Abstract

Self-templating propagation of protein aggregate conformations is increasingly becoming a significant factor in many neurological diseases. In Alzheimer disease (AD), intrinsically disordered amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides undergo aggregation that is sensitive to environmental conditions. High-molecular weight aggregates of Aβ that form insoluble fibrils are deposited as senile plaques in AD brains. However, low-molecular weight aggregates called soluble oligomers are known to be the primary toxic agents responsible for neuronal dysfunction. The aggregation process is highly stochastic, and involves both homotypic (Aβ-Aβ) and heterotypic (Aβ with interacting partners) interactions. Two of the important members of interacting partners are membrane lipids and surfactants, to which Aβ shows a perpetual association. Aβ–membrane interactions have been widely investigated for more than two decades, and this research has provided a wealth of information. Although this has greatly enriched our understanding, the objective of this review is to consolidate the information from the literature that collectively showcases the unique phenomenon of surfactant-mediated Aβ oligomer generation, which has largely remained inconspicuous. This is especially important because Aβ aggregate ‘strains’ are increasingly becoming relevant in light of the correlations between the structure of aggregates and AD phenotypes. Here, we will focus on aspects of Aβ-surfactant interactions specifically from the context of how surfactant modulation generates a wide variety of biophysically and biochemically distinct oligomer sub-types. This, we believe, will refocus our thinking on the influence of surfactants and open new approaches in delineating the mechanisms of AD pathogenesis.

Keywords: Amyloid-beta, surfactant, membrane, oligomer, strain, aggregation Aβ and Alzheimer disease pathology

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a fatal, progressive neurodegenerative disorder with clinical manifestations that include acute memory loss, cognitive decline and behavioral changes resulting in social inappropriateness. AD is the most common among all neurodegenerative disorders, with over five million people affected in the United States alone [1]. Without medicinal intervention, this number is expected to nearly triple by 2050 [1]. According to the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the death rates from AD dramatically climbed to 55% between 1999 and 2014, making viable diagnostic and therapeutic avenues a critical need [2]. Discovered by the Bavarian psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer in 1905, significant advancements in understanding AD only began to occur 7–8 decades later with the morphological understanding of two main pathological hallmark lesions in the AD brain: extracellular neuritic plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles. During the 1990s it became clear that two proteins, amyloid-β (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau, are the major components of plaques and tangles, respectively [3, 4].

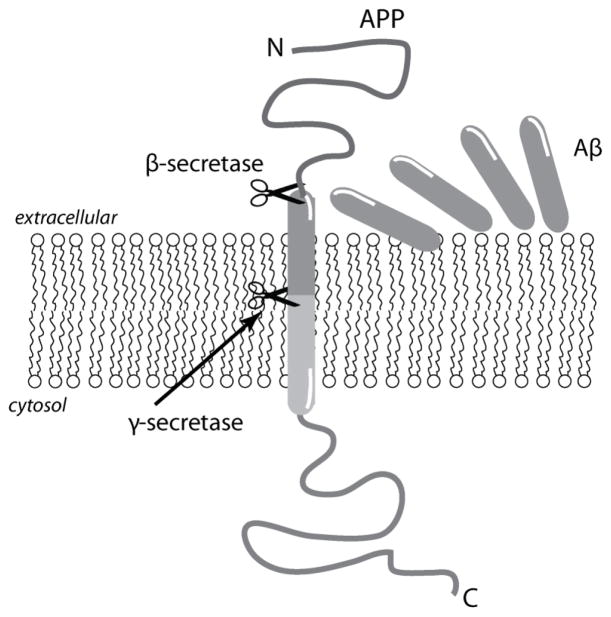

Aβ is generated by the proteolytic processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is abundant in the central nervous system but ubiquitously expressed in many cell types [5, 6]. APP is an integral membrane protein containing a single transmembrane domain, and the cleavage occurs sequentially by the aspartyl proteases, β- and γ-secretases (Figure 1). While β-secretase cleaves APP on the extracellular side, the γ-secretase complex hydrolyzes the protein within the transmembrane domain (Figure 1). The γ-secretase complex comprises the proteins Aph-1, presenelin-1 (PS1), presenelin-2 (PS2), and nicastrin, and has a broader specificity in cleavage that leads to the generation of multiple Aβ isoforms ranging from Aβ1-38 to Aβ1-43 [7]. The cleavage specificity of the γ-secretase complex is also controlled by genetic mutations in APP; however, the precise mechanism of the enzyme remains uncertain [8]. Among the isoforms, Aβ1-40 (Aβ40) is the predominant form followed by Aβ1-42 (Aβ42), but the latter is initially observed in diffuse amyloid aggregates [9] and is believed to be responsible for early synaptic and neuronal dysfunction in AD brains.

Figure 1.

Aβ generation by sequential protease cleavage involving β- and γ-secretases.

Aggregation of Aβ and significance of pathways

Spatiotemporal profile of Aβ aggregation

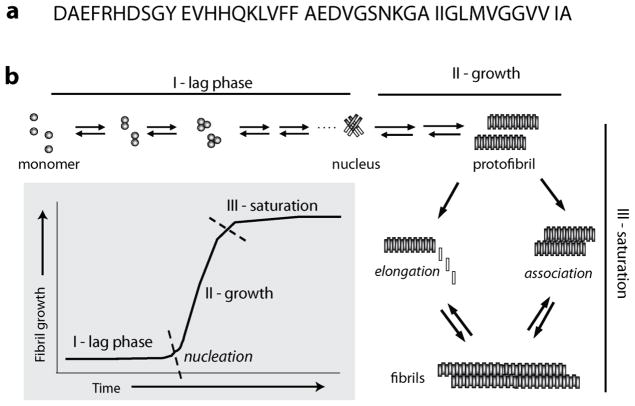

Upon cleavage from APP by aspartyl proteases, Aβ peptide is mainly released from the membrane into the extracellular matrix. The newly generated Aβ is intrinsically disordered, which is reflected in its random coil conformation [10–12]. The monomeric Aβ is highly susceptible to aggregating with other Aβ molecules, and does so almost spontaneously upon its generation from APP. Aggregation of Aβ is a nucleation-dependent process that follows a sigmoidal growth kinetics with the formation of a critical mass of aggregates called nucleus, being obligatory for the emergence of mature fibrils (Figure 2). A schematic of homotypic Aβ aggregation shows three broadly-defined phases of aggregation, namely a lag phase (I), growth phase (II) and a saturation phase (III) (Figure 2). The lag phase of aggregation is perhaps the most important phase during aggregation from a physiological perspective, as elaborated later in this manuscript, and is mechanistically the most confounding of all the phases. Although there is consensus regarding the formation of a nucleus during the lag phase, uncertainty remains about the nature of nucleus; whether it is heterogeneous or homogenous [13], or whether there is a single nucleation event or multiple events [14–17]. In sum, one could describe the lag phase of aggregation as being in dynamic flux dominated by stochastic interactions between Aβ conformeric ensembles until an ordered, relatively stable nucleus (or nuclei) is (are) formed. Once the prerequisite and a critical aggregate size is achieved (I in Figure 2), the propagation phase ensues with forward rates involving predominantly aggregate – monomer interactions that result in an exponential increase in the rates of aggregation towards high molecular weight protofibrils (II in Figure 2), which then form insoluble fibrils in the saturation phase (III in Figure 2) [18, 19].

Figure 2.

Protein sequence of Aβ1-42 protein (a) and schematic of aggregation reaction involving pure homotypic (Aβ-Aβ) interactions.

This aggregation mechanism, although consistent with numerous reports, does not represent the complete picture of the aggregation landscape. As previously described by Radford and others [20, 21], protein aggregation and amyloid formation in itself is an alternate pathway during protein folding. In a typical aggregation pathway, smaller oligomers are formed transiently along the fibril formation pathway that ‘roll down’ the energy landscape towards energetically favorable fibrils. In reality, even within the energy landscape along the ‘aggregation funnel’ there are many different pathways containing several kinetic traps in which specific conformeric and structurally variant species could be present. Indeed, it has become evident that there are alternative pathways and kinetic traps along the aggregation pathway [22, 23], and that neurotoxic oligomers can also be populated via such alternate pathways [24–27]. As mentioned earlier, the early stages of aggregation (lag phase), being dominated by homotypic and heterotypic stochastic interactions, could likely contain numerous kinetic traps. An obvious characteristic of such traps is that the oligomeric aggregates that are formed may differ in their conformation, degree of aggregation (number of monomers within the assembly), heterogeneity, or all of these factors. Such differences within these aggregates could manifest in differences in their ability to seed the propagation of fibrils. Thus, depending on the number of such conformeric strains, fibrils are formed via different pathways displaying structural heterogeneity and polymorphism [28]. This has been further elaborated in the concluding sub-section of this manuscript.

