Abstract

The Assay Guidance Manual (AGM) is an eBook of best practices for the design, development, and implementation of robust assays for early drug discovery. Initiated by pharmaceutical company scientists, the manual provides guidance for designing a “testing funnel” of assays to identify genuine hits using high‐throughput screening (HTS) and advancing them through preclinical development. Combined with a workshop/tutorial component, the overall goal of the AGM is to provide a valuable resource for training translational scientists.

MEASUREMENT TECHNOLOGIES IN TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCES: QUANTITATIVE BIOLOGY AND PHARMACOLOGY

Advances in basic research among academia and small biotech startups have led to proposals of innovative therapeutic approaches to help address unmet medical needs. However, a large gap exists between the basic research conducted in such organizations and the translation of those fundamental advances into therapeutics that historically has remained the expertise of large pharmaceutical companies. This situation is changing with the development of collaboration models involving government, academia, industry, and disease philanthropy. Moreover, there is an evolving paradigm for drug discovery and early development within the academic sector as universities are increasingly focusing on commercializing research. While translational scientists were historically trained within the pharmaceutical industry, the newer public‐private collaborative models of drug discovery necessitate training opportunities for scientists working in the public sector.

The reasons for clinical failures are manifold and complex, and factors include: choices made at the discovery phase of lead identification and optimization, poor understanding of disease pathogenesis, poor pharmacokinetics (PKs)/pharmacodynamics, nonpredictive animal models, poor trial design, wrong patient population genetics and demographics, toxicity associated with modulation of the target, wrong outcome measures, as well as changing business and financial priorities.1 Recent publications have highlighted the need to train health professionals to appreciate the complexities throughout the translational continuum so that they can address deficiencies in the process and improve the likelihood of clinical success.2, 3 The concept of quantitative biology and pharmacology was developed early in many pharmaceutical research laboratories with a goal of successfully translating basic biology into viable drug discovery projects. The practice of quantitative biology and pharmacology requires a multidisciplinary approach spanning basic cell biology, biochemistry, chemistry, physics, pharmacology, engineering, statistics, automation, and information technology, while encompassing concepts in the subdisciplines of bioanalytical chemistry and bioanalysis. This practice is particularly important in developing biologically, physiologically, and pharmacologically relevant assays. Similarly, there have been multidisciplinary approaches to developments in novel signal generation and detection technologies, cellular biology methodologies, liquid handling, miniaturization, data analysis, and engineering systems solutions. Advances in these technologies and their adoption into the practice of quantitative biology and pharmacology have necessitated a different medium than traditional books and compendia for training translational scientists.

The Assay Guidance Manual (AGM) was developed to provide researchers with best‐practice guidelines and quantitative biology and pharmacology concepts for robust assay development, and was utilized to train therapeutic area scientists in its original version at Eli Lilly & Company and Sphinx Pharmaceuticals. The AGM has been a free and publicly available resource since 2005, currently accessible as an eBook on the National Library of Medicine (NLM), National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Bookshelf (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53196).4 In its current form as a dynamic, readily updatable eBook with continued renewal and expansion of content, the AGM is widely accessed (>30,000 views/month in 2017) by scientists from pharma, biotech, government, and academic research laboratories. Although assay development is a basic skill that is addressed throughout the biomedical curricula, advances in assay technologies, instrumentation, and analytical technologies, in addition to data acquisition and analysis software for large data sets, require constant adoption and training in research laboratories. Therefore, one‐time training during undergraduate or graduate education is inadequate in the long run. In this tutorial, we describe how the AGM contributes to the training and education of translational scientists. Chapters of the AGM provide guidelines on a wide range of topics spanning preclinical development and usage of the different chapters indicates areas of interest among drug discovery scientists. This information has contributed to the development of assay guidance workshops that are based on critical concepts from the AGM. Ten workshops have been conducted throughout the United States since 2015 and both the attendance and demand have remained high. Our vision is for the AGM to serve as a reliable and comprehensive resource maintained by the drug discovery community for training translational scientists worldwide.

BIOLOGICAL, PHYSIOLOGICAL, AND PHARMACOLOGICAL RELEVANCE

The AGM addresses the “nuts and bolts” of designing and validating biologically and physiologically relevant assays used throughout the preclinical discovery phase. Validity, reproducibility, and stability of these measurements are critical in high‐throughput screening (HTS), hit validation, lead optimization, and regulatory enabling studies to advance discovery projects effectively. This level of reliability is important because HTS involves testing large libraries of molecules with considerable investment in resources, such as reagents, compound management, automation, acquisition, data storage, and the analysis of millions of data points. Ultimately, the quality and reliability of this discovery process determines whether drug leads and candidates are identified and confirmed, and the choices made at this stage set the course of drug development. The AGM aims to reduce the amount of “garbage‐in, garbage‐out” by helping researchers develop assays that have biological relevance and superior performance metrics.

