Abstract

Background and Objectives

Treosulfan is a prodrug applied in the treatment of ovarian cancer and conditioning prior to stem cell transplantation. So far, the bioanalysis of treosulfan in either whole blood or red blood cells (RBC) has not been carried out. In this work, the RBC/plasma partition coefficient (Ke/p) of treosulfan and its active monoepoxide was determined for the first time.

Methods

Male and female 10-week-old Wistar rats (n = 6/6) received an intraperitoneal injection of treosulfan at the dose of 500 mg/kg body weight. The concentrations of treosulfan and its monoepoxide in plasma (Cp) and RBC were analyzed with a validated HPLC–MS/MS method.

Results

The mean Ke/p of treosulfan and its monoepoxide were 0.74 and 0.60, respectively, corresponding to the blood/plasma partition coefficient of 0.88 and 0.82. The Spearman test demonstrated that the Ke/p of the prodrug correlated with its Cp, but no correlation between the Ke/p and Cp of the active monoepoxide was observed.

Conclusions

Treosulfan and its monoepoxide achieve higher concentrations in plasma than in RBC; therefore, the choice of plasma for bioanalysis is rational as compared to whole blood. The distribution of treosulfan into RBC may be a saturable process at therapeutic concentrations.

Key Points

| Treosulfan and its monoepoxide achieve higher concentrations in plasma than in RBC and whole blood. |

| In contrast to the monoepoxide, the RBC/plasma partitioning of treosulfan seems to be concentration-dependent. |

Introduction

Treosulfan is registered in several European countries for the treatment of advanced ovarian carcinoma in intravenous or oral regimens. The former relies on single dosing of 3–8 g/m2 of the drug every 3–4 weeks [1–3]. Higher intravenous doses, that are 10–14 g/m2 given for 3 consecutive days, have been applied successfully in clinical trial setting to conditioning prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in adult and pediatric populations [4–7]. Currently, phase I–III clinical trials that investigate high-dose treosulfan as an agent prior to HSCT are still ongoing in Europe, the United States, Israel, Australia, and Argentina [8]. Of note, treosulfan is a prodrug which at pH above 5 converts sequentially to the two biologically active epoxy-derivates, the intermediate monoepoxide, (2S,3S)-1,2-epoxy-3,4-butanediol 4-methanesulfonate (S,S-EBDM), and, finally, (2S,3S)-1,2:3,4-diepoxybutane [9–11]. Following administration of treosulfan to humans or animals, the unchanged prodrug and S,S-EBDM have been successfully assayed in plasma, aqueous humor of the eye, and some tissues [12–20]. However, neither in preclinical nor clinical studies, whole blood and red blood cells (RBC) have been analyzed for these two compounds so far. The clearance and volume of distribution of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM that are available in the literature reference only to plasma concentrations [12–17]. Meanwhile, RBC might contain much lower levels of drugs than plasma (e.g., propranolol) or, oppositely, serve as a rich drug reservoir (e.g., cyclophilin A and dorzolamide) [21, 22]. Therefore, in-depth understanding of drug distribution and the physiologically meaningful interpretation of pharmacokinetic parameters warrant investigating of the penetration of drugs into RBC [21, 23–25]. Moreover, the knowledge of RBC partitioning of compounds enables the rational choice of appropriate biological fluid, either plasma or whole blood, that provides the highest possible sensitivity of bioanalysis with a given lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) [21]. In this paper, the RBC/plasma partition coefficient (Ke/p) of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM has been determined in rats. The obtained results provide a new insight into the disposition of treosulfan in the body and enable recalculating of the treosulfan clearance derived from concentrations measured in plasma (Clp) to that referencing to whole blood (Clb).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

A certified reference material of treosulfan for preparation of an injection solution and for analytical purposes was supplied by medac GmbH (Wedel, Germany). Xylazine (Sedazin) was bought from Biowet Puławy (Puławy, Poland) and ketamine (Bioketan) was from Vetoquinol Biowet (Gorzów Wlkp., Poland). Analytical grade citric acid was purchased from Avantor (Gliwice, Poland).

