Editor’s Note

New knowledge about microglia is so fresh that it’s not even in the textbooks yet. Microglia are cells that help guide brain development and serve as its immune system helpers by gobbling up diseased or damaged cells and discarding cellular debris. Our authors believe that microglia might hold the key to understanding not just normal brain development, but also what causes Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, autism, schizophrenia, and other intractable brain disorders.

Early in the 19th century, the nervous system was believed to be a continuous network— essentially one giant cell with many spidery extensions bundled to form the brain and spinal cord. The discovery that nervous tissue, like any other bodily tissue, is composed of individual cells upended this theory, but the idea of interconnectedness persists.

Indeed, one of the most surprising findings in the neuroscience field in recent years is the degree of the nervous system’s interconnection. We’ve learned that its cells are intertwined not only with each other but also with those of the immune system, and that the same immune cells that work in the body to repair damaged tissues and defend us from infections are also critical for normal brain development and function.1,2 Some of these immune cells, called microglia, live permanently interspersed with neurons in the central nervous system and play crucial roles in nerve cell development, brain surveillance, and circuit sculpting.

In an article about microglia in Biomedicine in 2016, the author wrote that “scientists for years have ignored microglia and other glia cells in favor of neurons. Neurons that fire together allow us to think, breathe, and move. We see, hear, and feel using neurons, and we form memory and associations when the connections between different neurons strengthen at the junctions between them, known as synapses. Many neuroscientists argue that neurons create our very consciousness.” However, what we know now is that neurons don’t function very well, or at all, without their glial cell neighbors.

There is, in fact, perhaps no more dramatic a shift in focus in recent neuroscience than the ascent of these “other brain cells”—so dramatic in fact, that the knowledge has yet to seep into neuroscience textbooks and has only just begun to permeate the field. This knowledge, some of it described here, likely represents only the tip of the iceberg.

The Collective World of Glia

Microglia are the permanent resident immune cells of the brain and spinal cord, sharing many similarities with macrophages—the cells that destroy pathogens—outside the central nervous system. First impressions were underwhelming. In the 1800s, the pathologist Rudolf Virchow noted the presence of small round cells packing the spaces between neurons and named them “nervenkitt” or neuroglia,” which can be translated to putty or glue. One variety of these cells, known as astrocytes, was defined in 1893.

Microglia themselves were first identified and characterized by Spanish neuroanatomists Nicolas Achucarro and Pio del Río-Hortega, both students of Santiago Ramon y Cajal, the undisputed “father of neuroscience,” early in the 20th century.4, 5 Urban legend has it that del Rio-Hortega suggested that microglia looked like aliens from another realm—which is, metaphorically, not far off, given their origin in the fetal yolk sac6 rather than the neural ectoderm from which all other brain cells develop. The relatively late entry of microglia into the neuroscience field a century ago may be in part responsible for the limited attention and understanding they have received. But since their origin was fully described seven years ago, the importance of microglia has gradually been recognized.

