Abstract

Despite possessing substantial regenerative capacity, skeletal muscle can suffer from loss of function due to catastrophic traumatic injury or degenerative disease. In such cases, engineered tissue grafts hold the potential to restore function and improve patient quality of life. Requirements for successful integration of engineered tissue grafts with the host musculature include cell alignment that mimics host tissue architecture and directional functionality, as well as vascularization to ensure tissue survival. Here we have developed biomimetic nanopatterned poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) substrates conjugated with sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a potent angiogenic and myogenic factor, to enhance myoblast and endothelial maturation. Primary muscle cells cultured on these functionalized S1P nanopatterned substrates developed a highly aligned and elongated morphology, and exhibited higher expression levels of myosin heavy chain, in addition to genes characteristic of mature skeletal muscle. We also found that S1P enhanced angiogenic potential in these cultures, as evidenced by elevated expression of endothelial-related genes. Computational analyses of live-cell videos showed a significantly improved functionality of tissues cultured on S1P-functionalized nanopatterns as indicated by greater myotube contraction displacements and velocities. In summary, our study demonstrates that biomimetic nanotopography and S1P can be combined to synergistically regulate the maturation and vascularization of engineered skeletal muscles.

Keywords: skeletal muscle, vascularization, nanotopography, sphingosine-1-phosphate, tissue engineering

The loss of skeletal muscle function and volume due to traumatic injury and myopathies such as muscular dystrophy is a significant healthcare problem for which there are currently few interventions.1–3 Tissue grafts have shown potential in animal models for restoring damaged or wasted muscles. However, autologous and allogeneic tissue grafting is often associated with detrimental effects such as donor site morbidity or long-term immunosuppression4. Likewise, although stem cell-based therapies have shown some promise for improving patient outcomes,5–7 such techniques are associated with poor survival, maturation and functional integration of transplanted cells.8–11 To address these shortcomings, tissue engineering approaches have been extensively investigated,12, 13 with the overarching goal of generating tissues in vitro that are capable of restoring function to diseased or injured muscles when engrafted in vivo.

Skeletal muscle is comprised of dense, multinucleated muscle fibers that are anisotropically oriented to allow for longitudinal contraction and force generation. As such, one of the most important requirements for engineering functional skeletal muscle tissues is the recapitulation of this highly-organized structure. Muscle extracellular matrix (ECM) architecture has been found to influence cellular behavior and processes critical for overall tissue function. Ultrastructural analysis has revealed that muscle ECM is comprised of highly aligned collagen fiber bundles that feature widths of several hundred nanometers.14, 15 Advances in micro-and nanofabrication techniques have led to the development of substrates or scaffolds that mimic these structures, and studies have shown that substrates with biomimetic nanotopographies can induce the formation of ordered muscle tissue in vitro in a physiologically-relevant manner by influencing both cellular organization and maturation.16–18

Skeletal muscle is a metabolically demanding tissue, which necessitates a high degree of vascularization. Consequently, engineered muscle should also meet this requirement, particularly if the eventual goal of generating 3D tissue constructs is to be realized. Additionally, vascularization improves cell survival upon implantation by promoting blood perfusion and in turn reducing apoptosis.19, 20 To date, most approaches for generating vascularized tissues have revolved around the use of one or multiple angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) that are delivered via scaffolds or integrated depots such as microspheres.21–25 Although significant progress has been achieved with these methods, many challenges remain. The use of angiogenic growth factors has proven to be effective at inducing vascularization, although some of these factors have been shown to repress myogenesis.26, 27 In addition, the use of recombinant growth factors can be inefficient, as their high cost may mitigate further development or their application for large scale implants.

In this study, we developed an approach for engineering vascularized and more mature skeletal muscle in which biodegradable and biomimetically nanopatterned substrates were conjugated with sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a sphingolipid G-protein-coupled receptor ligand known to have potent angiogenic and myogenic effects.28–31 Use of this small molecule agonist is advantageous for modulating both processes and obviates the need for multiple growth factors, greatly simplifying the culture platform. Substrate functionalization was achieved using 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (DOPA), a naturally-occurring amino acid derived from mussel adhesive pads.32 DOPA is capable of forming both strong ionic and covalent bonds with organic molecules through a Michael-addition type reaction without requiring harsh solvents or reagents, and is therefore a process that is likely to maintain the biological activity of S1P. It was hypothesized that the benefits of biomimetic nanotopography and sustained S1P signaling could be harnessed synergistically to induce the formation of structurally organized skeletal muscle tissues that are both mature and vascularized. This capability for generating tissues comprised of functional muscle fibers with a vascular component for nutrient delivery will serve as a promising method for developing therapeutic or investigative platforms.

Results and Discussion

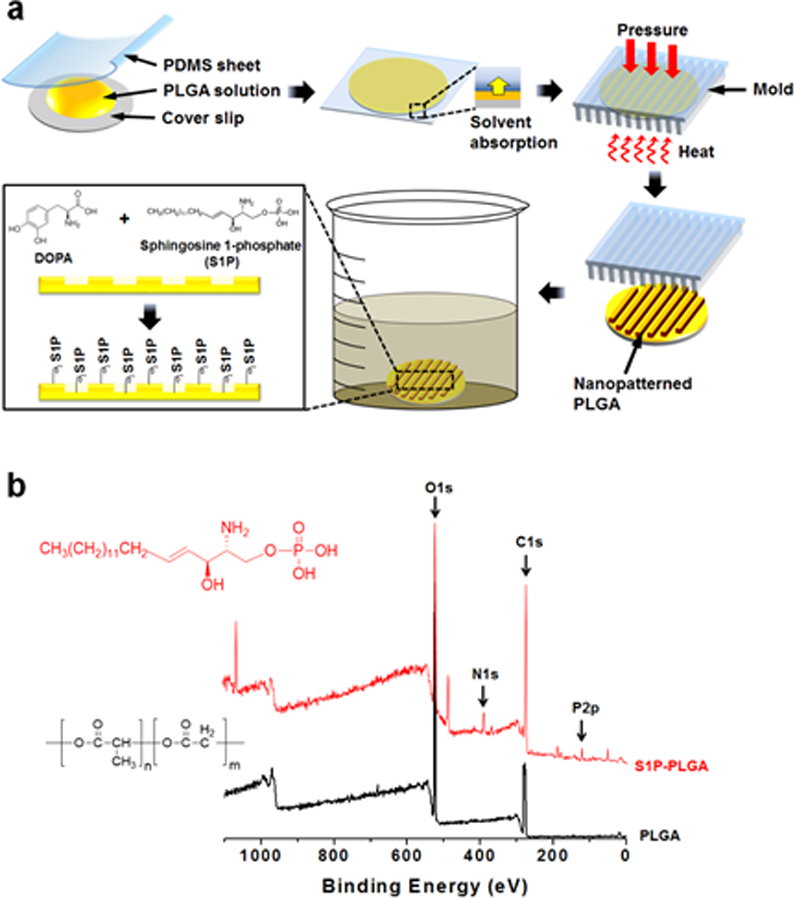

Nanopatterned PLGA substrates were fabricated using capillary force lithography (CFL), a well-established and simple method that allows for the reproducible fabrication of substrates with high-fidelity nanoscale features across centimeter length scales (Figure 1a).33 In this study, substrates featured aligned ridges and grooves that were 800 nm wide, as this nanotopography best mimicked native tissue ECM, and was previously shown to induce beneficial maturation effects on primary myoblasts.17 PLGA substrates were then placed in a solution comprised of soluble S1P and DOPA, thereby utilizing a “one-pot” functionalization scheme, the substrates could then be coated with the sphingolipid in a simple and effective manner. Surface functionalization with S1P did not negatively affect the patterned nanotopography, as scanning electron microscope (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging revealed the maintenance of high pattern fidelity (Figure S1 in Supporting Information). Additionally, successful functionalization of substrates was confirmed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), where nitrogen, phosphorous, and C-N bond peaks, characteristic of the S1P molecule, were present in conjunction with an attenuation of O-C=O and C=O bond peaks associated with the underlying PLGA (Figure 1b, Figure 2 in Supporting Information). To determine whether bound S1P would degrade over time in cell culture conditions, PLGA substrates were functionalized with fluorescein-S1P and incubated at 37°C for 10 days in PBS. PBS supernatant was collected throughout the 10-day period and their fluorescence, as well as that of the substrates at the beginning and end of the experiment, were measured using a fluorescent plate reader. It was found that substrate fluorescence was significantly greater than that of PLGA without S1P, and that their fluorescence values remained unchanged over time, while supernatant fluorescence remained at levels identical to that of ordinary PBS (Figure S3 in Supporting Information). These results are indications that the S1P attached to substrates was not significantly degrading over this timeframe and under typical cell culture conditions.

Figure 1. Fabrication and functionalization of biodegradable S1P-conjugated nanotopographically patterned substrates.

(a) PLGA is nanopatterned using capillary force lithography and functionalized with S1P with one-pot DOPA-mediated chemistry. (b) XPS analysis confirms S1P conjugation to substrate surfaces. Spectra shown is a survey scan in which nitrogen (N1s) and phosphorous (P2p) peaks characterstic of S1P appear post-functionalization (red spectra).

From a scaffold design and engineering aspect, our results provide important insights into the utilization of DOPA-mediated chemistries for functionalizing synthetic materials with bioactive ligands. In our approach, a one-pot method where S1P and DOPA were added simultaneously to the substrates was used, as opposed to a sequential deposition of a DOPA coating followed by S1P conjugation to this layer. In theory, by using the one-pot technique, S1P is better able to form conjugates with free DOPA, thereby allowing for a denser packing of S1P molecules on a substrate. While others have reported success in functionalizing surfaces using this technique with dopamine,34, 35 this study demonstrates the viability of one-pot functionalization when using DOPA. Of particular significance is the ability to utilize this technique to immobilize a lipid on a non-flat polymer-based substrate, which is a non-trivial task.36 For example, when using conventional techniques for depositing biomolecules on nanopatterned substrates, such as microcontact printing, it is often difficult to ensure that the surface coverage of both ridges and grooves is achieved. Moreover, use of this DOPA-based technique allowed for the technically-challenging functionalization of a hydrolytically-degradable polymer (PLGA) with a poorly water-soluble biomolecule (S1P) under conditions that did not adversely affect the lipid’s biological function.