It is important to clearly define what significance and relevance mean in assay design and implementation. The term significance should be used in the context of statistical hypothesis testing. Statistical significance is a measure of how likely an observed result could have occurred on the basis of a set of assumptions.5 For instance, an event that is statistically significant is unlikely to have occurred by chance alone. Biological relevance of an event in any system (i.e., biochemical, cellular, tissue, and organism) is defined as being considered by expert judgment as important or meaningful.6 It is critical to consider the size and duration of the event that would be considered biologically relevant at the design stage of the assay before the process of decision making begins. The assay then needs to be optimized to measure the predefined biologically relevant event with sufficient statistical power to allow detection of the event if it occurs. The biological event generally will only be physiologically relevant if the genetic and biochemical behavior is modified, resulting in an observable and measurable phenotypic outcome related to the living system. Here, one could cite how carcinogens and other toxicants induce cell proliferation, tumor development, or result in cytotoxicity. Physiological relevance implies that appropriate biological systems (e.g., cells, tissues, and animal models) are used in the testing process and the magnitude of measured effects is in a physiological range to draw valid conclusions about the disease pathology. Pharmacological relevance implies that an agent at the appropriate dose and exposure can affect the biology to favorably alter phenotype and patient outcomes associated with the disease hypothesis. In all these cases, the biological, physiological, and pharmacological effects should be reproducible and measured quantitatively with statistical significance to ensure reliable decision making. Hence, the analytical measurement procedures need to be carefully designed to optimize assays that can be affected by reagents, instrumentation, interference and artifacts, automation, test compounds, controls, and data analysis models. This integrated approach to the development of assays that support preclinical discovery was recognized as a critical skill when HTS, hit validation, and lead optimization practices were developing in the early 1990s.

HISTORY OF THE AGM AND THE NCBI/NLM EBOOK

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the advent of combinatorial chemistry – capable of providing compound libraries with >100,000 members – and the ability to synthesize hundreds of molecules in parallel fueled the growth of large compound collections and demanded higher throughput methods in biological and pharmacological testing. In response to this need, automated HTS platform and lead optimization approaches were developed in the mid‐to‐late 1990s incorporating robotics, workstations, and new assay technologies using 96‐well, 384‐well, and 1536‐well microtiter plates and miniaturized assay volumes (<10 μL). In parallel, informatic tools to acquire, store, and analyze millions of data points were also developed. Automation coupled to powerful computing technologies was critical for success and served as a unique enabler to ensure the development and implementation of rigorous and reproducible bioassay methodologies. Many of the technologies and statistical tools that were developed within the pharmaceutical industry in collaboration with instrument and software vendors were retained as internal proprietary knowledge to drive projects in preclinical discovery (personal communications with D. Auld of the Novartis Institutes of Biomedical Research). A major goal was to develop and validate “automatable bioassays,” taking benchtop assays built in‐house or from the scientific literature and optimizing these for automated protocols. This goal also required significant assay and technology development, as many assays published in the scientific literature were not amenable to automation.

Some of the AGM chapters were originally developed as Validation Checklist and Guidelines for High‐Throughput Screening in 1995 and later as the Quantitative Biology Manual at Eli Lilly and Company and Sphinx Pharmaceuticals in the late 1990s. Contributions came from well over 100 internal scientists involved in drug discovery and development. The manual evolved continuously over time and became a valuable reference within Lilly Research Laboratories. The focus was on basic information about biochemical, cell‐based, and in vitro assay technologies that could be implemented to successfully screen drug targets and pathways against small molecule libraries. In addition, the manual addressed best practices in HTS scale‐up, assay operations, reagent selection, statistical tools for assay validation, and data analysis and management.

As the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Molecular Libraries Roadmap program developed in 2003,7, 8 discussions between the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) and Lilly management resulted in an agreement to publish this manual on the National Center for Chemical Genomics website at the NHGRI to share the information with academic scientists in the precompetitive space. The manual was ultimately released to share best practices in quantitative biology and guidelines for the development of robust assay methods with the drug discovery community as well as enhance academic‐industrial collaborations in translational biology and medicine. Additionally, the manual was intended to grow with the collective experiences and contributions from public and private research laboratories. The decision was prescient, particularly given that the Molecular Libraries Roadmap established a number of collaborative HTS centers in the United States that would require academic laboratories to propose and develop high‐quality screening assays. Sharing precompetitive knowledge contained in the AGM with academic screening laboratories and the wider scientific community was envisaged to remove barriers to robust discovery assay development, and act as a catalyst to advance translational science broadly.

As drug discovery technologies and methodologies continued to evolve, it was obvious that the manual required regular updates and the addition of new content. To accomplish this task, an informal steering group of scientists from the NHGRI‐National Center for Chemical Genomics and Eli Lilly was assembled to administer the updates. The steering group decided early on that wider participation from pharmaceutical and academic scientists would further enhance the value of the AGM. It was also decided that the AGM content should be managed by an editorial board. In 2012, the manual became part of an eBook collection on the NLM, NCBI Bookshelf. This platform had several advantages: (i) the ability to reach a worldwide audience; (ii) PubMed citations for the authors who contribute chapters; and (iii) the eBook chapter formats would be dynamic and, thus, allow for updates and edits to all chapters through a centralized submission process to maintain high quality and currency. The current AGM Editorial Board consists of 34 editors, most with over 20 years of experience in drug discovery and assay development from industry, academia, and various research institutes throughout the world (Figure 1). The editors hold monthly teleconferences to discuss updates of the material and plans for new chapters, which are peer‐reviewed prior to publication.

Figure 1.

Diversity of the Assay Guidance Manual Editorial Board. The content of the Assay Guidance Manual is managed by an editorial board of 34 members, most with over 20 years of experience in drug discovery and development. The editors work in different settings including industry, academia, and nonprofit research institutes.

