Abstract

Since its clinical introduction in 1998, the topoisomerase I inhibitor irinotecan has been widely used in the treatment of solid tumors, including colorectal, pancreatic, and lung cancer. Irinotecan therapy is characterized by several dose-limiting toxicities and large interindividual pharmacokinetic variability. Irinotecan has a highly complex metabolism, including hydrolyzation by carboxylesterases to its active metabolite SN-38, which is 100- to 1000-fold more active compared with irinotecan itself. Several phase I and II enzymes, including cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A, are involved in the formation of inactive metabolites, making its metabolism prone to environmental and genetic influences. Genetic variants in the DNA of these enzymes and transporters could predict a part of the drug-related toxicity and efficacy of treatment, which has been shown in retrospective and prospective trials and meta-analyses. Patient characteristics, lifestyle and comedication also influence irinotecan pharmacokinetics. Other factors, including dietary restriction, are currently being studied. Meanwhile, a more tailored approach to prevent excessive toxicity and optimize efficacy is warranted. This review provides an updated overview on today’s literature on irinotecan pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacogenetics.

Key Points

| Irinotecan metabolism is complex due to the involvement of many enzymes and transporters, and is therefore prone to drug–drug interactions. Prior to starting with irinotecan chemotherapy, patients should be evaluated for possible interactions with comedication. |

| Single nucleotide polymorphisms in several drug metabolizing enzymes (e.g. uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase [UGT] 1A1, UGT1A7, UGT1A9) and drug transporters (e.g. ATP-binding cassette [ABC] B1, ABCC1) have been reported to be significantly associated with irinotecan toxicity. Caucasian patients should be screened for UGT1A1*28 and Asian patients for UGT1A1*6 in advance of irinotecan treatment as these polymorphisms are common in those populations and dosing can be personalized if UGT1A1 functioning is constitutionally altered. |

| Despite existing genotype-based dosing guidelines, upfront UGT1A1 genotyping is not yet routinely performed in patients starting with irinotecan chemotherapy. |

Introduction

Irinotecan (CPT-11) is a camptothecin derivative that demonstrates anticancer activity in many solid tumors. Currently, it is widely used in the treatment of colorectal, pancreatic, and lung cancer. Irinotecan is the prodrug for SN-38, which inhibits topoisomerase-I, an enzyme involved in DNA replication [1, 2]. SN-38 is 100- to 1000-fold more cytotoxic than irinotecan, and its exposure is highly variable [3]. SN-38 is inactivated by further enzymatic conversion into SN-38 glucuronide (SN-38G).

Pharmacokinetics

Distribution

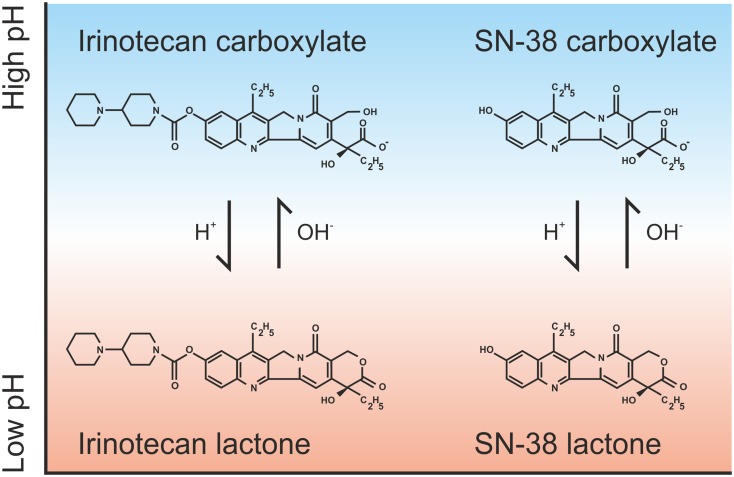

Irinotecan is a hydrophilic compound with a large volume of distribution estimated at almost 400 L/m2 at steady state [4]. At physiological pH, the lactone-ring of irinotecan and SN-38 can be hydrolyzed to a carboxylate isoform (Fig. 1). Consequently, a pH-dependent equilibrium between these forms exists [5]. As only the lactone form has antitumor activity, a small change in pH could alter the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of irinotecan [6]. However in plasma the carboxylate form of irinotecan and the lactone form of SN-38 dominate [7, 8]. This could be explained by a higher tissue distribution of irinotecan lactone and the preferential binding of SN-38 lactone to plasma proteins [4, 9]. Conversion of irinotecan lactone to carboxylate within the circulation is rapid, with an initial half-life of between 9 and 14 min, which results in a 50% reduction in irinotecan lactone concentration after 2.5 h, compared with end of infusion (66 vs. 35%) [4, 7, 8].

Fig. 1.

pH-dependent equilibrium of irinotecan and SN-38 isoforms

After the end of drug infusion, a rapid decrease in irinotecan plasma concentrations is seen. Peak concentrations of SN-38 are reached within 2 h after infusion [8]. Irinotecan is assumed to exhibit linear pharmacokinetics because of the correlation between dose and systemic exposure, which is highly variable between patients [8]. In plasma, the majority of irinotecan and SN-38 is bound to albumin, which has a stronger binding capacity for the more hydrophobic active metabolite, and albumin also stabilizes the lactone forms of irinotecan and SN-38 [10]. In blood, SN-38 is almost completely bound, with two-thirds located in platelets and, predominantly, red blood cells [11]. The binding constant of SN-38 with erythrocytes is almost 15-fold higher than that of irinotecan [11].

Thus far, several population pharmacokinetic models of irinotecan have been developed. All models confirmed the large interindividual variability in pharmacokinetic parameters of approximately 30%. In general, a three-compartmental model for irinotecan and a two-compartmental model for SN-38 is assumed [4, 12–16]. A mean SN-38 distribution half-life was estimated to be very short (approximately 8 min) [13]. Several models showed a second peak in the SN-38 plasma area under the curve (AUC), which was explained by an enterohepatic re-circulation of SN-38. SN-38 is reabsorbed after intestinal deconjugation of SN-38G by (bacterial) β-glucuronidases [15]. Alternatively, release of SN-38 from erythrocytes has also been proposed to cause this second plasma peak [17].

Metabolism

Metabolism by Carboxylesterases and Butyrylcholinesterase

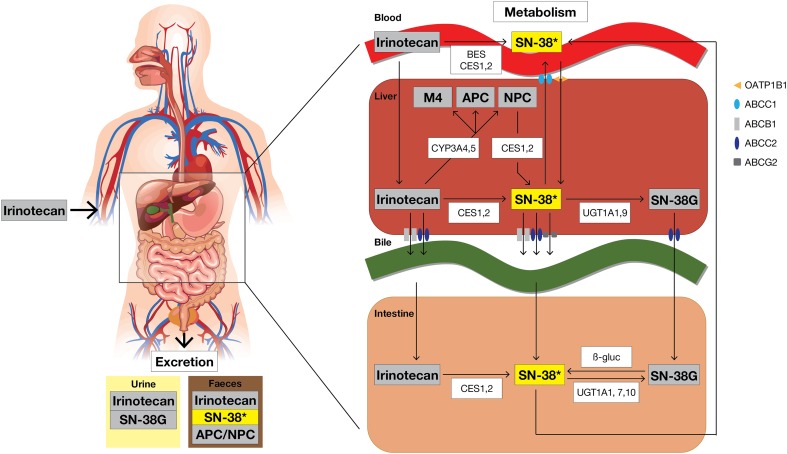

The prodrug irinotecan is hydrolyzed into the active metabolite SN-38 by two isoforms of carboxylesterases (CES1 and 2) and butyrylcholinesterase in the human body (Fig. 2) [18, 19]. CES1 and CES2 are localized in liver, colon, kidney, and blood cells, while butyrylcholinesterase is mainly found in plasma [20]. Conversion by these esterases mainly occurs intrahepatically and is a relatively slow and inefficient process as only 2–5% of irinotecan is converted into SN-38 [12, 18]. CES2 has a 12.5-fold higher affinity for irinotecan than CES1 and is therefore the predominant enzyme in this conversion [21–23]. In addition, this process also occurs in blood, where butyrylcholinesterase has a sixfold higher activity than CES [20]. After conversion, SN-38 is actively transported into the liver by the organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP) 1B1 transporter (Fig. 2) [24].

Fig. 2.

Irinotecan metabolism and excretion. The main excretion routes of all metabolites are depicted. * Active metabolite. CES carboxylesterase, BES butyrylcholinesterase, CYP cytochrome P450 enzymes, UGT uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase, β-gluc β-glucuronidase

Many studies have investigated intratumoral CES activity, by which irinotecan can be activated at the site of action. Indeed, the amount of CES activity could be related to irinotecan efficacy, although preclinical work showed conflicting results [25–30]. Many preclinical studies have been performed to selectively increase the intratumoral CES activity with a virus or engineered stem cells, thereby aiming to increase irinotecan efficacy [31–38]. Although a few studies could indeed reverse irinotecan resistance in vitro and in mice, this mechanism has not yet been investigated in a clinical setting.

To our knowledge, no clinically relevant drug–drug interactions (DDIs) involving CES have been reported for irinotecan, although both inhibitors and inducers of CES have been described, which could potentially influence the rate of irinotecan conversion to SN-38 [39].

Metabolism by Uridine Diphosphate Glucuronosyltransferases

SN-38 is inactivated via glucuronidation to SN-38G by uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) and excreted into the bile [40, 41]. Several UGT subtypes are involved in the hepatic (UGT1A1, UGT1A9) and extrahepatic (UGT1A1, UGT1A7, UGT1A10) conversion of SN-38, of which UGT1A1, UGT1A7 and UGT1A9 are the major isoenzymes [42–46]. SN-38G is formed almost directly after SN-38 formation, explaining the short half-life of SN-38 [47]. Plasma concentrations of SN-38G are the highest among all irinotecan metabolites, suggesting a highly efficient glucuronidation rate of SN-38 into SN-38G [4]. UGT1A1 also conjugates bilirubin, and a significant correlation between SN-38 and bilirubin glucuronidation has been observed [42]. In addition, patients genetically predisposed with decreased UGT1 activity, e.g. in Gilbert’s syndrome, are at higher risk for severe toxicity when treated with irinotecan [48]. In addition, many other UGT polymorphisms have been described and their influence on irinotecan pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics is summarized in Sect. 4.

