Abstract

Emotion regulation deficits may link stigma to poor mental health, yet existing studies rely on self-reported stigma and do not consider contextual factors. In the present research, we examined associations among cultural stigma (i.e., objective devaluation of others’ status), emotion regulation deficits, and poor mental health. In Study 1, we created an index of cultural stigma by asking members of the general public and stigma experts to indicate desired social distance towards 93 stigmatized attributes. In Study 2, emotion regulation deficits mediated the association between cultural stigma and adverse mental health outcomes, including depressive symptoms and alcohol use problems, among individuals endorsing diverse stigmatized identities. The indirect effect of cultural stigma, via emotion regulation, on these outcomes was stronger among those reporting more life stress. These findings highlight the adverse impact of cultural stigma on mental health and its role in potentiating stigmatized individuals’ susceptibility to general life stress.

Defined as characteristics that are devalued in a particular social context (Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998), stigma encompasses a wide range of identities (e.g., racial/ethnic minority status, minority sexual orientation), personal attributes (e.g., physical appearance, old age), and physical/mental health conditions (e.g., HIV, depression). Across a large number of studies, stigma has been shown to undermine the mental health of a substantial segment of the general population through a host of shared mechanisms, such as limited access to structural resources as well as maladaptive psychological and behavioral responses (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013). One such mechanism that has received significant empirical attention is emotion regulation deficits (i.e., the inability to monitor, evaluate, and modulate one's emotional reactions; Thompson, 2008), which has been shown to mediate the association between stigma-related experiences (e.g., perceived discrimination and internalized stigma) and adverse mental health outcomes (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Miranda, Polanco-Roman, Tsypes, & Valderrama, 2013; Pachankis, Rendina, et al., 2015; Rendina et al., 2016).

Across studies of stigma, emotion regulation, and mental health, stigma is typically conceptualized as subjective, self-reported experiences from the targets’ perspective. However, this approach is limited given the known confounds between self-reports of perceived stigma and mental health status, such that individuals who experience greater deficits in emotion regulation might perceive more stigma-related experiences as a result of these difficulties (Contrada et al., 2000; Lilienfeld, 2017). Scant research has examined whether more objective forms of stigma that do not rely on stigmatized individuals self-reporting their experiences might drive emotion regulation deficits and poor mental health. To this end, the present research examined the role of emotion regulation deficits as a mechanism underlying the association between an objective index of cultural stigma (i.e., the extent to which a stigmatized identity is culturally devalued by members of the general public; Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009) and adverse mental health outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms and alcohol use problems) among individuals with a wide range of stigmatized characteristics.

Stigma, Emotion Regulation, and Mental Health

Chronic exposure to stigma-related stress can deplete self-regulatory resources, thereby undermining individuals' ability to understand and manage their emotions (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Inzlicht, McKay, & Aronson, 2006). Across several studies among both racial/ethnic and sexual minorities, rumination, a putatively maladaptive emotion regulation strategy that involves passively and repetitively focusing on one's problems and their causes, mediated the association between stigma-related experiences and internalizing mental health symptoms, such as depression and anxiety (Hatzenbuehler, Dovidio, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Phills, 2009; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009; Miranda et al., 2013). Other deficits in emotion regulation (e.g., lower emotional awareness and acceptance, limited access to various emotion regulation strategies, difficulty with engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing negative emotions) have also been found to mediate the association between sexual minority stigma and depressive symptoms among gay and bisexual men (Pachankis, Rendina, Restar, Ventuneac, Grov, & Parsons, 2015). Similar results were obtained with other stigmatized groups, including those who are HIV-positive (Rendina et al., 2016) and overweight (Douglas & Varnado-Sullivan, 2016).

Although less research has directly examined the role of emotion regulation as a mechanism underlying the association between stigma and alcohol use problems, existing evidence implicates its mediating role. In particular, Gibbons and colleagues (2012) found that self-control (i.e., a set of related abilities that includes focusing and shifting attention, delaying gratification, and inhibiting impulsive behaviors) mediated the association between perceived racial discrimination and alcohol use among African American adolescents. Consistent with these findings, emotion regulation deficits are increasingly recognized as a predictor of healthrisk behaviors, such as alcohol and recreational drug use, in the general population. Specifically, numerous studies have shown that individuals who experience greater emotion regulation difficulties are more inclined to engage in substance use as a means to avoid negative emotional states that they are unable to tolerate or accept (Dvorak et al., 2014; Paulus et al., 2016; see Weiss, Sullivan, & Tull, 2015, for a review).

