Abstract

Though research has demonstrated that gay men suffer stress-related mental health disparities compared to heterosexuals, little is known about factors that protect gay individuals from poor mental health and that buffer them in the face of minority stress. Using a daily diary approach, the current study examined three factors that may protect individuals from poor mental health: social support from friends, social support from family, and gay identity. Caucasian gay men (N = 89) completed a study purported to examine the everyday life experiences of gay individuals. Participants completed baseline measures of social support from friends and family, gay identity (i.e., sense of belonging to the gay community), and depression. Participants then completed measures of minority stress and negative affect at the end of each day for 14 consecutive days. Though all three predictors were negatively related to depression at baseline, only friend support remained significant when all predictors were included simultaneously. For the daily data, HLM was used to examine the moderating role that each of the predictors served in the daily minority stress-mental health link. Only friend support moderated the link. Those with more friend support experienced little change in negative affect from average to above-average minority stress days. However, those with less support experienced increases in negative affect from average to above-average minority stress days. The research highlights the importance of friend support for coping, while also suggesting that predictors of minority stress may differ when stress is assessed retrospectively versus daily.

Keywords: Gay Men, Minority Stress, Stress Buffering, Daily Diary

Across the life course, gay men experience mental health disparities in comparison to heterosexual men (Institutes of Medicine, 2011). Data from small convenience samples, meta-analytic reviews, and population-based studies have shown higher prevalence rates for disorders including major depression, anxiety, and panic for gay men in comparison to heterosexual men (Cochran & Mays, 2013; King et al., 2008). At this point, it is well-understood that these mental health disparities are a product of the unique stress experiences faced by sexual minority persons. Included in these stressors are distal stressors (those that occur outside the minority individual) such as overt acts of discrimination, and proximal stressors (those emanating from within the minority individual) such as perceptions of stigma and internalized homophobia (Meyer, 1995, 2003, 2013). Data support the minority stress conceptualization: more exposure to discrimination, perceived stigma, and internalized homophobia are consistently linked with poorer mental and physical health (Fingerhut, Peplau & Gable, 2010; Frost, Lehavot, & Meyer, 2013; Meyer, 1995).

Mental health disparities among gay individuals and the connection between these disparities and minority stress have been well established. At this point, research extending these findings is growing in two key areas. First is research that veers away from reliance on retrospective reports of stress exposure and that instead examines stress processes as they occur (Livingtson, 2017). Second is research identifying factors that protect gay individuals from poor mental health and that moderate links between minority stress and mental health (Hill & Gunderson, 2015; Meyer, 2015). The current study combines these lines of inquiry, using a daily diary methodology to examine the roles that social support and gay identity have in buffering gay individuals from the negative consequences that often accompany exposure to minority stress.

Proximal Assessments of Minority Stress

Critically, most of the research examining minority stress processes has utilized cross-sectional survey designs, and as such has relied on retrospective reports of stress exposure. Recently, researchers have called for use of a more diverse set of methodologies as a way to capture stress experiences and their consequences closer in time to each other (Kwon, 2013; Livingston, 2017). Specifically, Livingston (2017) urged researchers to “increase their use of experience sampling methodologies” (p. 54) or daily diaries.

Daily diaries offer important benefits over cross sectional designs. First, a daily diary methodology better captures processes that are likely sensitive with respect to time (Livingston, 2017). For example, consequences of stress exposure may differ in the short term versus the long term, and daily diaries allow for a cleaner assessment of the more proximal effects. Second, daily diaries likely permit more accurate reporting of the types of stressors that sexual minorities experience. Traditional stress research has made it clear that daily hassles can be as critical as major life events in the stress process (Lazarus, 1990; Suh, Diener, & Fujita, 1996). Although research on minority stress has incorporated assessments of both major life events and daily hassles (diPlacido, 1998), the use of retrospective surveys may bias people to report only major life events or to over-report major life events in comparison to daily hassles. As Swim, Hyers, Cohen, and Ferguson (2001) suggested, minor incidents may be forgotten and therefore not reported in a retrospective survey, though they may have an immediate effect or a cumulative effect over time on mental health. The small window of time between stress exposure and reporting used in the daily diary methodology may permit a more accurate assessment of important, but perhaps less severe, minority stressors. Third, as Swim, Johnston, and Pearson (2009) pointed out, daily diary methodologies not only allow more accurate reporting of stress experiences, but also of affect as well. Specifically, they write that the emotion that may be associated with stress experiences is captured more immediately and thus has less of a chance to dissipate or become distorted with time.

