Abstract

Hypothesis:

For experienced adult cochlear implant (CI) users who have reached a plateau in performance, a clinician-guided aural rehabilitation (AR) approach can improve speech recognition and hearing-related quality of life (QOL).

Background:

A substantial number of CI users do not reach optimal performance in terms of speech recognition ability and/or personal communication goals. Although self-guided computerized auditory training programs have grown in popularity, compliance and efficacy for these programs are poor. We propose that clinician-guided AR can improve speech recognition and hearing-related QOL in experienced CI users.

Methods:

Twelve adult CI users were enrolled in an 8-week AR program guided by a speech-language pathologist and audiologist. Nine patients completed the program along with pre-AR and immediate post-AR testing of speech recognition (AzBio sentences in quiet and in multi-talker babble, Consonant-Nucleus-Consonant words), QOL (Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire, Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults/Elderly, and Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale), and neurocognitive functioning (working memory capacity, information-processing speed, inhibitory control, speed of lexical/phonological access, and nonverbal reasoning). Pilot data for these 9 patients are presented.

Results:

From pre-AR to post-AR, group mean improvements in word recognition were found. Improvements were also demonstrated on some composite and subscale measures of QOL. Patients who demonstrated improvements in word recognition were those who performed most poorly at baseline.

Conclusions:

Clinician-guided AR represents a potentially efficacious approach to improving speech recognition and QOL for experienced CI users. Limitations and considerations in implementing and studying AR approaches are discussed.

Keywords: Auditory training, Aural rehabilitation, Cochlear implants, Cognition, Speech Recognition, Quality of Life

Introduction

Cochlear implants (CIs) are a valuable rehabilitation option for adults with moderate-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss. CIs restore auditory input and some capacity for spoken language communication. However, extremely broad variability in speech recognition outcomes persists (1–4). In fact, 10 to 50% of patients can be considered “poor performers” based on studies reporting 13% of adult CI users scoring less than 10% correct words in sentences when tested in quiet (5) and that less than half of CI users effectively communicate via telephone (6). After a period of adaptation to the new electrical input delivered by the devices, adult CI users typically reach a plateau in performance by 18 to 24 months after implantation (5–7). Many patients express dis-satisfaction with their performance plateau, particularly in more challenging listening conditions (e.g., noisy environments, communicating in multi-talker settings) (8).

In evaluating a CI user who is a “poor performer”, the surgeon will typically obtain imaging with computed tomography to ensure that the electrode array is positioned appropriately, and the audiologist will re-program the device. In some cases, a hardware integrity check will be performed. Many times these approaches do not reveal significant abnormalities for which a revision surgery or dramatic modifications in device programming are warranted. Patients are then often provided with resources that might be beneficial, such as patient support groups or educational materials about self-guided auditory training options. However, many patients remain frustrated by the lack of structured rehabilitative interventions (8).

Clinician-guided aural rehabilitation is not standard practice in many CI centers, likely secondary to poor reimbursement for audiologists and a lack of speech-language pathologist (SLP) involvement on the team, in contrast to (re)habilitation in pediatric CI users. In addition, the indications for recommending rehabilitation in this population remain unclear. As a result, adult CI users are often encouraged to seek out self-guided training approaches, such as listening to audiobooks or using computerized auditory training programs that can be completed at home. Current popular programs include AngelSound (modified from the original Computer-Assisted Speech Training program and Sound and Way Beyond), Sound Scape, and the Listening Room and computerized CLIX activities (9,10). Additional programs originally used for patients with milder degrees of hearing loss are sometimes recommended to CI patients, such as Computer-Assisted Speech Perception (11), Listening and Communication Enhancement (12), Speech Perception Assessment and Training System (13), and Read My Quips (Sense Synergy, Inc., Bodega Bay, CA). Most of these programs consist of relatively “analytic” bottom-up approaches, with presentations of speech stimuli to which the patient provides a repetition response and receives feedback, although some programs incorporate higher-level “synthetic” top-down approaches focused on communication strategies and cognitive functions. It is unclear whether these programs typically result in benefits that generalize to better speech recognition and overall communicative functioning, including improvements in hearing-related quality of life (QOL) (14). Moreover, patient-reported compliance with these programs is reported as low as 30% (8,14,15). Even in structured research studies of computerized home training programs, adult CI users have demonstrated the need for assistance from research personnel for technical support and program troubleshooting, or they have reported that the programs were too difficult, frustrating, or tedious (16).

