Abstract

Background:

Menstrual cycle is an important indicator of women's reproductive health. However, menstruation has a different pattern within a few years after menarche, which might not be well understood by many adolescent girls.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 536 healthy menstruating females aged 10–19 years. Standardized self-reporting questionnaires were used to obtain relevant data. The categorical data were analyzed using Chi-square or Fisher's exact test.

Results:

Mean age of menarche was 13 ± 1.1 years with wide variations, i.e., 10–17 years. 73.1% had cycle duration of 21–35 days. More than half of them reported 5–6 days’ duration of menstrual blood flow and 12% of the participants had >7 days of flow. Long blood flow duration was more prevalent in early than in late adolescence. 30.1% reported abundant blood loss. 66.8% had dysmenorrhea and no difference was observed between early and late adolescents. Menstrual cycles tend to be shorter in early adolescence period.

Conclusion:

A comprehensive school education program on menarche and menstrual problems may help girls to cope better and seek proper medical assistance.

Keywords: Adolescence, females, menstruation

Introduction

Adolescence is the period of transition between puberty and adulthood. Menarche is one of the markers of puberty and therefore can be considered as an important event in the life of adolescent girls. Studies suggested that menarche tends to appear earlier in life as the sanitary, nutritional, and economic conditions of a society improve.[1,2] For most females, it occurs between the age of 10 and 16 years; however, it shows a remarkable range of variation.[3] The normal range for ovulatory cycles is between 21 and 35 days. While most periods last from 3 to 5 days, duration of menstrual flow normally ranges from 2 to 7 days. For the first few years after menarche, irregular and longer cycles are common.[1,2,3,4,5]

Menstrual disorders are a common presentation by late adolescence; 75% of girls experience some problems associated with menstruation including delayed, irregular, painful, and heavy menstrual bleeding, which are the leading reasons for the physician office visits by adolescents.[6] Menstrual patterns are also influenced by a number of host and environmental factors.[7] However, few studies in India have described the lifestyle factors associated with various menstrual cycle patterns. We therefore surveyed the current changes in the age of menarche in India adolescents. We also evaluated general menstruation patterns, the incidence of common menstrual disorders. Historically, the age at menarche has gradually decreased by about 4 months in every 10-year interval.[8] Some of these menstrual characteristics, such as irregularity in the menstrual cycle, premenstrual pain and discomfort, pain and discomfort at the time of menstrual discharge, and a heavy menstrual discharge, may affect the general and/or reproductive health of a woman.[9,10]

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out on 536 female students recruited from the educational institutions in the urban areas of a major city in South India. The selected women were explained about the protocol and the purpose of the study and were requested to complete the questionnaires to elicit information relating to demographic features, menarche age, and menstrual characteristics.

The demographic information included family details relating to family size, type, parent's education, occupation, house type, and possession of costly goods such as vehicles, computer, TV, DVD, refrigerator, and phones, and this information was used to derive their socioeconomic status (SES). The chronological age and age at menarche were also elicited.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee, University of Mysore.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were used to determine mean and percentages wherever applicable. The categorical data were analyzed using Chi-square or Fisher's exact test.

Results

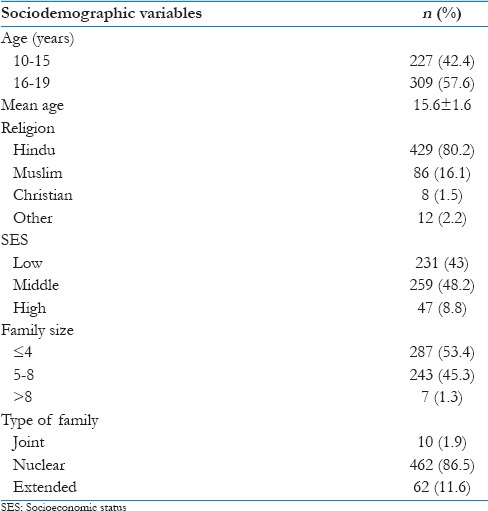

Subjective information is presented in Table 1; the participants’ age ranged from 10 to 19 years, with a mean of 15.6 ± 1.6 years.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the selected adolescents

Majority of the participants (80.2%) belonged to the families practicing Hinduism, and 86.5% of girls were from nuclear family. The girls belonged to low (43%), middle (48.2%), and high (8.8%) SES. Family size of the participants varied between <4 and >8 members; large families were less prevalent.

