Abstract

This paper examines the housing and service interventions that work best to end family homelessness and to promote housing stability, adult and child well-being, family and self-sufficiency in the United States. It is based on the short-term (20-month) results of the Family Options Study, which recruited 2,282 families in emergency homeless shelters across 12 sites and randomized them to one of three housing and service interventions or to usual care in their communities. The approaches test both theoretical propositions about the nature of family homelessness and practical efforts to end it. Permanent housing subsidies were most successful at ending homelessness and promoting housing stability and had radiating impacts on all the other domains, suggesting that homelessness among families in the United States is centrally a problem of housing affordability. Project-based transitional housing, which attempts to address families’ psychosocial needs in supervised settings, and temporary ‘rapid re-housing’ subsidies had little effect.

Keywords: Family homelessness, Family Options Study, housing affordability

Introduction

What kind of housing and service interventions work best to end homelessness for families? The Family Options study is a large-scale experiment that provides some answers to that question for families in the United States. Before describing the different approaches used in the study and the theories behind them, it is helpful to say something about ways that the social context of homelessness among families in the United States differs from parallel contexts in Europe.

The U.S. Context of Family Homelessness

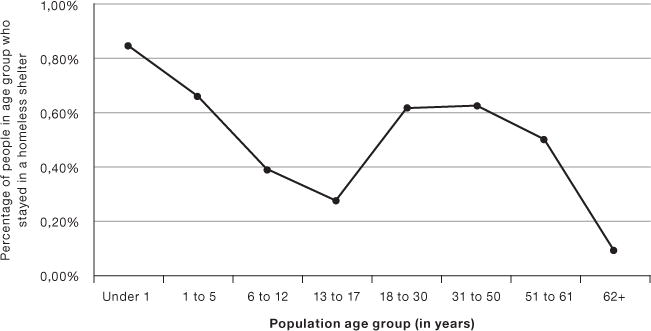

Families constitute a larger portion of people who become homeless in the United States than in most European countries. According to the Annual Homelessness Assessment Report to Congress (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2015), over a third of people who are homeless at a given time in the United States are homeless with their families. Families with young children are at special risk, arguably because the United States spends much less on safety net programmes (Smeeding, 2005; Jusko, 2016) and on assistance to families in particular (Gornick and Jäntti, 2012;2016) than does Europe. Indeed, although more adults than children experience homelessness, a person in the United States is most likely to spend a night in a homeless assistance programme during infancy (see Figure 1). Rates of homelessness remain high during the preschool years and fall off when children enter school, probably because parents must pay for most preschool programmes but what Americans call ‘public school’ is free. Rates of stays in homeless programmes then rise again in early adulthood, at which point some of the affected adults are the parents of young children. Rates remain high throughout middle age, although not as high as for young children, before falling off for older adults.

Figure 1. Homelessness by Age Group in the United States (annual estimates).

Sources: Population by age group calculated by authors from U.S. Census Bureau (2014) Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013. Numbers experiencing an emergency shelter stay by age obtained from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2014) Demographic Characteristics of Sheltered Homeless Persons by Household Type, October 2012 – 2013. HMIS Estimates from the 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress.

Another important contextual fact is that there is no State in the United States where a full-time worker who works year round at the minimum wage (federal minimum or state minimum where that is higher) can afford the Fair Market Rent for even a one-bedroom apartment (National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2015). The Fair Market Rent is a low-average rent, set at the 40th percentile for units coming onto the market in the geographic locale. Affordability is defined here by the federal standard that households should spend no more than 30 percent of their pre-tax income on housing. Among the seven jurisdictions where the largest numbers of families experience homelessness, the number of hours a person would have to work at the local minimum wage in order to afford a two-bedroom apartment (suitable for a small family) ranges from 115 hours per week in Seattle (on the West Coast) to 151 hours per week in Nassau/Suffolk (outside New York City).2 The United States is thus a country in which large numbers of poor families are potentially vulnerable to homelessness.

Interventions under Study

The Family Options study compared three housing and service interventions to one another and to usual care in twelve sites in the United States. The interventions have different conceptual rationales, and proponents make different predictions about their relative effects.