Because of these limitations in self-guided computerized training approaches, we have focused on developing a clinician-guided aural rehabilitation program at our institution. We propose that the support from one-on-one interactions with a clinician during therapeutic rehabilitation sessions promotes individualization of treatment and greater patient compliance with therapy. Specifically, SLPs and audiologists have received specialized training in the areas of language and cognition, and thus they provide the ideal skillset to assist patients in scaffolding learning during the auditory rehabilitation and training process.

Here we present “proof-of-concept” pilot data from an ongoing project investigating the benefits of a clinician-guided aural rehabilitation (AR) program in experienced adult CI users. This study included adult CI users from our institution with at least 18 months of CI experience who were not content with their performance based on self-report to their audiologists. Participants underwent baseline evaluations of aided detection thresholds, speech recognition, hearing-related QOL questionnaires, and assessments of neurocognitive functioning (e.g., information-processing speed, working memory capacity, inhibitory control). For the ongoing project, assessments of neurocognitive functions are being included to determine whether baseline neurocognitive functions impact the efficacy of AR for individual patients, whether these functions change as a result of AR, and whether any changes in neurocognitive functions relate to changes in speech recognition. Participants enrolled in a program of 8 weekly one-hour sessions with an SLP and Audiologist, during which device counseling and in-person auditory training therapy was performed. Following completion of therapy, repeat assessments of speech recognition, QOL, and neurocognitive functions were performed. Recognizing that our sample is small, conclusions should be made cautiously. Nonetheless, we propose that the feasibility of this clinician-guided approach has been demonstrated, the early results are encouraging, and a number of limitations and considerations of AR research approaches have been identified that are worth discussing for future designs of AR studies.

Four general hypotheses were tested: (1) As a group, participants would demonstrate an improvement in speech recognition performance from pre-AR to post-AR. (2) As a group, participants would demonstrate improvements in hearing-related QOL from pre-AR to post-AR. (3) Participants who showed the largest AR-related gains in speech recognition would be those who had the most to gain (i.e., started with the worst performance). (4) Participants who showed the largest AR-related gains in speech recognition would be those who demonstrated the poorest pre-AR neurocognitive functioning, because these individuals would have the most to gain from AR.

Methods

Participants

Twelve post-lingually deaf adults who were experienced CI users from the Otolaryngology Department of The Ohio State University’s Neurotology Division were enrolled. Nine participants completed all testing and clinician-guided AR sessions. Participants who inquired about resources, did not make improvements with recommended self-guided training, or reported dissatisfaction with their CI performance were recruited by their audiologists. See Supplemental Digital Content for inclusion and exclusion criteria and details regarding enrolled participants.

Equipment and Materials

Testing took place at the Eye and Ear Institute (EEI) of The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and in the Speech-Language-Hearing Clinic in the Department of Speech and Hearing Science of The Ohio State University, using sound-proof booths. Auditory stimuli were presented soundfield by a speaker placed one meter in front of the participant at zero degrees Azimuth. See Supplemental Digital Content for further details.

Speech Recognition

Speech recognition tasks were presented using recorded material in the soundfield. Repeated baseline testing was performed between two and four times (mean 2.4 repeat baseline sessions of testing) on different days during a one-month period for each participant using different lists of each speech recognition measure, except for two participants who only had a single baseline session of speech recognition testing in the pre-AR period as a result of participant scheduling conflicts. Within two weeks after completion of AR, all participants except one were tested twice within a one-month period using repeat assessments of speech recognition; one participant completed post-AR speech recognition testing only once due to scheduling conflicts. Repeated baseline testing pre-AR and repeated post-AR assessments were performed to obtain several scores that could be averaged across lists to account for inter-list performance variability (17,18) and potential intra-subject testing variability (19). Based on the number of items administered during pre- and post-AR testing, 95% critical differences were computed to better interpret within-subject change and between-subject variability. This approach was based on that reported by Thornton and Raffin (20).

Speech recognition measures were chosen because they are widely used clinically, and they are typically challenging enough to avoid ceiling effects for most CI users during testing. For each test, stimuli were presented in the soundfiled at 60 dB SPL and participants were asked to repeat as much of the stimuli as they could. Three speech recognition measures were used: AzBio sentences in quiet, AzBio sentences in 10-talker babble, and Consonant-Nucleus-Consonant (CNC) words in quiet. See Supplemental Digital Content for details of these measures.

Hearing-Related QOL Measures

Three hearing-related QOL assessments were selected to measure self-reported QOL across factors associated with daily function and impairment related to hearing loss and/or cochlear implantation. Assessments were completed by participants at home by self-administration with no time limit, and responses were mailed back to the laboratory for scoring. These assessments consisted of the Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire (NCIQ), the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults/Elderly (HHIA/HHIE), and the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ). See Supplemental Digital Content for details regarding these measures.