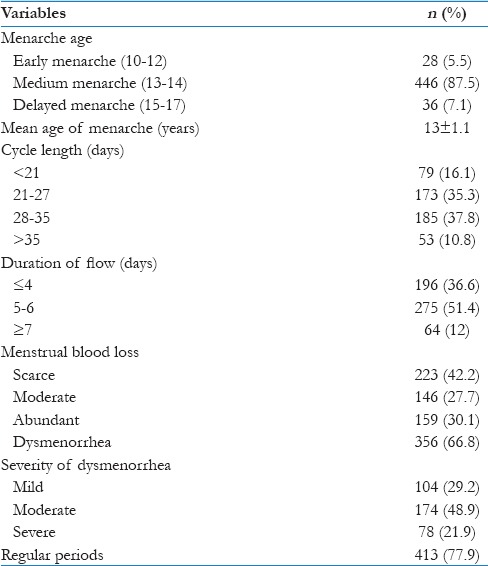

The menstrual pattern of the selected female students is presented in Table 2. It can be seen that mean age of menarche was 13 ± 1.1 years, exhibiting wide variations, i.e., 10–17 years among the participants. Cycle duration of 21–35 days was reported by 73.1% (n = 358); more than half of them reported 5–6 days’ duration of menstrual blood flow. Hence, 12% of the participants had >7 days of flow. Although this condition is found in a such a small part of the population, it is of concern as it is associated to higher blood loss, increasing the risk of anemia. Scarce-to-moderate blood loss during menstruation was reported by 69.9% (n = 369) of the population. abundant blood loss was experienced by 30.1% of the population. The overall prevalence of dysmenorrhea was 66.8%, and among them, 21.9% experienced severe pain. Regular cycles were reported by 77.9% of the participants; therefore, it is evident that irregularity of menstruation is frequent among adolescents.

Table 2.

Menstrual characteristics of young adolescent girls in Mysore, India

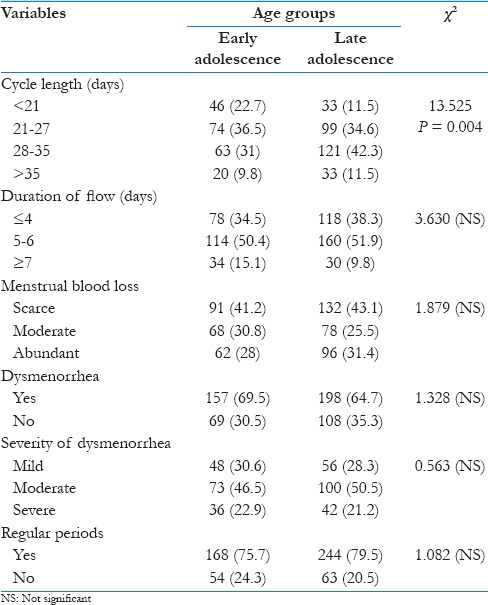

As Table 3 shows, short cycle length is more frequent among early adolescent participants. The prevalence of normal cycle length (28–35 days) is significantly higher in the late adolescence period.

Table 3.

Menstrual characteristics of adolescent girls according to their age

About 15.1% of the participants in the early adolescence period experienced long blood flow duration, while it was only 9.8% for the late adolescent participants. Statistically, we found a significant difference between duration of blood flow and adolescence period. It is evident from our results that 28%–31.4% of the participants in the two age categories, i.e., 10–15 and 16–19 years, respectively, experienced excessive bleeding (scores >80) as per the pictorial chart and 69.5%–67.4% were found to have dysmenorrhea. There was no significant difference among two groups according to the severity of menstrual pain. Menstrual irregularity however was of less frequent occurrence; 24.3% of participants in the early adolescent group (10–15 years of age) experienced frequent irregular menstruation than those in the late adolescence group.

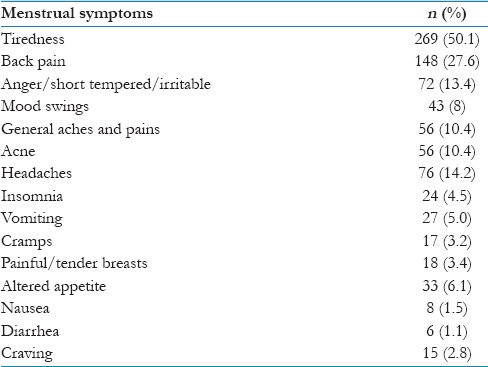

The frequently occurring symptoms of menstruation are presented in Table 4. The most common symptoms among girls during the menstrual periods were tiredness and back pain.