Although the detailed mechanism for DOPA-mediated functionalization is still under investigation, the chemistry of catechol groups was recently demonstrated, and this mechanism may be involved in the attachment of S1P’s α-amine to PLGA’s catechol side group.37 This would allow the long acyl chain and polar headgroup of S1P to remain free to interact with S1P receptors. Specifically, the phosphonate headgroup can be surrounded by a ring of positively-charged polar residues provided by the receptor’s capping N-terminal capping helix and helices III and VII, and the acyl chain can fully extend into the receptor’s hydrophobic pocket with stable hydrophobic interactions.38, 39 Indeed, water contact angle measurements of substrates with and without S1P revealed that the functionalized substrates featured a more hydrophobic surface, with an average water contact angle of 75.34° ± 2.17°, compared to 62.54° ± 2.29° for bare PLGA (Figure S4 in Supporting Information). However, while this data is indicative of S1P acyl chain integrity, it does not exclude the possibility that some degradation of the polar headgroup still occurs.

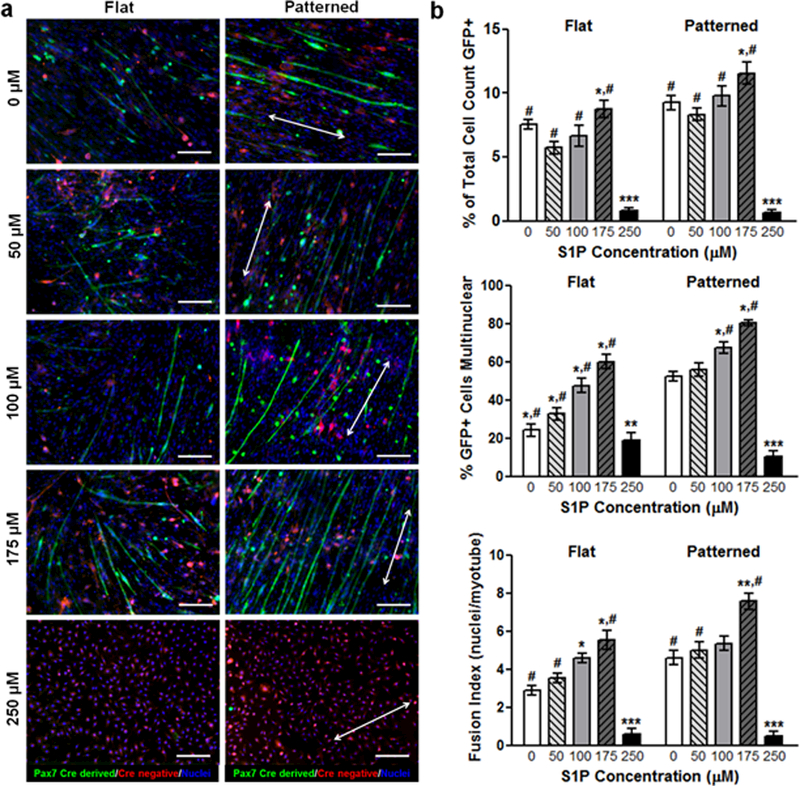

In order to distinguish myogenic cells from other populations present in skeletal muscle, we utilized the Pax7-CreERT2 allele which is definitively expressed by the majority of satellite cells.40–43 Transgenic mice harboring the Pax7-CreERT2 and mT/mG flox alleles were generated to induce irreversible labeling of Pax7 expressing myogenic cells with membrane localized GFP.44 In this dual fluorescence fate-mapping model, non-myogenic cells were distinguishable by their expression of membrane localized tdTomato. Primary muscle cells from these mice were isolated from mouse limb muscles via enzymatic digestion and seeded onto flat and patterned substrates conjugated with S1P at varying concentrations (0, 50, 100, 175, and 250 μM). Cultures were maintained for 10 days and fixed for imaging or collected for gene expression analysis. These cultures were comprised of a heterogeneous mononuclear cell population that included satellite cells and their progeny, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts. As previously observed,17 nanopatterned substrates induced a greater degree of structural organization in the form of aligned myotubes (Figure 2a). These substrates also appeared to enhance the myogenic potential of cultured progenitor cells as a greater number of GFP+ cells were observed in the patterned environment (Figure 2b). Interestingly, myogenesis appeared to be S1P dose-dependent, as myotube count peaked at 175 μM S1P. These trends also held true when examining the fusion index (number of nuclei per myotube), with topography and S1P imparting a synergistic effect on myotube formation as a result of myoblast fusion. However, S1P at the highest concentration of 250 μM appeared to have a detrimental effect on myogenesis, as GFP+ cell count and fusion index decreased sharply on both flat and patterned substrates under this condition. To further examine the maturation of the engineered muscle tissue, cultures of primary muscle cells from wild-type (WT) mice were stained for myosin heavy chain type I (MHC), an isoform of slow MHC expressed by mature muscles.45 A significantly greater number of MHC-I+ myotubes was observed on patterned substrates versus flat with most S1P concentrations. The greatest number of differentiated myotubes observed on patterned substrates was also with 175 μM of S1P, followed by a sharp decrease at 250 μM S1P (Figure 3a, b).

Figure 2. S1P signaling and nanotopographical cues induce greater myogenic potential of cultured primary satellite cells and myoblasts.

(a) Representative fluorescent images of cells and myotubes that are Pax7+ (green), which identifies them as either progeny of differentiated myogenic progenitor cells, or are progenitors themselves. Scale bars: 50 µm; direction of nanopatterning indicated by white double arrows. (b) Quantitative analyses of Pax7-GFP imaging for indicators of active myogenesis and myotube development. All quantitative data are presented as means ± SEM, n≥10 different cultures. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (comparing groups within substrate topography; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc); #p < 0.05 (comparing flat vs. patterned at the same S1P concentration; Student’s t-test).

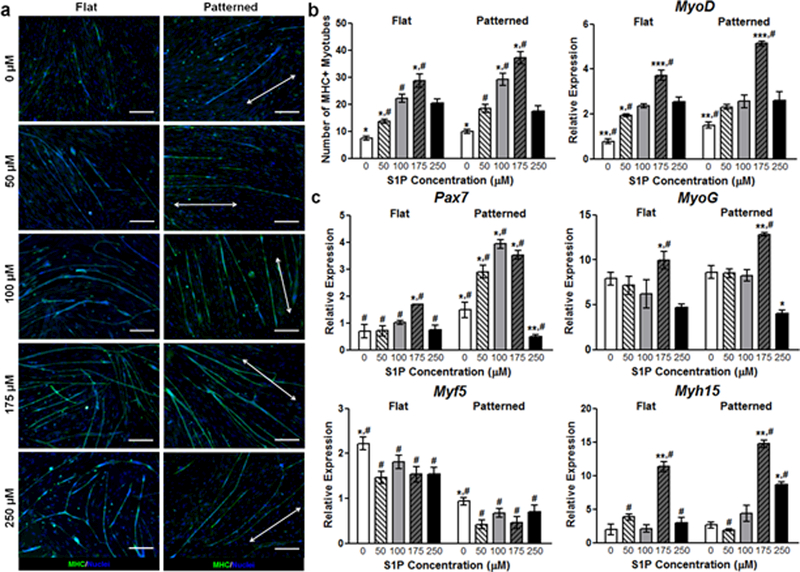

Figure 3. S1P signaling and nanotopographical cues enhance the maturation of differentiated muscle cells.

(a) Representative images of myotubes stained for MHC (pseudo-color in green). Scale bars: 50 µm; direction of nanopatterning indicated by white double arrows. (b) Images were analyzed for the total number of MHC+ myotubes, with the greatest number seen on nanopatterned substrates functionalized with 175 µM S1P. (c) qRT-PCR analyses of primary muscle cells cultured on substrates for 10 days. Genes examined are markers representative of progenitor activation (Pax7) and various stages of myogenic differentiation, ranging from immature (Myf5) to more mature (MyoD, MyoG, Myh15). All quantitative data are presented as means ± SEM, n≥10 different cultures. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (comparing groups within substrate topography; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc); #p < 0.05 (comparing flat vs. patterned at the same S1P concentration; Student’s t-test).

Subsequently, we analyzed the transcriptional profile of myogenic regulatory factors to understand the mechanisms of S1P on myotube maturation that occurred in a dose-dependent manner. The relative expression levels in cultured cells of several genes that spanned the spectrum of myogenic development were quantified using quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analyses (Figure 3c). As aforementioned, Pax7 plays a critical role in the proper function of satellite cells and is therefore a well-established indicator of immature skeletal precursors (satellite cells). Examination of this gene revealed a significantly greater expression level in cells cultured on patterned substrates as compared to their flat substrate counterparts, regardless of S1P concentration. S1P-mediated expression also appeared to follow the previously observed biphasic trend. However, for patterned substrates, relative expression peaks at 100 μM S1P, rather than at 175 μM. In contrast to Pax7, which is specific for undifferentiating muscle precursors that can self-renew, Myf5 is expressed in differentiating myoblasts and immature myocytes46–48. We observed that cells cultured on flat substrates exhibited greater expression levels of this gene compared to those cultured on patterned substrates, with no apparent differences due to S1P. The expression of MyoD, MyoG (myogenin) and Myh15 (myosin heavy chain 15), which are expressed in late-stage or terminally differentiated muscle cells,49, 50 was greater in cells not only on patterned substrates, but also significantly in cells on substrates with 175 μM S1P, regardless of underlying topography (Figure 3c). Since a peak in expression of markers for more mature cells at 175 μM S1P was observed, it is plausible that this increase in maturation led to a corresponding lower expression of Pax7 at this concentration of S1P. In all examined genes, there was a drastic decrease in expression levels in cells cultured on substrates functionalized with 250 μM of S1P.