Animals

The studies were carried out in 6 male and 6 female Wistar rats under the approval of the Local Ethics Committee for Experimental on Animals in Poznan, Poland. The number of the animals included in the study (n = 12) was justified by the realization of the principle of the 3Rs (replacement, reduction, and refinement). It was as small as possible but sufficient to evaluate the statistical significance of the correlation between the Ke/p and the drug concentration in plasma (Cp), which required n > 10 according to the rule of thumb. All the animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the European Community guidelines and every possible effort was made to minimise animal suffering. During 7-day adaptation period, the animals were kept in standard cages under a controlled temperature of 22 ± 1 °C, humidity of 55 ± 15%, and lighting (12 h light/dark cycle). Drinking water and standard commercial feed were offered to the rats ad libitum. On the day of treosulfan administration, the animals were 10 weeks old. The body weights of the male and female specimens were 310 ± 10 and 201 ± 14 g (mean ± SD), respectively.

Administration of Treosulfan to Rats and Collection of Plasma and RBC

Treosulfan solution was prepared by dissolving 1000 mg of the drug powder in 20 mL sterile water for injection, according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The freshly prepared solution was administered to the rats as a single intraperitoneal bolus injection at a volume of 10 mL/kg body weight, equivalent to the treosulfan dose of 500 mg/kg body weight. 10 min before blood collection, the animals underwent general anaesthesia with an intraperitoneal bolus injection of ketamine and xylazine at the dose of 50 and 10 mg/kg body weight, respectively. At 1 and 4 h after the treosulfan injection, 4.9 mL of blood was withdrawn from the animals via a heart puncture using S-Monovette 4.9 mL K2EDTA aspiration systems, followed by guillotine euthanasia. Immediately after collection, the blood samples were centrifuged at 3645×g for 5 min at 20 °C. The obtained plasma was always light yellow, which indicated a lack of the RBC lysis. Both the plasma and RBC were transferred into separate vials and acidified with the aqueous solution of 1 M citric acid (50 μL per 1 mL of the sample) at the same time. Thereafter, all the samples were frozen (− 32 °C) and thawed three times on 3 consecutive days to lyse the RBC, and subjected to HPLC analysis.

HPLC–MS/MS Analysis

The Cp of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM were determined with the HPLC–MS/MS method described elsewhere [26]. Briefly, following spiking with the 0.5 mM aqueous solution of codeine (internal standard), the plasma was filtered through Amicon vials (cut-off 30 kDa) to deplete proteins and the obtained filtrate was appropriately diluted with 0.25 mM citric acid solution. The resolution of the analytes and the internal standard was accomplished on Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column using a mobile phase composed of a pH 4.0 formate buffer and acetonitrile (95:5, v/v). To designate the analytes concentrations in the RBC lysates (Ce), 78.8 μL of the sample was spiked with 75 μL of water and 15 μL of the internal standard solution, and vortexed and centrifuged at 15,000×g for 10 min at 20 °C. The resulting supernatant was further processed as plasma. The calibration standards and the quality control samples were prepared in the same manner as the studied samples, except that drug-free RBC lysate (obtained from drug-free RBC after three freeze–thaw cycles) and plasma were spiked with the standard solutions of the analytes instead of water.

Calculation of the Ke/p and Blood/Plasma Partition Coefficient

Treosulfan and S,S-EBDM very weakly bind to rat plasma (unbound fraction ≥ 0.94) and only free drug molecules in plasma partition into RBC [19, 21]. Therefore, the Ke/p of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM was calculated as the ratio of the total concentrations of the analyte determined in the RBC lysate and plasma (Ce/Cp) [21]. Moreover, using the mean Ke/p values and the average physiological hematocrit (Hct) of human and rat blood (0.45), the blood/plasma partition coefficient (Kb/p) of the compounds was estimated from the formula: Kb/p = Ke/p × Hct + 1 − Hct [21, 25].

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of the Cp and Ke/p was performed in Statistica 12 (StatSoft Inc.). The normal distribution of the data was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. As the Cp values were not normally distributed, the Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the degree of association between the Ke/p and Cp. Moreover, the t distribution was employed to statistically evaluate the significance of the calculated Spearman rank correlation coefficient. The null hypothesis stated that there was no correlation between the Ke/p and Cp, and the alternative hypothesis stated that either a positive or negative correlation existed. The null hypothesis was rejected in favour of the alternative one if the calculated t statistic was greater than the critical value of the t distribution for a two-tailed outcome at the level of significance (α) 0.05 and the number of degrees of freedom n − 2, which was 10.