Aβ aggregate structure and AD phenotypes

Aβ aggregation is strongly driven by both homotypic (Aβ-Aβ) and heterotypic (Aβ-solvent and/or Aβ-solute) interactions. Because of stochasticity, the lag phase is highly susceptible to heterotypic interactions with other solutes present in the system. From years of research, we have known that the Aβ ‘interactome’ includes a variety of agents such as metal ions [29, 30], protein binding partners [31, 32], natural products and metabolites [33–37], as well as lipids and surfactants (as elaborated in this article). Therefore, heterotypic interactions with any Aβ interactome molecules have the potential to change the conformation of Aβ during the lag phase and alter the pathway of aggregation, which could result in multiple conformational variants of aggregates with distinct biochemical and cellular properties. Manifestations of conformational and morphological differences in cellular toxicity have been established in the past [38, 39]. The significance of Aβ fibril structure and morphology in AD is becoming far more critical than originally thought. Somewhat similar to the observations in prion diseases [40, 41], structure-to-phenotype correlations are beginning to emerge. Recently, using brain-derived fibrils as seeds, the Tycko laboratory has elegantly established that clinical phenotypic differences, especially those leading to rapid-onset AD (rAD), could emerge in part from the structure and morphology of the propagating fibrils [42, 43]. Along similar lines, Cohen et al. have reported conformationally-distinct Aβ aggregates in rAD cases as compared with typical AD [44]. In recent reports by the Jucker and Prusiner laboratories, the authors revealed structural variations in etiological subtypes of AD brains on the basis of their ability to bind fluorescent probes [45, 46]. Prion-like propagation of Aβ has now been well understood from the demonstration that intracerebral injection of endogenous Aβ seeds induces widespread deposition of Aβ in transgenic mice [47–53]. Inoculations in such experiments either used Aβ-laden brain homogenates or exogenous fibrils as seeds, and therefore, structural diversity of fibril seeds has mainly been attributed to propagation behavior of the seeds [51, 54, 55].

Lipids and membranes could be important members of the Aβ interactome

The main focus of this review is to bring forth how lipids and surfactants are able to modulate the aggregation behavior of Aβ to generate a multitude of structurally and functionally different aggregates depending on the physiochemical nature of the surfactant. The affinity of Aβ peptides for membranes becomes obvious when one looks at the generation of the peptides, as described above. The C-terminal sequence of Aβ within APP is buried in the phospholipid bilayer, while the N-terminal remains outside. This is reflected in the sequence of the peptide with the N-terminal side of the peptide containing many polar amino acids and the C-terminus containing a majority of hydrophobic residues (Figure 2). The amphipathic nature of Aβ peptides uniquely presents itself to preferential interactions with interfaces such as liquid-gaseous (water-air), liquid-solid (solvent-surface) and liquid-liquid (phase separated). In this context, there is a high likelihood of amphipathic lipids and other surfactants to interact with Aβ by providing a template for aggregation. When Aβ is released as a soluble monomer, charged membranes act as two-dimensional aggregation-templates to initiate accumulation of surface-associated Aβ, typically to augment aggregation into neurotoxic structures [56].

Interaction and modulation of Aβ aggregation by lipids

a. Interactions with bilayer-forming lipids

A wealth of information has been generated from over two decades of research on the interactions of Aβ with membrane surfactants. The amphipathic Aβ peptide shows strong affinity for membranes, and such heterotypic interactions may affect early steps of Aβ aggregation significantly [57–62]. First, we will focus on the surfactants (lipids) containing two fatty acid acyl chains that predominantly form a lipid bilayer. In pathological contexts, lipid membranes, sub-cellular organelle surfaces, synaptic vesicles, lipid rafts as well as endo- and exosomes can significantly affect Aβ aggregation by accelerating and nucleating fibril formation, generating and stabilizing specific oligomers and even promoting polymorphic aggregates.

Interactions leading to pore formation and membrane disruption

One of the widely investigated phenomena of Aβ-membrane interactions is the insertion of Aβ into the membranes and subsequent disruption. Importantly, Aβ has been long known to form Ca(II) permeable channels in the membrane [63, 64]. Association of Aβ with anionic lipid monolayers has been observed leading to partial insertion of Aβ into the membrane [65]. Such an interaction consequently promotes aggregation to Aβ fibrils [66]. Investigation of such mechanisms by Aβ40 using NMR spectroscopy indicated that the N-terminal region is unstructured while the C-terminal hydrophobic region adopts anα-helical conformation [67]. The two regions are separated by a kink, which is significant in membrane insertion [67]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to model the interactions between Aβ oligomers and membranes showed formation of ion channels with two different topologies, suggesting a modulatory effect of the membranes on Aβ structure and conformation. More importantly, Aβ oligomers have now been widely understood to form pores in both synthetic as well as cellular membranes, capable of generating conductance and classical channel activity [64, 68, 69]. Both Aβ monomers reconstituted with lipids as well as pre-formed oligomers deposited on to synthetic or brain-derived lipids formed channels [70, 71]. In addition, experimental observation of the effect of this channel on Ca2+ selectivity was supported by such models [72, 73]. Another study using MD simulations on Aβ42 peptide monomers and oligomers identified insertion into the lipid bilayer in agreement with other reports [74]. These theoretical results were also consistent with the experimental observation that Aβ forms a cation selective channel in both synthetic lipid-bilayers [75] and cellular membranes[76]. However, it remains unknown whether the all oligomers are able to form channels in the membrane, and whether oligomer conformation capable of pore formation is induced by the interaction with lipid surfaces, which that precedes it. Such is the case with zwitterionic lipids, to which a conserved region (K16-E22) within the central region of Aβ bound to lipid surface prior to surface-catalyzed Aβ fibril formation and transmembrane pore formation [77].

Interactions on lipid surfaces

Interactions of Aβ with lipid surfaces have been investigated by using many different models including solid support, self-assembled monolayers, and membrane-mimics [78–80]. Many reports indicate that Aβ interactions with the anionic phospholipids on reconstituted liposomes and unilamillar vesicles are largely limited to the lipid surface at neutral pH [58, 81, 82]. In one report, anionic phospholipids increased the fibrillation of Aβ, while neutral, zwitterionic, and lipids lacking phosphate groups did not show significant effect on Aβ fibrillation rates [83]. Investigation into the effects of surface charges on Aβ aggregation using zwitterionic (2-dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) or 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3 –phosphocholine (DOPC)), anionic (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero- 3–[phospho-rac-(3-lysyl(1-glycerol)] (DOPG)) and cationic (1,2- dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-methylammonium-propane (DOTAP)) lipids led to the finding that Aβ aggregated in zwitterionic DPPC and anionic DOPG, while it inserted and disrupted the membranes of cationic DOTAP and zwitterionic DOPC [84]. In one report, aggregation of Aβ on zwitterionic DOPC LUVs by FRET analysis indicated that the liposomes were able to catalyze fibril formation via secondary nucleation mechanisms involving aggregate fragmentation [85]. This report also revealed that the binding on the lipid surface was restricted to only aggregated Aβ and not the monomer, suggesting secondary pathways induced by oligomeric forms of Aβ on the membrane surface. In negatively charged lipids, Aβ40 oligomer binding was dependent on surface charges, while membrane insertion was dictated by membrane rigidity, and both processes were clearly distinct [86]. MD simulations involving Aβ peptides and the phospholipid bilayer using DPPC and dioleoyl phosphotidylserine (DOPS) vesicles showed fibril promotion on the surface of the membrane lipids because of the peptide re-distribution on the surface via charged interactions, exhibiting an auto-regulation type behavior [87]. The interactions of Aβ with membranes depend not only on the former’s structure and conformational state, but also on reaction conditions. Good et al. observed that Aβ-liposome interactions were higher for Aβ aggregates than monomeric Aβ [88]. They found that Aβ aggregates bind to both cortical homogenates and membranes, whereas Aβ monomers bind to homogenates only. However, another report using different experimental conditions revealed that monomeric Aβ bound rapidly to liposomes, while the Aβ aggregates bind slowly [89]. An MD simulation study on the interactions of a pre-formed Aβ42 tetramer on POPC membranes showed that the tetramers were elongated, and changed their overall structure upon interaction with the membrane surface [90], suggesting that the membrane surface characteristics play an important role in Aβ aggregate structure. Overall, these reports indicate the surface characteristics of membranes, which are mainly dominated by the lipid head groups, behave as specificity inducing factors for Aβ oligomer conformations during aggregation

