Abstract

Calls for a more tailored approach to the management of cardiometabolic and musculoskeletal diseases have been increasing. Although tailored care is a centuries-old concept, it is still unclear how it should be best practised. The current paper introduces two phenotype-based Dutch approaches to support tailored care. One approach focuses on patients with type 2 diabetes, the other on patients undergoing total joint replacement. Using the patient profiling approach, both projects propose that care can be tailored by the assessment of biopsychosocial patient characteristics, stratification of patients into subgroups of patients with similar care needs, abilities, and preferences (so-called patient profiles) and tailoring of care in concordance with the common care preferences of these profiles. In this article, the advantages and disadvantages of the method are discussed to enable researchers or clinicians who want to extend the patient profiling approach to other patient populations to carefully evaluate these in relation to their project’s focus and available resources.

Funding: Novo Nordisk B.V., the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) (Grant 314-99-118) and Zimmer Biomet Inc.

Keywords: Patient preferences, Patient profiling, Personalization, Tailoring, Value-based care

Introduction

Tailored care was first described 4000 years BC in sacred texts from India known as the Vedas [1]. It was then called Ayurvedic medicine and its aim was to tailor treatment to each person’s prakriti (or constitution) in order to maintain a balance between body, mind and spirit. Nowadays, the aim of tailored care is to improve patients’ health outcomes and care experience by taking their individual needs and preferences into account in developing a treatment plan. As a result of the aging population and associated growing burden of cardiometabolic and musculoskeletal diseases [2], calls for a more tailored approach to the management of diseases have been increasing [3–5]. Although tailored care is millennia old, it is still unclear what the best approach is.

Currently, the majority of patients receive standardized care, based on evidence-based, disease-specific guidelines [6, 7]. However, there is a growing body of evidence that shows the inherent limitations of this ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. For example, patients differ in the amount and type of information they need and which aspects of care they prioritize [8–10]. While healthcare professionals do tailor communication during medical consultation to some extent, neither care needs nor preferences are routinely accommodated [10, 11]. Thus, we need to think of other ways to deliver care. A tailored approach based on the phenotyping of patients may be such an approach. In this approach, patients’ biopsychosocial characteristics are used to identify subgroups of patients with similar care needs, abilities and preferences, for whom tailored solutions can be developed.

In the current paper we introduce two phenotype-based Dutch approaches to support tailored care. One approach focuses on patients with type 2 diabetes, the other on patients who undergo total joint replacement. Both use the term patient profiles to represent identified subgroups of patients, which form the basis for the development of tailored care, and are set to deliver final results in 2018–2019. Here, we outline the common steps in patient profiling, with a detailed description of their development, focusing on the differences in the patient characteristics assessed to identify the profiles and the process by which patients were stratified into subgroups.

Patient Profiling

The aim of patient profiling is to enable care providers to provide the right care, to the right person, at the right time. It draws on the concept of ‘mass customization’, where goods and services are delivered to a large number of clients with enough variety and customization that nearly everyone finds exactly what they want [12]. Starbucks, Levi’s and Burger King are prominent examples of companies that have implemented this concept of targeting ‘markets of a few’ [13]. At Starbucks, for example, customers can customize their coffee by choosing from a variety of sizes, flavours and toppings. In healthcare, mass customization is less well known, but with many patients with specific diseases that have varying care needs, abilities and preferences, it could be a solution for delivering more tailored healthcare.