Despite these converging lines of evidence that situate emotion regulation as a crucial mechanism linking stigma and mental health, no research, to our knowledge, has examined how contextual factors, such as general life stress (i.e., chronic stressors that are not directly attributable to prejudice and discrimination), may influence its association with mental health outcomes among stigmatized groups. This paucity of data is particularly noteworthy given the relevance of contextual risk factors for the identification and tailoring of appropriate interventions for stigmatized individuals at the greatest risk of developing psychiatric disorders (Reid, Dovidio, Ballester, & Johnson, 2014). Recent studies on emotion regulation outside the stigma literature have repeatedly painted emotion regulation’s association with psychological adjustment as being contextually dependent (for reviews, see Aldao, 2013; Bonanno & Burton, 2013). In particular, behavioral assessments of emotion regulation demonstrate that individuals who are less adept at engaging in effective emotion regulation (e.g., cognitive reappraisal, flexible expression and suppression of emotions) tend to be especially vulnerable to poor mental health in the context of high stress (Troy, Wilhelm, Shallcross, & Mauss, 2010; Westphal, Seivert, & Bonanno, 2010). Thus, it is possible that individuals whose emotion regulation abilities are compromised by stigma would also be more susceptible to the adverse mental health when facing greater levels of general life stress.

Moving Beyond the Individual: The Role of Cultural Stigma

Although psychological research has largely conceptualized stigma as an intrapersonal, private phenomenon, it is important to note that stigma, by definition, is culturally constructed independently of the stigmatized targets themselves, and is dependent upon social, economic, and political power (Link & Phelan, 2001). Indeed, among individuals with a wide range of concealable stigmatized identities in one study, cultural stigma, which was independently assessed by asking a separate sample of participants to rate how negatively each stigma is typically viewed, was associated with both psychological distress and physical illness symptoms among the stigmatized even after accounting for their perceived stigma (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). Similarly, another study linked negative attitudes towards people with HIV/AIDS to elevated disclosure concerns among an independent sample of HIV-positive individuals residing in the same communities as those who provided the attitudinal ratings (Miller, Grover, Bunn, & Solomon, 2011). Taken together, these studies highlight that stigmatizing attitudes expressed by the general public, when assessed independently from the stigmatized person’s perceptions, can adversely impact the health and well-being of stigmatized individuals.”

The Present Research

In light of these findings, the present research addresses whether cultural stigma would drive emotion regulation deficits and adverse mental health outcomes. Controlling for the stigmatized person’s self-reported perceived stigma would adjust for known confounds between self-reported stigma experiences and mental health and therefore produced less biased estimates of this association. In order to examine this research question among individuals with a wide range of stigmatized characteristics, we first created an index of cultural stigma by asking both stigma experts and members of the general public to provide social distance ratings for each of the 93 stigmatized identities, conditions, and characteristics (Study 1). Subsequently, utilizing a sample of individuals who possess diverse stigmatized identities, we examined the possibility that cultural stigma would, via its effects on emotion regulation deficits, be linked to adverse mental health outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms, alcohol use problems), even when controlling for individual experiences of perceived stigma; we also assessed whether general life stress (i.e., non-stigma-related stress) would strengthen the indirect effect of emotion regulation on the association between cultural stigma and mental health (Study 2).

Study 1

Data for this study were taken from a larger project examining the overall impact of stigma on individual well-being (Pachankis et al., in press). Study 1 had two objectives: (1) identify a list of stigmatized identities, conditions, and characteristics that represent a comprehensive spectrum of the stigma experience in the general population, following the approach used in the larger project; and (2) derive an index of cultural stigma for each of the identified stigmatized attributes. Drawing from previous research that assessed negative public attitudes towards stigmatized groups (e.g., Crandall & Moriarty, 1995; Link, Yang, Phelan, & Collins, 2004), we chose social distance as a measure of the extent to which each stigma is culturally devalued. To maximize the objectivity of our index, we obtained these social distance ratings from two vantage points. First, we asked stigma experts to rate their perceived social distance of the general population towards each of the stigmatized attributes. Second, we asked members of the general public to rate their own desired social distance towards each of the stigmatized attributes.

Method Participants

Expert raters

To guide recruitment of this subsample, we defined an “expert” as an individual who had published at least one highly cited academic paper pertaining to stigma. We conducted a literature search using both Social Science Citation Index and Google Scholar to identify these persons, which resulted in a list of 197 stigma experts. Of these experts, 64 began the survey and 53 completed at least 85% of the survey data. The final analytic sample included those 64 experts who submitted at least partial data, but rater agreement calculations, which could only be performed using complete data, were limited to the 53 experts who submitted at least 85% of the data. We imputed the 5% of the data that were missing from this sample overall using the sample mean for each respective item. Respondents were primarily psychologists (49.1%), sociologists (22.6%), psychiatrists (9.4%), and epidemiologists (5.7%). A small percentage of the sample had backgrounds in anthropology, nursing, social work, communications, and economics.

General public raters

We recruited non-expert raters from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Two-hundred and sixteen participants were initially recruited, but we removed 20 participants who submitted partial responses and three who failed a data quality check (e.g., selected the first option for every response). The final analytic sample consisted of 193 participants, the majority of which were White (86.5%), female (57%), employed full-time (61.1%), and residents of 39 U.S. states.

Measures

List of stigmatized identities

Following the approach used in the parent study (Pachankis et al., in press), to ensure the inclusion of a wide range of stigmatized statuses, we broadly define stigma as any socially devalued attribute or characteristic “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (Crocker et al., 1998; Goffman, 1963). Drawing from searches of academic databases (i.e., PubMed, PsycInfo, Google Scholar), seminal works in stigma research (e.g., Jones et al., 1984), discussions among members of our research team, and feedback from a group of 25 students enrolled in a graduate seminar on stigma, we created a list of 93 stigmatized identities, health conditions, and personal attributes.

