Abstract

Background

Improved breast cancer (BC) survival and evidence showing beneficial effects of internal mammary chain (IMC) irradiation underscore the importance of studying late cardiovascular effects of BC treatment.

Methods

We assessed cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence in 14,645 Dutch BC patients aged <62 years, treated during 1970–2009. Analyses included proportional hazards models and general population comparisons.

Results

CVD rate-ratio for left-versus-right breast irradiation without IMC was 1.11 (95% CI 0.93–1.32). Compared to right-sided breast irradiation only, IMC irradiation (interquartile range mean heart doses 9–17 Gy) was associated with increases in CVD rate overall, ischaemic heart disease (IHD), heart failure (HF) and valvular heart disease (hazard ratios (HRs): 1.6–2.4). IHD risk remained increased until at least 20 years after treatment. Anthracycline-based chemotherapy was associated with an increased HF rate (HR = 4.18, 95% CI 3.07–5.69), emerging <5 years and remaining increased at least 10–15 years after treatment. IMC irradiation combined with anthracycline-based chemotherapy was associated with substantially increased HF rate (HR = 9.23 95% CI 6.01–14.18), compared to neither IMC irradiation nor anthracycline-based chemotherapy.

Conclusions

Women treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy and IMC irradiation (in an older era) with considerable mean heart dose exposure have substantially increased incidence of several CVDs. Screening may be appropriate for some BC patient groups.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Epidemiology

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) survival has improved substantially in recent decades due to earlier diagnosis and treatment advances.1–5 At present, both radiation therapy (RT) and anthracycline-based chemotherapy are commonly used. They cure many women of their cancer but both treatments have been associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease (CVD).6,7 Radiation-related CVDs include ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and valvular heart disease (VHD), with evidence for dose-dependency.8–10 Previously, RT-related CVDs were thought not to emerge until 10 years after exposure.11–15 Recently, however, increased risks have been observed within 5 years of exposure.8,16 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy is associated with an increased, dose-dependent risk of cardiomyopathy (CMP) and heart failure (HF).17–19 However, the reported cumulative HF incidence after anthracycline-based chemotherapy varies.20–23

Since the 1970s, thousands of women in the Netherlands have been treated with internal mammary chain (IMC) irradiation using techniques that deliver substantial radiation doses to the heart. Since the 1990s, many women in the Netherlands have also received anthracycline-based chemotherapy. The absolute heart disease risks for women treated in the past are currently unclear, and it is not known which women might benefit from surveillance for heart disease.

Recent randomised trials have reported a BC-specific survival benefit after nodal irradiation, including IMC irradiation.24,25 This has re-opened the debate on the role of IMC irradiation in BC treatment.26 Women given IMC radiotherapy today may still receive around 8 Gy,27–30 but some cancer centres achieve much lower heart doses.28,29,31 Many of these women also receive anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Identifying interactions between RT and anthracycline-based chemotherapy or established cardiovascular risk factors8,11,32 is therefore relevant to women treated today.

Here we report the separate and combined effects of various radiation fields, chemotherapy types and established cardiovascular risk factors on the long-term risks of IHD, VHD and HF in a large cohort of BC patients aged <62 years at diagnosis.

Methods

Data collection procedures

Female BC patients (stages I–IIIA or ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS]) were selected from the hospital-based registries of the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam or the Erasmus MC - Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. All patients were diagnosed during 1970–2009 and before the age of 62 years. Data collection procedures have been published previously.11 In brief, patient and tumour characteristics, BC treatments (also locoregional recurrences and subsequent BCs) and CVD events were collected from registries and patient records. Patients were scored positive for hypertension, diabetes mellitus or hypercholesterolaemia if they received treatment for these conditions. Supplementary methods I shows detailed data collection procedures and patient eligibility criteria.

To complete information on CVD incidence, cardiovascular risk factors and causes of death, questionnaires were sent to general practitioners (GPs)i and, if applicable, cardiologists of all patients. (iIn the Netherlands, all residents are expected to have a primary care physician. Medical correspondence from attending physicians is sent to the primary care physician. Such records are preserved by the primary care physicians throughout a patient’s life and for at least 15 years after a patient’s death). Date of death was acquired through the population-based municipal personal records database.

In the current study, women treated with trastuzumab or taxanes (with or without anthracycline-based chemotherapy) for their primary BC (n = 979) were excluded, since follow-up was short and the numbers of events were too small to examine the effects of these treatments on CVD risks. The total analytic cohort comprised 14,645 patients.