Measures of Neurocognitive Functioning

Neurocognitive tasks were included in single sessions of pre-AR and post-AR assessment in the ongoing AR study. For the purposes of this preliminary report of 9 participants, data from these neurocognitive assessments were used only to examine whether those participants who demonstrated AR-related improvements in speech recognition differed in neurocognitive functioning, with the prediction that those with poorer neurocognitive functioning pre-AR would benefit the most from AR. Visual stimuli for neurocognitive tests were presented on paper or a touch screen monitor made by KEYTEC, INC., placed two feet in front of the participant. The following functions and measures were collected, with details outlined in the Supplemental Digital Content: verbal working memory capacity (digit span/object span/symbol span), inhibitory control and information-processing speed (Stroop task), nonverbal fluid reasoning (Raven’s Progressive Matrices), and speed of lexical access (lexical decision task).

General Approach

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Ohio State University. All participants provided informed, written consent, and were reimbursed $15 per hour of testing. Pre-AR testing of speech recognition and neurocognitive functioning was completed over a single 2-hour session, with frequent breaks to prevent fatigue. Additional repeat testing sessions for speech recognition alone were completed over approximately 30 minutes each. During testing, participants used their typical hearing prostheses, including any contralateral hearing aid.

Clinician-Guided AR Program

Participants were seen by the SLP (author CR) for one hour weekly for 8 weeks to complete therapy. Although treatment was individualized based on the SLP’s in-person functional assessments, a combination of analytic and synthetic training tasks was used for each participant, modeled after those described in the Adult Aural Rehabilitation Manual published by Cochlear Limited (21). All participants also received extensive counseling by the Audiologist for device troubleshooting and counseling about communication strategies for patient-specific goals for approximately 10 minutes during each training session (author JB).

Participants were given instruction for daily home practice of similar tasks, using live voice activities when communication partners were willing and available, as well as computer-based training that could be completed individually as needed (e.g., AngelSound). Each participant was instructed to complete 30 minutes of the assigned auditory training daily. Compliance with homework in this initial group of patients was followed informally by asking them about their practice patterns. Overall, patients verbally reported completion of some form of auditory training at home daily; however, the details of the activities and duration were not tracked closely.

