Overview

Introduction

The ilioinguinal approach for psoas recession over the pelvic brim allows for direct visualization and protection of the femoral nerve while preserving hip flexion strength.

Indications & Contraindications

Step 1: Patient Positioning, Preoperative Assessment, and Draping

With the patient supine and anesthetized, perform the Thomas test, administer antibiotics, and drape to provide access to the inferior aspect of the abdomen, ilioinguinal region, and lower limb.

Step 2: Superficial Dissection

Mark the osseous landmarks, draw a line connecting the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle, and make a bikini incision along this line.

Step 3: Deep Dissection

Incise the external oblique aponeurosis and internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle, leaving a 2-mm cuff of tissue.

Step 4: Psoas Recession

After protecting the femoral nerve, confirm the identity of the psoas with 3 tests and transect it with cautery.

Step 5: Postoperative Management

Physical therapy is initiated immediately and includes static and dynamic hip extension exercises that stretch the anterior hips structures.

Results

Hip flexion contracture is a debilitating condition that affects many patients with spastic paresis or prior hip trauma.

Pitfalls & Challenges

Introduction

The ilioinguinal approach for psoas recession over the pelvic brim allows for direct visualization and protection of the femoral nerve while preserving hip flexion strength.

Hip flexion contracture is a common problem in patients with spastic paresis such as cerebral palsy and may also affect patients who have sustained trauma about the hip. These contractures may impair gait and the ability to carry out activities of daily living. The iliopsoas muscle is the main deforming force; however, contraction of the hip capsule and surrounding soft tissue may also contribute1. Iliopsoas tenotomy at the level of the lesser trochanter treats the contracture at the cost of hip flexor strength, making it difficult for ambulatory patients to climb stairs or even walk on a level surface2,3. Intramuscular psoas recession over the pelvic brim is an alternative that preserves hip flexor strength while correcting the flexion contracture4-8. In this procedure, the psoas tendon is lengthened as it traverses the pelvic brim while the iliacus is preserved (Video 1). Thus, the iliopsoas unit is fractionally lengthened, preserving its ability to flex the hip. Previous studies have shown that hip flexion strength against gravity and manual resistance is maintained while improving dynamic pelvic tilt and step length during gait after this procedure4,8.

Video 1.

Introduction to psoas recession over the pelvic brim. An image in the video is copyrighted by, and reproduced with permission of, the AO Foundation, Switzerland.

Traditionally, intramuscular psoas lengthening is performed through the anterior approach to the hip within the intermuscular interval between the tensor fascia and sartorius. This approach provides access to the psoas tendon from its posterolateral surface without direct visualization of the medial femoral neurovascular bundle. Prior anatomic studies demonstrated that the neurovascular bundle may lie as close as 4 mm from the psoas tendon9. Thus, the indirect exposure in the traditional approach places the femoral neurovascular bundle at risk of iatrogenic injury. The ilioinguinal approach is an alternative for performing intramuscular psoas lengthening to treat both hip flexion contractures and internal snapping hip4,10. First, an oblique incision is made along the inguinal ligament from the anterior superior iliac spine, extending distally and medially toward the pubic tubercle. The external oblique fascia and the internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles are released cephalad to the inguinal ligament to access the pelvic brim. Care is taken during this step to protect the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. The femoral nerve is then identified anteromedial to the psoas while the iliacus is identified laterally. Once the femoral nerve is identified, it may be retracted and protected anteromedially to expose the psoas tendon. Rotating and flexing the hip can help to confirm the identity of the psoas tendon before its release9.

The purpose of this article is to describe the ilioinguinal approach for intramuscular psoas lengthening over the pelvic brim with direct exposure of the femoral neurovascular bundle for the treatment of hip contractures while preserving hip flexion strength.

Indications & Contraindications

Indications

Ambulatory children and adults with a hip flexion contracture for which nonoperative therapy has not led to a satisfactory result. Hip flexion contractures are defined by hip flexion in the terminal stance of gait with at least a 10° flexion contracture on static examination.

