Abstract

Prior research suggests that rural and minority communities participate in research at lower rates. While rural and minority populations are often cited as being underrepresented in research, population‐based studies on health research participation have not been conducted. This study used questions added to the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to understand factors associated with i) health research participation, ii) opportunities to participate in health research, and iii) willingness to participate in health research from a representative sample (n = 5,256) of adults in Arkansas. Among all respondents, 45.5% would be willing to participate in health research if provided the opportunity and 22.1% were undecided. Only 32.4% stated that they would not be willing to participate in health research. There was no significant difference in participation rates for rural or racial/ethnic minority communities. Furthermore, racial/ethnic minority respondents (Black or Hispanic) were more likely to express their willingness to participate.

Study Highlights

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

✓ Prior research and multiple commentaries suggest that rural and minority communities participate in health research at lower rates. However, recent studies have questioned this assumption. While rural and minority populations are often cited as being underrepresented in research, population‐based studies on health research participation have not been conducted.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

✓ This study used questions added to the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to understand factors associated with i) health research participation, ii) opportunities to participate in health research, and iii) willingness to participate in health research from a representative sample (n = 5,256) of adults in Arkansas.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

✓ Rural and racial/ethnic minority respondents reported similar rates of participation compared with their White and urban counterparts. Furthermore, racial/ethnic minority respondents (Black or Hispanic) were more likely to express willingness to participate in health research if provided the opportunity.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

✓ Translational researchers should focus on investigating and addressing barriers to research participation beyond the long‐held belief that rural and racial/ethnic minorities are less willing to participate.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the goal of health research is to create generalizable knowledge that improves human health.1 Since the launch of ClinicalTrials.gov in 2000, the number of studies registered at the NIH has grown exponentially, from 1,255 to more than 270,000.2 Although advances in health research have improved the length and quality of life, those benefits have not been shared by all; significant health disparities persist in many communities, with rural and minority communities bearing a disproportionate burden of disease and mortality.3 One factor that has been identified as contributing to health disparities is limited participation of rural and minority communities in research. In order to reduce health disparities, research must include “participants who represent the diversity of populations to which the study results will be applied” (p. 1062).4 Without the participation of diverse populations, knowledge generated by health research could have limited application. Therefore, it is imperative to understand factors related to diverse populations’ research participation, willingness to participate, and opportunities to participate as a first step to developing strategies to facilitate their participation in health research.

Prior research has shown that rural residents participate in research at lower rates than their urban counterparts.5 Key issues that may detrimentally affect rural residents’ participation in research include cultural sensitivity, geographic challenges (e.g., distance and isolation), misperceptions of research, and lack of opportunities to participate in research.6, 7, 8 Furthermore, prior research suggests that participation in health research is disproportionate across races and ethnicities. While racial/ethnic minorities constitute a third of the US population, most published studies show that they remain largely underrepresented in health research.9 For African Americans and Pacific Islanders, one consistent issue hampering research participation has been distrust and perceived discrimination, owing to a history of research abuse.9, 10, 11 Hispanic community members have also cited discrimination, stigma, fear of immigration authorities, and cultural norms as factors undermining research participation.12 A lack of cultural awareness from researchers and language barriers can also limit research opportunities by creating communication gaps between researchers and potential research participants.13, 14

While rural and minority populations are often cited as being underrepresented in research, population‐based studies on health research participation have not been conducted. Furthermore, we do not fully understand the factors associated with their willingness or unwillingness to participate in research. Prior studies on research participation have focused on one study or one population and have been conducted without inclusion of a representative sample of minorities and rural populations.15 This makes the extrapolation of findings to the general population particularly challenging.

The current study investigated associations between key factors (rural/urban, race/ethnicity, age, education, poverty level, employment status, marital status, access to health care, and health status) and i) health research participation, ii) opportunities to participate in health research, and iii) willingness to participate in health research from a representative sample of adults in Arkansas. Furthermore, the study investigated the independent effects of predictors (sociodemographic characteristics, access to health care, and presence of chronic conditions) on: i) health research participation, ii) opportunities to participate in health research, and iii) willingness to participate in health research. This will be the first study of its kind to examine factors related to participation, opportunity, and willingness to participate in health research from a large representative sample in a rural and diverse state.

METHODS

Data source

This study used the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) conducted in Arkansas as its data source. The BRFSS is a large, representative, state‐based telephone survey that involves a random digit‐dialing, multistage‐cluster sample survey designed to collect information on US noninstitutionalized civilian residents regarding their health‐related behaviors, chronic health conditions, and use of preventive services.16 In addition to the core component questions, states have the option to add questions that are asked of the respondents in their state. A fuller description of the BRFSS methodology and design can be found elsewhere.16 This study received an exemption from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB #205852).

Sample

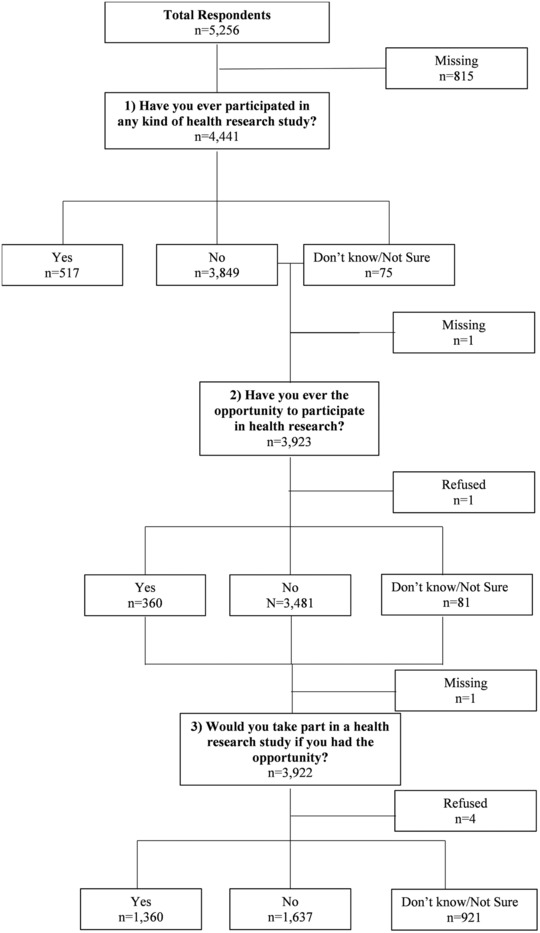

The analytical sample included 5,256 respondents aged18 years and older living in Arkansas who completed the 2015 BRFSS. Out of the 5,256 respondents who completed the BRFSS, 517 individuals answered “Yes” to the question “Have you ever participated in any kind of health research study?” 3,849 answered “No,” 75 answered “Don't know/Unsure,” and 815 were missing cases. Survey skip logic was structured so that the 517 people who responded “Yes” skipped the two questions related to opportunity to participate in health research and willingness to participate in health research if given the opportunity (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of past participation, past opportunity, and willingness to participate in health research. Data Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2015.16

Measures

Dependent variables

Three questions were added to the 2015 BRFSS in Arkansas pertaining to past participation in health research, past opportunity to participate in health research, and willingness to participate in health research if provided the opportunity. These variables were captured by the following questions: i) “Have you ever participated in any kind of health research study?”; ii) “Have you ever had the opportunity to participate in health research?”; and iii) “Would you take part in a health research study if you had the opportunity?” Answer options to these questions were “Yes,” “No,” “Don't Know/Not sure,” and “Refused.”