As reported by Livingston (2017), daily diary research with sexual minority samples is currently limited, and only a subset of this work has examined minority stress processes. In this collection are daily diary studies investigating links between: identity disclosure experiences and well-being (Beals, Peplau, & Gable, 2009) and smoking (Pachankis, Westmaas, & Dougherty 2011); minority stress exposure and daily affect (Eldahan, Pachankis, Rendina, Ventuneac, Grov, & Parsons, 2016; Mohr & Sarno, 2016) and distress (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009); and structural stigma and substance use (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, & Starks, 2014). Though mediation is assessed in a couple of studies (Beals, Peplau, & Gable, 2009; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009), moderation and stress buffering are largely ignored (for an exception see Swim, Johnston, & Pearson, 2009). The current research attempts to begin remedying this gap.

Protective Factors in Sexual Minority Mental Health

Despite existing in environments that are stigmatizing, not all gay men suffer from poor mental health or react negatively in the face of minority stress (Cochran & Mays, 2013). What allows for these individuals to evidence such resilience? What factors are associated with better mental health and might protect against the deleterious effects of minority stress exposure for sexual minority individuals? In a broader literature on stress reactivity, myriad factors have been proposed, including rejection sensitivity (Feinstein, Goldfried, & Davila, 2012), locus of control (Carter, Mollen, & Smith, 2013), and self-esteem (Wei, Ku, Russell, Mallinckrodt, & Liao, 2008). The current research examined the protective role of social ties, as these ties have been proposed to have both a main effect on mental health as well as a moderating effect via stress buffering (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001). Two broad types of social ties were considered: ties to individuals (operationalized via social support) and ties to community (operationalized via gay identity).

Social support as a protective mechanism

Social support plays a powerful role in the health of humans. Social support has been associated with better mental health and has even been associated with longevity and increased life expectancy (Berkman & Syme, 1979; Santini, Koyanagi, Tyrovolas, Mason, & Haro, 2015). In addition to these direct links between support and health, social support has also been associated with successful coping in the face of stressors (Cohen, 2004; Cohen & Wills, 1985), perhaps by promoting healthy behaviors in the face of stress and/or by altering and minimizing how a stressor is perceived (Graham & Barnow, 2013).

Research corroborates the positive benefits that social support can provide for sexual minorities. For example, in a sample of lesbian and bisexual women, Lehavot and Simoni (2011) found significant negative correlations between social support and measures of anxiety and depression. Additionally, in a sample of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth, Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, and Malik (2010) showed that increases in social support, in this case specifically related to issues of sexuality, were associated with less psychological distress. Though scholars have proposed that social support may also serve as an important moderator in the link between stress and mental health for sexual minorities (Kwon, 2013), the empirical evidence to date is mixed. In the study by Doty and colleagues (2010), for example, support served as a buffer in the face of sexuality-related stress; specifically, for the LGB youth sampled, in the face of high amounts of sexuality-related stress, those with less support reported more emotional distress than those with more support. In contrast, in a study of gay and bisexual men by Szymanski (2009), links between reports of discrimination and psychological distress did not differ based on participants’ amount of social support. Importantly, the work by Szymanski (2009) operationalized social support as the mean number of individuals a participant could turn to for help in light of six different situations. Thus, the failure to find moderation may reflect the sparse operationalization of the social support construct, which did not account for differences in sources of support (e.g., friend vs. family) nor the degree to which individuals perceived support from the people they listed.

The current work attempted to extend previous research by examining nuances within the social support construct. Specifically, two distinct sources of social support were investigated, namely support from family and support from friends. Though both forms of support have been shown to be important (Procidano & Heller, 1983), friend support may be particularly important for many gay men who often create families of choice due to rejection by families of origin (Weeks, Heaphy, & Donovan, 2001). Corroborating this, Kurdek and Schmitt (1987) found that relationship satisfaction was more closely linked to support from friends than family for same-sex couples but that the opposite was true for different-sex couples. Additionally, Frost, Meyer, and Schwartz (2016) found that gay men were more likely than heterosexual men and women to rely on other LGB individuals (presumably friends) more than family members for social support.

With all this in mind, for the current study, it was predicted that social support (regardless of source) would be positively related to mental health and that social support would buffer individuals on days when they experienced above-average minority stress. Additionally, it was predicted that support from friends would be more impactful than that from family for a sample of sexual minority men.

Gay identity as a protective mechanism

Consistently, studies of sexual minority individuals have demonstrated a positive association between gay identity and mental health. Frable, Wortman, and Joseph (1997), for example, found that sexual minority men who felt more positive about being gay fared better in terms of mental health. In a sample of lesbian women, Fingerhut, Peplau, and Ghavami (2005) showed that lesbian identity was significantly and positively correlated with life satisfaction. Similarly, in a sample of gay men and lesbian women, increases in LGB identity were associated with significant decreases in depressive symptoms (Fingerhut, Peplau, & Gable, 2010).