Contraindications

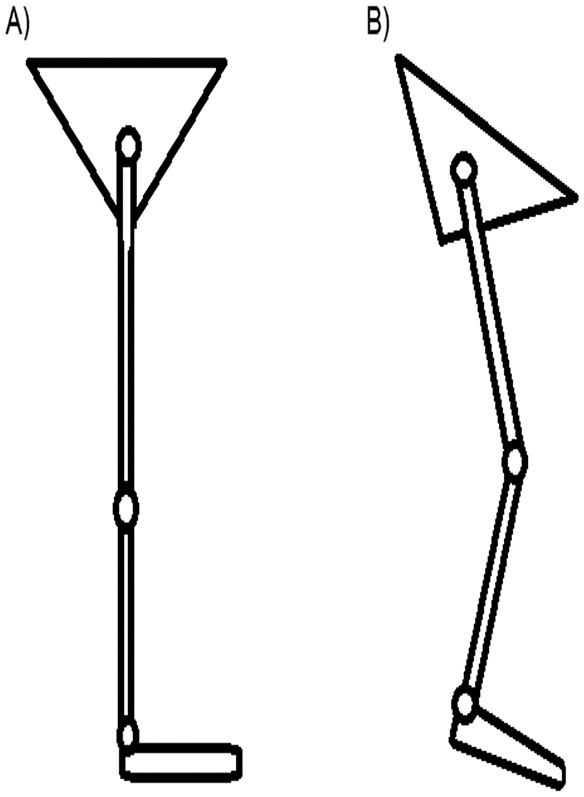

Ipsilateral knee and/or ankle flexion deformities may lead to apparent excessive hip flexion during gait (Fig. 1), with the excessive hip flexion acting as a compensatory mechanism to clear the foot from the floor during swing phase. These distal deformities should be assessed and treated prior to assessment and treatment of the hip flexion contracture.

Concomitant adductor, pelvic, or proximal femoral procedures may require a surgical approach other than the ilioinguinal approach for access.

Fig. 1.

Diagrams of the pelvis and lower limb without knee flexion contracture or ankle equinus (Fig. 1-A) and with knee flexion contracture and ankle equinus deformity (Fig. 1-B). Note the anterior pelvic tilt and apparent compensating hip flexion in Fig. 1-B. This apparent hip flexion may be misdiagnosed as a hip flexion contracture or cause relapse of an appropriately treated hip flexion contracture.

Step 1: Patient Positioning, Preoperative Assessment, and Draping

With the patient supine and anesthetized, perform the Thomas test, administer antibiotics, and drape to provide access to the inferior aspect of the abdomen, ilioinguinal region, and lower limb.

Position the patient supine on a regular table and administer anesthesia. No muscle paralysis is used during the procedure so that activity of the femoral nerve can be monitored when the psoas tendon is recessed with electrocautery.

Once the patient is anesthetized, perform a Thomas test and examine the hip range of motion. To perform the Thomas test, flex the contralateral hip and knee and observe for liftoff of the leg as this suggests a hip flexion contracture (Video 2).

Administer preoperative antibiotics, typically a first-generation cephalosporin, prior to the skin incision for prophylaxis against skin flora that may contaminate the wound. Preoperative antibiotics are especially important for hip flexion contractures about previously implanted devices as those sites may be susceptible to infection.

Prepare and drape the patient in a standard sterile fashion, covering the perineum and carefully leaving it out of the surgical field. Access to the inferior aspect of the abdomen, ilioinguinal region, and leg are paramount for the procedure (Video 2).

Video 2.

Preoperative assessment, patient positioning, and superficial surgical dissection. An image in the video is copyrighted by, and reproduced with permission of, the AO Foundation, Switzerland.

