Abstract

Objective:

To examine the relationship between hospital outcomes and expenditures in patients undergoing bariatric surgery in the United States

Summary Background Data:

As one of the most common surgical procedures in the United States, bariatric surgery is a major focus of policy reforms aimed at reducing surgical costs. These policy mechanisms have made it imperative to understand the potential cost savings of quality improvement initiatives.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective review of 38,374 Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgery between 2011 and 2013. We ranked hospitals into quintiles by their risk- and reliability-adjusted post-operative serious complications. We then examined the relationship between upper and lower outcome quintiles with risk-adjusted, total episode payments. Additionally, we stratified patients by their risk (low, medium, high) of developing a complication to understand how this impacted payment.

Results:

We found a strong correlation between hospital complication rates and episode payments. For example, hospitals in the lowest quintile of complication rates had average total episode payments that were $1,321 per patient less than hospitals in the highest quintile ($11,112 versus $12,433, P<0.005). Cost savings was more prominent amongst high risk patients where the difference of total episode payments per patient between lowest and highest quintile hospitals was $2,160 ($12,960 versus $15,120; P<0.005). In addition to total episode payment savings, hospitals with the lowest complication rates also had decreased costs for index hospitalization, readmissions, physician services and post-discharge ancillary care compared to hospitals with the highest complication rates.

Conclusions:

Medicare payments for bariatric surgery are significantly lower at hospitals with low complication rates. These findings suggest that efforts to improve bariatric surgical quality may ultimately help reduce costs. Additionally, these cost savings may be most prominent amongst the patients at the highest risk for complications.

Medicare payments for bariatric surgery are significantly lower at hospitals with low complication rates. Additionally, these costs savings may be most prominent amongst the patients at the highest risk for complications.

Introduction

As one of the most common surgical procedures performed in the United States1–3, bariatric surgery is a major focus of policy initiatives aimed at improving quality and reducing costs. There is a growing pressure from policymakers to hold hospitals (and their surgeon’s) accountable for costs of surgical episodes (e.g. bundled payments) as well as total spending for their populations (e.g. accountable care organizations.) These policy mechanisms have made it imperative to understand the potential costs savings of quality improvement and selective referral initiatives4–7. Thus, in addition to the self-evident goal of improving quality for these procedures, providers, payers and policy makers increasingly need to understand what impact quality of surgical care may have on costs8.

There is conflicting evidence about the relationship between quality and cost for surgical procedures. It is possible that high quality care requires more resources and therefore cost more to payers. For example, one report of Medicare beneficiaries undergoing major inpatient surgery found that hospitals with higher costs to payers were associated with better outcomes9. In contrast, delivering high quality care could reduce costs to payers, particularly if complications and associated expenditures are avoided10,11. Moreover, in the context of population health, it is unclear the extent to which targeting quality improvement initiatives aimed at high risk populations undergoing surgery can reduce overall costs12.

In this context, we designed a study to describe the association of hospital rates of complications for bariatric procedures and the total episode costs to payers. Such findings are timely as payers move toward value-based payment models and providers attempt to anticipate the financial impact of quality improvement initiatives.

Methods

Data Source and Population

From the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services we used data from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) File from 2011 to 2013. We used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to identify patients who underwent bariatric procedures (ICD-9-CM codes 43.89, 44.3, 44.31, 44.38, 44.39, 44.68, 44.95, 44.96, 44.97, 44.99, 44.5, 45.51, and 45.9) who also had a concurrent diagnosis code for morbid obesity (ICD9-CM codes 278.0, 278.01, 278.02, V77.8) as done in previous studies using administrative claims13–15. Patients with a diagnosis code for abdominal malignancies were excluded (ICD-9-CM codes 150.0–159.9 or 230.1–230.9.) In addition, we excluded bariatric operations that were revisions. Because no specific ICD-9-CM code exists for bariatric revisions, these cases defined as any bariatric procedures performed after an index bariatric operation using the same codes as listed above.

Hospitals were identified by their provider number in the MEDPAR file. Additional information about each hospital was obtained by linking the MEDPAR file with data from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey16. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan and deemed exempt due to use of secondary data.

