of the traits themselves, or due to differences in the genetic architecture of traits and trait plasticity. Regardless, it seems that evolutionary responses of life history traits to environmental changes or other selective pressures that push traits beyond or in opposition to their normal plasticity range could potentially happen more quickly through shifts in either trait means or through shifts in trait plasticity somewhat idiosyncratically depending upon the trait considered.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate that plastic responses to environmental variation can be highly species-specific, which is not particularly surprising. More importantly, the traits that species possess consistently exhibit phylogenetic signal, yet the plasticity of those traits rarely exhibits phylogenetic signal. In addition, the OU model was either the best fitting model of character evolution or tied with BM for traits and all measures of trait plasticity, perhaps indicating the presence of adaptive peaks. Finally, whether trait plasticity evolves more slowly or faster than trait means varies depending upon the trait considered. Given the paucity of large studies that examine phylogenetic patterns in plasticity, it remains to be seen whether the patterns exhibited by amphibian embryos are representative of other taxa.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Tests of phylogenetic signal and evolutionary rates for mass at hatching of amphibian embryos when raised in three inducing environments. The analyses tested A) traits and B) trait plasticity of the embryos. To better understand how phylogenetic signal was affected by the numerators and denominators in the plasticity estimates, we also assessed phylogenetic signal in the C) grand mean and pooled standard deviations. Phylogenetic signal was tested using Blomberg’s K and its associated P value (bold font indicates significant tests; p < 0.05). Three models of continuous character evolution were used to determine which model produced the best fit to the data (based on AICc scores): Brownian Motion (BM), Ornstein Uhlenbeck (OU), and Early Burst (EB). Models with the lowest AICc values are shown in bold font.

| A. Trait | Blomberg’s K | P-value | BM AICc | OU AICc | EB AICc |

| Control | 0.737 | 0.003 | 94.6 | 96.6 | 97.4 |

| Crushed-egg cues | 0.730 | 0.004 | 92.6 | 94.5 | 95.4 |

| Crayfish cues | 0.733 | 0.003 | 96.2 | 98.0 | 99.0 |

| B. Trait plasticity | |||||

| (Control - Crushed) | 0.473 | 0.028 | 72.5 | 71.8 | 75.4 |

| (Control – Crayfish) | 0.485 | 0.037 | 93.2 | 93.3 | 96.1 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Grand mean | 0.160 | 0.566 | 44.7 | 28.2 | 47.6 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Grand mean | 0.179 | 0.428 | 77.3 | 63.5 | 80.1 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Pooled SD1 | 0.221 | 0.288 | 65.9 | 55.4 | 68.8 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Pooled SD2 | 0.228 | 0.251 | 62.3 | 53.1 | 65.2 |

| C. Grand mean & pooled SD | |||||

| Grand mean | 0.735 | 0.003 | 94.4 | 96.3 | 97.2 |

| Pooled SD1 | 0.605 | 0.008 | 131.1 | 132.3 | 134.0 |

| Pooled SD2 | 0.501 | 0.058 | 150.4 | 150.6 | 153.3 |

Table 3.

Tests of phylogenetic signal and evolutionary rates for developmental stage to hatching of amphibian embryos when raised in three inducing environments. The analyses tested A) traits and B) trait plasticity of the embryos. To better understand how phylogenetic signal was affected by the numerators and denominators in the plasticity estimates, we also assessed phylogenetic signal in the C) grand mean and pooled standard deviations. Phylogenetic signal was tested using Blomberg’s K and its associated P value (bold font indicates significant tests; p < 0.05). Three models of continuous character evolution were used to determine which model produced the best fit to the data (based on AICc scores): Brownian Motion (BM), Ornstein Uhlenbeck (OU), and Early Burst (EB). Models with the lowest AICc values are shown in bold font. (NE = not estimable due to a denominator of zero).