Step 2: Superficial Dissection

Mark the osseous landmarks, draw a line connecting the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle, and make a bikini incision along this line.

Mark the osseous landmarks for the skin incision, which include the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic tubercle.

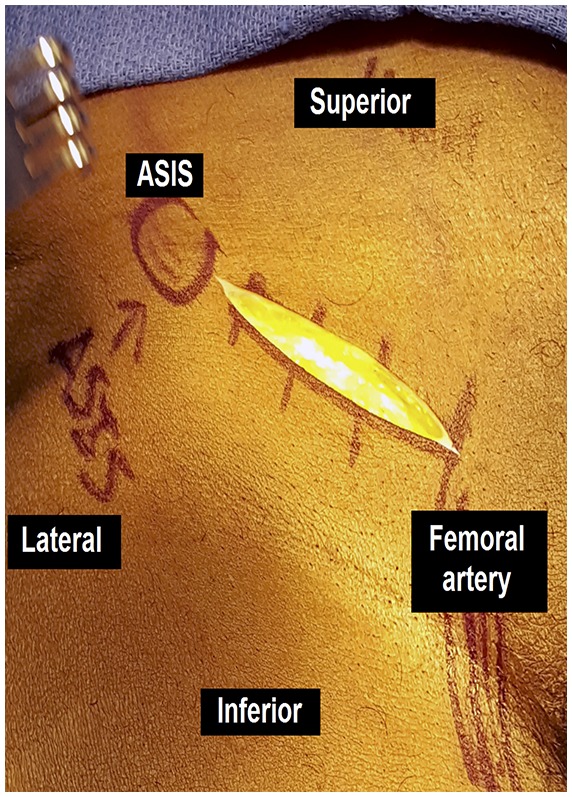

Draw a line drawn connecting the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle. Palpate the femoral artery and mark it as an additional landmark on the skin medially.

Make a 5 to 6-cm bikini incision along the line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle, with the medial extent of the incision ending just lateral to the femoral artery (Fig. 2). This incision is parallel to the Langer lines, allowing the wound to heal with excellent cosmetic results (Video 2).

Fig. 2.

Incision from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the femoral neurovascular bundle in line with the pubic tubercle.

Step 3: Deep Dissection

Incise the external oblique aponeurosis and internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle, leaving a 2-mm cuff of tissue.

Dissect through the subcutaneous tissue to the level of the external oblique aponeurosis.

Palpate the inguinal ligament. Use a Cobb elevator to bluntly dissect subcutaneous fat off of the aponeurosis 1 cm cephalad and caudal to the inguinal ligament. This step will facilitate visualization and closure of the abdominal wall toward the end of this procedure.

Incise the external oblique aponeurosis and underlying internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles parallel to the skin incision from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle, leaving a 2-mm cuff of tissue cephalad to the inguinal ligament. This cuff of tissue from the conjoined tendon will be used to close the abdominal wall during the end of the procedure. Be aware of and protect the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve encountered just deep to the conjoined tendon approximately 1 to 2 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 3).

To improve exposure after releasing the abdominal wall, bluntly dissect longitudinally along the incision using a finger sweep.

Fig. 3.

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) is identified deep to the abdominal fascia in the lateral aspect of the wound.

Step 4: Psoas Recession

After protecting the femoral nerve, confirm the identity of the psoas with 3 tests and transect it with cautery.

The femoral nerve can be visualized on the anteromedial surface of the psoas tendon in the medial aspect of the wound as the tendon traverses the pelvic brim (Fig. 4).

Muscle fibers of the iliacus can be seen lateral to the femoral nerve and psoas tendon. The iliacus muscle is preserved during this procedure to maintain hip flexion strength postoperatively.

Medial to the femoral nerve and psoas tendon is the iliopectineal fascia. Palpate the femoral artery and vein under the iliopectineal fascia for confirmation. Leave the iliopectineal fascia intact to protect the vessels.

