Abstract

Background/Aims:

Sparse literature exists on the challenges and ethical considerations of including people with limited access to healthcare such as the uninsured and low-income in clinical research in high-income countries. However, many ethical issues should be considered with respect to working with uninsured and low-income participants in clinical research, including enrollment and retention, ancillary care, and post-trial responsibilities. Attention to the uninsured and low-income is particularly salient in the U.S. due to the high rates of uninsurance and underinsurance. Thus, we conducted a scoping review on the ethical considerations of biomedical clinical research with uninsured and low-income participants in high-income countries in order to describe what is known and to pinpoint areas of needed research on this issue.

Methods:

MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, and Scopus databases were searched using terms that described main concepts of interest (e.g. uninsured, underinsured, access to healthcare, poverty, ethics, compensation, clinical research). Articles were included if they met four inclusion criteria: (1) English; (2) high-income countries context; (3) about research participants who are uninsured or low-income, which limits their access to healthcare, and in biomedical clinical research that either had a prospect of direct medical benefit or were offered to them on the basis of their ill health; (4) recognizes and/or addresses challenges or ethical considerations of uninsured or low-income participants in biomedical clinical research.

Results:

The searches generated a total of 974 results. Ultimately, 23 papers were included in the scoping review. Of 23 articles, the majority (n=19) discussed enrollment and retention of uninsured or low-income participants. Several barriers to enrolling uninsured and low-income groups were identified, including limited access to primary or preventative care; lack of access to institutions conducting trials or physicians with enough time or knowledge about trials; overall lack of trust in the government, research, or medical system; and logistical issues. Considerably fewer articles discussed treatment of these participants during the course of research (n=5) or post-trial responsibilities owed to them (n=4). Thus, we propose a research agenda that builds upon the existing literature by addressing three broad questions: (1) What is the current status of uninsured research participants in biomedical clinical research in high-income countries? (2) How should uninsured research participants be treated during and after clinical research? (3) How, if at all, should additional protections for uninsured research participants affect their enrollment?

Conclusions:

This review reveals significant gaps in both data and thoughtful analysis on how to ethically involve uninsured research participants. To address these gaps, we propose a research agenda to gather needed data and theoretical analysis that addresses three broad research questions.

Keywords: Ethic, clinical research, insurance, income, socioeconomic status, enrollment, post-trial, ancillary care

Introduction

Participation in clinical research can offer individuals with limited access to healthcare an opportunity to receive interventions for conditions that otherwise go untreated; however, these interventions are unproven. Discussions about the ethics of research with participants who lack access to healthcare center almost exclusively on trials in low and middle income countries (LMIC).1–3 Moreover, existing literature that addresses people who are uninsured or otherwise lack healthcare access in high-income countries (HIC) focuses on community-based and non- therapeutic trials (i.e. educational interventions, natural history studies, survey/questionnaires, etc.).4–13

However, research participants in HIC who are uninsured or otherwise lack access to healthcare encounter limitations similar to those faced by participants in LMIC. Thus, their inclusion in research raises often overlooked but parallel ethical considerations.

Attention to including the uninsured in clinical research is particularly salient in the U.S. A significant proportion of the U.S. population (an estimated 8.8% or 28.2 million in 2016) lacks any insurance coverage,14,15 many more are underinsured,16 and for the first time since the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, the uninsurance rate for adults in the U.S. is on the rise.17 Moreover, a growing amount of data suggests that the uninsured encounter significant barriers in accessing healthcare, perceive discrimination when receiving treatment, and experience poorer health outcomes for both acute and chronic conditions.18–26

We conducted a scoping review on the ethical considerations of biomedical clinical research with uninsured and low-income participants in HIC in order to describe what is known and to pinpoint areas of needed research on this issue. Our review revealed that little attention has been paid to ethical issues regarding research participation of uninsured and low-income participants in HIC. Analyses that do address disadvantaged research participants often mention that minority groups are more likely to be uninsured and have low-income, but do not distinguish the effects of socioeconomic status from those of race, ethnicity, linguistic and cultural barriers, historical context, etc.27–30

Even when studies explore the challenges and ethical considerations of working with the uninsured, most only discuss issues regarding enrollment and retention, leaving other ethically challenging issues like ancillary and post-trial care relatively neglected. Building on these results, we propose a research agenda to gather needed data and theoretical analysis, as well as raise attention to uninsured participants in biomedical clinical research.

Methods

Search strategy

A combination of controlled vocabulary terms (i.e., Medical Subject Headings, Emtree) and keywords were searched in the MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, and Scopus databases on February 2018. Used terms described the main concepts of interest: uninsured, underinsured, access to healthcare, poverty, ethics, compensation, and clinical research (See Appendix A in the online supplementary material for MEDLINE search strategies). The references of eligible papers were also reviewed to identify additional relevant articles.

