Abstract

Objectives Neck metastases in patients with esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB) constitute the most significant predictor of poor long-term survival. Recently, researchers discovered the existence of dural lymphatic channels that drain to the cervical lymph nodes. From this physiologic basis, we hypothesized that patients with ENB who develop dural invasion (DI) would exhibit a proclivity for neck metastases.

Design Retrospective review.

Setting Tertiary referral center.

Participants All patients treated for ENB from January 1, 1994 to December 31, 2015.

Main Outcome Measures Incidence, laterality, and recurrence rate of neck metastases by DI status.

Results Sixty-one patients were identified (38% female; median age 49, range, 10–80), 34 (56%) of whom had DI and 27 (44%) did not. Of patients with DI, 50% presented with or developed neck disease following treatment compared with just 22% of those without DI ( p = 0.026). Bilateral neck disease was more common in patients with DI (11/34, 32%) compared with those without (2/27, 7%) ( p = 0.018). Five-year regional recurrence-free survival rates were 88% for those without and 64% for those with DI ( p = 0.022). Kadish C patients with DI were more likely to develop regional recurrence when compared with Kadish C without DI and Kadish A/B ( p = 0.083). Further, Kadish C patients with DI displayed worse overall survival than Kadish C without DI and Kadish A/B. Kadish D patients displayed the worst overall survival. The difference in overall survival among these four groups was significant ( p < 0.001).

Conclusion DI by ENB is associated with increased incidence of cervical nodal metastases, bilateral neck disease, worse regional recurrence-free survival, and poorer overall survival. These data support the division of Kadish C by DI status.

Keywords: esthesioneuroblastoma, olfactory neuroblastoma, dural invasion, elective neck treatment, neck metastases

Introduction

Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB) is an uncommon sinonasal malignancy thought to arise from the olfactory epithelium of the cribriform plate. 1 Comprising up to 6% of all sinonasal neoplasms, initial diagnosis of ENB is often delayed due to nonspecific symptomatology, such as epistaxis and nasal obstruction, and overall disease rarity. 2 As a result, patients frequently develop advanced local disease that progresses to neck disease. 3 Importantly, neck metastases with ENB constitute the most significant predictor of poor survival outcomes for patients. 4 5

In 2015, Louveau et al discovered the existence of dural lymphatic channels that drain to the cervical lymph nodes. 6 Aspelund et al subsequently confirmed their discovery and showed that unilateral dural lesions preferentially drained to the ipsilateral side. 6 7 These novel findings form the physiologic basis from which this study was envisioned. In an attempt to elucidate which patients with ENB are at greatest risk for developing neck disease, we hypothesized that patients with dural invasion (DI) would exhibit a proclivity for neck metastases. Secondarily, because ENB comprises a midline neoplasm that does not unilaterally invade the dura, we hypothesized that patients with DI would be more likely to develop bilateral cervical nodal metastases when compared with patients who developed neck disease but never displayed DI by ENB.

Methods

Patient Data

After receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board, we conducted a retrospective analysis of all patients with ENB treated at our institution from January 1, 1994 to December 31, 2015. In each case, the operative and pathology reports were used to determine DI status. Histological confirmation and Hyams' grading of tumors were performed by a neuropathologist from our institution. 8 Tumor staging utilized the modified Kadish staging system. 9 Neck metastases were identified by clinical or radiographic involvement and confirmed by needle aspiration or by nodal dissection.

Statistical Methods

Continuous features were summarized with medians, interquartile ranges (IQRs), and ranges; categorical features were summarized with frequency counts and percentages. Associations of demographic and clinical features between patients with and without DI were evaluated using Spearman's rank correlation, Kruskal–Wallis, Wilcoxon rank sum, and chi-square tests. Regional recurrence-free survival, local recurrence-free survival, recurrence-free survival, and overall survival were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared among groups using log-rank tests. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States). All tests were two-sided and p -values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and Treatment Data

A total of 61 patients were identified, including 34 (56%) with DI and 27 (44%) without DI. Demographic and clinical data for the cohort by DI status are presented in Table 1 . Sample sizes for features with missing data are indicated in italics in parentheses. There were 12 (20%) patients with Kadish A/B, 11 (18%) with Kadish C without DI, 27 (44%) with Kadish C with DI, and 11 (18%) with Kadish D disease at diagnosis. All but four Kadish D patients displayed involvement of the dura. Eleven (32%) of the patients with DI had positive margins, three of whom developed regional recurrence. Given the trend toward higher Hyams' grading in patients with DI ( Table 1 ), Hyams' grade and its association with neck disease was examined, and higher Hyams' grade was not associated with primary neck disease ( p = 0.25) or regional recurrence-free survival ( p = 0.52).