The current research sought to replicate these findings. Specifically, it was predicted that gay identity would be positively associated with mental health. Furthermore, the current study sought to extend these findings by examining the moderating role that gay identity might serve. Research focused on minority groups other than sexual minorities supports the idea that identity can serve a protective function in the stress process. Landrine and Klonoff (1997) found that the link between sexist events and distress attenuated for those women who identified as feminist. Similarly, Neblett, Shelton, and Sellers (2004) showed that identity centrality buffered against the negative effects of racial hassles in a sample of African Americans. More specifically, participants who held their African American identity as a central part of the self experienced similar well-being regardless of whether they experienced race-related minority stress or not; in contrast, those lower in identity centrality experienced significantly poorer well-being in the face of minority stress than not.

To date, research examining the stress buffering properties of identity in samples of sexual minority individuals is quite limited. Fingerhut, Peplau, and Gable (2010) found that gay identity, assessed as a sense of belonging to the LGB community, moderated links between perceived stigma and depressive symptoms for gay men and lesbians. More recently, in a sample of sexual minority women, Mason, Lewis, Winstead, and Derlega (2015) showed that gay identity, assessed via a measure of collective self-esteem, moderated links between external heterosexism and internalized heterosexism. Specifically, for those women lower in positivity about being part of the LGB community, increases in harassment and discrimination were associated with increases in internalized homophobia. In contrast, for those women higher in positivity about their sexual minority identity, links between discrimination and internalized homophobia did not exist. Interestingly, a daily diary study by Swim, Johnston, and Pearson (2009) challenges the stress buffering role of gay identity. In this seven day diary study, participants completed measures of minority stress, well-being, and identity each day. Results not only failed to support the stress buffering hypothesis, but in fact contradicted it. Specifically, those who were high in gay identity showed decreases in well-being in the face of minority stress. Importantly, however, gay identity was measured each day as opposed to at a single time point and in this way likely covaried with experiences of heterosexism and well-being. In the current study, in contrast, gay identity was treated as a trait or disposition and was measured at a single time point, before the diary portion of the study even began. It was predicted that, in contrast to those lower in gay identity, those higher in gay identity would be buffered in the face of stress and would not experience mental health decrements on days when minority stress was above average.

Method

Participants

Because ethnicity and gender likely affect the life experiences of gay and lesbian individuals and because this study relied on data from a small sample, only Caucasian gay men living in the United States were sampled. Based on sample size data from a diary study assessing reactivity to daily stress (Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995), 100 men who self-identified as both Caucasian and gay participated in an online daily diary study concerning sexual orientation and daily life experiences in exchange for $25. Eleven men were removed from analyses. Of these, five failed to complete any daily entries, five only completed one daily entry, and one did not complete the key measures assessed at baseline.

Of the 89 remaining participants, they ranged in age from 19–65 (M = 36.78, SD = 12.18). The participants in this sample were highly educated: 34% had an advanced degree and only 3% had no college experience. The sample was recruited online, and, as such, participants came from across the United States. The top five represented states are as follows: California (N = 16), Illinois (N = 14), Florida (N = 10), North Carolina (N = 7), and Michigan (N = 5).

Procedure

Calls for participation were emailed to a variety of organizations and to individuals who participated in other studies of gay individuals conducted by the researcher. In an attempt to reach a broad spectrum of gay men, some who were more connected to the LGB community than others, an array of organizations was sampled. For example, in addition to contacting large LGB centers in major US cities, coming out support groups in small cities and even online were contacted and asked to pass the call for participation to members. Because the call was sent widely, it is not known which organizations actually sent the information to their members or not. However, as part of an intake survey that participants completed, they were asked to indicate how they heard about the study, which sheds some light on where participants came from. Approximately 40% of participants (N = 37) listed the above organizations as the source for recruitment; 21 heard about the study from an email sent directly by the researcher; 11 stated that they heard about the study from a friend; 17 stated they heard about it from email but did not specify from where the email came; and 3 participants stated that they did not remember.