Results

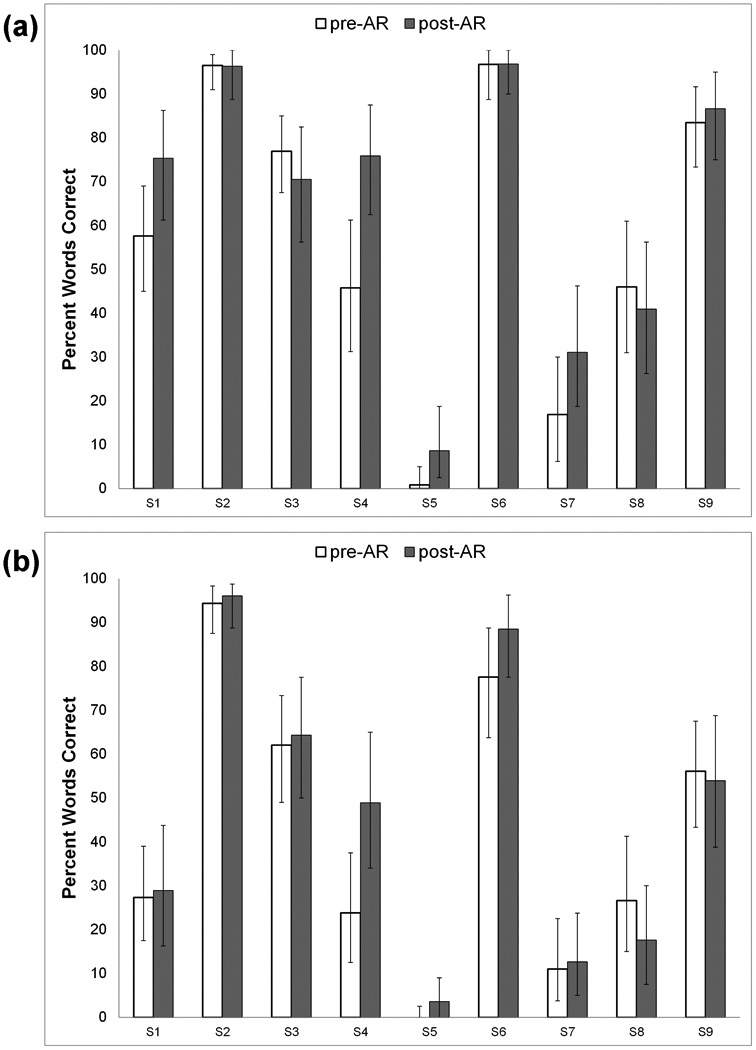

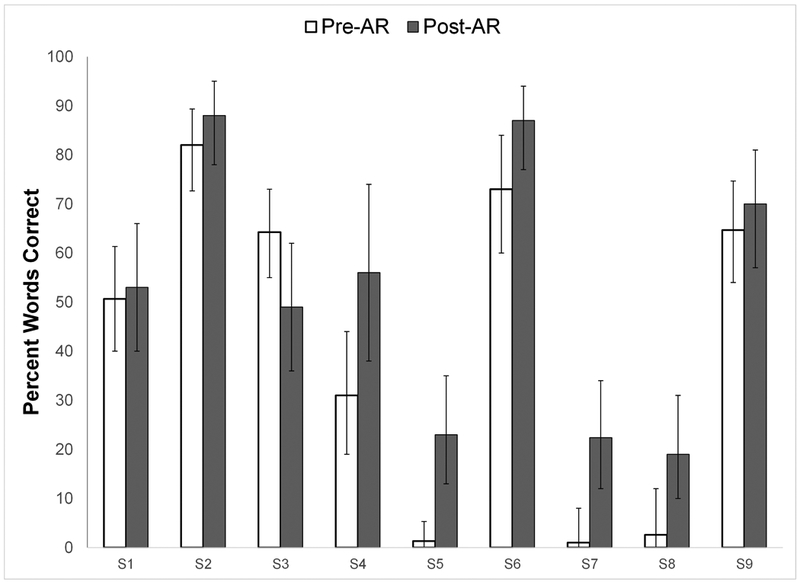

Individual participant scores for pre-AR (across multiple baseline assessments) and post-AR (across multiple assessments) speech recognition are plotted in Figures 1a (AzBio sentences in quiet), 1b (AzBio sentences in multi-talker babble), and 2 (CNC words in quiet). In order to determine the significance of observed differences in scores between pre- and post-AR speech recognition, 95% critical difference bars were plotted. Significant changes were determined by identifying improvement outside the determined 95% critical difference ranges of each score (i.e., where critical difference bars do not overlap). Group mean scores for pre-AR and post-AR speech recognition are shown in Table 1, along with results of the paired t-tests to address hypothesis #1, that CI users as a group would demonstrate significant improvements in speech recognition from pre-AR to post-AR.

Figure 1.

Pre- and post-aural rehabilitation (AR) mean scores for 9 individual subjects (S1 through S9) on (a) AzBio sentences (percent words correct) in quiet; and (b) AzBio sentences (percent words correct) in multi-talker babble. 95% critical differences for individual scores are shown as error bars.

Figure 2.

Pre- and post-aural rehabilitation (AR) mean scores for 9 individual subjects (S1 through S9) on CNC words (percent words correct) in quiet. 95% critical differences for individual scores are shown as error bars.

Table 1.

Group mean speech recognition scores for 9 CI users pre- and post-aural rehabilitation (AR). Results of paired t-tests are shown comparing group mean scores between pre- and post-AR sessions.

| Pre-AR | Post-AR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | t value | p value | |

| Speech Recognition | ||||||

| AzBio sentences in quiet (% words correct) | 57.9 | (34.0) | 64.7 | (30.9) | 1.72 | .124 |

| AzBio sentences in 10-talker babble (% words correct) | 42.1 | (31.9) | 46.0 | (33.0) | 1.25 | .246 |

| CNC words (% words correct) | 41.1 | (33.0) | 51.9 | (26.7) | 2.56 | .034 |

Based on 95% critical differences, participants S5 and S7 demonstrated significant improvements in CNC scores from pre- to post-AR, and the group as a whole demonstrated a significant improvement in mean CNC word score. Individual participant S4 demonstrated a significant improvement in AzBio sentences in quiet, but no individual participants demonstrated significant improvemenst in AzBio sentences in noise. Group mean scores on AzBio sentences in quiet and in multi-talker babble did not significantly improve, although the direction of change was positive in both cases from pre- to post-AR. To summarize, even in this small sample of 9 experienced adult CI users, clinician-guided AR resulted in significant improvements in CNC scores for two participants, along with a group improvement in mean CNC score.

