Abstract

Peripheral veins often contain tortuosities and valves that hinder the effective passage of intravenous catheters to the full extent of catheter length. This report describes a methodology termed flick-spin that has proven efficacious for venous catheter passage in tortuous and valve-rich peripheral veins. The method relies on (1) applying longitudinal tension to the vessel in an attempt to straighten it, (2) rotating or spinning the catheter along its longitudinal axis, and (3) flicking the skin or visible vein just beyond the catheter tip, all during catheter advancement. Additionally, lateral pressure may also be applied to the vessel—ie, proximal to the catheter tip and during catheter advancement—to fine-tune catheter tip direction. The report contains multiple illustrations to communicate the anatomic, physiologic, and technical underpinnings of the technique, as well as instructions for troubleshooting common problems.

Peripheral veins often contain tortuosities and valves that hinder the effective passage of intravenous catheters to the full extent of catheter length. Although these tortuosities and valves can often be avoided through a process of vein selection—ie, valves can oftentimes be spotted as causing irregularities (eg, lumps, indentations) in the vessel’s external appearance—they also can be first discovered mid-cannulation when a catheter fails to advance or the vessel begins to displace from its normal course (beginning in close proximity to the distal tip of the catheter) during catheter advancement. Attempting to further forcefully advance the catheter—especially in more friable or thin-walled vessels, as can occur in sedentary patients or those receiving immunosuppressive drugs (including corticosteroids) or cancer chemotherapy—may result in vessel fracture and local hematoma formation.

Herein, I describe a methodology termed flick-spin that has proven efficacious for venous catheter passage in tortuous and valve-rich peripheral veins. The method relies on (1) applying longitudinal tension to the vessel in an attempt to straighten it, (2) rotating or spinning the catheter along its longitudinal axis, and (3) flicking the skin or visible vein just beyond the catheter tip, all during catheter advancement. Additionally, lateral pressure may also be applied to the vessel—ie, proximal to the catheter tip and during catheter advancement—to fine-tune catheter tip direction.

In understanding this methodology, it is of value to review the relationship among the anatomy of venous valves, the orientation and caliber of the vessel lumen, and free passage of a catheter within a vessel lumen and through a venous valve. In all descriptions, locations will be described in relationship to the body’s core, the direction of blood flow, or the orientation of the flexible catheter and its obturator.

Venous valves are typically described as bicuspid,1, 2, 3 and they oftentimes have a small sinus on the downstream side of the valve, creating apparent lumps in the vessel’s external anatomy. Catheter passage through a valve should occur more freely if the orientation of the vessel, catheter, and valve os (assumed to be at the center of the valve) share a common axis. As such, longer portions of straight veins, and more extensive passage of the catheter within the vein before the catheter enters the valve os, should direct the catheter tip toward the center of the vein and valve (Figure 1, A). This should be true whether the situation involves a relatively small-bore catheter in a large-bore vein (in which contact between the catheter and vessel wall are minimal) or a relatively large-bore catheter in a smaller vein (in which contact between the catheter and vessel wall are considerable). In contrast, tortuosities just proximal to the valve may tend to direct the catheter tip toward the junction of the vein wall and valve leaflet attachment, ie, an ideal setup for obstruction to catheter advancement (Figure 1, B). Inasmuch as the location of the first valve encountered can be difficult to identify preemptively, success of catheter advancement intraluminally will be enhanced if we begin by selecting longer, straighter veins or, alternatively, we introduce maneuvers in tortuous veins that will enhance the orientation among the vein, catheter, and valve.

Figure 1.

Venous catheter passage through veins and valves. A, Catheter within a straight vein, showing the catheter tip being directed toward the center of the valve os. B, Catheter within a tortuous vein, showing the tip being directed toward the junction of the valve leaflet and vein wall.