Assessment of Hospital Quality

We used rates of serious complications within 30 days of the index operation as our primary outcome to identify high and low quality hospitals. To do so we first identified post-operative complications using ICD-9-CM codes as done in previous bariatric cohorts15,17. These included the following categories of complications: anastomotic, cardiac, genitourinary, hemorrhagic, neurologic, obstruction, post-operative shock, pulmonary, splenic injury, thromboembolic, wound infection and reoperation.

We then further identified serious complications as any of the above and prolonged length of stay >75th percentile for the specific procedure performed. We added this length of stay criteria as done in previous studies to give clinical face validity (i.e. that the complication had meaningful clinical impact) to the rate and make it more specific11,18.

Finally, hospitals were then placed in rank order by rates of serious complications and divided into ordinal quintiles. Rates of serious complications were both risk- and reliability adjusted described in detail below. “High Quality” hospitals were fined as those in the quintile with the lowest rates of serious complications. Similarly, those in the quintile with the highest complication rates were labeled, “Low Quality.”

Assessment of Hospital Payments

We used payment data from the MEDPAR file to understand if location of care – high quality versus low quality hospitals – was associated with any differences in costs. Because hospital charges have wide variation and do not reflect the actual expense to payers, we used actual hospital payments. Our total episode payment included the admission for the index operation up until 30 days after discharge. We abstracted data from inpatient, outpatient, carrier (i.e. physician), home health, skilled nursing facility, long stay hospital and durable medical equipment files. Payments were then collapsed into four separate categories: index hospitalization, readmissions, physician services and post-discharge ancillary care.

Payments were price-standardized to account for how hospitals are paid differently by Medicare based on their geography (i.e. to account for cost of living and variable wage index) and the type of setting in which they provide care (e.g. if they serve a disproportionate share of low income patients or participate in graduate medical education.) By removing these intended adjustments made by payers, the payment amounts allow for a better comparison of resource utilization in the two settings. Methods for price-standardization was performed based on original reports from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and techniques later described by the Dartmouth Institute19,20. The same approach has been used in multiple previous studies to compare payments in Medicare administrative claims among surgical cohorts10,21.

Statistical analysis

The overall goal of this analysis was to describe the relationship between hospital quality and costs to payers for bariatric procedures. The first step required us to accurately determine quality based on the rates of serious complications at each individual hospital. Because hospitals differ in the patient populations they care for and the proportion of different bariatric operations they perform, the rates of complications needed to be risk-adjusted. A multivariable logistic regression model that accounted for patient age, sex, race, comorbidities (as described by Elixhauser22 and Southern23) and operation type (e.g. laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, laparoscopic Roux-en-y gastric bypass, open Roux-en-y gastriectomy etc.) was used to calculate a risk-adjusted rate of serious complications for each hospital. To account for possible secular trends, the year of operation was also included in our regression model.

We also performed a reliability adjustment to account for random variation in observed outcomes. Because many hospitals may have lower case volumes, it may be difficult to determine if the observed outcomes at these centers truly reflect the quality they provide or “statistical noise” (i.e. chance). Our approach to reliability adjustment that accounts for “statistical noise” has been previously described17,24–26. Briefly, this technique uses hierarchical modeling and empirical Bayes estimates to “shrink” lower volume hospitals toward the overall population mean proportionally to the strength of their statistical signal (i.e. their surgical volume.) Thus, our final quintiles to identify high and low quality hospitals were based on risk- and reliability-adjusted outcomes.

After identifying high and low quality hospitals, we compared them with respect to patient and hospital characteristics using X2 and Wilcoxon rank sum tests as appropriate. We then compared Medicare payments. To account for their non-parametric distribution, payments were log transformed. In addition to total episode payments, we also assessed the individual payment components (index admission, readmission, physician services, post-discharge ancillary care) to understand possible sources of differences. We also sought to understand payments at high and low quality hospitals for different patient populations. Based on the same multivariable logistic regression model described above for risk-adjustment, patients were divided into quintiles based on their pre-operative risk of developing a complication. Patients in the quintile most likely to develop a complication were labeled “High Risk.” Similarly, those in the quintile that were least likely to develop a complication were labeled, “Low Risk.” We then compared payments for “High Risk” and “Low Risk” quintiles of patients at both high and low quality hospitals.