The first intervention was permanent housing subsidies, typically provided by vouchers, which enabled families to rent market-rate housing from private landlords, paying only 30 percent of their income for rent: the voucher paid the rest. That is, the central intervention was to make housing affordable. Some families got help with finding housing but no other assistance from the homeless service system.

They were, of course, free to find and use whatever additional services were generally available in their communities. The theory behind permanent subsidies is that homelessness for families in the United States is primarily a problem of housing affordability, a problem that vouchers can solve. Stabilizing families in housing removes a major stressor from their lives, allows more family income to be spent on goods other than housing, and provides a platform on which families can build to address any other problems on their own. Proponents thus expect subsidies to reduce homelessness and other measures of residential instability, and perhaps to have salutary impacts in the four other domains we studied: adult well-being, family preservation, child well-being and self-sufficiency. A previous experiment found that giving housing vouchers to poor families receiving public assistance (welfare) prevented homelessness (Wood et al., 2008), and quasi-experimental work has shown that housing subsidies can prevent homelessness (Shinn, 1992), end it (Culhane, 1992; Wong et al., 1997; Zlotnick et al., 1999), and promote residential stability (Shinn et al., 1998).

Housing subsidies are not part of the usual homeless service system; there are long waiting lists in most communities, and many fewer subsidies available than eligible households. We arranged with the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development to provide incentives to local Public Housing Authorities that control subsidies to make them available to the study. This infusion of resources made participation in the study attractive to both families and service providers in participating communities.

The second approach, called community-based rapid re-housing, offered short-term housing subsidies lasting up to a potential 18 months, though lasting typically less than half that time in practice. Again, families used the subsidies, which were structured differently in different communities, to rent in the private rental market. Families had to be re-certified (typically on the basis of both income and progress on a case plan) every three months for continued receipt of subsidies. Participants also received low-intensity case management that focused on housing and employment. The rationale for rapid re-housing is that in tight housing markets, various events can push poor families into homelessness. The central role of the homeless service system is to help families resolve the immediate crisis and get back into ordinary housing as quickly as possible, with the lightest touch necessary, so as to offer help efficiently to the largest number of families. Proponents’ predictions are much the same as for permanent subsidies, with a focus on reduced use of the homeless service system.

Rapid re-housing is a relatively new approach in the United States. Although it has received a good deal of interest, advocacy and funding, as yet there has been little rigorous empirical research. Of the veterans with families that received rapid re-housing services, 9.4 percent had a repeat episode of homelessness recorded in the veteran system in the first year and 15.5 percent had a repeat episode by the end of the second year after exiting from rapid re-housing services; rates were lower for families than for adults without children, but there was no comparison made with households that received other services (Byrne et al., 2016). Summarizing several unpublished studies, Cunningham et al. (2015) reported that returns to homelessness for households (sometimes including single adults) that received rapid re-housing were generally low, but that residential instability was often high. Without well-matched comparison groups it is hard to know what would have happened had households received other interventions.

The third approach was project-based transitional housing – temporary housing lasting up to two years in a supervised facility with other homeless families, combined with intensive case management. Case managers assessed families’ needs at programme entry, and either provided or arranged for the provision of services to address those needs. The theory behind transitional housing is that families who experience homelessness are experiencing a number of challenges – from a lack of job skills or poor credit to substance dependence and domestic violence – that they need to address in order to lay the foundation for later housing stability. Thus, transitional housing is a housing readiness rather than a housing first approach. To differentiate transitional housing from rapid re-housing, we excluded programmes called ‘transition in place’ that place families in scattered units where they can take over the lease at the end of the programme. Proponents expect transitional housing to improve adult well-being and family self-sufficiency, which in turn should reduce homelessness and improve additional outcomes, such as family preservation and child well-being. Previous studies of transitional housing often describe the successes of programme graduates (Northwest Institute for Children and Families, 2007; Burt, 2010) without any comparison group or reference to others who left before graduation. As for rapid re-housing, it is difficult to know what would have happened had families been offered other interventions.