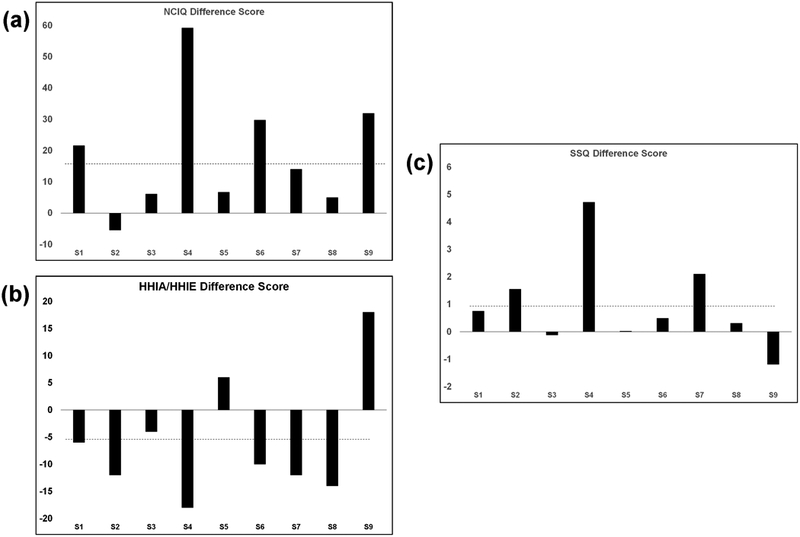

Differences in pre-AR to post-AR QOL for individual participants are shown in Figures 3a (NCIQ total), 3b (HHIA/HHIE total), and 3c (SSQ mean), along with the mean difference score for the group as demonstrated by the dotted lines. The individual participant plots demonstrate improvements in QOL measures for several individuals. Group mean scores for QOL measures are shown in Table 2, along with results of paired t-tests comparing pre-AR to post-AR QOL to address hypothesis #2, that clinician-guided AR would be associated with improvements in hearing-related QOL. The group as a whole showed a significant improvement on the mean NCIQ total score, a significant improvement on the HHIA/HHIE Emotional subscale, and a trend towards improvement on the Speech subscale of the SSQ.

Figure 3.

Difference scores from pre- to post-aural rehabilitation (AR) for 9 individual subjects (S1 through S9) on (a) the Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire (NCIQ, note that positive difference scores represent better quality of life); (b) the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults/Elderly (HHIA/HHIE, note that negative difference scores represent better quality of life); and (c) the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing scale (SSQ, note that positive difference scores represent better quality of life). Group mean difference scores are shown as dotted lines.

Table 2.

Group mean hearing-related quality of life scores for 9 CI users pre- and post-aural rehabilitation (AR). Results of paired t-tests are shown comparing group mean scores between pre- and post-AR sessions.

| Pre-AR | Post-AR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | t value | p value | |

| Hearing-related quality of life | ||||||

| Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire (total) | 165.0 | (37.0) | 183.9 | (45.2) | 2.89 | .020 |

| Physical | 54.8 | (14.8) | 58.4 | (15.2) | 1.53 | .164 |

| Psychological | 50.8 | (16.6) | 60.7 | (21.4) | 1.56 | .158 |

| Social | 59.4 | (15.2) | 64.7 | (9.7) | 5.93 | .124 |

| Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults/Elderly (total) | 56.9 | (23.5) | 51.1 | (24.7) | 1.54 | .163 |

| Emotional | 29.1 | (13.9) | 23.1 | (13.5) | 3.18 | .013 |

| Social | 27.8 | (13.8) | 28.0 | (12.0) | 0.06 | .954 |

| Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing (mean) | 3.4 | (1.4) | 4.4 | (2.1) | 1.69 | .129 |

| Speech | 3.0 | (1.4) | 4.3 | (2.0) | 2.1 | .069 |

| Spatial | 3.0 | (1.5) | 3.9 | (2.2) | 0.98 | .257 |

| Qualities | 4.5 | (2.4) | 5.3 | (2.5) | 1.69 | .134 |

Our final two hypotheses were that those participants who demonstrated the greatest AR-related speech recognition improvements would be those with the poorest baseline speech recognition (hypothesis #3), as well as those with the poorest baseline neurocognitive functions (hypothesis #4). Consistent with previous studies of auditory training, some participants showed improvements in speech recognition, while others demonstrated no change or even slight decrements in performance. To address these two hypotheses, focusing on CNC words, for which a significant group difference was identified above from pre-AR to post-AR, the group was split into those who demonstrated improvements of >10% words correct (N = 5) versus those who demonstrated smaller or no improvements (N = 4). This criterion of 10% was based on the approximate mean 95% critical difference score across word recognition scores for the 9 participants. Results of independent-samples t-test analyses comparing these two groups on baseline speech recognition performance are shown in Supplemental Digital Content (Table SDC2). Consistent with our hypothesis, the group who showed AR-related improvements in CNC word recognition started with baseline CNC word recognition that was significantly poorer than the group who did not show AR-related improvements. Although the samples were small, this finding suggests that CI users who demonstrate improvements in speech recognition tend to be those who begin with poorer performance.