Treatment

A detailed description of the treatment modalities used in our cohort from 1970 to 1986 has been published previously.11 During the 1970s, standard treatment for stage I–IIIa BCs consisted of mastectomy, with/without RT. In 1975, CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil) chemotherapy was introduced for premenopausal lymph node-positive patients. Breast-conserving surgery followed by whole breast irradiation was introduced in 1980. For women who underwent mastectomy, chest wall irradiation was indicated following incomplete resection or for extensive locoregional tumours. Regional nodal irradiation, including IMC irradiation, was used for women with positive axillary nodes and, in some cases, medial tumours. From the 1990s, anthracycline-based chemotherapy was used for most premenopausal, and later also for postmenopausal, lymph-node positive patients and for lymph-node negative patients with unfavourable tumour characteristics. Most common anthracycline dose was four times 60 mg/m2 (doxorubicin equivalent) during the study period. DCIS was treated with either wide local excision followed by whole-breast RT or with mastectomy.

In previous decades, IMC irradiation usually consisted of direct photon beams, sometimes combined with electron beams, giving a total target dose of 36–54 Gy in 12–26 fractions. In the most recent treatment period, IMC irradiation consisting of a combination of oblique photon and electron beams giving a total target dose of 50 Gy (25 fractions) resulting in lower exposure of the heart was introduced.33 Chest wall irradiation usually consisted of a direct electron beam giving a total target dose of 35–46 Gy (15–23 fractions). Whole breast irradiation usually consisted of tangential photon beams giving a total target dose of 44–52 Gy (22–26 fractions); most women also received a boost dose to the tumour bed.

Dosimetry

Dosimetry was performed to provide an indication of the typical level of cardiac exposure for women who received RT to different regions, according to laterality and IMC irradiation, during different time periods. Detailed information on the RT received was available for a sample of 683 women in the study cohort. Over 90% of these women were treated before the era of RT computed tomographic (CT) planning. Typical mean heart doses were estimated by reconstructing 44 different regimens on a “typical CT scan” (Supplementary methods II: Dosimetry). Dose distributions were generated for cobalt, electron and megavoltage beams using modern 3-dimensional CT treatment planning (Varian EclipseTM Treatment Planning System [TPS] version 10.0.39 [Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, USA]) and for orthovoltage fields using manual planning. A typical mean heart dose was allocated to each woman according to her regimen and total dose. Women were then categorised according to laterality and whether they received IMC irradiation. Within these categories, the typical doses were averaged. Given the large total number of women in the cohort, individual dosimetry was not undertaken and therefore no dose–response analyses have been performed.

Statistical analysis

BC treatments received throughout follow-up (including treatment for contralateral BCs and locoregional recurrences) were classified time-varyingly. Chemotherapy regimens were categorised as CMF-like or anthracycline-based regimens. Differences in the likely radiation exposure of the heart were accounted for by considering laterality and radiation fields (breast, chest wall, IMC).

Because collection of CVD incidence for patients treated during 1970–1986 was restricted to 10-year survivors,11 time-at-risk started 10 years after BC diagnosis for patients diagnosed ≤1986 and 1 year after BC diagnosis for patients diagnosed >1986. Time-at-risk ended at date of event of interest, death, emigration, distant metastasis or date of last information, whichever came first.

General population comparisons

The incidence rate of myocardial infarction (MI) and HF (comprising congestive HF and CMP) in the cohort was compared with age-, sex- and calendar period-specific CVD incidence rates for the Dutch population.34,35 No comparable reference rates were available for VHD and angina pectoris (AP). We calculated standardised incidence ratios (SIRs) and absolute excess risks and estimated 95% confidence intervals (CIs).36

Within-cohort comparisons

We assessed the association between treatments and CVD risk using proportional hazard models. A cardiovascular event was defined as a CVD diagnosis or death due to CVD. We estimated risks for any CVD (ICD-10 I20–52) and separately for IHD (MI and AP), VHD and HF. When analysing a specific CVD, the presence of any other CVD was treated as a time-dependent covariate. Additionally, age at BC, CVD history, risk factors at BC diagnosis (dichotomised into yes/no) and smoking were included in the models as main effects. Treatment-specific cumulative CVD incidence was estimated in patients above and below 50 years at BC diagnosis (to avoid mixing different age/treatment distributions), in the presence of death from causes other than CVD as a competing risk.37 Model assumptions were verified using residual-based methods. Because the proportional hazard assumption did not hold for the IHD rate after IMC and chest wall irradiation, analyses are presented separately for <10 and ≥10 years after treatment.