Results

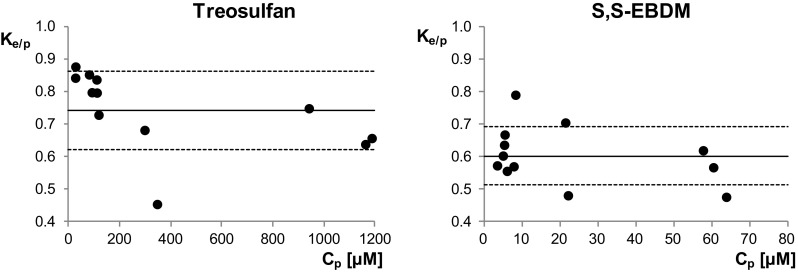

The linearity of the calibration curves, accuracy, and precision for determination of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM in rat plasma and RBC, and the freeze–thaw stability of the analytes are presented in Table 1. The Ke/p values of the compounds obtained in all the 12 rats included in the study (Table 2, Fig. 1) had a normal distribution. The mean and standard deviation computed for the Ke/p of TREO and S,S-EBDM were 0.74 ± 0.12 and 0.60 ± 0.09, respectively. Accordingly, the average Kb/p of the prodrug and its active monoepoxide were estimated to be 0.88 and 0.82. This clearly showed that both the compounds achieve 10–20% higher concentrations in plasma than in whole blood. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient demonstrated a very strong negative association between the Ke/p and Cp of treosulfan (R = − 0.89), which was statistically significant (p = 0.0001). In contrast, the association between the Ke/p and Cp of S,S-EBDM was weak (R = − 0.34) and the Spearman correlation coefficient was not statistically significant (p = 0.2756).

Table 1.

Validation parameters for determination of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM in rat plasma and RBC

| Parameter | Treosulfan | S,S-EBDM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | RBC | Plasma | RBC | |

| Linearity (μM)a | 1.1–110 (curve I) | 1.9–93 | ||

| 110–2209 (curve II) | ||||

| Precision—CV (%)b | ||||

| Within-run (n = 5) | 2.8–7.6 (2.8) | 3.1–9.0 (9.0) | 3.7–19.5 (19.5) | 3.1–5.1 (4.1) |

| Between-run (n = 3) | 1.0–6.1 (6.1) | 2.9–11.1 (4.1) | 3.0–6.0 (6.0) | 2.4–4.0 (4.0) |

| Accuracy (%)b | ||||

| Within-run (n = 5) | 94.7–119.5 (119.5) | 94.3–109.5 (100) | 101.8–109.2 (109.2) | 91.4–109.1 (91.4) |

| Between-run (n = 3) | 97.8–104.6 (104.6) | 85.7–102.9 (85.7) | 102.4–113.2 (113.2) | 95.2–103.9 (95.2) |

| Stability (%) (n = 3)c | 90.7–108.8 | 85.8–104.8 | 88.3–89.4 | 86.7–89.8 |

CV coefficient of variation, LLOQ lowest limit of quantitation, RBC red blood cells, S,S-EBDM (2S,3S)-1,2-epoxy-3,4-butanediol 4-methanesulfonate (treosulfan monoepoxide)

aThe calibration curves were established using the calibration standards at 7–8 concentration levels. For the analysis of treosulfan, two calibration curves were prepared that covered low and high concentrations. The LLOQ was the lowest concentration of the calibration standard

bThe ranges shown in the table include the mean results obtained for the quality control samples containing treosulfan at 1.1, 22, 55, 110, 1104, and 2209 μM, and S,S-EBDM at 1.9, 37, and 94 μM. The values in the parentheses show the results obtained for the LLOQ level

cThe stability values were calculated as a ratio of the final to the initial concentration of the analyte in the samples used in the freeze–thaw stability test. The ranges shown in the table include the mean results obtained for the quality control samples containing treosulfan at 5.5, 55, and 800 μM, and S,S-EBDM at 9.4 and 94 μM

Table 2.