Cultural stigma

We assessed the extent to which each stigmatized characteristic was culturally devalued using the seven-item Social Distance Scale (Link, Cullen, Frank, & Wozniak, 1987). For each of the 93 stigmas, raters indicated willingness to interact in various ways with people who possess each stigma (i.e., as a co-worker, as a neighbor, as a tenant, as a child caretaker, as a potential daughter/son-in-law, as a social acquaintance, and as a prospective job-seeker). Specifically, experts were asked to rate the items in terms of their understanding of general social perceptions (α=.84); members of the general public were asked to rate the items based on their own personally held attitudes (α=.83). Each item was rated on a four-point scale, ranging from 0 (definitely unwilling) to 3 (definitely willing).

Results and Discussion

Cultural stigma scores were calculated in two steps. In the first step, which was done separately for the general public and stigma expert samples, we computed mean social distance ratings for each stigmatized characteristic. In the second step, we combined the average social distance ratings for the expert and general public subsamples for each stigmatized characteristic. To test the appropriateness of combining both expert and general public’s ratings of cultural stigma into a single score, we calculated the correlation between the two for each stigma. Given the high correlation between the two samples (r=0.97, p<.001), we combined them to arrive at one cultural stigma rating for each of the 93 stigmas.

Our cultural stigma index contributes to the existing literature on stigma, emotion regulation, and mental health in two important ways. First, as noted earlier, self-reports of stigma-related experiences are likely to be influenced by the mental health and emotion regulation abilities of the stigmatized individuals who make such reports (Contrada et al., 2000; Lillenfeld, 2017). Relying on an indicator of cultural stigma, independent from the self-reported perceptions of the stigmatized individuals themselves, would therefore enable us to draw stronger conclusions on the causal links among stigma exposure, emotion regulation deficits, and poor mental health. Second, with few exceptions (e.g., Douglas & Varnado-Sullivan, 2016; Rendina et al., 2016), nearly all existing studies on stigma and emotion regulation have focused on sexual and racial/ethnic minorities. As such, additional research is needed to assess the generalizability of the emotion regulation mediation model to individuals with a wider range of stigmatized attributes. By generating cultural stigma indices for 93 stigmatized characteristics, the current study provides a valuable tool for investigating the links among cultural stigma, emotion regulation deficits, and adverse mental health outcomes across a more diverse range of stigmas than heretofore examined. We turn to this research aim in Study 2.

Study 2

In Study 2, we examined the links among cultural stigma, emotion regulation deficits, and adverse mental health outcomes within a sample of individuals who possess a wide range of stigmatized attributes. Participants first indicated all of the stigmatized attributes they possessed by selecting from the list of 93 characteristics identified in Study 1; those who endorsed more than one stigmatized attribute were asked to rank these attributes based on their personal impact. Participants then completed a series of questionnaires, including those assessing perceived stigma associated with their most impactful stigmatized attribute, exposure to general life stress, emotion regulation deficits, depressive symptoms, and alcohol use problems. Each participant was assigned a cultural stigma score (derived from Study 1) based on their most impactful stigmatized attribute.

Consistent with previous research linking self-reported stigma to poor mental health through deficits in emotion regulation (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, 2009), we hypothesized that cultural stigma would also be significantly associated with depressive symptoms and alcohol use problems, with emotion regulation deficits mediating these associations. We further hypothesized that these associations would remain significant after accounting for individual’s self-reported experiences of perceived stigma. Additionally, we explored whether the indirect effect of cultural stigma on mental health via emotion regulation would be moderated by exposure to general life stress. Given that stigmatized individuals, such as racial/ethnic and sexual minorities, tend to experience greater general life stress (e.g., financial and relationship problems) than their non-stigmatized counterparts (Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008), clarifying the potential role of general life stress in modifying the stigma-emotion regulation-mental health pathway represents an important area of inquiry. Given that stress has been shown to moderate the association between emotion regulation and mental health (Troy et al., 2010; Westphal et al., 2010), we hypothesized that exposure to elevated general life stress would exacerbate the adverse impact of stigma on mental health through emotion regulation by moderating the second half of the emotion regulation pathway connecting stigma to mental health (i.e., individuals with greater emotion regulation deficits would report worse mental health when exposed to higher levels of general life stress).

Methods

Participants

A total of 1,123 individuals were recruited for the study via MTurk. Of these, we omitted individuals who did not complete all demographic variables (n=50) and/or outcome variables (n=65). The final analytic sample, consisting of 1,025 participants, was equally comprised of both genders (45.5% female), and was, on average, 38.6 years of age (SD=11.28). The majority of participants were White (79.5%); a smaller proportion was Asian/Pacific Islander (10.3%), Black (5.5%), or reported any other race or combination of races (4.7%). Approximately 8.1% of the sample identified as being of Hispanic ethnicity. The majority of the sample reported at least some college-level education (86.4%) and being employed full-time (58.5%).