We evaluated whether the observed data were consistent with an additive or a multiplicative model for the joint effect of two risk factors A and B by likelihood ratio tests of γ = 0 in models HR(A,B) = 1 + β1A + β2B + γA×B and HR(A,B) = exp(α + β1A + β2B + γA×B).38 Analyses were performed using Stata/SE 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and EPICURE 1.8 (Hiro Soft International Inc, Seattle, WA). The study was approved by the review board of the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

Results

The median follow-up duration of our cohort (n = 14,645) was 14 years, with 3486 patients followed ≥20 years. Median age at BC diagnosis was 47 years. Eighty six percent of patients received RT, of whom 36% had IMC irradiation. One third of the patients received chemotherapy (58% anthracycline-based). Few patients were treated for cardiovascular risk factors at BC diagnosis (4.6%), but >20% were current or past smokers (Table 1). A statistically significant but small difference in CVD history was observed between left- and right-sided BC patients (left-sided: 3.6%, right-sided: 3.0%). Other characteristics, including treatments, did not differ significantly by laterality (data not shown). BC treatment (including the receipt of IMC irradiation and anthracycline-based chemotherapy) was not associated with socioeconomic status, cardiovascular history at BC diagnosis or cardiovascular risk factors. (Supplementary table 7)

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospital-based cohort of 14,645 breast cancer patients by year of breast cancer diagnosis

| Year of breast cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1970–1986 | 1987–1999 | 2000–2009 | |||||

| Characteristic | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Total no. of patients | 14,645 | 100 | 3571 | 100 | 6626 | 100 | 4448 | 100 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 47 (42–52) | 47 (42–53) | 46 (41–50) | 51 (45–56) | ||||

| <35 yearsa | 1010 | 6.9 | 236 | 6.6 | 562 | 8.5 | 212 | 4.8 |

| 35–40 years | 1568 | 10.7 | 433 | 12.1 | 813 | 12.3 | 322 | .2 |

| 40–49 years | 6586 | 45.0 | 1600 | 44.8 | 3486 | 52.6 | 1500 | 33.7 |

| 50–61 years | 5481 | 37.4 | 1302 | 36.5 | 1765 | 26.6 | 2414 | 54.3 |

| Stage | ||||||||

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | 929 | 6.3 | 40 | 1.1 | 318 | 4.8 | 571 | 12.8 |

| I | 4436 | 30.3 | 327 | 9.2 | 2168 | 32.7 | 1941 | 43.6 |

| II | 5251 | 35.9 | 433 | 12.1 | 3427 | 51.7 | 1391 | 31.3 |

| IIIa | 497 | 24.1 | 4 | 0.1 | 256 | 3.9 | 308 | 5.3 |

| Unknown | 3532 | 3.4 | 2767 | 77.5 | 457 | 6.9 | 237 | 6.9 |

| Type of surgery b | ||||||||

| Mastectomy | 8186 | 55.9 | 1139 | 31.9 | 4178 | 63.1 | 2869 | 64.5 |

| Wide local excision | 5127 | 35.0 | 2423 | 67.9 | 1639 | 24.7 | 1065 | 23.9 |

| Type of surgery unknown | 1332 | 9.1 | 9 | 0.3 | 809 | 12.2 | 514 | 11.6 |

| Radiation therapy and chemotherapy b | ||||||||

| None | 1663 | 11.4 | 439 | 12.3 | 578 | 8.7 | 646 | 14.5 |

| Radiation therapy alone | 8137 | 55.6 | 2513 | 70.4 | 3502 | 52.9 | 2122 | 47.7 |

| Chemotherapy alone | 406 | 2.8 | 19 | 0.5 | 216 | 3.3 | 171 | 3.8 |

| Radiation therapy and chemotherapy | 4439 | 30.3 | 600 | 16.8 | 2330 | 35.2 | 1509 | 33.9 |

| Radiation fields b | ||||||||

| No radiation therapy | 2069 | 14.2 | 458 | 12.8 | 794 | 12.0 | 817 | 18.4 |

| Breast, no IMC | 6301 | 43.0 | 621 | 17.4 | 3285 | 49.6 | 2395 | 53.8 |

| Typical mean heart dose left/right (Gy) | 4.8/0.6 Gy | 4.3/0.6 Gy | 4.8/0.7 Gy | 1.5/0.3 Gy | ||||