Independent variables

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, and federal poverty level (FPL) (Table 1). The percent of FPL income was computed using respondents’ self‐reported income and report of people living in the household in conjunction with the 2015 federal guidelines for poverty level. Rurality of respondents was captured by their residence status measured as a binary variable based on respondents’ zip code and categories from the Rural Urban Continuum Codes.17

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis

| Variables | Sample size (n) | Weighted % (population)a |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||

| Participated in Health Research | ||

| No | 3,849 | 90.6 |

| Yes | 517 | 9.4 |

| Opportunity to Participate in Health Research | ||

| No | 3,481 | 92.0 |

| Yes | 360 | 8.0 |

| Willingness to Participate in Health Research | ||

| No | 1,637 | 32.4 |

| Yes | 1,360 | 45.5 |

| Undecided | 921 | 22.1 |

| Independent Variables | ||

| Sociodemographic | ||

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 158 | 12.9 |

| 25–34 | 301 | 16.8 |

| 35–44 | 450 | 16.0 |

| 45–54 | 724 | 16.6 |

| 55–64 | 1,168 | 16.5 |

| 65+ | 2,455 | 21.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1,921 | 48.6 |

| Female | 3,335 | 51.4 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 4,086 | 76.0 |

| Black | 808 | 14.3 |

| Hispanic | 108 | 5.8 |

| Other | 254 | 4.0 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Living Together | 2,760 | 57.1 |

| Divorced/Separated | 915 | 16.1 |

| Widowed | 1,035 | 7.5 |

| Never Married | 546 | 19.3 |

| Education | ||

| Less than High School | 594 | 15.9 |

| High School Diploma/GED | 1,817 | 34.1 |

| Some College or higher | 2,845 | 50.0 |

| Poverty Level | ||

| <100% FPL | 599 | 20.9 |

| 100–199% FPL | 1,329 | 30.1 |

| 200–299% FPL | 673 | 16.2 |

| 300–399% FPL | 558 | 10.9 |

| ≥400% FPL | 968 | 21.9 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed/Self‐Employed | 1,877 | 51.3 |

| Not Employed | 601 | 18.1 |

| Retired | 2,014 | 18.7 |

| Unable to Work | 717 | 11.9 |

| Rurality/Urbanity | ||

| Metro/Urban | 2,789 | 57.6 |

| Nonmetro/Rural | 2,254 | 42.4 |

| Access to Care | ||

| Health Insurance | ||

| No | 319 | 12.3 |

| Yes | 4,911 | 87.7 |

| Usual source of care (has a personal doctor) | ||

| No | 519 | 16.5 |

| Yes | 4,713 | 83.5 |

| Unaffordability of health services (could not see doctor because of cost) | ||

| No | 4,695 | 84.5 |

| Yes | 536 | 15.5 |

| Health Check‐Up | ||

| Past Year | 4,041 | 68.8 |

| Past 2 Years | 476 | 11.9 |

| Past 5 Years | 235 | 7.6 |

| More Than 5 Years/ Never | 392 | 11.7 |

| Health Status | ||

| General Health | ||

| Excellent | 611 | 14.3 |

| Very Good | 1,429 | 28.0 |

| Good | 1,666 | 33.9 |

| Fair/Poor | 1,532 | 23.8 |

| Any Chronic Conditions | ||

| No | 1,051 | 32.4 |

| Yes | 4,205 | 67.6 |

Data Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2015.16

Weighted % are population estimates after sampling design (weights, strata, and stratification) has been accounted for so that the sample of respondents is representative of the population of civilian non‐institutionalized adults aged 18 years and older living in Arkansas. FPL = federal poverty level.

Respondents answered (“Yes”/”No”) regarding whether they had ever been told they had one or more of the following chronic health conditions: i) high blood pressure; ii) heart attack or myocardial infarction; iii) angina or coronary heart disease; iv) asthma; v) skin cancer; vi) other cancer; vii) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, or chronic bronchitis; viii) arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia; ix) depressive disorder, including depression, major depression, dysthymia, or minor depression; x) kidney disease; or xi) diabetes. A binary variable was created to capture if respondents had a chronic disease or not.

Perceived general health status was self‐rated by respondents who reported whether their general health was excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. The last two items were combined due to small numbers of responses in each category.

Four questions were used to define access to care18: i) “Do you have any kind of healthcare coverage, including health insurance, prepaid plans such as HMOs, government plans such as Medicare, or Indian Health Service?”; ii) “Do you have one person you think of as your personal doctor or healthcare provider?”; iii) “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost?”; and iv) “About how long has it been since you last visited a doctor for a routine checkup?”

Statistical analysis

SAS v. 9.419 (Cary, NC) was used to conduct statistical analyses. To describe the study population, weighted proportions for each dependent and independent variable were computed using PROC SURVEYFREQ to account for the complex sample design of the BRFSS. For unadjusted associations, each of the sociodemographic, rurality/urbanity, access to health care, perceived general health, and chronic conditions variables were cross‐tabulated with each of the three dependent variables. To account for the complex sampling design of the survey, the Rao‐Scott Chi‐Square test20 (χ2 R‐S)—a modified version of the chi‐square test—was used.

Multivariable regression models were fitted to confirm associations between the predictors (i.e., sociodemographic characteristics, rurality/urbanity, access to care, perceived general health, general health status, and chronic conditions) and the three outcomes of interest. PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC was used to accommodate the complex survey design in these analyses and estimate adjusted associations.

“Ever participated in health research” and “Opportunity to participate in health research” are dichotomous outcomes, thus a multivariable logistic regression was used. Willingness to participate in health research was measured on a nominal scale (“Yes”/”No”/”Undecided”), thus a multinomial logistic regression21 was conducted with the response “No” as the baseline category.

RESULTS

Weighted percentages are presented in Table 1. Most individuals (90.6%) had never participated in health research. Among those who had not participated, 92.0% had not had the opportunity to participate in health research. Almost half (45.5%) would be willing to participate in health research if given the opportunity; 32.4% stated they would not be willing to participate even if given the opportunity; and 22.1% were undecided.

Most respondents (76.0%) were non‐Hispanic White; 21.3% were 65 years or older; and 51.4% were females. More than half (57.1%) of respondents were married or in cohabitation. Fifty percent of respondents had some college or more, 51.3% were employed, 20.9% lived below the poverty line, and 42.4% lived in rural areas.