CURRENT CONTENTS AND USAGE IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN

The unique content of the AGM, a source for best practices in robust assay development, is appealing to a growing audience of researchers interested in enabling early‐stage drug discovery projects. Many publication formats, such as printed journals and books, are static and, thus, not amenable to frequent updates. However, the dynamic eBook format allows for updates to existing chapters and growth of the AGM. As of December 2017, the AGM contains 46 chapters (up from the original 22 chapters) and a glossary of common drug discovery terms and definitions. In April of 2017, the AGM was accessed by 131 countries, with the majority of readers located in the United States, then United Kingdom, India, Germany, Canada, Australia, and Japan, respectively (Figure 2). An analysis of the domains accessing the AGM indicates that the majority of AGM users come from .net, .edu, and .com, with a minority coming from .gov and .org (Figure 3). Most readers from the .net domain are likely accessing the AGM from their personal computers and devices, whereas readers from .edu and .com domains are probably from academia and industry, respectively. Although all content is available online, individual chapters or the entire eBook can be freely downloaded as pdf files with the current version spanning 1,338 printed pages. Since the AGM was first published on the NCBI Bookshelf, worldwide access to the chapters has steadily increased from about 4,000 per month in 2012 to more than 30,000 per month in 2017 (Figure 4 a,b). The AGM chapters are organized into nine sections in the table of contents, including: (i) Considerations for Early Phase Drug Discovery; (ii) In Vitro Biochemical Assays; (iii) In Vitro Cell Based Assays; (iv) In Vivo Assay Guidelines; (v) Assay Artifacts and Interferences; (vi) Assay Validation, Operations, and Quality Control; (vii) Assay Technologies; (viii) Instrumentation; and (ix) Pharmacokinetics and Drug Metabolism.

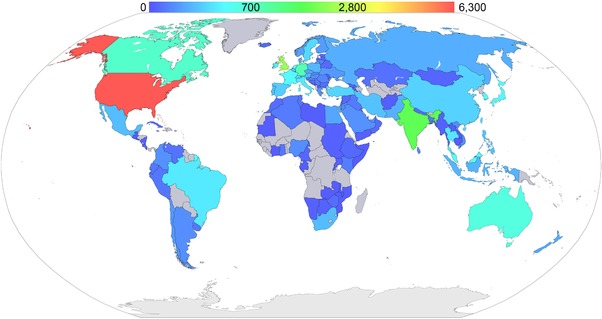

Figure 2.

Worldwide access to the Assay Guidance Manual (AGM). The AGM was accessed 39,839 times by readers in 131 countries during the month of April 2017. The heat map shows the amount of access per country ranging from low (dark blue) to high (red). The countries colored grey did not access the AGM in April 2017.

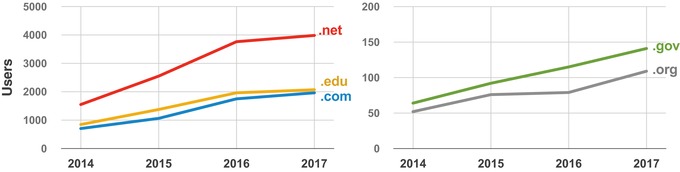

Figure 3.

Users of the Assay Guidance Manual (AGM) grouped by domain. The total number of AGM users in the United States during April are plotted according to domain over a period of 4 years from 2014 through 2017. Although usage is growing in all cases, the majority of AGM users come from .net, .edu, and .com domains.

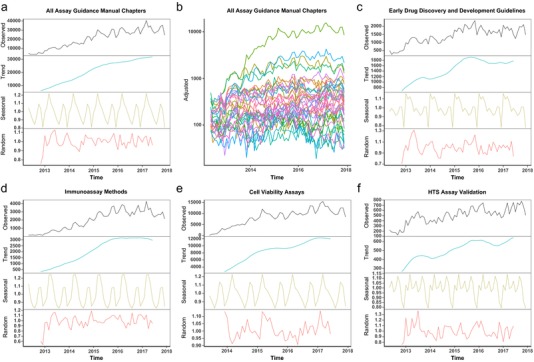

Figure 4.

Worldwide usage of the Assay Guidance Manual (AGM) since 2012. Usage of the AGM has been steadily growing since it was published as an eBook on the National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information Bookshelf in 2012. Time series decomposition (using a simple moving average (SMA) with a multiplicative model61) was applied to the access counts for the entire AGM and selected chapters. Individual components of the decompositions are shown in each plot, with the y‐axis for all plots representing access counts. The trend component was computed using an SMA with a 12‐month window. The seasonal component was derived from the observed time series by dividing by the trend component. The random component was computed by dividing the observed time series by the seasonal, followed by dividing by the trend components. (a) The total monthly access among all AGM chapters has steadily increased to >30,000 in 2017. (b) A plot of seasonally adjusted web access for all 46 chapters of the AGM, each shown as a different color. (c) Among the most widely‐accessed chapters is Early Drug Discovery and Development Guidelines: For Academic Researchers, Collaborators, and Start‐up Companies, which was accessed an average of 1,776 times per month in 2017. (d) The Immunoassay Methods chapter came from the original Eli Lilly and Company Quantitative Biology Manual and was the second most accessed chapter in 2017. (e) The most popular chapter of the AGM is Cell Viability Assays, which was accessed an average of 11,895 times per month in 2017. (f) The high‐throughput screening (HTS) Assay Validation chapter also originated from the Eli Lilly and Company Quantitative Biology Manual and has continued to grow in popularity over the past 6 years.