We compared these options to usual care in participating communities. From a research-design perspective, one might want to compare the active interventions to shelter only, but for ethical reasons, we did not want to take any options away from vulnerable families. Usual care consisted of whatever combination of services families could find on their own or with whatever help they could secure. All families were recruited to the study from emergency shelters, so families in this group typically started with a longer stay in shelters that provide relatively intense case management services. Some families then found their way into a variety of programmes, including each of the three special interventions. The usual care condition shows how the homeless service system works in the absence of priority offers to specific intervention programmes. No family was made worse off by participating in the study and, collectively, families received access to additional housing and service options.

The experiment was not a demonstration programme, where researchers design and implement interventions with high fidelity to an ideal model; rather, the study examined nearly 150 existing programmes in 12 communities with different characteristics spread throughout the United States. More detail about the communities and the programmes representing each of the interventions may be found in Gubits et al. (2013).

Methods

Participants

The study enrolled 2,282 families who consented to participate after they had stayed in emergency homeless shelters for at least a week. The typical family was a woman with a median age of 29, along with one or two children. Over a quarter (27.4 percent) had a spouse or partner with them in the shelter, and an additional one tenth (10.1 percent) had a partner who was not in the shelter. Qualitative data (Mayberry et al., 2014) suggest that shelters in the United States still exclude men, and families with configurations other than one or two parents with children under 18. Although most families who become homeless in the United States are homeless only once and fairly briefly (Culhane et al., 2007), a cross-sectional sample such as ours includes more families with longer or repeated stays in shelters. In addition, the fact that we enrolled families only after they had spent at least seven days in shelter probably led to a relatively needy group (we did not want to offer expensive programmes to families who could resolve their homelessness quickly without special intervention). Families had a median annual household income of $7,400 – far too low to afford housing in the private rental market. Three-fifths (63 percent) had been homeless previously, and 30 percent had symptoms of psychological distress or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). One in seven families (14 percent) reported drug abuse and an overlapping one in nine (11 percent) reported alcohol dependence. Almost half (48.9 percent) had experienced domestic violence as an adult.

Research design

The Family Options study was designed as an experiment. We would have liked simply to assign families to the different interventions randomly, but many programmes for people experiencing homelessness have eligibility requirements and we did not want to send families to programmes that we knew would turn them down. Nor did we want to ask programmes to distort their service models by taking families that they did not feel equipped to serve. Thus, we asked families questions to determine whether they met the eligibility criteria specified by programmes for each programme that had an opening at the time the family enrolled in the study. Then we randomized families among the interventions for which there was at least one programme with a current opening for which they appeared eligible. All families were eligible for usual care by definition. To preserve the integrity of the experiment, in comparing families offered an intervention with families in usual care, we included only those usual care families who were eligible for the intervention but did not receive any special offer. That means that we compared a slightly different group of usual care families with each of the interventions. Similarly, in comparing interventions with one another, we included only families eligible for both. In essence, we have six mini-experiments comparing pairs of interventions for well-matched groups of families. This article summarizes the three comparisons of active interventions with usual care. Additional detail and comparisons of interventions with one another can be found in Gubits et al. (2015).

Families assigned to an intervention did not have to take it up. Rather, they received a priority offer to a specific programme that had a vacancy reserved for them. Families assigned to each intervention could and did find their way into a variety of programmes. Nevertheless, families were more likely to use the intervention where they got a priority offer. For example, 84 percent of families assigned to permanent subsidies took up offers of subsidized housing compared to 12 percent of comparable usual care families (25 percent of usual care families if we include all forms of permanent subsidy). For rapid re-housing, 60 percent of families assigned to the intervention took up rapid re-housing compared to 20 percent of comparable usual care families; for project-based transitional housing, it was 54 percent vs. 29 percent. Families also used their assigned interventions for longer periods (Gubits et al., 2015).

At the 20 month follow-up point, we re-interviewed respondents in 1,857 families – 81.4 percent of the original sample. We also randomly selected up to two children from each family, we directly assessed 876 children between 3½ and 7 years of age and we interviewed 945 older children. Because families who took up offers likely differed from those who did not take them up, we examined all families who received priority offers of each intervention with the well-matched group of families in usual care who were eligible for the offer but did not receive it. (This analysis strategy is known as Intent-to-Treat.)