Most respondents had health insurance coverage (87.7%) and/or a usual source of care (83.5%), and 15.5% reported there was a time in the past year when they could not see a doctor due to cost. Most respondents (68.8%) had a health check‐up in the past year; however, for 11.7% it had been more than 5 years since their last check‐up.

Among respondents, 67.6% had at least one chronic condition. More specifically, 40.3% had hypertension; 29.7% had arthritis; 23.5% reported being depressed; 16.1% had asthma; 12.9% had diabetes; 9.8% had COPD; 6.6% reported skin cancer and 7.0% some other type of cancer; 5.6% had coronary heart disease; 5.4% sustained a heart attack; 3.8% experienced a stroke; and 3.2% had kidney disease.

Unadjusted associations

As shown in Table 2, no significant associations were found between respondents’ areas of residence (rural/urban) and past participation, past opportunity, or willingness to participate in health research. Likewise, we did not find any significant associations between respondents’ chronic condition status (“Yes”/”No”) and the three outcomes.

Table 2.

Unadjusted associations between past participation, past opportunity, and willingness to participate and sociodemographic characteristics, access to care, and health status

| Variables | Past Participation in Health Researcha | Opportunity to Participate in Health Researcha | Willingness to Participate in Health Researcha | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Undecided | ||||

| Sociodemographic | 90.6% | 9.4% | χ2 R‐S | 92.0% | 8.0% | χ2 R‐S | 32.2% | 45.5% | 22.1% | χ2 R‐S |

| Age Group | 6.94 | 10.20 | 73.64*** | |||||||

| 18–24 | 92.9 (87.8, 97.9) | 7.1 (2.1,12.2) | 91.9 (85.9,97.8) | 8.1 (2.2,14.1) | 17.3 (8.8,25.9) | 60.2 (49.2,71.2) | 22.4 (12.9,32.0) | |||

| 25–34 | 93.7 (89.9,97.5) | 6.3 (2.5,10.1) | 97.0 (94.8,99.3) | 3.0 (0.7,5.2) | 24.8 (17.8,31.7) | 56.4 (48.3,64.6) | 18.8 (12.6,25.0) | |||

| 35–44 | 91.5 (88.0, 95.1) | 8.5 (4.9,12.0) | 92.4 (88.8,96.0) | 7.6 (4.0,11.2) | 29.1 (22.7,35.6) | 51.6 (44.3,58.8) | 19.3 (13.8,24.8) | |||

| 45–54 | 90.0 (86.9,93.0) | 10.0 (7.0,13.1) | 91.4 (88.2,94.7) | 8.6 (5.3,11.8) | 30.6 (24.9,36.3) | 49.2 (42.8,55.7) | 20.1 (15.4,24.9) | |||

| 55–64 | 88.4 (85.4,91.4) | 11.6 (8.6,14.6) | 89.7 (86.3,93.0) | 10.3 (7.0,13.7) | 36.9 (32.0,41.8) | 38.8 (33.9,43.7) | 24.3 (19.928.6) | |||

| 65+ | 88.6 (86.5, 90.7) | 11.4 (9.3,13.5) | 90.3 (87.9, 92.6) | 9.7 (7.4,12.1) | 47.2 (43.6,50.7) | 26.2 (23.0,29.3) | 26.7 (23.4,30.0) | |||

| Sex | 1.66 | 0.25 | 1.50 | |||||||

| Male | 91.5 (89.4,93.6) | 8.5 (6.4,10.6) | 91.6 (89.5,93.8) | 8.4 (6.2,10.5) | 34.0 (30.1,37.8) | 44.5 (40.2,48.9) | 21.5 (18.1,24.9) | |||

| Female | 89.7 (88.0, 91.4) | 10.3 (8.6,12.0) | 92.3 (90.6, 94.1) | 7.7 (5.9,9.4) | 30.8 (27.9,33.8) | 46.4 (42.9,49.9) | 22.7 (19.9,25.6) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 1.73 | 5.51 | 22.53** | |||||||

| White | 90.2 (88.7,91.7) | 9.8 (8.3,11.3) | 92.4 (90.9,93.9) | 7.6 (6.1,9.1) | 35.0 (32.3,37.8) | 41.7 (38.7,44.7) | 23.3 (20.8,25.7) | |||

| Black | 92.7 (90.1,95.3) | 7.3 (4.7,9.9) | 88.5 (84.0,93.1) | 11.5 (6.9,16.0) | 21.7 (15.9,27.6) | 58.9 (51.2,66.6) | 19.3 (13.0,25.7) | |||

| Hispanic | 89.4 (80.2, 98.6) | 10.6 (1.4,19.8) | 95.4 (90.7,100.0) | 4.6 (0.0,9.3) | 24.6 (12.3,37.0) | 58.2 (44.0,72.4) | 17.2 (7.0,27.3) | |||

| Other | 92.8 (88.2,97.4) | 7.2 (2.6,11.8) | 91.7 (86.4,96.9) | 8.3 (3.1,13.6) | 32.4 (21.6,43.3) | 49.3 (37.3,61.4) | 18.2 (8.3,28.2) | |||

| Marital Status | 5.90 | 1.17 | 39.29*** | |||||||

| Married/Living Together | 89.4 (87.7,91.1) | 10.6 (8.9,12.3) | 91.7 (90.1,93.4) | 8.3 (6.6,9.9) | 35.4 (32.2,38.5) | 41.2 (37.7,44.7) | 23.4 (20.6,26.3) | |||

| Divorced/Separated | 93.5 (91.3,95.7) | 6.5 (4.3,8.7) | 91.2 (87.5,94.8) | 8.8 (5.2,12.5) | 25.8 (20.2,31.5) | 55.7 (49.1,62.4) | 18.4 (13.6,23.2) | |||

| Widowed | 92.8 (90.4,95.1) | 7.2 (4.9,9.6) | 91.9 (88.2,95.5) | 8.1 (4.5,11.8) | 45.2 (38.9,51.5) | 29.6 (23.3,35.8) | 25.2 (19.4,31.1) | |||

| Never Married | 90.7 (86.3,95.1) | 9.3 (4.9,13.7) | 93.6 (89.7,97.4) | 6.4 (2.6,10.3) | 23.7 (17.1,30.3) | 56.0 (48.1,63.9) | 20.2 (13.7,26.7) | |||

| Education | 34.59*** | 2.98 | 7.00 | |||||||

| Less than High School | 96.4 (94.2,98.7) | 3.6 (1.3,5.8) | 92.1 (87.7,96.5) | 7.9 (3.5,12.3) | 35.3 (27.9,42.7) | 46.8 (38.5,55.1) | 17.9 (11.9,23.8) | |||

| High School Diploma/GED | 93.7 (91.9,95.5) | 6.3 (4.5,8.1) | 93.7 (91.6,95.8) | 6.3 (4.2,8.4) | 34.7 (30.4,38.9) | 45.3 (40.5,50.0) | 20.1 (16.4,23.7) | |||

