Abstract

Rationale:

Posteromedial dislocations of the elbow with lateral humeral condylar fractures (LCFs) are uncommon, and only isolated cases have been reported in the English-language literature. Because of the complex radiolucent cartilaginous structures and late-appearing ossification centers, radiological diagnosis of elbow dislocations with LCF in children is challenging.

Patient Concerns:

We report three children with posteromedial elbow dislocation: two patients with Milch type I and one patient with Milch type II LCF.

Diagnoses:

In our report, radiographs showed only a small bone fragment, and arthrography or computed tomography were helpful diagnostic aids in cases 1 and 3. In contrast, the patient in case 2 was initially misdiagnosed as having an epiphyseal separation of the distal humerus, and open reduction and internal fixation through the posterior approach revealed Milch type II LCF.

Interventions:

In case 1 and 3, Milch type I LCFs, open reduction and internal fixation was performed through the posterolateral approach. On the other hand, in case 2, Milch type II LCF, open reduction and internal fixation was performed through the posterior approach.

Outcomes:

Poor reduction of Milch type I LCFs resulted in incongruity of the articular surface and poor cosmetic results in two patients. In case 2, Milch type II LCF, plain radiographs showed adequate healing without elbow deformity and the clinical result was excellent.

Lessons:

Because LCFs are intra-articular fractures, anatomical reduction is crucial for satisfactory outcomes. We promote awareness of this injury, especially posteromedial dislocation with Milch type I LCF. Preoperative evaluation is helpful for achieving satisfactory outcomes, and open reduction and internal fixation through an anterolateral approach might be most appropriate for Milch type I LCFs.

Keywords: children, elbow dislocation, fracture and dislocations, lateral humeral condylar fracture, posteromedial elbow dislocation

1. Introduction

Lateral humeral condylar fractures (LCFs) are the second most common injury after supracondylar fractures and represent approximately 12% of all elbow fractures in children.[1] In contrast, elbow dislocations with LCFs are much less common in children, and there are only isolated case reports in the English-language literature.[2–12] Typical radiographs of elbow dislocations with LCF show that the elbow joint is dislocated posteromedially while the displaced lateral condyle is aligned with the radial head.[2–4,6,7,10,12]

From April 2000 to March 2015, we found only 3 cases (3.4%) of posteromedial elbow dislocation with LCF among 88 patients with LCF treated in our institution and 2 related hospitals. In this report, we review these posteromedial elbow dislocations with LCF and compare our results with the published literature to identify treatment strategies based on the fracture type using Milch classification.[13]

2. Case presentation

2.1. Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from each patient's parents for operation and for publication of the details their respective cases.

2.2. Case 1

A 1-year-old boy was involved in a traffic accident and fell on his right arm (Fig. 1A, B). Under general anesthesia, closed reduction for the elbow dislocation was performed, but the joint revealed remarkable instability to varus stress. Preoperative arthrography showed Milch type I LCF. Open reduction and internal fixation was then performed through a posterolateral approach.[14] Briefly, an incision was made posterolaterally starting at the distal third of the humerus and extending to the olecranon, deviating radially. After dissecting through the subcutaneous tissue, the fascial layer on the triceps was separated at its lateral border. The intermuscular plane between the triceps and brachioradialis was then separated to access to the distal humerus, retracting the lateral border of the triceps medially. Inspection of the posterior aspect of the lateral condyle revealed the fracture line on the capitellum, suggesting Milch type I LCF. The fracture fragment was reduced and fixed with two 1.5-mm smooth Kirschner wires (K-wires). Postoperative radiographs showed inadequate reduction of the LCF and increased Baumann angle of 86° compared with the contralateral side at 67° (Fig. 2A, B). After immobilization in a long arm cast for 6 weeks, active and active-assisted range of motion (ROM) exercise was encouraged, and the K-wires were removed after 3 months, under general anesthesia. At the final follow-up 16 months postoperatively, elbow ROM was 0° in extension and 140° in flexion, which was the same as the contralateral side. However, Baumann angle was increased and the carrying angle was decreased compared with the contralateral side. The anteroposterior radiographic view showed cubitus varus deformity and −7° for the carrying angle (Fig. 3A, B). Based on Flynn et al's criteria (Table 1),[15] functional outcome was excellent, but cosmetic outcome was poor, suggesting that the clinical result was also poor (Table 2).