Metabolism by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes

Irinotecan is also metabolized by intrahepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, i.e. CYP3A4 and CYP3A5, into inactive metabolites—APC and NPC [49]. In contrast to APC, NPC can be converted to SN-38 by CES1 and CES2 in the liver, but to a lesser amount than irinotecan [50]. The importance of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 in irinotecan metabolism is underlined by the strong correlation between irinotecan and midazolam clearance [51]. Midazolam is an important CYP3A probe drug, and we previously conducted a randomized clinical trial aiming to individualize irinotecan dosing by use of a CYP3A4 phenotype-based algorithm. By dosing on this algorithm, the interindividual variability in irinotecan and SN-38 exposure dramatically reduced compared with conventional dosing [52]. In addition, smoking, some herbal supplements, and comedication are known to induce or inhibit CYP3A enzymes, resulting in interactions with irinotecan, which are summarized in more detail in Sect. 2.5.

Metabolism by β-Glucuronidases

As previously mentioned, SN-38G can be deconjugated into SN-38 by β-glucuronidases produced by intestinal bacteria, which could result in an enterohepatic circulation of SN-38 [15, 53–55]. In addition, β-glucuronidase activity has been correlated to intestinal damage and diarrhea in rats/mice, which could (potentially) be reduced by inhibiting β-glucuronidase with antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) or amopaxine [56, 57]. Nonetheless, attempts to reduce β-glucuronidase activity by neomycin did not significantly alter the irinotecan pharmacokinetic profile in patients [58].

Elimination

The clearance of irinotecan is mainly biliary (66%) and independent of dose, estimated at 12–21 L/h/m2 [59, 60]. Irinotecan is transported into the bile by several ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (i.e. ABCB1, ABCC2, and ABCG2) [see Fig. 2] [61–63]. In addition, active efflux by ABCB1 has been shown to lead to low intracerebral irinotecan concentrations in mice [64]. All metabolites, except SN-38G, are predominately excreted in feces, although they are also detectable in urine [4, 59]. Terminal elimination half-lives (t½) between 5 and 18 h for irinotecan, and between 6 and 32 h for SN-38, were reported [4, 12–14, 59, 65–71]. However, it was later shown that the t½ was initially underestimated as SN-38 concentrations can be detected up to 500 h after infusion [72, 73].

The wide interindividual variability in irinotecan clearance is still not completely understood. Primarily, a decreased clearance in patients with altered hepatic function has been described [12, 13]. Additionally, increasing age may negatively influence irinotecan clearance, although this could not be confirmed in another analysis [13, 74]. Conflicting effects of gender on irinotecan pharmacokinetics have also been proposed. Several studies reported higher irinotecan exposure in women, which, in part, could be explained by decreased SN-38 (metabolic) clearance [13, 59, 75], while others found no gender effect [4, 74, 76]. Several factors such as dose, timing of administration, enzyme activity, and hematocrit levels might be responsible for these differences. In addition, firm conclusions cannot be drawn for weight [13, 77]. Worse clinical performance has been demonstrated to decrease irinotecan clearance [13]. However, interindividual variability does not seem to be related to body size measures such as body surface area (BSA). Although irinotecan dose is generally based on BSA, it has been shown that BSA and other body size measures do not predict irinotecan pharmacokinetics, and that flat-fixed dosing could be a safe alternative [74, 78].

Other Formulations and Administrations

Other Formulations

Furthermore, several other irinotecan formulations have been evaluated. First, oral administration of several different formulations has been investigated and deemed feasible in phase I trials [79–81], but its poor and highly variable bioavailability have limited its current clinical usability [82].

Second, irinotecan drug-eluting beads (DEBIRI) have been developed to control drug release and are mostly used as regional administration. DEBIRI administered into the hepatic artery resulted in higher and prolonged intratumoral irinotecan and SN-38 exposure in liver metastases, whereas systemic exposure was lower than after intravenous administration [83–85]. Hepatic arterial infusion of DEBIRI has been demonstrated to be an effective treatment for unresectable liver metastases [86].

Third, liposomal irinotecan has been developed and is clinically used. Encapsulated into liposomes, irinotecan is stable for a longer period of time, resulting in increased accumulation in tumor tissue and thereby increasing its effect, as described further in Sect. 3.2 [87].

Other Variations in Administration

Irinotecan administration based on circadian timing improved clinical outcome in several clinical trials [88–90], probably due to the circadian rhythm of enzymes and transporters involved in irinotecan pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [91–93]. However, pharmacokinetic consequences have only been investigated in a small randomized study in which an increased metabolic ratio (SN-38/irinotecan AUC) and smaller interindividual variability were found after circadian-timed dosing [94].

Trials on two different—more regional infusion methods—have been conducted. First, locoregional therapy with irinotecan infusion into the hepatic artery has been evaluated for the treatment of unresectable liver metastases; different irinotecan formulations have been demonstrated to be safe and effective [95, 96]. This approach resulted in lower systemic exposure to irinotecan and an increased conversion of irinotecan into SN-38 compared with intravenously administered irinotecan [97]. Second, the use of irinotecan as hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has been investigated as a treatment option for colorectal peritoneal metastases [98–103]. A small fraction of irinotecan is rapidly converted intraperitoneally into SN-38; systemic maximum concentration (Cmax) of SN-38 has been observed 30 min after intraperitoneal administration [98, 100].

Although these different administration methods have been investigated for several years, there is still insufficient evidence that implementing these strategies in daily care could be beneficial.

Drug–Drug Interactions (DDIs)

DDIs with Anticancer Drugs

Many anticancer agents have been investigated in combination with irinotecan, of which no significant pharmacokinetic interactions with irinotecan have been reported for oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin, capecitabine, and monoclonal antibodies [66, 70, 104–123]. In contrast, paclitaxel combined with irinotecan in a 3-weekly regimen caused a significant increase in irinotecan, SN-38, and SN-38G exposure, which was assumed to be caused by competitive inhibition of ABCB1 (Table 1) [124]. Sequencing the administration of paclitaxel after irinotecan seems to improve their synergistic anticancer effects [125], but irinotecan pharmacokinetics are not significantly altered in either sequence [125, 126]. Systemic SN-38 exposure was found to be reduced in patients concomitantly treated with tegafur (S-1) or carboplatin [127–129], of which the latter also reduced irinotecan exposure. Patients seemed to tolerate irinotecan better when thalidomide was coadministered in two phase II studies in which SN-38G exposure was increased at the expense of SN-38 exposure [130]. However, the pharmacokinetic differences could not be replicated [131, 132] and might be caused by confounding as half of the patients also used antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) [130].

Table 1.

Drug–drug interactions with irinotecan

| Drug/OTC/lifestyle | N | Enzyme/transporter | Irinotecan dose | PK alterations | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticancer drugs | ||||||

| Paclitaxel 135–200 mg/m2 D8 |

31 | ABCB1 | 40–60 mg/m2 D1 + 8, Q3W |

Irinotecan SN-38 SN-38G |

AUC24.5 32.7% ↑ AUC24.5 40.4% ↑ AUC24.5 46.2% ↑ |

[124] |

| Thalidomide 400 mg od (for 14D) | 16 | 350 mg/m2,Q3W | SN-38 SN-38G |

AUC48 74% ↓ AUC48 28% ↑ |

[130]a | |

| S-1 (tegafur) 100/120 mg/m2, 4–7D |

4 | ABCG2 | 100–200 mg/m2 Q2 W |

SN-38: | AUC24 50% ↓ | [128] |

| Imatinib 300–600 mg od Cisplatin 30 mg/m2 D1 + 8 |

6 | CYP3A4, CYP3A5 CYP2C9 |

65 mg/m2 D1 + 8, Q3W |

Irinotecan | AUC8 67% ↑, CL 36% ↓ | [134] |

| Lapatinib 1250 mg/day Leucovorin 200 mg/m2 5-FU 600 mg/m2 |

12 | CYP3A4 OATP1B1 ABCB1 ABCG2 |

108 mg/m2 Q2W |

SN-38 | AUC24 41%↑, Cmax 32%↑ | [137] |

| Non-anticancer drugs | ||||||

| Ketoconazole 200 mg od for 2D | 7 | CYP3A4 | 100 mg/m2 (with ketoconazole) 350 mg/m2 (alone) Q3W |

SN-38 APC |

AUC500 109% ↑ AUC500 87% ↓ |

[142] |

| Lopinavir 400 mg/ritonavir 100 mg combination drug (Kaletra) bid | 8 | CYP3A4 UGT1A1 ABCB1 |