Selection criteria

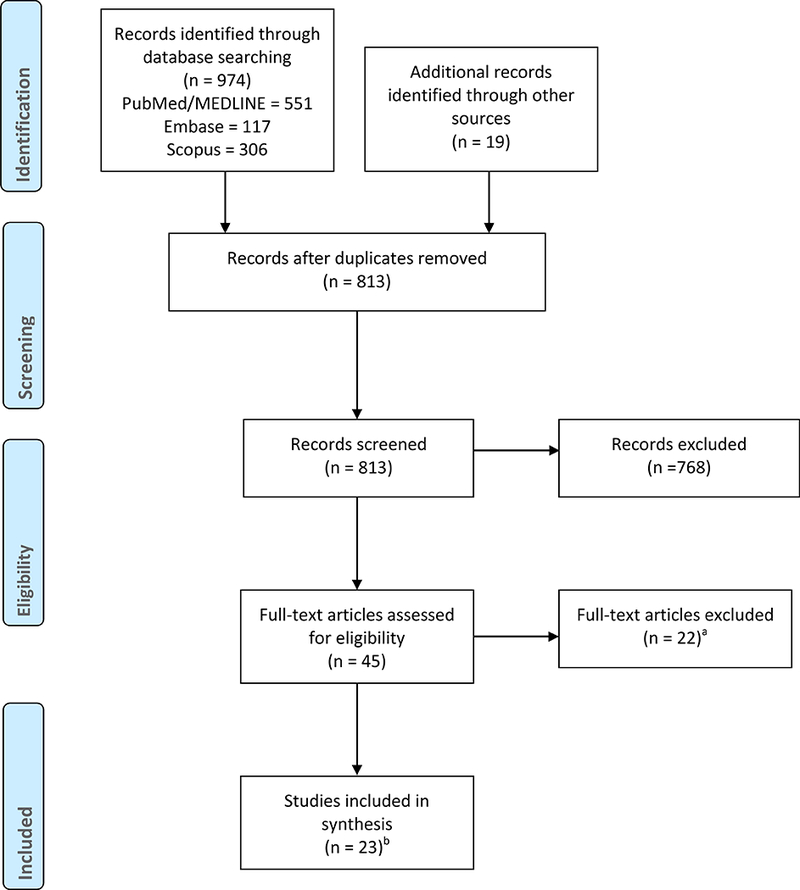

We followed PRISMA guidelines for our scoping review (Figure 1). One author (HC) screened the titles and abstracts of results to assess their relevance to the research question. A second author (CG) verified eligibility of the references, including when eligibility was unclear. Articles passed the title/abstract screening if they did not meet any of the exclusion criteria and clearly met at least three of the inclusion criteria. When the eligibility of an article was unclear on only one inclusion criteria, we included the article in the second screening. Two authors (HC and CG) then reviewed the full-text of articles that passed the first screening to confirm that all inclusion criteria were met.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included studies.

aExcluded articles included studies not about high-income countries (n=2), studies that did not acknowledge challenges or ethical considerations (n=5), studies that focused on minority populations without considering the impact of uninsurance or low income (n=6), and studies not about participants in biomedical trials that either had a prospect of direct medical benefit or was offered to them on the basis of their ill health (n=9). Some of the excluded articles fit into more than one of these categories. Those articles were categorized by their primary reason for exclusion.

bThree primary articles were part of the systematic reviews included, and the Ford et al. 2008 systematic review was included in the Boneveski et al. 2014 systematic review. We included these articles because we wanted to capture the amount of attention paid to the challenges and ethical considerations of working with the uninsured and low-income in research, and because the primary papers and the systematic reviews framed themselves in unique ways.

One author (HC) applied the same selection criteria for both the title/abstract and full-text screening for articles in the references of eligible papers from the original MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, and Scopus databases.

All included articles met four inclusion criteria: (1) English; (2) HIC context (determined by World Bank high-income economies, including the U.S., Canada, Australia, and certain countries in Europe and Asia); (3) about research participants who are uninsured or low-income, which limits their access to healthcare, and in biomedical clinical research that either had the prospect of direct medical benefit or was offered to them on the basis of their ill health; (4) recognizes and/or addresses challenges and/or ethical considerations of uninsured or low-income participants in biomedical clinical research.

We excluded articles if they met any of three exclusion criteria: (1) letters, books, and book reviews; (2) studies about or involving research participants who are in marginalized or minority groups that are more likely to be uninsured or low-income, but focus on challenges and barriers due to characteristics such as minority status and not insurance or income; (3) studies about or involving research participants in non-biomedical or healthy volunteer trials without prospect of benefit. Although the uninsured are often discussed in the context of non-biomedical or healthy volunteer trials, we excluded these trials because the ethically salient issues for participants receiving medical care or benefit differ from issues raised by trials in which participants cannot reasonably expect such care or are not seeking medical benefit. For example, bioethicists worry about payment and possible undue inducement of healthy volunteer research participants, who are usually motivated by money.31,32 Payment may be less of a factor for participants who join research in order to access healthcare, and other factors (e.g. desire for healthcare, provision of ancillary care or post-trial care) may be more likely to affect ethical analyses on how to recruit, enroll, and treat this particular group of uninsured participants. Moreover, the moral imperative to include uninsured participants who are ill in therapeutic trials - or to not unjustly exclude for their “protection” - differs from that of participants in non-therapeutic or non-biomedical trials.

Data extraction

One author (HC) independently extracted data from the studies that met our inclusion criteria into standardized tables (Tables 2, 3, 4). All authors reviewed and agreed upon the analysis of the data.

Table 2.

Papers that discuss enrollment and retention of uninsured research participants.

| Empirical | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/year | Country | Study design | Ethical theme(s) discussed |

Main findings |

| Bonevski et al. 201433 | U.S., Canada Europe, Australia |

Systematic review on socially disadvantaged groups | Enrollment, retention |

Research should include socially disadvantaged populations and address the significant barriers to enrolling and retaining these groups. |

| Farmer et al. 200738 | U.S. | Focus groups with African American and low-income white women | Enrollment | Mistrust of research, lack of community structure, and logistical factors pose barriers of enrolling low socioeconomic status minorities and women. |

| Ford et al. 200834 |

Developed countries (broad) |

Systematic review on underrepresented populations in cancer trials | Enrollment | Lack of health insurance and low socioeconomic status is associated with reduced enrollment in cancer clinical trials. This problem must be addressed both on the level of individual studies and policy. |

| Gross et al. 200539 | U.S. | Case control study of older women with breast cancer | Enrollment | Low socioeconomic status, independent of race, was associated with lower trial enrollment in older women with breast cancer. This may be due to bad access to centers conducting trials, later-stage cancers, co- morbid conditions, logistical barriers, or biological impacts of poverty. |

| Grady et al. 200640 | U.S. | Focus group with urban community representatives | Enrollment | Mistrust and logistical issues, including post-trial worries, pose barriers of enrolling low socioeconomic status communities in research. |

| Humphreys & Weisner 200041 | U.S. | Retrospective study on alcohol treatment patients | Enrollment | Exclusion criteria in alcohol trials disproportionately exclude low socioeconomic status patients. |

| Mitchell & Kline 200842 |

U.S. | Case control study of emergency department patients being offered a minimal-risk study | Enrollment | Uninsured patients were less likely to participate in a minimal-risk study in the emergency department. Studies should pay attention to informed consent biases. |