To address hypothesis #4, the same two groups, those who showed substantial AR-related improvements in CNC word recognition versus those who did not, were compared on baseline neurocognitive performance, and results are shown in Supplemental Digital Content (Table SDC3). No significant differences were identified between baseline neurocognitive performance on these measures for these two groups.

Discussion

This ongoing study of clinician-guided AR aims to investigate the efficacy of AR to improve speech recognition and hearing-related QOL, and associated neurocognitive functions, for experienced adult CI users who are relatively poor performers or who are dissatisfied with their plateau in performance. Our preliminary results in a small group of 9 CI users suggest that there are benefits to speech recognition and QOL as a result of clinician-guided AR, but responses are highly variable. Exploratory analyses suggest that patients who respond well to AR are likely those who have the most to gain in baseline speech recognition performance.

Our early experience with this AR project over the past two years has revealed a number of challenges and limitations in conducting rehabilitation studies in CI users. We believe these challenges are worth discussing for those considering implementing AR approaches clinically and in research settings. First, selection of outcome measures is both critical and challenging. It is important to use measures that are clinically relevant and that avoid ceiling effects (i.e., too easy) and floor effects (i.e., too difficult). This choice is challenging, particularly when there is highly variable baseline performance among patients. Including measures across a range of difficulty partially overcomes this challenge when assessing within-individual changes from baseline to post-AR, but it does not overcome effects of broad inter-individual variability. Use of a speech recognition task that modifies the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) throughout testing to give a single SNR threshold value for each participant, such as the QuickSIN (22), might provide a better measure across a wide range of individual performance; however, this may be too difficult for some poor performers to provide meaningful results.

Next, outcome measures should be ecologically valid, meaning they should relate to the daily communicative demands placed on the patient. For that reason, we have focused on sentence recognition materials, specifically the AzBio sentences in quiet and in multi-talker babble. For sentence recognition, listeners can generally take advantage of top-down predictive language processing through sentence context, akin to what they likely do in daily communications. However, participants should not be tested repeatedly using the same sentence lists due to concern for learning of the lists, and inter-list performance variability becomes an issue, even though lists were developed to be relatively equivalent in difficulty (17). This problem became apparent during our repeated baseline assessments prior to AR; some patients demonstrated differences of up to 15% on AzBio sentence lists between baseline testing sessions, even though they were experienced CI users who should be at a plateau in performance. This problem is also apparent when examining Figures 1 and 2, where the 95% critical difference bars are relatively large for all speech recognition measures; this finding means that a change in speech recognition score must be quite large to be considered statistically significant. It is impossible to determine if this was a result of inter-list variability or day-to-day intra-individual performance variability for that patient (i.e. due to fatigue, wakefulness, effort). As a result, we have started including a questionnaire of wakefulness to include at each testing session, the Stanford Sleepiness Scale (23). Intra-individual performance variability does suggest, at minimum, that multiple baseline assessments should be incorporated into analyses.

Outcome measures should also be broad and encompass multiple domains of performance. As demonstrated here, some individuals may demonstrate improvements in QOL after AR even if they do not demonstrate improvements in speech recognition. This finding is consistent with studies suggesting only a weak relationship between speech recognition outcomes and QOL in CI users (24,25). In fact, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated correlations among hearing-specific QOL and speech recognition scores in CI users to be only on the order of r = .21 to .26 (25). Hearing-related QOL measures may capture valuable improvements as a result of AR that cannot be quantified with speech recognition measures. However, it may also be difficult to demonstrate significant improvements in QOL, and we do not know from the literature what degree of improvement on these QOL measures would be considered clinically relevant. More broadly, measures of listening effort (such as dual task methodology or pupillometry) may provide more sensitive assessments of listening performance. Unfortunately, current measures of listening effort are tedious and not practical for clinical use.

Fourth, a definitive evaluation of the efficacy of clinician-guided AR in adult CI users will require a prospective, randomized trial with control participants. Although unlikely, our AR participants may have shown benefits to word recognition simply from procedural learning. Similarly, AR may have led to self-reported improvements in QOL simply because patients expected their time and energy investment to pay off. We are currently enrolling a “passive” control group of experienced CI participants who are tested at baseline and after 8 weeks with no additional intervention. An alternative approach would be to include an “active” control group that receives clinician-guided intervention for a similar amount of time as the AR participants, but uses tasks that are unlikely to provide benefit.