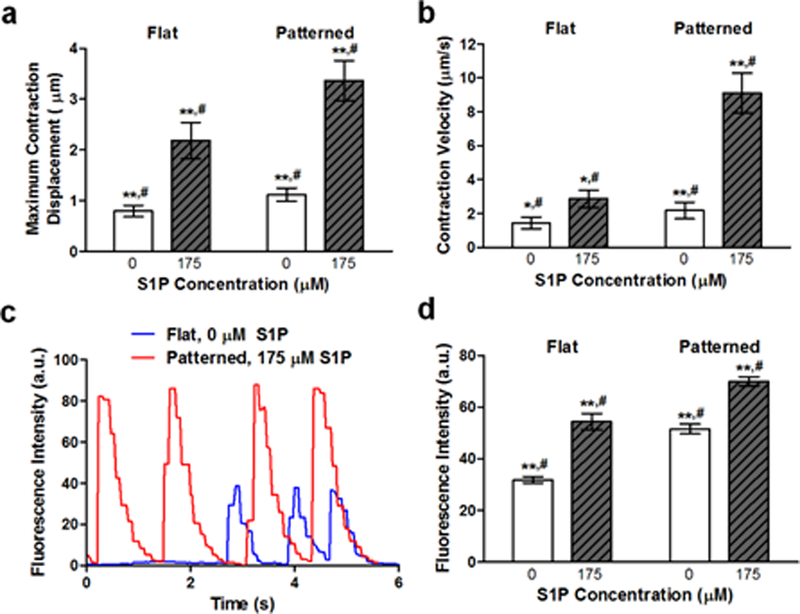

Although the enhancement of myogenesis and maturation of the engineered skeletal muscle cultures was demonstrated with the aforementioned analyses, molecular markers of myogenesis are not direct indicators of muscle function. Thus, experiments were conducted to determine whether the maturation observed due to synergistic signaling from S1P and nanopatterning translated to improvements in myotube function. Using a correlation-based contraction quantification (CCQ) MATLAB script developed by our lab,51 bright-field microscopy videos of contracting myotubes were analyzed. The maturation effects of biomimetic nanopatterning led to a corresponding improvement in myotube function, as myotubes on these substrates featured an average contraction displacement of 1.11 ± 0.13 µm, while those on flat substrates had an average contraction displacement of 0.79 ± 0.11 µm. Myotubes on nanopatterned substrates functionalized with 175 μM S1P exhibited an average contraction displacement of 3.37 ± 0.39 µm, while those cultured on functionalized flat substrates had an average displacement of 2.18 ± 0.36 µm (Figure 4a). The addition of S1P led to a significant increase in displacement values for myotubes on both flat and patterned topographies, although patterning still led to a functional maturation advantage. A similar trend was observed in regard to the contraction velocities of myotubes, where significant increases occurred when nanotopography and S1P were present. Representative of the two ends of the spectrum, myotubes on nanopatterned substrates functionalized with 175 μM S1P had an average contraction velocity of 9.11 ± 1.18 µm/s, while myotubes on non-functionalized flat substrates had an average contraction velocity of 1.44 ± 0.34 µm/s (Figure 4b).

Figure 4. Enhanced myogenic maturation leads to improved skeletal muscle tissue function.

(a) The average contraction displacement of myotubes on flat or patterned substrates with and without 175 μM S1P. The combination of patterning and S1P led to the largest displacements. (b) The average contraction velocity of myotubes on flat or patterned substrates with and without 175 μM S1P. Myotubes developed from cells on patterned substrates functionalized with S1P contracted with the greatest velocities. (c) Representative traces of fluorescence intensity over time for myotubes on flat (blue) and nanopatterned substrates with 175 μM S1P (red) illustrating their respective contractile regularity. (d) Average fluorescence intensities of contracting GCaMP-expressing myotubes on flat or patterned substrates with and without 175 μM S1P. All quantitative data are presented as means ± SEM, n≥10 different cultures. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (comparing groups within substrate topography; Student’s t-test); #p < 0.05 (comparing flat vs. patterned at the same S1P concentration; Student’s t-test).

S1P and nanotopography effects on myotube Ca2+ handling capabilities were examined by generating transgenic mice in which Pax7CreERT2 expressing cells and their progeny would express GCaMP3, a well-characterized GFP-based calcium indicator for imaging Ca2+ dynamics in cells.52, 53 Once more, primary muscle cells were cultured on flat and patterned substrates with and without 175 μM S1P and imaged after 10 days with fluorescence live cell microscopy. Myotubes that had formed from these GCaMP3-expressing progenitor cells were observed to fluoresce as they spontaneously contracted (Videos 1 & 2 in Supporting Information), and the fluorescence intensity of these myotubes was tracked and plotted over time. Interestingly, the contractile rhythm of myotubes differed based on culture conditions, where those on flat substrates contracted irregularly, while those on nanopatterned substrates with S1P exhibited more regular and consistent contractions (Figure 4c). Quantification of the average fluorescence intensities revealed that myotubes cultured with S1P on nanopatterned substrates exhibited significantly greater levels of fluorescence corresponding to calcium ion flux, and thus an indication of improved calcium handling (Figure 4d). Combined, the results of contraction and calcium dynamics analyses show that the increased expression of skeletal muscle maturation markers due to the combination of topographical and S1P signaling cues led to a corresponding enhancement of the engineered tissue’s functional capabilities.

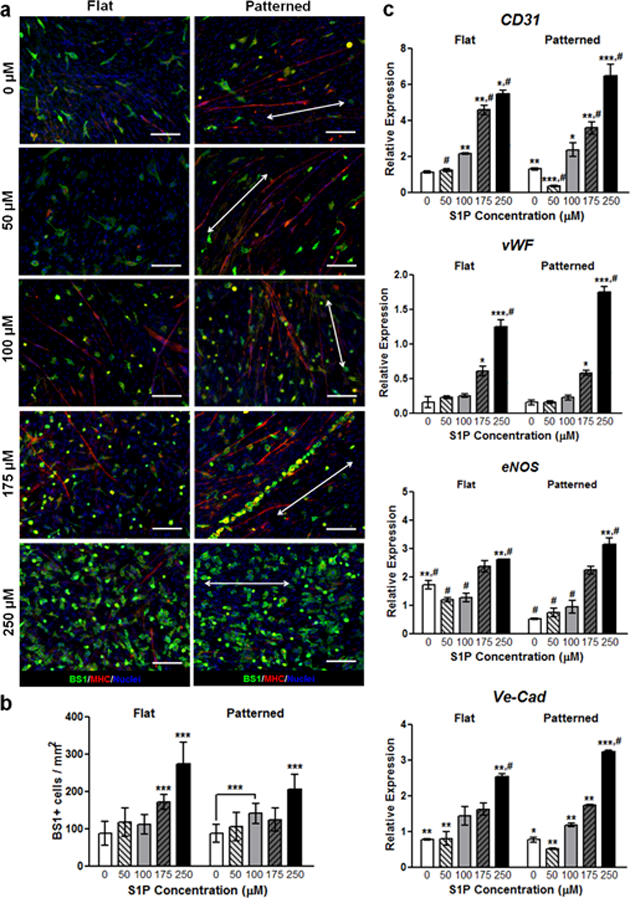

Primary cell cultures from wild-type mice were simultaneously stained with BS1 lectin, an endothelial cell marker54 (green), and MHC (red) to examine the neovascularization potential of S1P-functionalized substrates (Figure 5a). The potency of S1P as angiogenic factor was observed with increasing concentrations corresponding to a greater number of BS1+ cells, regardless of topography. In contrast to myogenic indicators that peaked with 175 µM of S1P, the number of BS1+ cells was greatest with 250 μM of S1P (Figure 5b). On some of the 175 μM patterned substrates, BS1+ cells appeared to organize themselves along the axis of myotubes. To confirm that the dose dependent increase of BS1+ cells corresponded with a presence of active endothelial cells, we examined the transcription levels of angiogenic markers. The expression of genes related to endothelial adhesion (PECAM, CD31), function (von Willebrand factor, vWF), integrity (VE-cadherin, Ve-Cad), and vascular tone regulation (endothelial nitric oxide synthase, eNOS) were assessed quantitatively (Figure 5c). A correlation between S1P concentration and detection of endothelial transcripts was observed, with the greatest and most significant expression levels found in cells cultured on substrates functionalized with 250 μM S1P. In general, topography did not appear to play a significant role in regulating vascularization, although qualitatively alignment of vascular cells with myotubes was only observed on patterned substrates.

Figure 5. S1P induces endothelial cell differentiation and enhanced pre-vascularization in a dose-dependent manner.

(a) Staining for BS1 (pseudo-green), an endothelial cell marker, shows significantly greater numbers of BS1+ cells on substrates with S1P, regardless of underlying nanotopography. Interestingly, some endothelial cells appear to localize around formed myotubes (pseudo-red). Scale bars: 50 μm; direction of nanopatterning indicated by white double arrows. (b) Quantification of BS1 staining, with the greatest number of positively-stained cells present on 250 µM S1P-functionalized substrates. (c) qRT-PCR assays show an increased expression of endothelial cell (CD31) and vascular development markers (vWF, eNOS, Ve-Cad) with respect to increasing S1P concentration. All quantitative data are presented as means ± SEM, n≥10 different cultures. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (comparing groups within substrate topography; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc); #p < 0.05 (comparing flat vs. patterned at the same S1P concentration; Student’s t-test).