| Nyamathi et al. 200443 | U.S. | Focus group with homeless minority groups | Enrollment | Homeless minority groups are interested in participating in vaccine trials. Mistrust of government and research as well as lack of education pose barriers to participation. |

| Slomka et al. 200744 | U.S. | Interview study with low- income, African-American drug users | Enrollment | Impoverished drug users will participate in research only if financially compensated. They are not worried about risk of exploitation or undue inducement as long as compensation is proportional to risks and inconvenience. |

| Shavers- Hornaday et al. 199735 | U.S. | Literature review on possible reasons for low research participation of African Americans | Enrollment | Uninsurance and lack of access to healthcare can disproportionally exclude minorities from trials due to limited relationship with doctors who are knowledgeable about trials and increased likelihood of late-stage or co-morbid conditions that meet exclusion criteria. |

| Webb et al. 201045 | U.S. | Interventional study on minority, low-income women | Enrollment, retention |

Minority women who have no insurance or low- income were more willing to participate in a prevention study that offered treatment. This suggests the difficulty enrolling and recruiting of uninsured or low-income may be due to study design. |

| Conceptual | ||||

| Author/year | Country | Ethical theme(s) discussed | Main takeaway | |

| El-Sadr & Capps 199246 |

U.S. | Enrollment, informed consent | AIDS clinical trials have disproportionally low enrollment of low socioeconomic status, minority participants due to lack of access to institutions conducting trials, disillusionment with the medical system, lack of relationships with primary care physicians, and logistical barriers. Social workers should provide support. | |

| Guerrero & Heller 200347 | U.S. | Exploitation, undue inducement, informed consent | Low socioeconomic status raises concerns of exploitation and undue inducement. The informed consent process currently is insufficient. | |

| Kolata & Eichenwald 199936 |

U.S. | Enrollment, exploitation, undue inducement, informed consent | Uninsured participants use clinical research as a form of healthcare. This poses ethical problems for either enrollment or exclusion of uninsured participants. The lack of post-trial care also poses a problem for uninsured research participants. | |

| Merill 199948 | U.S. | Enrollment | Cancer research should be enrolling uninsured and underinsured participants who currently face barriers to participation. Insurance coverage should be provided for all National Cancer Institute sponsored, peer-reviewed cancer trials. | |

| Pace et al. 200349 |

U.S. | Enrollment, exploitation, undue inducement, informed consent | Uninsured participants should be enrolled in clinical research. Exploitation and undue inducement do not pose enough of a problem to merit exclusion. | |

| Stone 200350 | U.S. | Enrollment, exploitation, undue inducement, informed consent | Informed consent as it stands does not fully protect economically or educationally disadvantaged research participants from exploitation and undue inducement. IRBs may need to limit the types of trials allowed to minimal risk or research with direct benefits. | |

| Vasgird et al. 200051 | U.S. | Enrollment, informed consent | Informed consent as it stands does not fully protect uninsured research participants. Uninsured participants may not have other options than research for healthcare. | |

| Welsh et al. 199452 | U.S. | Enrollment | Lack of insurance poses barriers to enrollment of minorities because of lack of relationship with primary care providers, lack of trust in medicine, and lack of access to evaluation, diagnoses, and trial referral. Financial incentives, ancillary care, and transportation may help enroll minorities. | |

Table 3.

Papers that discuss treatment of uninsured participants during course of research

| Empirical | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/year | Country | Study design | Ethical theme(s) discussed |

Main findings |

| Jacobson et al. 20162 | U.S. | Interviews with low- income people | Ancillary Care |

Low-income people expect ancillary care if they participate in clinical research. This may call into concern their informed consent. |

| Grady et al. 200640 | U.S. | Focus group with urban community representatives | Ancillary Care |

Community engagement, fair payment, and provision of care may encourage participation. |

| Koblin et al. 199853 | U.S. | Survey study of populations with highrisk of HIV | Ancillary Care |

Those without insurance in high-risk populations of HIV infection were more willing to enroll in vaccine trials. However, these groups may expect free ancillary care during the trial, so decisions about ancillary care have to be addressed. |

| Conceptual | ||||

| Author/year | Country | Ethical theme(s) discussed | Main takeaway | |

| Dal-Ré et al. 20161 | U.S., EU, Canada | Ancillary care | In order to provide a favorable risk-benefit ratio and prevent exploitation, researchers may provide ancillary care and other benefits to participants who lack access to healthcare. | |

| Vasgird et al. 200051 | U.S. | Compensation for research related harms | Without compensation for research-related harms, uninsured participants remain unethically vulnerable during the course of research participation. | |

Table 4.

Papers that mention post-trial care and access for uninsured research participants.

| Empirical | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/year | Country | Study design | Ethical theme(s) discussed |

Main findings |

| Grady et al. 200640 | U.S. | Focus group with urban community representatives |

Post-trial access, post-trial care | Uninsured people from low socioeconomic status communities worry about post-trial care and access, which may pose a barrier to their enrollment. |

| Conceptual | ||||

| Author/year | Country | Ethical theme(s) discussed | Main takeaway | |

| Clemmitt 199137 | U.S. | Post-trial care | Low-income participants must receive ongoing medical care after a trial concludes in order for their enrollment to be ethical. | |

| Dal-Ré et al. 20161 | U.S., EU, Canada | Post-trial access | In order to provide a favorable risk-benefit ratio and prevent exploitation, researchers may provide post-trial access to participants who lack access to healthcare. | |

| Kolata & Eichenwald 199936 |

U.S. | Post-trial care | Uninsured research participants often do not receive post-trial care unless they can find another trial and feel abandoned. | |

Included articles fell into two broad categories: 1) conceptual papers that discuss ethical treatment of uninsured or low-income participants at various stages of biomedical clinical research in HIC, or 2) empirical papers on the perspectives of the uninsured or low-income on clinical trials or on the barriers of enrolling and/or retaining uninsured or low-income participants. We further categorized the conceptual and empirical articles by the stage of research they discussed: enrollment and retention (Table 2), treatment during the course of research (Table 3), or post-trial responsibilities (Table 4).