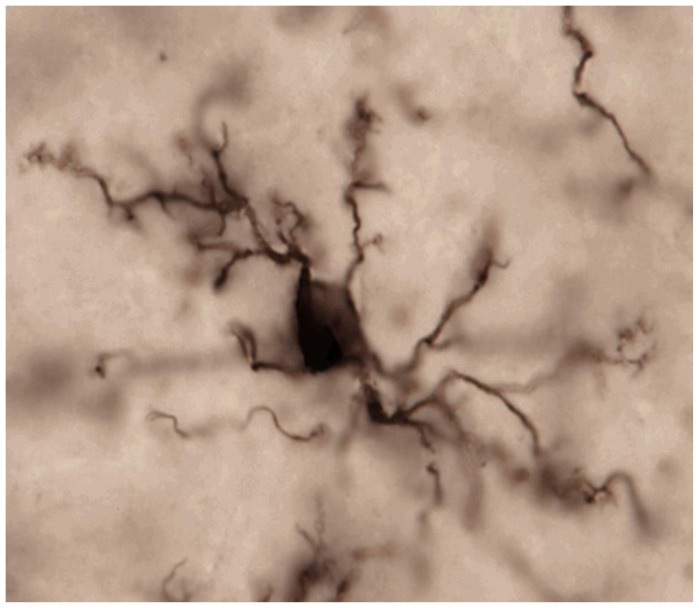

Microglia are distributed more or less uniformly throughout the adult brain, in both white and grey matter, but in varying densities, with the highest concentrations appearing in parts of the brain stem (the substantia nigra), parts of the reward circuit of the brain (the basal ganglia), and the hippocampus.7 Each cell has a small cell body and numerous arms that extend throughout the surrounding tissue (Figure 1), maintaining distinct boundaries and rarely overlapping with the arms of a neighboring microglial cell.8 Like police officers, these cells constantly survey their environment for trouble and are often the first responders to injury or disease. On their surface are a tremendous diversity of receptors for various threats, including bacterial, viral, and fungal pathogens, toxins, and xenobiotics, as well as noxious compounds released from dead or dying cells during traumatic brain injury, ischemia, and neurodegeneration.9–12 Microglia from different brain regions are also somewhat heterogeneous, possessing a different collection of cell surface markers (sort of like little flags on the membrane that distinguish one cell from another), though the functional consequences of these differences are not yet fully understood.13

Figure 1.

Microglia in the mature, healthy brain exhibit small cell bodies and multiple long, thin processes (arms) that they use to constantly scan and survey their local environments within brain tissue. Photo credit S. Bilbo.

Upon detection of trouble, microglia mount specialized responses, destroying pathogens and calling for help from other cells via signaling molecules called cytokines. They organize the responses of surrounding cells to alter neuron function, recruit additional immune cells, aid in tissue repair, or induce cell death.8 Their constant communication with neighboring neurons and microglia ensure that each microglial cell is adequately placed and functioning at the right level of activity.14

Microglia Never Rest

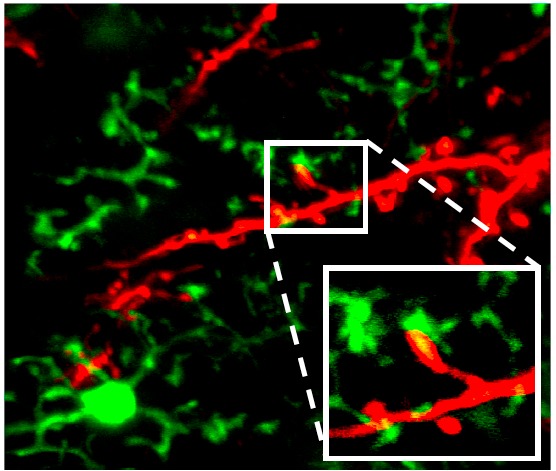

It was traditionally assumed that microglia remained in a resting or quiescent state until mobilized by a threat, a transformation termed activation;15 the cells retract their arms and adopt an amoeboid shape in which they can move spontaneously and actively.16 In recent years, however, the notion of “resting” microglia was upended by a series of elegant experiments.17–19 Using a green florescent protein (GFP) to color microglia and fancy two-photon microscopy to image them, researchers could watch these cells survey the brain through the thinned skulls of mice. Time-lapse videography revealed that while the bodies of cortical microglia remain relatively stationary, their arms are highly and spontaneously active, collectively surveying the entire brain every few hours.19 These studies indicated for the first time that microglia are not simply “reactive” immune cells that mobilize following infection or injury, but active sentinels (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Microglia dynamically interact with synaptic elements in the healthy brain. Two-photon imaging in the olfactory bulb of adult mice shows processes of CX3CR1-GFP-positive microglia connecting to tdTomato-labeled neurons. Reprinted with permission from Jenelle Wallace at Harvard University (Hong and Stevens, 201620).