| A. Trait | Blomberg’s K | P-value | BM AICc | OU AICc | EB AICc |

| Control | 1.079 | 0.000 | −32.1 | −30.4 | −29.3 |

| Crushed-egg cues | 1.167 | 0.000 | −33.2 | −31.2 | −30.3 |

| Crayfish cues | 1.131 | 0.001 | −32.4 | −30.6 | −29.6 |

| B. Trait plasticity | |||||

| (Control - Crushed) | 0.173 | 0.547 | 52.9 | 38.6 | 55.8 |

| (Control – Crayfish) | 0.260 | 0.473 | 67.5 | 60.9 | 70.3 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Grand mean | 0.197 | 0.492 | 56.5 | 44.7 | 59.4 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Grand mean | 0.251 | 0.483 | 66.3 | 59.1 | 69.2 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Pooled SD1 | 0.479 | 0.014 | 12.9 | 13.5 | 15.8 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Pooled SD2 | 0.234 | 0.333 | 56.3 | 47.7 | 59.2 |

| C. Grand mean & pooled SD | |||||

| Grand mean | 1.135 | 0.000 | −32.8 | −30.9 | −30.0 |

| Pooled SD1 | 0.226 | 0.279 | 32.1 | 22.2 | 35.0 |

| Pooled SD2 | 0.317 | 0.086 | NE | NE | NE |

Table 4.

Tests of phylogenetic signal and evolutionary rates for growth rate of amphibian embryos when raised in three inducing environments. The analyses tested A) traits and B) trait plasticity of the embryos. To better understand how phylogenetic signal was affected by the numerators and denominators in the plasticity estimates, we also assessed phylogenetic signal in the C) grand mean and pooled standard deviations. Phylogenetic signal was tested using Blomberg’s K and its associated P value (bold font indicates significant tests; p < 0.05). Three models of continuous character evolution were used to determine which model produced the best fit to the data (based on AICc scores): Brownian Motion (BM), Ornstein Uhlenbeck (OU), and Early Burst (EB). Models with the lowest AICc values are shown in bold font.

| A. Trait | Blomberg’s K | P-value | BM AICc | OU AICc | EB AICc |

| Control | 0.5948 | 0.0069 | 94.2 | 93.9 | 97.0 |

| Crushed-egg cues | 0.6049 | 0.0069 | 91.4 | 91.1 | 94.3 |

| Crayfish cues | 0.5863 | 0.0079 | 94.3 | 93.6 | 97.1 |

| B. Trait plasticity | |||||

| (Control - Crushed) | 0.6188 | 0.0061 | 46.9 | 49.2 | 49.7 |

| (Control – Crayfish) | 0.4755 | 0.0306 | 60.8 | 61.3 | 63.6 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Grand mean | 0.2175 | 0.3597 | 33.0 | 22.0 | 35.8 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Grand mean | 0.2106 | 0.3055 | 60.5 | 49.5 | 63.4 |

| (Control - Crushed) ÷ Pooled SD1 | 0.2355 | 0.2500 | 59.7 | 50.7 | 62.5 |

| (Control - Crayfish) ÷ Pooled SD2 | 0.3230 | 0.0643 | 52.7 | 48.6 | 55.5 |

| C. Grand mean & pooled SD | |||||

| Grand mean | 0.5961 | 0.0075 | 93.2 | 92.8 | 96.0 |

| Pooled SD1 | 0.5325 | 0.0304 | 133.7 | 134.0 | 136.6 |

| Pooled SD2 | 0.4715 | 0.0506 | 129.8 | 129.0 | 132.6 |

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a National Science Foundation grant (DEB 07–16149) to RAR and PRS. During the data analysis, JIH was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant K12GM088021. Content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of either the NIH or NSF. We were also assisted by a large number of undergraduate students spanning all of the laboratories. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. We also thanks the Associate Editor and three excellent reviewers for their help in making this a stronger, clearer, and more compelling publication.

Literature cited

- Ackerly David. 2009. Conservatism and diversification of plant functional traits: evolutionary rates versus phylogenetic signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:19699–19706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, and Brown WD. 2009. Plasticity of hatching in green frogs (Rana clamitans) to both egg and tadpole predators. Herpetologica 65:207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AR and Petranka JW. 2003. Odonate predator does not affect hatching time or morphology of two amphibians. J Herpetol 37:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Jhwueng DC, Boettiger C, and O’Meara BC. 2012. Modeling stabilizing selection: expanding the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck model of adaptive evolution. Evolution 66:2369–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendonk TU, Barraclough TG, and Barraclough JC. 2003. Phylogenetics of pond and lake lifestyles in Chaoborus midge larvae. Evolution 57:2173–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg SP, Garland T Jr., and Ives AR. 2003. Testing for phylogenetic signal in comparative data: behavioral traits are more labile. Evolution 57:717–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma M, Spaak P, and De Meester L. 1998. Predator-mediated plasticity in morphology, life history, and behavior of Daphnia: uncoupling of responses. Am Nat 152:237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R and Navas CA. 2011. Life history evolution on tropidurinae lizards: Influence of lineage, climate, and body size. PLoS ONE 6:e20040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusatte SL, Lloyd GT, Wang SC, and Norell MA. 2014. Gradual assembly of avian body plan culminated in rapid rates of evolution across the dinosaur-bird transition. Current Biol 24:2386–2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JH, and Strauss SY. 2012. Effects of competition on phylogenetic signal and phenotypic plasticity in plant functional traits. Ecology 93:S126–S137. [Google Scholar]