Table 1. Comparison of clinical and demographical features by dural invasion (DI) status ( N = 61) .

| Without DI N = 27 |

With DI N = 34 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | Median (IQR; Range) | p -Value | |

| Age at diagnosis in years | 44 (36–51; 10–80) | 52 (40–60; 22–73) | 0.071 |

| Charlson index ( N = 54 ) | 2 (2–3; 2–8) | 3 (2–4; 2–9) | 0.085 |

| Sex | N (%) | ||

| Female | 14 (52) | 9 (26) | 0.042 |

| Male | 13 (48) | 25 (74) | |

| Race/ethnicity ( N = 58 ) | |||

| All others | 3 (12) | 2 (6) | 0.65 |

| White | 23 (88) | 30 (94) | |

| Grade ( N = 49 ) | |||

| Low | 12 (57) | 9 (32) | 0.086 |

| Intermediate | 2 (10) | 3 (11) | |

| High | 7 (33) | 16 (57) | |

| Primary local treatment | |||

| Surgery alone | 11 (41) | 2 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery + RT | 8 (30) | 13 (38) | |

| Surgery + RT + CT | 4 (15) | 18 (53) | |

| Surgery + CT | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| RT + CT | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | |

| RT alone | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| Elected no treatment | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| Primary management of the neck | |||

| ND + RT for pN1 | 3 (11) | 3 (9) | 0.77 |

| RT alone for pN1 | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| ND alone for pN1 | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| ENI for cN0 | 2 (7) | 2 (6) | |

| ND for cN + pN0 | 0 | 2 (6) | |

| Positive margins ( N = 57 ) | 0 | 11 (33) | 0.001 |

| Kadish stage | |||

| A | 2 (7) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| B | 10 (37) | 0 | |

| C | 11 (41) | 27 (79) | |

| D | 4 (15) | 7 (21) | |

Abbreviations: c, clinical; CT, chemotherapy; ENI, elective neck irradiation; IQR, interquartile range; N, cervical nodal involvement (0 = negative, 1 = positive); ND, neck dissection; p, pathological; RT, radiotherapy.

Note: Sample sizes for features with missing data are indicated in italics in parentheses.

Patients with DI were significantly more likely to receive combination therapy comprised of craniofacial resection plus adjuvant radiation with or without adjuvant chemotherapy for primary treatment of ENB ( p < 0.001; Table 1 ). Of patients who received surgery, 40 patients underwent open craniofacial resection (24 of whom with DI), 9 underwent endoscopic resection (3 of whom with DI), and 8 underwent combined endoscopic and craniofacial resection (6 of whom with DI).

Of the 11 patients who presented with neck disease (i.e., Kadish D), 6 underwent both neck dissection and radiotherapy for primary management of the neck, 1 received radiotherapy alone, and 1 received neck dissection alone. The remaining three patients received palliative therapy only and all died within five months of diagnosis of metastatic disease. Two additional patients underwent neck dissection secondary to clinically suspicious nodes on imaging. Both patients were found to have pathologically negative nodes, and both developed regional recurrence, one in a lymph node basin previously dissected (level 2) and one in retropharyngeal nodes not previously dissected. Finally, two patients with DI and two patients without DI underwent elective irradiation to the neck for clinically negative nodes. No patient who received elective neck irradiation developed neck metastases.