| Chest wall, no IMC | 796 | 5.4 | 337 | 9.4 | 382 | 5.8 | 77 | 1.7 |

| Typical mean heart dose left/right (Gy) | 5.8/2.8 Gy | 4.0/2.8 Gy | 6.3/2.8 Gy | 1.5/0.3 | ||||

| IMC, no chest wall or breast | 2269 | 15.5 | 1164 | 32.6 | 850 | 12.8 | 255 | 5.7 |

| Typical mean heart dose left/right (Gy) | 14.7/8.9 Gy | 12.2/8.9 Gy | 16.5/9.9 Gy | 16.1/9.4 Gy | ||||

| IMC and breast | 1429 | 9.8 | 475 | 13.3 | 679 | 10.3 | 275 | 6.2 |

| Typical mean heart dose left/right (Gy) | 16.6/13.4 Gy | 16.6/15.3 Gy | 21.8/13.4 Gy | 9.1/9.2 Gy | ||||

| IMC and chest wall | 806 | 5.5 | 430 | 12.0 | 226 | 3.4 | 150 | 3.4 |

| Typical mean heart dose left/right (Gy) | 16.1/10.1 Gy | 14.8/12.6 Gy | 16.4/10.5 Gy | 16.1/1.7 Gy | ||||

| Unknown | 975 | 6.7 | 86 | 2.4 | 410 | 6.2 | 479 | 10.8 |

| Chemotherapy regimen b | ||||||||

| No | 9800 | 66.9 | 2952 | 82.7 | 4080 | 61.6 | 2768 | 62.2 |

| CMF-like regimens | 2029 | 13.9 | 619 | 17.4 | 1422 | 21.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Anthracycline-based regimensc | 2816 | 19.2 | 0 | 0 | 1124 | 17.0 | 1680 | 37.8 |

| Endocrine therapy b | ||||||||

| No | 12,205 | 83.3 | 3503 | 98.1 | 6.043 | 91.2 | 2659 | 59.8 |

| Yes | 2440 | 16.7 | 68 | 1.9 | 583 | 8.8 | 1789 | 40.2 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors at breast cancer diagnosis d | ||||||||

| None known | 10,908 | 74.5 | 1875 | 52.5 | 5132 | 77.5 | 3901 | 87.7 |

| Hypertension, hypercholesterolemia or diabetes mellitus | 671 | 4.6 | 355 | 9.9 | 186 | 2.8 | 130 | 2.9 |

| Smokinge | 2966 | 20.3 | 1265 | 35.4 | 1326 | 20.0 | 375 | 8.4 |

| History of cardiovascular disease | 484 | 3.3 | 315 | 8.8 | 82 | 1.3 | 97 | 2.0 |

| Follow-up time (years) | ||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 14 (9–20) | 23 (17–28) | 15 (9–19) | 9 (6–11) | ||||

| 1–4 years | 1297 | 9.8 | 0 | 0 | 917 | 15.1 | 380 | 10.6 |

| 5–9 years | 2604 | 19.7 | 0 | 0 | 723 | 11.9 | 1881 | 52.6 |

| 10–19 years | 5816 | 44.0 | 1344 | 37.7 | 3154 | 52.0 | 1318 | 36.8 |

| 20–29 years | 2979 | 22.5 | 1702 | 47.7 | 1277 | 21.1 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥30 years | 523 | 4.0 | 523 | 14.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vital status | ||||||||

| Alive | 10,064 | 68.7 | 1889 | 52.9 | 4240 | 64.0 | 3935 | 88.5 |

| Deceased | 4580 | 31.3 | 1682 | 47.1 | 2385 | 36.0 | 513 | 11.5 |

IQR interquartile range, IMC internal mammary chain.

aMedian age for patients aged <35 years at diagnosis was 32 years, with an interquartile range of 30–34 years.

bMutually exclusive treatment groups, taking into account primary treatment only.

cIncluding either epirubicin or doxorubicin.

d335 patients had more than one of the mentioned cardiovascular risk factors at breast cancer diagnosis and these patients are listed more than once. The most frequent combinations involved current or previous smoking.

eSmoking defined as quit shortly before breast cancer diagnosis, smoker at breast cancer diagnosis or smoker during follow-up. 17.5 % of the cohort had never smoked. Smoking information was missing for 62.3% of the cohort

General population comparisons

Compared to the general population, our cohort had a higher MI rate (SIR = 1.4 95% CI 1.3–1.6), whereas the HF rate was not increased overall (SIR = 1.0 95% CI 0.9–1.1) (Table 2). While for HF the highest SIRs were seen for young ages at BC diagnosis, MI rates were increased only for older ages at diagnosis (Table 2). Subdividing the entire cohort by follow-up duration and treatment period, an increased HF rate was observed 1–9 years after treatment in patients treated ≥1987 (SIR = 1.4 95% CI 1.1–1.9 for 1987–1999 and 1.5 95% CI 1.0–2.0 for 2000–2009). In contrast, the increases in the MI rate were greatest in the longest follow-up intervals.