150 mg/m2 D1 + 10, Q3W |

Irinotecan SN-38 SN-38G APC |

AUCinf 89% ↑, CL 47% ↓ AUCinf 204% ↑ AUCinf 94% ↑ AUCinf 81% ↓ |

[148] |

| Cyclosporine 5–10 mg/kg | 43 | ABCB1 ABCC2 |

25–75 mg/m2 Q1W | Irinotecan SN-38 |

CL 39–64% ↓ AUC24 23–630% ↑ |

[147] |

| Cyclosporine + Phenobarbital 90 mg for 14D |

39 | ABCB1 ABCC2 UGT1A1 |

72–144 mg/m2 Q1W | Irinotecan SN-38 SN-38G |

AUC24 27% ↓, CL 43% ↑ AUC24 75% ↓ AUC24 50% ↓ |

|

| Celecoxib 400 mg bid | 11 | 50–60 mg/m2 D1 + 8, Q3W |

Irinotecan SN-38 |

CL 18% ↑ AUC12.5 21.8% ↓ |

[151]a | |

| Methimazole | 14 | UGT1A | 660 mg Q3W |

SN-38 SN-38G |

AUC56 14%↑ AUC56 67% ↑ |

[150] |

| Herbal and dietary supplements, and lifestyle | ||||||

| Cigarette smoking | 190 | CYP3A UGT1A1 |

350 mg/m2 or 600 mg fixed dose Q3W |

Irinotecan SN-38 |

AUC100 15% ↓, CL 18% ↑ AUC100 38% ↓ |

[162] |

| St. John’s wort 300 mg tid | 5 | CYP3A4 | 350 mg/m2 Q3W |

SN-38 | AUC24 42% ↓ | [158] |

All PK alterations mentioned are significant at p < 0.05

N sample size, D day, od once daily, bid twice daily, tid three times daily, AUC area under the curve, inf infinity, CL clearance, Q1W every week, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q3W every 3 weeks, PK pharmacokinetics, CYP cytochrome P450, Cmax maximum concentration, 5-FU 5-fluorouracil

aFor thalidomide and celecoxib, conflicting data have been published between pharmacokinetic drug interactions with irinotecan. Studies that did not show a significant drug–drug interaction [131, 132, 152, 153] are illustrated in more detail in the text

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have become very popular in cancer treatment but are also known for their modulating effects on drug-metabolizing enzymes [133]. Several TKIs, i.e. imatinib, pazopanib, sunitinib, lapatinib and gefitinib, have been investigated in combination with irinotecan-containing regimens [134–141]. With the exception of pazopanib and lapatinib, all of these combinations led to excessive toxicity and have therefore not been evaluated further for clinical use. Increased exposure to irinotecan or SN-38 due to the inhibition of CYP3A4, ABCB1, or ABCG2 has been suggested as a cause of the intolerance of irinotecan combined with TKIs, but a pharmacodynamic interaction cannot be ruled out.

DDIs with Non-Anticancer Drugs

Concomitant treatment with non-anticancer drugs such as AEDs, certain antidepressants, antiretroviral drugs, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been shown to affect irinotecan pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics. The combination with the potent CYP3A4 inhibitor ketoconazole was one of the first significant DDIs described for irinotecan (Table 1) [142]. Anecdotally, severe rhabdomyolysis syndrome has been described in a patient using irinotecan and citalopram [143]. Although pharmacokinetic data were not available, competitive metabolism by CYP3A4 was suspected as the underlying mechanism. Hypothetically, other strong CYP3A4-inhibiting antidepressants such as nefazodone could be suspected for an interaction with irinotecan [144].

AEDs are also known for inducing CYP3A, UGTs and CES [145]. The influence of phenytoin, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine on irinotecan pharmacokinetics was evaluated in a population pharmacokinetic model, which suggested that patients using these AEDs should receive a 1.7-fold higher irinotecan dose to reach the same exposure as in patients without AEDs [75]. Individual patients may require an even higher dose, as indicated by a fourfold higher irinotecan clearance and tenfold lower systemic SN-38 exposure in a patient receiving phenytoin [146]. Therefore, the combination of phenytoin and irinotecan must be avoided (if possible), or dosing must be guided on irinotecan pharmacokinetics to ensure a sufficient exposure. In addition, Innocenti et al. found a decreased exposure to SN-38 when irinotecan was combined with cyclosporine and the AED phenobarbital (Table 1) [147].

In addition, an important DDI between irinotecan and the combination treatment with ritonavir and lopinavir, caused by CYP3A4, UGT1A1, and ABC transporter inhibition resulted in a more than twofold increase in SN-38 AUC and a 36% decrease in the SN-38G/SN-38 AUC ratio (Table 1) [148]. A similar effect could be expected of atazanavir, which is also a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 and UGT1A1 [149]. In contrast, by UGT1A induction by methimazole, an increase in SN-38 and SN-38G concentrations, as well as an almost 50% increased ratio of SN-38G/SN-38, was found by within-patient comparison (Table 1) [150].

With regard to frequently used drugs such as NSAIDs and proton pump inhibitors, only a possible DDI with celecoxib and omeprazole has been evaluated to date. One of three studies investigating the coadministration of irinotecan and celecoxib described an increased clearance of irinotecan and a decreased AUC of SN-38, although the mechanism is not clear (Table 1) [151–153]. Although omeprazole influences UGT, CYP3A, ABCB1, and ABCG2, a clinically relevant pharmacokinetic interaction with irinotecan was ruled out in a small crossover study [154].

DDIs with Herbal and Dietary Supplements, and Lifestyle

In general, herbal and dietary supplements are frequently used by cancer patients [155, 156]. Unfortunately, the potential for herb–drug interactions in oncology is not frequently investigated in clinical studies [157]. To date, the effects of St. John’s wort (SJW), milk thistle, cigarette smoking, and cannabis tea on irinotecan pharmacokinetics have been investigated. Concomitant use of SJW resulted in a 42% reduction of SN-38 AUC, primarily caused by CYP3A4 induction (Table 1) [158]. Flavonoids are components of many herbs, such as milk thistle (Silybum marianum), and are able to inhibit CYP3A4, UGT1A1 and ABC transporters [159–161], but an interaction has not yet been demonstrated in clinical trials [161].

Cigarette smoking resulted in a decrease in irinotecan and SN-38 exposure, possibly caused by CYP3A induction (Table 1) [162]. In addition, (medicinal) cannabis can induce CYP3A4 and inhibit ABCB1, and its use is becoming more popular in cancer patients. Although no interaction was demonstrated between irinotecan and medicinal cannabis tea [163], other cannabis formulations contain different concentrations of the enzyme-modulating compounds (e.g. cannabidiol and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol [THC]). Therefore, it remains unclear if cannabinoid oils, the most popular formulation nowadays, are safe in combination with irinotecan.

Pharmacodynamics

Toxicity

Irinotecan is known for its dose-limiting adverse events, primarily diarrhea, neutropenia, and asthenia. Of patients with irinotecan monotherapy, 16–31% experience severe diarrhea, and a comparable percentage of patients suffer from severe neutropenia and severe asthenia, classified as Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) grade 3 or worse [164–168]. Patients treated with a 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) regimen experience severe diarrhea (9–44%) and severe neutropenia (18–54%) to the same extent [168–173]. In addition, neutropenia appears to occur more frequently in females [174]. Although irinotecan dose is lower in this regimen, 5-fluorouracil could also cause these adverse events.

Two types of diarrhea caused by irinotecan can be distinguished: early- and late-onset diarrhea. Early-onset diarrhea starts during, or immediately after, drug infusion and is caused by increased cholinergic activity, which stimulates intestinal contractility and reduces the absorptive capacity of the mucosa [175]. In addition, early-onset diarrhea is often part of an acute cholinergic syndrome with diaphoresis and abdominal pain. The overall incidence of this syndrome is approximately 70% without premedication, and is reduced to 9% by administration of anticholinergic agents (i.e. atropine or hyoscyamine) before irinotecan infusion [176, 177]. Late-onset diarrhea occurs approximately 8–10 days after irinotecan infusion and is characterized by a more severe course, which is probably caused by damage of the intestinal mucosa due to increased oxidative stress by biliary-secreted or intestinally deconjugated SN-38 [76, 178–180]. Several guidelines recommend treating late-onset diarrhea with loperamide or, alternatively, octreotide [181, 182]. Antibiotics have also been used in clinical practice despite sufficient evidence supporting this strategy [182]; however, these interventions are not always sufficient, which could lead to dose reductions, treatment interruptions and hospitalization.

Conflicting results have been reported regarding the relationship between irinotecan and SN-38 exposure and toxicity (Table 2) [60]. An initial study suggested the biliary index (i.e. the ratio of SN-38 to SN-38G AUCs multiplied by the AUC of irinotecan) as a better predictor for gastrointestinal toxicity [178]. Studies on this subject have been contradictory; a higher biliary index was significantly correlated with a higher incidence of severe diarrhea in several studies [76, 178, 183], whereas no significant association was found in other studies (see Table 2) [16, 66, 68, 184]. The duration of neutropenia has been found to be significantly correlated to prolonged systemic SN-38 exposure [73].

Table 2.

Irinotecan toxicity in relation to pharmacokinetics and biliary index

| Study, year | N | Irinotecan dose | Irinotecan | SN-38 | SN-38G | Biliary index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | ||||||

| Ohe et al., 1992 [185] | 36 | 5–40 mg/m2 5D, continuously |

Yes a | No | ND | ND |

| de Forni et al., 1994 [186] | 59 | 50–145 mg/m2 Q1W | Yes a | Yes a | ND | ND |

| Rowinsky et al., 1994 [65] | 32 | 100–345 mg/m2 Q3W | No | No | ND | ND |

| Gupta et al., 1994 [178] | 21 | 100–175 mg/m2 Q1W | No | No | No | Yes b |

| Abigerges et al., 1995 [187] | 64 | 100–750 mg/m2 Q3W | Yes c | Yes c | ND | ND |

| Catimel et al., 1995 [67] | 46 | 33–115 mg/m2 D1–D3, Q3W |

Yes a | No | ND | ND |

| Gupta et al., 1997 [76] | 40 | 145 mg/m2 Q1W | No | No | No | Yes b |

| Canal et al., 1996 [68] | 47 | 350 mg/m2 Q3W | No | No | No | No |

| Mick et al., 1996 [183] | 36 | 145 mg/m2 Q1W | ND | ND | ND | Yes a |

| Rothenberg et al., 1996 [188] | 48 | 125–150 mg/m2 Q1W | No | Yes a | ND | ND |