Table 4.

Frequency of the menstrual symptoms among adolescent subjects

Discussion

Adolescents comprise nearly one-fifth (22%) of the India's total population. The country also has the world's largest adolescent girl population (20%).[11]

Menstruation and menstrual health issues which is one of the major areas of concern in reproductive health affects a large number of women throughout their reproductive life from adolescence.

The present study was conducted to explore the menstrual characteristics among the unmarried adolescents across different age groups (early and late adolescence) and to find out association with menstrual pattern.

In the present study, the mean age of menarche was 13 ± 1.1 years, which is essentially similar to many other studies.[12,13]

Menarche age is the most widely used indicator of sexual maturation and influenced by many factors such as genetic and environmental conditions, family size, body mass index, SES, and level of education.[4,14]

Female anthropometry that reveals body composition has strong influence on their reproductive characteristics marked by the menarcheal age.[15]

An early menarcheal age is associated with increased risk for breast cancer, obesity, endometrial cancer, and uterine leiomyomata.[16,17,18,19] Furthermore, several studies have reported that age at menarche may relate to subsequent reproductive performance, such as age at first intercourse, age at first pregnancy, and risk of subsequent miscarriage.[20]

The prevalence of dysmenorrhea in our study was almost the same as other reports from India.[21,22]

Dysmenorrhea is the most common (66.8%) gynecological problem associated with adolescent females. Several other studies reported its prevalence range from 25% to 90% among women and adolescents girls.[23]

We found higher percentage of experiencing dysmenorrhea among participants in the early adolescence period (69.5% vs. 64.7%); however, statistically difference was not significant.

Majority of the participants experienced dysmenorrhea during menstruation although more than three-fourth of them had mild-to-moderate pain. However, about 30% of them complained of severe pain. Comparing with other reports from India in higher age group (adults), our results showed higher frequency of severe menstrual pain and it may be due to effect of age on severity of pain.[13]

This is controversial as several studies noted that older women are more likely to report decreasing severity of primary dysmenorrhea.[24,25] However, another study found that the severity of dysmenorrhea was not associated with age as an isolated factor.[26]

Abundant menstrual blood loss was also a common problem among the adolescents in this study. The most common cause of heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents is dysfunctional uterine bleeding related to anovulation;[27] therefore, it is expected to be higher in the adolescence period.

The present study showed that the menstrual cycle and the duration of menstrual blood loss tend to become regular and shorter, respectively, with the increase in age, suggesting a gradual accomplishment of ovarian maturity during the time.

When we surveyed general menstruation patterns, we found that frequency of irregular menstruation was higher in early adolescence, but contrary to our expectations, no significant association was found between age and frequency of irregular menstrual cycles.

Menstrual symptoms are a broad collection of affective and somatic concerns that occur around the time of menses. Some women manage their monthly periods easily with few or no concerns, while others experience a number of physical and emotional symptoms that may cause psychological and physical discomfort.[28]

The most common symptom present in the adolescent girls during the menstrual periods was tiredness (50.1%), and the second most prevalent symptom was back pain (27.6%). Our observations were similar to that reported by Agarwal and Agarwal.[29]

In the present study, occurrence rate of certain discomforts among adolescents indicates the extent of sufferings; the adolescence females undergo with each cycle of menstruation. The information suggests that treatment approaches should be developed as the target group is vulnerable (the target group was adolescents who are more vulnerable than adults).

Conclusion

Dysmenorrhea and menstrual irregularity are more prevalent among adolescent females. Common menstrual symptoms are tiredness, backache, and headache. It appears that occurrence of dysmenorrhea is increasing in the population; such sufferings would affect the productivity among females. Therefore, it can be stated that a comprehensive school education program on menarche and menstrual problems may help girls to cope better and seek proper medical assistance.

Limitations of the study

The study is conducted in the selected region; therefore, generalizing must be done with care. The findings may not be representative the menstrual characteristics in whole South India. Moreover, the study and the results are related to an urban area, so it might not be a good representative for rural areas.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to all participants.