Fifth, it remains unclear what AR approaches are most effective, what underlying changes are occurring in patients who do demonstrate benefits, and which patients would benefit most from comprehensive AR. We currently have no effective way to select appropriate candidates for AR other than the finding that participants with baseline poor word recognition seemed to demonstrate more gains from AR than those with better baseline word recognition. However, we conjecture that most adult patients could benefit from at least a short course of AR. We also do not know the appropriate duration (dosage) of therapy, or whether the required dosage varies from patient to patient. A major purpose of our ongoing study is to test the hypothesis that clinician-guided AR improves neurocognitive functions that underlie spoken language processing, and that these improvements mediate AR-related improvements in speech recognition. Thus far, in these 9 pilot participants, we have not found differences in neurocognitive functions for those who improved as a result of AR versus those who did not, but the sample size is small. Although studies have identified these neurocognitive functions as essential in recognizing degraded speech through a CI (26,27), it is unclear whether these functions can be improved through therapy and/or whether improvements in speech recognition will result. Also, it remains unclear whether more analytic versus synthetic approaches to training result in greater improvements, although there is some evidence that synthetic approaches may be more beneficial in older hearing-impaired individuals (28). From a much broader and contradictory viewpoint, it is possible that any type of AR primarily works by helping participants learn to use their CIs better, manage their listening environments more appropriately, and become more confident in communication scenarios. Although all of these are valuable goals for AR, they are much more difficult to demonstrate and quantify.

Sixth, patient attrition rates in clinician-guided AR studies are a problem. We are encouraged that 9 of our 12 initial enrollees completed 8 weeks of AR along with pre- and post-AR assessments. However, 3 enrollees dropped out of the study and did not complete all their AR sessions due to medical issues that arose (e.g., stroke, cancer diagnosis). Thus, planning of future studies needs to account for participant attrition, demonstrated here to be 25%. In addition, full participation in AR should account for compliance with daily home practice. Similarly, three of our participants (S1, S2, and S8) did undergo CI re-programming at some point between baseline testing and post-AR repeat testing, which may have impacted outcomes. However, these three participants were not the ones who demonstrated individual improvement in speech recognition or QOL, nor were they the ones driving the demonstrated changes in group mean speech recognition and QOL.

A concern raised by clinicians who are interested in implementing clinician-guided AR is its financial sustainability. Our program benefits from association with a teaching institution, permitting patients to enroll in AR for only a small enrollment fee, and insurance companies are not billed. In most clinical settings, a substantial barrier to adult AR implementation is the lack of reimbursement support for Audiologists, because social/medical insurance services all over the world most often define audiology services as “diagnostic tests” (29). Thus, audiologists and SLPs are encouraged to partner in order to provide quality patient care and boost overall reimbursement. If clinician-guided AR services are definitively determined to be efficacious through careful tracking of outcomes and dissemination of results, reimbursement for AR may be driven to improve.

Finally, although the role of the SLP as auditory-verbal therapist is common in pediatric CI programs, this is not the case in most adult CI programs. A contributor to this problem may be the paucity of SLPs who are comfortable offering adult AR services. Academic programs should strive to provide exposure to AR treatment during training to prepare more professionals to provide these services. Nonetheless, development of strong collaborations among surgeons, audiologists, and SLPs, along with demonstration of the efficacy of clinician-guided AR for adult CI users, may help shift the field to take a more comprehensive approach to rehabilitation and optimization of adult CI outcomes.

Conclusion

Clinician-guided AR represents a potentially efficacious approach to improving speech recognition and hearing-related QOL for adult CI users who have reached a performance plateau, particularly for those patients with relatively poor baseline performance. This approach deserves further development and exploration to optimize adult CI outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank David Pisoni, Luis Hernandez, and Susan Nittrouer for providing testing materials used in this study. We would also like to thank Bryan Ray for his assistance with statistical analyses.

Financial Disclosures: Pilot work with selected neurocognitive measures was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) Career Development Award 5K23DC015539–02 to Aaron C. Moberly.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors receive grant funding support from Cochlear Americas for a related investigator-initiated study of clinician-guided aural rehabilitation in newly implanted adult cochlear implant patients.