b. Interactions of Aβ with micelle-forming lipids

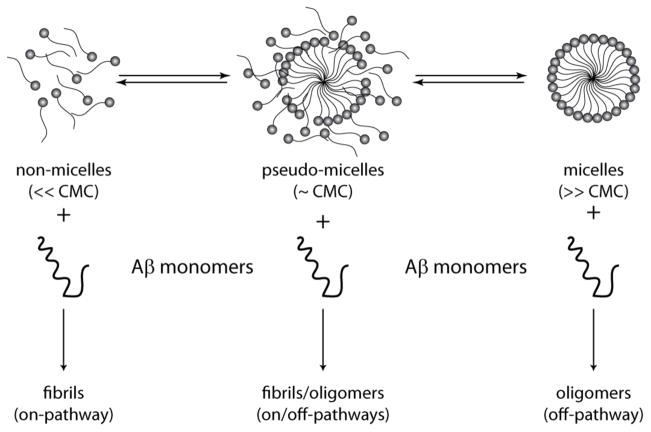

As a rule of thumb, lipids containing a single acyl chain tend to form micelles as opposed to a bilayer. Similar to the liposomal systems, micelles as membrane-mimicking environments have also provided a wealth of information on a mechanistic understanding of Aβ – lipid interactions. Anionic surfactants such as sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), often used as denaturants, have been used as model polar-nonpolar interfaces to investigate the aggregation of Aβ and other amyloid proteins [67, 91–95]. Yamamoto and colleagues investigated the effect of neutral, zwitterionic and anionic surfactants on Aβ aggregation and found that all three surfactants were able to augment Aβ40 and Aβ42 aggregation in a concentration-dependent manner [92]. The effects of surfactants on the two peptides varied, with Aβ42 showing more pronounced aggregation than Aβ40. More importantly, the aggregation behavior of the peptides showed strong dependence on surfactant concentration. Only in a narrow range of concentrations below its critical micelle concentration (CMC), SDS was able to augment Aβ42 aggregation without any observable lag time [92]. Based on the idea that micellar interfaces uniquely affect Aβ aggregation, Nichols and coworkers demonstrated the phenomena of interfacial aggregation using model interfaces composed of dilute hexafluoro isopropanol (HFIP) as well as buffer-chloroform [96, 97]. They elegantly showed that Aβ aggregation is preferentially augmented at the polar – non-polar interfaces. Similar to Yamamoto and co-workers, Rangachari et al. also demonstrated that SDS accelerates Aβ40 aggregation in a concentration-dependent manner and compared the similarities to aggregates formed in HFIP interfaces [93]. While near-CMC SDS promoted β-sheet conformations and fibrillar aggregates, micellar SDS above the CMC stabilized Aβ40 in an α-helical conformation. Furthermore, near the CMC, Aβ40 initially adopted an α-helical conformation corresponding to amorphous oligomers, which eventually converted into β-sheet fibrils over time. Similar structural transitions from α-helix to β-sheet with a concomitant increase in fibril formation were also observed with Aβ40 in the presence of DPC surfactants [98]. Rangachari and co-workers also demonstrated the effects of SDS on Aβ42 aggregation, which was dependent on SDS concentration [99]. However, unlike Aβ40, within a narrow range of SDS concentrations, soluble Aβ42 oligomers were formed along a pathway different from fibril formation, which was strictly dependent on the CMC of SDS [99]. This observation parallels the one on well-characterized, 60 kDa ‘Aβ globulomers’ which are also formed along a pathway that is independent of the fibril formation pathway [100, 101]. It is noteworthy that globulomers are generated in the presence of 0.2% SDS, which is close to its CMC. Moreover, globulomers are shown to be neurotoxic by specifically blocking long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal slices [100]. Characterization of SDS-derived off-pathway oligomers showed a unique structure by NMR spectroscopy [102, 103]. Studies using DHPCs as micellar surfactants also showed modulation of aggregation based on their CMCs - enhancement of fibril formation was observed at submicellar concentrations (below CMC), while micellar concentrations (above CMC) stabilize Aβ in an α-helical conformation [104]. Non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) have been used as model surfactants to investigate their effects on Aβ42 aggregation. Similar to those observed with SDS, NEFAs also induce concentration-dependent effects on Aβ. Three broadly categorized regimes based on the respective CMCs of NEFAs such as below, near and above CMC, either augmented or inhibited Aβ42 aggregation [105]. Only at near and above the CMCs did NEFAs induce oligomers of Aβ42 via alternative pathways, while enhancement of fibril formation was observed below the CMC [105, 106].

c. Modulation of aggregation by lipids and membrane constituents

Evidence for lipid involvement in Aβ modulation

The effects of Aβ interaction with lipids are diverse. Perhaps the most significant of them all is the ability of membrane lipids to modulate Aβ aggregation pathways in generating polymorphic aggregates and many oligomer strains. Numerous reports over the last decade using reconstituted phospholipid vesicles indicate formation of aggregates along off-fibril forming pathways, paving a way for the generation of structurally-diverse oligomers [107–109]. Recently, Aβ42 aggregation on SUV and large unilamellar vesicles (LUV) from POPC lipids showed formation of polymorphic aggregates with distinct biophysical characteristics [110]. In this study, LUVs with high POPC concentrations suppressed amyloid formation that affected fibrillation kinetics, as opposed to those with low POPC concentrations, demonstrating the effect of concentration gradients along the liposome surface in modulating aggregation pathways. To investigate the effect of membrane thickness on Aβ aggregation, Korshavn et al used bilayers formed by the short-chain 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DLPC) lipid as a model for disease bilayers, while 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) as a model of normal bilayers [111]. They found that DLPC-assisted oligomers could disrupt the membranes more effectively than those generated from POPC vesicles, providing evidence for the deleterious effects of reduced membrane thickness. In one report, zwitterionic lipid vesicles not only promoted Aβ42 aggregation, they did so by interacting specifically with the growing fibrils, showing aggregate-specific interaction of these lipids [85]. Furthermore, these lipid vesicles were thought to augment monomer-dependent secondary nucleation at the surface of existing fibrils and facilitate monomer-independent catalytic processes consistent with fibril fragmentation and concomitant secondary aggregation pathways [85]. In a different study, it was also noted that Aβ aggregates formed in solution could present a different structure and toxicity upon interacting with the membranes [112]. It appears as though PG lipids modify the aggregation process and induce toxic oligomers independently from the fibrils along ‘off-pathways’, and their formation is enhanced by the presence of OH groups on the membrane surface [113]. In our laboratory, we have demonstrated the generation of off-pathway oligomers in the presence of NEFAs, which show distinct biophysical and pathological properties from on-pathway fibrils [114–116]. We have also shown that the aggregation pathway is dependent on the surfactant-Aβ ratio [105, 117]. Thus, given the mobility of cell membranes and lipid rafts in cellular environments, because of which charge concentration variations develop along the cell surface, it is highly likely that such surfactant interfaces are able to induce similar effects on Aβ aggregation. Some of the aforementioned reports establish the fact that the physicochemical composition and concentration of the membranes lead to different specificities of interaction among Aβ aggregates, and promote aggregation in various ways. The data also suggest that oligomers formed along off-fibril formation pathways, which may structurally differ from their on-pathway counterparts, could exhibit different interaction regimes with the membrane.

Modulatory effects were also observed for physiological lipids derived from endogenous sources. First, toxic oligomeric Aβ has been observed in patients with AD [118], HCHWA-D [119], and after fatal head injury [120] were found to be associated with membrane lipids as complexes, suggesting a strong interaction between Aβ oligomers and lipids. Aβ deposition in a form bound to plasma membranes resulted in the formation of non-fibrillar diffuse aggregates [121]. In their investigation into the interactions of Aβ with GM1-containing liposomes, Hayashi and co-workers observed that Aβ peptides showed altered aggregation kinetics with detectable protofibrils [57]. They concluded that this is due to the altered conformation adopted by Aβ in the presence of liposomes, which drives the aggregation into an alternate pathway. Aβ42 interactions with brain-derived lipids also resulted in an exclusive formation of small aggregates without any fibrils, suggesting generation and stabilization of off-pathway oligomers. A similar observation was also made with the co-incubation of Aβ with lipid rafts isolated from brain tissues in which a rapid formation of tetrameric Aβ was identified without the appearance of fibrils even after long incubation times, indicating the generation and stabilization of oligomers potentially as an off-pathway species [122].