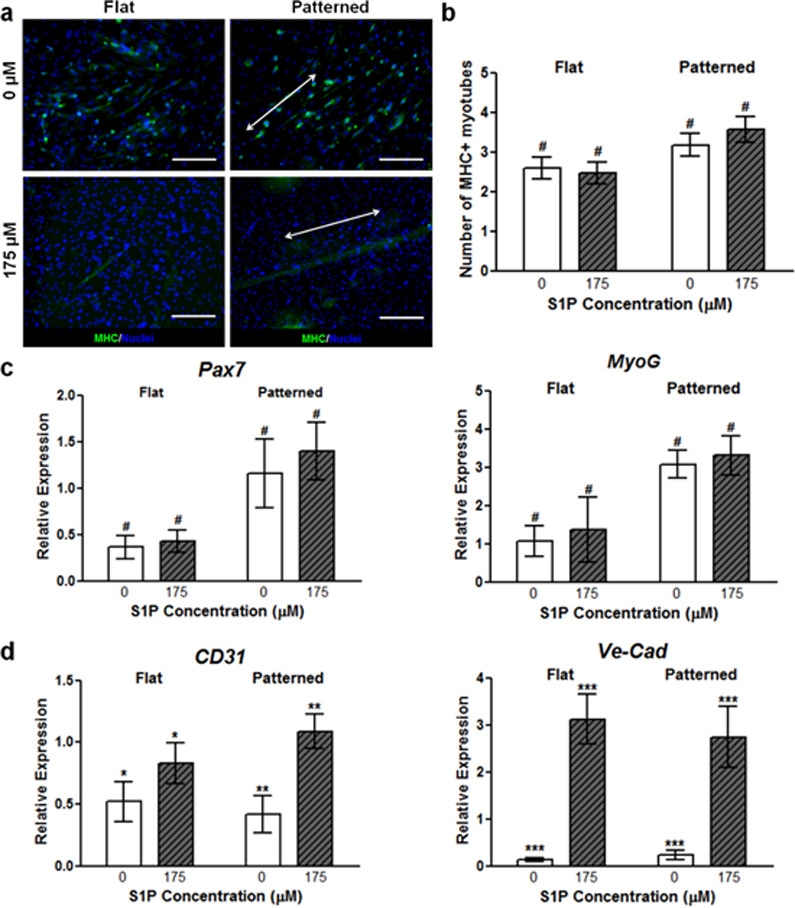

To gain insight on the molecular mechanism by which S1P, in combination with nanotopography, modulates myogenesis, we examined the role of S1P receptor 1 (S1P1) in myogenic cells. Although S1P signaling in skeletal musculature is highly complex and confers a variety of functions that are mediated mainly by S1P receptors 1 through 3,55 S1P1 was chosen due to it being the most highly expressed in satellite cells during skeletal muscle regeneration, as well as in primary myoblasts cultured on nanopatterned substrates functionalized with 175 μM S1P (Figure S5 in Supporting Information).56, 57 We employed tamoxifen inducible genetic deletion of S1P1 specifically in satellite cells by utilizing Pax7CreERT2 mice that were homozygous for the S1P1 flox allele.58 To validate the effectiveness of the Cre-lox gene ablation, primary muscle cells from these and WT mice were cultured onto flat and patterned substrates functionalized with either no S1P or with 175 μM S1P for 10 days. Using qRT-PCR analysis, it was found that the expression of S1P1 was significantly reduced in cells from Pax7CreERT+/− x S1P1 flox+/+ mice (Table S1 in Supporting Information). Staining for MHC in myotubes formed from these cells revealed no significant difference in expression despite the presence of S1P, while patterned substrates induced greater expression of this protein compared to flat substrates (Figure 6a, b). Furthermore, quantitative genetic analysis also revealed that topographical cues were still able to upregulate Pax7 and MyoG expression, while S1P did not (Figure 6c). Since S1P1 was only knocked out in the myogenic cells that would eventually differentiate and form myotubes, the effects of S1P on endothelial cell maturation should be maintained. This was confirmed with qRT-PCR analysis of markers for vascular development (CD31, Ve-Cad), which showed significant upregulation independent of substrate topography when these cells were exposed to S1P (Figure 6d).

Figure 6. Flox-out of S1P1 results in predominantly nanotopography-mediated myogenic differentiation and maturation.

(a) There is no significant difference in the number of MHC+ myotubes when comparing functionalization states in S1P1 flox-out cultures. However, myotube formation and alignment is still enhanced by nanopatterning. Scale bars: 100 μm; direction of nanopatterning indicated by white double arrows. (b) Quantification of MHC staining further illustrates the lack of S1P-induced myogenic maturation. (c) qRT-PCR of representative genetic markers for myogenesis, where marker expression is increased in the presence of biomimetic nanotopgraphy, but not in the presence of S1P. (d) Gene marker analysis of markers for endothelial cells and vascular integrity illustrate continued effect of S1P on non-myogenic cells. All quantitative data are presented as means ± SEM, n≥10 different cultures. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (comparing groups within substrate topography; Student’s t-test); #p < 0.05 (comparing flat vs. patterned at the same S1P concentration; Student’s t-test).

The significance of sphingolipids and the extent of their signaling has yet to be fully elucidated,59 and S1P in particular has been found to play a role in the regulation of a variety of critical cell processes, such as division, survival, migration, and adhesion,60–63 with recent studies suggesting that S1P is also involved in skeletal muscle regeneration. Under homeostatic conditions, low circulation concentrations of S1P (~ 2 µM) can be found in mammalian plasma; however, upon focal muscle injury, plasma S1P levels can increase by up to 50%.64 There are strong indications that this increase in S1P synthesis and subsequent availability as a circulating ligand in response to injury is required to mediate the migration, activation, and entry of satellite cells into the cell cycle in order to differentiate and form new muscle.30, 31, 56, 65 Our results appear to support these findings, as myogenic progenitor activation and differentiation significantly improved as S1P concentration increased, with a functionalization concentration of 175 µM eliciting a peak response. The finding of a larger presence of Pax7+ cells present on patterned substrates conjugated with this concentration of S1P suggests that there is a greater induction of immature myoblast proliferation, or perhaps that there is a stable population of progenitor cells present that would enable the long-term differentiation and restoration of lost or damaged tissue. At the same time, lower expression levels of Myf5 on patterned substrates, regardless of S1P, is an indication that in addition to the maintenance or recapitulation of the satellite cell niche, biomimetic nanotopographies also induce those cells that do become activated to readily differentiate towards the formation of mature skeletal muscle tissue. However, the expression of genes and proteins indicative of late stage myogenic maturation once again increased with S1P, and this corresponded with improved tissue function in the form of increased myotube contraction displacement and velocity, which can be translated to an increase in contractile force. The irregularity of the spontaneous contractions observed in myotubes on flat substrates versus those on functionalized patterned substrates is a further indication of the improved contractile machinery development due to nanotopographical and S1P signaling. The improved Ca2+ handling of myotubes on functionalized nanopatterned substrates is also a sign of tissue maturation attributed to enhanced myogenic development due to S1P, as S1P has been shown to increase intracellular calcium levels,66 with calcium in turn acting as a mediator of myoblast differentiation.67

By mimicking the nanotopographical cues that would normally be seen by myoblasts and satellite cells in vivo, our aim was to recapitulate signaling cascades that would lead to improved functional maturation. While the role of specific mechanotransduction pathways in this process is still being elucidated, it has been demonstrated that Rho GTPases involved in cytoskeletal reorganization positively regulate MyoD expression and skeletal muscle differentiation.68 It has also been found that in myoblastic cells, cytoskeletal remodeling and the formation of stress fibers promote the opening of stretch-activated channels and the subsequent increase in Ca2+ influx.69, 70 This is reflected in the data shown in Figure 4, and since Ca2+ is an important second messenger for skeletal muscle differentiation, this is another potential mechanism for nanotopography-mediated maturation. Studies have also suggested that the PI3K/Akt pathway is involved in contact guidance and mechanotransduction signaling, and that activation of this pathway leads to skeletal muscle hypertrophy and myogenesis.71, 72 The benefits of biomimetic nanotopography is perhaps most apparent in the S1P1 flox-out experiments where nanotopographical cues were still able to induce myotube formation, cellular alignment, and upregulated expression of late-stage maturation muscle maturation markers, even as the myogenic effects of S1P were being mitigated. It is possible that as part of the downstream effects of this mechanotransduction signaling, S1P is produced and secreted by the myogenic cells themselves via sphingosine kinases to induce S1P-mediated effects downstream.65 To investigate this further, the relative expression levels of sphingosine kinase 1 (Sphk1), sphingosine kinase 2 (Sphk2), and sphingosine phosphatase 1 (Sgpp1) in both primary murine muscle cells and C2C12 myoblasts cultured on flat and patterned substrates with and without S1P were analyzed. With the exceptions of an upregulation of Sphk1 in primary myoblasts on substrates with no S1P and an upregulation of Sgpp1 in C2C12 myoblasts on patterned substrates with S1P, no other significant differences in expression levels were observed (Figure S6 in Supporting Information). The results suggest that kinase activity and S1P synthesis is unaffected by nanotopographical cues, and that in some cases, the lack of exogenous S1P induces an increase in the production of endogenous S1P. Furthermore, if the bulk of the maturation responses observed in this study were due to endogenously-formed S1P, we should expect to see similar levels of expression of maturation markers and functional capabilities in all cultures in which nanopatterning was present. Instead, we see a significant upregulation of these markers in addition to improvements in myotube function at higher concentrations of exogenous substrate-bound S1P. These results are thus an indication that there is a synergistic effect on functional maturation that is achieved when cells are subjected to both S1P signaling and nanotopographical cues, and that this effect is greatly enhanced by the S1P-functionalized nanopatterned substrates utilized in this study.

