Abstract

Introduction

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) are a significant health problem in immunocompromised patients, resulting in substantial morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. Micafungin is a broad-spectrum echinocandin with activity against Candida and Aspergillus spp. This was a multicenter, non-comparative, retrospective observational study that evaluated the effectiveness and tolerability of intravenously administered micafungin for treating IFIs caused by Candida and Aspergillus spp.

Methods

Adult patients in China who had received at least one dose of intravenously administered micafungin were eligible. Retrospective data (May 2008–April 2015) were extracted from patients’ medical files and recorded using electronic data capture. The primary endpoint was overall success rate (patients with complete or partial response). Subgroup analyses determined effectiveness according to diagnostic certainty, fungal species, type of IFI, duration of micafungin treatment, and daily dose of micafungin. Tolerability, including the incidence of adverse events (AEs), was also assessed.

Results

Overall, 2555 patients who received at least one dose of micafungin were identified. The mean duration of treatment and mean daily dose were 10.2 days and 133.0 mg, respectively. The overall success rate was 60.8%; this was significantly higher in patients who received treatment for at least 1 week (range 67.9–71.6% [mean 69.2%]) compared with less than 1 week (47.8%; P < 0.0001), and those who received 50–100 mg (65.7%) compared with other daily doses (range 42.9–60.1% [mean 59.0%]; P = 0.0011). Success rates in Candida- and Aspergillus-infected patients were similar (61.9% and 56.8%, respectively). AEs and adverse drug reactions were observed in 36.2% and 4.5% of patients, respectively. The majority of AEs were mild, while discontinuation due to AEs was low (2.3%).

Conclusion

Micafungin is effective and well tolerated for the treatment of patients with IFIs in China, as demonstrated in Candida- and Aspergillus-infected adults. Subgroup analyses highlighted the potential benefits of treating IFIs with micafungin for a minimum of 1 week.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02678598.

Funding

Astellas Pharma Inc.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-018-0762-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aspergillus, Candida, Invasive fungal infections, Micafungin, Real-world data, Retrospective study

Introduction

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) represent an important clinical challenge in immunosuppressed patients, causing substantial morbidity and mortality that result in increased healthcare costs [1, 2]. IFIs are opportunistic and their occurrence has risen in recent decades because of increased numbers of patients undergoing procedures such as hematopoietic stem cell and solid organ transplantation, and receiving chemotherapies for autoimmune conditions and malignancies [1, 3, 4]. In addition, the relative contribution of individual species to IFIs has changed markedly over the last three decades [4]. Candida and Aspergillus are the most commonly reported pathogenic yeast and mold infections in immunocompromised patients in China [5]. The incidence of these infections is currently increasing, which has been attributed to higher rates of hospitalization due to an aging population and an increase in the occurrence of chronic diseases [5].

Micafungin is an echinocandin with broad-spectrum activity against Candida and Aspergillus, as shown in vitro using clinical isolates of these genera [6, 7]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of this agent for the treatment of invasive Candida and Aspergillus infections [1, 8], although licensing of micafungin to treat these infections varies between countries.

In China, micafungin has demonstrated efficacy in the prevention of IFIs in neutropenic patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant. In an open-label study comparing the efficacy and safety of micafungin vs. itraconazole in this population, overall success rates, as measured by the absence of an IFI, were 92.6% and 94.6%, respectively, and better treatment tolerance was observed with micafungin [9]. In a separate study of renal transplant patients with IFIs in China, similar efficacy rates (74.2% vs. 78.8%) were observed between micafungin and voriconazole, respectively [10]. Mortality rates in the micafungin and voriconazole groups were 9.7% and 12.1%, respectively. Both drugs were generally well tolerated with 41.9% and 51.6% of patients experiencing adverse events (AEs) in the micafungin and voriconazole groups, respectively [10].

The aim of the current retrospective study was to evaluate the real-world effectiveness and tolerability of intravenously administered micafungin for IFIs caused by Candida or Aspergillus spp. in adult patients in China.