The Early Phase Drug Discovery section of the AGM contains a chapter that provides guidelines for planning early drug discovery and development projects and is particularly intended to benefit academic researchers, nonprofits, and other life science research companies.9 The development of therapeutic hypotheses, validation of targets and pathways, and proof‐of‐concept criteria are discussed. Three types of projects are highlighted, including: developing a new chemical entity, repurposing of marketed drugs, and applying novel platform technology to improve delivery of currently marketed drugs. In addition to summarizing the scopes, estimated timelines, and critical decision points for these projects, the chapter provides details about the types of assays that should be conducted and cost estimates at various stages. As such, the chapter can serve as an excellent reference for project planning and for developing grant proposals. This chapter was first introduced along with the eBook format on 1 May 2012, and has been updated several times to reflect current costs and best practices, most recently in 2016. In 2017, it was the fourth most popular chapter and was accessed an average of 1,776 times per month (Figure 4 c).

The In Vitro Biochemical Assays section of the AGM consists of 10 chapters, nine of which were first published on 1 May 2012. The chapters cover a variety of topics from reagent validation10 and enzymatic11 or immunoassay12 methods, to more specific target types, such as receptors,13, 14 kinases,15 proteases,16 histone acetyltransferases,17 and protein‐protein interactions.18 Additionally, methods are described to determine the mechanism of action for drug candidates against a target enzyme.19 Five of these chapters are primarily material from the original Eli Lilly and Company Quantitative Biology Manual for internal use. Notably, these five chapters have remained popular among readers over the past 6 years and readership is continuing to grow for three of them: Mechanism of Action Assays for Enzymes,19 Receptor Binding Assays for HTS and Drug Discovery,13 and Protease Assays.16 The other two original chapters, Immunoassay Methods 12 (Figure 4 d) and Basics of Enzymatic Assays for HTS,11 were the second and third most highly accessed chapters of the AGM in 2017, respectively. Although Immunoassay Methods was updated in late 2014, the other four chapters have remained unmodified since 2012. Thus, the important and fundamental information covered in the original chapters remains relevant and of high interest to the drug discovery community.

The largest section of the AGM is the In Vitro Cell Based Assays section, which comprises 19 chapters. This section has grown from the initial seven chapters that were introduced in 2012. Collectively the chapters cover concepts relevant throughout the discovery pipeline, from the identification and validation of targets and reagents20, 21, 22 to advanced 3D model systems and models that can be applied for safety and toxicity assessments.23, 24 Both reproducibility and validation of assays and reagents are critical for a successful discovery campaign, so a chapter was introduced in 2013 about the authentication of human cell lines that was co‐authored by Yvonne Reid of the ATCC.20 A number of the chapters address assays and technologies that can be applied for primary and secondary screening against targets as diverse as protein‐protein interactions, ion channels, and G‐protein‐coupled receptors.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Some of the assay methodologies can be applied to interrogate the regulation of signaling pathways.31, 32, 33 High‐content imaging is a powerful methodology that enables multiplexed readouts from cell‐based model systems. Four chapters focus on such methodologies and their applications to HTS.32, 34, 35, 36 Emerging methodologies are also covered, such as applications of cellular thermal shift assays to HTS37 and the use of engineered nucleases in genomic screening.22 The most highly accessed chapter in the AGM eBook is Cell Viability Assays,38 which was first published in 2013 and has continued to attract readers since that time (Figure 4 e). In 2017, Cell Viability Assays was accessed an average of nearly 12,000 times per month. The chapter describes a variety of methods that can be applied to estimate the number of viable cells using a plate reader, including methods that can be multiplexed with other assays and readouts. The remarkable interest in this chapter is likely due to the increase in use and significance of phenotypic screening and the universal relevance of this information to biological discovery projects.39

Later stages of discovery currently require the use of animal models and the In Vivo Assay Guidelines section of the AGM provides guidelines for the design, development, and statistical validation of in vivo assays,40 and methods to quantify receptor occupancy in rodent models.41 Additionally, the Pharmacokinetics and Drug Metabolism section was recently introduced with a chapter that provides guidelines for in vitro and in vivo assessments of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination and PK properties of lead candidates.42 More chapters will be introduced on these topics as there is considerable interest in investigational new drug (IND)‐enabling studies among many academic and public research institutions.

There is considerable attention to reproducibility in translating basic discovery experiments from published data into discovery projects.43 Contributions to irreproducible results, artifactual bioactivity, and poorly tractable bioactivity can include assay reagents, data analysis methods, test compounds, instrumentation, and contaminants. Compound‐mediated assay interferences can be highly reproducible yet intractable sources of bioactivity due to either nonspecific compound mechanisms of action or to compound interference with assay readouts.44, 45 The amount of time and resources invested in follow‐up studies of irreproducible false‐positives as well as intractable or artifactual mechanisms of bioactivity can substantially reduce the productivity of a discovery program, but more importantly represents lost opportunity costs. The Assay Artifacts and Interferences section was introduced in 2015 to describe sources of assay artifacts along with strategies to mitigate them. The first chapter to be introduced, Assay Interference by Chemical Reactivity,46 was highlighted in “In The Pipeline,” Derek Lowe's blog on drug discovery and the pharma industry.47 Additional chapters focus on interferences associated with fluorescence and absorbance,48 luciferase reporters,49 and chemical aggregation,50 but more importantly, their identification and mitigation.