Table 2.

Comparison of myocardial infarction and heart failure rates with the general population

| Myocardial infarctiona | Heart failurea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | SIR | 95% CI | AER | Observed | SIR | 95% CI | AER | |

| Total | 394 | 1.4 | 1.3–1.6 | 8 | 396 | 1.0 | 0.9–1.1 | 0 |

| Age at breast cancer diagnosis (years) | ||||||||

| <35 | 5 | 0.9 | 0.3–2.1 | 0 | 12 | 2.7 | 1.4–4.7 | 7 |

| 35–40 | 17 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.8 | 1 | 20 | 1.4 | 0.9–2.2 | 4 |

| 40–49 | 180 | 1.5 | 1.3–1.7 | 8 | 179 | 1.1 | 1.0–1.3 | 3 |

| 50–61 | 192 | 1.4 | 1.2–1.6 | 12 | 185 | 0.8 | 0.7–1.0 | −8 |

| Calendar period of breast cancer diagnosis and follow-up interval | ||||||||

| 1970–1986 | ||||||||

| 10–19 years | 128 | 1.3 | 1.1–1.5 | 21 | 91 | 0.8 | 0.7–1.0 | −16 |

| 20+ years | 120 | 2.1 | 1.7–2.5 | 210 | 127 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.0 | −63 |

| 1987–1999 | ||||||||

| 1–9 years | 41 | 0.7 | 0.5–1.0 | -6 | 57 | 1.4 | 1.1–1.9 | 8 |

| 10–19 years | 54 | 1.7 | 1.3–2.2 | 15 | 64 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.4 | 3 |

| 20+ years | 8 | 1.7 | 0.7–3.4 | 24 | 9 | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 | −17 |

| 2000–2009 | ||||||||

| 1–9 years | 26 | 1.5 | 1.0–2.2 | 7 | 36 | 1.5 | 1.0–2.0 | 9 |

| 10+ years | 6 | 2.0 | 0.7–4.3 | 23 | 12 | 2.6 | 1.3–4.5 | 58 |

| Radiation therapy and chemotherapy | ||||||||

| None | 29 | 0.8 | 0.5–1.1 | −5 | 33 | 0.5 | 0.4–0.8 | −16 |

| Radiation therapy alone | 264 | 1.5 | 1.4–1.7 | 12 | 233 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.0 | −5 |

| Chemotherapy alone | 6 | 2.6 | 0.9–5.5 | 13 | 8 | 2.7 | 1.2–5.3 | 16 |

| Radiation therapy and chemotherapy | 75 | 1.7 | 1.4–2.2 | 9 | 122 | 2.1 | 1.7–2.5 | 16 |

| Radiation fields b | ||||||||

| Breast (no IMC) | 87 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.4 | 2 | 81 | 0.8 | 0.6–1.0 | −3 |

| Chest wall (no IMC) | 34 | 1.5 | 1.0–2.0 | 14 | 42 | 1.0 | 0.7–1.3 | −1 |

| IMC | 203 | 1.9 | 1.6–2.1 | 23 | 205 | 1.2 | 1.0–1.4 | 6 |

| Chemotherapy regimens | ||||||||

| CMF-like regimens | 59 | 1.7 | 1.3–2.2 | 11 | 44 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.4 | 0 |

| Anthracycline-based regimensc | 22 | 1.5 | 0.9–2.2 | 3 | 86 | 4.6 | 3.7–5.7 | 33 |

| Cardiovascular risk factor at BC diagnosis d | ||||||||

| None known | 342 | 1.3 | 1.2–1.5 | 6 | 347 | 1.0 | 0.9–1.1 | −1 |

| At least one | 52 | 2.3 | 1.7–3.0 | 42 | 49 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.8 | 17 |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Never | 110 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.3 | 3 | 115 | 0.8 | 0.6–0.9 | −10 |

| Currently or previous | 174 | 2.3 | 2.0–2.7 | 28 | 141 | 1.4 | 1.2–1.6 | 11 |

| Unknown | 110 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.2 | 0 | 140 | 0.9 | 0.8–1.1 | −1 |