Ke/p of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM determined in rats at 1 and 4 h following intraperitoneal bolus injection of treosulfan at the dose of 500 mg/kg body weight

| Time (h) | Rat no. | Sex | Treosulfan | S,S-EBDM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cp (μM) | Ce (μM) | K e/p | Cp (μM) | Ce (μM) | K e/p | |||

| 1 | 1 | M | 943 | 704 | 0.75 | 58 | 36 | 0.62 |

| 2 | M | 1189 | 779 | 0.66 | 61 | 34 | 0.57 | |

| 3 | M | 28.8 | 24.2 | 0.84 | 3.6 | 2.1 | 0.57 | |

| 4 | F | 1164 | 741 | 0.64 | 64 | 30 | 0.48 | |

| 5 | F | 300 | 204 | 0.68 | 22 | 15 | 0.70 | |

| 6 | F | 349 | 158 | 0.45 | 22 | 11 | 0.48 | |

| 4 | 7 | M | 112 | 94 | 0.84 | 8.0 | 4.5 | 0.57 |

| 8 | M | 120 | 87 | 0.73 | 8.4 | 6.7 | 0.79 | |

| 9 | M | 30 | 26 | 0.87 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 0.64 | |

| 10 | F | 94 | 74 | 0.80 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 0.60 | |

| 11 | F | 113 | 90 | 0.79 | 5.6 | 3.7 | 0.67 | |

| 12 | F | 83 | 70 | 0.85 | 6.2 | 3.4 | 0.56 | |

Ce drug concentration in red blood cells, Cp drug concentration in plasma, F female, Ke/p red blood cells/plasma partition coefficient, M male

Fig. 1.

Plot of the Ke/p of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM against Cp following intraperitoneal bolus injection of treosulfan at the dose of 500 mg/kg body weight. The solid and dotted lines show the mean ± standard deviation. Cp drug concentration in plasma, Ke/p red blood cells/plasma partition coefficient

Discussion

So far, the levels of prodrug treosulfan and S,S-EBDM have not been investigated in whole blood and RBC, neither in humans nor animals, and therefore, the present paper was aimed at determining the Ke/p of these compounds [12–20]. The study was based on the determination of the analyte concentrations in plasma and RBC collected from rats treated with treosulfan at the dose of 500 mg/kg, which is equivalent to 14 g/m2 in adult patients. The levels of the parent drug and S,S-EBDM in the rats’ plasma (Table 2 and Fig. 1) fell into the concentration ranges observed previously in adult and pediatric patients receiving treosulfan prior to HSCT [13–16]. The ex vivo measurement of the Ke/p was favoured over an in vitro approach due to the treosulfan stability reasons. The in vitro experiment requires lowering of blood pH below 5 to halt the rapid nonenzymatic epoxidation of treosulfan to S,S-EBDM (t1/2 1.5 h) as well as the analogous conversion of S,S-EBDM to (2S,3S)-1,2:3,4-diepoxybutane (t1/2 3.4 h) until the RBC/plasma partitioning equilibrium is reached [10]. However, the application of such a methodology was not possible, because it would lead to artificial results due to the fact that RBC lyse at low pH [27]. Only the in vivo approach allowed to catch a real equilibrium of the compounds’ partitioning at physiological conditions. Based on the above considerations, we could not use the in vitro experiment. An animal study was preferred against a clinical one, because treosulfan, as an orphan drug in conditioning prior to HSCT, is presently applied only in special groups of patients who are not eligible to a standard therapy. Moreover, the usage of laboratory animals enabled to obtain a sufficient number of samples for valid statistical analysis from a homogenous group of subjects.

The stability test, performed within validation of the HPLC–MS/MS method (Table 1), demonstrated that the final concentration of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM in the plasma and RBC lysate quality control samples after three freeze–thaw cycles ranged from 85.8 to 108.8% of the initial concentration. The obtained results did not exceed the acceptable threshold for bioanalytical method accuracy (± 15%), which confirmed the usefulness of the freezing and thawing method for the RBC lysis.