Measures

We focus here on 18 outcomes – three or four in each of the domains of housing stability, adult well-being, family preservation, child well-being and self-sufficiency (as listed in Table 1). We pre-selected these 18 outcomes (prior to seeing results) for presentation in the Executive Summary of the project report. Pre-selection guards against over-interpreting scattered effects among a much larger number of measures. The full report (Gubits et al., 2015) includes a full description of the measures, and also outcomes for a larger set of 73 measures.

Table 1.

Intervention Impacts at 20 Months Following Random Assignment (RA)

| Outcome | Mean Usual Care | Permanent Subsidy vs. Usual Care | Rapid Re-housing vs. Usual Care | Transitional Housing vs. Usual Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing Stability | ||||

| A. At least one night homeless or doubled up in past 6 months (percent) | 40,2 | −24,9*** | −3,0 | −4,6 |

| B. Any stay in emergency shelter months 7 to 18 (percent) | 27,8 | −12,9*** | −2,1 | −8,2** |

| Either A or B above (percent) (confirmatory)a | 50,1 | −28,0*** | −3,5 | −7,7* |

| Number of places lived past 6 months | 1,76 | −0,37*** | −0,09 | −0,09 |

| Adult Well-Being | ||||

| Fair or poor health (percent) | 31,5 | 0,1 | −3,8 | 1,9 |

| Psychological distress (z) | 0,00 | −0,15*** | −0,07 | 0,01 |

| Alcohol dependence or drug abuse (percent) | 14,5 | −4,5* | −3,1 | −0,5 |

| Intimate partner violence in past 6 months (percent) | 11,6 | −6,7*** | −1,1 | −1,1 |

| Family Preservation | ||||

| At least one child separated in past 6 months (percent) | 15,4 | −7,1*** | −2,0 | −0,6 |

| Spouse/partner separated in past 6 months (percent) (base: those with partner present at RA) | 36,5 | 0,7 | 9,4 | 1,2 |

| Child reunified (percent) (base: those with child separated at RA) | 27,1 | 5,0 | 6,1 | 1,9 |

| Child Well-Being | ||||

| Number of schools since RA | 1,96 | −0,21*** | −0,05 | −0,07 |

| Child care/school absences in past month | 0,95 | −0,15* | −0,13* | 0,06 |

| Fair or poor health (percent) | 4,6 | 0,5 | −0,1 | 2,5 |

| Behaviour problems (z) | 0,58 | −0,12 | −0,13 | −0,13 |

| Self Sufficiency | ||||

| Work for pay week before survey (percent) | 31,3 | −5,7** | −0,1 | 3,1 |

| Total family income ($) | 9067 | −460 | 1128** | 818 |

| Household is food secure (percent) | 64,5 | 9,9*** | 6,1* | 2,7 |

| Number of families | 578 | 944 | 906 | 556 |

Source: Family Options Study (Gubits et al., 2015)

p <.10,

p <.05,

p <.01

After adjustment for multiple comparisons, the confirmatory outcome remains significant at p <.01 for permanent subsidy vs. usual care, but it is not significant for transitional housing vs. usual care.

Most measures were self-reports, with the exception of any stay in emergency shelter in months 7 to 18, which were obtained largely from records of the local Homelessness Management Information System, which records contacts with the homeless service system. Other outcomes in the housing stability domain were self-reports of homelessness (defined as living in a homeless shelter, temporarily in an institution, or in a place not typically used for sleeping) or doubling up (defined as living with a friend or relative because you could not find or afford a place of your own), and the number of places lived in the last six months.

Adult well-being included two single-item reports of fair or poor health (on a five-point scale) and experience of being physically abused or threatened with violence by a romantic partner. Psychological distress was measured with the Kessler-6 index of symptoms (Kessler et al., 2003) transformed to z-scores; alcohol dependence with the Rapid Alcohol Problems Screen (RAPS4: Cherpitel, 2000); and drug abuse with the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10: Skinner, 1982).

To assess family preservation we conducted family rosters, with information about each family member with the respondent in the shelter at the outset of the study (the baseline interview), and then information about the whereabouts of those family members 20 months later. Separations and reunifications involved changes from the family in the shelter at the baseline.