Measures

Cultural stigma

At the beginning of the survey, participants were provided with the list of 93 possible stigmas identified in Study 1 and asked to indicate which of the stigmas applied to them. On the next page, participants received the following instructions: “Below is a list of the conditions that you previously selected as being applicable to you. Please review the list and rank-order the conditions based on the degree to which each condition influences your life OR how significant or important it is to your life.” We considered each participant’s top-ranking stigma as his/her most personally impactful stigma and used it as the basis for assigning each participant a cultural stigma score (e.g., a participant who identified “being Black/African American” as her most personally impactful stigma would receive the cultural stigma score associated with “being Black/African American” derived in Study 1). Participants who did not select any of the 93 stigmatized identities (n=46) received a cultural stigma score of 0.

Emotion regulation deficits

Participants’ emotion regulation ability was measured with the Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004). The DERS assesses self-reported difficulty across six emotion regulation ability domains: acceptance of emotions (e.g., “When I’m upset, I become embarrassed for feeling that way”), engaging in goal-directed behavior (e.g. “When I’m upset, I have difficulty focusing on other things”), controlling emotional impulses (e.g., I experience my emotions as overwhelming and out of control”), emotional awareness (e.g., “I am attentive to my feelings,” reverse coded), access to emotion regulation strategies (e.g., “When I’m upset, I believe wallowing in it is all I can do”), and emotional clarity (e.g., “I have difficulty making sense of my feelings”). Items were ranked on a five-point scale, with possible responses ranging from 1 (almost never [0–10%]) to 5 (almost always [91–100%]). The scale evidenced adequate internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s α=0.91).

General life stress

We measured participants’ exposure to general life stress using the 36-item Chronic Strains Scale (Turner & Avison, 2003). Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they have experienced a variety of stressors (e.g., “Your work is boring and repetitive”) on a three-point scale. Possible responses included 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true), and 2 (very true).

Depressive symptoms

We assessed participants’ depressive symptoms in the past week using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Participants indicated frequency of occurrence of depressive symptoms (e.g., “My sleep was restless”) over 20 items using a four-point scale, ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time [less than 1 day]) to 3 (most or all of the time [5–7 days]). The scale evidenced adequate internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s α=0.92).

Alcohol use problems

Participants’ problems with alcohol use were assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993), a 10-item screening inventory used to identify hazardous drinking. Items were rated on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (daily or almost daily) with qualitative anchors depending on the item (e.g., “How often during the last 3 months have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking?”). Cronbach’s α was 0.90 in the current sample.

Perceived stigma

Participants’ perceptions of their stigma exposure was measured with the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997), which assesses the frequency by which individuals experience nine types of interpersonal mistreatment as a result of possessing their most impactful stigma. Participants rated each item (e.g., “People act like they think they are better than you”) along a six-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (almost every day). Cronbach’s α in the current sample was 0.92.

Data analysis

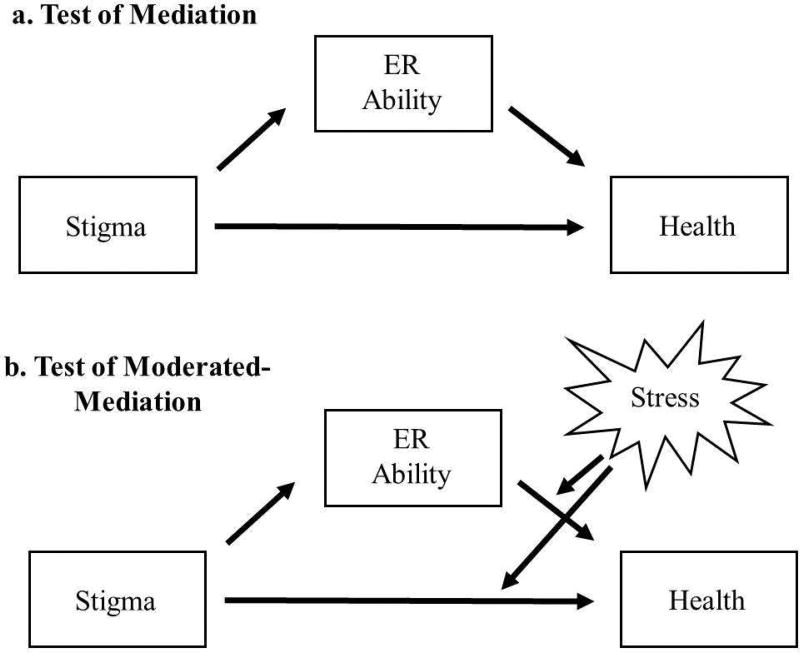

Data were analyzed across two phases. In the first phase (Figure 1, Panel A), we examined the hypothesis that emotion regulation deficits would mediate the association between cultural stigma and poor mental health by testing two simple mediation models, with depressive symptoms and alcohol use problems as respective dependent variables. In the second phase of the analysis, we tested whether general life stress would strengthen the indirect effect of emotion regulation on the association between cultural stigma and mental health. Specifically, we entered general life stress as a moderator on the b and c pathways, thereby testing its interaction with the direct effect of cultural stigma on mental health, as well as the indirect effect in which emotion regulation deficits predict mental health. Finally, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses by repeating all of the tested models while controlling for perceived stigma. All analyses were conducted using the SPSS PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2012). These analyses employed bootstrapping (5,000 iterations) to create a 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect. The independent, mediating, and moderating variables were standardized prior to analysis to facilitate data interpretation.