References

- 1.Firszt JB, Holden LK, Skinner MW, et al. Recognition of speech presented at soft to loud levels by adult cochlear implant recipients of three cochlear implant systems. Ear Hear 2004;25(4):375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gifford RH, Shallop JK, Peterson AM. Speech recognition materials and ceiling effects: considerations for cochlear implant programs. Audiol Neurotol 2008;13:193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hast A, Schlücker L, Digeser F, Liebscher T, Hoppe U. Speech perception of elderly cochlear implant users under different noise conditions. Otol Neurotol 2015;36(10):1638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holden LK, Finley CC, Firszt JB, et al. Factors affecting open-set word recognition in adults with cochlear implants. Ear Hear 2013;34(3):342–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenarz M, Sönmez H, Joseph G, Büchner A, Lenarz T. Long-term performance of cochlear implants in postlingually deafened adults. Otolaryng Head Neck 2012;147(1)112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rumeau C, Frère J, Montaut-Verient B, Lion A, Gauchard G, Parietti-Winkler C. Quality of life and audiologic performance through the ability to phone of cochlear implant users. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-L 2015;272(12):3685–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzog M, Schön F, Müller J, Knaus C, Scholtz L, Helms J. Long term results after cochlear implantation in elderly patients. Laryngo-rhino-otologie 2003;82(7):490–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris MS, Capretta NR, Henning SC, Feeney L, Pitt MA, Moberly AC. Postoperative rehabilitation strategies used by adults with cochlear implants: a pilot study. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 2016;1(3):42–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu QJ, Galvin III JJ. Auditory training for cochlear implant patients In Auditory Prostheses 2011. (pp. 257–278). Springer; New York. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M, Miller A, Campbell MM. Overview of nine computerized, home-based auditory-training programs for adult cochlear implant recipients. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2014. April 1;25(4):405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boothroyd A CASPER: Computer-assisted speech perception evaluation and training. InProceedings of the 10th annual conference of the rehabilitation society of North America 1987. (pp. 734–736). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sweetow RW, Sabes JH. The need for and development of an adaptive listening and communication enhancement (LACE™) program. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2006. September 1;17(8):538–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller JD, Watson CS, Kewley-Port D, Sillings R, Mills WB, Burleson DF. SPATS: Speech perception assessment and training system. In Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics 154ASA 2007 Nov 27 (Vol. 2, No. 1, p. 050005). ASA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henshaw H, Ferguson MA. Efficacy of individual computer-based auditory training for people with hearing loss: a systematic review of the evidence. PloS one. 2013. May 10;8(5):e62836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferguson M, Henshaw H. Computer and internet interventions to optimize listening and learning for people with hearing loss: accessibility, use, and adherence. American journal of audiology. 2015. September 1;24(3):338–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moberly AC, Bates C, Boyce L, Vasil K, Wucinich T, Baxter J, Ray C. Computerized rehabilitative training in older adult cochlear implant users: a feasibility study. Journal of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spahr AJ, Dorman MF, Litvak LM, Van Wie S, Gifford RH, Loizou PC, Loiselle LM, Oakes T, Cook S. Development and validation of the AzBio sentence lists. Ear and Hearing 2012;33(1):112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schafer EC, Pogue J, Milrany T. List equivalency of the AzBio sentence test in noise for listeners with normal-hearing sensitivity or cochlear implants. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2012;23(7):501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veneman CE, Gordon-Salant S, Matthews LJ, Dubno JR. Age and measurement time-of-day effects on speech recognition in noise. Ear and hearing. 2013. May;34(3):288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thornton AR, Raffin MJ. Speech-discrimination scores modeled as a binomial variable. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1978;21(3):507–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedley K, Lind C, Hunt P. Adult aural rehabilitation: A guide for CI professionals. Cochlear Limited; 2005.

- 22.Niquette P, Gudmundsen G, Killion M. QuickSIN Speech-in-Noise Test Version 1.3 Elk Grove Village, IL: Etymotic Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoddes E, Zarcone V, Smythe H, Phillips R, Dement WC. Quantification of sleepiness: a new approach. Psychophysiology 1973;10(4):431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capretta NR, Moberly AC. Does quality of life depend on speech recognition performance for adult cochlear implant users?. The Laryngoscope 2016;126(3):699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McRackan TR, Bauschard M, Hatch JL, Franko‐Tobin E, Droghini HR, Nguyen SA, Dubno JR. Meta‐analysis of quality‐of‐life improvement after cochlear implantation and associations with speech recognition abilities. The Laryngoscope 2017; July 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moberly AC, Houston DM, Castellanos I. Non‐auditory neurocognitive skills contribute to speech recognition in adults with cochlear implants. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. 2016;1(6):154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pisoni DB, Broadstock A, Wucinich T, Safdar N, Miller K, Hernandez LR, Vasil K, Boyce L, Davies A, Harris MS, Castellanos I. Verbal Learning and Memory After Cochlear Implantation in Postlingually Deaf Adults: Some New Findings with the CVLT-II. Ear and Hearing. 2017; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubinstein A, Boothroyd A. Effect of two approaches to auditory training on speech recognition by hearing-impaired adults. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1987;30(2):153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, Rev. 235 2017. July 11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. 2017. Medicare Fee Schedule for Speech-Language Pathologists, 2nd ed. 2016 December 16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.