But why must microglia be so active if they are merely watching for threats? Several groups have argued that they play an essential role in monitoring synaptic activity as well.14, 21–24 Synapses, the connections between neurons, are in effect the telephone wires of the brain, allowing these cells to electrically communicate with one another using their axons as transmitters and dendrites as the receivers. Microglial arms make direct contact with axons and dendrites,25, 26 implying that microglia may be carefully listening in on nerve cell conversations. To see if this is true, scientists devised experiments to test whether microglia reacted to what they “overheard.” Indeed, when neuronal activity in the visual cortex was reduced (by maintaining the young mice in darkness), the microglia paid less attention to (made fewer contacts with) those neurons that normally would have received input about light signals, presumably because those neurons were talking less.25,26 In contrast, increasing neuronal activity (by repetitive visual stimulation) resulted in increased contact by the microglial arms, which preferentially contacted and wrapped around neurons with high activity and energy use. Contact by microglial processes was associated with a subsequent decrease in spontaneous neuron firing, which may be a homeostatic response.

Due to their ability to listen to synapses and their role as macrophages (which are good at engulfing and eating things), many scientists wondered whether microglia might also play a role in synaptic pruning.

Developmental Synaptic Pruning

As the brain develops in the womb and during childhood and puberty, it needs to be gradually and carefully re-wired, with unneeded synapses removed or re-routed to more appropriate targets. This synaptic pruning is carried out, in part, by microglia.22,27 Indeed, electron microscopy and high-resolution assays have found the remnants of synapses digesting within microglia in the mouse visual system, hippocampus, and other brain regions during the critical periods of synaptic pruning, the first few weeks of life in mice. In the visual system, as with all sensory systems, this pruning is dependent on neuron activity and sensory experience,22,25 with microglia preferentially eliminating less-active synapses. But how do they know exactly which synapses to eat?

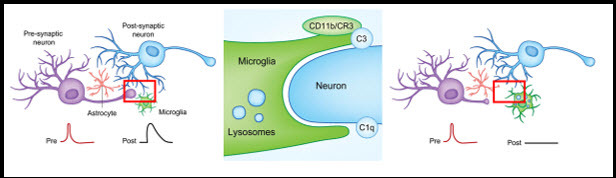

The nervous and immune systems share an array of molecules that have both specialized and analogous functions. Surprisingly, several proteins associated with innate (generalized) and adaptive (highly specialized) immunity are found in synapses, where they regulate circuit development and plasticity.28–30 Among these substances are components of the classical complement cascade, which coat troublesome cells such as bacteria with “eat me” signals that attract macrophages that then engulf and digest them. A key molecule in this process is called C3. In the healthy developing mouse brain, C3 is widely produced and localizes to subsets of immature synapses.31 There, it attracts microglia, the only nervous system cell type that has a C3 receptor, which then engulf the synapse, much as macrophages destroy bacteria outside the brain (Figure 3).22 Mice without C3 and other proteins in this pathway have too many synapses and develop sustained defects in neuronal connectivity and brain wiring. Such excessive connectivity could result in increased excitability and seizures, as was demonstrated in mice that lack another protein in the complement pathway, C1q.32

Figure 3.

Synaptically coupled (i.e. communicating) neurons are under constant surveillance by glial cells, including microglia. If a neuronal synapse becomes “tagged” with complement protein C3, microglia recognize the tag with their C3 receptor (CR3/CD11b). This signal tells the microglia to engulf, or phagocytosis, and degrade the synapse. After microglial synaptic pruning, the eliminated synapse changes the way neurons communicate. Adapted from Lacagnina et al., 20173.

There are likely other immune-related molecules (one is a sort of small, signaling cytokine or “chemokine” called Fractalkine33) that work in concert with the complement cascade to ensure that the right synapses are pruned at the right time. It is possible that different mechanisms regulate pruning in different contexts, e.g. across brain regions and stages of development. Aberrant pruning during developmental critical periods could contribute to neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism and schizophrenia, as discussed below. Indeed, emerging genetics identifies variants in complement protein C4 that increase the amount of complement in the brain and the risk of developing schizophrenia,34 suggesting a model in which too-much-of-a-good-thing results in defective brain wiring.