Analyses were performed using STATA 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas.) All tests were two sided and significance was determined by a value of <0.05.

Results

Characteristics of patients treated at high and low quality hospitals are summarized in Table 1. Patients treated at high quality hospitals were on average older (age - 55.2 versus 54.3; p <0.001) compared to patients at low quality hospitals. There was no difference between the two groups with respect to gender (% male - 25.6 versus 25.6; P=0.99). For the majority of comorbidities identified in this study, there were no statistically significant differences. The majority of patients (81.3% in low quality hospitals and 79.3% in high quality hospitals) had at least 2 or more comorbid conditions. The average rate of serious complications for patients treated at low quality hospitals was higher compared to high quality hospitals (4.8% versus 1.9%; p<0.001.)

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| All Patients | Low Quality Hospitals |

High Quality Hospitals |

p-value (low vs high quality) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 38,347 | 8,285 | 10,851 | |

| Age (mean, years) | 55.02 | 54.33 | 55.23 | <.0001 |

| Male (%) | 26.03 | 25.60 | 25.59 | 0.990 |

| White (%) | 77.00 | 73.13 | 77.67 | <.0001 |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 75.76 | 75.72 | 76.79 | 0.082 |

| Diabetes | 46.73 | 45.87 | 47.14 | 0.080 |

| Depression | 29.44 | 27.82 | 29.55 | 0.009 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 26.89 | 27.64 | 25.40 | 0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 16.49 | 15.78 | 15.79 | 0.983 |

| Liver disease | 12.66 | 15.38 | 12.94 | <.0001 |

| Psychoses | 7.14 | 7.66 | 6.97 | 0.067 |

| Deficiency Anemias | 6.10 | 8.11 | 5.11 | <.0001 |

| Renal failure | 6.04 | 7.64 | 5.09 | <.0001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 5.33 | 6.13 | 4.17 | <.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 5.26 | 5.96 | 4.89 | 0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3.34 | 3.46 | 2.88 | 0.022 |

| Valvular disease | 1.74 | 1.85 | 1.62 | 0.240 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.73 | 1.68 | 1.73 | 0.771 |

| Coagulopthy | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.565 |

| Paralysis | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 0.005 |

| Elixha user #of Comorbidities (%) | 0.002 | |||

| 0 | 3.97 | 3.67 | 3.93 | 0.356 |

| 1 | 15.45 | 15.02 | 16.77 | <.001 |

| ≥2 | 80.58 | 81.32 | 79.30 | <.001 |

| Type of Operation | <.0001 | |||

| Laparoscopic Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass | 63.19 | 65.27 | 62.35 | <.0001 |

| Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy | 16.39 | 14.71 | 17.84 | <.0001 |

| Laparoscopic Adjustable Band Placement | 16.16 | 14.34 | 16.71 | <.0001 |

| Other | 4.26 | 5.67 | 3.10 | <.0001 |

High and low quality hospitals overall did have multiple differences in their hospital characteristics (Table 2.) For example, compared to low quality hospitals, the high quality hospitals were more likely to have for-profit ownership (28.3% versus 17.1%; p=0.04), <250 beds in size (40.6% versus 16.9%; p=0.001) and fewer number of operating rooms (21.9 versus 29.0; p=0.04). They had no difference in their geographic distribution or their nurse staffing ratios.

Table 2.

Hospital characteristics of all hospitals, high complication and low complication quintiles

| All hospiLais | Low Quality Hospitals |

High Quality Hospitals |

p-value (low vs high quality) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of hospitals | 531 | 106 | 107 | |