Child well-being included parent reports of three one-item measures of the number of schools the child had attended since the baseline interview, the number of absences from school in the past month (the last month that school was in session if over the summer), and physical health, as for adults. The last measure was the average of four parent reports on questions in four domains of problem behaviour on the ‘Strengths and Difficulties’ questionnaire, standardized for age and gender to a national sample (Goodman, 1997).

Self-sufficiency included whether the respondent had worked for pay in the week before the survey, and two multi-item measures. The first series of questions attempted to estimate income from all sources in the most recently completed calendar year. The second assessed food insecurity using standard questions from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (Nord et al., 2005).

We also assessed the costs of the interventions in two ways: the average monthly cost of actually using a typical programme that provided each intervention, and the total cost of all the housing programmes used by families assigned to each intervention group. The latter depended both on the mix of programmes that families used and the length of time they used them for.

Results

The Service System

The first lessons from the study were about the service system. We initially screened 2,490 families, but excluded 1833 because they were not eligible for available slots in at least two of the interventions (later, at least one) in their community in addition to usual care. Some families lost interventions because they were temporarily or permanently unavailable in their communities at the time they applied. Further, many families lost interventions because they did not pass eligibility screenings. Over a quarter of families were deemed ineligible for any transitional housing programme in their community on the basis of the screening prior to random assignment, and only a little over half of those who received a priority offer of transitional housing moved in. (We cannot tell to what extent families rejected programmes and to what extent programmes conducted additional screening and turned down families.) Rapid re-housing programmes excluded far fewer families up front – under 10 percent – but only three-fifths of those with priority offers found and leased a unit. Thus, the mainstay programmes in the homeless service system either excluded or were unattractive to many homeless families. By contrast, the housing subsidy programmes, which typically have long waiting lists so that they are not ordinarily available to families at the time they become homeless, screened out less than 5 percent of families, and 84 percent of families who got a priority offer found a landlord who would accept a voucher and moved in (a far higher proportion than in many studies of voucher take-up).

Intervention Impacts

The central lessons of the study concern the impact of receiving a priority offer of one of the interventions compared to not receiving any special offer. Table 1 shows results comparing families in each intervention group with comparable usual care families for the 18 outcomes that were pre-selected for presentation in the Executive Summary of the project report. We also chose one outcome (the ‘confirmatory outcome’) and adjusted statistical significance levels for multiple comparisons for this outcome only. All other results are deemed exploratory, although the consistency of the patterns suggests more than chance findings. We pre-specified both the methods of analysis and a significance level of.10. The full report (Gubits et al., 2015) describes the statistical analysis in detail, including weighting for non-response and control variables.

Column 1 of Table 1 shows the percentage of families who experienced an outcome for dichotomous measures (or the mean for continuous variables such as number of moves and psychological distress) for the entire usual care sample. This allows us to understand how families who got no special offer of assistance fared 20 months after a stay in emergency homeless shelters. The remaining columns in Table 1 show comparisons of the three interventions to usual care, where only the usual care families eligible for the named intervention are included in each comparison. So, for example, the first row shows that 40.2 percent of families who received no special offer of assistance reported being homeless or doubled up with another household in the six months prior to the follow-up survey. Assignment to a priority offer of a housing subsidy reduced that number by 24.9 percentage points – over half – a result that was highly statistically significant. Assignment to priority offers of the other interventions had small and non-significant effects.

Housing stability

Families who got no special offer of intervention remained residentially unstable 20 months after entering shelter. Half of the usual care families had either stayed in emergency shelters recently or been doubled up. (This outcome encompasses the ETHOS Typology of Homelessness and Social Exclusion categories 1, 2, 3.1 and 4 for homelessness, and 8.1 for doubling up: FEANTSA, undated). Priority offers of permanent housing subsidies reduced self-reported homelessness and doubling up in the past six months by more than half and shelter stays in the past year by almost half. All families had to have stayed in at least one place in the past six months; assignment to permanent subsidies reduced additional places by almost half. Project-based transitional housing had more modest effects on homelessness, but not on doubling up or residential mobility. Rapid re-housing was equivalent to usual care in this domain. Although not a pre-selected outcome, initial shelter stays were shortened by about the same amount – half a month – by priority access to each of the three interventions.