Despite treosulfan and S,S-EBDM are nonelectrolytes and very weakly bind to plasma proteins, the compounds partitioned more to plasma than RBC [19, 28]. Of note, the mean Ke/p of treosulfan (Fig. 1) was very close to 0.71. This indicates that the prodrug distributes into the whole intracellular fluid of RBC (which is 0.71 of total RBC volume) but does not bind to erythrocytic binding sites, such as the cell membrane, haemoglobin, or the other cytosol proteins [21]. The result is consistent with the fact that treosulfan easily distributes into the rat liver, lungs, muscles, and bone marrow in vivo, reaching in these tissues the concentrations similar to those in plasma [20]. Lower Ke/p obtained for S,S-EBDM (0.60 ± 0.09) could be surprising taking into account that the epoxide is more lipophilic than treosulfan (log of n-octanol/water partition coefficient − 1.18 vs − 1.58) and has lower molecular weight (182 vs 278 Da) and , therefore, is expected to possess higher capability of diffusing across the RBC membrane [21, 28]. Nevertheless, RBC cytosol contains GSH, glutathione S-transferase, and epoxide hydrolase, which are responsible for the enzymatic utilization of epoxides, for example 1,2:3,4-diepoxybutane [29–33]. Therefore, a hypothesis can be given that the low Ke/p of S,S-EBDM compared to treosulfan results from the metabolism of the epoxide in RBC. Previously, the analogous relations have been found for the distribution of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM into rat lungs as the tissue-to-plasma concentration ratio was about 0.8 and 0.6, respectively [20].

It is worth noting that the estimated Kb/p of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM (0.88 and 0.82) demonstrated that the compounds’ concentrations in plasma are higher than in whole blood. Therefore, determination of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM in the former matrix turns out to be beneficial not only in terms of the convenience of an analytical assay but also somewhat higher sensitivity.

The other importance of Ke/p and Kb/p of drugs lies in their application to calculating physiologically based clearances, volumes of distribution, and organ extraction ratios. It is worth noting that the literature clearance values of treosulfan, which derive from plasma concentrations (Clp), may be only interpreted as the apparent plasma volume cleared of the drug per unit time. In contrast, Clb means the actual volume of blood cleared from the drug per unit time [25]. Based on the results obtained in the present work, it can be estimated that the Clb of treosulfan and S,S-EBDM equal 0.88 Clp and 0.82 Clp, respectively [21, 25].

The partitioning of drugs into RBC proceeds mainly by a passive diffusion across the cell membrane, however, sometimes involves also the transport through channels and carriers. Then, the process may become concentration-dependent and saturable [21, 34]. In this work, no association between the Ke/p and Cp of S,S-EBDM was found, but the Ke/p of treosulfan did correlate negatively with the analyte’s Cp (Spearman R = − 0.89, p = 0.0001). The obtained results indicate that the distribution of the prodrug into RBC undergoes saturation at higher plasma concentrations, including those observed in HSCT patients [13–17]. As treosulfan and S,S-EBDM are unionized at physiological pH and have relatively low molecular size and high hydrophilicity, one may hypothesize that they could permeate the RBC membrane not only by a passive diffusion but also through aquaglyceroporins. These channels are present both in human and rat RBC and demonstrate capability of permeating water, glycerol, and sometimes other noncharged molecules, e.g., urea, mannitol, and sorbitol [21, 35–37]. The saturation of the treosulfan passage via aquaglyceroporins would well explain why the negative correlation between the Ke/p and Cp was observed exclusively for the prodrug, of which plasma levels are approximately 100-fold higher that those of S,S-EBDM. Nevertheless, elucidation of the real mechanisms that account for the results reported here warrants further investigations.

Conclusions

The present study showed for the first time that treosulfan and S,S-EBDM achieve higher concentrations in plasma than in RBC. Therefore, the bioanalysis of these compounds in plasma is rational compared to whole blood. The determined Ke/p values indicate that the Clb of the compounds is 10–20% lower than their Clp.

Funding

The study was financially supported by the National Science Center in Poland (Grant number 2014/13/D/NZ7/00278).