| No. of patients | 38,347 | 8,285 | 10,851 | |

| Ownership (%) | ||||

| For-Profit | 18.86 | 17.07 | 28.32 | 0.045 |

| Non-Profit | 71.58 | 69.78 | 65.79 | |

| Other | 9.56 | 13.16 | 5.89 | |

| Bed Size (%) | ||||

| <250 beds | 26.52 | 16.86 | 40.64 | 0.001 |

| >250 to <500 beds | 39.51 | 38.32 | 28.56 | |

| >500 beds | 33.97 | 44.82 | 30.80 | |

| Geographic Region (%) | ||||

| Northeast | 18.86 | 19.66 | 17.27 | 0.057 |

| Midwest | 25.64 | 31.88 | 24.82 | |

| South | 40.82 | 37.18 | 44.96 | |

| West | 14.68 | 11.29 | 12.95 | |

| Additional Oiaracteristics | ||||

| Teaching Hospital (%) | 66.56 | 82.44 | 59.74 | 0.002 |

| No. of operating rooms | 26.02 | 29.03 | 21.91 | 0.036 |

| Nurse Ratio | 8.26 | 8.37 | 8.63 | 0.444 |

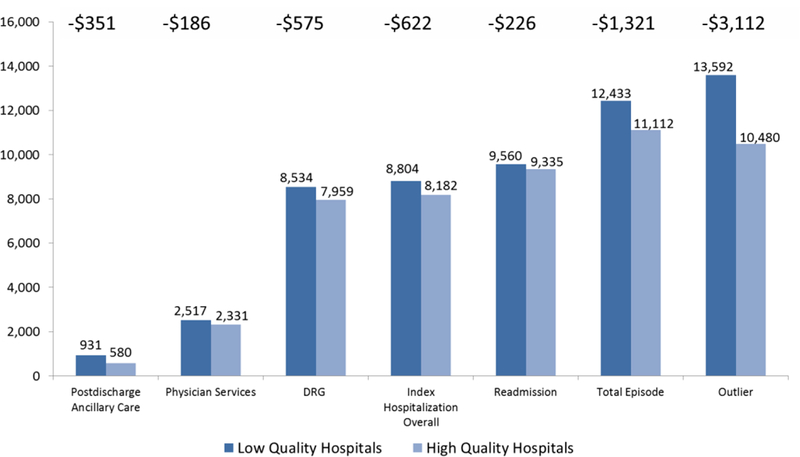

There was a strong association with high quality hospitals and lower Medicare payments. For example, average total episode payments for bariatric procedures at high quality hospitals were $1,321 per patient less compared to low quality hospitals ($12,433 versus 11,112; p< 0.0001). Analysis of each payment component (index hospitalization, physician services, readmission, post-discharge ancillary care), yielded similar differences (Figure 1 and Table 3.)

Figure 1.

Payment Components for Bariatric Procedures at High and Low Quality Hospitals

Table 3.

Payments for Bariatric Surgery at Low and High Quality Hospitals

| Payment Category ($) | Low Quality Hospital | High Quality Hospitals | Difference In Payments | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index Hospitalization OVerall | 8.804 | 8,182 | −622 | 0.001 |

| DRG | 8.534 | 7,959 | −575 | <.0001 |

| Outlier | ||||

| Proportion with Payment (%) | 1.4 | 1.8 | ||

| Average Payment when Present | 13,592 | 10,480 | −3,112 | 0.250 |

| Average Payment Overall | 269 | 223 | −47 | 0.756 |

| Physician services | 2,517 | 2,331 | −186 | 0.004 |

| Readmission | ||||

| Proportion with Payment (%) | 5.9 | 3.2 | ||

| Average Payment when Present | 9,560 | 9,335 | −226 | 0.905 |

| Average Payment Overall | 601 | 309 | −292 | 0.008 |

| Postdischarge ancillary care | ||||

| Proportion with Payment (%) | 56.9 | 49.6 | ||

| Average Payment when Present | 931 | 580 | −351 | <.0001 |

| Average Payment Overall | 511 | 291 | −220 | <.0001 |

| Total episode | 12,433 | 11,112 | −1,321 | <.0001 |

*Difference in standardized & case-mix (risk) adjusted 30-day episode payments. Hospitals quality represents hospital ranked into quintiles by their risk- and relieablity-adjusted rates of serious complications. Low Quality Hospitals representing the quintile of hospitals with the highest complication rates.