Figure 1.

Models of Emotion Regulation Mediating Stigma and Mental Health

Results

Do emotion regulation deficits mediate the association between cultural stigma and mental health?

Emotion regulation deficits mediate the association between stigma and depression

Cultural stigma was positively associated with both emotion regulation deficits (b=.15, p<.001, CI:.09, .21) and depressive symptoms (b=.65, p<.001, CI:.32, .97). Emotion regulation deficits were also positively associated with depressive symptoms (b=5.51, p<.001, CI:5.18, 5.84). The direct effect of cultural stigma on depressive symptoms was significant (b=.65, p<.001, CI:.32, .97). The indirect effect of cultural stigma on depressive symptoms via emotion regulation deficits was also significant (b=.82, CI:.46, 1.17).

Emotion regulation deficits mediate the association between stigma and alcohol use problems

Cultural stigma was positively associated with alcohol use problems (b=.87, p< .001, CI:.50, 1.22). Emotion regulation deficits were also positively associated with alcohol use problems (b=1.36, p<.001, CI:1.00, 1.73). The direct effect of cultural stigma on alcohol use problems via emotion regulation deficits was significant (b=.87, CI:.50, 1.23), as was the indirect effect (b=.20, CI:.10, .33).

Does general life stress moderate the association between cultural stigma and poor mental health through emotion regulation deficits?

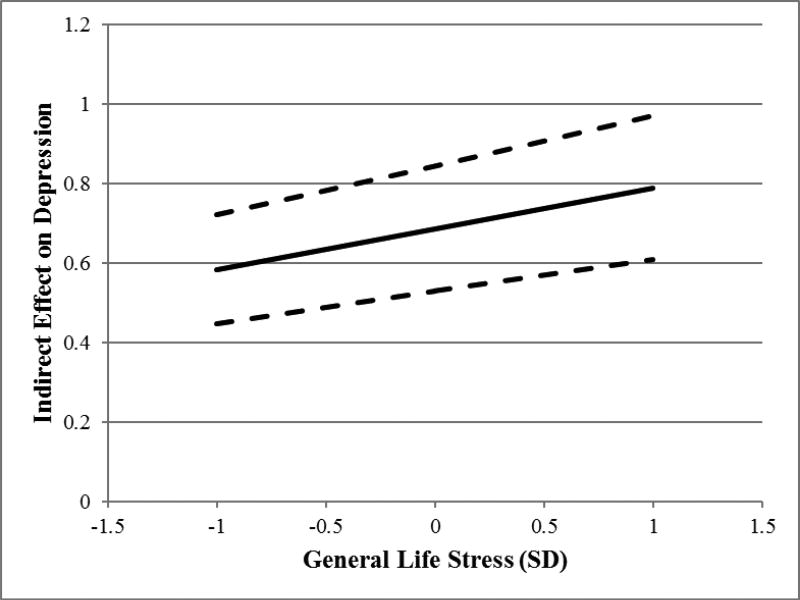

Stress exacerbates the indirect effect of emotion regulation on the association between cultural stigma and depressive symptoms

General life stress was positively associated with depressive symptoms (b=1.97, p<.001, CI:1.59, 2.34). Additionally, it moderated the direct effect of cultural stigma on depressive symptoms (b=.52, p<.001, CI:.22, .81), such that the positive direct effect of stigma on depressive symptoms was stronger for those who had higher levels of general life stress than those with lower levels of general life stress. General life stress also moderated the indirect effect of stigma on depressive symptoms (b=.66, p<.001, CI:.37, .95). The index of moderated-mediation was significant, indicating that the indirect effect from cultural stigma to depressive symptoms, via emotion regulation deficits, was stronger among persons reporting higher levels of general life stress than persons reporting lower levels of general life stress (b=.10, CI:.04, .17; Figure 2).

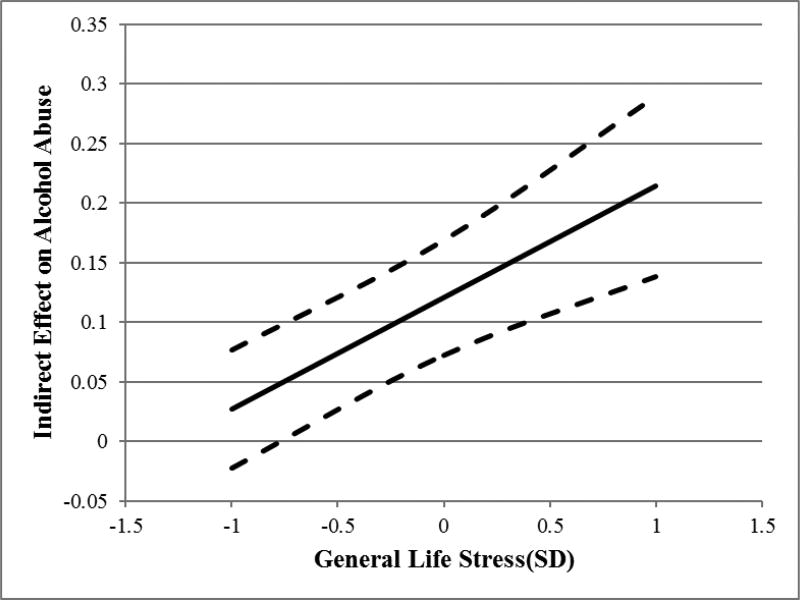

Figure 2.