Participation occurred in two phases, both online. In the first phase, an intake session, participants completed a variety of baseline measures assessing demographics, social support, gay identity, and mental health. Participants also reviewed instructions on how to complete the daily diary measures. As part of the instructions, participants read operational definitions of three minority stressors. Discrimination was described as “acts of disapproval, rejection, verbal criticism or violence related to being gay.” Perceived stigma was described as “the perception or belief that you may be rejected, ostracized, or discriminated against because you are gay. Perceived stigma can involve situations where you feel awkward or uncomfortable because of your sexual orientation or worry that you may be treated badly.” Finally, internalized homophobia (which was called “sexual orientation conflict”) was described as “discomfort with or disapproval of one's own sexual orientation.” In addition to these definitions, participants were presented with a range of examples for each stressor. To insure comprehension of these operationalizations, participants were asked to write about an experience that either they or a friend had with each of the three stressors. If it seemed that a participant was confused, the researcher emailed the participant to clarify the definitions.1

In the second phase, the daily report phase, participants completed a brief online survey at the end of each day for 14 consecutive days. The survey began with questions about daily mental health. Next, participants rated the extent to which they experienced each of the three minority stressors during the day. To insure compliance across the 14 days, participants were sent daily email reminders. Additionally, if participants failed to complete a nightly entry, they were told that they could complete the entry first thing in the morning. Specifically participants were told: “If you forget to complete a form at the end of the day it is OK to complete it first thing the next morning. If you do this, only report on events that happened the previous day.” After completing seven entries, participants were sent a congratulatory message, thanking them for completing half of the study and encouraging them to continue with the second half.

At the completion of the study, participants were asked to provide their name and mailing address so that $25 could be sent to them. Participants who wished to remain anonymous were given the option to donate their $25 to a charity of their choosing. In these cases, participants were asked to provide the name and address of the charity. All procedures and materials were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Materials

Baseline

As part of the initial session, participants completed basic demographic information (e.g., age, sexual orientation label) as well as measures of social support, gay identity, and baseline mental health. To assess social support, participants completed eight items from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Procidano & Heller, 1983), with four items assessing support from family and four items assessing support from friends. Participants used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) to rate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with such statements as “My family really tries to help me” and “I can count on my friends when things go wrong” and “I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows.” Responses to both subscales were reliable (family support: α = .89, M = 3.24, SD = 1.09; friend support: α = .89, M = 4.13, SD = .75).

To assess gay identity, items from the Multi Ethnic Identity Measure (Phinney, 1992; Roberts, et al., 1999) were adapted to assess connection to the LGB community. Specifically, participants used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) to rate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with four items adapted from the Affirmation/Belonging subscale: “I am happy that I am a member of the gay, lesbian, bisexual community;” “I have a strong sense of belonging to the gay, lesbian, bisexual community;” “I have a strong attachment toward gay, lesbian, bisexual people;” “I feel good about being in the gay, lesbian, bisexual community.” Scores on these items proved highly reliable (α = .84, M = 3.97, SD = .73).

To assess baseline mental health, participants completed the widely-used Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Using a response scale ranging from 1 (rarely; less than 1 day) to 4 (most or all of the time; 5–7 days), participants rated how often during the past week they experienced a variety of feelings or symptoms. Examples include “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me” and “I didn’t feel like eating; I had a poor appetite” and “I felt afraid.” The alpha in this sample was .93 (M = 1.63, SD = .58).

Daily measures

Each daily entry was comprised of two sections. First, participants completed a measure of daily mental health. Specifically, negative affect was assessed. Negative affect was chosen given its role as a component of both anxiety and depression (Clark & Watson, 1991; Eldahan, et al., 2016), mental health disorders that are more prevalent in gay versus heterosexual men (Cochran & Mays, 2013). The 10-item Negative Affect Scale (Watson, Tellegen, & Clark, 1988) was used to measure daily negative affect. Using a 1–5 scale (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely), participants indicated the extent to which they had experienced emotions such as “ashamed” and “nervous.” Using aggregate data averaging each participant’s responses across the days they participated in the study, the responses to this scale were highly coherent (α = .95, M = 1.53, SD = .46).

Second, participants completed a measure of daily exposure to the three minority stressors. Participants rated on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all; 7 = a lot) the extent to which they experienced discrimination, internalized homophobia, and perceived stigma. More specifically, each day participants responded to three prompts stating the following: “Today to what extent did you experience discrimination [sexual orientation conflict, perceived stigma] based on your sexual orientation?” Measured at the daily level, average levels for each of the three minority stressors were low: for discrimination, M = 1.07, SD = .24; for internalized homophobia, M = 1.27, SD = .62; and for perceived stigma, M = 1.39, SD = .60. As a result, rather than examine each of the stressors separately, an indicator of daily minority stress was computed by averaging participant’s responses to these three items. Though this was not what was originally planned, it is in line with previously published diary research by Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, and Dovidio (2009), who used a measure of minority stress that similarly collapsed across multiple types of sexual minority stressors. Again, using aggregate data, reliability was assessed and was more than acceptable (α = .74, M = 1.25, SD = .42).