Methods

Study Design and Treatment

This multicenter, non-comparative, retrospective observational study (ACN-MA-2014-02; Clinicaltrials.gov ID NCT02678598) was conducted at 35 sites in 26 hospitals in China (sites could include hematology departments and intensive care units within the same hospital). Micafungin was administered according to clinicians’ usual clinical practice, and data on all outcome measures were extracted from patients’ medical files and recorded using electronic data capture. In China, the recommended dose range of micafungin is 50–150 mg, which can be increased up to 300 mg/day for severe or refractory candidiasis or aspergillosis; the recommended duration of treatment is 2 and 6–12 weeks in Candida- and Aspergillus-infected patients, respectively, with treatment dose and duration determined according to the severity of disease and the patient’s condition. The observation period was the time between the first dose of micafungin and the end/discontinuation of treatment.

Patients

The study evaluated patients who had received at least one dose of intravenously administered micafungin between May 2008 and April 2015. Male or female patients, aged 18 years or more who were prescribed micafungin as empirical (driven by a pre-emptive diagnosis according to European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group [EORTC/MSG] criteria) [11] or targeted antifungal therapy were considered for participation. Patients were excluded if they received concomitant administration of other antifungal agents, and if the patient’s medical records were missing data and/or unclear.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disease Characteristics

Assessments performed included the overall diagnoses (i.e., possible, probable, or proven), the type of IFI (i.e., Aspergillus or Candida, if confirmed), any identifiable disease, the duration of treatment, assessment of fever, imaging examinations (reported as normal or abnormal findings), and mycological examinations (e.g., including blood or sputum culture, β-d-glucan test, and microscopy of sputum culture; reported as positive or negative). Resolution of fever, other symptoms and signs, imaging abnormalities, and mycological evidence of pathogen clearance were subsequently evaluated at the end/discontinuation of treatment and used to inform assessments for the primary endpoint. All assessments and diagnoses were performed according to the judgment of the treating physician, who worked within the diagnostic framework of EORTC/MSG criteria.

Outcome Measures

Effectiveness

The primary endpoint was the overall success rate, which was defined as the proportion of patients with complete or partial responses. The proportions of patients who died, had disease progression, or had a stable response were also calculated. Definitions of the response categories used are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Subgroup Analyses for Effectiveness

Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of micafungin according to the diagnostic certainty (possible, probable, and proven); fungal organism (Candida or Aspergillus); the type of invasive disease (fungemia, respiratory mycosis [suspected or clinically confirmed pneumonia due to Candida or Aspergillus spp.], or gastrointestinal mycosis [suspected or confirmed gastroenteritis, i.e., diarrhea and abdominal pain, or incidence confirmed by fecal culture, respectively]); the duration of micafungin treatment (< 1, ≥ 1 to < 2 weeks, ≥ 2 to < 4 weeks, and ≥ 4 weeks); and the daily dose of micafungin (0–50, 50–100, 100–150, 150–200, and 200–300 mg).

Tolerability

The secondary endpoints were the incidences of AEs and adverse drug reactions (ADRs). ADRs were defined as events that were, in the opinion of the investigator, possibly or probably related to micafungin treatment. Serious ADRs that occurred from the day of the first dose to 1 week after the end of treatment were included in the analysis. Additional tolerability measures included routine blood, urine, and hepatic and renal function tests conducted during treatment. Any clinically relevant changes in these parameters were recorded as AEs or ADRs.

Statistical Analyses

Enrollment of 3000 patients across 35 sites was planned. For the effectiveness analyses, the primary population was the full analysis set (FAS), defined as all patients whose records showed that they had received at least one dose of micafungin and had an effectiveness assessment. Effectiveness analyses were also conducted using a per-protocol set (PPS) which comprised all subjects who received at least 1 week of treatment (for Aspergillus infection with hematology disease, this was at least 4 weeks) and who did not meet any of the following criteria: inclusion/exclusion violations; micafungin treatment combined with acyclovir or ganciclovir that affected the assessment of study endpoints (based on reduced potency of micafungin when received in combination with these products, as mentioned in the Chinese package insert for micafungin); dosage of micafungin that exceeded 300 mg/day; or off-label use of micafungin. The tolerability analyses were conducted in a safety analysis set (SAS), which was defined as all patients who received at least one dose of micafungin and had at least one safety assessment.