Implications for Disease

As suggested above, synaptic pruning is a sensitive process; destroying too many or too few synapses will be detrimental. Factors in the environment, such as infectious disease, and within a person’s own genome, such as mutation, may affect microglia’s ability to find and destroy the appropriate synapses, leading, perhaps, to psychiatric conditions such as autism or schizophrenia, or neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. Since they have complex and diverse functions in the brain, there are likely many ways in which microglia might contribute to disease risk and pathogenesis. Understanding when and where they become dysfunctional in these disorders will be critical to understanding how they influence relevant circuits and brain regions. Targeting the mechanisms that are dysregulated has the potential to arrest or reverse neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders where these cells play a role.

Early-Life Immune Activation

Microglia are immune cells, and thus respond to infection and inflammation. This may interfere with their normal duties (for instance, synaptic pruning), particularly if those infections happen during a critical time in brain development. Microglia develop slowly over normal embryonic and postnatal development; they start out as round, macrophage-like cells and gradually transform into the mature cell type illustrated in Figure 1. The functional implications of this shift in cell shape and structure are not fully understood, but many disorders are associated with strange-looking microglia. For instance, amoeboid (round) microglia are found in the post-mortem brains of autistic patients, even in later life, at a time when the cells should have long, thin processes, suggesting dysfunction in these cells.35–37

Studies with rats have shown that bacterial infection in newborn rats strongly activates the immune system, and that in young adulthood their microglia look round and dysfunctional, like those in the brains of patients with autism.38,39 These newborn-infected rats also exhibit social deficits40 and profound problems with learning and memory in adulthood—but only if they receive an injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a key component in bacterial cells, around the time of learning.39, 41 This “second hit” apparently reactivates the immune system, which kicks the microglia into overdrive, overproducing a cytokine called IL-1β. This compound is vital for normal synaptic function and the formation of memories, but too much impairs memory.39 So, the microglia of rats activated by infection as newborns act a bit like unruly teenagers weeks later, overreacting to the slightest provocation and causing problems.

Because microglia are long-lived cells (with slow turnover, about 28 percent per year in humans42) and can remain functionally activated, these insults early in life may persist into the future. Many additional studies with rodents have demonstrated that diverse inflammatory factors beyond infection, including stressors or environmental toxins, may similarly cause persistent changes in microglia that impact adult behavior.43 Could such early-life insults—and their effects on microglia—result in serious problems much later in life?

Microglia in Neurodegenerative Disorders

Activated microglia and neuroinflammation are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and frontal temporal dementia.44 These hallmarks were long considered to be symptoms rather than causes of disease, but new genetic studies indicate that they are indeed important, as many genes that increase risk of developing AD are enriched or specifically expressed in microglia.45