Adult well-being

One in seven adults in usual care reported alcohol or drug dependency, and one in eight reported intimate partner violence in the past six months. Levels of psychological distress were high (here reported as standard scores so that the mean in the usual care group is 0). Priority offers of permanent subsidies reduced dependence on alcohol or drugs by almost a third and intimate partner violence by almost half. It also reduced psychological distress but did not affect physical health. Assignment to rapid re-housing and transitional housing had no impacts on these measures.

Family preservation

Fifteen percent of usual care families had a child separated from the family in the past six months and (although not a pre-selected outcome) 4 percent had a child placed in foster care. Priority access to housing subsidies reduced child separations by two fifths and foster care placements by three fifths. Assignment to rapid re-housing and transitional housing had no impact on either outcome. None of the interventions affected separations from spouses or partners, or reunifications (albeit for a much smaller sample of families who had a child living elsewhere at the time of the initial interview in shelter).

Child well-being

Child well-being outcomes were assessed only for children who remained with their families. Because subsidies reduced separations, there was a broader group of children for the subsidy intervention than for usual care. Children in families offered subsidies moved among schools less often – about one fewer move for every five children. Offers of both permanent subsidies and temporary rapid re-housing subsidies reduced school absences by equivalent amounts. Priority offers of transitional housing had no impact on these outcomes. None of the interventions affected child health or behaviour. There were relatively few effects on the broader set of outcomes in this domain that were not pre-selected for inclusion in the executive summary.

Self-sufficiency

Fewer than a third of respondents in usual care worked for pay in the week before the follow-up survey. Family incomes averaged $9,067 per year – higher than at study entry but still too low to rent unsubsidized units in the private rental market. Priority offers of permanent subsidies reduced the number of families who worked for pay by a fifth; this and other work-related outcomes not included in the Executive Summary were the only adverse impacts of the subsidy intervention. Interestingly, incomes were not affected. Assignment to both permanent subsidies and to temporary rapid re-housing subsidies increased the proportion of families who reported having secure access to food from two thirds to three quarters of families. Priority offers of rapid re-housing resulted in a $1,128 increase in family income – still too low for private rentals. Priority offers of transitional housing had no impact on self-sufficiency.

Lack of differential effects based on family needs

An important question is whether all families need permanent housing subsidies or whether some families could do as well with a shorter intervention. Similarly, although transitional housing was not very effective in this study, might the services it provides be important for allowing some families to succeed? We attempted to understand whether the interventions were differentially effective for families with lower and higher needs, defined in two ways. The first was the number of psychosocial challenges, such as interpersonal violence, substance abuse or mental health problems that families reported at the outset of the study before random assignment. The second was the number of housing barriers, such as lack of money to pay rent, lack of employment or poor credit history that families reported at the same time. To examine whether interventions worked better for families with greater or lesser levels of needs, we tested the statistical interactions of each index (separately) with each of the interventions used in the prediction of the outcomes listed in Table 1. The number and pattern of findings did not exceed what would be expected by chance alone.

Costs

The costs per month of actually using a service were lowest for rapid re-housing ($878), intermediate for subsidized housing ($1,162) and highest for transitional housing ($2,706) and emergency shelters ($4,819), with considerable variation across sites and programmes. Families in all intervention arms used a variety of programmes, and so the cost for families given priority offers of different interventions varied by only about 10 percent over the course of the follow-up period. The cost estimates showed clearly that usual care cost far more than no treatment: the total cost of the housing and service programmes used by the usual care group was about $30,000 over 20 months. Surprisingly, the permanent subsidies cost about the same over 20 months as usual care. This was because families in usual care used more shelter and transitional housing, which are both expensive. Rapid re-housing cost less than usual care over 20 months, and transitional housing cost more.

Discussion

Priority offers of housing subsidies, when compared to usual care, had salutary effects in each of the five outcome domains over the 20-month follow-up period, with positive impacts on 10 of the 18 pre-selected outcomes, and a negative impact on one. Subsidies, without any psychosocial services, not only had strong effects on housing outcomes but also had radiating impacts in other domains, consistent with the theory that homelessness for families in the United States is a housing affordability problem that subsidies can solve, and that secure housing provides a platform for families to deal with other problems on their own. Subsidies remove a major stressor in families’ lives and allow them to focus on other issues.