- Butler MA, and King AA. 2004. Phylogenetic comparative analysis: a modeling approach for adaptive evolution. Am Nat 164:683–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadle JE, and Greene HW. 1993. Phylogenetic patterns, biogeography, and the ecological structure of neotropical snake assemblages Pages 281–293 in Ricklefs RE and Schluter D, eds. Species Diversity in Ecological Communities: Historical and Geographical Perspectives. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan HSH Maughan UK Steiner. 2008. Phenotypic plasticity, costs of phenotypes, and costs of plasticity. Annals NY Acad Sci 1133:44–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers DP, Kiesecker JM, Marco A, DeVito J, Anderson MT, and Blaustein AR. 2001. Predator-induced life history changes in amphibians: egg predation induces hatching. Oikos 92:135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Colbourne JK, Hebert PDN, and Taylor DJ. 1997. Evolutionary origins of phenotypic diversity in Daphnia Pages 163–188 in Givnish TJ and Sytsma KJ, eds. Molecular Evolution and Adaptive Radiation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Cook CDK 1968. Phenotypic plasticity with particular reference to three amphibious plant species Pages 97–111 in Heywood VH, ed. Modern Methods in Plant Taxonomy. Academic Press, London. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper N, and Purvis A. 2010. Body size evolution in mammals: complexity in tempo and mode. Am Nat 175:727–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper N, Thomas GH, and FitzJohn RG. 2016. Shedding light on the ‘dark side’ of phylogenetic comparative methods. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7:693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day T, Pritchard J, and Schluter D. 1994. A comparison of two sticklebacks. Evolution 48:1723–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt TJ, and Scheiner SM. 2004. Phenotypic Plasticity: Functional and Conceptual Approaches. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Dibble CJ, Kauffman JE, Zuzik EM, Smith GR, and Rettig JE, 2009. Effects of potential predator and competitor cues and sibship on wood frog (Rana sylvatica) embryos. Amphibia-Reptilia 30:294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PK 2002. A developmental morphologist’s perspective on plasticity. Evol Ecol 16:267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Doughty P 1995. Testing the ecological correlates of phenotypically plastic traits within a phylogenetic framework. Acta Oecol 16:519–524. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J 2004. Inferring Phylogenies. Sinauer Associates, Sutherland, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Mestre I, and Buchholz D. 2006. Developmental plasticity mirrors differences among taxa in spadefoot toads linking plasticity and diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:19021–19026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Mestre IJJ Wiens, and Warkentin KM. 2008. Evolution of adaptive plasticity: Risk-sensitive hatching in Neotropical leaf-breeding treefrogs. Ecol Monogr 78:205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Gosner KL 1960. A simplified table for staging anuran embryos and larvae with notes on identification. Herpetologica 16: 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Grant PR 1986. Ecology and Evolution of Darwin’s Finches. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon LJ, Losos JB, Davies TJ, Gillespie GC, Gittleman JL, Jennings WB, Kozak KH, McPeek MA, Moreno‐Roark F, Near TJ, and Purvis A. 2010. Early bursts of body size and shape evolution are rare in comparative data. Evolution 64:2385–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon LJ, Weir JT, Brock CD, Glor RE, and Challenger W. 2008. GEIGER: investigating evolutionary radiations. Bioinformatics 24:129–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PH, and Pagel MD. 1991. The Comparative Method in Evolutionary Biology Oxford Univ. Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV 1981. Distribution theory for Glass’ estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Edu Stat 6:107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegg S, Brinkmann H, and Meyer A. 2004. Phylogeny and comparative substitution rates of frogs inferred from sequences of three nuclear genes. Mol Biol Evol 21:1188–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JB, Saenz D, Adams CK, and Conner RN. 2003. The influence of predator threat on the timing of a life history switch point: Predator-induced hatching in the southern leopard frog (Rana sphenocephala). Can J Zool 81:1608–1613. [Google Scholar]