| Some College or Higher | 86.7 (84.5,88.9) | 13.3 (11.1,15.5) | 90.7 (88.8,92.6) | 9.3 (7.4,11.2) | 29.7 (26.6,32.8) | 45.2 (41.6,48.9) | 25.0 (21.9,28.1) | |||

| Poverty Level | 6.92 | 2.25 | 40.46*** | |||||||

| <100% FPL | 93.3 (90.4,96.3) | 6.7 (3.7,9.6) | 93.9 (90.5, 97.3) | 6.1 (2.7, 9.5) | 20.4 (15.2,25.6) | 62.9 (56.0,69.8) | 16.7 (11.1,22.4) | |||

| 100–199% FPL | 90.6 (87.6,93.5) | 9.4 (6.5,12.4) | 91.6 (88.6, 94.6) | 8.4 (5.4,11.4) | 32.2 (27.2,37.2) | 46.7 (41.0,52.4) | 21.1 (16.7,25.5) | |||

| 200–299% FPL | 92.0 (88.8,95.2) | 8.0 (4.8,11.2) | 92.6 (89.5,95.7) | 7.4 (4.3,10.5) | 33.0 (26.6,39.5) | 45.4 (37.9,52.8) | 21.6 (15.7,27.5) | |||

| 300–399% FPL | 88.3 (83.0,93.6) | 11.7 (6.4,17.0) | 90.2 (85.9, 94.6) | 9.8 (5.4,14.1) | 46.2 (37.9,54.5) | 32.5 (24.7,40.3) | 21.3 (15.3,27.3) | |||

| ≥400% FPL | 87.9 (85.0,90.8) | 12.1 (9.2,15.0) | 91.5 (88.7, 94.3) | 8.5 (5.7,11.3) | 30.8 (25.7,36.0) | 44.4 (38.3,50.4) | 24.8 (19.9,29.7) | |||

| Employment | 4.53 | 6.35 | 64.21*** | |||||||

| Employed/Self‐Employed | 90.9 (88.9,93.0) | 9.1 (7.0,11.1) | 92.1 (90.0,94.1) | 7.9 (5.9,10.0) | 30.9 (27.2,34.5) | 47.7 (43.5,51.8) | 21.5 (18.2,24.7) | |||

| Nonemployed | 92.7 (89.4,96.0) | 7.3 (4.0,10.6) | 95.1 (92.5,97.8) | 4.9 (2.2,7.5) | 23.4 (17.7,29.1) | 54.9 (47.4,62.3) | 21.7 (15.6,27.8) | |||

| Retired | 88.9 (86.6,91.2) | 11.1 (8.8,13.4) | 92.0 (90.0,94.1) | 8.0 (5.9,10.0) | 46.3 (42.5,50.2) | 25.7 (22.2,29.1) | 28.0 (24.4,31.6) | |||

| Unable to Work | 88.3 (84.6, 92.1) | 11.7 (7.9,15.4) | 88.9 (84.0,93.8) | 11.1 (6.2,16.0) | 30.2 (23.5,36.8) | 54.1 (46.7,61.5) | 15.7 (10.6,20.9) | |||

| Rurality/Urbanity | 1.15 | 1.44 | 3.45 | |||||||

| Metro/urban | 90.1 (88.2,91.9) | 9.9 (8.1,11.8) | 91.5 (89.6,93.4) | 8.5 (6.6,10.4) | 31.3 (28.0,34.7) | 44.7 (40.9,48.4) | 24.0 (20.9,27.1) | |||

| Nonmetro/rural | 91.5 (89.6,93.4) | 8.5 (6.6,10.4) | 93.2 (91.2,95.1) | 6.8 (4.9,8.8) | 32.4 (28.9,36.0) | 47.8 (43.6,51.9) | 19.8 (16.6,23.0) | |||

| Access to Care | ||||||||||

| Health Insurance | 0.10 | 0.69 | 8.58?? | |||||||

| No | 91.2 (86.4,96.0) | 8.8 (4.0,13.6) | 89.9 (84.3,95.6) | 10.1 (4.4,15.7) | 23.9 (16.3,31.6) | 58.2 (48.7,67.6) | 17.9 (10.9,24.9) | |||

| Yes | 90.4 (89.0, 91.8) | 9.6 (8.2,11.0) | 92.2 (90.8,93.6) | 7.8 (6.4,9.2) | 33.2 (30.7,35.7) | 44.0 (41.1,46.8) | 22.9 (20.5,25.2) | |||

| Usual Source of Care (has a personal doctor) | 3.29 | 0.81 | 4.34 | |||||||

| No | 93.8 (90.6, 97.0) | 6.2 (3.0,9.4) | 93.7 (90.0,97.3) | 6.3 (2.7,10.0) | 26.0 (19.2,32.7) | 52.6 (44.4,60.8) | 21.4 (14.8,28.0) | |||

| Yes | 90.0 (88.5,91.5) | 10.0 (8.5,11.5) | 91.7 (90.2,93.2) | 8.3 (6.8,9.8) | 33.4 (30.9,36.0) | 44.4 (41.5,47.3) | 22.2 (19.8,24.5) | |||

| Unaffordability of Health Services (could not see doctor because of cost) | 1.56 | 0.63 | 7.71?? | |||||||

| No | 90.2 (88.7,91.7) | 9.8 (8.3,11.3) | 91.8 (90.3,93.3) | 8.2 (6.7,9.7) | 33.9 (31.3,36.5) | 43.9 (40.9,46.8) | 22.2 (19.9,24.6) | |||

| Yes | 92.7 (89.5,95.8) | 7.3 (4.2,10.5) | 93.6 (89.8, 97.3) | 6.4 (2.7,10.2) | 24.3 (17.6,31.0) | 55.0 (47.3,62.8) | 20.7 (14.1,27.2) | |||

| Health Check‐Up | 5.76 | 1.92 | 5.70 | |||||||

| Past Year | 89.4 (87.7,91.1) | 10.6 (8.9,12.3) | 91.3 (89.7,93.0) | 8.7 (7.0,10.3) | 33.9 (31.0,36.7) | 44.3 (41.1,47.5) | 21.9 (19.4,24.4) | |||

| Past 2 Years | 91.5 (88.0,94.9) | 8.5 (5.1,12.0) | 93.6 (89.3,97.8) | 6.4 (2.2,10.7) | 29.8 (22.5,37.0) | 44.7 (36.5,53.0) | 25.5 (18.4,32.7) | |||

| Past 5 Years | 95.2 (91.5,99.0) | 4.8 (1.0,8.5) | 91.4 (85.0,97.8) | 8.6 (2.2,15.0) | 30.7 (20.3,41.2) | 52.6 (41.2,64.0) | 16.7 (8.6,24.7) | |||

| More Than 5 Years/Never | 92.6 (88.2,96.9) | 7.4 (3.1,11.8) | 94.3 (90.8,97.7) | 5.7 (2.3,9.2) | 26.8 (19.0,34.5) | 49.8 (40.4,59.2) | 23.4 (15.3,31.6) | |||