Fortunately, ideal vein selection is the same for the flick-spin technique as for other techniques: it is most desirable to start with a more distal vein and choose one that is more visible, is relatively straighter, has fewer visible valves, and, if possible, has tributary veins feeding into the main vein (to facilitate tethering of the vessel and lessen the chance that the vessel will be displaced or “roll” within soft surrounding tissues). Thereafter, linear traction should be placed on the vein to partially straighten and add tension to it so that its geography remains more stable during cannulation. This tension (if applied in moderation) will also will tend to diminish the lumen diameter so that the catheter will be directed more centrally up the vessel lumen as a result of multiple (or more extensive) contact points with the vessel wall (Figure 1, A), in contrast to intermittently contacting the vessel walls at curve points, which, in turn, will direct the catheter tip toward a vessel wall (Figure 1, B). Tension on the vein can be accomplished by flexing the wrist to add tension to vessels on the dorsum of the hand or by using the thumb of the operator’s nondominant hand to apply retraction to the skin (Figure 2, A-C), beginning distal and lateral to the point where the catheter and its obturator are to enter the skin. Skin traction, in turn, will straighten the vein (Figure 2, C). In conducting this step, it is important to not place the tension-generating thumb in direct line with the vessel because this will increase temptation to use the thumb (typically clad in a nonsterile glove) as a fulcrum for advancing the catheter into the patient’s tissues.

Figure 2.

Technique for using axial tension to straighten a vein. Tortuosity in a vein's course (A) can be lessened by applying axial tension to the vein. This can be accomplished by placing the thumb of the operator’s nondominant hand lateral and distal to the site of intended skin puncture (B) (ie, positioning that will avoid subsequent contact between the thumb and catheter). By pressing on the skin and pulling it toward the operator, the vein is straightened (C).

The catheter is then advanced off the obturator and into the vessel lumen using ordinary techniques. If during this maneuver catheter advancement is hindered by vessel tortuosity (Figure 3, A), catheter advancement can be coaxed along by either adjusting the aforementioned linear tension on the vessel or, alternatively, by applying gentle lateral pressure to the concavity of the vein’s curved course. This latter intervention will tend to realign the catheter’s axis and course with that of the vessel lumen’s course or, alternatively, reinforce the vessel wall so that perforation of the wall by the catheter tip is less likely (Figure 3, B).

Figure 3.

Lateral pressure to alter catheter tip direction within a tortuous vein. Once the catheter is in the lumen of a persistently tortuous or kinked vein (A), gentle lateral pressure can be applied to the vein’s concavity to improve co-registry of the axes of the catheter, vessel lumen, and vein os (B) and advancement of the catheter through the valve.

The flick-spin maneuver can be introduced either before the catheter tip has actually encountered an area of valve-rich vein or after empirical determination that a valve has interfered with further passage of the catheter within the vessel lumen. If the latter, the catheter (or catheter and obturator as a unit) should be pulled back approximately 1 to 2 mm or until external visual cues suggest that the catheter tip is no longer engaged with the valve. Thereafter, to institute the flick-spin maneuver, the catheter alone, or the catheter sliding along an incompletely removed obturator (which will provide structural support to prevent catheter kinking), can slowly be advanced along its axis and up the vessel lumen, provided distal tension on the vessel is maintained throughout the procedure (Figure 2, C and Figure 4, A). Simultaneous with advancement, the catheter is either spun around its axis or rocked back and forth on its axis (Figure 4, A). Additionally, the index finger of the operator’s nondominant hand is used to flick the vein (or skin overlying the vein) back and forth near the point overlying the assumed tip of the catheter. Used in concert, vessel tension (with or without intermittent lateral pressure to curves in the vessel’s course) along with catheter spinning and flicking the vein and skin (and hence the tip of the catheter within the vein) improve successful negotiation of the catheter through the valve without fracturing or rupturing the vessel wall (Figure 4, B and C). When successful, the catheter can then be advanced to its maximal length within the vessel (Figure 4, C), as would be the case with any other vessel.