Priority offers of transitional housing had more modest effects on homelessness (but not on doubling up) relative to usual care, perhaps because transitional housing can last up to 24 months and a number of families were still in transitional housing programmes at the time of the follow-up survey. This intervention did not have effects on other outcomes. In particular, the psychosocial services in transitional housing did not affect well-being or self-sufficiency. The study provides little support for the housing readiness approach of transitional housing, where services leading to changes in these outcomes are theorized to lay the foundation for later success in housing.

Priority access to rapid re-housing increased incomes and food security and reduced children’s absenteeism from school, but had no effect on housing outcomes, family separation or adult well-being relative to usual care. Although three quarters of families in usual care avoided shelter in the months leading up to the follow-up interview, the temporary subsidies provided by rapid re-housing programmes were simply not enough to help families do better. The primary selling points for rapid re-housing are its lower costs and its positive effects on family income. If incomes continue to grow, they may enable more families to rent housing in the private market in the future. If the homeless service system is unable to gain access to additional permanent subsidies, then using resources for rapid re-housing, which attains slightly better results than usual care at lower cost, would be advantageous.

None of the interventions had any impact for families with greater or lesser levels of need defined in terms of psychosocial challenges or housing barriers. The study’s best guidance for policy and practice is reflected in the average findings across all families.

The idea that permanent housing subsidies would reduce homelessness is not a radical one. Nor is the idea that subsidies reduce work effort, whether because the subsidies reduce the need for work, or because reducing housing costs to 30 percent of income effectively imposed a 30 percent marginal tax on income (in addition to other taxes a family pays). Another large experimental study of offering housing vouchers to families receiving public assistance (welfare benefits) also found a short-term diminution of work effort that dissipated after five years (Mills et al., 2006).

Other findings of the study are more novel. The radiating benefits of permanent subsidies for family preservation, adult and child well-being, and food security have not been shown previously. The fact that offering families subsidies costs about the same as not giving them any special offer over a 20-month period is also surprising. The study is continuing to follow families for three years, and we will determine whether these impacts hold up over the longer period, and whether costs diverge if families continue to use permanent subsidies while families without specific offers use fewer.

Our results are at odds with observational studies of rapid re-housing in the United States. Differences could be due to the selection of families in the observational studies (the enrolment phase showed that only a little more than half of families screened for rapid re-housing passed the screening and also took up the intervention). Families in our study had all spent at least a week in a shelter and three-fifths had been homeless previously; rapid re-housing subsidies often go to families in their first episode of homelessness, sometimes even before a shelter stay; temporary subsidies may be sufficient for individuals or families with lower levels of need. Lack of take-up could have diluted programme effects, or programmes in different sites could be differentially successful due to either programme characteristics or site characteristics; our draw of a dozen sites had little overlap with sites studied previously.

Generalizations from different countries with different social systems should always be approached with caution. In the United States, our results suggest the importance of housing subsidies in reducing family homelessness, but the international lesson may be more about the relative importance of focusing on housing affordability in comparison to psychosocial issues in addressing family homelessness. The United States is clearly an outlier among wealthy countries in relative poverty because of its anaemic tax and transfer programmes; child poverty in the United States is particularly high (Gornick and Jäntti, 2016), but conversations with service providers in Dublin and Melbourne suggest that homelessness among families is on the rise in both of those cities, as housing costs outstrip incomes at the bottom of the distribution chain. Paradoxically, improvements in the labour market may make this situation worse, as middle class workers bid up rents beyond what poor people can afford (O’Flaherty, 1996). Homeless advocates may want to consider the role that housing affordability plays in countries where family homelessness is on the rise, and what policy levers can be used to raise incomes or lower costs to make housing more affordable for the poorest families.

Footnotes

Funding for this paper was provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Contract DU206SF-13-T-00005 to Abt Associates, Inc., and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant R01HD666082 to Vanderbilt University.

Ranks for family homelessness are from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2015) point-in-time counts, Exhibit 3.1. Housing costs and local minimum wages are from the National Low Income Housing Coalition (2015) figures for each jurisdiction.

A few additional families without children aged 15 or under were later excluded from analysis.