Results

The results section is divided into two parts. In the first part, data from the baseline measures are examined using linear regression in order to investigate direct associations between friend support, family support, and gay identity, on one hand, and mental health as assessed by the CESD, on the other hand. In the second part, multilevel modeling and a daily assessment of mental health (as opposed to a baseline assessment) are used to examine direct associations between the key constructs as well as the moderating role that friend support, family support, and gay identity play in the link between daily minority stress exposure and daily mental health.

Baseline Data

Table 1 presents the correlations among the key constructs. In line with prediction, support from family, support from friends, and gay identity were all negatively correlated with depression. Linear regression was used to examine the unique contributions of each of the predictor variables on depression. Importantly, when all three predictors were included in the same model, only friend support significantly predicted depression, R2 = .31, FΔ (3, 84) = 12.57, p <.000; βfriend support = −.45, p < .000, βfamily support = −.12, p = .23, βgay identity = −.10, p = .32.

Table 1.

Correlations among Key Variables at Baseline

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression | - | |||

| 2. Friend Support | −.54** | - | ||

| 3. Family Support | −.35** | .44** | - | |

| 4. Gay Identity | −.27* | .31** | .25* | - |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Daily Diary Data

To begin, 74 daily diary entries were discarded because the participant completed more than one entry in a single sitting, filled an entry out within six hours of the previous entry, or took longer than two hours to complete the entry. This left 1,108 valid entries to be used in the analyses. For the 89 men who completed at least two daily entries, the mean number of valid diaries completed was 12.45 (SD = 3.28; Range: 2–17). Approximately 63% of participants completed at least 14 daily diaries.

To examine direct main effects as well as moderating effects, a two-level multilevel model was used in which the lower level included days and the upper level included persons. In other words, the lower level contained the daily measures of negative affect and minority stress exposure, and the upper level contained the person-level variables of friend support, family support, and gay identity.

Using Hierarchical Linear Modeling, here is the equation examining associations between support from friends and daily negative affect as well as the moderating role of support from friends on the link between minority stress and negative affect:

The coefficients at level 1 (within persons) are modeled at level 2 (between persons). For example, β0j, which reflects a participant’s average negative affect across the days in the study, is determined by: γ00 or average negative affect for participants at the mean on the support variable; γ01 or the coefficient quantifying the effect that friend support has on negative affect; and U0j or error. β1j, the coefficient quantifying the effect that minority stress has on negative affect for a particular person, is determined by: γ10, the association between minority stress and negative affect for the average person; and γ11 or the coefficient representing the effect that friend support has on the relationship between minority stress and negative affect. Given these equations, the analyses examined the associations between each of the three moderating variables and negative affect on days when a participant experienced average versus above-average minority stress for himself. In all cases, the moderating variable (i.e., family support, friend support, gay identity) was entered as a z-scored variable in order to aid interpretation of the coefficients. Furthermore, at the upper level, the random component of the intercept was allowed to vary and the random component of the slope was fixed.

As with the baseline data, increases in friend support were associated with decreases in daily negative affect, t(87) = −2.93, p = .004; γ01 = −.16. Increases in family support were similarly associated with decreases in daily negative affect, t(87) = −2.19, p = .031; γ01 = −.11. In contrast to prediction and baseline data, gay identity was not significantly related to mental health at the daily level, t(87) = −.79, p = .433; γ01 = −.04. Finally, as was found with the baseline data, when all three predictors were included simultaneously, only friend support significantly predicted daily negative affect, t(85) = −2.34, p = .021; γ01friend support = −.14 (for family support, t(85) = −.91, p = .365, γ01family support = −.05; and for gay identity, t(85) = .31, p = .76; γ01gay identity = .02).

Before examining the moderating role of each predictor, a model was run examining the direct association between daily minority stress, which was centered around each participant’s mean, and daily negative affect. In line with minority stress theory and previous cross sectional research, increases in stress exposure were associated with more negative affect. Specifically, on days when participants experienced minority stress above their own average, they reported significantly more negative affect, t(1016) = 3.74, p < .000; γ10 = .19.