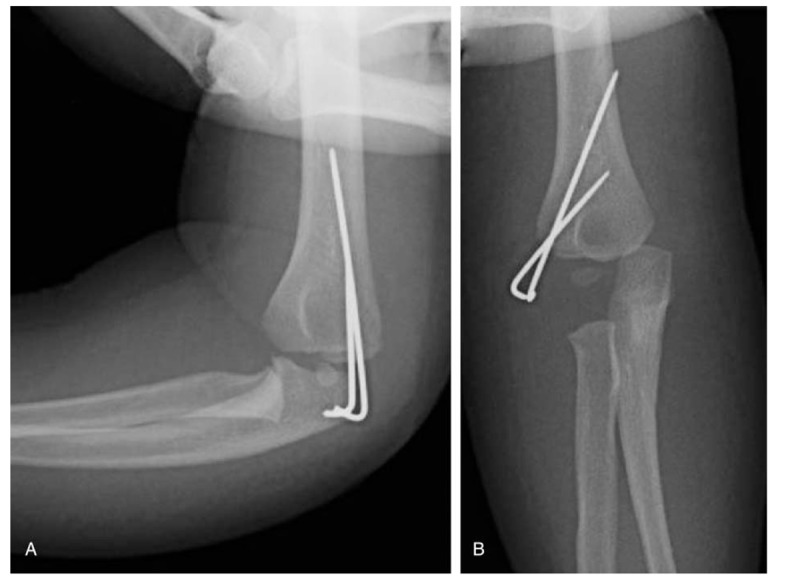

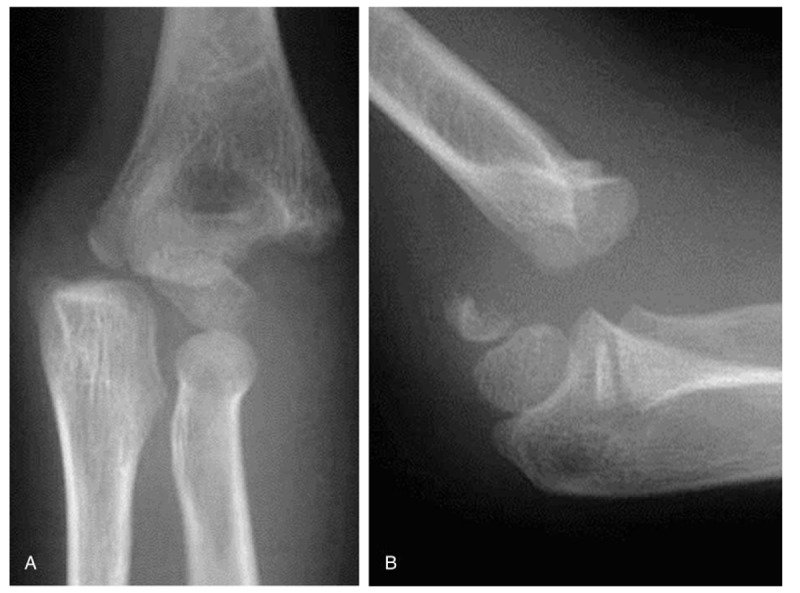

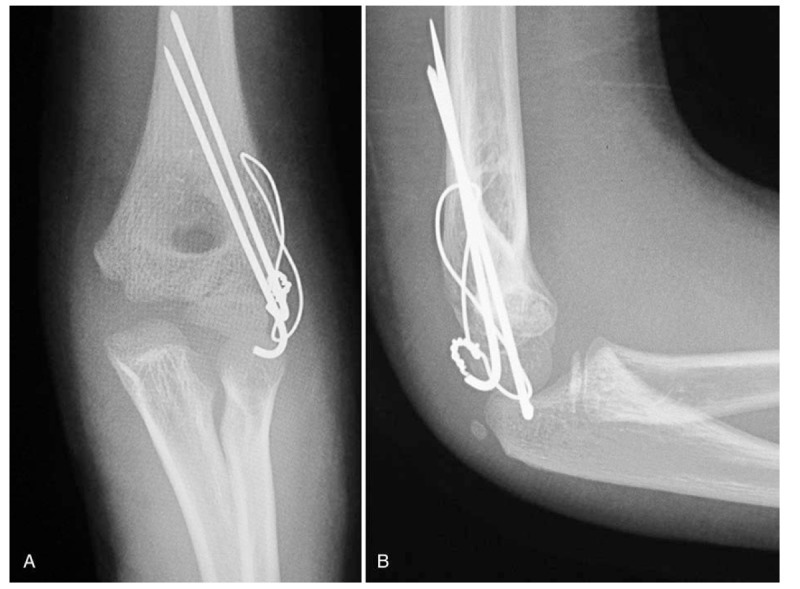

Figure 1.