| Herben et al., 1999 [184] | 29 | 10–12.5 mg/m2 D14–21, continuously | No | No | No | No |

| de Jong et al., 2000 [66] | 52 | 175–300 mg/m2 Q3W | No | No | ND | No |

| Xie et al., 2002 [16] | 109 | 100–350 mg/m2 Q3W | Yes 1 | No | Yes a | No |

| Neutropenia | ||||||

| Ohe et al., 1992 [185] | 36 | 5–40 mg/m2 5D, continuously |

No | Yes d | ND | ND |

| de Forni et al., 1994 [186] | 59 | 50–145 mg/m2 Q1W | Yes e | Yes e | ND | ND |

| Rowinsky et al., 1994 [65] | 32 | 100–345 mg/m2 Q3W | No | Yes e | ND | ND |

| Abigerges et al., 1995 [187] | 64 | 100–750 mg/m2 Q3W | Yes d | Yes d | ND | ND |

| Catimel et al., 1995 [67] | 46 | 33–115 mg/m2 D1–D3, Q3W |

No | No | ND | ND |

| Canal et al., 1996 [68] | 47 | 350 mg/m2 Q3W | Yes e | Yes e | No | No |

| Rothenberg et al., 1996 [188] | 48 | 125–150 mg/m2 Q1W | No | No | ND | ND |

| Herben et al., 1999 [184] | 29 | 10–12.5 mg/m2 D14–21, continuously | No | No | No | No |

| de Jong et al., 2000 [66] | 52 | 175–300 mg/m2 Q3W | No | No | ND | ND |

| Mathijssen et al., 2002 [73] | 26 | 350 mg/m2 Q3W | ND | Yes f | ND | ND |

All assumed relationships mentioned are significant at p < 0.05

N sample size, ND not determined, D day, Q1W every week, Q3W every 3 weeks

aDiarrhea frequency, all grades

bDiarrhea grade ≥ 3

cDiarrhea ≥ 2

dAbsolute decrease in neutrophil count, all grades

ePercentage decrease in neutrophil count, all grades

fEntire time course of absolute neutrophil count decrease

Several interventions to prevent diarrhea have been investigated, such as reducing the intestinal exposure of SN-38. First, in a phase I study, SN-38 excretion in the bile was inhibited by combining irinotecan with cyclosporine (due to ABCC2 and ABCB1 inhibition). Subsequently, phenobarbital (as a UGT1A1 inductor) was added, and the combination of cyclosporine/phenobarbital/irinotecan resulted in a 75% reduction of SN-38 AUC [147]. However, when studied in a large, randomized, phase III trial, the combination of cyclosporine, irinotecan and panitumumab did not significantly reduce the incidence of severe diarrhea [189]. In another randomized trial, prophylactic use of racecadotril, an antisecretory drug, also failed to reduce this adverse event [190]. Alternatively, SN-38 can be bound to activated charcoal or calcium aluminosilicate clay in the intestine. Until now, only the activated charcoal has been found to reduce the incidence of diarrhea [191, 192]; however, evidence from a phase III study and additional pharmacokinetic analysis is warranted to understand the real effect of activated charcoal, which also exhibits a general antidiarrhoeic effect, and therefore the use of charcoal is not common practice.

Another attempt to reduce toxicity was by inhibition of β-glucuronidase production by antibiotics (i.e. streptomycin, penicillin, and neomycin), amopaxine, and herbal medicines, all without a relevant reduction in diarrhea incidence [56–58, 193]. However, when combined with cholestyramine to reduce reabsorption, β-glucuronidase inhibition by levofloxacin was found to reduce irinotecan-induced diarrhea [194]. In addition, a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed a 20% reduction in diarrhea incidence when irinotecan was combined with probiotics. Unfortunately, this did not result in a significant difference between groups, probably due to a lack of statistical power [195]. Lastly, altering the intestinal environment by alkalinization or reduction of inflammation (by the use of budesonide) did also not reduce intestinal toxicity [196–201].

Currently, fasting before chemotherapy is investigated to reduce toxicity, which has been shown to be effective in mice without affecting the anticancer effects. Systemic and hepatic exposure to SN-38 was reduced in these mice, but intratumoral concentrations were unaltered [202, 203]. A prospective trial is currently ongoing in order to assess the effects of fasting in irinotecan-treated patients and to elucidate the underlying biological mechanisms (http://www.trialregister.nl/; trial ID: NTR5731).

Efficacy

Irinotecan is effective in a wide range of malignancies. In metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), irinotecan has its most prominent role as monotherapy or within combination therapy. As first-line mCRC treatment, the FOLFIRI regimen proved to be superior to 5-fluorouracil with leucovorin and to irinotecan monotherapy; a response rate (RR) of 39% and median overall survival (OS) of 14.8–17.4 months has been reported [168, 169]; however, the addition of oxaliplatin to this regimen (i.e. FOLFOXIRI) substantially increased treatment efficacy, as shown by an RR of 60% and median OS of approximately 23 months [204, 205]. As second-line treatment after 5-fluorouracil-containing regimens, irinotecan leads to a significantly longer OS than 5-fluorouracil with leucovorin or best supportive care (BSC) [166, 167]. For patients with a KRAS wild-type tumor, efficacy of palliative treatment could be increased by combining irinotecan monotherapy, FOLFIRI, or FOLFOXIRI with monoclonal antibodies (e.g. bevacizumab, cetuximab, panitumumab, ramucirumab) [165, 170–172, 206, 207]. In the adjuvant setting, the addition of irinotecan to 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin did not result in a survival benefit [208, 209]. Patients with tumors characterized by high microsatellite instability (MSI) have been suggested to respond better to irinotecan-based chemotherapy, [210, 211] but a recent meta-analysis failed to show any predictive value of MSI status in relation to treatment response [212].

For advanced esophageal or junction tumors, irinotecan has proven to be effective as monotherapy and when combined with cisplatin, mitomycin, capecitabine and oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin and docetaxel [213–219]; however, of these regimens, only irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil was evaluated in a phase III trial in which this combination was inferior to cisplatin/5-fluorouracil [220]. In advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative gastric cancer, the addition of irinotecan to different combination therapies gave an OS benefit in a pooled analysis of ten studies—median OS was 11.3 months and RR was approximately 38% [221].

Irinotecan is also used in the treatment of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-SCLC (NSCLC). For advanced NSCLC, irinotecan combined with taxanes, platinum, ifosfamide, or gemcitabine demonstrated efficacy as first-line treatment in several trials [222]. For advanced SCLC, irinotecan combined with cisplatin or carboplatin had similar RR and median OS as platinum compounds with etoposide (RR 39–84% and median OS 9–13 months) and is therefore used as first-line treatment in Japan, whereas the etoposide-containing regimen is preferred elsewhere [223]. Furthermore, irinotecan has demonstrated anticancer activity in phase II trials in a wide range of other solid tumors (i.e. mesothelioma, glioblastoma, gynecological cancers, and head and neck cancer), although no phase III data are available [224–231].

Finally, in pancreatic cancer, the combination of 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) is used for both first-line adjuvant and palliative treatment in which it was shown to be superior to gemcitabine monotherapy (median OS 11.1 months, RR 31.6%) [232]. Liposomal irinotecan has recently been approved as second-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer for patients with progression on gemcitabine-based therapies [87]. Efficacy of this liposomal formulation needs to be explored further in other tumor types.

Pharmacogenetics

Expression and functionality of enzymes and drug transporters involved in the metabolism and elimination of irinotecan can be affected by genetic polymorphisms that could influence both irinotecan pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. This section provides an overview of clinical correlations between polymorphisms and irinotecan pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

Associations between UGT1A1 Polymorphisms and Irinotecan Pharmacodynamics

With more than 100 reported genetic variants [233], UGT1A1 is a highly polymorphic enzyme. The most frequently studied UGT1A1 polymorphisms in relation to irinotecan pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are UGT1A1*6 and UGT1A1*28. The majority of the genetic association studies have focused on neutropenia and diarrhea as clinical endpoints [169].

Wild-type UGT1A1 is characterized by six thymine adenine (TA) repeats in the promotor region, whereas UGT1A1*28 (rs8175347) carriers have an extra TA repeat that impairs UGT1A1 transcription and thereby reduces expression by approximately 70% [234]. The incidence of this genetic variant is relatively high among Caucasians (minor allele frequency [MAF] 26–39%) and Africans/African Americans (MAF 30–56%) [235, 236]. Among the Asian population, UGT1A1*28 is far less common, as indicated by an MAF of 9–20% [235, 236]. With a reported MAF of up to 47%, another polymorphism—UGT1A1*6 (rs4148323, 211G > A)—is more common in Asian populations and may therefore be a better predictor for irinotecan-related toxicities in that area of the world [237]. UGT1A1*6 also results in an approximately 70% reduction of UGT1A1 activity in individuals carrying the UGT1A1*6/*6 genotype [238].