Incidence, Laterality, and Survival Analyses by DI Status

A total of 17 of the 34 (50%) patients with DI presented with ( n = 7) or developed neck disease following primary treatment ( n = 10). In contrast, 6 of the 27 (22%) patients without DI presented with ( n = 4) or developed neck disease ( n = 2). The difference in incidence between these two groups was statistically significant ( p = 0.026). Moreover, 11 of the 34 (32%) patients with primary site DI developed bilateral neck disease. In contrast, 2 of 27 (7%) patients without DI exhibited bilateral nodal disease. This difference was statistically significant ( p = 0.018).

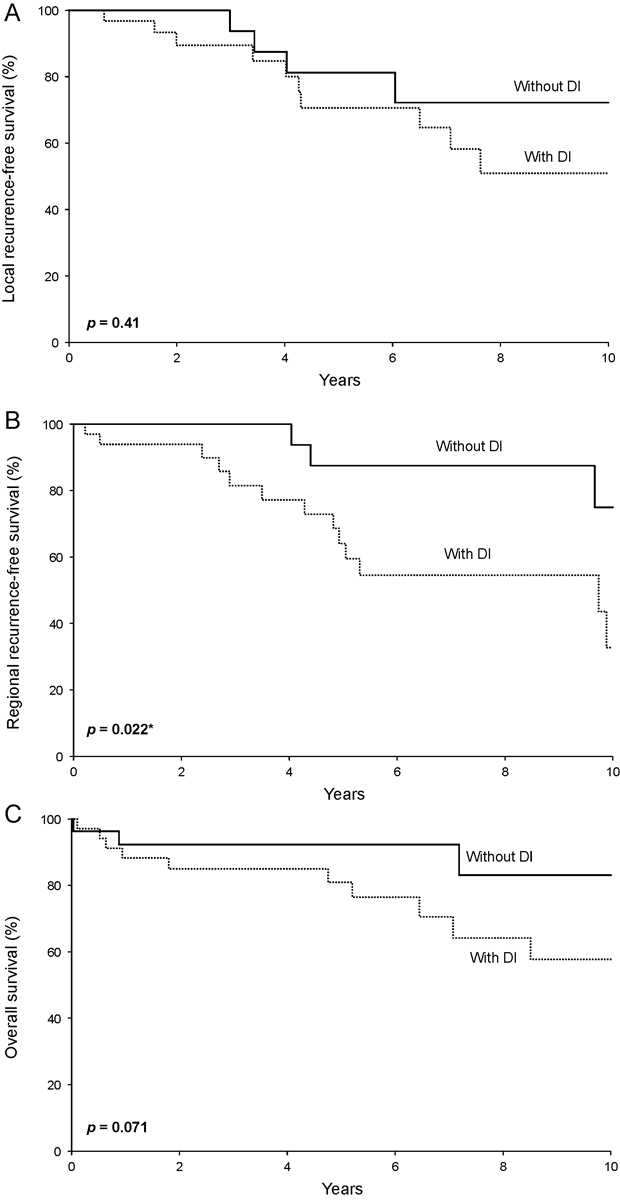

Fifteen of the 61 patients studied experienced local recurrence at a median of 4.0 years following diagnosis (IQR, 3.0–6.5). Five-year local recurrence-free survival rates (95% confidence interval [CI]; number still at risk) were 71% (54–92; 13) and 81% (64–100; 9) for patients with and without DI, respectively ( p = 0.41; Fig. 1A ).

Fig. 1.

Survival rates by dural invasion (DI) status from the date of diagnosis for ( A ) local recurrence-free survival, ( B ) regional recurrence-free survival, and ( C ) overall survival.

Sixteen patients experienced regional recurrence. Five-year regional recurrence-free survival rates (95% CI; number still at risk) were 64% (48–86; 14) and 88% (73–100; 11) for patients with and without DI, respectively ( p = 0.022; Fig. 1B ).

Patients with DI displayed worse overall survival when compared with patients without DI ( p = 0.071; Fig. 1C ). Five-year overall survival rates (95% CI; number still at risk) were 81% (68–96; 18) and 92% (83–100; 12) for patients with and without DI, respectively.