We further extracted themes from each of the articles included in our review. Themes regarding “enrollment and retention” included barriers for enrollment and retention, informed consent, financial incentives, exploitation, and undue inducement among others. Although retention refers to treatment during the course of research, we grouped it with enrollment because the papers that addressed one often addressed the other. Themes regarding “treatment during the course of research” included considerations such as ancillary care and compensation for research-related harms for purposes other than retention. Themes regarding “post-trial responsibilities” included post-trial care and access.

Results

The searches generated a total of 974 results from PubMed/MEDLINE (551), Embase (117), and Scopus (366). After removing duplicates, 797 unique publications remained. Of the 797 results, 27 passed an initial title/abstract screening and were read in full. Twelve articles were excluded because they either met one of the three exclusion criteria or because they did not meet the all four inclusion criteria, leaving 15 eligible articles (Figure 1).

Nineteen articles were extracted from the references of the 15 articles via a title/abstract screening. Eight of the 19 ultimately passed the full-text screening and were included in our review for a total of 23 articles (Figure 1).

Characteristics of reviewed articles

Of the 23 results, there were 13 empirical articles and 10 conceptual articles. Ten of the 13 empirical articles involved uninsured or low-income participants, and the remaining three empirical articles were literature reviews of barriers to enrollment and/or retention in clinical research of disadvantaged or underrepresented groups (including uninsured and low-income)33−35 (Table 1). The reviews did not focus solely on the uninsured or low-income, and/or looked at a different subset of clinical trials.

Table 1.

Scoping review article type by frequency.

Eight of the 10 conceptual articles reviewed challenges or ethical considerations of involving uninsured or low-income research participants in biomedical clinical research. Two were newspaper or magazine articles, published in The New York Times 36 and The Scientist 37 respectively (Table 1). The majority (n=19) of the articles in our review discussed enrollment and retention of uninsured or low-income participants.33–36,38–52 Considerably fewer articles discussed treatment of these participants during the course of research (n=5)1,2,40,51,53 or post-trial responsibilities owed to uninsured or low-income participants (n=4) 1,36,37,40 (Table 3). Three papers 1,36,40 discussed more than one of these issues.

Enrollment and retention

Most of the papers (19/23) in our review described challenges and ethical considerations of enrollment and retention. Eleven 33–35,38–45 of the 19 papers were empirical studies, and eight 36,46−52 were conceptual studies (Table 2).

The empirical papers on enrollment and retention identified several barriers to enrolling uninsured and low-income groups, both independent of and associated with other demographic factors (Table 2). Eight papers 33–35,38,39,41,43,45 explicitly mentioned that uninsured or low-income participants should be enrolled. Of the eight, six 33,35,38,39,41,45 gave reasons of scientific validity, five 33,34,38,39,43 gave reasons of benefiting or addressing disparate health outcomes for groups with greatest burden of disease, and two 33,34 gave reasons of fair access to trial benefits. Barriers to enrollment included limited access to primary or preventative care due to uninsurance or low-income, which lead to later diagnoses and development of co-morbid conditions that met exclusion criteria, lack of access to institutions conducting trials or to physicians with enough time or knowledge about trials, and overall lack of trust in the government, research, or medical system. 33–35,38,39,41,45 Logistical issues such as lack of time, transportation, or daycare services for children constituted barriers for both enrollment and retention of uninsured or low-income participants in clinical research.33,34,38,39,44,45 One paper 42 cited informed consent bias as a potential barrier

Two papers, Grady et al.40 and Slomka et al.44 discussed ways to promote uninsured or low-income participation in clinical research. Grady et al.40 focused on respect for participants, while Slomka et al.42 focused on financial incentives.

Interestingly, the focus group and patient interview studies 38,40,43,44 found that uninsured or low-income communities were willing to participate in biomedical clinical research despite logistical, structural, and personal barriers to enrollment. Given the difficulty of enrolling and retaining low-income groups despite willingness to participate, Webb et al.45 and Humphreys and Weisner 41 suggest study design (i.e. exclusion criteria) may be disproportionally excluding uninsured, low-income, or minority patients.

To address barriers to both enrollment and retention, seven studies propose strategies such as financial assistance for transportation or time spent in research (n=4), 33,35,39,45 collaboration with the community or community leaders to improve trust (n=7),33,35,37,39,40,44,45 reminder calls (n=2),33,45 financial incentives (n=5),33,35,43–45 and monitoring of medical welfare throughout the trial (n=2).33,40

The eight conceptual papers on enrollment and retention discussed concerns about whether or not to enroll (n=6), 36,46,48–50,52 informed consent (n=6), 36,46,47,49,50,51 exploitation and undue inducement (n=4). 36,46,47,49 Stone 50 raised concerns about informed consent and explicitly recommended limiting the type of trials open to uninsured and low-income participants to minimal risk research or research with direct benefits. Kolata and Eichenwald 36 remained ambivalent about whether or not uninsured participants should be enrolled or excluded. El-Sadr and Capps,46 Merrill,48 and Pace et al.49 explicitly argued for the inclusion of uninsured and low-income participants in cancer, AIDS, and general clinical trials respectively. Welsh et al.52 argued for inclusion of minority groups that are more likely to face economic barriers. Guerrero and Heller 47 and Vasgird et al.51 raised issues about informed consent due to power dynamics between patients and physicians, exploitation, undue inducement, and lack of compensation for research related harms.

Treatment during the course of research

Five of 23 papers mentioned ethical considerations regarding the treatment of uninsured and low-income participants during the course of research, specifically ancillary care (n=4)1,2,40,53 and compensation for research-related harms (n=1)51 (Table 3). Three 2,40,53 of five were empirical, and two 1,51 were conceptual.

The three empirical papers stated or hypothesized that uninsured or low-income people expected ancillary care during research participation. Jacobson et al.2 found that low-income participants would not participate in research without ancillary care provision, and Grady et al.40 reported that representatives from low-income, urban communities in the U.S. saw ancillary care throughout the course of research as necessary to respect participants.