Preoperative radiographs (A, B) of the right elbow in case 1 showing posteromedial dislocation of the elbow joint.

Figure 2.

Postoperative radiographs (A, B) of the right elbow in case 1 showing inadequate reduction of the lateral condylar fracture and increased Baumann angle of 86° compared with the contralateral side at 67°.

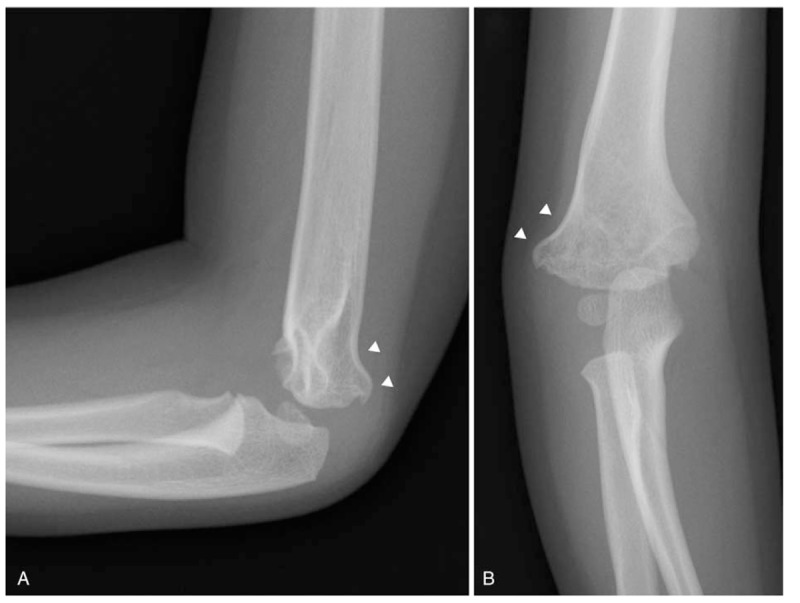

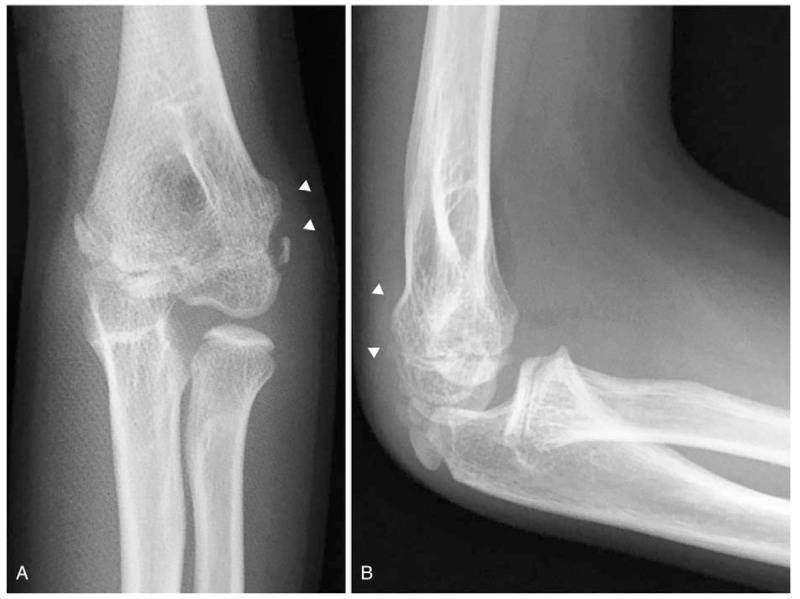

Figure 3.

Radiographs (A, B) of the right elbow in case 1, 16 months postoperatively showing marked cubitus varus deformity of the elbow. White arrowheads indicate the deformity of the distal humerus.