Survival Analyses by Modified Kadish Stage and DI Status

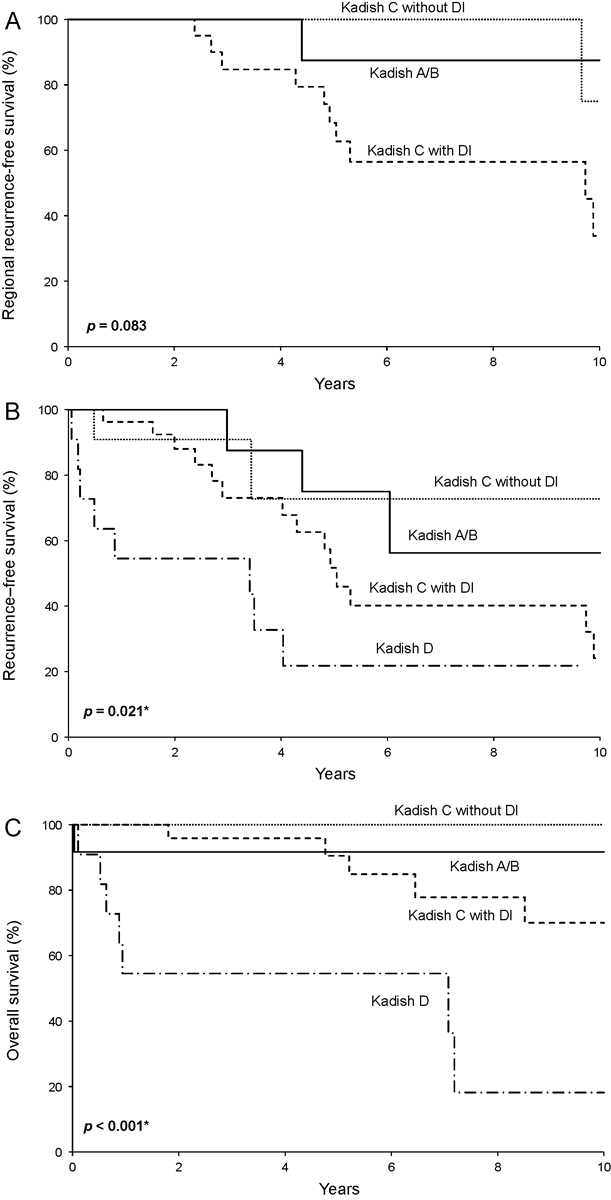

Regional recurrence-free survival for the 12 patients with Kadish A/B, the 11 with Kadish C without DI, and the 27 with Kadish C with DI is illustrated in Fig. 2A . Kadish C patients with DI were more likely to experience regional recurrence ( p = 0.083).

Fig. 2.

Survival rates by modified Kadish stage and dural invasion (DI) status from the date of diagnosis for ( A ) regional recurrence-free survival, ( B ) any disease recurrence-free survival, and ( C ) overall survival.

Twenty-eight of the 61 patients studied experienced local recurrence, regional recurrence, or distant metastases (i.e., any disease recurrence) at a median of 3.4 years following diagnosis (IQR, 1.2–4.9). Recurrence-free survival differed significantly among patients with Kadish A/B, Kadish C without DI, Kadish C with DI, and Kadish D disease ( p = 0.021; Fig. 2B ). Five-year recurrence-free survival rates (95% CI; number still at risk) were 75% (50–100; 4), 73% (45–100; 3), 52% (34–79; 9), and 22% (7–73; 2), respectively, for these four groups.

Overall survival differed significantly among patients with Kadish A/B, Kadish C without DI, Kadish C with DI, and Kadish D disease at diagnosis ( p < 0.001; Fig. 2C ), largely driven by the poor overall survival observed for Kadish D patients. Overall survival rates (95% CI; number still at risk) at 5 years following diagnosis were 92% (77–100; 5), 100% (100–100; 5), 91% (79–100; 16), and 55% (32–94; 4), respectively, for these four groups. Kadish C patients with DI displayed worse overall survival when compared with Kadish C patients without DI ( p = 0.094).