While the most effective concentration of S1P for muscle maturation in this study was found to be orders of magnitude greater than physiological levels, this may be a function of a situation in which the presented ligands are bound to a substrate, rather than being freely available in solution as it is the case in vivo. This could in fact provide an additional benefit when these muscle sheets are implanted. As the biodegradable substrates are broken down over time, bound S1P would be released locally and induce prolonged regeneration that would further enhance tissue development and function, even in dystrophic muscles.57

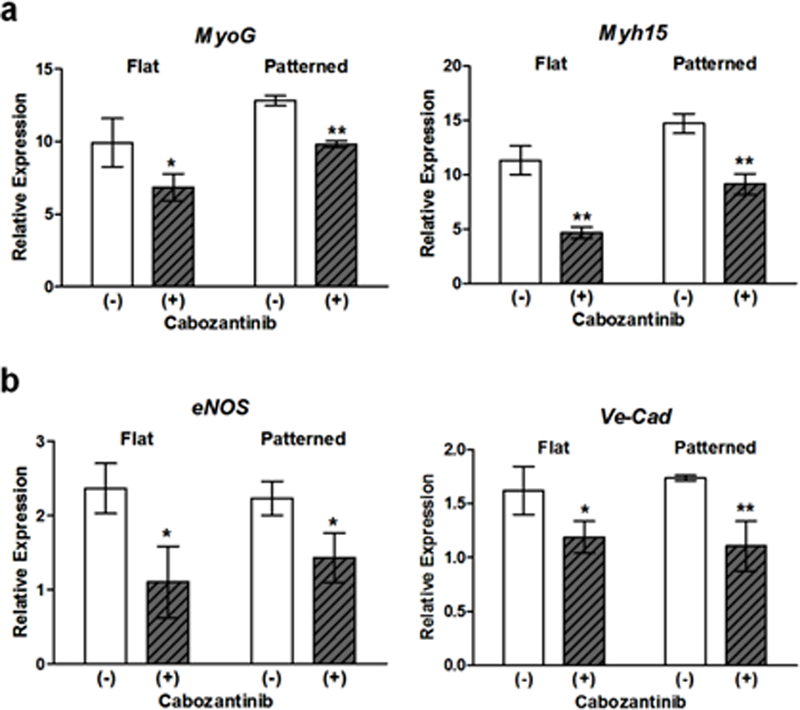

In addition to inducing myogenic differentiation, S1P signaling has long been acknowledged to play a key role in vascular development and angiogenesis. Specifically, it has been shown by others that vascular endothelial cells cultured with S1P exhibited increased motility, eNOS enzyme activity, and cell barrier integrity, leading to a corresponding increase in tube formation over time.28, 73–75 Additionally, disruption of S1P signaling in vivo results in blood flow dysregulation and vascular leakage due to junctional destabilization resulting from VE-cadherin mislocalization.58, 76, 77 These pro-vascularization effects were also seen in this study with the increased expression of genetic markers for not only endothelial cell maturity, but also for vessel formation and stabilization. Furthermore, once implanted, the presence of S1P could also induce the migration of endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells present in the host tissue to the implantation site and contribute to the formation of neovessels.29, 78 In addition to the long-term functional and survival benefits of generating vascularized skeletal muscle tissues, the presence of mature endothelial cells can also assist with myogenic development, since the secretion of VEGF from these cells has been shown to stimulate myotube hypertrophy and further improve myogenic differentiation.79 Differentiating myogenic cells also secrete VEGF, and this could induce pronounced localized angiogenesis, thus creating a positive feedback loop in which reciprocal interaction between these two cell types can support continued angio-myogenesis.80 This is perhaps best illustrated by the close juxtaposition of endothelial cells with myotubes present on nanopatterned substrates functionalized with 175 µM, which was shown to induce the greatest degree of myogenic differentiation and maturation. Indeed, when cells were cultured on flat and patterned substrates functionalized with 175 µM S1P were fed with media supplemented with 5 µM of cabozantinib (XL184), a potent VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) inhibitor, markers for late-stage and terminal skeletal muscle maturation (MyoG, Myh15) were downregulated in comparison to cultures without VEGFR2 inhibition (Figure 7a). However, these markers were more expressed in cells cultured on nanopatterned substrates than in cells on flat substrates, indicating that mechanotransduction cues were still exerting an effect. Meanwhile, the expression of markers of vascular endothelial maturation (eNOS, Ve-Cad) was significantly downregulated in cultures with cabozantinib (Figure 7b). Taken together, these results suggest that inhibiting VEGF function in these co-cultures reduces the benefits of engineering an environment in which mutually beneficial maturation can occur as it does in vivo.

Figure 7. Inhibition of VEGFR2 in cells cultured on substrates functionalized with 175 µM S1P results in reduced skeletal muscle and endothelial maturation.

(a) Expression of markers for late-stage or terminal differentiation were significantly downregulated in comparison to cells in which VEGFR2 function was uninhibited. (b) Expression markers for vascular endothelial maturation were significantly downregulated in the presence of cabozantinib. All quantitative data are presented as means ± SEM, n=6 different cultures. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

Interestingly, it was observed that there was an apparent biphasic dependence of myogenesis on S1P concentration, and that this trend did not carry over to vascular development. In fact, at the highest concentration tested (250 µM), the number of myoblasts and myogenic progenitors were greatly reduced in number and some even appeared to be apoptotic. Ceramide, a metabolite of S1P that is produced by the conversion of sphingosine via ceramide synthases (CerS), is generally associated with growth arrest and cell death.81–83 Since this conversion is reversible, it has been proposed that it is the relative levels of these two lipid signaling molecules in response to external stimuli that determines cell fate, and thus acts as a “sphingolipid rheostat”.83, 84 Therefore, with the production of a large amount of ceramide at 250 µM S1P, this balance may have been shifted towards a pro-apoptotic state in myoblasts, thereby negating the beneficial myogenic effects of S1P. Immunostaining of cultures at this concentration of S1P for cleaved caspase-3, a marker for apoptosis, revealed that the percentage of apoptotic cells is in fact significantly greater than in controls (Figure S7 in Supporting Information). However, it has been found that the activity of ceramide synthase 2 (CerS2) is inhibited by S1P, and that the distribution of CerS2 is greatest in highly-vascularized organs such as the liver and kidney.85 It is then plausible that this inhibited activity of CerS2 in the cultured endothelial cells decreases the conversion rate of S1P to ceramide, and thus maintains the pro-angiogenic response of these cells to increased S1P stimulation. To further explore this hypothesis, primary cells were sorted into myoblast and endothelial cell populations before being cultured on substrates functionalized with 250 µM S1P and subsequently immunostained for ceramide and CerS2. In addition to displaying a more apoptotic morphology, ceramide accumulation was found to be significantly greater in myoblasts than in endothelial cells. At the same time, CerS2 expression was found to be greater in endothelial cells which correlates with other findings in literature (Figure S8 in Supporting Information).86 This data thus suggests that the inhibition of this specific synthase in endothelial cells is indeed helping with the shifting of the sphingolipid rheostat away from the overwhelming ceramide synthesis and resulting apoptosis seen in the myogenic cell population.

Conclusions

While the capabilities of biomimetic nanotopographies on inducing cellular maturation have been reported on previously,17, 87 the incorporation of the sphingolipid S1P as a ligand for simultaneously enhancing both the myogenic and neovascularization potential of cultured cells is an important aspect of this work. The resulting tissues were structurally ordered, and at higher S1P concentrations, were comprised of numerous differentiated and contracting myotubes, along with a sub-population of Pax7-expressing muscle precursors. Additionally, the increased expression levels of endothelial markers in these tissues is an indication of in vitro vascular development and improved potential for tissue integration and survival. In future work, by utilizing cell-sheet fabrication techniques that enable the generation of highly-ordered 3D tissues in a scaffold-free manner88 and subsequently culturing these multi-layered constructs in the presence of S1P, it would be possible to create 3D skeletal muscle tissues that are primed for continued myogenic development and vascularization once implanted in vivo. Aside from their potential application as a form of implantable therapy for treating chronic or traumatic skeletal muscle loss, tissues generated using the techniques reported herein can also be considered as an effective in vitro platform for further characterizing the molecular mechanisms behind muscle development, as well as for disease modeling or drug screening.

Methods

Substrate Fabrication.

Flat and nanopatterned substrates were generated using a capillary force lithography (CFL) technique that has been detailed previously17. Briefly, polyurethane acrylate (PUA; Minuta Technology, Korea), and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184, Dow Corning, MI, USA) were first prepared to form the molds and solvent-absorbing sheets, respectively. PUA molds were fabricated by first dispensing PUA precursor onto a patterned silicon wafer master which had been made using standard photolithography techniques, and lightly pressing a polyethylene terephthalate (PET, Skyrol®, SKC Inc., Korea) film (thickness = 75 μm) against the PUA. The PUA precursor spontaneously filled the cavities of the master mold by means of capillary action and was cured by exposure to UV light (λ = 250–400 nm) for approximately 30 s (dose = 100 mJ/cm2).After this initial curing, the PUA mold was peeled off from the substrate and further exposed to UV light overnight for complete curing. PDMS sheets were made by first combining polymer precursor and curing agent at a mixing ratio of 10:1 and cured at 60°C for 10 hrs before manually cutting prior to use.

To generate the substrates used in this study, a 100 μL drop of 15% w/v PLGA (MW: 50,000 – 75,000, 50:50 lactide:glycolide ratio, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) dissolved in chloroform was dispensed onto a clean glass coverslip, and a PDMS sheet was placed on top of the polymer solution. Slight pressure (~10 kPa) was applied evenly on the PDMS for 5 min before the sheet was removed. The PLGA-coated coverslip was then placed onto a hot plate preheated to 120ºC for 5 min to allow any residual solvent to evaporate. A nanopatterned PUA mold was then placed on top with constant pressure (~100 kPa) applied for 15 min before the entire assembly was removed from heat and allowed to cool to room temperature. The mold was carefully peeled off and the nanopatterned PLGA substrate is stored under desiccation until ready for use. For this study, substrates with 800 × 800 × 600 nm (groove width x ridge width x groove depth) feature sizes were used. Flat PLGA substrates were fabricated by skipping the patterning steps, and were also stored under desiccation.

Substrate Functionalization with S1P.

Fabricated PLGA substrates were functionalized with sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P; Cayman Chemical, MI, USA) or fluorescein-S1P (Echelon Biosciences, UT, USA) using 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (DOPA; Sigma Aldrich). A 2 mg/mL working solution of was generated by dissolving DOPA in 10 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris; Fisher Scientific, NH, USA) buffer with a pH of 8.5. DOPA working solution was combined with a 500 μM S1P stock solution for each sample to achieve the appropriate S1P concentration. Samples were then incubated at room temperature overnight on a rocker. Afterwards, the DOPA-S1P solution was aspirated and substrates were washed three times with PBS before being dried using nitrogen gas. Substrates not functionalized with S1P were incubated with DOPA only.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

S1P-functionalized nanopatterned substrates were sputter-coated with Au/Pd alloy prior to imaging, which was accomplished using a scanning electron microscope (Sirion XL30, FEI, OR, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM).

An atomic force microscope (Dimension Icon-PT, Bruker, MA, USA) was used to measure the topography of nanopatterned substrates post-functionalization. The AFM was operated in non-contact mode with scan frequency of 0.5 Hz, and images were taken in 256 × 256 pixel resolution over a 10 µm × 10 µm area.

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS).