References

- 1.Kaplowitz P. Pubertal development in girls: Secular trends. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18:487–91. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000242949.02373.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abioye-Kuteyi EA, Ojofeitimi EO, Aina OI, Kio F, Aluko Y, Mosuro O, et al. The influence of socioeconomic and nutritional status on menarche in Nigerian school girls. Nutr Health. 1997;11:185–95. doi: 10.1177/026010609701100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz A, Laufer MR, Breech LL American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Menstruation in girls and adolescents: Using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2245–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas F, Renaud F, Benefice E, de Meeüs T, Guegan JF. International variability of ages at menarche and menopause: Patterns and main determinants. Hum Biol. 2001;73:271–90. doi: 10.1353/hub.2001.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams Hillard PJ. Menstruation in young girls: A clinical perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:655–62. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)01660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee LK, Chen PC, Lee KK, Kaur J. Menstruation among adolescent girls in Malaysia: A cross-sectional school survey. Singapore Med J. 2006;47:869–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowland AS, Baird DD, Long S, Wegienka G, Harlow SD, Alavanja M, et al. Influence of medical conditions and lifestyle factors on the menstrual cycle. Epidemiology. 2002;13:668–74. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200211000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JC, Yu BK, Byeon JH, Lee KH, Min JH, Park SH, et al. A study on the menstruation of Korean adolescent girls in Seoul. Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54:201–6. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2011.54.5.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox SI. Human Physiology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodenough J, WR Betty A, McGuire B. Human Biology: Personal, Environmental and Social Concerns. New York: Saunders College Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Census of India. Provisional Population Totals: India, Registrar General of India. MOH, GOI. 2001. [Last accessed on 2015 May 15]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/WHO_Country_Cooperation_Strategy_-_India_Health_Development_Challenges.pdf .

- 12.Cakir M, Mungan I, Karakas T, Girisken I, Okten A. Menstrual pattern and common menstrual disorders among university students in Turkey. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:938–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A, Kiran D, Singh H, Nel B, Singh P, Tiwari P, et al. Prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhea: A problem related to menstruation, among first and second year female medical students. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;52:389–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chumlea WC, Schubert CM, Roche AF, Kulin HE, Lee PA, Himes JH, et al. Age at menarche and racial comparisons in US girls. Pediatrics. 2003;111:110–3. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lassek WD, Gaulin SJ. Brief communication: Menarche is related to fat distribution. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;133:1147–51. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braithwaite D, Moore DH, Lustig RH, Epel ES, Ong KK, Rehkopf DH, et al. Socioeconomic status in relation to early menarche among black and white girls. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:713–20. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9284-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Lenthe FJ, Kemper CG, van Mechelen W. Rapid maturation in adolescence results in greater obesity in adulthood: The Amsterdam growth and health study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:18–24. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McPherson CP, Sellers TA, Potter JD, Bostick RM, Folsom AR. Reproductive factors and risk of endometrial cancer. The Iowa women's health study. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:1195–202. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Goldman MB, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Barbieri RL, et al. A prospective study of reproductive factors and oral contraceptive use in relation to the risk of uterine leiomyomata. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:432–9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schor N. Abortion and adolescence: Relation between the menarche and sexual activity. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 1993;6:225–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumbhar SK, Sujana M, Reddy B, Reddy KR, Divya Bhargavi K, Balkrishna C. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea among adolescent girls (14-19 yrs) of Kadapa district and its impact on quality of life: A cross sectional study. Natl J Community Med. 2011;2:265–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avasarala AK, Panchangam S. Dysmenorrhoea in different settings: Are the rural and urban adolescent girls perceiving and managing the dysmenorrhoea problem differently? Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:246–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.43231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daley AJ. Exercise and primary dysmenorrhoea: A comprehensive and critical review of the literature. Sports Med. 2008;38:659–70. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pullon S, Reinken J, Sparrow M. Prevalence of dysmenorrhoea in Wellington women. N Z Med J. 1988;101:52–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weissman AM, Hartz AJ, Hansen MD, Johnson SR. The natural history of primary dysmenorrhoea: A longitudinal study. BJOG. 2004;111:345–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundell G, Milsom I, Andersch B. Factors influencing the prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhoea in young women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:588–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McEvoy M, Chang J, Coupey SM. Common menstrual disorders in adolescence: Nursing interventions. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2004;29:41–9. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200401000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Negriff S, Dorn LD, Hillman JB, Huang B. The measurement of menstrual symptoms: Factor structure of the menstrual symptom questionnaire in adolescent girls. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:899–908. doi: 10.1177/1359105309340995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal AK, Agarwal A. A study of dysmenorrhea during menstruation in adolescent girls. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:159–64. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]