None of the empirical papers proposed when or how much ancillary care to provide. In fact, Jacobson et al.2 raised a concern that providing ancillary care could exacerbate participants’ misunderstanding of the purpose of research as treatment or potentially be a form of coercion of low-income participants. Koblin et al.53 suggested that unrealistic expectations of ancillary care may be a problem for uninsured participants that must be adequately addressed before enrolling them. However, one conceptual paper, Dal-Ré et al.,1 proposed ancillary care as a method to ensure a fair level of benefits to participants who lack access to healthcare.

The other conceptual paper about treatment of uninsured and low-income participants during the course of research, Vasgird et al.,51 focused on compensation for research-related harms, arguing that without compensation for research-related harms, uninsured participants remain vulnerable during the course of research participation.

Post-trial care and access

Four papers mention post-trial access (n=3)1,36,40 or post-trial care (n=2)37,40 for uninsured or low-income research participants (Table 4). Three of the four papers were conceptual, two of which were newspaper or magazine articles.

Clemmitt 37 suggested that research community members believed that ongoing medical care post-trial was required to ethically enroll low-income participants. Grady et al.40 described how representatives of low-income communities raised concerns about post-trial access to medications and healthcare in general for uninsured research participants. These representatives stated that trials should have post-trial plans to adequately provide care to uninsured participants, even if that means the research team has to continue to provide that care.

Kolata and Eichewald 36 raised concerns about lack of post-trial access for uninsured research participants due to potential health consequences of terminating treatment, while Dal-Ré et al.1 proposed post-trial access to experimental medications as another strategy to provide a fair level of benefits to participants who are uninsured or otherwise lack access to healthcare.

Discussion

Limitations

The review has several limitations. First, the “uninsured” consists of a diverse group of people who lack access to healthcare to various extents and for various reasons, have different needs, and require different ethical considerations in clinical research. Second, many studies in our review focus on minority or marginalized groups (e.g. African Americans, Latino women, homeless, drug addicts) who are more likely to be uninsured or broadly study low-income, socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. Thus, many of the ethical considerations discussed apply not just to uninsured participants but also underinsured or other marginalized participants. Third, some existing studies that do discuss exploitation, ancillary care, and post-trial access were excluded because they focus on LMIC or on paying healthy volunteers, and do not recognize the particular circumstances of the uninsured seeking healthcare through research in HIC.3,31,32,54 Fourth, the majority (20/23)2,35–53 of our studies address U.S. participants only, leaving out other HIC some of which have different healthcare systems. Finally, our review focuses on biomedical clinical research, and not on the ethical treatment of uninsured research participants in trials such as non-vaccine healthy volunteer studies, non-treatment community-based research such as survey studies, public health research, or natural history studies. These types of research raise different ethical issues that should be analyzed separately, and may be areas for future research.

Implications & future research

This scoping review reveals the lack of attention to the ethics of clinical research in HIC with uninsured and low-income people who are seeking healthcare. The articles in this review, although limited in number, seem to agree that uninsured persons should be included in research, and that special consideration might be needed in informed consent, financial compensation, ancillary care, compensation for research-related injury, and post-trial responsibilities. However, there are significant gaps in both data and thoughtful analysis on how to ethically involve uninsured research participants in biomedical clinical research offered to them on the basis of their ill health or with a prospect of direct medical benefit.

Building on the literature and gaps identified by this systematic review, we propose future research to begin to address three broad questions (Table 5).

Table 5.

Proposed research agenda for biomedical research with uninsured research participants in high-income countries.

| What is the current status of the uninsured research participant in biomedical clinical research? |

|---|

| 1. How often are uninsured participants included in biomedical research? 2. Are there certain types of studies more likely to include or exclude uninsured research participants, for example by condition or phase? 3. Are uninsured research participants treated any differently with respect to ancillary care, treatment of adverse events, or post-trial transitions? 4. Are there differences in enrollment or treatment of uninsured participants based on the funding source of a trial? 5. How often do research institutions or investigators take healthcare access into account when deciding about enrollment, ancillary care, or post trial care? 6. How well are research participants informed about the costs to them of participation? 7. How does insurance and socioeconomic status affect research participants independently of other demographic factors such as race or gender? |

| How should uninsured research participants be treated during and after clinical research? |

| 1. Is the treatment of uninsured participants in high-income countries different or similar to treatment of participants in low and middle income countries who lack access to health care? 2. Should uninsured research participants in high-income country research receive differential ancillary care, coverage for medical costs, or compensation for research related injury? 3. Do researchers have special responsibilities in transitioning uninsured research participants at the end of a trial? Or in providing post-trial access? 4. How should guidance or institutional policies address the challenges and ethical considerations of including uninsured or low-income participants? |

| How, if at all, should additional protections for uninsured research participants affect their enrollment? |

| 1. Should issues of post-trial and ancillary care affect enrollment of participants who lack access to healthcare and require more resources? If so, how? 2. How should fair participant selection and concerns about scientific validity be balanced with concerns about undue inducement for participants who cannot access needed healthcare services outside of research? 3. Should recent changes in uninsurance rates or in clinical research influence how we think about enrollment of uninsured research participants? 4. How should risks of exploitation be minimized or avoided? |

(1). What is the current status of the uninsured research participant in biomedical clinical research?

The articles in this review do not make clear how often uninsured participants are enrolled in treatment or vaccine trials or how they are treated during research participation. Inconsistencies exist between included articles, with some suggesting low rates of research participation of the low-income and uninsured and others suggesting an increasing rate of participation, and several noting that no clear picture exists. However, it is not unreasonable to think that the uninsured face barriers in accessing clinical trials. Some authors from the 1990s cancer literature noted that even patients with insurance were prevented from enrolling in cancer clinical trials because of costs and insurance reimbursement policies.55

Future research should try to elucidate the enrollment rate of uninsured and low-income participants in treatment or vaccine trials, and whether there are particular types of trials uninsured participants are more likely to be enrolled in or excluded from. The latter is especially important since data suggest that certain minority groups are more likely to be enrolled in phase I healthy volunteer trials than in later phase treatment trials.56 Similarly, given the increasing private sponsorship of clinical trials in the U.S.57 looking at uninsured participants in publicly funded versus privately funded trials could address interesting ethical questions such as 1) Are uninsured participants more likely to enroll in trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies or by public sponsors? 2) Are they treated differently (e.g. insurance coverage, ancillary care or post-trial care provision) in these trials? And, 3) Are there ethical differences in what uninsured participants are owed based on the funding source of a trial?