Discussion

This study examined the development of neck metastases in ENB by DI status and found that patients with DI exhibited over a twofold elevation in the incidence of neck metastases. In addition, patients with DI displayed significantly worse regional recurrence-free survival rates when compared with patients without DI. A similar association was not observed for local recurrence-free survival. Together, these findings indicate that dural involvement was uniquely associated with the development of neck disease. The laterality of neck disease also significantly differed by DI status, as bilateral neck disease was almost five times as common in patients with DI. Therefore, this research suggests that DI by ENB is linked to the development of neck metastases.

In our study, higher Hyams' grade was not significantly associated with primary neck disease or recurrent neck disease. Moreover, the difference in Hyams' grade between patients with and without DI was not statistically significant. These data therefore suggest that DI predicts neck metastases independent of Hyams' grade. In addition, only 3 of the 11 (27%) patients with positive surgical margins developed regional recurrences, and there were too few regional recurrences observed to evaluate the associations of positive surgical margin status and DI status with regional recurrence in multivariable analysis. Prior to this study, limited evidence stratified patients at increased risk for developing neck disease with ENB. One recent study found higher Hyams' grade to be associated with primary neck disease and positive surgical margins with recurrent neck disease. 10

Specific attention to DI by ENB was first considered by Dulguerov and Calcaterra in 1992. They compared the outcomes of 2 patients with DI against the outcomes of 24 patients without DI. 11 Later research from the same institution found that DI was associated with worse disease recurrence rates and overall survival. 12 Since Dulguerov and Calcaterra's initial research, several studies found utility in using their staging system when examining overall survival rates. 11 12 13 Our study also found that DI status was associated with overall survival. Further, the present study helps to elucidate why this dural distinction bears prognostic implications for patients, as this research shows that DI is associated with an increased risk of neck metastases—the most important prognosticator of long-term survival in patients with ENB. 4

Within the ENB literature, the modified Kadish staging system has been the most widely adopted. 9 However, controversy exists regarding modified Kadish C classification, as some authors feel this represents an overly broad category of patients. 12 14 This study attempted to partition modified Kadish C patients by DI status and found it was associated with worse regional recurrence-free survival, any disease recurrence, and overall survival. With further confirmatory research, this dural distinction supports the division of the broad Kadish C category into subcategories defined by the presence or absence of DI. Of note, even after separating Kadish C by DI status, Kadish D patients still exhibited a uniquely poor prognosis, which highlights the existing utility of the modified Kadish staging system.

Despite the critical implications on survival, the rate of occult neck disease in patients with a clinically node-negative neck remains unknown. This study identifies a subgroup of patients who appear to be at an elevated risk for neck metastases. As such, future research could evaluate elective neck treatment for these patients. Similarly, since previous studies examining elective neck irradiation have yet to show improved overall survival for patients, 15 16 17 18 future research could examine the outcomes of Kadish C patients with and without DI as this study suggests these two groups display differing overall survival.

In the setting of elective treatment of the neck, considerable controversy exists surrounding the most appropriate laterality. 5 Many researchers have proposed bilateral elective neck therapy, though unilateral neck treatment based on primary site laterality has also been investigated. 15 16 18 19 Despite this, recent research found that ENB primary site laterality poorly predicted neck disease laterality. 20 Contributing to the understanding of neck disease laterality with ENB, this study found that patients with DI were almost five times as likely to have bilateral cervical nodal involvement compared with patients without DI. Mechanistically, if ENB gains bilateral access to the cervical lymph nodes through dural lymphatic channels within this subgroup of patients, it follows that patients' neck metastases would likely not display a sidedness predilection. To this point, the fact that the laterality of neck disease significantly differed with DI status suggests a structural link between DI and the development of neck disease. This finding is distinct from previous speculation surrounding the midline nature of ENB and its propensity for bilateral cervical nodal involvement, as it suggests that invasion into certain structures rather than simply its midline location accounts for the frequent development of bilateral nodal disease.

This study has limitations. First, it is a retrospective analysis at a single institution with variable follow-up durations. Patients received variable primary treatment which could confound estimates of local and regional control. Specifically, patients with DI were significantly more likely to receive combination therapy comprised of surgery and adjuvant radiation with or without systemic chemotherapy. Therefore, this study found patients with DI were significantly more likely to develop neck disease despite also receiving more aggressive primary therapy. Lastly, this study is dependent on pathologic sampling of dural margins which may be incomplete and could confound the analysis.