| Health Status | ||||||||||

| General Health | 6.58 | 4.44 | 4.42 | |||||||

| Excellent | 90.3 (86.8,93.8) | 9.7 (6.2,13.2) | 92.9 (89.5,96.3) | 7.1 (3.7,10.5) | 32.6 (25.6,39.5) | 44.8 (36.7,52.8) | 22.7 (15.9,29.5) | |||

| Very Good | 88.2 (85.1,91.3) | 11.8 (8.7,14.9) | 92.2 (89.6,94.9) | 7.8 (5.1,10.4) | 34.1 (29.6,38.7) | 41.3 (36.1,46.5) | 24.6 (20.2,28.9) | |||

| Good | 92.6 (90.6,94.6) | 7.4 (5.4,9.4) | 93.2 (91.2,95.2) | 6.8 (4.8,8.8) | 32.4 (26.1,35.0) | 47.4 (42.2,52.8) | 20.2 (17.5,26.5) | |||

| Fair/Poor | 90.4 (88.0, 92.9) | 9.6 (7.1,12.0) | 89.5 (86.1,92.9) | 10.5 (7.1,13.9) | 30.5 | 47.5 | 22.0 | |||

| Any Chronic Conditions | 3.63 | 20.0 | 3.09 | |||||||

| No | 92.7 (90.2,95.2) | 7.3 (4.8,9.8) | 92.5 (89.9,95.0) | 7.5 (5.0,10.1) | 28.9 (24.3,33.6) | 47.5 (42.0,53.0) | 23.6 (19.0,28.2) | |||

| Yes | 89.6 (88.0,91.2) | 10.4 (8.8,12.0) | 91.8 (90.1, 93.4) | 8.2 (6.6,9.9) | 34.0 (31.2,36.8) | 44.5 (41.4,47.7) | 21.4 (19.0,23.8) | |||

Data Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2015.16

Weighted percentages are population estimates after sampling design (weights, strata, and stratification) has been accounted for so that the sample of respondents is representative of the population of civilian non‐institutionalized adults aged 18 years and older living in Arkansas.

χ2 R‐S = Rao‐Scott Chi‐square test statistic.

FPL = federal poverty level.

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Only level of education was found to be associated with past participation in health research (χ2 R‐S (2) = 34.59, P < 0.001). Among respondents who had not completed high school/GED, 96.4% had not participated in health research, and 3.6% had participated. Of those who had at least some college education, 86.7% had not participated in health research, and 13.3% had participated.

Past opportunity to participate in health research was assessed among those respondents who had not yet participated in health research. There was not a statistically significant relationship between past opportunity to participate in health research and any of the selected independent variables.

Willingness to participate in health research was assessed among those respondents who had not yet participated in health research. Race/ethnicity was not found to be significantly associated with past participation and past opportunity to participate in health research; however, a significant association between race/ethnicity and willingness to participate in health research was seen (χ2 R‐S (6) = 22.53, P = 0.001). Among White respondents, 41.7% reported being willing to take part in health research if given the opportunity. Relative to White respondents, greater proportions of Black and Hispanic respondents who had never participated in research were willing to participate in health research (58.9% and 58.2%, respectively).

Significant associations were observed between willingness to participate in health research and poverty level (χ2 R‐S (8) = 40.46, P < 0.001). Among individuals living below the poverty line, 62.9% reported being willing to participate in research, 20.4% would not participate, and 16.7% were undecided. Among respondents living in more affluent households (≥400% FPL), 44.4% were willing to participate in health research, 30.8% would not participate, and 24.8% were undecided.

Employment status was significantly associated (χ2 R‐S (6) = 64.21, P < 0.001) with willingness to participate in health research. Among the employed, 47.7% stated they would be willing to participate, 30.9% would not participate, and 21.5% were undecided. More than half (54.9%) of unemployed respondents reported willingness to participate, 23.4% would not participate, and 21.7% were undecided. Of those unable to work, 54.1% reported willingness to participate, 30.1% would not participate even if given the opportunity, and 15.7% were undecided.

The inability to afford health services and willingness to participate in health research were significantly associated (χ2 R‐S (2) = 7.71, P = 0.02). Those who reported a time in the year when they needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost (55.0%), were more likely to be willing to participate in health research.

Adjusted associations

Regression analyses were conducted to examine whether the unadjusted significant associations continued after adjustment of covariates in the models. Table 3 shows the results of multivariable logistic regression models for “ever participated in health research” and “opportunity to participate in health research.” As found in unadjusted associations, neither rural residence nor chronic condition status were associated with past participation or past opportunity to participate in health research.

Table 3.

Adjusted associations between past participation, past opportunity, and sociodemographic characteristics, access to care, and health status

| Multivariable logistic regression: odds ratios and 95% confidence intervalsa | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Past participation in health research (yes vs. no) | Past opportunity in health research (yes vs. no) |

| Sociodemographic | ||

| Age Group | ||

| 18–24 | 0.60 (0.22,1.63) | 0.70 (0.22,2.21) |

| 25–34 | 0.45 (0.20,1.01) | 0.18** (0.07,0.50) |

| 35–44 | 0.59 (0.32,1.07) | 0.46* (0.23,0.95) |

| 45–54 | 0.75 (0.46,1.22) | 0.59 (0.32,1.08) |

| 55–64 | 0.83 (0.56,1.22) | 0.75 (0.44,1.29) |

| 65+ | — | — |

| Sex | ||

| Male | — | — |

| Female | 1.26 (0.88,1.79) | 0.91 (0.61,1.36) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | — | — |

| Black | 0.89 (0.53,1.52) | 2.02* (1.16,3.52) |

| Hispanic | 1.46 (0.50,4.30) | 0.59 (0.17,1.2.07) |

| Other | 0.88 (0.40,1.97) | 1.29 (0.57,2.95) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Living Together | — | — |