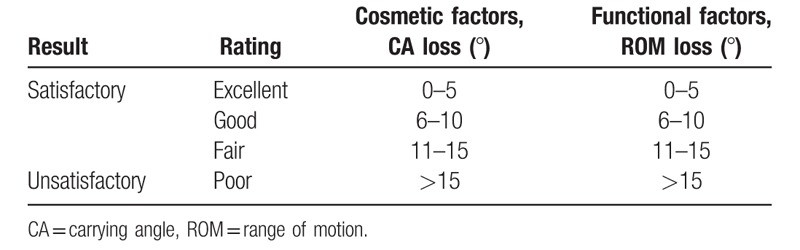

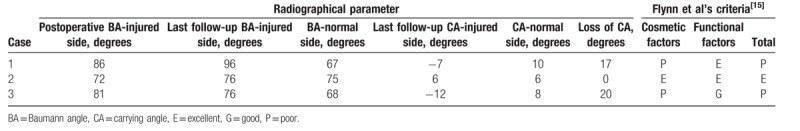

Table 1.

Flynn et al's criteria.[15].

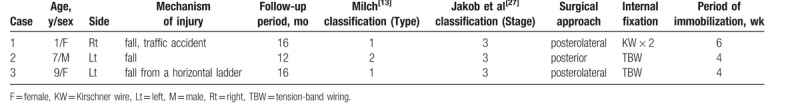

Table 2.

Demographic data for pediatric patients with posteromedial dislocations and lateral humeral condylar fractures.

2.3. Case 2

A 7-year-old boy fell onto his left outstretched hand while running (Fig. 4A, B). He was initially diagnosed as having an epiphyseal separation of the distal humerus and underwent closed reduction and percutaneous pinning. However, the fracture fragments were not adequately reduced, and 2 days after injury, open reduction and internal fixation were performed through a posterior approach. Direct inspection of the distal humerus revealed a fracture line on the trochlear groove, a Milch type II LCF. After anatomical reduction, internal fixation for the LCF was performed using two 1.5-mm K-wires and tension-band wiring. Postoperative radiographs showed anatomical reduction and almost identical Baumann angles on the affected and contralateral sides (Fig. 5A, B). Active ROM exercise was encouraged following immobilization in a long arm cast for 4 weeks, and K-wires were removed after 3 months, under general anesthesia. At the final follow-up 12 months postoperatively, elbow ROM was 0° in extension and 145° in flexion, which was the same as the contralateral side. Plain radiographs showed adequate healing without elbow deformity (Fig. 6A, B). Based on Flynn et al's criteria, the clinical result was excellent (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Preoperative radiographs (A, B) of the left elbow in case 2 showing posteromedial dislocation of the elbow joint.

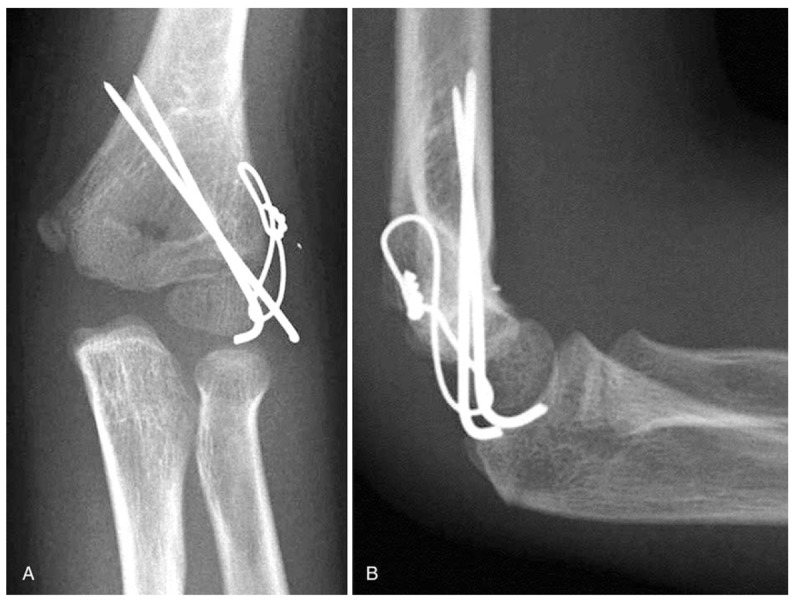

Figure 5.

Postoperative radiographs (A, B) of the left elbow in case 2 showing adequate reduction of the lateral condylar fracture and a similar Baumann angle of 72° compared with the contralateral side at 75°.

Figure 6.

Postoperative radiographs (A, B) of the left elbow in case 2 at 12 months showing adequate healing without elbow deformity.