All XPS spectra were taken using a Surface Science Instruments S-probe spectrometer, and peak areas were determined using Service Physics ESCA2000A Analysis Software. X-ray spot size was approximately 800 µm, and pass energy for survey and high-resolution spectra was 150 eV and 50 eV, respectively. The take-off angle was approximately 55º, which translates to a sampling depth of approximately 50 Å. Three spots were analyzed on each PLGA sample (bare and functionalized).

Water Contact Angle Measurements.

A 10 µL droplet of diH2O was deposited onto substrates with DOPA and DOPA+S1P. Droplets were imaged and their contact angles with the substrates measured using a goniometer (FTA200, First Ten Ångstroms, VA, USA). Six samples of each group were used for these measurements.

Transgenic Mouse Generation.

For all experiments in which primary muscle cells from transgenic mice were used, we utilized mice harboring the tamoxifen-inducible knock-in/knock-out Pax7CreERT2 allele89. These were mated with mice homozygous for the mT/mG flox, heterozygous for the GCamP3 flox, and homozygous for the S1P1 receptor to generate each respective Cre-lox system44, 53, 58. Reporter mice required only one generation to produce genotypes of Pax7CreERT+/− x mT/mG+/− or Pax7CreERT+/− x GCamP3+/−. Pax7CreERT+/− x S1P1 flox+/+ mice were achieved within 3 generations by crossing F1 Pax7CreERT+/− x S1P1 flox+/− with unrelated S1P1 flox+/+ animals. All mouse models were acquired from Jackson labs with the following catalog numbers: 012476, 007575, 014538, and 019141. Genotyping was accomplished using 1–2 mm tail clips that per collected and frozen in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes at −20ºC until ready for processing. Genomic DNA was extracted by boiling tail snips at 95°C in 75 µL of 50 mM NaOH for approximately 1 hr, with vortexing every 15 minutes. Reactions were then neutralized by adding 25 µL 1M tris-HCl pH 6.8 and then samples were centrifuges at 13,000 g for 2 mins. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was conducted using 1 µL of template from our extraction buffer in a final reaction of 20 µL with the Bioline 2x Master mix following the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer pairs and polymerase reaction parameters are listed in Table S2 in Supporting Information. NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publication #85–23 Rev. 1985) were observed throughout this study.

Cell Isolation and Culture.

Hind limb muscle mononuclear cells used in culture were isolated as previously described17, 90. Briefly, three days prior to tissue harvesting, the tibialis anterior (TA), gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles of both limbs in each mouse were injected with a 10 nM solution of cardiotoxin (CTX) from Naja mossambica (Sigma Aldrich) dissolved in water. TA were injected with 50 µL, and gastrocnemius and quadriceps were injected with 100 µL each. Mice were sacrificed 3 days post-injury at the peak of satellite cell activation following CTX injury. The timing of collection was chosen to enrich mononuclear cell isolations with myogenic cells that are otherwise a minority in these skeletal muscles. Previous characterization of cells obtained using this isolation protocol have revealed that of the non-hematopoietic cell types, approximately 32% and 35% were comprised of myogenic and endothelial cells, respectively. The remainder of the cell population was comprised of fibroblasts and other non-myogenic cell types.90, 91 Injured muscles were harvested under sterile conditions and cleaned of any fat and tendons and then digested in a buffer containing both collagenase type IV and dispase II (Worthington Biochemical, NJ, USA) for a total of 45 min at 37°C. Cell/tissue mixtures were then transferred to warmed F10 medium (Hyclone, PA, USA) supplemented with 15% horse serum to inhibit enzyme digestion. The mixture was then passed sequentially through cell strainers with 70 µm and 40 µm mesh sizes to remove debris, muscle fibers, and multinucleated cells. Collected mononuclear cells were then seeded onto each respective substrate at a density of 50,000 cells/cm2. Cells were maintained in F10 medium supplemented with 2 µM CaCl2, 15% horse serum, and 20 ng/mL mouse basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and media was changed every 4th day of culture. For induction of Cre-lox knock-in/knock-out in cells from transgenic mice, media was further supplemented for the first 4 days of culture with 20 µg/mL 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma Aldrich). For vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) inhibition studies, media was supplemented with 5 µM cabozantinib (XL184; Selleck Chemicals, TX, USA) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting.

Isolated primary cells were resuspended in PBS with 1% BSA and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated mouse antibodies for CD31, CD34, CD45, α7 integrin, and Sca1 for 60 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then washed and resuspended in PBS with 2% PBS before being sorted into myogenic and endothelial cell populations as previously described.90 Briefly, cells that were CD31+/CD45− were sorted as endothelial cells, while cells that were CD31−/Sca1−/CD34+/α7+ were sorted as myogenic cells.

Immunostaining and Fluorescence Microscopy.

Cultures for imaging were fixed at day 10 with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature before permeation with 0.1% Triton-X for 10 minutes. For myosin heavy chain staining, myotubes were incubated overnight at 4°C with purified mouse IgG against myosin heavy chain type I (1:100, BA-D5, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, deposited by Schiaffino, S.), then with rabbit anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 (1:500 for 1 hour at room temperature). For endothelial cell identification, FITC-conjugated BS1 (1:500 for 1 hour at room temperature, Sigma-Aldrich) was utilized to stain cells for imaging. Staining for apoptosis was achieved using an antibody for cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA) diluted at 1:200. Antibodies for ceramide (Sigma Aldrich) and CerS2 (Boster Biological Technology, CA, USA) were also used at a 1:200 dilution for staining and imaging. F-actin was stained using Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen, CA, USA). All secondary antibodies were utilized at a 1:500 dilution. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Invitrogen). Stained cells were then imaged using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 widefield fluorescence microscope. Quantitative analysis of images was accomplished using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, MD, USA), and were conducted by two blinded researchers independently.

Gene Expression Quantification.

After 10 days of culture, RNA from approximately 1 × 106 cells cultured cells was collected from 10 different cultures using the E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I (Omega Bio-Tek, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantity and purity of RNA was determined by 260/280nm absorbance. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1μg of RNA using the high capacity cDNA synthesis kit from Applied Biosystems (CA, USA) per manufacturer’s protocols using a randomized primer. The relative expression levels of selected genes were obtained using quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analyses. cDNA of cultured cells in different condition (10ng) was prepared using the Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR master mix (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). Reactions were processed by the ABI 7900HT PCR system with the following parameters: 50°C/2min and 95°C/10min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C/15s and 60°C/1min. Results were analyzed using SDS 2.3 software, and relative expression was calculated using the comparative Ct method. Each sample was run in triplicate reactions for each gene. To examine myogenic differentiation and myogenic potential, Pax7, Myf5, MyoD, MyoG (myogenin), and Myh15 were used as markers, while CD31, Ve-Cad, vWF, and eNOS were used as markers for the vascular differentiation of endothelial cells. Primers for the myogenic regulatory factors Pax7, Myf5, MyoD and MyoG were as previously reported89. Primers used for the vascular related genes CD31, Ve-Cad, vWF, and eNOS were also as previously reported92. Primer pairs for Myh15 were designed in-house and were (5’-TGA GCC TAA GAA AAA GCT GGG-3’, forward) and (5’-CCA AAA CGC GAA GAG TTG TCA-3’, reverse). For validation of the S1P1 flox-out mouse model, primers used for assessing the expression of this receptor were as previously reported.93 Primers for Sphk1, Sphk2, Sgpp1, S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., and used as supplied. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene and conventional tissue culture polystyrene substrates with no S1P were used as a control in all analyses.

Calcium Imaging and Analysis.

Fluorescent live cell videos at 20X magnification and an excitation wavelength of 488 nm were taken of contracting GCaMP+ myotubes. Videos were analyzed for fluorescence intensity using ImageJ. Peak fluorescence values from contracting myotubes were averaged for each condition across at least 20 fields of view. Videos were captured using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 widefield fluorescence microscope.

Correlation-based Contraction Quantification (CCQ).

Bright-field videos of contracting myotubes obtained at 20X magnification were analyzed using a custom MATLAB (MathWorks, MA, USA) script for CCQ that utilizes particle image velocimetry (PIV) and digital image correlation (DIC) algorithms51. In brief, an initial reference video frame is established and divided into a grid of windows of a set size. Each of these windows is run through a correlation algorithm with a subsequent frame, and any displacement that occurs between frames is converted into a vector map. This map provides contraction angles, and when spatially averaged, contraction magnitudes and velocities. A Gaussian correlation peak with a probabilistic nature is used in the correlation equation, providing sub-pixel accuracy. The bright-field videos analyzed using CCQ were captured using a Nikon TS100 microscope at 30 frames per second.

Statistical Analyses.

All quantitative data is presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons method was used to analyze data sets that include more than two experimental groups, while a Student’s t-test was used to compare data sets looking at only two variables. In all analyses, a p value less than 0.05 was considered significant and n was defined by the number of discrete cultured substrates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R21AR064395 and R01NS094388 (to D.-H. K.), and Muscular Dystrophy Association grants MDA 255907 (to D.-H. K.) and MDA 277543 (to M. R.). This work was also supported by a University of Washington Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging Genetic Approaches to Aging Training Grant Fellowship T32AG000057 (to N. I.), and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute/University of Washington Molecular Medicine Scholarship (to J. H. T.). The authors would like to thank Dr. Dan Graham at the University of Washington’s National ESCA and Surface Analysis Center for Biomedical Problems (NESAC/BIO; NIH P41EB002027) for his assistance with the XPS analysis of functionalized substrates. The authors would also like to thank Eve Byington and Austin Chen for their technical assistance in this study.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Topographical characterization (SEM and AFM) of nanopatterned substrates post-functionalization; high-resolution carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus XPS scans of S1P-functionalized substrates; fluorescence measurements of functionalized substrates and supernatant over 10 days’ incubation; water contact angle measurements of functionalized and non-functionalized substrates; representative live-cell fluorescent videos of contracting myotubes; expression of S1P1 in cells from Pax7CreERT+/− x S1P1 flox+/+ mice relative to those from wild-type mice; representative images of cultures stained for cleaved caspase-3 and quantification; representative images of cultures stained for ceramide and CerS2; primer sequences used for genotyping the transgenic mouse lines generated for this study. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army Medical Department, Department of the Army, Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