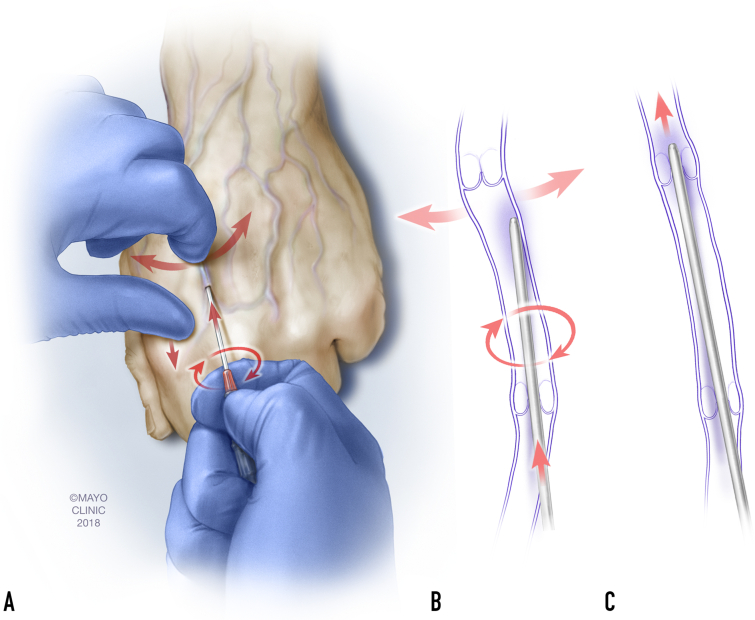

Figure 4.

Flick-spin maneuver. The flick-spin maneuver requires (A) using the thumb of the nondominant (shown as left) hand to apply tension to the skin nearby the tortuous vein and thereby straighten it. Thereafter, the dominant (shown as right) hand manipulates the catheter. Specifically, the index finger, third finger, and palm of the operator’s dominant hand are used to stabilize the obturator. Next, the dominant thumb is used to either spin the catheter around the axis of the obturator (shown) or rotate it back and forth (not shown) while the entirety of the dominant hand advances the catheter and slides it off the obturator and into the vessel lumen. Simultaneously, the index finger of the nondominant hand gently flicks the skin back and forth at the level of the catheter tip (A and B), coaxing the tip through any valves it may encounter (C).

A word of caution is in order regarding assessment of whether venous cannulation has been successful. In the most valve-dense peripheral veins, it is possible to have the tip of the catheter pass through one or more valves, only to come to rest beneath the leaflet of yet another valve (Figure 1, B). As such, there may be minimal blood return and no free flow of blood from a recently placed catheter. The latter can often be resolved simply by retracting the catheter by 1 to 2 mm or more, which may ensure either free return of blood or the free passage of fluids under minimal (eg, gravitational) pressure. Another possibility is that the catheter tip has come to rest in a small “lock” involving 2 valves minimally proximal and distal to the catheter tip (Figure 5, A). If this is the case, the first valve encountered will be partially obstructed by the catheter, and any negative pressure applied to the catheter lumen (eg, involving syringe aspiration) will simply serve to seal the downstream valve and collapse the vein (Figure 5, A). Thus, blood flow into the intervalvular vein lumen will cease, and no position-confirming blood will flow into the catheter. In contrast, it is often possible to test the assumption that a lock situation has occurred, and simultaneously open flow through the downstream valve, simply by injecting a small amount of physiologic salt solution under gravitational (from an intravenous line) or gentle supergravitational (from a syringe) pressure to flush open the valve (Figure 5, B). Thereafter, the obstructing valve will typically remain open as long as there is flow (eg, from intravenous fluids) through it.

Figure 5.

Intervalvular “lock”. A successfully placed catheter may eventually come to rest with its tip between 2 valves in close proximity. In this instance (A), the catheter may partially occlude the initial valve (V1), and negative pressure from aspiration of the catheter may close the subsequent valve (V2), resulting in a lock condition. In contrast, the pressure and flow of blood or fluids at either gravitational (intravenous fluids) or supergravitational (from a syringe) pressures may flush open the downstream (V2) valve (B). The valve will typically remain open as long as there is sufficient flow (eg, through intravenous fluids) through it.

In my experience, the described flip-spin technique has been successful during hundreds of otherwise failed vein cannulation attempts, typically to the surprise and amusement of patients, students, and seasoned clinicians alike.

Footnotes

Potential Competing Interests: The author reports no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ludbrook J. Functional aspects of the veins of the legs. Am Heart J. 1962;64(5):706–713. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(62)90257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caggiati A., Phillips M., Lametschwandtner A., Allegra C. Valves in small veins and venules. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32(4):447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caggiati A. The venous valves of the lower limbs. Phlebolymphology. 2013;20(2):87–95. [Google Scholar]