2.4. Case 3

A 9-year-old girl fell from an overhead horizontal ladder onto her left outstretched hand injuring her elbow (Fig. 7A, B). Computed tomography showed a vertical fracture line into the distal lateral humeral condyle, a Milch type I fracture (Fig. 8A–C). Under general anesthesia, open reduction and internal fixation through a posterolateral approach was performed. After anatomical reduction, internal fixation for the LCF was performed using two 1.5-mm K-wires and tension-band wiring. Postoperative radiographs showed increased Baumann angle of 81° compared with the contralateral side at 68° (Fig. 9A, B). Active ROM exercise was encouraged after immobilization in a long arm cast for 4 weeks, and K-wires were removed after 6 months, under general anesthesia. At the final follow-up 16 months postoperatively, elbow ROM was 0° in extension and 145° in flexion, which was the same as the contralateral side. However, Baumann angle was increased and the carrying angle was decreased compared with the contralateral side. The anteroposterior radiographic view showed cubitus varus deformity and −12° for the carrying angle (Fig. 10A, B). Thus, functional outcome was excellent, but cosmetic outcome was poor, suggesting that the clinical result was also poor (Table 1).

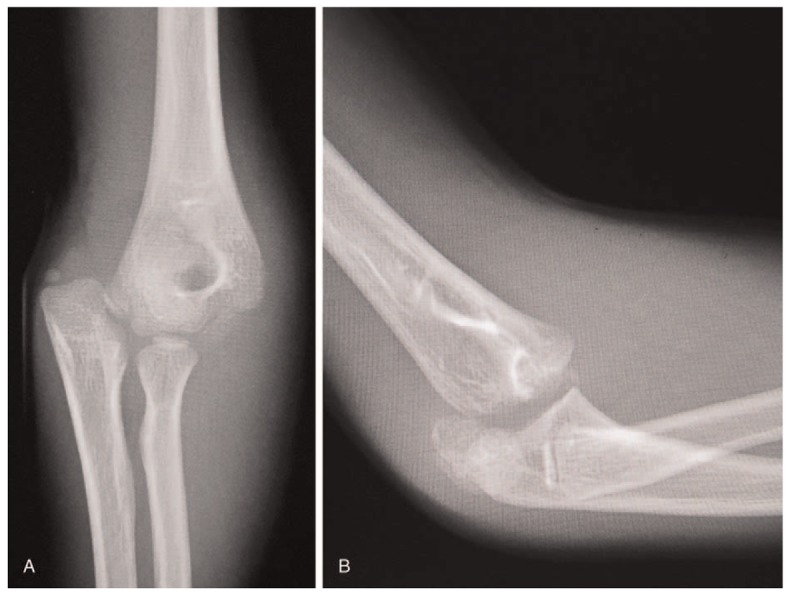

Figure 7.

Preoperative radiographs (A, B) of the left elbow in case 3 showing posteromedial dislocation of the elbow joint.

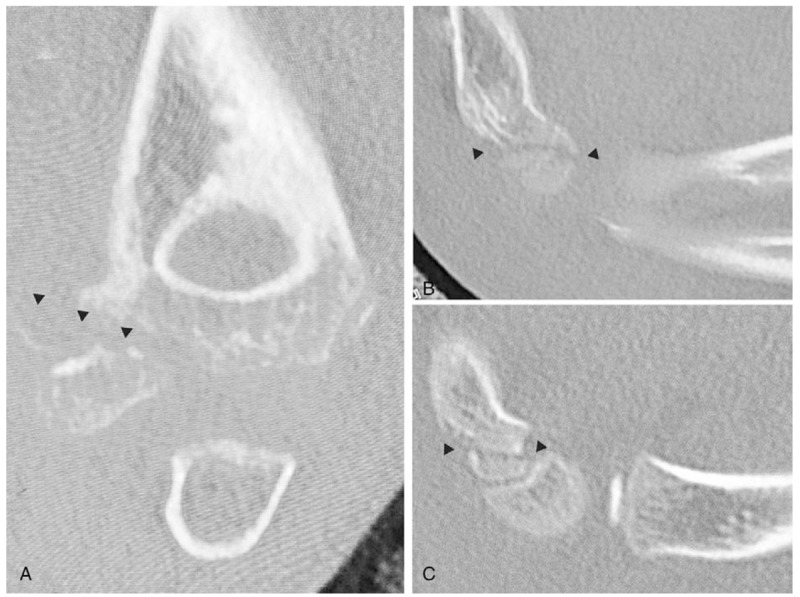

Figure 8.

Computed tomographic images. Coronal image (A) and Sagittal images (B, C) of the left elbow in case 3 showing Milch type I lateral humeral condylar fracture. Black arrowheads indicate the fracture lines of the distal humerus.