All data were reported descriptively, using means accompanied by asymptotic 95% confidence intervals (CI) to indicate precision. The effect of treatment duration and dose on the overall treatment success rates were analyzed using a chi-square test; P values less than 0.05 were required for the difference between two groups to be considered significant. Analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System version 9.3, or above.

Results

Patients

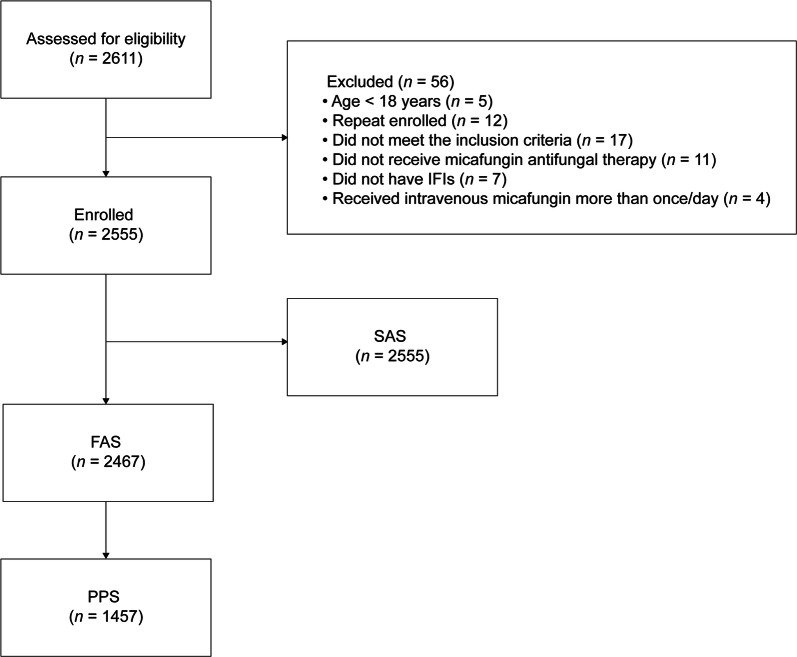

The study was conducted between January and December 2015, with April 30, 2015 as the end time point for patients receiving micafungin treatment. Overall, data from 2611 patients were screened, and 56 excluded, resulting in 2555 enrolled patients whose records showed that they had received at least one dose of micafungin (Fig. 1). These patients were included in the SAS, while the FAS and PPS comprised 2467 and 1457 patients, respectively. No patients were excluded from the PPS as a result of acyclovir or ganciclovir affecting the assessment of study endpoints. The mean (standard deviation; SD) age was 56 (± 18.9) years and most patients (61.4%) were male. Disease characteristics (including the confirmed diagnosis, the organism causing the infection, the type of disease, and the duration of treatment) are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients had a possible diagnosis (n = 1717 [69.6%]), while the remaining patients had probable (n = 699 [28.3%]) or proven (n = 51 [2.1%]) diagnoses. Most patients did not undergo imaging examinations, but abnormalities were reported in up to 37.1% who received any single type of imaging examination. Overall, 1192 (48.3%) patients received a mycological examination; 17.1% of patients in the FAS had a positive result. The infecting organism was not established in 2092 (84.8%) cases; however, where the organism was identified, a higher proportion were infected with Candida (294 [11.9%]) than Aspergillus (81 [3.3%]). Respiratory mycosis was the most frequently encountered fungal disease (n = 1063; 43.1%); the infected site was not established in over half of cases (n = 1325; 53.7%). Diagnoses with fever before receiving micafungin was reported in 1403 [57.1% of 2458]) patients assessed. Corresponding data for the PPS population (organism causing the infection, type of disease, and duration of treatment) are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition. FAS full analysis set, IFI invasive fungal infection, PPS per-protocol set, SAS safety analysis set

Table 1.