Conditional Indirect Effects of Cultural Stigma on Mental Health Symptoms, via Emotion Regulation, as a Function of General Life Stress

Stress exacerbates the indirect effect of emotion regulation on the association between cultural stigma and alcohol use problems

General life stress was positively associated with alcohol use problems (b=.75, p=.001, CI:.30, 1.20). Stress levels did not significantly moderate the direct effect of cultural stigma on alcohol use problems (b=.13, p=.46, CI: −.22, .49). However, stress levels did moderate the indirect effect of stigma on alcohol use problems (b=.59, p<.001, CI:.25, .92). The index of moderated-mediation was significant, indicating that the indirect effect from cultural stigma to alcohol use problems, via emotion regulation deficits, was stronger among persons reporting higher levels of general life stress than persons reporting lower levels of general life stress (b=.09, CI:.03, .19; Figure 2).

Controlling for perceived stigma

We repeated each of the above analyses controlling for each participant’s self-reported perceptions of stigma. Participants who did not report possessing any stigmas (n=46) did not complete the perceived stigma measure, and thus were omitted from these analyses. When controlling for perceived stigma for emotion regulation’s indirect effect between cultural stigma and mental health, emotion regulation remained as a significant mediator in the models predicting depressive symptoms (b=.63, CI:.32, .98), and alcohol use problems (b=.12, CI:.05, .23). Tests of moderated mediation, controlling for perceived stigma, revealed that general life stress remained a significant moderator of the indirect effect between cultural stigma and both depressive symptoms (b=.10, CI:.05, .17) and alcohol use problems (b=.09, CI:.02, .18) via emotion regulation.

Discussion

Using an objective index of cultural stigma, a more comprehensive array of stigmas than previously examined, and measures of general life stress, the present study provides novel evidence that stigma acts as a pervasive determinant of emotion regulation deficits and poor mental health. Specifically, we demonstrated that emotion regulation deficits significantly mediated the association between cultural stigma and adverse mental health outcomes, including depressive symptoms and alcohol use problems. Moreover, general life stress significantly moderated this mediation pathway, such that the indirect effect of stigma on both depressive symptoms and alcohol use problems through emotion regulation deficits was stronger among persons experiencing higher levels of general life stress; in other words, persons facing greater levels of cultural stigma appeared to become more sensitized to the adverse mental health impact of general life stress. Notably, these pathways remained significant even when controlling for participants’ own perceptions of stigma exposure, highlighting the value of considering objectively-measured cultural stigma as a predictor of emotion regulation deficits and poor mental health.

General Discussion

Across two studies, the present investigation examined the associations between cultural stigma, emotion regulation deficits, and adverse mental health outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms, alcohol use problems) among individuals endorsing diverse stigmatized attributes. In Study 1, we created an index of cultural stigma for each of the 93 stigmatized characteristics by collecting social distance ratings from both stigma experts and members of the general public. In Study 2, we applied this cultural stigma index to test the emotion regulation pathway connecting cultural stigma to mental health, and explored the role of general life stress as a potential moderator of this pathway. We showed that cultural stigma significantly predicted emotion regulation deficits and poor mental health over-and-above participants’ self-reported perceived stigma. We further demonstrated that exposure to high levels of general life stress exacerbated the emotion regulation pathway connecting cultural stigma to mental health, such that individuals who experienced greater levels of cultural stigma were more susceptible to the adverse mental health impact of general life stress due to emotion regulation deficits.

Taken together, these studies advance prior research by introducing a novel objective measure of stigma for a wide range of identities, health conditions, and personal attributes that represent a comprehensive spectrum of the stigma experience in the general population. They also significantly extend prior research on stigma, emotion regulation, and mental health by examining the associations among these constructs across a large number of stigmatized groups and by considering how these associations might vary as a function of exposure to general life stress, an important, yet largely under-studied, contextual factor. In light of recent interest in contextual influences on emotion regulation processes (Aldao, 2013; Bonanno & Burton, 2013) and empirical attention to potential confounds between self-reported stigma perceptions and mental health status (Lillenfeld, 2017), the present research represents a significant methodological and theoretical contribution to both the stigma and emotion regulation literatures.

In one prominent psychological mediation framework of stigma, which posits that psychological characteristics like emotion regulation are the primary avenues by which stigma influences mental health, Hatzenbuehler (2009) called for examination of moderators of this pathway to “provide important information regarding individual vulnerabilities to stress, general psychological processes and the development of psychopathology.” Our test of general life stress as a moderator provides the first evidence, to our knowledge, that stigma and its associated mechanisms do in fact increase vulnerabilities to stress. The implications of this finding are significant, as it suggests that stigmatized individuals face a disadvantage not only due to facing stigma-related stressors that less-stigmatized individuals do not face, but that stigmatized individuals may also be less capable of emotionally adjusting to even stressors not directly related to stigma. Health disparity researchers who work with stigmatized groups that face greater levels of day-to-day stress may thus find emotion regulation to be a particularly relevant determinant of mental health outcomes among these populations.