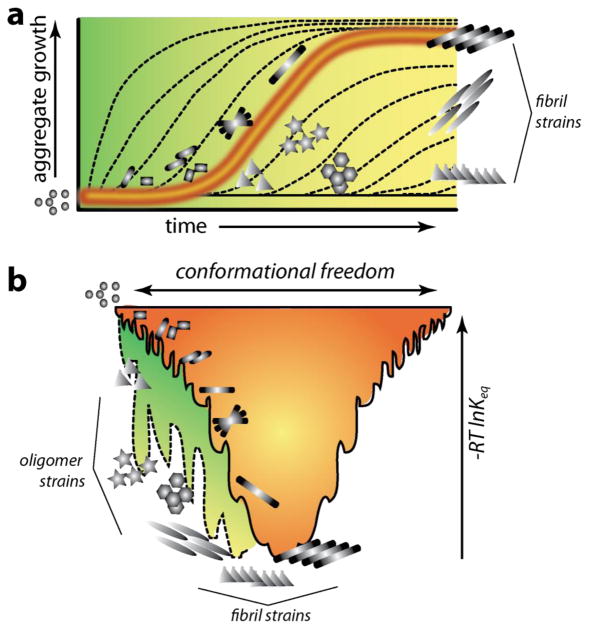

Evidence of modulation based on temporal models

Modulation of aggregation pathways to populate both oligomers and fibrils was also observed using non-physiological models of anionic, cationic and neutral surfactants, further emphasizing the potential role of surfactants in the modulation of aggregation [123, 124]. Figure 3 summarizes the dynamics of Aβ-surfactant interactions reported earlier [117]. One of the main signatures of oligomers formed along the off-fibril formation pathways is the temporal kinetics. ‘Off-pathway’ aggregates tend to have a longer half-life and are slow in converting to fibrils because of their potential stabilization in kinetics traps (Figure 4). To gain insights into the formation and decay of such aggregates, temporal modeling is necessary. Over the years, mathematical models and simulations have provided some important insights into the complex temporal behavior of Aβ aggregation and modulation, but such models largely remain sparse. Mathematical models have been applied to simulate the kinetics of different types of protein aggregation pathways including amyloid proteins [125–128]. Such models can be broadly categorized into kinetic, empirical and their variants such as the Finke-Watzky (F-W) kinetic model [129]. Unfortunately, very few models have considered amyloid and lipid/membrane interactions and their effects in protein aggregation. In her paper, Murphy stated the urgency and importance of such modeling approaches[130]: “Elucidation of the intricate kinetic interplay between amyloidogenesis and membranes provides a challenge that will need to be addressed to completely ascertain the role of membranes in amyloid disease pathology.” To our knowledge, the first mathematical formulation to consider temporal modulation of aggregation involving competition between on- and off-pathway was presented by Powers et al [131]. The specific effects of lipids/membranes on the structure of Aβ oligomers were not studied in this work; however, the bulk effects of lipids/membranes on aggregation behavior were modeled through fitting the experimental data. In this model, the monomers were considered to aggregate via two different, mutually exclusive pathways involving fibril formation (on) and oligomer formation (off). The off-pathway considers structurally different monomers (formed by membrane/lipid interactions) that proceed to form higher molecular weight oligomers that are structurally different from their on-pathway counterparts. This study elegantly demonstrated the see-saw effect of two mutually competing pathways, laying a foundation for simulating such dynamics in Aβ aggregation. Friedman et al modeled dynamics of amphipathic peptide aggregation in the presence of surfactants [132]. They showed that there are two specific states, aggregation prone and aggregation protected, which correlate with the extent of aggregation. This work further supports the premise that by altering surfactant to peptide ratio one could generate different aggregates. Recently, our work on Aβ – NEFA interactions considers a modification of the Powers’ model to incorporate the effects of fatty acids on fibril formation and off-pathway micellar dynamics [117]. In this work, the combined on-pathway and off-pathway dynamics were modeled. The models from these computations establish a competition between the on- and off-pathway reactions with the outcome of aggregation pathway clearly dependent upon the surfactant concentration and phase transitions [117].

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram showing modulation of Aβ aggregation pathways by micelle-forming lipids (adapted from [117]). Lipid and surfactants show dynamics involving three categorized phases depending on their equilibrium concentrations: below critical micelle concentrations (CMC), they exist predominantly in the non-micellar form while at high CMC they are present as micelles. Near their CMCs, they exist in unstable and dynamic “pseudo-micellar” form. Binding of Aβ to these forms could change the lipid phase-transition dynamics that result in modulation of aggregation pathways distinctly.

Figure 4.

Kinetic and thermodynamic profiles of Aβ aggregation pathways in the absence (orange) and in the presence of (green) surfactants. a) Homotypic aggregation (Aβ-Aβ) in the absence of any interacting partners such as lipids, typically displays a sigmoidal growth curve (orange) with lag phase, growth phase and saturation (on-pathway). Heterotypic aggregation (Aβ-surfactants) is significantly altered (represented as dashed lines along a green background) depending on the nature of lipids (off-pathway). Such alteration of pathways leads to different oligomer and fibrils strains. b) Aggregation funnel represented in terms of energy landscape for homotypic (orange) and heterotypic (green) interactions.

Membrane components involved in the modulation of Aβ aggregation

Despite the establishment of possible alternative pathways of aggregation and stabilization of oligomers, it remains unclear what molecular factors precisely control Aβ to adopt multiple aggregation pathways. However, many reports do suggest several key players that may play a role in the modulation of aggregation. An early report on Aβ aggregation in the presence of different sub-cellular organelle membranes showed accelerated fibril formation by endosomal and lysosomal membranes while it was inhibited by Golgi membranes, which promoted oligomers exclusively [133]. This report brought out the fact that lipid constitution could be key in dynamic regulation of Aβ aggregation pathways. In another report, the investigators show that the presence of cholesterol within membranes influences the membrane fluidity, which in turn could control the outcome of their interactions with Aβ leading to the adoption of alternate aggregation pathways and polymorphic aggregates [134]. Several other reports have indicated both GM1 and cholesterol as key factors affecting the Aβ fibrillation on membranes. Aβ is known to recognize cholesterol-dependent clusters of GM1-containing liposomes [135], and aggregation kinetics and pathways are found to be strictly controlled by cholesterol and ganglioside amounts within the liposomes [58]. Although the nature of GM1 ganglioside interaction with Aβ remains controversial, the involvement of GM1 gangliosides in Aβ aggregation was unambiguously established when pretreatment of brain-derived GM1-containing liposomes with CTxB, a GM1 ligand, showed inhibition of Aβ fibrillation [136]. Furthermore, liposome-containing clusters of highly dense GM1 transformed Aβ into toxic oligomers without noticeable fibrils, indicate the modulatory effects of GM1 on Aβ aggregation [137–140]. In a MD simulation study, GM1 interactions with Aβ and POPC and palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidyl ethanolamine (POPE) membranes lead to the release of Aβ from the membranes, further envisaging the diverse effect GM1 can cause on Aβ [141]. In addition, single molecule experiments on live neuroblastoma cells showed that interaction of gangliosides with Aβ42 led to the formation of at least two oligomeric forms with distinct biophysical and structural differences that show different cytotoxicities [140]. Mechanistically, ganglioside clusters seem to offer a unique platform at their hydrophobic/hydrophilic interface for binding of Aβ molecules and confining their spatial movements to promote aggregation on the ganglioside clusters [142]. Furthermore, membrane curvature also seems to play a role in modulating aggregation [143], which parallels some of the observations on membrane rigidity and fluidity both as cause and consequence of Aβ interactions [144–146]. In a recent review, Cebecauer et al. elegantly presented a unifying view on the concentration-dependent modulatory effects of gangliosides on Aβ aggregation and oligomer formation [147]. Furthermore, simulations also reveal and support experimental observations that chemical composition of the membrane also affects the Aβ-lipid interactions. For example, low cholesterol content and increased membrane fluidity results in partial Aβ membrane insertion, while at high cholesterol content, Aβ diffuses into a more rigid membrane resulting in higher Aβ membrane associations [147]. In a separate study, Evengelisti et al studied the cytotoxic effects of protein oligomers on membranes and came to the conclusion that toxicity not only depends on the nature of oligomers but also on the chemical composition of the membranes that they interact with [148]. The same principle seems to hold true for other amyloid proteins including Aβ.