Figure 9.

Postoperative radiographs (A, B) of the left elbow in case 3 showing inadequate reduction of the lateral condylar fracture and an increased Baumann angle of 81° compared with the contralateral side at 68°.

Figure 10.

Radiographs (A, B) of the left elbow in case 3, 16 months postoperatively showing decreased carrying angle in the elbow, and the anteroposterior view showing cubitus varus deformity. White arrowheads indicate the deformity of the distal humerus.

3. Discussion

Dislocations of the elbow joint, which usually involve medial epicondylar fractures, are a common injury in children, and dislocations are usually in the posterior or posterolateral direction.[12,16] In contrast, elbow dislocations involving LCF are uncommon in children and only isolated cases have been reported (Table 3)[2–12] including 2 cases in 47 patients with LCF (4.3%)[17] in 1 report and 1 case in 23 patients <15 years of age with elbow dislocation (4.3%) in another report.[16] These findings are consistent with our report of 3 cases in 88 patients with LCF (3.4%). Because of the complex radiolucent cartilaginous structures and late-appearing ossification centers, radiologic diagnosis of elbow dislocations with LCF in children is challenging. Also, the typical radiographic appearance of this injury showing that dislocated LCFs are well-aligned with the radial head, is similar to epiphyseal separation of the humerus.[2–6,18–20] Therefore, epiphyseal separations are occasionally mistaken for elbow dislocations involving LCFs. In our report, radiographs showed only a small bone fragment, and arthrography or computed tomography were helpful diagnostic aids in cases 1 and 3. In contrast, the patient in case 2 was initially misdiagnosed as having an epiphyseal separation of the distal humerus, and open reduction and internal fixation through the posterior approach revealed the LCF. Thus, radiographs are not always useful for recognizing the fracture type because of the radiolucent cartilaginous structures, and other modalities, such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound, or arthrography, are recommended to aid in diagnosis.[21–26]

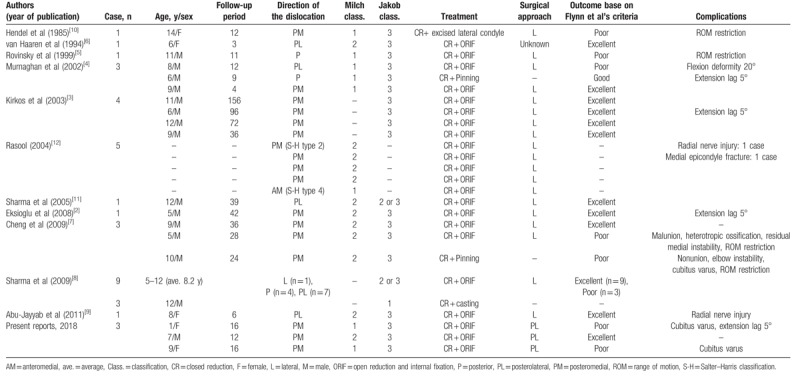

Table 3.

Radiographic evaluations and Flynn et al's criteria in the injured and contralateral limbs.

Generally, elbow dislocations are easily reduced using closed methods, with the indications for surgical treatment determined according to the displacement of the fracture fragment. Two classification systems are currently used to describe LCFs and to guide treatment: Jakob classification[27] and Milch classification.[13] Jakob et al classified LCFs into 3 stages based on the degree of displacement and rotation of the fracture fragment[27] as follows: stage I, fractures have <2 mm displacement, and the articular surface remains intact; stage II, fractures have >2 mm displacement with moderate displacement of the articular surface; and stage III, fractures have significant displacement and rotation. In contrast, Milch classification considers the anatomical position of the fracture line[13] as follows: type I, the fracture line courses lateral to the trochlea and passes through the capitulotrochlear sulcus; and type II, the fracture line extends into the apex of the trochlea. Based on previous reports of elbow dislocations involving LCFs, almost all cases were classified as Jakob stage III fractures. In contrast, Milch classification of the fracture types varied in previous reports (Table 2).

Because displaced pediatric LCFs are intra-articular fractures and epiphyseal fracture types 2 and 4 using the Salter–Harris classification, open reduction and internal fixation are generally recommended,[12,28,29] and the surgical approach should be chosen based on visualizing the fracture lines.[30,31] LCF lines are classified according to Milch classification.