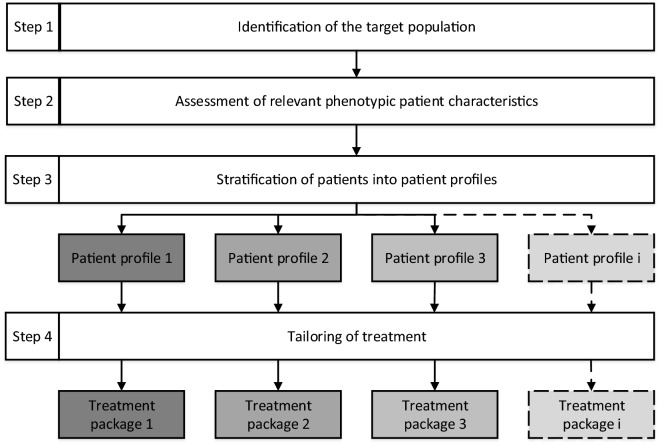

Patient profiling uses the individual’s preferences to tailor the content, context and delivery mode of care to improve care experience and health outcomes [14–16], including quality of life, as well as reducing the per capita costs of care. The development of the tailored care based on profiles consists of four steps: (1) identification of the target population, (2) assessment, (3) stratification, and (4) tailoring (Fig. 1). After defining the population (e.g. patients with type 2 diabetes treated in primary care), care providers assess relevant phenotypic patient characteristics, such as body weight, quality of life and self-efficacy, which are predictive of relevant outcomes, such as glycaemic control and patient satisfaction. Subsequently, these characteristics are used to stratify patients into profiles. This approach results in subgroups of patients who are more homogeneous than the population as a whole in terms of care needs, abilities and preferences, while acknowledging that a certain amount of heterogeneity within these subgroups will remain. In the last step, the patient’s care is adapted depending on his or her profile.

Fig. 1.

The patient profiling approach. Treatment packages may differ in frequency of consultations, education material, etc.

Comparison of Two Patient Profiles Studies

In the following section, two ongoing research projects that use the modus operandi as described above are explained. Both projects apply different techniques to do so. One uses a quantitative approach and the other a mixed-method approach. The current conceptual article is based on the two projects and does not directly contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors for which ethical approval was required. An overview of both approaches can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of two approaches to develop and use patient profiles

| Quantitative approach (PROFILe project) | Mixed-method approach (Tailored Healthcare project) | |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | To develop, validate and test patient profiles as an instrument to support more tailored type 2 diabetes management in primary care | To define and validate patient profiles and to test the effect of integrating profiles in healthcare services, materials and systems on total joint replacement patients’ satisfaction with care provision |

| Patient profile development | ||

| Target population | Adult patients with type 2 diabetes treated in primary care | Older adults undergoing lower limb joint replacement surgery |

| Identification of subgroups | Growth mixture modelling | K-means clustering |

| Population size |

~ 10,000 (development cohort) ~ 3000 (validation cohort |

~ 200 (retrospective cohort) ~ 30 (qualitative interviews) |

| Prediction of subgroups | Machine learning | Recursive partitioning |

| Patient profile use in practice | ||

| Assessment: which patient characteristics are assessed? | Body mass index | Coping style |

| Glycated haemoglobin | Anxiety | |

| Triglycerides | Communication preferences | |

| Stratification: how are patients stratified into subgroups? | Healthcare provider enters patients BMI, HbA1c and triglycerides levels into a tool, which enables him/her to view the related subgroup with a similar glycaemic control trajectory | Healthcare provider enters the patient’s scores as determined during the consultation in a decision tree. Alternatively, patients fill out a self-reported questionnaire which is scored according to the decision tree decision rules. A suggestion for the patient’s subgroup is provided along with the level of certainty |

| Tailoring: how is care tailored? | Daily diabetes care planning, lifestyle information, help taking medication, frequency of consultations and emotional support are tailored according to the preferences per subgroup | Preoperative education materials and supportive systems for postoperative (tele)rehabilitation are tailored to the preferences per subgroup |

Patient Profiles: A Quantitative Approach

The Dutch PROFILe (PROFiling patients’ healthcare needs to support Integrated, person-centred models for Long-term disease management) project started in 2014 and is a 4-year public–private research collaboration between a university, hospital, pharmaceutical company and two diabetes care networks (DCNs). PROFILe aims to develop, validate and test patient profiles as an instrument for tailored diabetes management in primary care [17]. The two DCNs both routinely collect patient data. One DCN was considered the development cohort (n = 10,528) and the other the validation cohort (n = 3777).

A quantitative approach was used to develop the patient profiles. In the first step, the longitudinal electronic health records of the development cohort were used to conduct growth mixture modelling [18]. This technique identified three subgroups of patients based on glycaemic control trajectories starting from the point of diagnosis: (1) stable, adequate glycaemic control; (2) improved glycaemic control and (3) deteriorated glycaemic control. Glycaemic control trajectories were chosen as the outcome, because the researchers hypothesized that patients with different glycaemic control trajectories prefer different configurations of diabetes care and support. The identified subgroups were validated in the validation cohort. Second, to explore which phenotypic patient characteristics should be assessed to determine a patient profile and to stratify patients into the right trajectory, machine learning methods were applied. Using the most salient characteristics (baseline body mass index, HbA1c and triglycerides), an algorithm was built to predict the identified glycaemic control trajectories, which was subsequently validated in the validation cohort. The project is currently on the third step, ‘tailoring’: the adaption of care per patient profile. A so-called discrete choice experiment (DCE) is conducted among 300 patients to provide insight into the patients’ preferences for specific configurations of diabetes care and support (e.g. frequency of professional monitoring, involved providers, information provision). These care preferences are paired with the corresponding patient profiles. To diminish heterogeneity within each profile, the influence of psychosocial characteristics, such as self-efficacy and quality of life, on the preferences is also determined.