| Divorced/Separated | 0.59* (0.38,0.93) | 1.01 (0.60,1.72) |

| Widowed | 0.55** (0.34,0.90) | 0.75 (0.42,1.37) |

| Never Married | 1.20 (0.61,2.38) | 0.72 (0.33,1.55) |

| Education | ||

| Less than High School | 0.21*** (0.10,0.47) | 0.62 (0.31,1.24) |

| High School Diploma/GED | 0.41*** (0.27,0.63) | 0.55* (0.34,0.89) |

| Some College or higher | — | — |

| Employment | ||

| Employed/Self‐Employed | — | — |

| Nonemployed | 0.92 (0.50,1.68) | 0.61 (0.28,1.34) |

| Retired | 0.93 (0.62,1.40) | 0.60 (0.35,1.02) |

| Unable to Work | 1.98** (1.21,3.23) | 1.09 (0.51,2.36) |

| Poverty Level | ||

| <100% FPL | — | — |

| 100–199% FPL | 1.28 (0.70,2.34) | 1.08 (0.53,2.21) |

| 200–299% FPL | 0.91 (0.42,1.95) | 1.02 (0.46,2.28) |

| 300–399% FPL | 1.09 (0.51,2.31) | 1.27 (0.50,3.21) |

| ≥400% + FPL | 1.15 (0.57,2.33) | 1.15 (0.46,2.90) |

| Rurality/Urbanity | ||

| Nonmetro/rural | — | — |

| Metro/urban | 1.06 (0.75,1.49) | 1.22 (0.78,1.92) |

| Access to Care | ||

| Health Insurance | ||

| No | — | — |

| Yes | 0.54 (0.27,1.07) | 0.37** (0.17,0.82) |

| Usual Source of Care (has a personal doctor) | ||

| No | — | — |

| Yes | 1.32 (0.71,2.46) | 1.17 (0.58,2.33) |

| Unaffordability of Health Services (could not see doctor because of cost) | ||

| No | — | — |

| Yes | 0.85 (0.48,1.50) | 0.72 (0.34,1.49) |

| Health Check‐Up | ||

| Past Year | — | — |

| Past 2 Years | 0.88 (0.51,1.51) | 0.91 (0.44,1.85) |

| Past 5 Years | 0.54 (0.22,1.37) | 1.18 (0.46,3.04) |

| More Than 5 Years/Never | 0.76 (0.39,1.47) | 0.65 (0.29,1.45) |

| Health Status | ||

| General Health | ||

| Excellent | 1.29 (0.72,2.31) | 0.55 (0.27,1.12) |

| Very Good | 1.29 (0.81,2.07) | 0.72 (0.41,1.25) |

| Good | 0.88 (0.56,1.38) | 0.63 (0.36,1.13) |

| Fair/Poor | — | — |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| No | — | — |

| Yes | 1.38 (0.85,2.24) | 0.82 (0.49,1.37) |

Data Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2015.16

“—” Denotes reference category.

Odds ratios are population estimates of selected predictors after sampling design (weights, strata, and stratification) has been accounted for, and are based on imputation with M = 20 imputed data sets.

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01;*** P < 0.001.

In adjusted models, significant associations between level of education and past participation held. Compared with respondents with at least some college education, those whose highest level of education was a high school diploma/GED and those with less than a high school education were less likely to have participated in health research (odds ratio (OR) = 0.41; 95% confidence intervals (CI) = 0.27–0.63; and OR = 0.21; CI = 0.10–0.47, respectively).

Compared with respondents who were married/living together, those who were divorced/separated or widowed were less likely to have participated in health research (OR = 0.59; CI = 0.38–0.93; and OR = 0.55; CI = 0.34–0.90, respectively). Relative to employed respondents, respondents who were unable to work were almost twice as likely to have participated in research (OR = 1.98; CI = 1.21–3.23).

With respect to opportunity to participate in health research, we found that respondents aged 25–34 and 35–44 were less likely to have had an opportunity relative to respondents aged 65 years or older (OR = 0.18; CI = 0.08–0.50; and OR = 0.46; CI = 0.23–0.95, respectively).

Compared with White respondents, Blacks were twice as likely to have had the opportunity to participate (OR = 2.02; CI = 1.16–3.52). Compared with respondents with at least some college education, those whose highest level of education was a high school diploma/GED were less likely to have had the opportunity to participate (OR = 0.55; CI = 0.34–0.89). Relative to respondents without health insurance coverage, respondents with health insurance coverage were less likely to have had the opportunity to participate (OR = 0.37; CI = 0.17–0.82).

Table 4 shows the results of the multinomial logistic regression model for willingness to participate in health research. When compared with respondents 65 or older, all age groups (15–64 years) were more likely to respond “Yes” than “No” when asked if they would participate in health research. Compared with White respondents, non‐Hispanic Blacks were more likely to respond “Yes” than “No” (OR = 1.74; CI = 1.14–2.67). Compared with married/living together respondents, divorced/separated respondents were more likely to respond “Yes” than “No” (OR = 1.62; CI = 1.10–2.38). Compared with respondents with at least some college education, those who had not completed a high school diploma/GED were less likely to respond either “Yes” or “Undecided” than “No” (OR = 0.51; CI = 0.33–0.80; OR = 0.51; CI = 0.30–0.86). Similarly, relative to respondents with at least some college education, those who had not completed a high school degree/GED and those with a high school diploma/GED were less likely to respond either “Yes” or “Undecided” than “No.”

Table 4.

Adjusted associations between willingness to participate in health research and sociodemographic characteristics, access to care, and health status

| Multinomial logistic regression: odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals a | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Willingness to participate in health research | |

| Sociodemographic | (yes vs. no) | (undecided vs. no) |

| Age Group | ||

| 18–24 | 5.68*** (2.63,12.25) | 2.20 (0.84,5.76) |

| 25–34 | 2.97*** (1.67,5.27) | 1.07 (0.52,2.23) |

| 35–44 | 2.48** (1.49,4.12) | 1.07 (0.59,1.93) |

| 45–54 | 2.15** (1.38,3.35) | 1.18 (0.70,1.97) |

| 55–64 | 1.58** (1.10,2.27) | 1.17 (0.79,1.56) |

| 65+ | — | — |

| Sex | ||

| Male | — | — |

| Female | 1.16 (0.87,1.51) | 1.13 (0.84,1.50) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | — | — |

| Black | 1.74* (1.14,2.67) | 1.39 (0.4,2.30) |

| Hispanic | 2.06 (0.89,4.77) | 1.43 (0.52,3.89) |

| Other | 1.08 (0.59,1.96) | 0.82 (0.37,1.84) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Living Together | — | — |