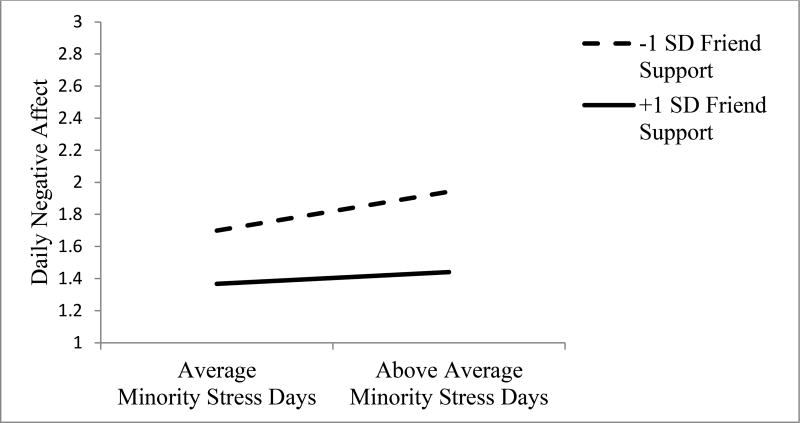

Table 2 presents the coefficients for each of the three analyses run. Of the three moderating variables, only friend support moderated the relationship between stress and negative affect, t(1015) = −2.55, p = .011; γ11 = −.08. Using analyses and calculation tools provided by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006), simple slopes were examined. The significance of the slope relating negative affect and minority stress was examined at one standard deviation below and above the mean of the moderator variable, support from friends. As seen in Figure 1, for those lower in friend support, the slope relating negative affect and stress exposure was significant, demonstrating that as stress exposure increased, negative affect increased, t(1015) = 4.33, p < .000; γ11 = .24. In contrast, for those higher in friend support, the slope relating negative affect and stress exposure was not significant, t(1015) = 1.34, p = .181; γ11 = .07. Thus, in line with the stress buffering hypothesis, those higher in friend support did not experience increases in negative affect with increased exposure to stress.

Table 2.

Final Estimation of Fixed Effects (with Robust Standard Errors) Predicting Daily Negative Affect

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | SE | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For intercept | |||||

| Intercept (γ00) | 1.53 | .05 | 33.32 | 87 | .000 |

| Friend Support (γ01) | −.16 | .06 | −2.93 | 87 | .004 |

| For Slope | |||||

| Minority Stress (γ10) | .16 | .04 | 3.54 | 1015 | .000 |

| Friend Support (γ11) | −.08 | .03 | −2.55 | 1015 | .011 |

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | SE | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For intercept | |||||

| Intercept (γ00) | 1.53 | .05 | 32.31 | 87 | .000 |

| Family Support (γ01) | −.11 | .05 | −2.19 | 87 | .031 |

| For Slope | |||||

| Minority Stress (γ10) | .18 | .05 | 3.89 | 1015 | .000 |

| Family Support (γ11) | −.04 | .05 | –.91 | 1015 | .366 |

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | SE | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For intercept | |||||

| Intercept (γ00) | 1.53 | .05 | 31.47 | 87 | .000 |

| Gay Identity (γ01) | −.04 | .05 | –.79 | 87 | .433 |

| For Slope | |||||

| Minority Stress (γ10) | .19 | .05 | 3.93 | 1015 | .000 |

| Gay Identity (γ11) | .01 | .06 | .11 | 1015 | .914 |

Figure 1.

Support from friends moderating the link between minority stress exposure and daily negative affect

Discussion

Despite evidence that gay men suffer from mental health disparities, many are incredibly resilient and thrive in the face of stigmatization. The current study sought to examine the roles that social support from friends and family as well as gay identity play in the lives of sexual minority men. Adding to a growing body of daily diary studies, the current study utilized a daily diary approach, thereby producing cross sectional data from baseline measures as well as short-term longitudinal data across 14 days of assessments. At baseline, results confirmed what previous cross sectional research has revealed: gay identity and social support are associated with more positive outcomes for sexual minority individuals. Additionally, these data revealed that support from friends may be the most beneficial of the three constructs assessed.

The data from the daily diary component of the study are consistent with prediction and past research in some ways but not in others. Social support, in both forms assessed, was negatively related to daily negative affect. Furthermore, support from friends buffered individuals in the face of stress. The fact that individuals high in friend support experienced little change in negative affect from average stress days to above-average stress days may reflect a floor effect. In general, these individuals scored very low in negative affect, which may reflect the positive benefits that social support can have on the everyday lives of individuals. That individuals lower in friend support experienced more negative affect on high stress days potentially demonstrates the consequences of lacking like-minded others to turn to in the face of stress. Without a sounding board, these individuals may not have had an outlet to be affirmed with regards to their sexual orientation and their personhood. It could also be the case that increased minority stress combined with an awareness that one is lacking in social support leads to self-doubt and ultimately to more negative affect. Though family support was linked directly with daily negative affect, it did not serve a moderating function. Perhaps this should not come as a surprise given what is known about the relative importance of friend support over family support for LGB individuals, particular for gay men (Frost, Meyer, & Schwartz, 2016).