Both UGT1A1*6 and *28 polymorphisms result in an increased systemic exposure to irinotecan and SN-38 in patients homozygous for these variants, thereby increasing the risk of irinotecan-associated adverse events [239, 240]. This is also accompanied by increased financial costs of toxicity management [241]. Due to the high number of genetic association studies on the clinical effects of UGT1A1*6 and *28 on irinotecan pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and large differences between studies in terms of tumor type, dosing regimen, and genetic models, this review will mainly focus on meta-analyses for UGT1A1*28 and *6 to extract the most relevant information with the highest level of evidence (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of pharmacogenetic studies on irinotecan toxicity and survival

| Polymorphism | Ethnicity | Endpoint | Dose range (mg/m2) | Main findings | No. of patients | No. of studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analyses | |||||||

| UGT1A1*28/*28 (rs8175347) vs. *1/*28 or *1/*1 | Not reported | Hematologic toxicities | 80–125 | OR 1.80, 95% CI 0.37–8.84, p = 0.41 | 229 | 3 | [242] |

| 180 | OR 3.22, 95% CI 1.52–6.81, p = 0.008 | 410 | 4 | ||||

| 200–350 | OR 27.8, 95% CI 4.0–195, p = 0.005 | 184 | 3 | ||||

| *28/*28 vs. *1/*1 | Mainly Caucasian | Neutropenia | < 150 | OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.34–4.39, p = 0.003 | 300 | 4 | [243] |

| 150–250 | OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.62–2.47, p < 0.001 | 1481 | 9 | ||||

| ≥ 250 | OR 7.22, 95% CI 3.10–16.78, p < 0.001 | 217 | 3 | ||||

| *28/*28 vs. *1/*28 or *1/*1 | Caucasian | Neutropenia | 80–350 | OR 3.44, 95% CI 2.45–4.82, p < 0.00001 | 2015 | 14 | [244] |

| *28/*28 vs. *1/*28 or *1/*1 | Diarrhea | > 150 | OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.23–3.38, p = 0.006 | 1317 | 8 | ||

| < 150 | OR 1.41, 95% CI 0.82–2.43, p = 0.21 | 663 | 6 | ||||

| *1/*28 or *28/*28 vs. *1/*1 | Asian | Neutropenia | 50–100 | OR 1.47, 95% CI 0.90–2.42, p = 0.13 | 515 | 8 | [245] |

| *6/*6 (rs4148323) vs. *1/*6 or *1/*1 | Diarrhea | OR 4.90, 95% CI 2.02–11.88, p = 0.0004 | 225 | 4 | |||

| *6/*6 vs. *1/*6 or *1/*1 | Tumor response | OR 1.51, 95% CI 0.78–2.92, p = 0.22 | 225 | 4 | |||

| *28/*28 or *1/*28 vs. *1/*1 | OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.59–1.82, p = 0.91 | 390 | 7 | ||||

| *28/*28 vs. | Asian | Neutropenia | 60–200 | OR 1.67, 95% CI 0.94–2.97 | 658 | 6 | [246] |

| *6/*28 | 30–350 | OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.82–3.58 | 886 | 13 | |||

| *6/*6 or *28/*28 or *6/*28 vs. *1/*6 or *1/*28 or *1/*1 | Asian | Neutropenia | 60–350 | OR 3.275, 95% CI 2.152–4.983, p = 0.000 | 923 | 11 | [247] |

| *1/*6 or *6/*6 vs. *1/*1 | OR 1.542, 95% CI 1.180–2.041, p = 0.001 | 994 | 9 | ||||

| *6/*6 vs. *1/*1 | Asian | Neutropenia | 30–375 | OR 4.44, 95% CI 2.42–8.14, p < 0.001 | 833 | 7 | [248] |

| *28/*28 or *1/*28 vs. *1/*1 | Asian | Diarrhea | > 125 | OR 3.02, 95% CI 1.42–6.44, p = 0.004 | 309 | 4 | [249] |

| *28/*28 or *1/*28 vs. *1/*1 | Caucasian | OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.38–2.70, p < 0.001 | 1096 | 11 | |||

|

*28/*28 vs. *1/*1 *1/*28 vs. *1/*1 |

Caucasian | OS and PFS | 60–350 | All comparisons not significant for both OS and PFS (p > 0.05) | 1524 (OS) 1494 (PFS) |

10 | [251] |

| Clinical studies | |||||||

| UGT1A1*60 | Asian | PK, tumor response, grade 4 neutropenia, grade 3 diarrhea, delivered dose | 80 | p > 0.05 for all endpoints | 81 | 1 | [253] |

| UGT1A1*60 | Not specified (probably Korean) | Neutropenia, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain | 150 | p > 0.05 for all endpoints | 42 | 1 | [254] |

| UGT1A1*28, *60, *93 (rs10929302) | Caucasian (50 pts), Black (10 pts), Hispanic (4 pts), Pacific Islander (1 pt), Asian (1 pt) | Neutropenia | 350 |

UGT1A1 haplotype (

*28/*60/*93

) associated with grade 4 neutropenia,

p < 0.001 |

66 | 1 | [255] |

| UGT1A1*28, *93, ABCB1 (rs1045642) | Not specified, presumably Caucasian (France) | Hematologic toxicities | 180 | UGT1A1*28/*28 and *93/*93: increased risk of hematologic toxicity (p = 0.01) | 184 | 1 | [258] |

| UGT1A1*93, ABCB1 (rs12720066), ABCC1 (rs6498588, rs17501331) | Caucasian (67 pts), African American (11 pts) | ANC nadir, SN-38 AUC | 300 or 350 |

Increased SN-38 AUC:

UGT1A1*93, ABCC1

(rs6498588)

Decreased SN-38 AUC: ABCB1 (rs12720066) Increased ANC nadir: ABCB1 (rs12720066) Decreased ANC nadir: UGT1A1*93, ABCC1 (rs17501331) |

78 | 1 | [256] |

| UGT1A1*28 and *93 | Caucasian (94 pts), Asian (2 pts) | Diarrhea | 40–80, 180, 350 | UGT1A1*28/*28 and *93/*93 associated with grade 3/4 diarrhea (p < 0.05) | 96 | 1 | [260] |

| Neutropenia | No significant effect on neutropenia | ||||||

|

UGT1A1:*28,*93 UGT1A6: rs2070959 UGT1A9: *22 (rs45625337), −688A/C variant UGT1A7*3 3′UTR: 440C > G variant |

Not specified, presumably Caucasian (Canada) | Neutropenia | 180 |

UGT1A1*93

associated with neutropenia.

Haplotype (UGT1A1*28, *60, *93, UGT1A7*3, UGT1A9*1) associated with grade 3–4 neutropenia: OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.35–4.39, p = 0.004 Haplotypes ‘II’ and ‘III’ (variants in UGT1A9, 1A7, 1A6, and 3′UTR wild-type) associated with grade 3–4 neutropenia: OR 2.15 and 5.28, respectively |

167 | 1 | [259] |

| Among other genes: UGT1A1*28, *93 | Caucasian (450 pts), African American (36 pts), Hispanic (16 pts), Asian (9 pts), other (9 pts) | (Febrile) neutropenia, vomiting |

125 or 200 | UGT1A1*93 associated with grade 3 febrile neutropenia, grade 4 neutropenia (p < 0.001), and grade 3 vomiting (p = 0.004) | 520 | 1 | [261] |

|

UGT1A1:*6, *28 UGT1A7*3 UGT1A9*1 |

Asian | Adverse events, therapeutic intervention | 60, 70, 100 or 180 | UGT1A1*6/*28, UGT1A7*3/*3 or UGT1A9*1/*1: greater risk of adverse events and therapeutic intervention: OR 11.00, 95% CI 1.633–74.083, p = 0.014 | 45 | 1 | [263] |

| UGT1A1*28, UGT1A1*60, UGT1A1*93, UGT1A7*3, and UGT1A9*22 | Caucasian | Hematologic toxicity, response rate | 180 | Haplotype II (all variants except UGT1A1*22) associated with increased response rate: OR 8.61, 95% CI 1.75–42.38, p = 0.01 | 250 | 1 | [262] |

| Among other genes: SLCO1B1 (rs4149056) UGT1A1*6 UGT1A9*22 ABCC2 (rs3740066) ABCG2 (rs2231137) |

Asian | Neutropenia | 65 or 80 | SLCO1B1 and UGT1A1*6 : increased risk for grade 4 neutropenia | 107 | 1 | [264] |

| Diarrhea | UGT1A9*1/*1, ABCC2 (rs3740066), ABCG2 (rs2231137) : increased risk for grade 3 diarrhea | ||||||

| Among other genes: UGT1A1*93, ABCC1 (rs3765129), SLCO1B1*1b (rs2306283) |

African American (11 pts), Caucasian (67 pts), other (7 pts) | ANC nadir | 300, 350 |

UGT1A1*93, ABCC1 (rs3765129):

decreased ANC nadir SLCO1B1*1b (rs2306283): increased ANC nadir (p < 0.05) |

85 | 1 | [174] |

| Among other genes: ABCB1 (rs1045642, rs1128503, rs2032582), | Caucasian | Toxicity | 180 | ABCB1 (rs1045642) associated with early toxicity: OR 3.79 95% CI 1.09–13.2 | 140 | 1 | [268] |

| Response rate | ABCB1 haplotype ( rs 1045642, rs1128503, rs2032582): shorter OS, OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.01–2.45 | ||||||

| ABCC2: rs1885301, rs2804402, rs717620, rs2273697, rs17216177, rs3740066 | Caucasian | Diarrhea | 260–875 mg | Decreased incidence of diarrhea for ABCC2*2 haplotype (rs1885301, rs2804402, rs717620, rs2273697, rs17216177, rs3740066) without UGT1A1*28 allele: OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.04–0.61), p = 0.005 | 167 | 1 | [271] |

| Among other genes: ABCC5 (rs10937158, rs3749438, rs2292997) ABCG1 (rs225440) |

Caucasian | Diarrhea | 180 |

Reduced risk of diarrhea for

ABCC5

haplotype (rs10937158 and rs3749438):

OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.23–0.67, p = 0.0006 |

167 | 1 | [272] |

| Neutropenia | Increased risk of neutropenia for co-occurrence of ABCG1 and ABCC5 (rs2292997): OR 5.93 95% CI 2.25–15.59, p = 0.0002 | ||||||

| SLCO1B1*1b | Caucasian | Neutropenia | 300, 350, 380–600 (mg) | SLCO1B1*1b: increased ANC nadir (p < 0.05) | 67 (discovery cohort), 108 (replication cohort) | 1 | [273] |

| Among other genes: SLCO1B1*1b, SLCO1B1*5 (rs4149056) | Caucasian | SN-38 PK, toxicity, PFS | 180 |

SLCO1B1*1b: increased PFS (p < 0.05). SLCO1B1*5: increased SN-38 plasma concentration and increased risk of neutropenia (combined with UGT1A1*28) (p < 0.05) |

127 | 1 | [274] |

Significant findings are shown in bold

CI confidence interval, ANC absolute neutrophil count, AUC area under the plasma concentration–time curve, OR odds ratio, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, PK pharmacokinetics, pt(s) patient(s)

Initially, significant associations between UGT1A1*28 and hematologic toxicities were only reported for irinotecan doses higher than 180 mg/m2 [242]. However, more recent meta-analyses did not show a dose-dependent effect of UGT1A1*28. In addition, *28 carriers receiving lower irinotecan doses were at risk of neutropenia [243, 244]. These meta-analyses were carried out in a predominantly Caucasian population, thus regardless of scheduled starting dose, genotyping for UGT1A1*28 and dose reductions in all Caucasian patients homozygous for UGT1A1*28 may be considered to reduce the risk of severe neutropenia.