The current findings also have practical implications for intervention research efforts to address stigma-related mental health disparities. While efforts to reduce cultural stigma itself are often impractical given stigma’s pervasive sociological function and causes (Link & Phelan, 2001), cultural stigma’s influence on emotion regulation presents a modifiable individual treatment target. To this end, clinical interventions that seek to facilitate effective emotion regulation in the context of coping with stigma-related stress have gained initial traction in improving the mental health of certain stigmatized groups, including sexual minorities (Burton, Wang, & Pachankis, in press; Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, et al., 2015) and people with mental illnesses (Luoma, Kohlenberg, Hayes, Bunting, & Rye, 2009). Future research could productively examine how these interventions might be adapted to address the mental health needs of a broader range of stigmatized populations and the interactive effect between stigma-related and general life stress.

The present investigation has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of our data preclude predictive, causal conclusions. Given that shifts in cultural stigma take place over the span of decades rather than months or years, attempts to chart its longitudinal associations with mental health outcomes over time will likely present significant logistical challenges. As such, we believe that a cross-sectional design represents a reasonable starting point for investigating the mental health impact of cultural stigma, especially considering that our results are bolstered by evidence from both experimental and daily diary studies connecting other forms of stigma with emotion regulation and mental health (Hatzenbuehler, Dovidio, et al., 2009; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, et al., 2009; Johns, Inzlicht, & Schmader, 2008).

Second, consistent with previous research assessing the impact of cultural stigma on psychological well-being (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009), we opted to derive cultural stigma scores for Study 2 participants based only on their most personally impactful stigmatized identity. However, we recognize that most individuals possess multiple stigmatized attributes and that these attributes often interact to uniquely shape their stigma-related experiences and mental health (Cole, 2009). Future research could explore potential quantitative solutions, such as aggregating the cultural stigma ratings associated with all stigmatized characteristics possessed by each participant (Pachankis et al., in press), to better account for the reality of intersectionality faced by many stigmatized individuals.

Another notable limitation was our use of the DERS to measure emotion regulation. The DERS possesses significant overlap with personality facets like neuroticism, but nonetheless incrementally predicts mental health outcomes when controlling for such personality traits (Stanton, Rozek, Stasik-O’Brien, Ellickson-Larew, & Watson, 2016). In a series of sensitivity analyses in Study 2, we attempted to statistically account for the potential self-report bias of the DERS by controlling for self-reported perceived stigma, which has also been shown to share strong overlap with neuroticism (Huebner et al., 2005). Though we did not directly measure neuroticism in our current study, the continued magnitude and direction of our estimates while controlling for self-reported stigma allays some concern that self-report bias of negative events, rather than emotion regulation itself, might drive the association between public stigma and mental health. Previous evidence also suggests that self-reported emotion regulation predicts performance in lab-based behavioral assessments of emotion regulation ability (Burton & Bonanno, 2016), thereby lending greater validity to self-reports of emotion regulation. Still, future studies examining how stigma might compromise emotion regulation ability would benefit from including behavioral assessments of multiple emotion regulation types, such as reappraisal (McRae, Jacobs, Ray, John, & Gross, 2012) and expressive suppression (Westphal, Seivert, & Bonanno, 2010), as these would provide greater validity and clarity to the specific ways in which stigma might impair emotion regulation abilities.

In summary, the present research introduces a novel, objective measure of cultural stigma, which we then utilized to assess the associations between stigma, emotion regulation deficits, and adverse mental health outcomes among individuals endorsing a wide range of stigmatized attributes. Findings underscore the value of considering cultural devaluation (in addition to targets’ own stigma perceptions) and contextual factors (e.g., general life stress) when assessing the impact of stigma on mental health. They also highlight the role of emotion regulation as a promising treatment target for clinical interventions that seek to reduce stigma-related mental health disparities.

Acknowledgments

Charles Burton was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH020031; Trace Kershaw, Principal Investigator). Katie Wang was also supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH109413-01-S1; John Pachankis, Principal Investigator). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the research team: Forrest W. Crawford, Adam I. Eldahan, Mark L. Hatzenbuehler, Bruce G. Link, Hannah Mogul-Adlin, and Jo C. Phelan.