Contributor Information

Marybeth Shinn, Vanderbilt University.

Scott R. Brown, Vanderbilt University

Michelle Wood, Abt Associates.

Daniel Gubits, Abt Associates.

References

- Burt MR. Life After Transitional Housing for Homeless Families. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne T, Treglia D, Culhane DP, Kuhn J, Kane V. Predictors of Homelessness among Families and Single Adults after Exit from Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-housing Programs: Evidence from the Department of Veterans Affairs Supportive Services for Veteran Families Program. Housing Policy Debate. 2016;26(1):252–275. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ. A Brief Screening Instrument for Problem Drinking in the Emergency Room: The RAPS-4. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(3):447–449. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane DP. The Quandaries of Shelter Reform: An Appraisal of Efforts to ‘Manage’ Homelessness. Social Service Review. 1992;66(3):428–440. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane DP, Metraux S, Park JM, Schretzman M, Valente J. Testing a Typology of Family Homelessness Based on Patterns of Public Shelter Utilization in Four U.S. Jurisdictions: Implications for Policy and Program Planning. Housing Policy Debate. 2007;18(1):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Gillespie S, Anderson J. Rapid Re-housing: What the Research Says. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- FEANTSA (undated) ETHOS Typology of Homelessness and Social Exclusion. [on-line] Available from: www.feantsa.org/spip.php? article 120 [17.05.2016].

- Goodman RN. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornick JC, Jäntti M. Child Poverty in Cross-National Perspective: Lessons From The Luxembourg Income Study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(3):558–568. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick JC, Jäntti M. Pathways: The Poverty and Inequality Report, 2016. Stanford: Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality; 2016. Poverty; pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gubits D, Spellman B, Dunton L, Brown S, Wood M. Interim Report: Family Options Study. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gubits D, Shinn B, Bell S, Wood M, Dastrup S, Solari CD, Brown S [Scott], Brown S [Steven], Dunton L, Lin W, McInnis D, Rodriguez J, Savidge G, Spellman BE. Family Options Study: Short-term Impacts of Housing and Services Interventions for Homeless Families. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jusko K. Pathways: The Poverty and Inequality Report, 2016. Stanford: Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality; 2016. Safety Net; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand ST, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, Shinn M, Benton JG, Wise J. Families Experiencing Housing Instability: The Effects of Housing Programs on Family Routines and Rituals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84(1):95–109. doi: 10.1037/h0098946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills G, Gubits D, Orr L, Long D, Feins J, Kaul B, Wood M, Jones A, Cloudburst Consulting and the QED Group . Effects of Housing Vouchers on Welfare Families: Final Report. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Low Income Housing Coalition. Out of Reach 2015. 2015 [on-line] Available at: http://nlihc.org/oor[17.05.2016.

- Nord M, Andrews M, Carlsen S. Household Food Security in the United States, 2004. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Northwest Institute for Children and Families, University of Washington, School of Social Work. Final Findings Summary: A Closer Look at Families’ Lives During and After Supportive Transitional Housing. Seattle: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; 2007. Evaluation of the Sound Families Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- O’Flaherty B. Making Room: The Economics of Homelessness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M. Homelessness: What is a Psychologist to do? American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20(1):1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00942179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Weitzman BC, Stojanovic D, Knickman JR, Jimenez L, Duchon L, James S, Krantz DH. Predictors of Homelessness among Families in New York City: From Shelter Request to Housing Stability. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(11):1651–1657. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behavior. 1982;7(4):363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeeding T. Public Policy, Economic Inequality and Poverty: The United States in Comparative Perspective. Social Science Quarterly. 2005;86(supp):955–983. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wong YLI, Culhane DP, Kuhn R. Predictors of Exit and Reentry Among Family Shelter Users in New York City. Social Service Review. 1997;71(3):441–462. [Google Scholar]

- Wood M, Turnham J, Mills G. Housing Affordability and Family Well Being: Results from the Housing Voucher Evaluation. Housing Policy Debate. 2008;19(2):367–412. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Robertson MJ, Lahiff M. Getting off the Streets: Economic Resources and Residential Exits from Homelessness. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27(2):209–224. [Google Scholar]