Presumably due to the lower incidence of UGT1A1*28 in the Asian population, the effects of UGT1A1*28 on toxicity endpoints are less straightforward in this population. Several meta-analyses in Asian patients with different tumor types and treatment schedules did not show any significant association between UGT1A1*28 and irinotecan-induced neutropenia [245, 246]. In contrast, UGT1A1*6 seems to be a more accurate predictor of irinotecan-induced toxicity; Asian patients with gastrointestinal tumors or NSCLC were more likely to suffer from neutropenia if they were carrying at least one UGT1A1*6 allele (Table 3) [245, 247]. This association does not seem to be dose-dependent [248].

Both Caucasian and Asian patients homozygous or heterozygous for UGT1A1*28 have a greater risk of suffering from severe diarrhea compared with wild-type patients after receiving irinotecan doses > 125 mg/m2 [249]. In another meta-analysis among Caucasian *28/*28 carriers, this dose-dependent effect was also observed [244]. In Asian patients, UGT1A1*6 not only correlates well with the risk for irinotecan-induced neutropenia but is also significantly associated with severe diarrhea [245, 248]. Whether this association is dose-dependent is currently unknown since no dose subgroup analysis has been carried out [250].

It seems that response or survival endpoints are not significantly affected by UGT1A1*6 or *28. Both UGT1A1*6 and UGT1A1*28 genotypes did not have any significant association with tumor response in Asian NSCLC or SCLC patients receiving irinotecan as first- or second-line chemotherapy [245]. Furthermore, the presence of one or more UGT1A1*28 alleles in Caucasian patients with colorectal cancer did not significantly affect overall and progression-free survival (PFS) [251].

Besides UGT1A1*6 and UGT1A1*28, other common UGT1A1 polymorphisms could theoretically also affect irinotecan-related toxicity (Table 3). For instance, UGT1A1*60 (rs4124874; 3279T > G) is in linkage with UGT1A1*28 and is associated with a decrease in transcriptional activity [238]. This genetic variant is common among Caucasians (MAF 47%) and African Americans (MAF 85%) [252]. Two clinical studies did not report any significant associations between UGT1A1*60 status and irinotecan-related toxicities [253, 254], irinotecan pharmacokinetics, or tumor response [253]. The only significant association including UGT1A1*60 was found in a haplotype analysis in which a haplotype consisting of UGT1A1*28, *93 and *60 variant alleles was significantly associated with grade 4 neutropenia [255].

Similar to UGT1A1*60, UGT1A1*93 (rs10929302; − 3156G> A) is also in linkage disequilibrium with UGT1A1*28 [252]. UGT1A1*93 results in reduced UGT1A1 expression and is associated with elevated bilirubin concentrations in patients homozygous for UGT1A1*93 [255]. With an MAF of approximately 30%, this genetic variant is commonly detected in Caucasians and African Americans [252]. Clinically, UGT1A1*93 is associated with increased SN-38 AUC [256], lower neutrophil count [257], increased incidence of hematologic toxicities (including neutropenia) [258, 259], diarrhea [260], and grade 3 vomiting [261]. Moreover, UGT1A1*93 was also part of a haplotype including variant alleles of UGT1A1*28, *60, *93, and UGT1A7*3, which was associated with increased RR [262]. A prospective trial on genotype-guided irinotecan dosing based on UGT1A1*28 and UGT1A1*93 genotype status is currently ongoing (trial ID: NTR6612).

Associations between Other UGT1A Polymorphisms and Irinotecan Pharmacodynamics: UGT1A7 and UGT1A9

Compared with patients with UGT1A9*1/*1, individuals carrying the UGT1A9*22 genotype (T9 > T10; MAF 45%) show higher enzyme expression and higher SN-38 glucuronidation and are therefore more at risk for diarrhea [263, 264]. Other UGT1A9 variants, UGT1A9*3 (98T> C; MAF 3%) and UGT1A9*5 (766G> A; MAF 1%), are rare in Caucasians and are therefore not likely to significantly affect irinotecan pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in this population [265]. Lower enzyme activity and SN-38 conjugation is observed in UGT1A7*3 [263] and UGT1A7*4 polymorphisms [266]. In line with these findings, UGT1A7*3/*3 carriers are at greater risk of adverse events while receiving irinotecan chemotherapy [262, 263]. A haplotype consisting of UGT1A7*3, UGT1A9*1, UGT1A1*28, UGT1A1*60, and UGT1A1*93 alleles was associated with severe neutropenia in a cohort of 167 colorectal cancer patients treated with FOLFIRI [259]. In the same cohort, UGT1A7*3 was also part of two other haplotypes, including UGT1A9, UGT1A7, and UGT1A6 variants, associated with an increased risk of grade 3–4 neutropenia (Table 3).

Associations between Drug Transporter Polymorphisms and Irinotecan Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics

Since both irinotecan and SN-38 are substrates of ABC transporters (Fig. 2), ABC polymorphisms may also affect irinotecan pharmacokinetics [267], as well as irinotecan-related toxicities [174]. In a multivariate analysis including UGT1A1*93, and ABCC1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs6498588 and rs17501331, these variants were associated with increased SN-38 plasma concentrations and/or decreased absolute neutrophil counts [256]. The opposite effects were reported for the ABCB1 variant rs12720066, which was associated with decreased SN-38 exposure and increased neutrophils. Carriers of another ABCB1 SNP (rs1045642) had an increased risk for early toxicity and lower treatment response [268]. In patients with liver metastases treated with hepatic artery infusion of irinotecan, oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil and intravenous cetuximab, this SNP was also associated with toxicity (grade 3–4 neutropenia), increased systemic concentrations of oxaliplatin and cetuximab, and prolonged PFS [269]. Furthermore, carriers of the ABCB1 haplotype (including rs1045642, rs1128503, rs2032582) responded less frequently and had shorter survival [268]. In addition to ABCB1 and ABCC1, polymorphisms of ABCC2 (rs3740066) and ABCG2 (rs2231137) were reported to be independently predictive for toxicity (i.e. grade 3 diarrhea) [264]. In contrast, the ABCG2 42 1C>A A NP seems to have a limited impact on irinotecan exposure [270]. Polymorphisms in the gene for the hepatic efflux transporter ABCC2 may have a protective effect on diarrhea, which is presumably caused by decreased hepatobiliary transport of irinotecan and therefore reduced irinotecan exposure to the gut [271]. This protective effect was observed in Caucasian patients with the ABCC2*2 haplotype (including six ABCC2 variants without any UGT1A1*28 alleles). Although their role in irinotecan efflux has not yet been established, ABCC5 and ABCG1 could also be involved in this process since several SNPs in these transporters are correlated with severe diarrhea [272].

OATP1B1, encoded by the SLCO1B1 gene, is involved in the hepatic uptake of SN-38 (Fig. 2). In Caucasian patients carrying at least one SLCO1B1*1b variant allele (rs2306283; MAF 38%), median neutrophil count increased approximately twofold compared with wild-types [273], presumably by increased hepatic uptake of SN-38, thereby reducing SN-38 plasma concentrations (Table 3). This result confirms an earlier genetic association study on the effects of drug transporters on irinotecan neutropenia and pharmacokinetics [174]. In addition, SLCO1B1*1b was also associated with increased PFS in patients with colorectal and pancreatic cancer [274]. Thus, SLCO1B1*1b could potentially be a protective biomarker for neutropenia and may improve efficacy. In contrast, SLCO1B1*5 (rs4149056) leads to reduced transporter activity and was associated with increased SN-38 plasma concentrations and an increased risk of neutropenia (in combination with UGT1A1*28 variant alleles) [274].

Implementation of Genotype-Adjusted Irinotecan Dosing Guidelines

Both the US FDA and Health Canada/Santé Canada (HCSC) recommend a reduction of the irinotecan starting dose in patients who are homozygous for UGT1A1*28 [275, 276] without specifying the extent of reduction (Table 4). In contrast, the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group did not find sufficient evidence that UGT1A1 genotyping should be used [277]. However, subsequent guidelines underline the importance of UGT1A1 genotyping, especially for UGT1A1*28 variant alleles in Western countries. For example, in France and The Netherlands, a reduction of the starting dose of 25–30% is recommended in patients homozygous for UGT1A1*28 receiving higher doses of irinotecan (≥ 180 mg/m2) [278, 279]. Regarding liposomal irinotecan, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommends an initial dose reduction from 80 to 60 mg/m2 in patients homozygous for UGT1A1*28 [280]. In line with the significant associations between UGT1A1*6 genotype and irinotecan-induced toxicities in Asian populations, the Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) recommends screening patients for UGT1A1*6 and *28 polymorphisms [281].

Table 4.