Conflict of interest

The authors, M. Romański, A. Zacharzewska, A. Teżyk, and F.K. Główka, have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. The studies were approved by the Local Ethics Committee for Experimental on Animals in Poznan, Poland (Approval no. 11/2016).

References

- 1.Sehouli J, Tomè O, Dimitrova D, Camara O, Runnebaum IB, Tessen HW, Rautenberg B, Chekerov R, Muallem MZ, Lux MP, Trarbach T, Gitsch G. A phase III, open label, randomized multicenter controlled trial of oral versus intravenous treosulfan in heavily pretreated recurrent ovarian cancer: a study of the North-Eastern German Society of Gynecological Oncology (NOGGO) J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;2017(143):541–555. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treosulfan Injection (medac UK)—Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC). https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/6431. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

- 3.Treosulfan Capsules 250 mg—Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)—(eMC). https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/6426. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

- 4.Główka FK, Romański M, Wachowiak J. High-dose treosulfan in conditioning prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Exp Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:1275–1295. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.517744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burroughs LM, Shimamura A, Talano JA, Domm JA, Baker KK, Delaney C, Frangoul H, Margolis DA, Baker KS, Nemecek ER, Geddis AE, Sandmaier BM, Deeg HJ, Storb R, Woolfrey AE. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation using treosulfan-based conditioning for treatment of marrow failure disorders. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23:1669–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagler A, Labopin M, Beelen D, Ciceri F, Volin L, Shimoni A, Foá R, Milpied N, Peccatori J, Polge E, Mailhol A, Mohty M, Savani BN. Long-term outcome after a treosulfan-based conditioning regimen for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Cancer. 2017;123:2671–2679. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boztug H, Sykora KW, Slatter M, Zecca M, Veys P, Lankester A, Cant A, Skinner R, Wachowiak J, Glogova E, Pötschger U, Peters C. European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation analysis of treosulfan conditioning before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children and adolescents with hematological malignancies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:139–148. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=treosulfan&Search=Search. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

- 9.Hartley JA, O’Hare CC, Baumgart J. DNA alkylation and interstrand cross-linking by treosulfan. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:264–266. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romański M, Urbaniak B, Kokot Z, Główka FK. Activation of prodrug treosulfan at pH 7.4 and 37 °C accompanied by hydrolysis of its active epoxides: kinetic studies with clinical relevance. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104:4433–4442. doi: 10.1002/jps.24662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romański M, Ratajczak W, Główka FG. Kinetic and mechanistic study of the pH-dependent activation (epoxidation) of prodrug treosulfan including the reaction inhibition in a borate buffer. J Pharm Sci. 2017;106:1917–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilger RA, Harstrick A, Eberhardt W, Oberhoff C, Skorzec M, Baumgart J, Seeber S, Scheulen ME. Clinical pharmacokinetics of intravenous treosulfan in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42:99–104. doi: 10.1007/s002800050791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beelen DW, Trenschel R, Casper J, Freund M, Hilger RA, Scheulen ME, Basara N, Fauser AA, Hertenstein B, Mylius HA, Baumgart J, Pichlmeier U, Hahn JR, Holler E. Dose-escalated treosulphan in combination with cyclophosphamide as a new preparative regimen for allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with an increased risk for regimen-related complications. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:233–241. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Główka FK, Karaźniewicz-Łada M, Grund G, Wróbel T, Wachowiak J. Pharmacokinetics of high-dose i.v. treosulfan in children undergoing treosulfan-based preparative regimen for allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(Suppl. 2):S67–S70. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nemecek ER, Guthrie KA, Sorror ML, Wood BL, Doney KC, Hilger RA, Scott BL, Kovacsovics TJ, Maziarz RT, Woolfrey AE, Bedalov A, Sanders JE, Pagel JM, Sickle EJ, Witherspoon R, Flowers ME, Appelbaum FR, Deeg HJ. Conditioning with treosulfan and fludarabine followed by allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for high-risk hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Główka F, Kasprzyk A, Romański M, Wróbel T, Wachowiak J, Szpecht D, Kałwak K, Wiela-Hojeńska A, Dziatkiewicz P, Teżyk A, Żaba C. Pharmacokinetics of treosulfan and its active monoepoxide in pediatric patients after intravenous infusion of high-dose treosulfan prior to HSCT. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2015;68:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romański M, Kasprzyk A, Karbownik A, Szałek E, Główka FK. Formation rate-limited pharmacokinetics of biologically active epoxy transformers of prodrug treosulfan. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105:1790–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romański M, Kasprzyk A, Karbownik A, Główka FK. Ocular disposition of treosulfan and its active epoxy-transformers following intravenous administration in rabbits. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2016;31:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.dmpk.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romański M, Baumgart J, Böhm S, Główka FK. Penetration of treosulfan and its active monoepoxide transformation product into central nervous system of juvenile and young adult rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43:1946–1954. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.066050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romański M, Kasprzyk A, Walczak M, Ziółkowska A, Główka F. Disposition of treosulfan and its active monoepoxide in a bone marrow, liver, lungs, brain, and muscle: studies in a rat model with clinical relevance. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;109:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinderling PH. Red blood cells: a neglected compartment in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Pharmacol Rev. 1997;49:279–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor EA, Turner P. The distribution of propranolol, pindolol and atenolol between human erythrocytes and plasma. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;12:543–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Highley MS, De Bruijn EA. Erythrocytes and the transport of drugs and endogenous compounds. Pharmacol Res. 1996;13:186–195. doi: 10.1023/A:1016074627293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muzykantov VR. Drug delivery by red blood cells: vascular carriers designed by mother nature. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010;7:403–427. doi: 10.1517/17425241003610633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon Y. Clearance. In: Handbook of essential pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and drug metabolism for industrial scientists. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. p. 83–104.