References

- 1.Kalyani RR; Corriere M; Ferrucci L, Age-Related and Disease-Related Muscle Loss: The Effect of Diabetes, Obesity, and Other Diseases. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014, 2, 819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puthucheary ZA; Rawal J; McPhail M; Connolly B; Ratnayake G; Chan P; Hopkinson NS; Phadke R; Dew T; Sidhu PS; Velloso C; Seymour J; Agley CC; Selby A; Limb M; Edwards LM; Smith K; Rowlerson A; Rennie MJ; Moxham J; Harridge SD; Hart N; Montgomery HE, Acute Skeletal Muscle Wasting in Critical Illness. J. Am. Med. Assoc 2013, 310, 1591–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacKenzie EJ; Jones AS; Bosse MJ; Castillo RC; Pollak AN; Webb LX; Swiontkowski MF; Kellam JF; Smith DG; Sanders RW; Jones AL; Starr AJ; McAndrew MP; Patterson BM; Burgess AR, Health-Care Costs Associated with Amputation or Reconstruction of a Limb-Threatening Injury. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 2007, 89, 1685–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muramatsu K; Doi K; Kawai S, The Outcome of Neurovascularized Allogeneic Muscle Transplantation Under Immunosuppression with Cyclosporine. J. Reconstr. Microsurg 1994, 10, 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins CA; Olsen I; Zammit PS; Heslop L; Petrie A; Partridge TA; Morgan JE, Stem Cell Function, Self-Renewal, and Behavioral Heterogeneity of Cells from the Adult Muscle Satellite Cell Niche. Cell 2005, 122, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montarras D; Morgan J; Collins C; Relaix F; Zaffran S; Cumano A; Partridge T; Buckingham M, Direct Isolation of Satellite Cells for Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Science 2005, 309, 2064–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacco A; Doyonnas R; Kraft P; Vitorovic S; Blau HM, Self-Renewal and Expansion of Single Transplanted Muscle Stem Cells. Nature 2008, 456, 502–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burdzinska A; Gala K; Kowalewski C; Zagozdzon R; Gajewski Z; Paczek L, Dynamics of Acute Local Inflammatory Response After Autologous Transplantation of Muscle-Derived Cells into the Skeletal Muscle. Mediators Inflamm 2014, 2014, 482352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosgrove BD; Sacco A; Gilbert PM; Blau HM, A Home Away from Home: Challenges and Opportunities in Engineering in vitro Muscle Satellite Cell Niches. Differentiation 2009, 78, 185–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan Y; Maley M; Beilharz M; Grounds M, Rapid Death of Injected Myoblasts in Myoblast Transfer Therapy. Muscle Nerve 1996, 19, 853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu Z; Balkir L; van Deutekom JC; Robbins PD; Pruchnic R; Huard J, Development of Approaches to Improve Cell Survival in Myoblast Transfer Therapy. J. Cell Biol 1998, 142, 1257–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qazi TH; Mooney DJ; Pumberger M; Geissler S; Duda GN, Biomaterials Based Strategies for Skeletal Muscle Tissue Engineering: Existing Technologies and Future Trends. Biomaterials 2015, 53, 502–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bach AD; Beier JP; Stern-Staeter J; Horch RE, Skeletal Muscle Tissue Engineering. J. Cell Mol. Med 2004, 8, 413–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillies AR; Lieber RL, Structure and Function of the Skeletal Muscle Extracellular Matrix. Muscle Nerve 2011, 44, 318–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillies AR; Chapman MA; Bushong EA; Deerinck TJ; Ellisman MH; Lieber RL, High Resolution Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of Fibrotic Skeletal Muscle Extracellular Matrix. J. Physiol 2017, 595, 1159–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juhas M; Engelmayr GC Jr.; Fontanella AN; Palmer GM; Bursac N, Biomimetic Engineered Muscle with Capacity for Vascular Integration and Functional Maturation in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2014, 111, 5508–5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang HS; Ieronimakis N; Tsui JH; Kim HN; Suh KY; Reyes M; Kim DH, Nanopatterned Muscle Cell Patches for Enhanced Myogenesis and Dystrophin Expression in a Mouse Model of Muscular Dystrophy. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1478–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi JS; Lee SJ; Christ GJ; Atala A; Yoo JJ, The Influence of Electrospun Aligned Poly(epsilon-caprolactone)/Collagen Nanofiber Meshes on the Formation of Self-Aligned Skeletal Muscle Myotubes. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2899–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auger FA; Gibot L; Lacroix D, The Pivotal Role of Vascularization in Tissue Engineering. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2013, 15, 177–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levenberg S; Rouwkema J; Macdonald M; Garfein ES; Kohane DS; Darland DC; Marini R; van Blitterswijk CA; Mulligan RC; D’Amore PA; Langer R, Engineering Vascularized Skeletal Muscle Tissue. Nat. Biotechnol 2005, 23, 879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson TP; Peters MC; Ennett AB; Mooney DJ, Polymeric System for Dual Growth Factor Delivery. Nat. Biotechnol 2001, 19, 1029–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borselli C; Ungaro F; Oliviero O; d’Angelo I; Quaglia F; La Rotonda MI; Netti PA, Bioactivation of Collagen Matrices Through Sustained VEGF Release from PLGA Microspheres. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 92A, 94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demirdogen B; Elcin AE; Elcin YM, Neovascularization by bFGF Releasing Hyaluronic Acid-Gelatin Microspheres: in vitro and in vivo Studies. Growth Factors 2010, 28, 426–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karal-Yilmaz O; Serhatli M; Baysal K; Baysal BM, Preparation and in vitro Characterization of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)-Loaded Poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) Microspheres Using a Double Emulsion/Solvent Evaporation Technique. J. Microencapsul 2011, 28, 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen RR; Silva EA; Yuen WW; Mooney DJ, Spatio-Temporal VEGF and PDGF Delivery Patterns Blood Vessel Formation and Maturation. Pharm. Res 2007, 24, 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olwin BB; Rapraeger A, Repression of Myogenic Differentiation by aFGF, bFGF, and K-FGF is Dependent on Cellular Heparan Sulfate. J. Cell Biol 1992, 118, 631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pena TL; Chen SH; Konieczny SF; Rane SG, Ras/MEK/ERK Up-Regulation of the Fibroblast KCa Channel FIK is a Common Mechanism for Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor and Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Suppression of Myogenesis. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 13677–13682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee OH; Kim YM; Lee YM; Moon EJ; Lee DJ; Kim JH; Kim KW; Kwon YG, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Induces Angiogenesis: Its Angiogenic Action and Signaling Mechanism in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1999, 264, 743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y; Wada R; Yamashita T; Mi Y; Deng CX; Hobson JP; Rosenfeldt HM; Nava VE; Chae SS; Lee MJ; Liu CH; Hla T; Spiegel S; Proia RL, Edg-1, the G Protein-Coupled Receptor for Sphingosine-1-Phosphate, is Essential for Vascular Maturation. J. Clin. Invest 2000, 106, 951–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagata Y; Partridge TA; Matsuda R; Zammit PS, Entry of Muscle Satellite Cells into the Cell Cycle Requires Sphingolipid Signaling. J. Cell Biol 2006, 174, 245–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rapizzi E; Donati C; Cencetti F; Nincheri P; Bruni P, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Differentially Regulates Proliferation of C2C12 Reserve Cells and Myoblasts. Mol. Cell. Biochem 2008, 314, 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H; Scherer NF; Messersmith PB, Single-Molecule Mechanics of Mussel Adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103, 12999–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suh KY; Park MC; Kim P, Capillary Force Lithography: A Versatile Tool for Structured Biomaterials Interface Towards Cell and Tissue Engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater 2009, 19, 2699–2712. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang SM; Hwang NS; Yeom J; Park SY; Messersmith PB; Choi IS; Langer R; Anderson DG; Lee H, One-Step Multipurpose Surface Functionalization by Adhesive Catecholamine. Adv. Funct. Mater 2012, 22, 2949–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kailasa SK; Wu HF, One-Pot Synthesis of Dopamine Dithiocarbamate Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles for Quantitative Analysis of Small Molecules and Phosphopeptides in SALDI-and MALDI-MS. Analyst 2012, 137, 1629–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair PM; Salaita K; Petit RS; Groves JT, Using Patterned Supported Lipid Membranes to Investigate the Role of Receptor Organization in Intercellular Signaling. Nat. Protoc 2011, 6, 523–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song IT; Lee M; Lee H; Han J; Jang JH; Lee MS; Koh GY; Lee H, PEGylation and HAylation via Catechol: α-Amine-Specific Reaction at N-terminus of Peptides and Proteins. Acta Biomater 2016, 43, 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosen H; Stevens RC; Hanson M; Roberts E; Oldstone MB, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate and Its Receptors: Structure, Signaling, and Influence. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2013, 82, 637–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Sullivan C; Dev KK, The Structure and Function of the S1P1 Receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2013, 34, 401–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seale P; Sabourin LA; Girgis-Gabardo A; Mansouri A; Gruss P; Rudnicki MA, Pax7 is Required for the Specification of Myogenic Satellite Cells. Cell 2000, 102, 777–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Maltzahn J; Jones AE; Parks RJ; Rudnicki MA, Pax7 is Critical for the Normal Function of Satellite Cells in Adult Skeletal Muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, 16474–16479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zammit PS; Relaix F; Nagata Y; Ruiz AP; Collins CA; Partridge TA; Beauchamp JR, Pax7 and Myogenic Progression in Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells. J. Cell Sci 2006, 119, 1824–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lepper C; Partridge TA; Fan CM, An Absolute Requirement for Pax7-Positive Satellite Cells in Acute Injury-Induced Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Development 2011, 138, 3639–3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muzumdar MD; Tasic B; Miyamichi K; Li L; Luo L, A Global Double-Fluorescent Cre Reporter Mouse. Genesis 2007, 45, 593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torgan CE; Daniels MP, Regulation of Myosin Heavy Chain Expression During Rat Skeletal Muscle Development in vitro. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 1499–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Francetic T; Li Q, Skeletal Myogenesis and Myf5 Activation. Transcription 2011, 2, 109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooper RN; Tajbakhsh S; Mouly V; Cossu G; Buckingham M; Butler-Browne GS, In vivo Satellite Cell Activation via Myf5 and MyoD in Regenerating Mouse Skeletal Muscle. J. Cell Sci 1999, 112, 2895–2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunther S; Kim J; Kostin S; Lepper C; Fan CM; Braun T, Myf5-Positive Satellite Cells Contribute to Pax7-Dependent Long-Term Maintenance of Adult Muscle Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 590–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagers AJ; Conboy IM, Cellular and Molecular Signatures of Muscle Regeneration: Current Concepts and Controversies in Adult Myogenesis. Cell 2005, 122, 659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossi AC; Mammucari C; Argentini C; Reggiani C; Schiaffino S, Two Novel/Ancient Myosins in Mammalian Skeletal Muscles: MYH14/7b and MYH15 Are Expressed in Extraocular Muscles and Muscle Spindles. J. Physiol 2010, 588, 353–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macadangdang J; Guan X; Smith AS; Lucero R; Czerniecki S; Childers MK; Mack DL; Kim DH, Nanopatterned Human iPSC-based Model of a Dystrophin-Null Cardiomyopathic Phenotype. Cell. Mol. Bioeng 2015, 8, 320–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borges-Pereira L; Campos BR; Garcia CR, The GCaMP3 - A GFP-Based Calcium Sensor for Imaging Calcium Dynamics in the Human Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum. MethodsX 2014, 1, 151–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zariwala HA; Borghuis BG; Hoogland TM; Madisen L; Tian L; De Zeeuw CI; Zeng H; Looger LL; Svoboda K; Chen TW, A Cre-Dependent GCaMP3 Reporter Mouse for Neuronal Imaging in vivo. J. Neurosci 2012, 32, 3131–3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalka C; Masuda H; Takahashi T; Kalka-Moll WM; Silver M; Kearney M; Li T; Isner JM; Asahara T, Transplantation of ex vivo Expanded Endothelial Progenitor Cells for Therapeutic Neovascularization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2000, 97, 3422–3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Danieli-Betto D; Peron S; Germinario E; Zanin M; Sorci G; Franzoso S; Sandona D; Betto R, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Signaling is Involved in Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Am. J. Physiol., Cell Physiol 2010, 298, C550–C558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Calise S; Blescia S; Cencetti F; Bernacchioni C; Donati C; Bruni P, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Stimulates Proliferation and Migration of Satellite Cells: Role of S1P Receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ieronimakis N; Pantoja M; Hays AL; Dosey TL; Qi J; Fischer KA; Hoofnagle AN; Sadilek M; Chamberlain JS; Ruohola-Baker H; Reyes M, Increased Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Improves Muscle Regeneration in Acutely Injured mdx Mice. Skelet. Muscle 2013, 3, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allende ML; Yamashita T; Proia RL, G-Protein-Coupled Receptor S1P1 Acts Within Endothelial Cells to Regulate Vascular Maturation. Blood 2003, 102, 3665–3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blaho VA; Hla T, An Update on the Biology of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptors. J. Lipid Res 2014, 55, 1596–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spiegel S; Milstien S, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate: An Enigmatic Signalling Lipid. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2003, 4, 397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hla T, Physiological and Pathological Actions of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 2004, 15, 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aarthi JJ; Darendeliler MA; Pushparaj PN, Dissecting the Role of the S1P/S1PR Axis in Health and Disease. J. Dent. Res 2011, 90, 841–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hannun YA; Obeid LM, Principles of Bioactive Lipid Signalling: Lessons from Sphingolipids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2008, 9, 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loh KC; Leong WI; Carlson ME; Oskouian B; Kumar A; Fyrst H; Zhang M; Proia RL; Hoffman EP; Saba JD, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Enhances Satellite Cell Activation in Dystrophic Muscles Through a S1PR2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway. PLoS One 2012, 7, e37218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sassoli C; Formigli L; Bini F; Tani A; Squecco R; Battistini C; Zecchi-Orlandini S; Francini F; Meacci E, Effects of S1P on Skeletal Muscle Repair/Regeneration During Eccentric Contraction. J. Cell. Mol. Med 2011, 15, 2498–2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meacci E; Cencetti F; Formigli L; Squecco R; Donati C; Tiribilli B; Quercioli F; Zecchi Orlandini S; Francini F; Bruni P, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Evokes Calcium Signals in C2C12 Myoblasts via Edg3 and Edg5 Receptors. Biochem. J 2002, 362, 349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Porter GA Jr.; Makuck RF; Rivkees SA, Reduction in Intracellular Calcium Levels Inhibits Myoblast Differentiation. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277, 28942–28947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Travaglione S; Messina G; Fabbri A; Falzano L; Giammarioli AM; Grossi M; Rufini S; Fiorentini C, Cytotoxic Necrotizing Factor 1 Hinders Skeletal Muscle Differentiation in vitro by Perturbing the Activation/Deactivation Balance of Rho GTPases. Cell Death Differ 2005, 12, 78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Formigli L; Meacci E; Sassoli C; Chellini F; Giannini R; Quercioli F; Tiribilli B; Squecco R; Bruni P; Francini F; Zecchi-Orlandini S, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Induces Cytoskeletal Reorganization in C2C12 Myoblasts: Physiological Relevance for Stress Fibres in the Modulation of Ion Current Through Stretch-Activated Channels. J. Cell Sci 2005, 118, 1161–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Benavides Damm T; Egli M, Calcium’s Role in Mechanotransduction During Muscle Development. Cell. Physiol. Biochem 2014, 33, 249–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lai KM; Gonzalez M; Poueymirou WT; Kline WO; Na E; Zlotchenko E; Stitt TN; Economides AN; Yancopoulos GD; Glass DJ, Conditional Activation of Akt in Adult Skeletal Muscle Induces Rapid Hypertrophy. Mol. Cell. Biol 2004, 24, 9295–9304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Briata P; Lin WJ; Giovarelli M; Pasero M; Chou CF; Trabucchi M; Rosenfeld MG; Chen CY; Gherzi R, PI3K/AKT Signaling Determines a Dynamic Switch Between Distinct KSRP Functions Favoring Skeletal Myogenesis. Cell Death Differ 2012, 19, 478–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garcia JG; Liu F; Verin AD; Birukova A; Dechert MA; Gerthoffer WT; Bamberg JR; English D, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Promotes Endothelial Cell Barrier Integrity by Edg-Dependent Cytoskeletal Rearrangement. J. Clin. Invest 2001, 108, 689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee MJ; Thangada S; Claffey KP; Ancellin N; Liu CH; Kluk M; Volpi M; Sha’afi RI; Hla T, Vascular Endothelial Cell Adherens Junction Assembly and Morphogenesis Induced by Sphingosine-1-Phosphate. Cell 1999, 99, 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Igarashi J; Michel T, S1P and eNOS Regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1781, 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jung B; Obinata H; Galvani S; Mendelson K; Ding BS; Skoura A; Kinzel B; Brinkmann V; Rafii S; Evans T; Hla T, Flow-Regulated Endothelial S1P Receptor-1 Signaling Sustains Vascular Development. Dev. Cell 2012, 23, 600–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gaengel K; Niaudet C; Hagikura K; Lavina B; Muhl L; Hofmann JJ; Ebarasi L; Nystrom S; Rymo S; Chen LL; Pang MF; Jin Y; Raschperger E; Roswall P; Schulte D; Benedito R; Larsson J; Hellstrom M; Fuxe J; Uhlen P; Adams R; Jakobsson L; Majumdar A; Vestweber D; Uv A; Betsholtz C, The Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor S1PR1 Restricts Sprouting Angiogenesis by Regulating the Interplay Between VE-Cadherin and VEGFR2. Dev. Cell 2012, 23, 587–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu F; Verin AD; Wang P; Day R; Wersto RP; Chrest FJ; English DK; Garcia JG, Differential Regulation of Sphingosine-1-Phosphate-and VEGF-Induced Endothelial Cell Chemotaxis. Involvement of Gi α 2-Linked Rho Kinase Activity. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 2001, 24, 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bryan BA; Walshe TE; Mitchell DC; Havumaki JS; Saint-Geniez M; Maharaj AS; Maldonado AE; D’Amore PA, Coordinated Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression and Signaling During Skeletal Myogenic Differentiation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 994–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Christov C; Chretien F; Abou-Khalil R; Bassez G; Vallet G; Authier FJ; Bassaglia Y; Shinin V; Tajbakhsh S; Chazaud B; Gherardi RK, Muscle Satellite Cells and Endothelial Cells: Close Neighbors and Privileged Partners. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 1397–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hannun YA; Obeid LM, The Ceramide-Centric Universe of Lipid-Mediated Cell Regulation: Stress Encounters of the Lipid Kind. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277, 25847–25850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kolesnick R, The Therapeutic Potential of Modulating the Ceramide/Sphingomyelin Pathway. J. Clin. Invest 2002, 110, 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hait NC; Oskeritzian CA; Paugh SW; Milstien S; Spiegel S, Sphingosine Kinases, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate, Apoptosis and Diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1758, 2016–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cuvillier O; Pirianov G; Kleuser B; Vanek PG; Coso OA; Gutkind S; Spiegel S, Suppression of Ceramide-Mediated Programmed Cell Death by Sphingosine-1-Phosphate. Nature 1996, 381, 800–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Laviad EL; Albee L; Pankova-Kholmyansky I; Epstein S; Park H; Merrill AH Jr.; Futerman AH, Characterization of Ceramide Synthase 2: Tissue Distribution, Substrate Specificity, and Inhibition by Sphingosine 1-Phosphate. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 5677–5684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Berdyshev EV; Gorshkova I; Skobeleva A; Bittman R; Lu X; Dudek SM; Mirzapoiazova T; Garcia JGN; Natarajan V, FTY720 Inhibits Ceramide Synthases and Up-regulates Dihydrosphingosine 1-Phosphate Formation in Human Lung Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem 2009, 284, 5467–5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carson D; Hnilova M; Yang X; Nemeth CL; Tsui JH; Smith AS; Jiao A; Regnier M; Murry CE; Tamerler C; Kim DH, Nanotopography-Induced Structural Anisotropy and Sarcomere Development in Human Cardiomyocytes Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 21923–21932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]