Consequence of Aβ-lipid interactions

a. Cellular toxicity

Three broadly categorized mechanisms of oligomer-induced neurotoxicity have been revealed by prior research [149]. a) extracellular Aβ aggregates can bind to various receptors leading to the activation of signaling pathways. b) Aβ oligomers can form membrane pores or channels [64] leading to cell death, known as the “channel hypothesis” [150, 151]. c) Oligomers can be transported within the cells to induce dysfunction of mitochondria, lysosome and breakdown of other cellular processes. While these mechanisms have been recently reviewed by Kotler et al and Kayed et al [152] and [149], there are a few points worth noting here. First, the receptor-mediated mechanism postulated by many reports involving receptors such as advanced glycation end (AGE) products, nerve growth factor (NGF), NMDA, and NF-κB, underscores the involvement and importance of structurally diverse oligomers in neurotoxicity. A report by Kourie et al. investigated over 100 channels formed by Aβ40, which could be grouped into one of four categories based on conductance, kinetics, selectivity, and pharmacological properties of the pores [153]. This report showed that heterogeneity of Aβ can manifest in part to the pore forming structure of aggregates and their toxicity. More recently Serra-Batiste and co-workers generated a 60 kDa oligomer of Aβ42 in high concentrations of DPC micelles, which upon addition to lipid bilayers formed β-sheet rich nanopores [154]. These oligomers were similar in size to the SDS-generated Aβ globulomers, which have been shown to inhibit long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices [100]. This reveals that lipids can mediate the formation of pore-forming oligomers, which are implicated in neurotoxicity. Another method by which Aβ induces toxicity is by modulating membrane fluidity and conductance. Increase of membrane conductance by several different soluble oligomers (and not monomers or fibrils) was reported, and occurred without the formation of pores [155]. A report by Kremer et al. on membrane fluidity changes during Aβ aggregation revealed that aggregates, but not monomers, decreased membrane fluidity, the extent of which could be correlated to aggregate growth [144], in agreement with other reports [156, 157]. Vestergaard et al. have investigated the effect that Aβ aggregates have on modulating membrane morphology and fusion events, and revealed that Aβ42 oligomers localize more closely than fibrils to mediate fusion of LUVs with GUVs [158]. Furthermore, Aβ42 oligomers have also been shown to promote oxidative lipid damage [159] and disrupt membrane integrity [111, 113]. The C-terminal fragment (29–42) of Aβ has been shown to form β-sheet aggregates in the presence of lipid bilayers (PC/PE (2:1) SUVs), which induced cellular apoptosis by fragmenting DNA and activating Caspase-3 in PC-12 cells [160]. Along similar lines, Marzesco et al. have demonstrated the potency of membrane-associated Aβ through inoculation in transgenic mice [161]. Work from Wang and co-workers has shown that Aβ-induced toxicity can be reduced by inhibiting cholesterol and ganglioside synthesis in PC-12 cells [162]. Some of the aforementioned reports signify the roles of a wide variety of oligomer assemblies with distinct conformations, which were generated under the influence of membrane lipids that manifest in a wide variety of different cellular responses depending oligomer structure.

b. Oligomer strains and phenotypic outcomes

A wave of recent research, driven by pathologic similarities between prion diseases and AD [163], supports the hypothesis that corruptive protein templating, or seeding, is a prime mover of disease propagation. Although it is unclear whether AD is infectious as are prion diseases, Aβ, like prions, can form polymorphic and polyfunctional strains [51]. Several lines of evidence collectively argue that aggregated Aβ in the brain extract is critical for in vivo seeding and the phenotype of the induced Aβ deposits mirrors that of the deposits in the extract, suggesting an Aβ-templating mechanism [48]. Indeed, a large body of work has demonstrated that intracerebral injection of endogenous Aβ seeds induces widespread deposition of Aβ in transgenic mice [47–53]. Inoculations in such experiments used either Aβ-laden brain homogenates or exogenous fibrils as seeds. Strain-specific propagation of aggregates and their eventual physiopathological fates are starting to correlate with the structure of the propagation units [164–167]. Recently, the Tycko laboratory elegantly established that phenotype differences could indeed emerge in part from Aβ fibril structure and morphology by propagating fibrils using brain derived fibrils as seeds [42, 43]. However, correlation between oligomer strains and fibril morphology vis-à-vis phenotypes remains elusive. Heterogeneity and diversity among oligomers, as well as the difficulty in their isolation as discrete units has, to a large extent, impeded our understanding of oligomeric structures and their behavior. This is especially true in the context of diverse strains generated in the presence of lipids, which remains largely unexplored. Other manifestations of oligomer strains may involve cross-propagation of other amyloidogenic proteins leading to exacerbation and/or clinically observed co-pathological phenotypes [168–171].

Summary and Perspectives

It has now been established that many interacting partners including lipids, metal ions, proteins and natural products influence the structure and aggregation of Aβ. Lipids are perhaps the most important and are the very first family of molecules to interact with Aβ mainly because of their perpetual association. As detailed above, lipids and Aβ can reciprocally affect each other. While Aβ can affect lipid structure and cause membrane disruption, pore formation and damage, lipid constitution and its physicochemical character can induce conformational changes to Aβ and catalyze the formation of diverse oligomers. Being an IDP, the structural plasticity of monomeric Aβ, together with its amphipathic character, makes it highly susceptible for structural transitions and modifications by lipids with significant physiological consequences. Lipid-Aβ interactions have particularly become relevant in light of the recent findings that similar to prions, polymorphic aggregates could behave as distinct strains in imparting phenotypic differences in AD brains [167]. The conformationally-distinct oligomers seed Aβ aggregation by recruiting disordered monomers towards aggregates with specific morphology. One of the defining events in the generation of stable, structurally-distinct oligomer seeds during the early stages of aggregation is the interaction of monomers with lipids. As elaborated above, membranes play a crucial role in initial structural transitions of Aβ. Depending on the nature of interactions between Aβ and membranes, oligomer seed-dependent propagation of aggregates towards various different structural forms results in discrete, structure-based cellular responses.

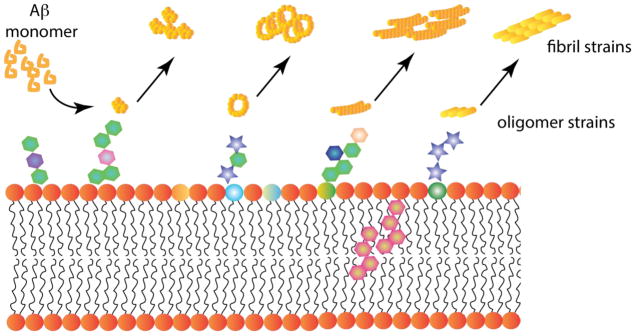

We now can realign our ideas on how membranes and lipids could influence the aggregation and consequently AD pathogenesis. As schematically shown in Figure 4a, temporal evolution of purely homotypic Aβ aggregation displays a sigmoidal growth curve (orange trace; Figure 4a). Depending on parameters such as charge distribution, phase transition, rigidity, and hydropathy, surfactants can alter this temporal evolution of aggregates either by augmenting or inhibiting it (dashed lines; Figure 4a). One obvious consequence of such effects is the generation of conformationally-changed aggregates, which may propagate their structure in many ways leading to distinct strains. This phenomenon could also be understood based on a thermodynamic perspective also as shown in Figure 4b. Here, the so called ‘aggregation funnel’ in orange represents purely homotypic Aβ aggregation without the influence of surfactants. The introduction of heterotypic interactions changes the free energy landscape to accommodate and direct many conformational strains into deeper kinetic pits (green area; Figure 4b). Scenarios by which surfactant-mediated strains can be generated are schematically depicted in Figure 5. Monomer interaction with different surfactant composition and chemistry may lead to the formation of oligomer strains, which can propagate into morphologically-distinct fibril strains (Figure 5). Such strains could interact and propagate differently to generate a multitude of strains with potentially diverse pathological effects. Keeping such a picture in mind, one can see a correlation between dynamic changes in aggregation and diversity in cellular response of Aβ aggregates. The diverse cellular effects in turn emerge from diversity in aggregate structures, visà-vis strains. Systematic structure-receptor correlations are yet to be clearly established, which may provide a much deeper understanding into the emergence of phenotypic differences from conformational strains. Nevertheless, as described above, a careful analysis of the large volume of literature on Aβ-membrane interactions generated over 2–3 decades indicates a conspicuous pattern involving a modulatory role and a catalytic role of surfactants in generating key oligomer strains. However, more needs to be done to ascertain unambiguously a clear cause-and-effect role of surfactants on phenotypic divergence in AD, which perhaps holds the fundamental basis for all Aβ-related pathologies.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of interactions between Aβ and surfactants leading to strain generation. Based on the many reports detailed in this manuscript, the interaction of Aβ monomers with lipids are initiated by the surface interactions, which are dictated by the physicochemical characteristics of lipid head groups and other molecule present on the membrane surface. Various hexagonal structures on the surface indicate this aspect. The hexagonal structures embedded in the membrane represent cholesterol. Aβ undergoes conformational changes based on the nature of the lipid which generates different conformational oligomer strains (denoted here as different shapes of yellow structures. Each strain can propagate their structures resulting in polymorphic fibrils.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Widespread interactions between Ab and lipids are significant in the etiology of Alzheimer disease.