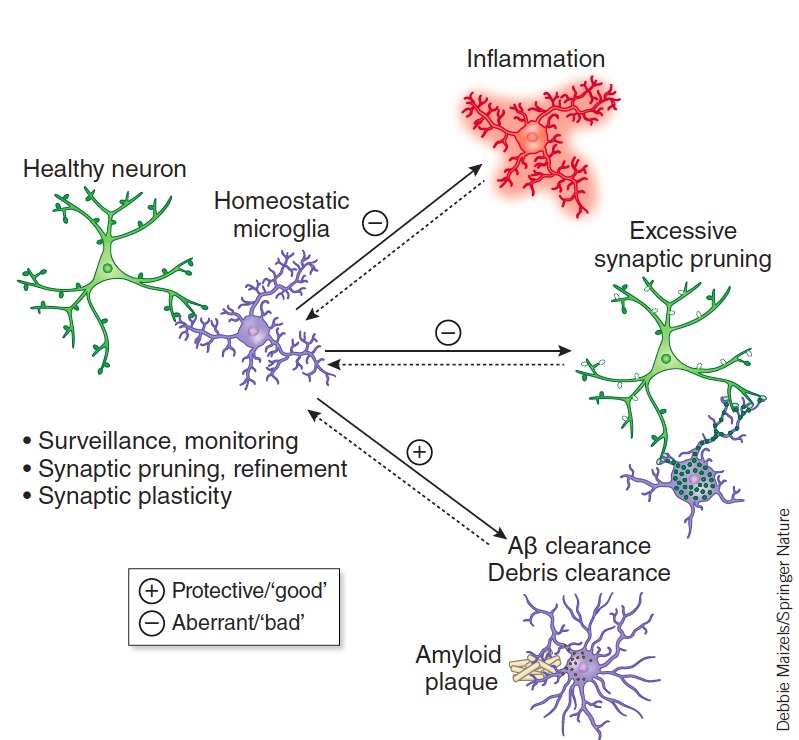

Microglia have complex roles that can both attenuate and exacerbate AD’s pathogenesis. When the AD brain is cluttered with toxic amyloid plaques, microglia surround them, engulfing or degrading them and secreting inflammatory cytokines in the process (Figure 4).46 Failure to clean up the dying cells, cellular debris, and toxic proteins like the amyloid plaques would contribute to inflammation and neurodegeneration. But overproduction of cytokines by microglia is also harmful. And excessive engulfment of synapses by microglia might contribute to cognitive impairment in AD.20,47,48

Figure 4. Microglia States in Health and Disease.

Microglia have complex roles that are both beneficial and detrimental to disease pathogenesis including engulfing or degrading toxic proteins (i.e., amyloid plaques) and promoting neurotoxicity through excessive inflammatory cytokine release. Aberrations in microglia’s normal homeostatic functions (Surveillance, synaptic pruning and plasticity) may also contribute to excessive synapse loss and cognitive dysfunction in AD and other diseases. Salter and Stevens 2016 46 with permission.

Synapse loss is in fact a hallmark of AD and many other neurodegenerative diseases, and can occur years before clinical symptoms—and fewer synapses in the AD’s brain correlate with cognitive decline.49,50 The mechanisms underlying synapse loss and dysfunction are poorly understood, although there are clues. Classical complement cascade proteins—the “eat me” signal involved in developmental pruning—are abundant in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease in the hippocampus and vulnerable brain regions, binding to synapses before overt plaque deposition and signaling microglia to destroy those synapses. Similarly, recent evidence suggests that complement activation and microglia-mediated synaptic pruning contribute to neurodegeneration in mouse models of frontal temporal dementia,51 glaucoma, and other diseases.31,52

These findings imply that the same pathway that prunes excess synapses in development is inappropriately activated in AD and may be a common mechanism underlying other neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, understanding the signals that trigger microglia to prune vulnerable circuits could provide important insights into these diseases and novel therapeutic targets. Given the diverse and complex activity of microglia in the healthy and diseased brain, there is a critical need for new biomarkers that relate specific microglial functional states to disease progression and pathobiology. Newly developed approaches to single-cell RNA sequencing and profiling of rodent and human microglia are likely to be fruitful here.

The Way Forward

We are just beginning to understand how microglia work in health and disease. But what we already know of their diverse roles in the healthy nervous system strongly suggests that some neurodevelopmental53 and neurodegenerative disorders result in part from their dysfunction. Targeting these aberrant functions, thereby restoring homeostasis, may thus yield novel paradigms for therapies that were inconceivable within a neuron-centric view of the brain. But recent findings about the varying roles of microglia have come primarily from research with mice and rats, and it will be critical to understand which translate to humans. An investment in developing new models of disease, including human cell models,46 is an essential next step toward clarifying whether the microglia-targeted therapeutic approaches emerging from rodent studies can, in fact, be used to treat human diseases.

Footnotes

Beth Stevens, Ph.D., is an associate professor at Harvard Medical School in the FM Kirby Neurobiology Center at Boston Children’s Hospital and an institute member of the Broad Institute and Stanley Center for Neuropsychiatric Research. Her most recent work seeks to uncover the role that microglial cells play in neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. She and her team recently identified how microglia affect synaptic pruning, the critical developmental process of cutting back on synapses that occurs between early childhood and puberty. Stevens was named a MacArthur Fellow by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation in 2015, received the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers, and the Dana Foundation Award and Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar in Aging Award. Stevens received her B.S. at Northeastern University, carried out her graduate research at the National Institutes of Health, and received her Ph.D. from University of Maryland. She completed her postdoctoral research at Stanford University with Ben Barres.