Three of the five chapters comprising the Assay Validation, Operations and Quality Control section originated in the Eli Lilly and Company Quantitative Biology Manual: Data Standardization for Results Management,51 HTS Assay Validation,52 and Assay Operations for SAR Support.53 Interestingly, the rate of viewership continues to increase for all three chapters and is shown for the HTS Assay Validation chapter in Figure 4 f. Data analysis templates are available for download from the chapters: HTS Assay Validation, Assay Operations for SAR Support, and Minimum Significant Ratio (MSR) – A Statistic to Assess Assay Variability.54 These tools allow researchers to perform different types of analysis procedures, such as plate uniformity and variability assessments or evaluating reproducibility and robustness of screening results that are detailed in the chapters. In particular, the template tools for MSR evaluation have been useful toward understanding and adoption of this less familiar parameter. Briefly, the MSR reflects the intrinsic ability of a structure activity relationship (SAR) assay to determine whether the potency (concentration at half‐maximal inhibition or half‐maximal effective concentration) measurements of any two compounds within n‐fold are meaningful.55, 56 A robust SAR assay will have an MSR of 3, whereas a weak assay might have a higher MSR >5. This statistical thinking is particularly important to medicinal chemists and pharmacologists during SAR to determine if the results from a screening assay allow for a robust differentiation and rank ordering of compounds. Such analyses also indicate whether the assay is even capable of guiding meaningful improvements to the potency. The MSR concept is also applied as a practical quality control tool on the reference (positive control) compounds for proactively detecting specific assay runs with significant drift or high variability. Another chapter in this section provides methods to describe and categorize chemical biology and drug screening assays and their results.57

Instrumentation is an evolving area that enables new fundamental measurements, methodologies, pushes detection limits, and catalyzes discoveries. The Instrumentation section of the AGM includes two chapters that describe basic features of equipment and instrumentation with calculations that are commonly utilized for HTS.58, 59 The Basics of Assay Equipment and Instrumentation for High Throughput Screening chapter has been particularly accessed by users coming from the .edu domain.

ASSAY DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT WORKSHOPS

The worldwide usage of the AGM demonstrated substantial interest in assay development methods among the scientific community and led to the development of an Assay Guidance Workshop for High‐Throughput Screening and Lead Discovery. The AGM eBook serves as a foundation for this workshop series, which is led primarily by members of the AGM Editorial Board. Most of the instructors have 20–30 years of experience in the field of drug discovery and preclinical therapeutic development. Ten workshops have been conducted, featuring both single‐day and 2‐day agendas with 5–17 lectures (Table 1). All workshops emphasize the importance of assays in guiding and defining the success of a preclinical discovery program and highlight the AGM as a resource. Specialized lectures focus on topics such as: target validation, physiologically relevant models, the development and implementation of biochemical and cell‐based assays, analytical technologies, mitigation of assay artifacts and interferences, lead selection and optimization, safety and toxicity assays, the assessment of PK and pharmacodynamic properties of lead compounds, as well as assay statistics and data analysis strategies. Additional lecture topics have included: the use of a design of experiments approach for assay development, advanced 3D model systems, label‐free HTS assays with mass spectrometry, high‐content screening, and biophysical methodologies for evaluating target engagement. Some workshops have offered special topic sessions, hands‐on data analysis training, and laboratory tours with demonstrations of equipment. The goal of each workshop is to provide participants with a broad, practical perspective on assay development so that they can (i) improve drug discovery or molecular probe development projects, and know where to find further information, (ii) identify reagents, instrumentation, and methods that are well‐suited to robust assays, (iii) be able to apply robust primary, orthogonal, and counter assays to a particular biological target, and (iv) understand critical data analysis concepts. Additionally, participants are provided with opportunities to seek practical advice about their own areas of interest.

Table 1.

Assay guidance workshop for high‐throughput screening and lead discovery

| Date | Location | Lectures | Organizer(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 February 2015 | Rockville, MD | 5 | National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

| 17 July 2015 | College Park, MD | 7 | US Food and Drug Administration, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

| 23 January 2016 | San Diego, CA | 9 | Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

| 5–6 April 2016 | College Park, MD | 10 | US Food and Drug Administration, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

| 27 October 2016 | Madison, WI | 9 | Promega, International Chemical Biology Society, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

| 4 February 2017 | Washington, DC | 9 | Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

| 7 August 2017 | Potomac, MD | 10 | National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

| 23 October 2017 | Chapel Hill, NC | 12 | UNC Catalyst for Rare Diseases, Promega, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

| 3 February 2018 | San Diego, CA | 9 | Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

| 26–27 March 2018 | Potomac, MD | 17 | National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

Ten workshops have been held in locations throughout the United States since February 2015. Both single‐day and 2‐day agendas have included between 5 and 17 lectures. Many of the events were co‐organized with government, industry, and academic partners in addition to international conferences.