There are also no available data about what happens when those who are uninsured are injured in research or suffer an adverse event, nor the extent to which researchers pay attention to issues of uninsurance and income in transitioning participants to needed healthcare at the end of a study.

Moreover, we do not know whether or to what extent research institutions and investigators take healthcare access into account when deciding about enrollment, ancillary care, or post trial care. Similarly, do certain institutional policies or protocols exclude participants based on health insurance status? Do any provide medical care or coverage of medical costs (and which ones) for their research participants? Do the composition and attitudes of the institution’s staff affect enrollment of uninsured patients in clinical trials?58

Given the possibility that socioeconomic status could independently affect willingness and ability to participate in trials,36 future research should also look at the effects of insurance and income on research participation independently of other demographic factors such as race or gender or the interaction of these factors.58

Gathering data about the current status of the uninsured in research may also begin to answer other research questions about how uninsured participants are and should be treated during and after research.

(2). How should uninsured research participants be treated during and after clinical research?

The broader literature on relevant ethical issues like ancillary care and post-trial access does not focus on the uninsured or on HIC.3,54 Little has been written about similarities or differences between research participants or lack of healthcare access in LMIC and HIC. These comparisons could inform how we treat or should treat research participants who lack access to healthcare in HIC. For example, Jacobsen et al.2 proposed collecting data on ancillary care practices in HIC using the descriptive methodologies used in LMIC and comparing the findings.

Moreover, attention to post-trial responsibilities, a relatively recent idea introduced by the Declaration of Helsinki (2000), is still sparse in any context. Conceptual papers could address any particular considerations in determining post-trial responsibilities to research participants who are uninsured or otherwise lack access to healthcare access in HIC.

A better understanding of the ethics of enrolling uninsured participants and how they should be treated during and after biomedical clinical research may also help to influence guidance and policies on compensation for research-related harms, ancillary care, and post-trial care.

(3). How, if at all, should additional protections for uninsured research participants affect their enrollment?

Many existing ethical discussions about the uninsured and low-income in research took place in late 1990s and early 2000s, as evidenced by the dates of the papers in our review. However, both healthcare and clinical research have changed significantly in the last decade. Uninsurance rates in the U.S., which reached their peak in 2013 prior to Medicaid expansion and other Affordable Care Act changes, have started to rise again.14,17 One challenge is balancing fair participant selection and concerns about scientific validity with concerns about undue inducement when offering participants access to healthcare services that they otherwise cannot access. How should possible exploitation be considered when determining who to enroll in a study? Should financial compensation or ancillary care for uninsured or low-income participants be different from other enrollees, how would such differences be justified, and how can we prevent both exploitation and undue inducement? Addressing these questions would expand the existing literature on undue inducement and exploitation, which preferentially focuses on payment rather than other benefits, or on healthy volunteers rather than low-income participants primarily seeking healthcare access.31,32,59–61

Findings from our scoping review have potential implications beyond setting a research agenda. Research teams conducting biomedical clinical research in HIC should pay more attention to the existence (or lack thereof) of uninsured or low-income participants in their trials. The themes identified and discussed by the reviewed articles may help teams assess their treatment of participants who are uninsured or otherwise lack access to healthcare and make changes to ensure that their studies remain ethical. Paying more attention on both a broad and individual level to the plight of the uninsured and underinsured may help improve the treatment of vulnerable and forgotten participants caught in the throes of a healthcare crisis.

Conclusion

Overall, our review reveals a lack of attention to uninsured and low-income individuals in the research context, and even less attention on the salient ethical issues of including uninsured and low-income participants in biomedical clinical research. Despite this, there are many important ethical questions and challenges that should be addressed especially in the current climate of healthcare access in the U.S. We hope that by elucidating the dearth of empirical and theoretical research, we will prompt additional studies guided by our proposed research agenda that may lead to future practices and protections regarding uninsured and low-income research participants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alicia A. Livinski, NIH Library, for literatures searching and manuscript preparation assistance.

Appendix A: MEDLINE/PubMed search strategies, searching studies published in English:

Underinsured + clinical study + ethics/compensation

(uninsured OR underinsured) AND (“clinical trial”[tw] OR “clinical trials”[tw] OR “clinical study”[tiab] OR “clinical studies”[tiab] OR “clinical research”[tiab] OR “Clinical Studies as Topic”[Mesh] OR subject[tiab] OR subjects[tiab] OR participant*[tiab] OR volunteer*[tiab] OR “patient participation”[tiab] OR “research subject”[tiab] OR “research subjects”[tiab] OR “patient selection”[tiab] OR “human experimentation”[tiab] OR “Volunteers”[Mesh] OR “Patient Participation”[Mesh] OR “Research Subjects”[Mesh] OR “Human Experimentation”[Mesh] OR “Patient Selection”[mesh]) AND (ethic* OR exploit* OR “Ethics, Research”[Mesh] OR “undue inducement”[tiab] OR compensation[tiab] OR compensate*[tiab] OR incentive*[tiab]OR incentive*[tiab] OR “Compensation and Redress”[Mesh])