- 26.Romański M, Kasprzyk A, Teżyk A, Widerowska A, Żaba C, Główka F. Determination of prodrug treosulfan and its biologically active monoepoxide in rat plasma, liver, lungs, kidneys, muscle, and brain by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS method. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2017;140:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivanov IT. Low pH-induced hemolysis of erythrocytes is related to the entry of the acid into cytosole and oxidative stress on cellular membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1415:349–360. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(98)00202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Główka FK, Romański M, Siemiątkowska A. Determination of partition coefficients n-octanol/water for treosulfan and its epoxy-transformers: an example of a negative correlation between lipophilicity of unionized compounds and their retention in reversed-phase chromatography. J Chromatogr B. 2013;923–924:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis CD, Hanumegowda UM. The role of drug metabolism in toxicity. In: Nassar AF, Hollenberg PF, Scatina J, editors. Drug metabolism handbook. Concepts and applications. Hoboken: Wiley; 2009. p. 561–81.

- 30.Jiang H, Anderson GD, McGiff JC. The red blood cell participates in regulation of the circulation by producing and releasing epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2012;98:91–93. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van ‘t Erve TJ, Wagner BA, Ryckman KK, Raife TJ, Buettner GR. The concentration of glutathione in human erythrocytes is a heritable trait. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:742–749. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelin K, Hirvonen A, Norppa H. Influence of erythrocyte glutathione S-transferase T1 on sister chromatid exchanges induced by diepoxybutane in cultured human lymphocytes. Mutagenesis. 1996;11:213–215. doi: 10.1093/mutage/11.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porto B, Sousa R, Malheiro I, Gaspar J, Rueff J, Goncalves C, Barbot J. Normal red blood cells partially decrease diepoxybutane-induced chromosome breakage in cultured lymphocytes from Fanconi anaemia patients. Cell Prolif. 2010;43:573–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumoto Y, Ohsako M. Transport of drugs through human erythrocyte membranes: pH dependence of drug transport through labeled human erythrocytes in the presence of band 3 protein inhibitor. J Pharm Sci. 1992;81:428–431. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600810507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonen T, Walz T. The structure of aquaporins. Q Rev Biophys. 2006;39:361–396. doi: 10.1017/S0033583506004458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsukaguchi H, Shayakul C, Berger UV, Mackenzie B, Devidas S, Guggino WB, van Hoek AN, Hediger MA. Molecular characterization of a broad selectivity neutral solute channel. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24737–24743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roudier N, Verbavatz JM, Maurel C, Ripoche P, Tacnet F. Evidence for the presence of aquaporin-3 in human red blood cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8407–8412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]