Staci Bilbo, Ph.D., is an associate professor of pediatrics and neuroscience at Harvard Medical School and the director of research for the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital for Children. Her research is broadly focused on the mechanisms by which the immune and endocrine systems interact with the brain to impact health and behavior. Bilbo was the recipient of the Robert Ader New Investigator Award from the Psychoneuroimmunology Research Society (PNIRS) in 2010 and the Frank Beach Young Investigator Award from the Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology (SBN) in 2011. Bilbo has served on the board of directors for the PNIRS, and was the Invited Mini-Review Editor for Brain, Behavior and Immunity from 2012–15. She has served on the editorial board since 2010. Bilbo received her B.A. in psychology and biology from the University of Texas at Austin and her Ph.D. in neuroendocrinology at Johns Hopkins University. She was on the faculty at Duke University from 2007–2016 before she joined the faculty at Harvard in 2017.

References

- 1.Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33(3):267–286. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deverman BE, Patterson PH. Cytokines and CNS development. Neuron. 2009;64(1):61–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacagnina MJ, Rivera PD, Bilbo SD. Glial and Neuroimmune Mechanisms as Critical Modulators of Drug Use and Abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):156–177. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sierra A, de Castro F, Del Rio-Hortega J, Rafael Iglesias-Rozas J, Garrosa M, Kettenmann H. The “Big-Bang” for modern glial biology: Translation and comments on Pio del Rio-Hortega 1919 series of papers on microglia. Glia. 2016;64(11):1801–1840. doi: 10.1002/glia.23046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tremblay ME, Lecours C, Samson L, Sanchez-Zafra V, Sierra A. From the Cajal alumni Achucarro and Rio-Hortega to the rediscovery of never-resting microglia. Front Neuroanat. 2015;9:45. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, … Merad M. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330(6005):841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Dri P, Gordon S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1990;39(1):151–170. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kierdorf K, Prinz M. Factors regulating microglia activation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:44. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanisch UK. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia. 2002;40(2):140–155. doi: 10.1002/glia.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucin KM, Wyss-Coray T. Immune activation in brain aging and neurodegeneration: too much or too little? Neuron. 2009;64(1):110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annual Review of Immunology. 2009;27:119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528. (Journal Article) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saijo K, Glass CK. Microglial cell origin and phenotypes in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(11):775–787. doi: 10.1038/nri3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Agostino PM, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Anandasabapathy N, Bulloch K. Brain dendritic cells: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124(5):599–614. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1018-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kettenmann H, Hanisch UK, Noda M, Verkhratsky A. Physiology of microglia. Physiological Reviews. 2011;91(2):461–553. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends in neurosciences. 1996;19(8):312–318. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stence N, Waite M, Dailey ME. Dynamics of microglial activation: a confocal time-lapse analysis in hippocampal slices. Glia. 2001;33(3):256–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV, Zuo Y, Jung S, … Gan WB. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(6):752–758. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, Sunshine MJ, Kreutzberg GW, Sher A, Littman DR. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(11):4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science. 2005;308(5726):1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, Frouin A, Li S, Ramakrishnan S, … Stevens B. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science. 2016;352(6286):712–716. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graeber MB. Changing face of microglia. Science (New York, NY) 2010;330(6005):783–788. doi: 10.1126/science.1190929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, Yamasaki R, … Stevens B. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74(4):691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Stevens B. The “quad-partite” synapse: microglia-synapse interactions in the developing and mature CNS. Glia. 2013;61(1):24–36. doi: 10.1002/glia.22389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tremblay ME, Majewska AK. A role for microglia in synaptic plasticity? Communicative & integrative biology. 2011;4(2):220–222. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.2.14506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tremblay ME, Lowery RL, Majewska AK. Microglial interactions with synapses are modulated by visual experience. PLoS biology. 2010;8(11):e1000527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wake H, Moorhouse AJ, Jinno S, Kohsaka S, Nabekura J. Resting microglia directly monitor the functional state of synapses in vivo and determine the fate of ischemic terminals. J Neurosci. 2009;29(13):3974–3980. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4363-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schafer DP, Stevens B. Phagocytic glial cells: sculpting synaptic circuits in the developing nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23(6):1034–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boulanger LM. Immune Proteins in Brain Development and Synaptic Plasticity. Neuron. 2009;64(1):93–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shatz CJ. MHC class I: an unexpected role in neuronal plasticity. Neuron. 2009;64(1):40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephan AH, Barres BA, Stevens B. The complement system: an unexpected role in synaptic pruning during development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:369–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE, Howell GR, Christopherson KS, Nouri N, … Barres BA. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell. 2007;131(6):1164–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu Y, Jin X, Parada I, Pesic A, Stevens B, Barres B, Prince DA. Enhanced synaptic connectivity and epilepsy in C1q knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(17):7975–7980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913449107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paolicelli RC, Bolasco G, Pagani F, Maggi L, Scianni M, Panzanelli P, … Gross CT. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science. 2011;333(6048):1456–1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sekar A, Bialas AR, de Rivera H, Davis A, Hammond TR, Kamitaki N, … McCarroll SA. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature. 2016;530(7589):177–183. doi: 10.1038/nature16549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan JT, Chana G, Pardo CA, Achim C, Semendeferi K, Buckwalter J, … Everall IP. Microglial activation and increased microglial density observed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(4):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardo CA, Vargas DL, Zimmerman AW. Immunity, neuroglia and neuroinflammation in autism. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17(6):485–495. doi: 10.1080/02646830500381930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, Pardo CA. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Ann Neurol. 2005;57(1):67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bland ST, Beckley JT, Young S, Tsang V, Watkins LR, Maier SF, Bilbo SD. Enduring consequences of early-life infection on glial and neural cell genesis within cognitive regions of the brain. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(3):329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williamson LL, Sholar PW, Mistry RS, Smith SH, Bilbo SD. Microglia and memory: modulation by early-life infection. J Neurosci. 2011;31(43):15511–15521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3688-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bilbo SD, Yirmiya R, Amat J, Paul ED, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Bacterial infection early in life protects against stressor-induced depressive-like symptoms in adult rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bilbo SD, Biedenkapp JC, Der-Avakian A, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF. Neonatal infection-induced memory impairment after lipopolysaccharide in adulthood is prevented via caspase-1 inhibition. J Neurosci. 2005;25(35):8000–8009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1748-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reu P, Khosravi A, Bernard S, Mold JE, Salehpour M, Alkass K, … Frisen J. The Lifespan and Turnover of Microglia in the Human Brain. Cell Rep. 2017;20(4):779–784. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bilbo SD, Block CL, Bolton JL, Hanamsagar R, Tran PK. Beyond infection - Maternal immune activation by environmental factors, microglial development, and relevance for autism spectrum disorders. Exp Neurol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ransohoff RM. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science. 2016;353(6301):777–783. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Efthymiou AG, Goate AM. Late onset Alzheimer’s disease genetics implicates microglial pathways in disease risk. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salter MW, Stevens B. Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nat Med. 2017;23(9):1018–1027. doi: 10.1038/nm.4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hong S, Stevens B. Microglia: Phagocytosing to Clear, Sculpt, and Eliminate. Dev Cell. 2016;38(2):126–128. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi Q, Chowdhury S, Ma R, Le KX, Hong S, Caldarone BJ, … Lemere CA. Complement C3 deficiency protects against neurodegeneration in aged plaque-rich APP/PS1 mice. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(392) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeKosky ST, Scheff SW, Styren SD. Structural correlates of cognition in dementia: quantification and assessment of synapse change. Neurodegeneration. 1996;5(4):417–421. doi: 10.1006/neur.1996.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, … Katzman R. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(4):572–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lui H, Zhang J, Makinson SR, Cahill MK, Kelley KW, Huang HY, … Huang EJ. Progranulin Deficiency Promotes Circuit-Specific Synaptic Pruning by Microglia via Complement Activation. Cell. 2016;165(4):921–935. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howell GR, Macalinao DG, Sousa GL, Walden M, Soto I, Kneeland SC, … John SW. Molecular clustering identifies complement and endothelin induction as early events in a mouse model of glaucoma. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1429–1444. doi: 10.1172/JCI44646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hanamsagar R, Bilbo SD. Environment matters: microglia function and dysfunction in a changing world. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2017;47:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]