In the final step of the PROFILe project, a clustered randomized controlled trial will be performed at primary care practices in the Netherlands to assess the perceived benefits, risks and the feasibility of implementing patient profiles as an instrument to safely and successfully provide tailored type 2 diabetes management.

Patient Profiles: A Mixed-Method Approach

The Tailored Healthcare Through Customer Profiling project is a 4-year public–private research collaboration between a hospital, medical device manufacturer, technical university and the creative industry. Its main aims are to define a validated set of design-oriented patient profiles and to test the effect of integrating these profiles in healthcare services (e.g. educational materials and telerehabilitation systems) on satisfaction with care provision following joint replacement surgery.

A mixed-method approach was used to develop the profiles. As a first step, self-reported communication preferences, experiences with pain and stress, self-efficacy, clinical symptoms and surgical outcomes of patients who had underwent joint replacement surgery were assessed. To stratify patients in groups with similar preferences and experiences, k-means cluster analysis was used. The resulting subgroups were validated by comparing the average subgroup characteristics to patients’ actual and ideal hospital experience as expressed in qualitative interviews. To ease classification of future patients into the relevant subgroup by health professionals, recursive partitioning was used to build a decision tree [19]. By asking three questions (which assess active coping skills, experienced helplessness, information needs) either during the consultation or via a self-reported questionnaire, health professionals can quickly stratify future patients to one of the subgroups and deliver care that is better aligned to the patient’s preferences, even when constrained by time.

The final ‘tailoring’ step in this project consists of developing modular variations of existing patient education materials and supportive telerehabilitation systems by design engineers. From their iterative work, it will be determined how preferences should be embedded in tailored design. The envisioned benefit of profile usage (i.e. improved satisfaction) will be examined in a pilot validation of the developed tailored prototypes.

Discussion

The current paper describes two ongoing research projects that develop and use patient profiles to tailor healthcare. Both propose that care can be tailored by the assessment of biopsychosocial patient characteristics, stratification of patients into profiles and tailoring of care in concordance with the common care preferences of these profiles. Patients stratified into a high-risk profile could, for example, receive more intensive disease management, to address their care needs and preferences. Vice versa, more emphasis on self-management could be established for patients of the low-risk profile. It is expected that such tailored approaches will benefit clinical practice by efficiently allocating resources to where they are most needed.

The projects discussed use different methods of profiling, both of which have important advantages and disadvantages. The identification of patient profiles in each approach was carried out in different ways: in the quantitative approach, profiles were identified on the basis of a disease-related health outcome, assuming that patients within a profile share the same preferences for care provision, whereas in the mixed-method approach, profiles were identified on the basis of preferences, assuming that patients within a profile show similar disease-related health outcomes. If these assumptions are not met, additional research might be required to identify separate ‘sub-profiles’ based on preferences for care provision (quantitative approach) or disease-related health outcomes (mixed method approach) within the previously identified profiles.

Thus, future work on patient profiling should carefully specify the intended goal of the patient profiles, as this influences which characteristics should be assessed and consequently which profiles are identified. The different methods of data collection also affect the time, energy and monetary investments required for profile development. The mixed-method approach employed in the Tailored Healthcare project requires less patients to be enrolled in the study which curbs the burden. Therefore, we assume that this approach is more suitable for individual clinics that may serve fewer patients. On the other hand, accurate stratification into subgroups tends to be more reliable in data produced by larger samples, like those used in the quantitative approach of the PROFILe project. These methods may be most suitable for large clinics or multicentre collaborations. Again, we stress the importance of clarifying the goals and expected results of any patient profiling approach in considering these cost and benefits.

Conclusion

The concept of tailored healthcare has been around for centuries. Still, only recently have modern techniques emerged to transform raw data of electronic health records into usable information for care management [20]. Techniques like these (e.g. machine learning, natural language processing [20] and neural network analysis [21]) that enable healthcare professionals and researchers alike to explore new approaches such as patient profiling are described in this paper.