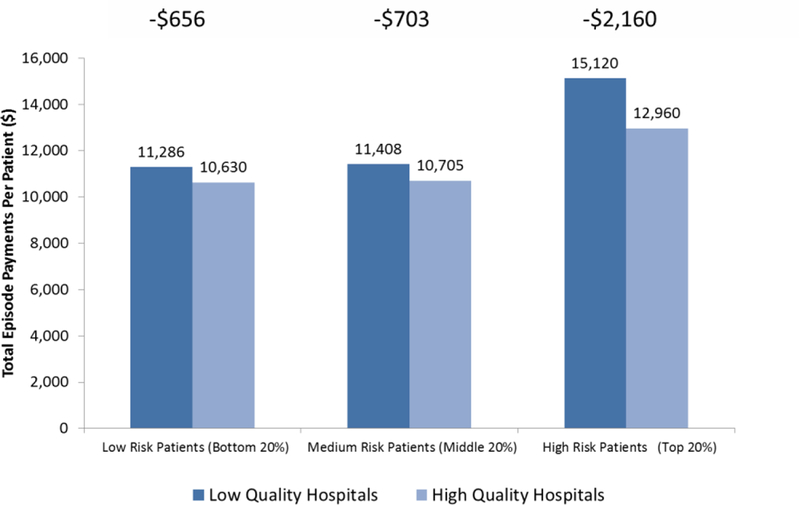

In sub-group analyses by patient risk, high quality hospitals were associated with lower Medicare payments across all quintiles of patient risk (Figure 2). For example, low risk patients treated at high quality hospitals cost on average $656 less than low risk patients treated at low quality hospitals (p-value). The difference was more prominent among high risk patients where the difference in payments per patient between high and low quality hospitals was $2,160 ($12,960 versus 15,120; p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Total Episode Costs For Bariatric Procedures at High and Low Quality Hospitals Stratified by High and Low Risk Patient Groups

Discussion

This study of hospital quality and Medicare expenditures for bariatric surgery had two principle findings. First, we found a strong correlation between high quality hospitals and lower payments from Medicare. This implies that reducing rates of complications for bariatric surgery may result in significant savings for payers. Second, we found that cost difference between high and low quality hospitals was most prominent amongst patients who were at high risk for developing complications. Thus, a second costs saving strategy for bariatric surgery may be selective referral of high risk patients to high quality centers. Taken together, this study supports emerging policy shifts toward value-based and bundle payment models by demonstrating the association of high quality care with lower payer costs.

Multiple previous studies have attempted to describe the relationship between hospital quality and costs to payers. A major limitation of previous reports associating high quality care with higher costs was the inability to accurately assess payments from the payer perspective. Specifically, prior studies lack “price-adjustment” that fully account for intended subsidies to hospitals that participate in graduate medical education or care for a disproportionate share of low-income patients9,27,28. More recent studies that directly account for these same intended payment adjustments have been able to demonstrate an association of high quality care with lower costs for non-bariatric inpatient operations10,11. Our present study adds to the latter group by also demonstrating that hospitals providing high quality care (i.e. those with lower complication rates) are associated with lower costs to payers for one of the most common elective operations: bariatric surgery.

Whether or not hospitals are financially incentivized to improve quality has also been a matter of debate. For example, one analysis of administrative claims in a 12 hospital non-profit health system found that surgical patient admissions with complications had higher contribution margins (i.e. hospital profit)29. The authors ominously concluded that, “many hospitals have the potential for adverse near-term financial consequences for decreasing postsurgical complications.” In contrast, a review of a single institution registry for surgical admissions demonstrated that patients with higher complications actually returned lower profit margins to the hospitals30. This study adds to the debate by demonstrating from a payer perspective, hospitals with lower complication rates provide care with lower Medicare expenditures.

This present study should be interpreted within the context of multiple limitations. First, we used administrative claims data that may not accurately capture complications. To limit this potential coding bias, we used codes described in the Complications Screening Program that are significantly more sensitive and specific for capturing inpatient complications31,32. In addition, we added a length of stay criteria to increase the specificity of our outcomes33. Second, by using Medicare data our study did not include many younger patients who undergo bariatric procedures. While important to understand this younger population as well, by using Medicare data this study evaluates the largest payer in the country who is actively piloting value-based payment models34. As such, this likely reflects the population where our findings of costs and quality will be first applied to inform future alternative payment models. Finally, by utilizing Medicare data we were not able to assess the possible impact centers of excellence may have on payment. Because Medicare restricted payment to centers of excellence up until 2013 (the final year of this study), hospitals without centers of excellence designation were not available as a possible control group. Nonetheless, more than 88% of bariatric procedures are currently performed at centers of excellence35 and thus our findings are generalizable to the majority of bariatric surgery providers.