Use a gloved finger to dissect lateral to the iliopectineal fascia around the femoral nerve to free it from the psoas tendon.

Place a long right-angle retractor under the femoral nerve to lift the nerve anteriorly and then medially in order to protect it (Fig. 5). If a nonconductive retractor is available, this can be used to isolate the femoral nerve from the electrocautery’s current while the psoas tendon is recessed.

Once the femoral nerve is protected, confirm the identity of the psoas tendon with 3 tests. First, internally and externally rotate and flex and extend the hip while visualizing the psoas tendon. The tendon will move with a passive range of motion of the hip while the femoral nerve will not. Second, confirm that there are proximal muscle fibers coalescing into the tendon. Finally, momentarily touch the tendon with electrocautery or a nerve stimulator. The leg will jerk if the stimulated structure is the femoral nerve but will remain still if it is the psoas tendon (Video 3).

Once the identity of the psoas tendon is confirmed, place a bump or triangle under the knee to flex the knee and hip to take tension off of the psoas and make it easier to lift the tendon off of the pelvic brim. Preserve the iliacus muscle deep and lateral to the psoas to maintain hip flexion strength postoperatively. Use cautery to transect the psoas tendon. Note that the leg may twitch with use of electrocautery if the transection is occurring near a conductive retractor protecting the femoral nerve.

Reassess the hip range of motion. Note that the iliacus muscle is undisturbed by this procedure. Furthermore, the iliopsoas insertion onto the lesser trochanter is preserved.

Copiously irrigate the wound and close it in a layered fashion. First, close the fascia by repairing the abdominal wall and conjoined tendon to the cuff of tissue left cephalad to the inguinal ligament. A good fascial repair is important to prevent formation of an abdominal hernia. Next, close the subcutaneous layer with buried interrupted suture. Finally, close the skin layer. Skin glue may be applied after the sutures to seal the wound from contamination from the nearby perineum. Apply a waterproof dressing at the end of the procedure. Repeat the Thomas test to demonstrate improvement of the hip flexion contracture (Video 3).

Fig. 4.

The femoral nerve overlying the anteromedial surface of the psoas tendon.

Fig. 5.

The arrow shows the psoas tendon after it has been lifted off of the pelvic brim. The asterisk shows a right-angle retractor that is protecting the femoral nerve by lifting it anteriorly and medially from the psoas tendon.

Video 3.

Deep dissection, iliopsoas recession, and postoperative management. Images in the video are copyrighted by, and reproduced with permission of, the AO Foundation, Switzerland.

Step 5: Postoperative Management

Physical therapy is initiated immediately and includes static and dynamic hip extension exercises that stretch the anterior hips structures.

Postoperatively, the patient may proceed with weight-bearing and activity as tolerated.

Perioperative antibiotics are continued for 24 hours after surgery.

Patients at high risk for developing a clot should take aspirin twice a day for 6 weeks for prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis.

Physical therapy, which is initiated immediately after surgery, includes both static and dynamic hip extension exercises that stretch the anterior hip structures that may have contributed to the hip flexion contracture. Patients are also instructed to continue to lie prone at least 4 hours a day for the first 4 weeks after surgery to continue to stretch the anterior aspect of the hip and prevent relapse of the hip flexion contracture. Active, active-assisted, and passive range-of-motion exercises are all permitted immediately following surgery.

Results

Hip flexion contracture is a debilitating condition that affects many patients with spastic paresis or prior hip trauma. Psoas lengthening over the pelvic brim has been a well-established technique to treat this condition4-8. Studies have shown that hip flexion strength is preserved while dynamic pelvic tilt and step length during gait are improved after this procedure4,8. In our experience, patients are also better able to perform other activities of daily living such as sitting in a chair. The traditional approach for psoas lengthening is to use the interval between the tensor fascia and sartorius. This technique, however, does not provide direct visualization and protection of the surrounding neurovascular structures such as the femoral nerve, artery, and vein. The ilioinguinal approach has been previously described for intramuscular psoas lengthening to treat both hip flexion contracture and snapping hip with good results4,10. This present article describes the ilioinguinal approach for intramuscular psoas lengthening to treat flexion contracture while protecting the femoral nerve and preserving hip flexion strength.