Previous studies state that Milch type I LCFs are considered stable, because the lateral trochlear rim is preserved, and the intact capitellotrochlear groove acts as a lateral buttress for the ulnar coronoid-olecranon ridge. Generally, elbow dislocation with LCFs occur in Milch type II fractures.[5] However, several cases of elbow dislocations with Milch type I LCFs have been reported,[4,5,10,12] and 2/3 patients in our report suffered Milch type I LCFs.

Regarding clinical outcomes, several authors have reported poor results for elbow dislocations involving LCFs (Table 2). Some patients had complications, including restricted ROM,[4,7,10] non- or malunion of the LCF,[7] and cubitus varus deformity.[32] Satisfactory outcomes following open reduction and internal fixation for LCFs have been reported following anatomical reduction of the articular surface and when adequate bone union of the LCFs was obtained.[29,33] Poor outcomes result from inappropriate open reduction and internal fixation, which results in malunion of the articular surface or nonunion of the LCF. In our report, in cases 1 and 3, postoperative radiographs showed increased Baumann angle and decreased carrying angle compared with the contralateral side. In these cases, anatomical reduction of the articular surface of the capitellum was not obtained, based on postoperative radiographs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of published reports of pediatric patients with elbow dislocations and lateral humeral condylar fractures.

Although open reduction and internal fixation through a posterolateral approach[14,34] or lateral approach (Kocher approach)[3,4,7–10,12] is the standard treatment for displaced LCFs,[13] these approaches are not appropriate for visualizing the fracture line on the capitellum (Milch type I LCFs).[30,31] Because the articular surface of the capitellum is present only on the anterior side, only an anterolateral approach permits restoration of joint congruity. Thus, open reduction and internal fixation through an anterolateral approach is appropriate for Milch type I LCFs, but not posterolateral, lateral, and posterior approaches.[30] In contrast, because the articular surface of the trochlea is present both anteriorly and posteriorly, joint congruency can be restored in Milch type II LCFs through all approaches, including antero- or posterolateral, and lateral and posterior approaches. Failed anatomical reduction of the articular surface results in poor outcomes secondary to malunion and joint incongruity. In our report, open reduction and internal fixation through the posterior approach permitted anatomical reduction of a Milch type II LCF in case 2. However, open reduction and internal fixation through the posterolateral approach did not provide anatomical reduction for Milch type I LCFs in cases 1 and 3. Failed anatomical reduction of the articular surface of the capitellum might have led to cubitus varus in these cases. Therefore, when considering the ideal surgical approach for LCFs, preoperative imaging, including computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, is required. Also, the anterolateral approach is an optimal approach for Milch type I LCFs, although all approaches, including antero- or posterolateral, and lateral and posterior approaches, are appropriate for Milch type II LCFs.

The major limitation of the present study is that we only report the outcomes of 3 patients, but this reflects the rarity of this injury. Our case reports offer valuable insight into the treatment of posteromedial elbow dislocation with Milch types I and II LCFs.

4. Conclusion

We report 3 children with posteromedial elbow dislocation with 2 Milch type I and 1 Milch type II LCFs. Because LCFs are intra-articular fractures, anatomical reduction of the LCF is crucial for satisfactory outcomes. In our report, poor reduction of Milch type I LCFs resulted in incongruity of the articular surface and led to poor cosmetic results in 2 cases. Preoperative evaluation is helpful for achieving satisfactory outcomes, and open reduction and internal fixation through an anterolateral approach might be most appropriate for Milch type I LCFs.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jane Charbonneau, DVM, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Investigation: Yuji Tomori.

Project administration: Yuji Tomori.

Resources: Yuji Tomori.

Supervision: Mitsuhiko Nanno, Shinro Takai.

Writing – original draft: Yuji Tomori.