References

- Aldao A. The future of emotion regulation research: Capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(2):155–172. doi: 10.1177/1745691612459518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Burton CL. Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(6):591–612. doi: 10.1177/1745691613504116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton CL, Bonanno GA. Measuring ability to enhance and suppress emotional expression: The Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression (FREE) Scale. Psychological Assessment. 2016;28(8):929–941. doi: 10.1037/pas0000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton CL, Wang K, Pachankis JE. Psychotherapy for the spectrum of sexual minority stress: Application and technique of the ESTEEM treatment model. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.05.001. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, Gary ML, Coups E, Egeth JD, Sewell A, Chasse V. Ethnicity-Related Sources of Stress and Their Effects on Well-Being. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9(4):136–139. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8721.00078. [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64(3):170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall CS, Moriarty D. Physical illness stigma and social rejection. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1995;34(1):67–83. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert D, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. 4. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas V, Varnado-Sullivan P. Weight stigmatization, internalization, and eating disorder symptoms: The role of emotion dysregulation. Stigma and Health. 2016;1(3):166–175. doi: 10.1037/sah0000029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Sargent EM, Kilwein TM, Stevenson BL, Kuvaas NJ, Williams TJ. Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences: associations with emotion regulation difficulties. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40(2):125–130. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.877920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, O’Hara RE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng C-Y, Wills TA. The erosive effects of racism: Reduced self-control mediates the relation between perceived racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(5):1089–1104. doi: 10.1037/a0027404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on a spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26(1):41–54. JOUR. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(5):707–30. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Dovidio JF, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Phills CE. An implicit measure of anti-gay attitudes: Prospective associations with emotion regulation strategies and psychological distress. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(6):1316–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(12):1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How Does Stigma “Get Under the Skin”? Psychological Science. 2009;20(10):1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Population Health Inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling [White paper] 2012 Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Huebner DM, Nemeroff CJ, Davis MC. Do hostility and neuroticism confound associations between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24(5):723–740. [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, McKay L, Aronson J. Stigma as ego depletion. Psychological Science. 2006;17(3):262–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns M, Inzlicht M, Schmader T. Stereotype threat and executive resource depletion: Examining the influence of emotion regulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2008;137(4):691–705. doi: 10.1037/a0013834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE, Farina A, Hastorf AH, Markus H, Miller DT, Scott RA. Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. Microaggressions: Strong claims, inadequate evidence. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2017;12(1):138–169. doi: 10.1177/1745691616659391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF. The social rejection of former mental patients: Understanding why labels matter. American Journal of Sociology. 1987;92(6):1461–1500. doi: 10.1086/228672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27(1):363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, Collins PY. Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30(3):511–541. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Bunting K, Rye AK. Reducing self-stigma in substance abuse through acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, manual development, and pilot outcomes. Addiction Research & Theory. 2009;16:149–165. doi: 10.1080/16066350701850295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae K, Jacobs SE, Ray RD, John OP, Gross JJ. Individual differences in reappraisal ability: Links to reappraisal frequency, well-being, and cognitive control. Journal of Research in Personality. 2012;46(1):2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Polanco-Roman L, Tsypes A, Valderrama J. Perceived discrimination, ruminative subtypes, and risk for depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19(4):395–403. doi: 10.1037/a0033504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Grover KW, Bunn JY, Solomon SE. Community norms about suppression of AIDS-related prejudice and perceptions of stigma by people with HIV or AIDS. Psychological science. 2011;22(5):579–583. doi: 10.1177/0956797611404898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina HJ, Safren SA, Parsons JT. LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(5):875–889. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Rendina HJ, Restar A, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. A minority stress—emotion regulation model of sexual compulsivity among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Health Psychology. 2015;34(8):829–840. doi: 10.1037/hea0000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Wang K, Burton CL, Crawford FW, Phelan JC, Link BG. The burden of stigma on population health: A multidimensional taxonomy of stigmas. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. doi: 10.1177/0146167217741313. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus DJ, Bakhshaie J, Lemaire C, Garza M, Ochoa-Perez M, Valdivieso J, Zvolensky MJ. Negative affectivity and problematic alcohol use among Latinos in primary care: The role of emotion dysregulation. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2016;12(2):137–147. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2016.1172897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: the impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97(4):634–651. doi: 10.1037/a0015815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. JOUR. [Google Scholar]

- Reid AE, Dovidio JF, Ballester E, Johnson BT. HIV prevention interventions to reduce sexual risk for African Americans: The influence of community-level stigma and psychological processes. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;103:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina HJ, Gamarel KE, Pachankis JE, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. Extending the minority stress model to incorporate HIV-positive gay and bisexual men’s experiences: A longitudinal examination of mental health and sexual risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9822-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton K, Rozek DC, Stasik-O’Brien SM, Ellickson-Larew S, Watson D. A transdiagnostic approach to examining the incremental predictive power of emotion regulation and basic personality dimensions. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2016;125(7):960. doi: 10.1037/abn0000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of a definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2008;59(2–3):25–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy AS, Wilhelm FH, Shallcross AJ, Mauss IB. Seeing the silver lining: Cognitive reappraisal ability moderates the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms. Emotion. 2010;10(6):783–795. doi: 10.1037/a0020262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Avison WR. Status variations in stress exposure: Implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(4):488. doi: 10.2307/1519795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Sullivan TP, Tull MT. Explicating the role of emotion dysregulation in risky behaviors: A review and synthesis of the literature with directions for future research and clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;3:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal M, Seivert NH, Bonanno GA. Expressive flexibility. Emotion. 2010;10(1):92. doi: 10.1037/a0018420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]