Physiochemical character of lipids dictates their interactions with Ab, which generates many different aggregate structures.

The influence of lipids on Ab during the initial stages is critical in generating different oligomer strains.

Lipid-catalyzed generation of oligomer strains impart a variety of mechanisms to induce neuronal toxicity and phenotype differences in Alzheimer disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jucker M, Walker LC. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2013;501:45–51. doi: 10.1038/nature12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor CAGS, McGuire LC, Lu H, Croft JB. Deaths from Alzheimer’s Disease — United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:521–552. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6620a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83:4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selkoe DJ, Podlisny MB, Joachim CL, Vickers EA, Lee G, Fritz LC, Oltersdorf T. Beta-amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer disease occurs as 110- to 135-kilodalton membrane-associated proteins in neural and nonneural tissues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:7341–7345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shoji M, Golde TE, Ghiso J, Cheung TT, Estus S, Shaffer LM, Cai XD, McKay DM, Tintner R, Frangione B, et al. Production of the Alzheimer amyloid beta protein by normal proteolytic processing. Science (New York, NY) 1992;258:126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1439760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow VW, Mattson MP, Wong PC, Gleichmann M. An overview of APP processing enzymes and products. Neuromolecular medicine. 2010;12:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of A beta 42(43) and A beta 40 in senile plaques with end-specific A beta monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is A beta 42(43) Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto C, Castano EM. The conformation of Alzheimer’s beta peptide determines the rate of amyloid formation and its resistance to proteolysis. The Biochemical journal. 1996;314(Pt 2):701–707. doi: 10.1042/bj3140701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simmons LK, May PC, Tomaselli KJ, Rydel RE, Fuson KS, Brigham EF, Wright S, Lieberburg I, Becker GW, Brems DN, et al. Secondary structure of amyloid beta peptide correlates with neurotoxic activity in vitro. Molecular pharmacology. 1994;45:373–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilbich C, Kisters-Woike B, Reed J, Masters CL, Beyreuther K. Aggregation and secondary structure of synthetic amyloid beta A4 peptides of Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Biol. 1991;218:149–163. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90881-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saric A, Chebaro YC, Knowles TP, Frenkel D. Crucial role of nonspecific interactions in amyloid nucleation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:17869–17874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410159111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arosio P, Knowles TP, Linse S. On the lag phase in amyloid fibril formation. Physical chemistry chemical physics: PCCP. 2015;17:7606–7618. doi: 10.1039/c4cp05563b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linse B, Linse S. Monte Carlo simulations of protein amyloid formation reveal origin of sigmoidal aggregation kinetics. Molecular bioSystems. 2011;7:2296–2303. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00321b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garai K, Frieden C. Quantitative analysis of the time course of Abeta oligomerization and subsequent growth steps using tetramethylrhodamine-labeled Abeta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:3321–3326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222478110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen SI, Linse S, Luheshi LM, Hellstrand E, White DA, Rajah L, Otzen DE, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, Knowles TP. Proliferation of amyloid-beta42 aggregates occurs through a secondary nucleation mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:9758–9763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218402110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teplow DB. Structural and kinetic features of amyloid beta-protein fibrillogenesis. Amyloid: the international journal of experimental and clinical investigation: the official journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis. 1998;5:121–142. doi: 10.3109/13506129808995290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nichols MR, Moss MA, Reed DK, Lin WL, Mukhopadhyay R, Hoh JH, Rosenberry TL. Growth of beta-amyloid(1-40) protofibrils by monomer elongation and lateral association. Characterization of distinct products by light scattering and atomic force microscopy. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6115–6127. doi: 10.1021/bi015985r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jahn TR, Radford SE. The Yin and Yang of protein folding. The FEBS journal. 2005;272:5962–5970. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohnishi S, Takano K. Amyloid fibrils from the viewpoint of protein folding. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2004;61:511–524. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3264-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Necula M, Kayed R, Milton S, Glabe CG. Small molecule inhibitors of aggregation indicate that amyloid beta oligomerization and fibrillization pathways are independent and distinct. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10311–10324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gellermann GP, Byrnes H, Striebinger A, Ullrich K, Mueller R, Hillen H, Barghorn S. Abeta-globulomers are formed independently of the fibril pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bitan G, Kirkitadze MD, Lomakin A, Vollers SS, Benedek GB, Teplow DB. Amyloid beta -protein (Abeta) assembly: Abeta 40 and Abeta 42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:330–335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222681699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rangachari V, Moore BD, Reed DK, Bridges AW, Conboy E, Hartigan D, Rosenberry TL. Amyloid-β(1-42) Rapidly Forms Protofibrils and Oligomers by Distinct Pathways in Low Concentrations of Sodium Dodecylsulfate. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12451–12462. doi: 10.1021/bi701213s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kayed R, Pensalfini A, Margol L, Sokolov Y, Sarsoza F, Head E, Hall J, Glabe C. Annular protofibrils are a structurally and functionally distinct type of amyloid oligomer. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4230–4237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808591200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harper JD, Wong SS, Lieber CM, Lansbury PT., Jr Assembly of A beta amyloid protofibrils: an in vitro model for a possible early event in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8972–8980. doi: 10.1021/bi9904149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mantyh PW, Ghilardi JR, Rogers S, DeMaster E, Allen CJ, Stimson ER, Maggio JE. Aluminum, iron, and zinc ions promote aggregation of physiological concentrations of beta-amyloid peptide. Journal of neurochemistry. 1993;61:1171–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ha C, Ryu J, Park CB. Metal ions differentially influence the aggregation and deposition of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid on a solid template. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6118–6125. doi: 10.1021/bi7000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang SP, Bae DG, Kang HJ, Gwag BJ, Gho YS, Chae CB. Co-accumulation of vascular endothelial growth factor with beta-amyloid in the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2004;25:283–290. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshimoto M, Iwai A, Kang D, Otero DA, Xia Y, Saitoh T. NACP, the precursor protein of the non-amyloid beta/A4 protein (A beta) component of Alzheimer disease amyloid, binds A beta and stimulates A beta aggregation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:9141–9145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pawlikowska-Pawlega B, Kapral J, Gawron A, Stochmal A, Zuchowski J, Pecio L, Luchowski R, Grudzinski W, Gruszecki WI. Interaction of a quercetin derivative - lensoside Abeta with liposomal membranes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2017;1860:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho L, Ferruzzi MG, Janle EM, Wang J, Gong B, Chen TY, Lobo J, Cooper B, Wu QL, Talcott ST, Percival SS, Simon JE, Pasinetti GM. Identification of brain-targeted bioactive dietary quercetin-3-O-glucuronide as a novel intervention for Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2013;27:769–781. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-212118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu ML, Liu MJ, Shen YF, Ryu H, Kim HJ, Klupsch K, Downward J, Hong ST. Omi is a mammalian heat-shock protein that selectively binds and detoxifies oligomeric amyloid-beta. Journal of cell science. 2009;122:1917–1926. doi: 10.1242/jcs.042226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Randino R, Grimaldi M, Persico M, De Santis A, Cini E, Cabri W, Riva A, D’Errico G, Fattorusso C, D’Ursi AM, Rodriquez M. Investigating the Neuroprotective Effects of Turmeric Extract: Structural Interactions of beta-Amyloid Peptide with Single Curcuminoids. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38846. doi: 10.1038/srep38846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Planchard MS, Samel MA, Kumar A, Rangachari V. The natural product betulinic acid rapidly promotes amyloid-beta fibril formation at the expense of soluble oligomers. ACS chemical neuroscience. 2012;3:900–908. doi: 10.1021/cn300030a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh DM, Lomakin A, Benedek GB, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Amyloid beta-protein fibrillogenesis. Detection of a protofibrillar intermediate. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:22364–22372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward RV, Jennings KH, Jepras R, Neville W, Owen DE, Hawkins J, Christie G, Davis JB, George A, Karran EH, Howlett DR. Fractionation and characterization of oligomeric, protofibrillar and fibrillar forms of beta-amyloid peptide. The Biochemical journal. 2000;348(Pt 1):137–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguilar-Calvo P, Xiao X, Bett C, Erana H, Soldau K, Castilla J, Nilsson KP, Surewicz WK, Sigurdson CJ. Post-translational modifications in PrP expand the conformational diversity of prions in vivo. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43295. doi: 10.1038/srep43295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Natalello A, Prokorov VV, Tagliavini F, Morbin M, Forloni G, Beeg M, Manzoni C, Colombo L, Gobbi M, Salmona M, Doglia SM. Conformational plasticity of the Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker disease peptide as indicated by its multiple aggregation pathways. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:1349–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu JX, Qiang W, Yau WM, Schwieters CD, Meredith SC, Tycko R. Molecular structure of beta-amyloid fibrils in Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. Cell. 2013;154:1257–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiang W, Yau WM, Lu JX, Collinge J, Tycko R. Structural variation in amyloid-beta fibrils from Alzheimer’s disease clinical subtypes. Nature. 2017;541:217–221. doi: 10.1038/nature20814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Safar JG, Xiao X, Kabir ME, Chen S, Kim C, Haldiman T, Cohen Y, Chen W, Cohen ML, Surewicz WK. Structural determinants of phenotypic diversity and replication rate of human prions. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1004832. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasmussen J, Mahler J, Beschorner N, Kaeser SA, Hasler LM, Baumann F, Nystrom S, Portelius E, Blennow K, Lashley T, Fox NC, Sepulveda-Falla D, Glatzel M, Oblak AL, Ghetti B, Nilsson KPR, Hammarstrom P, Staufenbiel M, Walker LC, Jucker M. Amyloid polymorphisms constitute distinct clouds of conformational variants in different etiological subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease. 2017;114:13018–13023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1713215114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Condello C, Lemmin T, Stohr J, Nick M, Wu Y, Maxwell AM, Watts JC, Caro CD, Oehler A, Keene CD, Bird TD, van Duinen SG, Lannfelt L, Ingelsson M, Graff C, Giles K, DeGrado WF, Prusiner SB. Structural heterogeneity and intersubject variability of Abeta in familial and sporadic. Alzheimer’s disease. 2018;115:E782–e791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714966115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jucker M, Walker LC. Pathogenic protein seeding in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:532–540. doi: 10.1002/ana.22615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jucker MaW, Lary C. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2013;501:45–51. doi: 10.1038/nature12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kane MD, Lipinski WJ, Callahan MJ, Bian F, Durham RA, Schwarz RD, Roher AE, Walker LC. Evidence for seeding of beta -amyloid by intracerebral infusion of Alzheimer brain extracts in beta -amyloid precursor protein-transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3606–3611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03606.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langer F, Eisele YS, Fritschi SK, Staufenbiel M, Walker LC, Jucker M. Soluble Abeta seeds are potent inducers of cerebral beta-amyloid deposition. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14488–14495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3088-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, Kaeser S, Schaefer C, Kilger E, Neuenschwander A, Abramowski D, Frey P, Jaton AL, Vigouret JM, Paganetti P, Walsh DM, Mathews PM, Ghiso J, Staufenbiel M, Walker LC, Jucker M. Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science (New York, NY) 2006;313:1781–1784. doi: 10.1126/science.1131864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosen RF, Fritz JJ, Dooyema J, Cintron AF, Hamaguchi T, Lah JJ, LeVine H, 3rd, Jucker M, Walker LC. Exogenous seeding of cerebral beta-amyloid deposition in betaAPP-transgenic rats. J Neurochem. 2011;120:660–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stohr J, Watts JC, Mensinger ZL, Oehler A, Grillo SK, Dearmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Giles K. Purified and synthetic Alzheimer’s amyloid beta (Abeta) prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11025–11030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206555109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fritschi SK, Langer F, Kaeser SA, Maia LF, Portelius E, Pinotsi D, Kaminski CF, Winkler DT, Maetzler W, Keyvani K, Spitzer P, Wiltfang J, Kaminski Schierle GS, Zetterberg H, Staufenbiel M, Jucker M. Highly potent soluble amyloid-beta seeds in human Alzheimer brain but not cerebrospinal fluid. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2014;137:2909–2915. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kane MD, Lipinski WJ, Callahan MJ, Bian F, Durham RA, Schwarz RD, Roher AE, Walker LC. Evidence for seeding of β-amyloid by intracerebral infusion of Alzheimer brain extracts in β-amyloid precursor protein-transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3606–3611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03606.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bokvist M, Lindström F, Watts A, Gröbner G. Two Types of Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid (1–40) Peptide Membrane Interactions: Aggregation Preventing Transmembrane Anchoring Versus Accelerated Surface Fibril Formation. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;335:1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayashi H, Kimura N, Yamaguchi H, Hasegawa K, Yokoseki T, Shibata M, Yamamoto N, Michikawa M, Yoshikawa Y, Terao K, Matsuzaki K, Lemere CA, Selkoe DJ, Naiki H, Yanagisawa K. A seed for Alzheimer amyloid in the brain. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:4894–4902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0861-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kakio A, Nishimoto S, Yanagisawa K, Kozutsumi Y, Matsuzaki K. Interactions of amyloid beta-protein with various gangliosides in raft-like membranes: importance of GM1 ganglioside-bound form as an endogenous seed for Alzheimer amyloid. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7385–7390. doi: 10.1021/bi0255874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yip CM, McLaurin J. Amyloid-beta peptide assembly: a critical step in fibrillogenesis and membrane disruption. Biophys J. 2001;80:1359–1371. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terzi E, Holzemann G, Seelig J. Interaction of Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide(1-40) with lipid membranes. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14845–14852. doi: 10.1021/bi971843e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walter MF, Mason PE, Mason RP. Alzheimer’s disease amyloid beta peptide 25–35 inhibits lipid peroxidation as a result of its membrane interactions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:760–764. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pillot T, Goethals M, Vanloo B, Talussot C, Brasseur R, Vandekerckhove J, Rosseneu M, Lins L. Fusogenic properties of the C-terminal domain of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28757–28765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arispe N, Pollard HB, Rojas E. Zn2+ interaction with Alzheimer amyloid beta protein calcium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:1710–1715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lin H, Bhatia R, Lal R. Amyloid beta protein forms ion channels: implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2001;15:2433–2444. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0377com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ege C, Lee KY. Insertion of Alzheimer’s A beta 40 peptide into lipid monolayers. Biophysical journal. 2004;87:1732–1740. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.043265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chi EY, Ege C, Winans A, Majewski J, Wu G, Kjaer K, Lee KY. Lipid membrane templates the ordering and induces the fibrillogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptide. Proteins. 2008;72:1–24. doi: 10.1002/prot.21887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coles M, Bicknell W, Watson AA, Fairlie DP, Craik DJ. Solution structure of amyloid beta-peptide(1-40) in a water-micelle environment. Is the membrane-spanning domain where we think it is? Biochemistry. 1998;37:11064–11077. doi: 10.1021/bi972979f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jang H, Arce FT, Ramachandran S, Capone R, Azimova R, Kagan BL, Nussinov R, Lal R. Truncated beta-amyloid peptide channels provide an alternative mechanism for Alzheimer’s Disease and Down syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:6538–6543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914251107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee J. Amyloid beta Ion Channels in a Membrane Comprising Brain Total Lipid Extracts. 2017;8:1348–1357. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jang H, Teran Arce F, Ramachandran S, Capone R, Lal R, Nussinov R. Structural convergence among diverse, toxic beta-sheet ion channels. The journal of physical chemistry B. 2010;114:9445–9451. doi: 10.1021/jp104073k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jang H, Arce FT, Ramachandran S, Capone R, Lal R, Nussinov R. beta-Barrel topology of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid ion channels. J Mol Biol. 2010;404:917–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jang H, Zheng J, Nussinov R. Models of beta-amyloid ion channels in the membrane suggest that channel formation in the bilayer is a dynamic process. Biophysical journal. 2007;93:1938–1949. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jang H, Zheng J, Lal R, Nussinov R. New structures help the modeling of toxic amyloidbeta ion channels. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2008;33:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Strodel B, Lee JW, Whittleston CS, Wales DJ. Transmembrane structures for Alzheimer’s Abeta(1-42) oligomers. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:13300–13312. doi: 10.1021/ja103725c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quist A, Doudevski I, Lin H, Azimova R, Ng D, Frangione B, Kagan B, Ghiso J, Lal R. Amyloid ion channels: a common structural link for protein-misfolding disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:10427–10432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502066102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bode DC, Baker MD, Viles JH. Ion Channel Formation by Amyloid-beta42 Oligomers but Not Amyloid-beta40 in Cellular Membranes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2017;292:1404–1413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.762526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Korshavn KJ, Bhunia A, Lim MH, Ramamoorthy A. Amyloid-beta adopts a conserved, partially folded structure upon binding to zwitterionic lipid bilayers prior to amyloid formation. Chemical communications (Cambridge, England) 2016;52:882–885. doi: 10.1039/c5cc08634e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Williams TL, Serpell LC. Membrane and surface interactions of Alzheimer’s Abeta peptide--insights into the mechanism of cytotoxicity. The FEBS journal. 2011;278:3905–3917. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang Q, Zhao J, Yu X, Zhao C, Li L, Zheng J. Alzheimer Abeta(1-42) monomer adsorbed on the self-assembled monolayers. Langmuir: the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2010;26:12722–12732. doi: 10.1021/la1017906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao J, Wang Q, Liang G, Zheng J. Molecular dynamics simulations of low-ordered alzheimer beta-amyloid oligomers from dimer to hexamer on self-assembled monolayers. Langmuir: the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2011;27:14876–14887. doi: 10.1021/la2027913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ogawa M, Tsukuda M, Yamaguchi T, Ikeda K, Okada T, Yano Y, Hoshino M, Matsuzaki K. Ganglioside-mediated aggregation of amyloid beta-proteins (Abeta): comparison between Abeta-(1-42) and Abeta-(1-40) Journal of neurochemistry. 2011;116:851–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ikeda K, Matsuzaki K. Driving force of binding of amyloid beta-protein to lipid bilayers. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2008;370:525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chauhan A, Ray I, Chauhan VP. Interaction of amyloid beta-protein with anionic phospholipids: possible involvement of Lys28 and C-terminus aliphatic amino acids. Neurochemical research. 2000;25:423–429. doi: 10.1023/a:1007509608440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Drolle E, Hane F, Lee B, Leonenko Z. Atomic force microscopy to study molecular mechanisms of amyloid fibril formation and toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Drug metabolism reviews. 2014;46:207–223. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2014.882354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lindberg DJ, Wesen E, Bjorkeroth J, Rocha S, Esbjorner EK. Lipid membranes catalyse the fibril formation of the amyloid-beta (1-42) peptide through lipid-fibril interactions that reinforce secondary pathways. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2017;1859:1921–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wong PT, Schauerte JA, Wisser KC, Ding H, Lee EL, Steel DG, Gafni A. Amyloid-beta membrane binding and permeabilization are distinct processes influenced separately by membrane charge and fluidity. J Mol Biol. 2009;386:81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Davis CH, Berkowitz ML. Interaction between amyloid-beta (1-42) peptide and phospholipid bilayers: a molecular dynamics study. Biophysical journal. 2009;96:785–797. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Good TA, Murphy RM. Aggregation state-dependent binding of beta-amyloid peptide to protein and lipid components of rat cortical homogenates. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1995;207:209–215. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.John J, Kremer RMM. Kinetics of adsorption of β-amyloid peptide Aβ(1–40) to lipid bilayers. Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods. 2003;57:159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(03)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brown AM, Bevan DR. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Amyloid beta-Peptide (1-42): Tetramer Formation and Membrane Interactions. Biophysical journal. 2016;111:937–949. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shao H, Jao S, Ma K, Zagorski MG. Solution structures of micelle-bound amyloid beta-(1-40) and beta-(1-42) peptides of Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:755–773. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yamamoto N, Hasegawa K, Matsuzaki K, Naiki H, Yanagisawa K. Environment- and mutation-dependent aggregation behavior of Alzheimer amyloid beta-protein. Journal of neurochemistry. 2004;90:62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rangachari V, Reed DK, Moore BD, Rosenberry TL. Secondary structure and interfacial aggregation of amyloid-beta(1-40) on sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8639–8648. doi: 10.1021/bi060323t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bisaglia M, Trolio A, Bellanda M, Bergantino E, Bubacco L, Mammi S. Structure and topology of the non-amyloid-beta component fragment of human alpha-synuclein bound to micelles: implications for the aggregation process. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society. 2006;15:1408–1416. doi: 10.1110/ps.052048706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hagihara Y, Hong DP, Hoshino M, Enjyoji K, Kato H, Goto Y. Aggregation of beta(2)-glycoprotein I induced by sodium lauryl sulfate and lysophospholipids. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1020–1026. doi: 10.1021/bi015693q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nichols MR, Moss MA, Reed DK, Cratic-McDaniel S, Hoh JH, Rosenberry TL. Amyloid-beta protofibrils differ from amyloid-beta aggregates induced in dilute hexafluoroisopropanol in stability and morphology. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:2471–2480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nichols MR, Moss MA, Reed DK, Hoh JH, Rosenberry TL. Rapid assembly of amyloid-beta peptide at a liquid/liquid interface produces unstable beta-sheet fibers. Biochemistry. 2005;44:165–173. doi: 10.1021/bi048846t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mandal PK, Pettegrew JW. Alzheimer’s disease: soluble oligomeric Abeta(1-40) peptide in membrane mimic environment from solution NMR and circular dichroism studies. Neurochemical research. 2004;29:2267–2272. doi: 10.1007/s11064-004-7035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rangachari V, Moore BD, Reed DK, Sonoda LK, Bridges AW, Conboy E, Hartigan D, Rosenberry TL. Amyloid-beta(1-42) rapidly forms protofibrils and oligomers by distinct pathways in low concentrations of sodium dodecylsulfate. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12451–12462. doi: 10.1021/bi701213s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barghorn S, Nimmrich V, Striebinger A, Krantz C, Keller P, Janson B, Bahr M, Schmidt M, Bitner RS, Harlan J, Barlow E, Ebert U, Hillen H. Globular amyloid beta-peptide oligomer - a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of neurochemistry. 2005;95:834–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gellermann GP, Byrnes H, Striebinger A, Ullrich K, Mueller R, Hillen H, Barghorn S. Aβ-globulomers are formed independently of the fibril pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tay WM, Huang D, Rosenberry TL, Paravastu AK. The Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta(1-42) peptide forms off-pathway oligomers and fibrils that are distinguished structurally by intermolecular organization. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:2494–2508. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Huang D, Zimmerman MI, Martin PK, Nix AJ, Rosenberry TL, Paravastu AK. Antiparallel beta-Sheet Structure within the C-Terminal Region of 42-Residue Alzheimer’s Amyloid-beta Peptides When They Form 150-kDa Oligomers. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:2319–2328. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dahse K, Garvey M, Kovermann M, Vogel A, Balbach J, Fandrich M, Fahr A. DHPC strongly affects the structure and oligomerization propensity of Alzheimer’s Abeta(1-40) peptide. J Mol Biol. 2010;403:643–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kumar A, Bullard RL, Patel P, Paslay LC, Singh D, Bienkiewicz EA, Morgan SE, Rangachari V. Non-Esterified Fatty Acids Generate Distinct Low-Molecular Weight Amyloid-β (Aβ42) Oligomers along Pathway Different from Fibril Formation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kumar A, Paslay LC, Lyons D, Morgan SE, Correia JJ, Rangachari V. Specific Soluble Oligomers of Amyloid-β Peptide Undergo Replication and Form Non-fibrillar Aggregates in Interfacial Environments. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:21253–21264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fletcher TG, Keire DA. The interaction of beta-amyloid protein fragment (12–28) with lipid environments. Protein Sci. 1997;6:666–675. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mandal PK, McClure RJ, Pettegrew JW. Interactions of Abeta(1-40) with glycerophosphocholine and intact erythrocyte membranes: fluorescence and circular dichroism studies. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:2273–2279. doi: 10.1007/s11064-004-7036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhao H, Tuominen EK, Kinnunen PK. Formation of amyloid fibers triggered by phosphatidylserine-containing membranes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10302–10307. doi: 10.1021/bi049002c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kinoshita M, Kakimoto E, Terakawa MS, Lin Y, Ikenoue T, So M, Sugiki T, Ramamoorthy A, Goto Y, Lee YH. Model membrane size-dependent amyloidogenesis of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptides. Physical chemistry chemical physics: PCCP. 2017;19:16257–16266. doi: 10.1039/c6cp07774a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]