Surprisingly, gay identity did not predict affect at the daily level, demonstrating that identity might work differently on a global level as opposed to a day-to-day level. Additionally, gay identity did not moderate links between stress and mental health at the daily level. This corroborates what Swim, Johnston, and Pearson (2009) found in their diary study in a sample of sexual minority individuals, this time using a baseline measure of gay identity as opposed to a composite of daily assessments of identity. Some research with ethnic minorities has also revealed a similar pattern. Specifically, Arbona and Jimenez (2013) found that ethnic identity did not moderate the link between minority stress and depression in a sample of ethnic minority college students. Overall, the data from the current study suggest that gay identity serves a limited role and one that may not be activated in the short term.

Though this study adds to growing bodies of research examining stress buffering and using diary methodologies, it contains several limitations that should be addressed in future research. To begin, constructs such as gay identity and social support are multifaceted and were operationalized in narrow ways at this nascent stage of the research. For example, social identity as discussed by Roberts, et al. (1999) includes two independent components: Exploration, which involves active participation in one’s social group as well as an understanding of the role that identity plays in one’s life, and Affirmation and Belonging, which involves attachment to one’s social group. The current research only examined Affirmation and Belonging, though Exploration may be differently and perhaps more related to the outcomes of interest (Abdou & Fingerhut, 2014). Future research should utilize a more expanded operationalization of identity and should tap multiple conceptualizations of social identity such as those laid out by Roberts, et al. (1999) and Sellers and colleagues (e.g., Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998), as well as an assessment of involvement in minority community activities. Similarly, operationalizations of social support should be broadened. Social support contains various components, including distinctions between perceptions of support versus actual receipt of support, as well as distinctions between tangible support versus emotional support. The current research did not account for such differences, and future research would benefit from doing so.

Future daily diary research would also benefit from a more detailed examination of the three minority stressors assessed. Given the burden of completing daily assessments, participants were asked very broad questions about exposure to discrimination, perceived stigma, and internalized homophobia. As such, the nuance of what these experiences looked like was lost. Additionally, because participants reported experiencing few of the stressors in the limited timeframe of the study, all the stressors were combined to form a minority stress composite; the distinctions among the stressors were therefore blurred. In Meyer’s (1995) original test of the minority stress model, each of the three stressors uniquely predicted the outcomes of interest. Given this, more fine grained assessments of the stressors over a longer period of time (e.g., 30 days) are needed in future studies as a way to potentially insure sufficient exposure to each stressor so that each could be examined independently.

Another clear limitation of the research concerns the sample used. As mentioned, sexual minorities are not a monolithic group and vary based on gender and ethnicity as well as other socio-demographic variables. Given the powerful role that such constructs have in the lives of individuals and the small sample size that was used in this study, participation was limited based on gender and ethnicity. Future research must examine the effects of identity intersectionality in the minority stress process of LGB individuals.

Despite these limitations, the current study makes important contributions to our understanding of the minority stress process for sexual minority individuals. First, the current research highlights the potentially important role that social support from friends has in the lives of sexual minorities. Across all analyses, friend support emerged as the strongest predictor of mental health and resilience. Those interested in interventions meant to alleviate the detrimental consequences of minority stress may benefit from focusing on sexual minority individual’s social networks and on the bonds that these individuals form with close peers. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the novel methodology sheds light on distinctions that need to be made between retrospective accounts of stress and mental health and more proximal assessments of such constructs. The fact that patterns in the baseline data were not fully replicated in the diary data provides the possibility that stress processes might work differently over the long term as they do on a day-to-day basis. Of course, more research is needed to establish this more clearly and to better understand links among various constructs at multiple temporal levels.

Public Significance Statement.

The current research highlights the potentially important role that social support from friends has in the lives of gay men. Across all analyses, friend support, in contrast to support from family or a sense of belonging to the gay community, emerged as the strongest predictor of mental health and resilience. Additionally, links between variables at baseline were not fully replicated in a daily diary study, suggesting that distinctions might need to be made between retrospective accounts of stress and mental health and more proximal assessments of such constructs. Results suggest that researchers and practitioners need to be mindful moving forward that stress processes might work differently over the long term as they do on a day-to-day basis.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible through several grants: an NIMH sponsored NRSA Predoctoral Fellowship, a SPSSI Grant-in-Aid Award, and a Dissertation Year Fellowship provided by the Graduate Division and UCLA.

The author thanks Letitia Anne Peplau, Shelly L. Gable, Paul G. Davies, Eric Vilain, Hector Myers, and Christia Spears Brown for helpful comments throughout the research process. The author thanks David M. Frost for comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This occurred on less than 5 occasions. The vast majority of participants were able to provide examples that coincided with the operational definitions.