It is expected that patient profiling will result in tailored care. As such, it constitutes a promising method for achieving the so-called triple aim by (1) improving patient experience, by including patients’ care needs and preferences in treatment decisions; (2) improving population health and quality of life, by supporting tailored care and (3) reducing the per capita cost of care, by reducing the overuse, underuse and misuse of healthcare services [22]. Healthcare practitioners who currently provide care to diabetes type 2 or lower limb joint replacement patients can soon use insights from both projects to gain an improved understanding about their patients and to find support in aligning their practice to their patients’ needs. Researchers or clinicians who want to extend the profiling approach to other patient populations should carefully evaluate these expected advantages in relation to their focus and available resources.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Martijn Brouwers, MD, PhD, Arianne Elissen, PhD, Marijke Melles, PhD, Huib de Ridder, PhD, Dirk Ruwaard, PhD and Nicolaas Schaper, MD, PhD for their valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Funding

This work and the article processing charges were supported by Novo Nordisk B.V., the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) (Grant 314-99-118) and Zimmer Biomet Inc. The funding bodies did not play a role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Both authors (Tessa Dekkers and Dorijn F. L. Hertroijs) have nothing to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The current conceptual article is based on the two projects and does not directly contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors for which ethical approval was required.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.6871364.

References

- 1.Dance A. Medical histories. Nature. 2016;537(7619):S52–3. 10.1038/537S52a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prince MJ, Wu F, Guo Y, et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):549–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61347-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364–79. 10.2337/dc12-0413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim J, Davis JW. Prostate cancer screening—time to abandon one-size-fits-all approach? JAMA. 2011;306(24):2717–8. 10.1001/jama.2011.1881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zwijnenberg NC, Damman OC, Spreeuwenberg P, Hendriks M, Rademakers JJ. Different patient subgroup, different ranking? Which quality indicators do patients find important when choosing a hospital for hip- or knee arthroplasty? BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:299. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Netherlands Diabetes Federation. NDF care standard. Transparency and quality of diabetes care for people with diabetes type 2 [NDF Zorgstandaard Transparantie en kwaliteit van diabeteszorg voor mensen met type 2 diabetes]. Amersfoort: Netherlands Diabetes Federation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutch Orthopaedic Association. Guidelines total hip arthroplasty [Richtlijnen Totale heupprothese]. ’s-Hertogenbosch: Dutch Orthopaedic Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elissen AM, Duimel-Peeters IG, Spreeuwenberg C, Spreeuwenberg M, Vrijhoef HJ. Toward tailored disease management for type 2 diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(10):619–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothe U, Muller G, Schwarz PE, et al. Evaluation of a diabetes management system based on practice guidelines, integrated care, and continuous quality management in a federal state of Germany: a population-based approach to health care research. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(5):863–8. 10.2337/dc07-0858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawker GA. Who, when, and why total joint replacement surgery? The patient’s perspective. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18(5):526–30. 10.1097/01.bor.0000240367.62583.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dekkers T, Melles M, Mathijssen NMC, Vehmeijer SBW, de Ridder H. Tailoring the orthopeadic consultation: how perceived patient characteristics influence surgeons’ communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(3):428–38. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseng MM, Wang Y, Jiao RJ. Mass costumization. In: Laperrière L, Reinhart G, editors. CIRP encyclopedia of production engineering. The International Academy for Produ, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2017.

- 13.Sollecito WA. McLauhlin and Kaluzny’s continuous quality improvement. 4th ed. Burlington: Jones & Barlett Learning; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, Fishbein M, Dijkstra A. Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(3):454–66. 10.1093/her/cyn004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Glassman B. One size does not fit all: the case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(4):276–83. 10.1007/BF02895958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noar SM, Harrington NG, Aldrich RS. The role of message tailoring in the development of persuasive health communication messages. Commun Yearb. 2009;33:73–133. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elissen AM, Hertroijs DF, Schaper NC, Vrijhoef HJ, Ruwaard D. Profiling patients’ healthcare needs to support integrated, person-centered models for long-term disease management (PROFILe): research design. Int J Integr Care. 2016;16(2):1. 10.5334/ijic.2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hertroijs DFL, Elissen AMJ, Brouwers M, et al. A risk score including body mass index, glycated haemoglobin and triglycerides predicts future glycaemic control in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(3):681–8. 10.1111/dom.13148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therneau TM, Atkinson EJ. An introduction to recursive partitioning using the RPART routines. Rochester: Division of Biostatistics 61, Mayo Clinic; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halamka JD. Early experiences with big data at an academic medical center. Health Aff. 2014;33(7):1132–8. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller DD, Brown EW. Artificial intelligence in medical practice: the question to the answer? Am J Med. 2018;131(2):129–33. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–69. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.