Distribution of patients according to disease characteristics and the duration of treatment (FAS)

| Diagnostic certainty, n (%) | n = 2467 |

| Possible | 1717 (69.6) |

| Probable | 699 (28.3) |

| Proven | 51 (2.1) |

| Type of IFI, n (%) | n = 2467 |

| Aspergillus-infected patients | 81 (3.3) |

| Candida-infected patients | 294 (11.9) |

| Not identifiable | 2092 (84.8) |

| Diseases, n (%) | n = 2467 |

| Gastrointestinal mycosisa | 23 (0.9) |

| Fungemia | 56 (2.3) |

| Respiratory mycosisb | 1063 (43.1) |

| Not identifiable | 1325 (53.7) |

| Duration of treatment, n (%) (weeks) | n = 2467 |

| ≥ 4 | 102 (4.1) |

| ≥ 2 to < 4 | 518 (21.0) |

| ≥ 1 to < 2 | 874 (35.4) |

| < 1 | 973 (39.4) |

| Fever, n (%) | (n = 2458)c |

| Yes | 1403 (57.1)d |

| No | 986 (40.1) |

| Not examined | 69 (2.8) |

| Imaging examinations, n (%)e | |

| Chest radiography | n = 2467 |

| Normal | 23 (0.93)f |

| Abnormal | 438 (17.8)f |

| Not examined | 2006 (81.3) |

| Chest CT | (n = 2462)g |

| Normal | 20 (0.8)h |

| Abnormal | 914 (37.1)h |

| Not examined | 1528 (62.1) |

| Other imaging examination | (n = 2465)i |

| Normal | 15 (0.6)j |

| Abnormal | 92 (3.7)j |

| Not examined | 2358 (95.7) |

| Mycological examinations, n (%) | n = 2467 |

| Positive | 422 (17.1) |

| Negative | 770 (31.2) |

| Not examined | 1275 (51.7) |

CT computed tomography, FAS full analysis set, IFI invasive fungal infection, SD standard deviation

aGastrointestinal mycoses were suspected or confirmed gastroenteritis (diarrhea and abdominal pain, or incidence confirmed by fecal culture, respectively)

bRespiratory mycoses included suspected or clinically confirmed pneumonia due to Candida or Aspergillus spp.

cData unavailable from nine patients; gfive patients; and iseven patients for fever, chest CT, and other imaging examinations, respectively

dBody temperature (mean [± SD]) of patients with fever was 38.6 °C (± 0.7); data were collected from 1400 patients (missing data, n = 3)

ePatients may have received more than one type of imaging examination

fThe longest diameter of the lesion was measurable for n = 6 (0.2% of 438 patients); hn = 42 (1.7% of 914 patients); and jn = 5 (0.2% of 92 patients) for chest radiography, chest CT, and other imaging examinations, respectively

Treatment

The mean duration of micafungin treatment was 10.2 days (95% CI 9.9–10.6) and the mean daily dose was 133.0 mg (95% CI 131.6–134.3).

Outcome Measures

Effectiveness

The overall success rate in the FAS (primary endpoint) was 60.8% (95% CI 58.8–62.7) (Table 2). Rates of complete response, partial response, stable disease, disease progression, and mortality in the FAS are also summarized in Table 2. Complete responses were observed in 17.2% (95% CI 15.7–18.7) of patients and partial responses in 43.5% (95% CI 41.6–45.5). The overall mortality rate was 6.7% (95% CI 5.7–7.7). Rates of resolution of fever, other signs and symptoms, imaging abnormalities, and mycological evidence of pathogen clearance in the FAS are summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

Table 2.

Response, progression, and mortality rates during micafungin treatment (FAS [n = 2467])

| Comprehensive assessment of effectiveness, n (%); 95% CIa | |

| Complete response | 425 (17.2); 15.7–18.7 |

| Partial response | 1074 (43.5); 41.6–45.5 |

| Stable response | 473 (19.2); 17.6–20.7 |

| Progression of disease | 330 (13.4); 12.0–14.7 |

| Death | 165 (6.7); 5.7–7.7 |

| Evaluation of overall success rate of patients at the end of treatment, n (%), 95% CI | |

| Failure | 968 (39.2); 37.3–41.2 |

| Response | 1499 (60.8); 58.8–62.7 |

CI confidence interval, FAS full analysis set

aAsymptotic 95% CIs of the percentage response rate calculated

In the PPS, the overall success rate was 69.1% (95% CI 66.7–71.5). Results for rates of complete response, partial response, stable disease, disease progression, and mortality were similar to those in the FAS (Supplementary Table 4).