Although the workshop sizes have ranged from 23 to 169 participants (Figure 5 a), the current target number is about 40 participants. It was observed that smaller group sizes enhance learning by increasing the discussion and interactions between the instructors and participants. Although the majority of participants are from the United States, individuals have also traveled from 14 countries (Figure 5 b). The target audience is individuals involved in bioassay development for the discovery of drug candidates and chemical probes. Participants have come from academic, industry, and government sectors (Figure 5 c) with experience levels ranging from students and early career professionals to physicians, engineers, and well‐established investigators. The high diversity in experiences among both the lecturers and participants, as well as the sectors and locations from which they work, typically leads to very interesting questions and discussions. Some of these discussions have resulted in the modification of lectures, introduction of new lecture topics, and growth of the AGM eBook.

Figure 5.

Participation in the Assay Guidance Workshop for High‐Throughput Screening and Lead Discovery. Ten assay guidance workshops have been conducted since 2015. (a) The number of participants in the workshops have varied between 23 and 169, with most workshops having <50. It was observed that open discussions and learning are enhanced with smaller group sizes. (b) A total of 549 individuals have participated in all 10 workshops and come from 14 countries in addition to the United States. (c) Participants of the 10 workshops come from a variety of settings, including industry, academia, and government. The first workshop and two largest workshops were only advertised to employees of the US Government, which is why the majority of the workshop participants are from the government. DOD, Department of Defense; EPA, Environmental Protection Agency; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NIST, National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Since 2015, three workshops per year have been held in locations throughout the United States (Table 1). The inaugural workshop in February 2015 was held at the NCATS laboratories in Rockville, MD, and featured five lectures and a tour of the laboratory equipment. Two subsequent workshops were held in 2015 and 2016 at the US Food and Drug Administration campus in College Park, MD. The workshop has been offered as a short course by the international Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening annual conference since 2016 in both San Diego, CA, and Washington, DC. In 2016, a workshop was held in association with the International Chemical Biology Society conference on Translational Chemical Biology at the Promega campus in Madison, WI. In 2017, a workshop was held in collaboration with Promega and the UNC Catalyst for Rare Diseases at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, NC. Workshops have also been held in Potomac, MD, in 2017 and 2018. The combination of limiting workshops to small groups and holding only three events annually in a single country restricts the accessibility of this educational format. In order to extend the workshop material to a wider audience, a collection of high‐quality video recordings of lectures has been developed and is freely available online (https://ncats.nih.gov/agm-video).

FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS AND ROLE IN TRAINING DISCOVERY SCIENTISTS

The AGM is established as a world‐class resource for guidelines and best practices to advance translational sciences; the preclinical development of novel therapeutics. Both the eBook and the workshop series have been highlighted in a recent article by the Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening Director of Education, Steve Hamilton.60 The AGM usage metrics indicate growing interest in assay development for HTS and lead optimization among researchers within academic, government, and industrial sectors. It is important to be aware of new technologies, methodologies, reporters, reagents, and cell‐based model systems. In addition, concerns about improving reproducibility and tractability are shared by researchers worldwide and have led to important discussions about data analysis, appropriate controls, reagent validation, methodology and study designs, appropriate model systems, and assay artifacts. To address this evolving landscape and enable researchers with the necessary knowledge to successfully advance the development of novel therapeutics, the AGM editors are actively increasing the scope and depth of the eBook, developing educational videos to supplement the chapters, and enhancing the workshops.

It is important for the AGM eBook to continue as a reliable source for up‐to‐date guidelines and best practices for robust assay development in quantitative biology and pharmacology as new topics emerge. Existing chapters will be updated to include new technologies, techniques, and trends in the field. Currently, there are nearly 30 new chapters in development that span a broad range of topics, from guidelines for project management and reviewers of HTS screening grant proposals to optogenetics and immunogenicity assays. Many of the chapters will fit into current sections of the AGM. For instance, there are three more chapters in development for the Assay Artifacts and Interferences section. Three chapters are also in the works for the Instrumentation section with a focus on automation and implementation of methodologies for screening with drug combinations. Six chapters are in development for the In Vitro Cell Based Assays section, two of which focus on stem cell pluripotency assays and guidelines for scaling up pluripotent stem cell cultures for HTS. Some of the new content will require the addition of new sections. For instance, in 2018 a Safety and Toxicity Assays section will be introduced to accommodate two new chapters, including a complementary chapter to the Cell Viability Assays chapter that will describe a variety of in vitro methods to measure dead cells. Another section will focus on the importance of medicinal chemistry in compound bioactivity analysis and lead optimization and will include chapters that summarize critical medicinal chemistry concepts for biologists and other topics, such as quantitative structure–activity relationship modeling. Related to this will be a new section focusing on biophysical methodologies for characterizing target engagement by lead molecules.

The AGM chapters will be enhanced by the introduction of educational videos about specialized concepts, methodologies, instrumentation, and data analysis procedures that support HTS and lead discovery. For example, some chapters describe specialized automation‐compatible equipment not available in most research laboratories. Knowledge of such equipment is critical for the successful adaptation of assay procedures from the benchtop to a fully automated workstation, which is a common bottleneck in preclinical research. An increasing number of researchers are actively developing assays for HTS as a collaboration. In such cases, the researchers developing the assays might not operate the HTS equipment, but such knowledge would benefit the collaboration. These videos will also be helpful to a variety of other individuals, including students, professionals working across disciplines, and reviewers of HTS grant proposals.