| Divorced/Separated | 1.62* (1.10,2.38) | 1.05 (0.67,1.67) |

| Widowed | 1.00 (0.66,1.54) | 0.92 (0.61,1.38) |

| Never Married | 1.12 (0.68,1.86) | 0.98 (0.54,1.79) |

| Education | ||

| Less Than High School | 0.51* (0.33,0.80) | 0.51* (0.30,0.86) |

| High School Diploma/GED | 0.58** (0.43,0.87) | 0.60** (0.42,0.87) |

| Some College or higher | — | — |

| Employment | ||

| Employed/Self‐Employed | — | — |

| Nonemployed | 1.32 (0.85,2.06) | 1.19 (0.70,2.01) |

| Retired | 0.91 (0.60,1.38) | 1.13 (0.75,1.70) |

| Unable to Work | 1.19 (0.71,2.01) | 0.78 (0.41,1.46) |

| Poverty level | ||

| <100% FPL | — | — |

| 100–199% FPL | 0.69 (0.44,1.08) | 0.74 (0.44,1.25) |

| 200–299% FPL | 0.72 (0.43,1.19) | 0.75 (0.41,1.35) |

| 300–399% FPL | 0.48* (0.26,0.88) | 0.57 (0.30,1.09) |

| ≥400% FPL | 0.68 (0.39,1.20) | 0.83 (0.46,1.50) |

| Rurality/Urbanity | ||

| Nonmetro/rural | — | — |

| Metro/urban | 0.90 (0.69,1.17) | 1.17 (0.84,1.62) |

| Access to Care | ||

| Health Insurance | ||

| No | — | — |

| Yes | 0.85 (0.49,1.46) | 1.07 (0.55,2.07) |

| Usual Source of Care (has a personal doctor) | ||

| No | — | — |

| Yes | 1.10 (0.67,1.82) | 0.87 (0.49,1.53) |

| Unaffordability of Health Services (could not see doctor because of cost) | ||

| No | — | — |

| Yes | 1.25 (0.79,2.00) | 1.21 (0.71,2.07) |

| Health Check‐Up | ||

| Past Year | — | — |

| Past 2 Years | 0.93 (0.61,1.41) | 1.21 (0.76,1.92) |

| Past 5 Years | 1.06 (0.57,1.96) | 0.79 (0.37,1.71) |

| More Than 5 Years | 1.20 (0.71,2.03) | 1.32 (0.78,2.25) |

| Health Status | ||

| General Health | ||

| Excellent | 0.76 (0.44,1.30) | 0.69 (0.39,1.23) |

| Very Good | 0.83 (0.55,1.27) | 0.82 (0.51,1.33) |

| Good | 0.90 (0.62,1.32) | 0.80 (0.52,1.22) |

| Fair/Poor | — | — |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| No | — | — |

| Yes | 1.19 (0.81,1.75) | 0.95 (0.64,1.41) |

Data Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2015.(16)

“—” Denotes reference category.

Odds ratios are population estimates of selected predictors after sampling design (weights, strata, and stratification) has been accounted for, and are based on imputation with M = 20 imputed data sets.

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

This article used three questions added to the Arkansas BRFSS to examine the relationship between key demographic and health status factors and health research participation, opportunities to participate in health research, and willingness to participate in health research. This is the first study to examine factors related to research participation, opportunity, and willingness in a large representative sample in a relatively rural and diverse state. Therefore, it makes a significant contribution to the current literature on research participation.

While only 8.5% of rural respondents had participated in health research, there was not a significant difference in participation rates, willingness to participate, or opportunity to participate for rural/urban. This is not consistent with prior literature that shows rural populations have lower opportunity and participation rates.5, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 This unexpected finding could be influenced by the extensive community‐based participatory research capacity that the states only academic medical center (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) had invested in to better engage rural and minority participants.

One of the most encouraging findings is that among all respondents, 45.5% would be willing to participate if provided the opportunity and another 22.1% were undecided. Only 32.4% stated that they would not be willing to participate in health research. In fact, racial/ethnic minority participants (Black or Hispanic) were more likely to express their willingness to participate in health research if provided the opportunity than White respondents. There is no difference in participation rates between racial/ethnic minorities, yet among those who have not participated, racial/ethnic minorities report both more opportunity and more willingness. These findings are inconsistent with several nonpopulation‐based studies that suggest racial/ethnic minorities are less willing to participate.9, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 However, the findings are consistent with a small number of more recent studies that document a willingness to participate among racial and ethnic minorities.37, 38, 39 This study adds to the growing body of literature suggesting barriers beyond willingness.37, 38, 39 Specifically, the paradoxical findings of this study, which showed no difference in the participation rates of racial/ethnic minorities, yet also showed racial/ethnic minorities report both more opportunity and more willingness, needs further exploration.

Furthermore, there was no significant difference in participation rates, willingness to participate, or opportunity to participate among those with and without a chronic condition. This was somewhat surprising, as prior research has shown that those with chronic conditions are more likely to participate.6, 40, 41, 42 Another unexpected finding was that those who have insurance were less likely to have had the opportunity to participate, and those who were uninsured reported greater opportunity. Furthermore, those who reported not being able to afford to go to the doctor, and those without a job reported greater willingness to participate. These findings are in contrast to other studies that have suggested persons with limited access to healthcare services and persons who are uninsured are less likely to participate in research.24, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 These unexpected findings may be due to the high proportion of uninsured patients who are treated by the academic medical center, which is also the primary health research organization in the state.

Younger participants (<65 years) reported having participated in research at lower rates and also reported less opportunity to participate in research. However, they expressed a greater willingness to participate. This could be due to the length of their opportunity (i.e., those who are 65 or older have lived longer, and therefore have more years of opportunity). While the finding is not surprising, the increased willingness of younger age groups is encouraging. Consistent with prior literature, as education increased, so did rates of participation, opportunity, and willingness. Not surprisingly, those who had a previous opportunity to participate in health research, but had chosen not to participate, were less likely to be willing to participate in health research.

Strengths and limitations

This study is strengthened by the large representative sample of respondents in Arkansas who took part in the 2015 BRFSS. However, the study does have limitations. The study relied on self‐reported responses and, therefore, is subject to response bias. Although the BRFSS data collection does include both land‐line and cell phone interviews, it does not include those without access to a phone. However, weighting the survey data to be representative of the state's population should compensate for any potential selection biases in sampling. The majority of the weighted sample—like the majority of Arkansas residents—were Caucasian, insured, and living above poverty levels. Therefore, important insights may be gained via oversampling of rural, minority, and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups in future population‐based surveys. Additionally, those who are participating in the BRFSS may be more likely to report willingness to participate in health research than those who refused the BRFSS interview. Despite these limitations, this is the largest study of its kind using a representative sample. The study adds key insights into the factors associated with research participation, opportunity, and willingness to participate.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests for this work.

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed by the authors contributing to this article do not reflect the opinions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention which is responsible for the quality of the BRFSS Data. The authors thank the Arkansas Department of Health for collecting the BRFSS data with the added research participation questions, housing the collected data, and granting the authors access to the data for analysis.

Funding

This project was supported by a Translational Research Institute, grant (#1U54TR001629‐01A1) through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Contributions

P.A.M., C.R.L., B.R., R.S.P., L.J., A.H., H.C.F., and M.R.N. wrote the article; P.A.M., C.R.L., J.P.S., H.C.F., and M.R.N. designed the research; M.R.N., C.R.L., J.P.S., B.R., and H.C.F. analyzed the data.

References

- 1. Zarin, D.A. , Tse, T. , Williams, R.J. & Carr, S . Trial reporting in ClinicalTrials.gov — The final rule. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 1998–2004, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institutes of Health , US National Library of Medicine. Trends, Charts, and Maps. Clinicaltrials.gov: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/resources/trends.