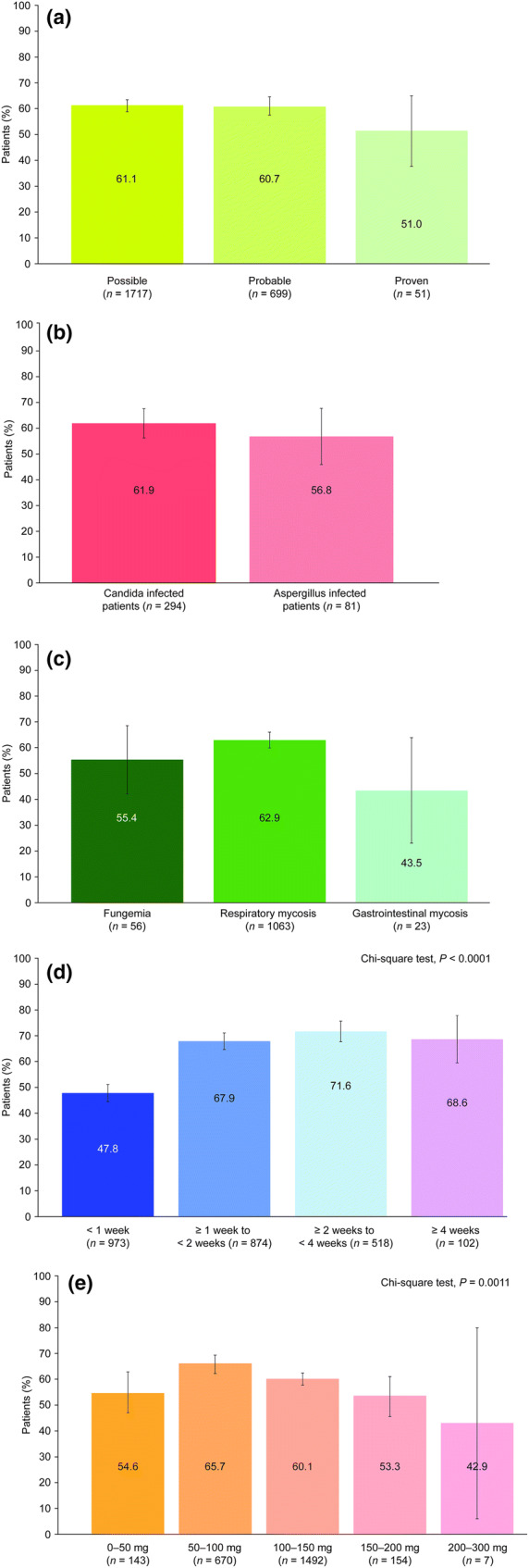

Subgroup Analyses for Effectiveness

The overall success rates according to the subgroup analyses in the FAS are shown in Fig. 2. Overall success rates were numerically higher among patients with a possible or a probable diagnosis (61.1% [95% CI 58.8–63.4] and 60.7% [95% CI 57.0–64.3], respectively), compared with those who had a proven diagnosis (51.0% [95% CI 37.3–64.7]). According to the causative organism, overall success rates were similar for Candida-infected patients (61.9%) vs. Aspergillus-infected patients (56.8%). Stratification according to disease type suggested higher resolution among patients with respiratory mycosis (62.9%) compared with fungemia (55.4%) or gastrointestinal mycosis (43.5%). From a statistical perspective, the overall success rate was significantly higher in each group of patients who received treatment for a longer duration; i.e., ≥ 1 week (range 67.9–71.6%; mean 69.2%), compared with < 1 week (47.8%) (chi-square test P < 0.0001), including the comparison of ≥ 1 to < 2 weeks’ treatment duration compared with < 1 week (47.8% vs. 67.9%, respectively; P < 0.0001). When stratification was performed by daily dose, the highest overall success rates were reported with doses of 50–100 mg (65.7%) and 100–150 mg (60.1%); significant differences were reported for these doses compared with a higher daily dose (e.g., 200–300 mg [42.9%]) (P = 0.0011).

Fig. 2.