Writing – review & editing: Mitsuhiko Nanno.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: K-wires = Kirschner wires, LCF = lateral humeral condylar fracture, ROM = range of motion.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Landin LA, Danielsson LG. Elbow fractures in children. An epidemiological analysis of 589 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1986;57:309–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Eksioglu F, Uslu MM, Gudemez E, et al. Medial elbow dislocation associated with a fracture of the lateral humeral condyle in a child. Orthopedics 2008;31:93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kirkos JM, Beslikas TA, Papavasiliou VA. Posteromedial dislocation of the elbow with lateral condyle fracture in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;408:232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Murnaghan JM, Thompson NS, Taylor TC, et al. Fractured lateral epicondyle with associated elbow dislocation. Int J Clin Pract 2002;56:475–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rovinsky D, Ferguson C, Younis A, et al. Pediatric elbow dislocation associated with a Milch type I lateral condyle fracture of the humerus. J Orthop Trauma 1999;13:458–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].van Haaren ER, van Vugt AB, Bode PJ. Posterolateral dislocation of the elbow with concomitant fracture of the lateral humeral condyle: case report. J Trauma 1994;36:288–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cheng PG, Chang WN, Wang MN. Posteromedial dislocation of the elbow with lateral condyle fracture in children. J Chin Med Assoc 2009;72:103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sharma H, Sibinski M, Sherlock DA. Outcome of lateral humeral condylar mass fractures in children associated with elbow dislocation or olecranon fracture. Int Orthop 2009;33:509–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Abu-Jayyab Z, Abu-Zidan F, Marlovits S. Fracture dislocation of the lateral condyle and medial epicondyle of the humerus associated with complete radial nerve transection. J Pak Med Assoc 2011;61:920–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hendel D, Aghasi M, Halperin N. Unusual fracture dislocation of the elbow joint. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1985;104:187–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sharma H, Ayer R, Taylor GR. Complex pediatric elbow injury: an uncommon case. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2005;6:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rasool MN. Dislocations of the elbow in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86:1050–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Milch H. Fractures and fracture dislocations of the humeral condyles. J Trauma 1964;4:592–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mohan N, Hunter JB, Colton CL. The posterolateral approach to the distal humerus for open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the lateral condyle in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000;82:643–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Flynn JC, Matthews JG, Benoit RL. Blind pinning of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Sixteen years’ experience with long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974;56:263–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Roberts PH. Dislocation of the elbow. Br J Surg 1969;56:806–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Badelon O, Bensahel H, Mazda K, et al. Lateral humeral condylar fractures in children: a report of 47 cases. J Pediatr Orthop 1988;8:31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].de Jager LT, Hoffman EB. Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991;73:143–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ruo GY. Radiographic diagnosis of fracture-separation of the entire distal humeral epiphysis. Clin Radiol 1987;38:635–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mizuno K, Hirohata K, Kashiwagi D. Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis in young children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1979;61:570–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chapman VM, Grottkau BE, Albright M, et al. Multidetector computed tomography of pediatric lateral condylar fractures. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005;29:842–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pudas T, Hurme T, Mattila K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in pediatric elbow fractures. Acta Radiol 2005;46:636–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Horn BD, Herman MJ, Crisci K, et al. Fractures of the lateral humeral condyle: role of the cartilage hinge in fracture stability. J Pediatr Orthop 2002;22:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kamegaya M, Shinohara Y, Kurokawa M, et al. Assessment of stability in children's minimally displaced lateral humeral condyle fracture by magnetic resonance imaging. J Pediatr Orthop 1999;19:570–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vocke-Hell AK, Schmid A. Sonographic differentiation of stable and unstable lateral condyle fractures of the humerus in children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2001;10:138–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chapman VM, Kalra M, Halpern E, et al. 16-MDCT of the posttraumatic pediatric elbow: optimum parameters and associated radiation dose. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;185:516–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jakob R, Fowles JV, Rang M, et al. Observations concerning fractures of the lateral humeral condyle in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1975;57:430–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bhandari M, Tornetta P, Swiontkowksi MF. Group E-BOTW. Displaced lateral condyle fractures of the distal humerus. J Orthop Trauma 2003;17:306–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ganeshalingam R, Donnan A, Evans O, et al. Lateral condylar fractures of the humerus in children. Bone Joint J 2018;100-B:387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tomori Y. Anterolateral approach for lateral humeral condyle fractures in children: clinical results of a surgical treatment [in Japanese]. Orthop Surg Traumatol 2012;55:801–7. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tomori Y, Fukuuchi M, Kuroda K. Postero lateral approach for lateral humeral condyle fractures in children: clinical results of a surgical treatment using posterolateral approach [in Japanese]. Orthop Surg Traumatol 2011;54:751–5. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kurzman ID, Cheng H, MacEwen EG. Effect of liposome-muramyl tripeptide combined with recombinant canine granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on canine monocyte activity. Cancer Biother 1994;9:113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tan SHS, Dartnell J, Lim AKS, et al. Paediatric lateral condyle fractures: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018;138:809–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liu CH, Kao HK, Lee WC, et al. Posterolateral approach for humeral lateral condyle fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2016;25:153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]