- 3. US Department of Health and Human Services , Office of the Secretary, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, and Office of Minority Health. HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities Implementation Progress Report. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Killien, M. et al Involving minority and underrepresented women in clinical trials: the National Centers of Excellence in Women's Health. J. Womens Health Gend. Based Med. 9, 1061–1070, (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanner, A. , Kim, S.H. , Friedman, D.B. , Foster, C. & Bergeron, C.D . Barriers to medical research participation as perceived by clinical trial investigators: communicating with rural and African American communities. J. Health Commun. 20, 88–96, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morgan, L.L. , Fahs, P.S. & Klesh, J . Barriers to research participation identified by rural people. J. Agric. Saf. Health 11, 407–414, (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pribulick, M. , Willams, I.C. & Fahs, P.S . Strategies to reduce barriers to recruitment and participation. Online J. Rural Nurs. Health Care 10, 22–33, (2010). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Friedman, D.B. , Foster, C. , Bergeron, C.D. , Tanner, A. & Kim, S.H . A qualitative study of recruitment barriers, motivators, and community‐based strategies for increasing clinical trials participation among rural and urban populations. Am. J. Health Promot. 29, 332–338, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. George, S. , Duran, N. & Norris, K . A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am. J. Public Health 104, E16–E31, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brewer, L.C. et al African American women's perceptions and attitudes regarding participation in medical research: the Mayo Clinic/The Links, Incorporated partnership. J. Womens Health 23, 681–687, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Katigbak, C. , Foley, M. , Robert, L. & Hutchinson, M.K . Experiences and lessons learned in using community‐based participatory research to recruit Asian American Immigrant Research Participants. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 48, 210–218, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shedlin, M.G. , Decena, C.U. , Mangadu, T. & Martinez, A . Research participant recruitment in Hispanic communities: lessons learned. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 13, 352–360, (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang, H.H. & Coker, A.D . Examining issues affecting African American participation in research studies. J. Black Stud. 40, 619–36, (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park, H. , Sha, M.M. & Olmsted, M . Research participant selection in non‐English language questionnaire pretesting: findings from Chinese and Korean cognitive interviews. Qual. Quant. 50, 1385–1398, (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Trauth, J.M. , Musa, D. , Siminoff, L. , Jewell, I.K. & Ricci, E . Public attitudes regarding willingness to participate in medical research studies. J. Health Soc. Policy 12, 23–43, (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. US Department of Agriculture , Economic Research Service. Rural‐Urban Continuum Codes Documentation; 2013. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation/.

- 18. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . Healthy People 2020: Access to Health Services; 2016. Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Access-to-Health-Services.

- 19. SAS/STAT . SAS Institute: Cary, NC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rao, J.N.K. & Scott, A.J . On chi‐square tests for multiway contingency tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. Ann. Stat. 12, 46–60, (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Agresti, A . An introduction to categorical data analysis. 2nd ed New York: Wiley‐Interscience; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paul, C.L. et al Diabetes in rural towns: effectiveness of continuing education and feedback for healthcare providers in altering diabetes outcomes at a population level: protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Implement. Sci. 8, 30, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Befort, C.A. , Bennett, L. , Christifano, D. , Klemp, J.R. & Krebill, H . Effective recruitment of rural breast cancer survivors into a lifestyle intervention. Psychooncology 24, 487–490, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baquet, C.R. , Commiskey, P. , Mullins, C.D. & Mishra, S.I . Recruitment and participation in clinical trials: socio‐demographic, rural/urban, and health care access predictors. Cancer Detect. Prev. 30, 24–33, (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bass, B. , Pross, D. & Bell, P . Recruitment for breast screening in a rural practice. Trial of a physician's letter of invitation. Can. Fam. Physician 40, 1730–1739, 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Engelman, K.K. et al. Impact of geographic barriers on the utilization of mammograms by older rural women. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 50, 62–68, (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tanner, A. , Kim, S. , Friedman, D. , Foster, C. & Bergeron, C . Barriers to medical research participation as perceived by clinical trial investigators: communicating with rural and African American communities. J. Health Commun. 20, 88–96, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hussian‐Gambles, M. Ethnic minority under‐representation in clinical trials: Whose responsibility is it anyway? J. Health Organ. Manag. 17, 138–143, (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levkoff, S. & Sanchez, H . Lessons learned about minority recruitment and retention from the Centers on Minority Aging and Health Promotion. Gerontologist 43, 18–26, (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moreno‐John, G. et al Ethnic minority older adults participating in clinical research: developing trust. J. Aging Health 16, 93S–123S, (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shavers, V.L. , Lynch, C.F. & Burmeister, L.F . Factors that influence African‐Americans' willingness to participate in medical research studies. Cancer 91, 233–236, (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Green, B.L. et al. African‐American attitudes regarding cancer clinical trials and research studies: results from focus group methodology. Ethn. Dis. 10, 76–86, (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dennis, B. & Neese, J . Recruitment and retention of African‐American elders into community‐based research: Lessons learned. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 14, 3–11, (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Williams, C.L. , Tappen, R. , Buscemi, C. , Rivera, R. & Lezcano, J . Obtaining family consent for participation in Alzheimer's research in a Cuban‐American population: strategies to overcome the barriers. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 16, 183–187, (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shavers, V.L. , Lynch, C.F. & Burmeister, L.F . Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Ann. Epidemiol. 12, 248–256, (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Murthy, V.H. , Krumholz, H.M. & Gross, C.P . Participation in cancer clinical trials: race‐, sex‐, and age‐based disparities. JAMA 291, 2720–2726, (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McElfish, P.A. et al Leveraging community‐based participatory research capacity to recruit Pacific Islanders into a genetics study. J. Commun. Genet. 8, 283–291, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jones, B.L. , Vyhlidal, C.A. , Bradley‐Ewing, A. , Sherman, A. & Goggin, K . If we would only ask: how Henrietta Lacks continues to teach us about perceptions of research and genetic research among African Americans today. J. Racial Ethn. Health Dispar. 4, 735–45, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wendler, D. et al Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 3, e19, (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mc Grath‐Lone, L. , Day, S. , Schoenborn, C. & Ward, H . Exploring research participation among cancer patients: analysis of a national survey and an in‐depth interview study. BMC Cancer 15, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shannon‐Dorcy, K. & Drevdahl, D.J . “I had already made up my mind”: patients and caregivers' perspectives on making the decision to participate in research at a US cancer referral center. Cancer Nurs. 34, 428–433, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Higashi, R.T. et al. Multiple comorbidities and interest in research participation among clients of a nonprofit food distribution site. Clin. Transl. Sci. 8, 584–590, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sateren, W.B. et al How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 20, 2109–17, (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Giuliano, A.R. et al Participation of minorities in cancer research: the influence of structural, cultural, and linguistic factors. Ann. Epidemiol. 10, S22–S34, (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mandelblatt, J.S. , Yabroff, K.R. & Kerner, J.F . Equitable access to cancer services: a review of barriers to quality care. Cancer 86, 2378–2390, (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Harris, Y. , Gorelick, P. , Samuels, P. & Bempong, I . Why African Americans may not be participating in clinical trials. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 88, 630–4, (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brown, D.R. , Fouad, M.N. , Basen‐Engquist, K. & Tortolero‐Luna, G . Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Ann. Epidemiol. 10, S13–S21, (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]