Clinical study + ethics + poverty

(“clinical trial”[tw] OR “clinical trials”[tw] OR “clinical study”[tiab] OR “clinical studies”[tiab] OR “clinical research”[tiab] OR “Clinical Studies as Topic”[Mesh] OR “human experimentation”[tiab] OR “Human Experimentation”[Mesh]) AND (subject[tiab] OR subjects[tiab] OR volunteer*[tiab] OR “patient participation”[tiab] OR “research subject”[tiab] OR “research subjects”[tiab] OR “patient selection”[tiab] OR “Volunteers”[Mesh] OR “Patient Participation”[Mesh] OR “Research Subjects”[Mesh] OR “Patient Selection”[mesh] OR participant[ti]) AND (ethic* OR exploit* OR “Ethics, Research”[Mesh] OR “undue inducement”[tiab] OR compensation[tiab] OR compensate*[tiab] OR incentive*[tiab] OR incentive*[tiab] OR “Compensation and Redress”[Mesh]) AND (“Poverty”[Mesh] OR poor[tiab] OR “low income”[tiab] OR disadvantaged[tiab] OR indigent[tiab] OR indigence[tiab] OR poverty[tiab] OR “socioeconomic disadvantage”[tiab] OR “socioeconomic disadvantaged”[tiab] OR underinsured OR uninsured)

Clinical study + ethics/compensation + poverty/uninsured + access to care

(“clinical trial”[tw] OR “clinical trials”[tw] OR “clinical study”[tiab] OR “clinical studies”[tiab] OR “clinical research”[tiab] OR “Clinical Studies as Topic”[Mesh] OR subject[tiab] OR subjects[tiab] OR volunteer*[tiab] OR “patient participation”[tiab] OR “research subject”[tiab] OR “research subjects”[tiab] OR “patient selection”[tiab] OR “human experimentation”[tiab] OR “Volunteers”[Mesh] OR “Patient Participation”[Mesh] OR “Research Subjects”[Mesh] OR “Human Experimentation”[Mesh] OR “Patient Selection”[mesh]) AND (ethic* OR exploit* OR “Ethics, Research”[Mesh] OR “undue inducement”[tiab] OR compensation[tiab] OR compensate*[tiab] OR incentive*[tiab] OR incentive*[tiab] OR “Compensation and Redress”[Mesh]) AND (“Poverty”[Mesh] OR poor[tiab] OR “low income”[tiab] OR disadvantaged[tiab] OR indigent[tiab] OR indigence[tiab] OR poverty[tiab] OR “socioeconomic disadvantage”[tiab] OR “socioeconomic disadvantaged”[tiab] OR underinsured OR uninsured) AND (“access to healthcare”[tiab] OR “access to care”[tiab] OR “fair benefits”[tw] OR “Delivery of Health Care”[mesh] OR “Health Services Accessibility”[mesh] OR “healthcare delivery”[tiab] OR “health services accessibility”[tiab] OR “post-trial access”[tiab])

References

- 1).Dal-Ré R, Rid A, Emanuel E, et al. The potential exploitation of research participants in high income countries who lack access to health care. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 81: 857–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Jacobson N, Krupp A and Bowers BJ. Planning for ancillary care provision: lessons from the developing world. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2016; 11: 129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Merritt MW. Health researchers’ ancillary care obligations in low-resource settings: how can we tell what is morally required? Kennedy Inst Ethics J 2011; 21: 311–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Flores G, Portillo A, Lin H, et al. A successful approach to minimizing attrition in racial/ethnic minority, low-income populations. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2017; 5: 168–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Geromanos K, Sunkle SN, Mauer MB, et al. Successful techniques for retaining a cohort of infants and children born to HIV-infected women: the Prospective P2C2 HIV study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2004; 15: 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Katz KS, El-Mohandes A, Johnson DM, et al. Retention of low income mothers in a parenting intervention study. J Community Health 2001; 26: 203–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Nicholson LM, Schwirian PM, Klein EG, et al. Recruitment and retention strategies in longitudinal clinical studies with low-income populations. Contemp Clin Trials 2011; 32: 353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Warner ET, Glasgow RE, Emmons KM, et al. Recruitment and retention of participants in a pragmatic randomized intervention trial at three community health clinics: Results and lessons learned. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Whiteman MK, Langenberg P, Kjerulff K, et al. A randomized trial of incentives to improve response rates to a mailed women’s health questionnaire. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003; 12: 821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Parks MJ, Slater JS, Rothman AJ, et al. Interpersonal communication and smoking cessation in the context of an incentive-based program: survey evidence from a telehealth Intervention in a low-income population. J Health Commun 2016; 21: 125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Parnes B, Main DS, Holcomb S, et al. Tobacco cessation counseling among underserved patients: a report from CaReNet. J Fam Pract 2002; 51: 65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Bradley CJ and Neumark D. Small cash incentives can encourage primary care visits by low-income people with new health care coverage. Health Affairs 2017; 36: 1376–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Bessman SC, Pham JC, Ding R, et al. Factors influencing completion of a follow-up telephone interview of emergency department patients one week after ED visit. Academic Emergency Medicine; 19: S198, https://insights.ovid.com/academic-emergency-medicine/acemd/2012/04/001/factors-influencing-completion-follow-telephone/371/00043480 (2012, accessed 12 May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14).Barnett JC and Berchick ER. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2016 44. [Google Scholar]