Overview of guidelines on pharmacogenetic testing for irinotecan

| Organization | Country | Year of last update | Genotype recommended for testing | Dose reduction explicitly recommended? | Recommendation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US FDA | USA | 2014 | UGT1A1*28 | Yes | UGT1A1*28/*28: starting dose reduction by at least one dose level | [275] |

| Health Canada/Santé Canada (HCSC) | Canada | 2014 | UGT1A1*28 | Yes | UGT1A1*28/*28: reduced starting dose | [276] |

| National Pharmacogenetics Network (RNPGx) and the Group of Clinical Onco-pharmacology (GPCO-Unicancer) | France | 2015 | UGT1A1*28 | Yes |

UGT1A1*28/*28 and dose 180–230 mg/m2: 25–30% reduction of starting dose UGT1A1*28/*28 and dose ≥ 240 mg/m2: irinotecan contraindicated |

[278] |

| Royal Dutch Association for the Advancement of Pharmacy (KNMP) | The Netherlands | 2011 | UGT1A1*28 | Yes |

UGT1A1*28/*28 and dose > 250 mg/m2: 30% reduction of starting dose |

[279] |

| European Medicines Agency (EMA) | Europe | 2017 | UGT1A1*28 | Yes | UGT1A1*28/*28: reduce starting dose of liposomal irinotecan from 80 to 60 mg/m2 | [280] |

| Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) | Japan | 2014 | UGT1A1*6 and *28 | No | Use irinotecan with caution in patients with the following genotypes: UGT1A1*6/*6, UGT1A1*28/*28 and UGT1A1*6/*28 | [281] |

Despite the establishment of these guidelines, UGT1A1 genotyping is currently not routinely performed [282], which could be explained by the fact that prospective studies evaluating the clinical effects of genotype-directed dosing are scarce. Most likely, reduction of the irinotecan dose to prevent toxicity in carriers of UGT1A1*1/*28 and UGT1A1*28/*28 is indeed useful since the maximum tolerated dose of irinotecan was lower in these patients relative to wild-type patients [283]. Whether a dose reduction of irinotecan affects tumor response in UGT1A1*28 carriers is yet unknown. On the other hand, patients with the UGT1A1*1/*1 or UGT1A1*1/*28 genotype may tolerate higher irinotecan doses than the currently recommended doses and are therefore at risk of suboptimal treatment. Indeed, a phase I dose-finding study convincingly showed that, compared with the recommended irinotecan dose of 180 mg/m2 in the FOLFIRI regimen, substantial higher doses of irinotecan (up to 420 mg/m2) were tolerated in patients wild-type or heterozygous for UGT1A1*28 [284]. More recently, similar findings were observed in patients receiving FOLFIRI in combination with bevacizumab [282], implying that the therapeutic window of irinotecan may be increased for the UGT1A1*1/*1 and UGT1A1*1/*28 genotypes.

In summary, particularly for Caucasians, UGT1A1*28 seems to be a good predictor for neutropenia (all irinotecan doses) and diarrhea (doses > 125 mg/m2). UGT1A1*28 is also significantly associated with an increased risk for diarrhea in Asian patients at irinotecan doses > 125 mg/m2. However, in Asian populations the UGT1A1*6 variant is more common and appears to be a more accurate predictor for neutropenia (all irinotecan doses) and diarrhea. In addition to UGT1A1*6 and UGT1A1*28, UGT1A1*93 is also significantly associated with irinotecan-induced toxicity. Less extensively studied polymorphisms such as UGT1A7*3 and UGT1A9*1, and drug transporter polymorphisms (ABCB1, ABCC5, ABCC2, ABCG1, SLCO1B1), may also be useful predictors for toxicity. Interestingly, CYP3A4*22 has not been studied thus far, while this SNP has shown relevance for many other CYP3A substrates [285–287]. In order to determine the true value of genotype-driven dosing of irinotecan, the efficacy of this dosing strategy should be evaluated prospectively. The inclusion of additional predictive genetic variants (e.g. UGT1A1*6, *93) in genotype-directed dosing schedules may improve their predictive value.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Irinotecan is a crucial anticancer drug in treatment regimens for several solid tumors. Many factors that contributed to the large interindividual pharmacokinetic variability have been elucidated. In the last decade, much progress has been made in unraveling the pharmacogenetic influence on systemic exposure, toxicity, and survival, however this knowledge has not yet been sufficiently translated into general clinical practice.

Based on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacogenetic data discussed in this review, we recommend dosing adjustments in the following situations:

Concomitant use of potent CYP3A4 inducers (e.g. rifampicin, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, SJW): avoid combination.

Concomitant use of potent CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g. ketoconazole, itraconazole): avoid combination.

Caucasians: perform genotyping for UGT1A1*28. Consider at least a 25% reduction of starting dose in patients homozygous for UGT1A1*28.

Asians: perform genotyping for UGT1A1*6. Consider dose reduction of the starting dose in patients homozygous for UGT1A1*6. Exact dosing adjustments are as yet unknown.

Future research should prospectively investigate the added value of individualized irinotecan treatment based on patient characteristics, pharmacogenetics, and comedication. Furthermore, novel drug formulations such as liposomal forms of irinotecan could help to pharmacologically optimize irinotecan treatment.

Funding

This work was not supported by external funding.