The Assay Guidance Workshop for High‐Throughput Screening and Lead Discovery offers a unique training opportunity for students and professionals by covering practical aspects of drug discovery that are not as accessible from classrooms or the literature. The workshop content is further enhanced by the diverse backgrounds of the lecturers and participants who are able to frame concepts from different perspectives during formal and informal discussions. The engagement between scientists from different sectors frequently focuses on solving research problems and sometimes initiating new partnerships. Thus, the workshops enhance academic‐industrial collaborations in translational biology and medicine. Although the majority of workshops have had single‐day agendas, 2‐day events with wider scopes will be held more frequently in the future. Additionally, hands‐on data analysis sessions will be incorporated more often so that participants can immediately learn to apply concepts from the lectures. This will enable participants to readily incorporate new analysis strategies within their own research projects. The series of online workshop videos will continue to grow with the diversity and scope of the lectures. This will benefit researchers who are unable to attend in person or previous participants who would like to review some aspects.

CONCLUSION

The AGM was initiated as a guide for therapeutic project teams within a major pharmaceutical company, based on internal proprietary knowledge assembled from experts spanning multiple therapeutic disciplines. Recognition that the value of this manual resulted from the combination of experiences contributed by more than 100 scientists was part of the rationale for releasing its contents to the public. The early vision was that additional contributions from drug discovery scientists worldwide would add substantial expertise and value. Furthermore, uniting translational scientists in a precompetitive space would contribute to drug discovery broadly and benefit everyone. The AGM is intended to serve as a vehicle for the harmonization of assay design concepts, definitions, reproducible validated methodologies, and “statistical thinking,” which is a combination of good science and common sense with an understanding of variability. Certainly, both the growing usage of the eBook and popularity of the workshop series demonstrate a strong interest in robust biologically, physiologically, and pharmacologically relevant assays for therapeutic development. New discoveries and advances in technologies, methodologies, instrumentation, and data analysis strategies are providing exciting opportunities to support the development of innovative therapeutics. However, emerging priorities in human health (e.g., Zika virus, or the opioid addiction crisis) in addition to limitations in time and research budgets place increasing demands on therapeutic discovery projects. Sharing best practice guidelines will help all researchers do the best possible science; however, more contributors to the AGM will be required to keep pace with the new discoveries and advances. Together the global community can build the AGM as an international treasure of publicly available information to accelerate the translation of basic research to therapeutics through the training of scientists.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no competing interests for this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jeff Beck, Charles “Pepper” Bonney, Penny Burgoon, Laura Carter, Nolan Chase, Adrian Choice, Neal Cosby, Janice Crum, Suzanne C. Fitzpatrick, Nicholas Gelardi, C. Taylor Gilliland, Sam Grammer, Steven Hamilton, David Hanley, Nicole Haselwander, Michael Hoffmann, Sandy Ismail, Anne Ketter, Ann Knebel, Emet LaBoone, Theresa Lamotte, A. Renee Madden, Cindy McConnell, Dave Morris, Henrike Nelsen, Jim Ostell, Kim Pruitt, Melvin Reichman, Laura Richards, Meghan Schofield, Hannah Scott, Stephanie Shea, Geoff Spencer, Ashley Stewart, Amy Wilkinson, and Adam Yasgar for their support of the AGM.

Source of Funding

This work was supported by the NCATS Division of Pre‐Clinical Innovation Intramural Program and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Library of Medicine. Authors also acknowledge the NIGMS R13 grant support (5U13MH088095‐02) for the annual editor's conference on Development of Robust Experimental Assay Methods (aDREAM) from 2011–2014.

Nathan P. Coussens, G. Sitta Sittampalam, and Rajarshi Guha contributed equally to this work.

This article has been contributed to by US Government employees and their work is in the public domain in the USA.