Conclusion

These data suggest that patients with DI by ENB are at an increased risk for the development of cervical metastases to bilateral nodal basins and poorer survival outcomes. Future research to determine whether elective nodal management with surgery and/or radiation will impact overall prognosis in patients presenting with DI will be of critical importance. Finally, this study supports the division of the broad Kadish C category into subcategories defined by the presence or absence of DI, as those with DI exhibited worse regional recurrence rates, any recurrence-free survival, and overall survival.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors report no conflict of interest in submitting this article for publication. No funding was received to conduct this research.

The currently submitted manuscript represents original research that has not been previously submitted. We performed this research with approval from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB 15–002683).

References

- 1.Dulguerov P, Allal A S, Calcaterra T C. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a meta-analysis and review. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(11):683–690. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broich G, Pagliari A, Ottaviani F.Esthesioneuroblastoma: a general review of the cases published since the discovery of the tumour in 1924 Anticancer Res 199717(4A):2683–2706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Bonnecaze G, Lepage B, Rimmer J et al. Long-term carcinologic results of advanced esthesioneuroblastoma: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(01):21–26. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3320-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jethanamest D, Morris L G, Sikora A G, Kutler D I. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a population-based analysis of survival and prognostic factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(03):276–280. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naples J G, Spiro J, Tessema B, Kuwada C, Kuo C L, Brown S M. Neck recurrence and mortality in esthesioneuroblastoma: Implications for management of the N0 neck. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(06):1373–1379. doi: 10.1002/lary.25803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes T Jet al. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels Nature 2015523(7560):337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aspelund A, Antila S, Proulx S T et al. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med. 2015;212(07):991–999. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyams V J, Batsakis J G, Michaels Let al. 1988:343. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita A, Ebersold M J, Olsen K D, Foote R L, Lewis J E, Quast L M.Esthesioneuroblastoma: prognosis and management Neurosurgery 19933205706–714., discussion 714–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nalavenkata S B, Sacks R, Adappa N D et al. Olfactory neuroblastoma: fate of the neck--a long-term multicenter retrospective study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154(02):383–389. doi: 10.1177/0194599815620173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dulguerov P, Calcaterra T. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the UCLA experience 1970-1990. Laryngoscope. 1992;102(08):843–849. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tajudeen B A, Arshi A, Suh J D et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: an update on the UCLA experience, 2002-2013. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2015;76(01):43–49. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malouf G G, Casiraghi O, Deutsch E, Guigay J, Temam S, Bourhis J. Low- and high-grade esthesioneuroblastomas display a distinct natural history and outcome. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(06):1324–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Gompel J J, Giannini C, Olsen K D et al. Long-term outcome of esthesioneuroblastoma: hyams grade predicts patient survival. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2012;73(05):331–336. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demiroz C, Gutfeld O, Aboziada M, Brown D, Marentette L J, Eisbruch A.Esthesioneuroblastoma: is there a need for elective neck treatment? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 20118104e255–e261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang W, Mohamed A S, Fuller C D et al. The role of elective nodal irradiation for esthesioneuroblastoma patients with clinically negative neck. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2016;6(04):241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monroe A T, Hinerman R W, Amdur R J, Morris C G, Mendenhall W M. Radiation therapy for esthesioneuroblastoma: rationale for elective neck irradiation. Head Neck. 2003;25(07):529–534. doi: 10.1002/hed.10247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin Z Z, Luo J W, Gao L et al. Spread patterns of lymph nodes and the value of elective neck irradiation for esthesioneuroblastoma. Radiother Oncol. 2015;117(02):328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banuchi V E, Dooley L, Lee N Y et al. Patterns of regional and distant metastasis in esthesioneuroblastoma. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(07):1556–1561. doi: 10.1002/lary.25862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marinelli J P, Van Gompel J J, Link M Jet al. Volumetric analysis of olfactory neuroblastoma skull base laterality and implications on neck diseaseLaryngoscope 2017 [DOI] [PubMed]