Overall success rates (proportion of patients with complete or partial response) at the end of treatment according to diagnostic certainty (a); the organism causing the infection (b); type of disease (c); treatment duration (d); and the daily dose (e) in the FAS. P values indicate significant differences between treatment groups (providing there is also a clear difference in the proportion of patients with a complete or partial response); error bars represent asymptotic 95% confidence intervals. FAS full analysis set

Corresponding results for patients in the PPS are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Overall success rates in subgroups defined by the diagnostic certainty, fungal organism, and disease type were slightly higher than those in the FAS, which reflects exclusion from the PPS of patients who received treatment for less than 1 week. Consistent with the FAS, significant differences were reported when stratification was performed by daily dose (P = 0.0003); however, there was no significant effect of treatment duration on overall success rates in the PPS.

Tolerability

The overall tolerability profile of micafungin is summarized in Table 3. In total, AEs were observed in 925 (36.2%) patients and ADRs were observed in 116 (4.5%) patients. In most cases (more than 50%), the severity of the AEs was mild. AEs that occurred in more than 1% of patients are shown in Supplementary Table 5; the most common AEs were dyspnea, diarrhea, and pulmonary infection, observed in 58 (2.3%), 56 (2.2%), and 55 (2.2%) patients, respectively. The most common ADRs were abnormal hepatic function (19 patients [0.7%]); diarrhea (14 patients [0.6%]); rash (12 patients [0.5%]); and decreased platelet counts, fever, and peripheral edema (5 patients each [0.2%]).

Table 3.

Overall tolerability profile of micafungin (SAS [n = 2555])

| Number of patients (%) | Number of events | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall AEs | 925 (36.2) | 1989 |

| Mild | 606 (23.7) | 1150 |

| Moderate | 266 (10.4) | 414 |

| Severe | 269 (10.5) | 425 |

| ADRs considered to be drug related | 116 (4.5) | 177 |

| Probably related | 4 (0.2) | 6 |

| Possibly related | 113 (4.4) | 171 |

| SAEs | 190 (7.4) | 297 |

| Serious ADRs | 5 (0.2) | 9 |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 59 (2.3) | 92 |

ADRs adverse drug reactions, AEs adverse events, SAEs serious AEs, SAS safety analysis set

Fifty-nine patients (2.3%) discontinued as a result of AEs. Five patients (0.2%) had nine serious ADRs, which were possibly related to the study drug, and one of these patients discontinued treatment. The ADRs comprised one patient who experienced pulmonary infection, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiple organ failure; one patient who experienced postoperative sepsis with liver metastasis of gastric cancer; one patient who experienced shortness of breath and chest tightness; one patient who experienced respiratory failure; and one patient who experienced septic shock. Two patients experienced severe ADRs that were life-threatening. Three patients (0.1%) with severe ADRs died: one patient who experienced pulmonary infection, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiple organ failure; one who experienced respiratory failure; and one who experienced postoperative sepsis and liver metastasis associated with gastric cancer.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis in adult patients in China provides real-world evidence that intravenously administered micafungin is effective against IFIs caused by Aspergillus and Candida when used as empirical antifungal therapy, driven by a pre-emptive diagnosis and targeted antifungal therapy.

The overall success rates observed in this retrospective analysis were broadly comparable with those seen with other antifungal agents in Chinese patients with IFIs. In a retrospective analysis of data from patients treated with amphotericin B for IFIs, an overall response rate of 76% was observed [12], while an overall response rate of 67.3% was observed in a Chinese study evaluating the efficacy of amphotericin B for IFIs in patients with hematologic diseases [13]. In a further randomized study comparing prophylactic posaconazole and fluconazole for the prevention of IFIs in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome, the overall incidences of possible, probable, or proven IFIs were 9.4% and 22.2% in each treatment group, respectively [14]. Again, it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding the relative efficacy of micafungin vs. these agents as these are not head-to-head evaluations, and such between-study comparisons should be made with caution.