Several implications for both policy and practice related to bariatric surgery emerge from our findings. First, this study helps align the goals of quality improvement and cost savings for bariatric surgery. Building on previous reports demonstrating that payers carry the financial risk of poor surgical quality36, our findings should encourage payers to support and even incentivize hospitals in their quality improvement initiatives. Numerous quality improvement initiatives in bariatric surgery exists including state-wide collaboratives37 that payers may consider requiring or even subsidizing. More recent evidence studying video of seasoned bariatric surgeons found that the wide variation in their technical skill correlated with rates of post-operative complications38, suggesting surgeon skill as another possible target for quality improvement. Second, our findings provide new insight into how patient risk of developing complications influences costs. While it is self-evident that patients at high risk for complications may be more costly, the results here reveal that preventing complications in this group actually represents a large opportunity for cost savings. Thus, as payers and healthcare administrators target opportunities for cost savings they may begin by supporting quality improvement programs at hospitals with the highest risk patients. Alternatively, they may consider selective referral for this high risk population. Finally, as policy makers continue to move toward value based payment models (e.g. bundle payments, accountable care organizations) their rationale appears justified. In addition to improving patient care, our study suggests that providing high quality care can be achieved at lower costs to payers.

Conclusion

In summary, Medicare payments for bariatric surgery are significantly lower at hospitals with low complication rates. These findings suggest that efforts to improve bariatric surgical quality may ultimately help reduce costs. Additionally, these costs savings may be most prominent amongst the patients at the highest risk for complications.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding:

AAG is supported through grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant #: 5K08HS02362 and P30HS024403) and a Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award (CE-1304–6596).

AMI receives funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Department of Veterans Affairs in his role as a Clinical Scholar.

JBD is supported through grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grant #: 1T32DK108740 and 5R21DK100710.) He also has equity interest in Arbor Metrix, which had no role in the analysis herein.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

JRT has no disclosures.

Contributor Information

Andrew M. Ibrahim, Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Amir A. Ghaferi, Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Jyothi R. Thumma, Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Justin B. Dimick, Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan..

References

- 1.Nguyen NT, Vu S, Kim E, Bodunova N, Phelan MJ. Trends in utilization of bariatric surgery, 2009–2012. Surgical endoscopy December 10 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santry HP, Gillen DL, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. Jama October 19 2005;294(15):1909–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young MT, Jafari MD, Gebhart A, Phelan MJ, Nguyen NT. A decade analysis of trends and outcomes of bariatric surgery in Medicare beneficiaries. Journal of the American College of Surgeons September 2014;219(3):480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schirmer B, Jones DB. The American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: establishing standards. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons August 2007;92(8):21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Share DA, Campbell DA, Birkmeyer N, et al. How a regional collaborative of hospitals and physicians in Michigan cut costs and improved the quality of care. Health affairs April 2011;30(4):636–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pratt GM, McLees B, Pories WJ. The ASBS Bariatric Surgery Centers of Excellence program: a blueprint for quality improvement. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery Sep-Oct 2006;2(5):497–503; discussion 503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollenbeak CS, Rogers AM, Barrus B, Wadiwala I, Cooney RN. Surgical volume impacts bariatric surgery mortality: a case for centers of excellence. Surgery November 2008;144(5):736–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birkmeyer NJ, Birkmeyer JD. Strategies for improving surgical quality--should payers reward excellence or effort? The New England journal of medicine February 23 2006;354(8):864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor DH Jr., Whellan DJ, Sloan FA. Effects of admission to a teaching hospital on the cost and quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries. The New England journal of medicine January 28 1999;340(4):293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birkmeyer JD, Gust C, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer NJ, Skinner JS. Hospital quality and the cost of inpatient surgery in the United States. Annals of surgery January 2012;255(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scally CP, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Impact of Surgical Quality Improvement on Payments in Medicare Patients. Annals of surgery August 2015;262(2):249–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nathan H, Dimick JB. Opportunities for Surgical Leadership in Managing Population Health Costs. Annals of surgery 2016: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001759. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Nguyen NT, Paya M, Stevens CM, Mavandadi S, Zainabadi K, Wilson SE. The relationship between hospital volume and outcome in bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Annals of surgery October 2004;240(4):586–593; discussion 593–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livingston EH. Bariatric surgery outcomes at designated centers of excellence vs nondesignated programs. Archives of surgery April 2009;144(4):319–325; discussion 325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimick JB, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD. Bariatric surgery complications before vs after implementation of a national policy restricting coverage to centers of excellence. Jama February 27 2013;309(8):792–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Hospital Association. AHA annual survey database http://www.ahadataviewer.com/book-cd-products/AHA-Survey., Accessed June 6, 2016.