- Kembel SW, Cowan PD, Helmus MR, Cornwell WK, Morlon H, Ackerly DD, Blomberg SP, and Webb CO. 2010. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 26:1463–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurila A, Crochet P-A, and Merilä J. 2001. Predation-induced effects on hatching morphology in the common frog (Rana temporaria). Can J Zool 79:926–930. [Google Scholar]

- Laurila A, Pakkasmaa S, Crochet PA, and Merila J. 2002. Predator-induced plasticity in early life history and morphology in two anuran amphibians. Oecologia 132:524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losos JB 1990. A phylogenetic analysis of character displacement in Caribbean Anolis communities. Evolution 44:558–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losos JB 2008. Phylogenetic niche conservatism, phylogenetic signal and the relationship between phylogenetic relatedness and ecological similarity among species. Ecol Let 11:995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losos JB, Jackman TR, Larson A, de Queiroz K, and Rodriguez-Schettino L. 1998. Contingency and determinism in replicated adaptive radiations of island lizards. Science 279:2115–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrillon A-L, and Saglio P. 2007. Effects of embryonic exposure to conspecific chemical cues on hatching and larval traits in the common frog (Rana temporaria). Chemoecology 17: 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPeek MA, and Brown JM. 2000. Building a regional species pool: Diversification of the Enallagma damselflies in eastern North American waters. Ecology 81:904–920. [Google Scholar]

- Miner BG, Sultan SE, Morgan SG, Padilla DK, and Relyea RA. 2005. Ecological consequences of phenotypic plasticity. Trends Ecol Evol 20:685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moles AT, Ackerly DD, Webb CO, Tweddle JC, Dickie JB, and Westoby M. 2005. A brief history of seed size. Science 307:576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty EC, and Cannatella DC. 2004. Phylogenetic relationships of the North American chorus frogs (Pseudacris: Hylidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol 30:409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murren CJ, Maclean HJ, Diamond SE, Steiner UK, Heskel MA, Handelsman CA, Ghalambor CK, Auld JR, Callahan HS, Pfennig DW, Relyea RA, Schlichting CD, and Kingsolver J. 2014. Evolutionary change in continuous reaction norms. Am Nat 183:453–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murren CJ, Auld JR, Callahan H, Ghalambor CK, Handelsman CA, Heskel MA, Kingsolver JG, Maclean HJ, Masel J, Maughan H, Pfennig DW, Relyea RA, Seiter S, Snell-Rood E, Steiner UK, and Schlichting CD. 2015. Constraints on the evolution of phenotypic plasticity: costs of phenotype and costs of plasticity. Heredity 115:293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orizaola G and Braña F. 2004. Hatching responses of four newt species to predatory fish chemical cues. Ann Zool Fenn 41:635–645. [Google Scholar]

- Pennell MW, Eastman JM, Slater GJ, Brown JW, Uyeda JC, FitzJohn RG, Alfaro ME, and Harmon LJ. 2014. Geiger v2. 0: an expanded suite of methods for fitting macroevolutionary models to phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 30:2216–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci M 2001. Phenotypic integrations: Studying the ecology and evolution of complex phenotypes. Ecol Lett 6:256–272. [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci M, Pollard H, and Cruzan MB. 2003. Comparative studies of evolutionary responses to light environments in Arabidopsis. Am Nat 161:68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci M, Cammell K, and Schmitt J. 1999. Evolution of phenotypic plasticity a comparative approach in the phylogenetic neighbourhood of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Evol Biol 12:779–791. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard H, Cruzan M, and Pigliucci M. 2001. Comparative studies of reaction norms in Arabidopsis. I. Evolution of responses to daylength. Evol Ecol Res 3:129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Poo S, and Bickford DP. 2014. Hatching plasticity in a Southeast Asian tree frog. Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2014) 68:1733–1740. [Google Scholar]