Stratification of the findings by treatment duration and the daily dose received indicated that micafungin treatment is most effective when continued for longer than 1 week, or if prescribed between 50 and 100 mg/day. Results suggesting that increasing the treatment length beyond 1 week is more effective than a shorter treatment duration were also reflected in the difference between the overall success rates in the FAS and the PPS, which excluded patients who received treatment for less than 1 week. This is a potentially important finding which emphasizes the importance of treating high-risk patients with IFIs for a minimum duration of 14 days, as demonstrated in recent studies of micafungin in transplant patients in China [10, 15], and in accordance with the Chinese summary of product characteristics for micafungin. The results from this study were not stratified by disease severity, but it is possible this may have had an impact on the findings observed for treatment duration.

Findings that suggest micafungin is most effective when dosed between 50 and 100 mg/day are in line with the Chinese label for micafungin (50 or 100 mg for the treatment of patients with invasive candidiasis or aspergillosis), and European and US guidelines for the treatment of invasive candidiasis (which recommend micafungin 100 mg as initial, targeted treatment; the latter in non-neutropenic patients) [16, 17]. Of note, micafungin is not currently indicated for the treatment of infections caused by Aspergillosis spp. in Europe or the USA [18, 19]. However, some limitations are clear with regards to the subgroup analyses that were performed. Firstly, there were substantial differences between the patient numbers included in different groups analyzed, with small numbers included in some groups; unfortunately, it was not possible to combine groups after the analyses were performed. Secondly, no objective measure was used to determine a clear difference in percentage overall success rate, which was also required to infer significance if a P value of less than 0.05 was reported; any measures of significance were subjective and are therefore limited. These issues with the subgroup analyses limit the conclusions that can be inferred.

The findings from the current analyses showed that micafungin is well tolerated, with a low incidence of ADRs, serious ADRs, and AEs leading to discontinuation of treatment. Overall, the data add to the growing body of evidence demonstrating the effectiveness and tolerability of micafungin for the treatment of patients with invasive fungal infections; however, it is difficult to compare this trial directly with others because of differences in the patient populations and in the way that treatment success was evaluated [1, 8–10, 20, 21].

The strengths of this study are that it included a large patient population and that it provides real-world evidence of micafungin effectiveness and tolerability in current clinical practice. It should also be noted that the results may represent a conservative estimate of the effectiveness of micafungin, as patients whose symptom resolution data were unavailable were assumed to be non-responders. Limitations of the study include its retrospective design and the lack of a comparator arm; also, the study design did not stratify patients by treatment approach (i.e., empirical- or diagnostic-driven antifungal therapy); therefore, the overall success rates reported were derived using resolution/improvement in fever symptoms alone, in a subset of patients whose data were not further evaluated. The small proportion of patients in the FAS who received imaging or mycological examinations may have contributed to the lack of identifiable disease or type of IFI, and imaging and mycological assessments were limited by the use of inconsistent methodology before and after treatment, or a lack of reassessment following treatment. Also, the small patient numbers included in some subgroups may have limited the statistical analyses. It would therefore be worthwhile conducting a randomized, active-controlled study with micafungin in Chinese patients with IFIs, to confirm the findings reported and provide head-to-head data. Long-term safety data for patients treated with micafungin in a real-world setting would also be beneficial; this is an objective of a large, multicenter, observational cohort study conducted in the USA (MYCOS; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01686607), which is due for completion in January 2020 [22].

Conclusion

This retrospective study in real-world clinical practice indicates that micafungin is effective and well tolerated as antifungal treatment in Chinese adults with IFIs. Furthermore, micafungin appeared to be effective in treating both Candida and Aspergillus infections, irrespective of the diseases evaluated. Notably, worse outcomes were observed in patients with a short duration of treatment; thus, this should be addressed by highlighting a minimum duration for the treatment of IFIs with micafungin, which could be implemented in clinical practice and medical education programs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This study was initiated and funded by Astellas Pharma Inc. The article processing charges and the open access fee were also funded by Astellas Pharma Inc. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing support, which was funded by Astellas Pharma Inc, was provided by Nicola French, PhD and Lucy Kanan, PhD of Bioscript Medical.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Xiaoyun Zheng, Xiaobo Huang, Jianmin Luo, Juan Li, Wei Li, Qifa Liu, Ting Niu, Xiaodong Wang, Jianfeng Zhou, Xi Zhang, Jianda Hu, and Kaiyan Liu have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the Astellas China data policy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data requests will be assessed individually for confidentiality, patient consent, and compliance with applicable regulations prior to being made available.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.6865253.