Contributor Information

Nathan P. Coussens, Email: coussensn@mail.nih.gov

G. Sitta Sittampalam, Email: gurusingham.sittampalam@nih.gov.

References

- 1. Ledford, H. Translational research: 4 ways to fix the clinical trial. Nature. 477, 526–528 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fruchter, R. , Ahmad, M. , Pillinger, M. , Galeano, C. , Cronstein, B.N. & Gold‐von Simson, G. Teaching targeted drug discovery and development to healthcare professionals. Clin. Transl. Sci. 11, 277–282 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gilliland, C.T. , Sittampalam, G.S. , Wang, P.Y. & Ryan, P.E. The translational science training program at NIH: introducing early career researchers to the science and operation of translation of basic research to medical interventions. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Edu. 45, 13–24 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reese, R.A. Does significance matter? Significance. 1, 39–40 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Antunovic, B. et al Statistical significance and biological relevance. EFSA J. 9, (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Austin, C.P. , Brady, L.S. , Insel, T.R. & Collins, F.S . NIH molecular libraries initiative. Science. 306, 1138–1139 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schreiber, S.L. et al Advancing biological understanding and therapeutics discovery with small‐molecule probes. Cell. 161, 1252–1265 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Strovel, J. et al Early drug discovery and development guidelines: For academic researchers, collaborators, and start‐up companies Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scott, J.E. & Williams, K.P . Validating identity, mass purity and enzymatic purity of enzyme preparations Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brooks, H.B. et al Basics of enzymatic assays for HTS Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cox, K.L. et al Immunoassay methods Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Auld, D.S. et al Receptor binding assays for HTS and drug discovery Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeLapp, N.W. , Gough, W.H. , Kahl, S.D. , Porter, A.C. & Wiernicki, T.R . GTPgammaS binding assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glickman, J.F . Assay development for protein kinase enzymes Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang, G . Protease assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gadhia, S. , Shrimp, J.H. , Meier, J.L. , McGee, J.E. & Dahlin, J.L . Histone acetyltransferase assays in drug and chemical probe discovery Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arkin, M.R. , Glicksman, M.A. , Fu, H. , Havel, J.J. & Du, Y. Inhibition of protein‐protein interactions: non‐cellular assay formats Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Strelow, J. et al Mechanism of action assays for enzymes Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reid, Y. , Storts, D. , Riss, T. & Minor, L . Authentication of human cell lines by STR DNA profiling analysis Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martin, S. et al Cell‐based RNAi assay development for HTS Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Costa, J.R. et al Genome editing using engineered nucleases and their use in genomic screening Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kijanska, M. & Kelm, J. In vitro 3D spheroids and microtissues: ATP‐based cell viability and toxicity assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lamore, S.D. , Scott, C.W. & Peters, M.F . Cardiomyocyte impedance assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Priest, B.T. et al Automated electrophysiology assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arkin, M.R. et al FLIPR assays for GPCR and ion channel targets Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McManus, O.B. et al Ion channel screening Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang, T. et al Measurement of beta‐arrestin recruitment for GPCR targets Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang, T. , Li, Z. , Cvijic, M.E. , Zhang, L. & Sum, C.S. Measurement of cAMP for galphas‐ and galphai protein‐coupled receptors (GPCRs) Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wade, M. et al Inhibition of protein‐protein interactions: cell‐based assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garbison, K.E. , Heinz, B.A. & Lajiness, M.E . IP‐3/IP‐1 assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Trask, O.J. Jr. Nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐kappaB) translocation assay development and validation for high content screening Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Garbison, K.E. , Heinz, B.A. , Lajiness, M.E. , Weidner, J.R. & Sittampalam, G.S . Phospho‐ERK assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bray, M.A. & Carpenter, A . Advanced assay development guidelines for image‐based high content screening and analysis Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Buchser, W. et al Assay development guidelines for image‐based high content screening, high content analysis and high content imaging Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 36. Al‐Ali, H. , Blackmore, M. , Bixby, J.L. & Lemmon, V.P . High content screening with primary neurons Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Axelsson, H. , Almqvist, H. , Seashore‐Ludlow, B. & Lundback, T. Screening for target engagement using the cellular thermal shift assay ‐ CETSA Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Riss, T.L. et al Cell viability assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Swinney, D.C. & Anthony, J. How were new medicines discovered? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 507–519 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Haas, J. et al In vivo assay guidelines Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jesudason, C.D. , DuBois, S. , Johnson, M. , Barth, V.N. & Need, A.B. In vivo receptor occupancy in rodents by LC‐MS/MS Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chung, T.D.Y. , Terry, D.B. & Smith, L.H . In vitro and in vivo assessment of ADME and PK properties during lead selection and lead optimization ‐ guidelines, benchmarks and rules of thumb Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Freedman, L.P. , Cockburn, I.M. & Simcoe, T.S . The economics of reproducibility in preclinical research. PLoS Biol. 13, e1002165 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arrowsmith, C.H. et al The promise and peril of chemical probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 536–541 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thorne, N. , Auld, D.S. & Inglese, J. Apparent activity in high‐throughput screening: origins of compound‐dependent assay interference. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 14, 315–324 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dahlin, J.L. , Baell, J. & Walters, M.A . Assay interference by chemical reactivity Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lowe, D . Screen carefully. In the Pipeline. <http://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2015/11/11/screen-carefully>. (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 48. Simeonov, A. & Davis, M.I . Interference with fluorescence and absorbance Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Auld, D.S. & Inglese, J . Interferences with luciferase reporter enzymes Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Auld, D.S. , Inglese, J. & Dahlin, J.L . Assay interference by aggregation Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Campbell, R.M. et al Data standardization for results management Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Iversen, P.W. et al HTS assay validation Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Beck, B. et al Assay operations for SAR support Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Haas, J.V. , Eastwood, B.J. , Iversen, P.W. , Devanarayan, V. & Weidner, J.R . Minimum significant ratio ‐ a statistic to assess assay variability Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Eastwood, B.J. et al The minimum significant ratio: a statistical parameter to characterize the reproducibility of potency estimates from concentration‐response assays and estimation by replicate‐experiment studies. J. Biomol. Screen. 11, 253–261 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Iversen, P.W. , Eastwood, B.J. , Sittampalam, G.S. & Cox, K.L. A comparison of assay performance measures in screening assays: signal window, Z' factor, and assay variability ratio. J. Biomol. Screen. 11, 247–252 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vempati, U.D. & Schurer, S.C. Development and applications of the bioassay ontology (BAO) to describe and categorize high‐throughput assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jones, E. , Michael, S. & Sittampalam, G.S . Basics of assay equipment and instrumentation for high throughput screening Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kahl, S.D. , Sittampalam, G.S. & Weidner, J . Calculations and instrumentation used for radioligand binding assays Assay Guidance Manual. (Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hamilton, S . Effective drug discovery begins with the right assay. <https://www.slas.org/eln/effective-drug-discovery-begins-with-the-right-assay/> (2015).

- 61. Kendall, M. & Stuart, A. The Advanced Theory of Statistics. Vol 3 <http://www.scirp.org/(S(351jmbntvnsjt1aadkposzje))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=749124> (1983). [Google Scholar]