- Price T, Lovette IJ, Bermingham E, Gibbs HL, and Richman AD. 2000. The imprint of history on communities of North American and Asian warblers. Am Nat 156:354–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyron RA, and Wiens JJ. 2013. Large-scale phylogenetic analyses reveal the causes of high tropical amphibian diversity. Proc Royal Soc London 280: 20131622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabosky DL, and Adams DC. 2012. Rates of morphological evolution are correlated with species richness in salamanders. Evolution 66:1807–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relyea RA 2007. Getting out alive: How predators affect the decision to metamorphose. Oecologia 152:389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revell LJ, Harmon LJ, and Collar DC. 2008. Phylogenetic signal, evolutionary process, and rate. Syst Biol 57:591–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JML 2001a. A comparative study of activity levels in larval anurans and response to the presence of different predators. Behav Ecol 12:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JML 2001b. The relative roles of adaptation and phylogeny in determination of larval traits in diversifying anuran lineages. Am Nat 157:282–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JML 2002a. Burst swim speed in tadpoles inhabiting ponds with different top predators. Evol Ecol Res 4:627–642. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JML 2002b. A comparative study of phenotypic traits related to resource utilization in anuran communities. Evol Ecol 16:101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Saenz D, Johnson JB, Adams CK, and Dayton GH. 2003. Accelerated hatching of southern leopard frog (Rana sphenocephala) eggs in response to the presence of a crayfish (Procambarus nigrocinctus) predator. Copeia 2003:646–649. [Google Scholar]

- Schalk G, Forbes MR, Weatherhead PJ. 2002. Developmental plasticity and growth rates of green frog (Rana clamitans) embryos and tadpoles in relation to a leech (Macrobdella decora) predator. Copeia 2002: 445–449. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting C, and Pigliucci M. 1998. Phenotypic evolution: a reaction norm perspective. Sinauer, Sunderland. [Google Scholar]

- Schluter D 2000. The Ecology of Adaptive Radiation. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeppner NM, and Relyea RA. 2008. Detecting small environmental differences: Risk-response curves for predator-induced behavior and morphology. Oecologia 154:743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev O, Rodríguez A, Hauswaldt S, Hugemann K, Vences M. 2015. Flatworns (Schmidtea nova) prey upon embryos of the common frog (Rana temporaria) and induce minor developmental acceleration. Amphibia-Reptilia 36:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, and Van Buskirk J. 1995. Phenotypic design, plasticity, and ecological performance in two tadpole species. Am Nat 145:211–233. [Google Scholar]

- Sota T, and Ishikawa R. 2004. Phylogeny and life-history evolution in Carabus (subtribe Carabina: Coleoptera, Carabidae) based on sequences of two nuclear genes. Biol J Linnean Soc 81:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens PR, and Wiens JJ. 2004. Convergence, divergence, and homogenization in the ecological structure of emydid turtle communities: The effects of phylogeny and dispersal. Am Nat 164:244–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler JS, and Karban R. 1997. A phylogenetic reconstruction of constitutive and induced resistance in Gossypium. Am Nat 149:1139–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchon JC, Gomez-Mestre I, and Warkentin KM. Hatching plasticity in tow temperate anurans: response to a pathogen and predation cues. Can J Zool 84:556–563. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buskirk J 2002. A comparative test of the adaptive plasticity hypothesis: Relationships between habitat and phenotype in anuran larvae. Am Nat 160:87–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonesh JR 2005. Egg predation and predator-induced hatching plasticity in the African reed frog, Hyperolius spinigularis. Oikos 110:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Warkentin KM 1995. Adaptive plasticity in hatching age: a response to predation risk trade-offs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:3507–3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb CO, Ackerly DD, McPeek MA, and Donoghue MJ. 2002. Phylogenies and community ecology. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 33:475–505. [Google Scholar]

- West-Eberhard MJ 2003. Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Wiens JJ, Graham CH, Moen DS, Smith SA, and Reeder TW. 2006. Evolutionary and ecological causes of the latitudinal diversity gradient in hylid frogs: treefrog trees unearth the roots of high tropical diversity. Am Nat 168:579–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens JJ, Sukumaran J, Pyron RA, and Brown RM. 2009. Evolutionary and biogeographic origins of high tropical diversity in Old World frogs (Ranidae). Evolution 63:1217–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winemiller KO 1991. Ecomorphological diversification in lowland freshwater fish assemblages from five biotic regions. Ecol Monogr 61:343–365. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.