- 17.Krell RW, Finks JF, English WJ, Dimick JB. Profiling hospitals on bariatric surgery quality: which outcomes are most reliable? Journal of the American College of Surgeons October 2014;219(4):725–734 e723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osborne NH, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Association of hospital participation in a quality reporting program with surgical outcomes and expenditures for Medicare beneficiaries. Jama February 3 2015;313(5):496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottlieb DJ, Zhou W, Song Y, Andrews KG, Skinner JS, Sutherland JM. Prices don’t drive regional Medicare spending variations. Health affairs Mar-Apr 2010;29(3):537–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottlieb DJ, Zhou W, Song Y, Andrews KG, Skinner J, Sutherland JM. Technical Report: A Standardized Method for Adjusting Medicare Expenditures for Regional Differences in Prices 2010; http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/papers/std_prc_tech_report.pdf. Accessed 25 September, 2015.

- 21.Ibrahim AM, Hughes TG, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Association of Hospital Critical Access Status With Surgical Outcomes and Expenditures Among Medicare Beneficiaries. Jama May 17 2016;315(19):2095–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Medical care January 1998;36(1):8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Medical care April 2004;42(4):355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones HE, Spiegelhalter DJ. The Identification of “Unusual” Health-Care Providers From a Hierarchical Model. Am Stat August 2011;65(3):154–163. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dimick JB, Staiger DO, Birkmeyer JD. Ranking hospitals on surgical mortality: the importance of reliability adjustment. Health services research December 2010;45(6 Pt 1):1614–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grenda TR, Krell RW, Dimick JB. Reliability of hospital cost profiles in inpatient surgery. Surgery August 19 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Koenig L, Dobson A, Ho S, Siegel JM, Blumenthal D, Weissman JS. Estimating the mission-related costs of teaching hospitals. Health affairs Nov-Dec 2003;22(6):112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mechanic R, Coleman K, Dobson A. Teaching hospital costs: implications for academic missions in a competitive market. Jama September 16 1998;280(11):1015–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eappen S, Lane BH, Rosenberg B, et al. Relationship between occurrence of surgical complications and hospital finances. Jama April 17 2013;309(15):1599–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Healy MA, Mullard AJ, Campbell DA Jr., Dimick JB. Hospital and Payer Costs Associated With Surgical Complications. JAMA surgery May 11 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Iezzoni LI. Assessing quality using administrative data. Annals of internal medicine October 15 1997;127(8 Pt 2):666–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weingart SN, Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, et al. Use of administrative data to find substandard care: validation of the complications screening program. Medical care August 2000;38(8):796–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livingston EH. Procedure incidence and in-hospital complication rates of bariatric surgery in the United States. American journal of surgery August 2004;188(2):105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajkumar R, Press MJ, Conway PH. The CMS Innovation Center--a five-year self-assessment. The New England journal of medicine May 21 2015;372(21):1981–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gebhart A, Young M, Phelan M, Nguyen NT. Impact of accreditation in bariatric surgery. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery Sep-Oct 2014;10(5):767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dimick JB, Weeks WB, Karia RJ, Das S, Campbell DA Jr., Who pays for poor surgical quality? Building a business case for quality improvement. Journal of the American College of Surgeons June 2006;202(6):933–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell DA Jr., Englesbe MJ, Kubus JJ, et al. Accelerating the pace of surgical quality improvement: the power of hospital collaboration. Archives of surgery October 2010;145(10):985–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O’Reilly A, et al. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. The New England journal of medicine October 10 2013;369(15):1434–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]