Contributor Information

Jianda Hu, Email: drjiandahu@163.com.

Kaiyan Liu, Email: liukaiyan@medmail.com.cn.

References

- 1.de la Torre P, Reboli AC. Micafungin: an evidence-based review of its place in therapy. Core Evid. 2014;9:27–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drgona L, Khachatryan A, Stephens J, et al. Clinical and economic burden of invasive fungal diseases in Europe: focus on pre-emptive and empirical treatment of Aspergillus and Candida species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:7–21. 10.1007/s10096-013-1944-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornely OA. Aspergillus to Zygomycetes: causes, risk factors, prevention, and treatment of invasive fungal infections. Infection. 2008;36:296–313. 10.1007/s15010-008-7357-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kriengkauykiat J, Ito JI, Dadwal SS. Epidemiology and treatment approaches in management of invasive fungal infections. Clin Epidemiol. 2011;3:175–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao Y, Chen M, Hartmann T, Yang RY, Liao WQ. Epidemiology of opportunistic invasive fungal infections in China: review of literature. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:361–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messer SA, Diekema DJ, Boyken L, Tendolkar S, Hollis RJ, Pfaller MA. Activities of micafungin against 315 invasive clinical isolates of fluconazole-resistant Candida spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:324–6. 10.1128/JCM.44.2.324-326.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfaller MA, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, et al. In vitro susceptibility of clinical isolates of Aspergillus spp. to anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin: a head-to-head comparison using the CLSI M38-A2 broth microdilution method. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3323–5. 10.1128/JCM.01155-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanadate T, Wakasugi M, Sogabe K, et al. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of micafungin in Japanese patients with deep mycosis: a post-marketing survey report. J Infect Chemother. 2011;17:622–32. 10.1007/s10156-011-0219-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang X, Chen H, Han M, et al. Multicenter, randomized, open-label study comparing the efficacy and safety of micafungin versus itraconazole for prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2012;18:1509–16. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shang W, Feng G, Sun R, et al. Comparison of micafungin and voriconazole in the treatment of invasive fungal infections in kidney transplant recipients. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37:652–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2012.01362.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1813–21. 10.1086/588660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma XJ, Li GP, Zhou J, Wang A, Li TS. A retrospective study of amphotericin B treatment for invasive fungal infection. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2007;46:718–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia L, Huang M, Liu WL, et al. Clinical analysis of amphotericin B in the treatment of invasive fungal infections in 121 patients with hematologic diseases. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2008;29:619–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen Y, Huang XJ, Wang JX, et al. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole as invasive fungal infection prophylaxis in China: a multicenter, randomized, open-label study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51:738–45. 10.5414/CP201880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan T, Li SL, Wang DX. Comparison between micafungin and caspofungin for the empirical treatment of severe intra-abdominal infections in surgical intensive care patients. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2016;96:2301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornely OA, Bassetti M, Calandra T, et al. ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: non-neutropenic adult patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:19–37. 10.1111/1469-0691.12039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409–17. 10.1093/cid/civ1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Electronic Medicines Compendium. EU summary of product characteristics for micafungin. 2018. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/20997/SPC/Mycamine+50mg+and+100mg+powder+for+solution+for+infusion/. Accessed June 2018.

- 19.Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing information for micafungin. 2018. https://www.astellas.us/docs/mycamine.pdf/. Accessed June 2018.

- 20.Chen GL, Chen Y, Zhu CQ, Yang CD, Ye S. Invasive fungal infection in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:1087–91. 10.1007/s10067-012-1980-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enoch DA, Idris SF, Aliyu SH, Micallef C, Sule O, Karas JA. Micafungin for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis. J Infect. 2014;68:507–26. 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinicaltrials.gov. Trial record for NCT01686607: Short and long-term safety of micafungin and other parenteral antifungal agents (MYCOS). 2018. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01686607?term=MYCOS&rank=1/. Accessed 26 April 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the Astellas China data policy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data requests will be assessed individually for confidentiality, patient consent, and compliance with applicable regulations prior to being made available.