- 15).Kaiser Family Foundation. Key facts about the uninsured population Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, https://www.kff.org/uninsured/fact-sheet/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population (2017, accessed 12 May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 16).The Commonwealth Fund. Underinsured rate increased sharply in 2016; more than two of five marketplace enrollees and a quarter of people with employer health insurance plans are now underinsured. The Commonwealth Fund, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/press-releases/2017/oct/underinsured-press-release (2017, accessed 2 April 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 17).Auter Z U.S. Uninsured rate steady at 12.2% in fourth quarter of 2017. Gallup News, 16 January 2018, http://news.gallup.com/poll/225383/uninsured-rate-steady-fourth-quarter-2017.aspx (2018, accessed 12 May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18).Niu X, Roche LM, Pawlish KS, et al. Cancer survival disparities by health insurance status. Cancer Med 2013; 2: 403–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Nam S, Chesla C, Stotts NA, et al. Barriers to diabetes management: patient and provider factors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011; 93: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).McWilliams JM. Health consequences of uninsurance among adults in the United States: recent evidence and implications. Milbank Q 2009; 87: 443–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).American Society of Clinical Oncology. The state of cancer care in America, 2016: a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract 2016; 12: 339–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Markt SC, Lago-Hernandez CA, Miller RE, et al. Insurance status and disparities in disease presentation, treatment, and outcomes for men with germ cell tumors. Cancer 2016; 122: 3127–3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Fang J, Zhao G, Wang G, et al. Insurance status among adults with hypertension-the impact of underinsurance. J Am Heart Assoc. Epub ahead of print 21 December 2016. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Sommers BD, Gawande AA and Baicker K. Health insurance coverage and health - what the recent evidence tells us. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 586–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Woolhandler S and Himmelstein DU. The relationship of health insurance and mortality: is lack of insurance deadly? Ann Intern Med 2017; 167: 424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE, et al. Health insurance and mortality in US adults. Am J Public Health 2009; 99: 2289–2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).King WD, Wyatt GE, Liu H, et al. Pilot assessment of HIV gene therapy-hematopoietic stem cell clinical trial acceptability among minority patients and their advisors. J Natl Med Assoc 2010; 102: 1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Larkey LK, Gonzalez JA, Mar LE, et al. Latina recruitment for cancer prevention education via Community Based Participatory Research strategies. Contemp Clin Trials 2009; 30: 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Newman PA, Duan N, Roberts KJ, et al. HIV vaccine trial participation among ethnic minority communities: barriers, motivators, and implications for recruitment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 41: 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Ellis PM, Hobbs MK, Rikard-Bell GC, et al. General practitioners’ attitudes to randomised clinical trials for women with breast cancer. Med J Aust 1999; 171: 303–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Stunkel L and Grady C. More than money: a review of the literature examining healthy volunteer motivations. Contemp Clin Trials 2011; 32: 342–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Iltis AS. Payments to normal healthy volunteers in phase 1 trials: avoiding undue influence while distributing fairly the burdens of research participation. J Med Philos 2009; 34: 68–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer 2008; 112: 228–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Shavers-Hornaday VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF, et al. Why are African Americans underrepresented in medical research studies? Impediments to participation. Ethn Health 1997; 2: 31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Kolata G and Eichenwald K. STOPGAP MEDICINE: A special report: for the uninsured, drug trials are health care. The New York Times, 22 June 1999, https://www.nytimes.com/1999/06/22/business/stopgap-medicine-a-special-report-for-the-uninsured-drug-trials-are-health-care.html (1999, accessed 30 March 2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Clemmitt M Clinical researchers adapting to mandate for more diversity in study populations. The Scientist Magazine, 1991, https://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/12019/title/Clinical-Researchers-Adapting-To- Mandate-F or-More-Diversity-In-Study-Populations/ (1991, accessed 30 March 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 38).Farmer DF, Jackson SA, Camacho F, et al. Attitudes of African American and low socioeconomic status white women toward medical research. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2007; 18: 85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Gross CP, Filardo G, Mayne ST, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status and race on trial participation for older women with breast cancer. Cancer 2005; 103: 483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Grady C, Hampson LA, Wallen GR, et al. Exploring the ethics of clinical research in an urban community. Am J Public Health 2006; 96: 1996–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Humphreys K and Weisner C. Use of exclusion criteria in selecting research subjects and its effect on the generalizability of alcohol treatment outcome studies. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Mitchell AM and Kline JA. Systematic bias introduced by the informed consent process in a diagnostic research study. Acad Emerg Med 2008; 15: 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Nyamathi A, Koniak-Griffin D, Tallen L, et al. Use of community-based participatory research in preparing low income and homeless minority populations for future HIV vaccines. J Interprof Care 2004; 18: 369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).Slomka J, McCurdy S, Ratliff EA, et al. Perceptions of financial payment for research participation among African-American drug users in HIV Studies. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22:1403–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Webb DA, Coyne JC, Goldenberg RL, et al. Recruitment and retention of women in a large randomized control trial to reduce repeat preterm births: the Philadelphia Collaborative Preterm Prevention Project. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010; 10: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).El-Sadr W and Capps L. The challenge of minority recruitment in clinical trials for AIDS. JAMA 1992; 267: 954–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Guerrero M and Heller PL. Sociocultural limits in informed consent in dementia research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2003; 17 Suppl 1: S26–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Merrill JM. Access to high-tech health care. Ethics. Cancer 1991; 67: 1750–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Pace C, Miller FG and Danis M. Enrolling the uninsured in clinical trials: an ethical perspective. Crit Care Med 2003; 31: S121–S125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50).Stone TH. The invisible vulnerable: the economically and educationally disadvantaged subjects of clinical research. J Law Med Ethics 2003; 31: 149–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Vasgird DR, Hensleigh M, Berkman A, et al. Protecting the uninsured human research subject. J Public Health Manag Pract 2000; 6: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52).Welsh KA, Ballard E, Nash F, et al. Issues affecting minority participation in research studies of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1994; 8: 38–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53).Koblin BA, Heagerty P, Sheon A, et al. Readiness of high-risk populations in the HIV Network for Prevention Trials to participate in HIV vaccine efficacy trials in the United States. AIDS 1998; 12: 785–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).Sofaer N and Strech D. Reasons why post-trial access to trial drugs should, or need not be ensured to research participants: a systematic review. Public Health Ethics 2011; 4: 160–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55).Swanson GM and Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995; 87: 1747–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56).Fisher JA and Kalbaugh CA. Challenging assumptions about minority participation in US clinical research. Am J Public Health 2011; 101: 2217–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57).Fisher JA. Medical research for hire: the political economy of pharmaceutical clinical trials. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University; Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58).Joseph G and Dohan D. Recruitment practices and the politics of inclusion in cancer clinical trials. Med Anthropol Q 2012; 26: 338–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59).Emanuel EJ. Undue inducement: nonsense on stilts? Am J Bioeth 2005; 5: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60).Walter JK, Burke JF and Davis MM. Research participation by low-income and racial/ethnic minority groups: how payment may change the balance. Clin Transl Sci 2013; 6: 363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61).Dickert N and Grady C. What’s the price of a research subject? Approaches to payment for research participation. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]