References

- Abdou CM, Fingerhut AW. Stereotype threat among Black and White women in health care settings. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;20:316–323. doi: 10.1037/a0036946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbona C, Jimenez C. Minority stress, ethnic identity, and depression among Latino/a college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;61:162–168. doi: 10.1037/a0034914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals KP, Peplau LA, Gable SL. Stigma management and well-being: The role of social support, cognitive processing, and suppression. Personality and Social. Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:867–879. doi: 10.1177/0146167209334783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year followup study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1979;109:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:890–902. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter LW, II, Mollen D, Smith NG. Locus of control, minority stress, and psychological distress among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2014;61:169–175. doi: 10.1037/a0034593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Sexual orientation and mental health. In: Patterson CJ, D'Augelli AR, editors. Handbook of psychology and sexual orientation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 204–222. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist. 2004;59:676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- diPlacido J. Minority stress among lesbians, gay men and bisexuals. In: Herek GM, editor. Stigma and Sexual Orientation. Vol. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 138–159. [Google Scholar]

- Doty N, Willoughby BB, Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:1134–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldahan AI, Pachankis JE, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. Daily minority stress and affect among gay and bisexual men: A 30-day diary study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;190:828–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Goldfried MR, Davila J. The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: an examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:917–927. doi: 10.1037/a0029425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerhut AW, Peplau LA, Gable SL. Identity, minority stress and mental health among gay men and lesbians. Psychology and Sexuality. 2010;1:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerhut AW, Peplau LA, Ghavami N. A dual-identity framework for understanding lesbian experience. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Frable DES, Wortman C, Joseph J. Predicting self-esteem, well-being, and distress in a cohort of gay men: The importance of cultural stigma, personal visibility, community networks, and positive identity. Journal of Personality. 1997;65:599–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Lehavot K, Meyer IH. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9523-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH, Schwartz S. Social support networks among diverse sexual minority populations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86:91–102. doi: 10.1037/ort0000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JM, Barnow ZB. Stress and social support in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual couples: Direct effects and buffering models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:569–578. doi: 10.1037/a0033420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CA, Gunderson CJ. Resilience of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in relation to social environment, personal characteristics, and emotion regulation strategies. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2:232–252. [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78:458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai S, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA, Schmitt J. Perceived emotional support from family and friends in members of homosexual, married, and heterosexual cohabiting couples. Journal of Homosexuality. 1987;14:57–68. doi: 10.1300/J082v14n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon P. Resilience in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Personality and Social. Psychology Review. 2013;17:371–383. doi: 10.1177/1088868313490248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. Discrimination against women: Prevalence, consequences, remedies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Theory-based stress measurement. Psychological Inquiry. 1990;1:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Simoni JM. The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:159–170. doi: 10.1037/a0022839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston NA. Avenues for future minority stress and substance use research among sexual and gender minority populations. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2017;11:52–62. doi: 10.1080/15538605.2017.1273164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason T, Lewis RJ, Winstead B, Derlega VJ. External and internalized heterosexism among sexual minority women: The moderating roles of social constraints and collective self-esteem. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2:313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress and mental health in lesbian, gay and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2013;1:3–26. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2:209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, Sarno EL. The ups and downs of being lesbian, gay, and bisexual: A daily experience perspective on minority stress and support processes. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2016;63:106–118. doi: 10.1037/cou0000125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Shelton J, Sellers RM. The role of racial identity in managing daily racial hassles. In: Philogène G, editor. Racial identity in context: The legacy of Kenneth B. Clark. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 77–90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Starks TJ. The influence of structural stigma and rejection sensitivity on young sexual minority men's daily tobacco and alcohol use. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;103:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Westmaas JL, Dougherty LR. The influence of sexual orientation and masculinity on young men’s tobacco smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:142–152. doi: 10.1037/a0022917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7:156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Santini ZI, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S, Mason C, Haro JM. The association between social relationships and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;175:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton J, Rowley SJ, Chavous TM. Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh E, Diener E, Fujita F. Events and subjective well-being: Only recent events matter. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1091–1102. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.5.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swim JK, Hyers LL, Cohen LL, Ferguson MJ. Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Swim JK, Johnston K, Pearson NB. Daily experiences with heterosexism: Relations between heterosexist hassles and psychological well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2009;28:597–629. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM. Examining potential moderators of the link between heterosexist events and gay and bisexual men’s psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks J, Heaphy B, Donovan C. Same Sex Intimacies: Families of Choice and other Life Experiments. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Ku T, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, Liao KYH. Moderating effects of three coping strategies and self-esteem on perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms: A minority stress model for Asian international students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:451–462. doi: 10.1037/a0012511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]