The ilioinguinal approach allows the surgeon to directly identify the femoral nerve in the same fascial compartment as the psoas. It also allows for direct visualization and protection of the femoral artery and vein. In our experience, the ilioinguinal approach and psoas recession have restored hip extension and preserved hip flexion strength while avoiding any complications related to femoral nerve palsy.

Pitfalls & Challenges

Concomitant knee and ankle flexion contractures may lead to recurrence of a hip flexion contracture. These deformities should be addressed prior to treating the hip flexion contracture.

Inadequate fascial closure of the abdominal wall may lead to abdominal hernia. Leaving a cuff of tissue cranial to the inguinal ligament during the initial approach facilitates this repair during closure.

Femoral nerve palsy is a devastating complication that may occur if the nerve is not properly differentiated from the psoas tendon. Always perform the 3 checks described in Step 4 to identify and isolate the psoas tendon from the femoral nerve.

Clinically relevant hip flexion weakness may occur if the iliacus is lengthened in addition to the psoas recession. Proper identification of the psoas tendon and iliacus muscle is paramount during surgery. Fractional lengthening of the iliopsoas by lengthening the psoas tendon is preferred over complete transection of both muscles (which occurs when the iliopsoas tendon is released at the level of the lesser trochanter).

Acknowledgments

Note: The authors acknowledge Synthes for allowing them to use its facility to illustrate their technique.

Footnotes

Published outcomes of this procedure can be found at: J Pediatr Orthop. 1997 Sep-Oct;17(5):563-70.

Disclosure: The authors indicated that no external funding was received for any aspect of this work. The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSEST/A157).

References

- 1. Delp SL, Zajac FE. Force- and moment-generating capacity of lower-extremity muscles before and after tendon lengthening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992. November;284:247-59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bleck EE. Postural and gait abnormalities caused by hip-flexion deformity in spastic cerebral palsy. Treatment by iliopsoas recession. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971. December;53(8):1468-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grossheim R, Hoffer MM. The fate of the released iliopsoas tendon in spastic children: a review of 15 hips. Rancho Los Amigos Hosp Rep 1970:105-7. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sutherland DH, Zilberfarb JL, Kaufman KR, Wyatt MP, Chambers HG. Psoas release at the pelvic brim in ambulatory patients with cerebral palsy: operative technique and functional outcome. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997. Sep-Oct;17(5):563-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Novacheck TF, Trost JP, Schwartz MH. Intramuscular psoas lengthening improves dynamic hip function in children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002. Mar-Apr;22(2):158-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Truong WH, Rozumalski A, Novacheck TF, Beattie C, Schwartz MH. Evaluation of conventional selection criteria for psoas lengthening for individuals with cerebral palsy: a retrospective, case-controlled study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011. Jul-Aug;31(5):534-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morais Filho MC, de Godoy W, Santos CA. Effects of intramuscular psoas lengthening on pelvic and hip motion in patients with spastic diparetic cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006. Mar-Apr;26(2):260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bialik GM, Pierce R, Dorociak R, Lee TS, Aiona MD, Sussman MD. Iliopsoas tenotomy at the lesser trochanter versus at the pelvic brim in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009. Apr-May;29(3):251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skaggs DL, Kaminsky CK, Eskander-Rickards E, Reynolds RA, Tolo VT, Bassett GS. Psoas over the brim lengthenings. Anatomic investigation and surgical technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997. June;339:174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gruen GS, Scioscia TN, Lowenstein JE. The surgical treatment of internal snapping hip. Am J Sports Med. 2002. Jul-Aug;30(4):607-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]