Conflicts of interest

Femke M. de Man, Andrew K.L. Goey, Ron H.N. van Schaik, Ron H.J. Mathijssen, and Sander Bins declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hsiang YH, Liu LF. Identification of mammalian DNA topoisomerase I as an intracellular target of the anticancer drug camptothecin. Cancer Res. 1988;48(7):1722–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shao RG, Cao CX, Zhang H, Kohn KW, Wold MS, Pommier Y. Replication-mediated DNA damage by camptothecin induces phosphorylation of RPA by DNA-dependent protein kinase and dissociates RPA:DNA-PK complexes. EMBO J. 1999;18(5):1397–1406. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rivory LP, Robert J. Molecular, cellular, and clinical aspects of the pharmacology of 20(S)camptothecin and its derivatives. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;68(2):269–296. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)02009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie R, Mathijssen RH, Sparreboom A, Verweij J, Karlsson MO. Clinical pharmacokinetics of irinotecan and its metabolites: a population analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(15):3293–3301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fassberg J, Stella VJ. A kinetic and mechanistic study of the hydrolysis of camptothecin and some analogues. J Pharm Sci. 1992;81(7):676–684. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600810718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hertzberg RP, Caranfa MJ, Holden KG, Jakas DR, Gallagher G, Mattern MR, et al. Modification of the hydroxy lactone ring of camptothecin: inhibition of mammalian topoisomerase I and biological activity. J Med Chem. 1989;32(3):715–720. doi: 10.1021/jm00123a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivory LP, Chatelut E, Canal P, Mathieu-Boue A, Robert J. Kinetics of the in vivo interconversion of the carboxylate and lactone forms of irinotecan (CPT-11) and of its metabolite SN-38 in patients. Cancer Res. 1994;54(24):6330–6333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasaki Y, Yoshida Y, Sudoh K, Hakusui H, Fujii H, Ohtsu T, et al. Pharmacological correlation between total drug concentration and lactones of CPT-11 and SN-38 in patients treated with CPT-11. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995;86(1):111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb02995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haaz MC, Rivory LP, Riche C, Robert J. The transformation of irinotecan (CPT-11) to its active metabolite SN-38 by human liver microsomes. Differential hydrolysis for the lactone and carboxylate forms. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;356(2):257–262. doi: 10.1007/pl00005049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke TG, Mi Z. The structural basis of camptothecin interactions with human serum albumin: impact on drug stability. J Med Chem. 1994;37(1):40–46. doi: 10.1021/jm00027a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Combes O, Barre J, Duche JC, Vernillet L, Archimbaud Y, Marietta MP, et al. In vitro binding and partitioning of irinotecan (CPT-11) and its metabolite, SN-38, in human blood. Invest New Drugs. 2000;18(1):1–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1006379730137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chabot GG, Abigerges D, Catimel G, Culine S, de Forni M, Extra JM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of irinotecan (CPT-11) and active metabolite SN-38 during phase I trials. Ann Oncol. 1995;6(2):141–151. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein CE, Gupta E, Reid JM, Atherton PJ, Sloan JA, Pitot HC, et al. Population pharmacokinetic model for irinotecan and two of its metabolites, SN-38 and SN-38 glucuronide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72(6):638–647. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.129502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poujol S, Pinguet F, Ychou M, Abderrahim AG, Duffour J, Bressolle FM. A limited sampling strategy to estimate the pharmacokinetic parameters of irinotecan and its active metabolite, SN-38, in patients with metastatic digestive cancer receiving the FOLFIRI regimen. Oncol Rep. 2007;18(6):1613–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Younis IR, Malone S, Friedman HS, Schaaf LJ, Petros WP. Enterohepatic recirculation model of irinotecan (CPT-11) and metabolite pharmacokinetics in patients with glioma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63(3):517–524. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie R, Mathijssen RH, Sparreboom A, Verweij J, Karlsson MO. Clinical pharmacokinetics of irinotecan and its metabolites in relation with diarrhea. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72(3):265–275. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.126741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loos WJ, Verweij J, Gelderblom HJ, de Jonge MJ, Brouwer E, Dallaire BK, et al. Role of erythrocytes and serum proteins in the kinetic profile of total 9-amino-20(S)-camptothecin in humans. Anticancer Drugs. 1999;10(8):705–710. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199909000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slatter JG, Su P, Sams JP, Schaaf LJ, Wienkers LC. Bioactivation of the anticancer agent CPT-11 to SN-38 by human hepatic microsomal carboxylesterases and the in vitro assessment of potential drug interactions. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25(10):1157–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morton CL, Wadkins RM, Danks MK, Potter PM. The anticancer prodrug CPT-11 is a potent inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase but is rapidly catalyzed to SN-38 by butyrylcholinesterase. Cancer Res. 1999;59(7):1458–1463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudakova EV, Boltneva NP, Makhaeva GF. Comparative analysis of esterase activities of human, mouse, and rat blood. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2011;152(1):73–75. doi: 10.1007/s10517-011-1457-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humerickhouse R, Lohrbach K, Li L, Bosron WF, Dolan ME. Characterization of CPT-11 hydrolysis by human liver carboxylesterase isoforms hCE-1 and hCE-2. Cancer Res. 2000;60(5):1189–1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bencharit S, Morton CL, Howard-Williams EL, Danks MK, Potter PM, Redinbo MR. Structural insights into CPT-11 activation by mammalian carboxylesterases. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9(5):337–342. doi: 10.1038/nsb790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivory LP, Bowles MR, Robert J, Pond SM. Conversion of irinotecan (CPT-11) to its active metabolite, 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN-38), by human liver carboxylesterase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52(7):1103–1111. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nozawa T, Minami H, Sugiura S, Tsuji A, Tamai I. Role of organic anion transporter OATP1B1 (OATP-C) in hepatic uptake of irinotecan and its active metabolite, 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin: in vitro evidence and effect of single nucleotide polymorphisms. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33(3):434–439. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.001909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawato Y, Furuta T, Aonuma M, Yasuoka M, Yokokura T, Matsumoto K. Antitumor activity of a camptothecin derivative, CPT-11, against human tumor xenografts in nude mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1991;28(3):192–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00685508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Ark-Otte J, Kedde MA, van der Vijgh WJ, Dingemans AM, Jansen WJ, Pinedo HM, et al. Determinants of CPT-11 and SN-38 activities in human lung cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 1998;77(12):2171–2176. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohtsuka K, Inoue S, Kameyama M, Kanetoshi A, Fujimoto T, Takaoka K, et al. Intracellular conversion of irinotecan to its active form, SN-38, by native carboxylesterase in human non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003;41(2):187–198. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guichard S, Terret C, Hennebelle I, Lochon I, Chevreau P, Fretigny E, et al. CPT-11 converting carboxylesterase and topoisomerase activities in tumour and normal colon and liver tissues. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(3–4):364–370. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu G, Zhang W, Ma MK, McLeod HL. Human carboxylesterase 2 is commonly expressed in tumor tissue and is correlated with activation of irinotecan. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(8):2605–2611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsieh YT, Lin HP, Chen BM, Huang PT, Roffler SR. Effect of cellular location of human carboxylesterase 2 on CPT-11 hydrolysis and anticancer activity. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi BR, Kim SU, Choi KC. Co-treatment with therapeutic neural stem cells expressing carboxyl esterase and CPT-11 inhibit growth of primary and metastatic lung cancers in mice. Oncotarget. 2014;5(24):12835–12848. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basel MT, Balivada S, Shrestha TB, Seo GM, Pyle MM, Tamura M, et al. A cell-delivered and cell-activated SN38-dextran prodrug increases survival in a murine disseminated pancreatic cancer model. Small. 2012;8(6):913–920. doi: 10.1002/smll.201101879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutova M, Najbauer J, Chen MY, Potter PM, Kim SU, Aboody KS. Therapeutic targeting of melanoma cells using neural stem cells expressing carboxylesterase, a CPT-11 activating enzyme. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010;5(3):273–276. doi: 10.2174/157488810791824421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchino J, Takayama K, Harada A, Sone T, Harada T, Curiel DT, et al. Tumor targeting carboxylesterase fused with anti-CEA scFv improve the anticancer effect with a less toxic dose of irinotecan. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15(2):94–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oosterhoff D, Overmeer RM, de Graaf M, van der Meulen IH, Giaccone G, van Beusechem VW, et al. Adenoviral vector-mediated expression of a gene encoding secreted, EpCAM-targeted carboxylesterase-2 sensitises colon cancer spheroids to CPT-11. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(5):882–887. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meck MM, Wierdl M, Wagner LM, Burger RA, Guichard SM, Krull EJ, et al. A virus-directed enzyme prodrug therapy approach to purging neuroblastoma cells from hematopoietic cells using adenovirus encoding rabbit carboxylesterase and CPT-11. Cancer Res. 2001;61(13):5083–5089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wierdl M, Morton CL, Weeks JK, Danks MK, Harris LC, Potter PM. Sensitization of human tumor cells to CPT-11 via adenoviral-mediated delivery of a rabbit liver carboxylesterase. Cancer Res. 2001;61(13):5078–5082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi SS, Yoon K, Choi SA, Yoon SB, Kim SU, Lee HJ. Tumor-specific gene therapy for pancreatic cancer using human neural stem cells encoding carboxylesterase. Oncotarget. 2016;7(46):75319–75327. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laizure SC, Herring V, Hu Z, Witbrodt K, Parker RB. The role of human carboxylesterases in drug metabolism: have we overlooked their importance? Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(2):210–222. doi: 10.1002/phar.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivory LP, Robert J. Identification and kinetics of a beta-glucuronide metabolite of SN-38 in human plasma after administration of the camptothecin derivative irinotecan. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;36(2):176–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00689205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haaz MC, Rivory L, Jantet S, Ratanasavanh D, Robert J. Glucuronidation of SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan, by human hepatic microsomes. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;80(2):91–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1997.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iyer L, King CD, Whitington PF, Green MD, Roy SK, Tephly TR, et al. Genetic predisposition to the metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11). Role of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase isoform 1A1 in the glucuronidation of its active metabolite (SN-38) in human liver microsomes. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(4):847–854. doi: 10.1172/JCI915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciotti M, Basu N, Brangi M, Owens IS. Glucuronidation of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN-38) by the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases encoded at the UGT1 locus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260(1):199–202. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strassburg CP, Oldhafer K, Manns MP, Tukey RH. Differential expression of the UGT1A locus in human liver, biliary, and gastric tissue: identification of UGT1A7 and UGT1A10 transcripts in extrahepatic tissue. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52(2):212–220. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanioka N, Ozawa S, Jinno H, Ando M, Saito Y, Sawada J. Human liver UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms involved in the glucuronidation of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin. Xenobiotica. 2001;31(10):687–699. doi: 10.1080/00498250110057341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tallman MN, Ritter JK, Smith PC. Differential rates of glucuronidation for 7-ethyl-10-hydroxy-camptothecin (SN-38) lactone and carboxylate in human and rat microsomes and recombinant UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33(7):977–983. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.003491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivory LP, Haaz MC, Canal P, Lokiec F, Armand JP, Robert J. Pharmacokinetic interrelationships of irinotecan (CPT-11) and its three major plasma metabolites in patients enrolled in phase I/II trials. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3(8):1261–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wasserman E, Myara A, Lokiec F, Goldwasser F, Trivin F, Mahjoubi M, et al. Severe CPT-11 toxicity in patients with Gilbert’s syndrome: two case reports. Ann Oncol. 1997;8(10):1049–1051. doi: 10.1023/a:1008261821434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santos A, Zanetta S, Cresteil T, Deroussent A, Pein F, Raymond E, et al. Metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11) by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 in humans. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(5):2012–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dodds HM, Haaz MC, Riou JF, Robert J, Rivory LP. Identification of a new metabolite of CPT-11 (irinotecan): pharmacological properties and activation to SN-38. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286(1):578–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathijssen RH, de Jong FA, van Schaik RH, Lepper ER, Friberg LE, Rietveld T, et al. Prediction of irinotecan pharmacokinetics by use of cytochrome P450 3A4 phenotyping probes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(21):1585–1592. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Bol JM, Mathijssen RH, Creemers GJ, Planting AS, Loos WJ, Wiemer EA, et al. A CYP3A4 phenotype-based dosing algorithm for individualized treatment of irinotecan. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(2):736–742. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sperker B, Backman JT, Kroemer HK. The role of beta-glucuronidase in drug disposition and drug targeting in humans. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33(1):18–31. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199733010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fujisawa T, Mori M. Influence of various bile salts on beta-glucuronidase activity of intestinal bacteria. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;25(2):95–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cole CB, Fuller R, Mallet AK, Rowland IR. The influence of the host on expression of intestinal microbial enzyme activities involved in metabolism of foreign compounds. J Appl Bacteriol. 1985;59(6):549–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1985.tb03359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takasuna K, Hagiwara T, Hirohashi M, Kato M, Nomura M, Nagai E, et al. Involvement of beta-glucuronidase in intestinal microflora in the intestinal toxicity of the antitumor camptothecin derivative irinotecan hydrochloride (CPT-11) in rats. Cancer Res. 1996;56(16):3752–3757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kong R, Liu T, Zhu X, Ahmad S, Williams AL, Phan AT, et al. Old drug new use–amoxapine and its metabolites as potent bacterial beta-glucuronidase inhibitors for alleviating cancer drug toxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(13):3521–3530. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Jong FA, Kehrer DF, Mathijssen RH, Creemers GJ, de Bruijn P, van Schaik RH, et al. Prophylaxis of irinotecan-induced diarrhea with neomycin and potential role for UGT1A1*28 genotype screening: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Oncologist. 2006;11(8):944–954. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-8-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slatter JG, Schaaf LJ, Sams JP, Feenstra KL, Johnson MG, Bombardt PA, et al. Pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and excretion of irinotecan (CPT-11) following I.V. infusion of [(14)C]CPT-11 in cancer patients. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28(4):423–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mathijssen RH, van Alphen RJ, Verweij J, Loos WJ, Nooter K, Stoter G, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11) Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(8):2182–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sugiyama Y, Kato Y, Chu X. Multiplicity of biliary excretion mechanisms for the camptothecin derivative irinotecan (CPT-11), its metabolite SN-38, and its glucuronide: role of canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter and P-glycoprotein. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42(Suppl):S44–S49. doi: 10.1007/s002800051078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chu XY, Kato Y, Ueda K, Suzuki H, Niinuma K, Tyson CA, et al. Biliary excretion mechanism of CPT-11 and its metabolites in humans: involvement of primary active transporters. Cancer Res. 1998;58(22):5137–5143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]