SIR standardised incidence ratio, CI confidence interval, AER absolute excess risk, IMC internal mammary chain.

aExpected numbers were calculated using age-, sex- and calendar period-specific CVD incidence rates for the Dutch population. Myocardial infarction and heart failure incidence data from the Continuous Morbidity Registration Nijmegen of General Practices were used as reference rates for the years 1971–1999 and from the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research Primary Care Database from 2000 onwards. Myocardial infarction included diagnoses I21–22 International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision. Heart failure included both cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure; diagnoses I42 and I50 International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision. These were the only two cardiovascular diseases for which general population data were available. Just as in the general population registries, each individual patient in our cohort could have had a diagnosis of both myocardial infarction and heart failure.

bMutually exclusive treatment categories.

cIncluding either epirubicin or doxorubicin.

dHypertension, hypercholesterolaemia or diabetes mellitus

Among patients treated with neither RT nor chemotherapy, the MI rate was not increased (SIR = 0.8 95% CI 0.5–1.1) and the HF rate was decreased (SIR = 0.5 95% CI 0.4–0.8) compared with the general population. Increased MI rates were observed after RT (e.g. SIR = 1.5 95% CI 1.4–1.7 for patients treated with RT and without chemotherapy), while HF rates were increased after anthracycline-based chemotherapy (SIR = 4.6 95% CI 3.7–5.7).

Within-cohort comparisons

For women treated with RT, the lowest typical mean heart doses were for those who received right-sided breast irradiation without IMC (0.6 Gy, interquartile range (IQR) 0.3–0.7) (Table 1, Supplementary table 1). Compared to this group, women who received IMC irradiation (either left- or right-sided, average of mean heart doses for typical IMC irradiation 12.2 Gy, IQR 8.7–16.5) had significantly increased rates of all four cardiovascular outcomes: any CVD (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.56 95% CI 1.35–1.84), IHD (HR = 2.36 95% CI 1.74–3.22), VHD (HR = 1.63 95% CI 1.18–2.24) and HF (HR = 1.82 95% CI 1.27–2.63, based on inclusion of multiple CVDs per woman) (Summary model, Table 3). Increases were observed after both left- and right-sided IMC (Table 3) and with/without additional breast or chest wall radiation (Supplementary table 2). Increased rates of any CVD and of IHD were also seen after left chest wall irradiation (average of typical mean heart doses 5.8 Gy, IQR 3.8–5.3) when compared to right breast irradiation (HRs were 1.83 95% CI 1.39–2.40 and 2.57 95% CI 1.61–4.11, respectively). In the entire cohort, no significant increases were observed in women with left breast irradiation (average of mean heart doses 4.7 Gy, IQR 1.5–4.8) compared to those treated with right breast irradiation (HR for IHD 1.38 95% CI 0.96–1.99, Supplementary table 2); yet, for women treated at age ≤50 years an increased rate of IHD was observed (HR = 1.70 95% CI 1.03–2.80) (Supplementary table 3). Additional analyses considered just the first cardiovascular event and found the following (very similar) HRs for women who received IMC irradiation compared with women who received right-sided breast irradiation without IMC: any CVD (HR = 1.49 95% CI 1.25–1.77), IHD (HR = 2.51 95% CI 1.70–3.72), VHD (HR = 1.57 95% CI 1.02–2.44) and HF (HR = 1.71 95% CI 0.99–2.94) (Supplementary table 4).

Table 3.

Within-cohort comparison of cardiovascular disease rates after breast cancer by treatment

| Any cardiovascular event | Ischaemic heart disease ≥10 years after breast cancer treatmenta | Valvular heart disease | Heart failureb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/Nd | HR | (95% CI) | n/Nd | HR | (95% CI) | n/Nd | HR | (95% CI) | n/Nd | HR | (95% CI) | |

| Multivariable model c | ||||||||||||

| Radiation field f | ||||||||||||

| Breast, right-sided (no IMC) | 230/2562 | 1.00 | Ref. | 48/1684 | 1.00 | Ref. | 51/2519 | 1.00 | Ref. | 40/2520 | 1.00 | Ref. |

| Chest wall, right-sided (no IMCe) | 61/315 | 1.24 | 0.93–1.65 | 24/244 | 1.73 | 1.05–2.85 | 10/349 | 0.51 | 0.25–1.03 | 23/350 | 1.68 | 0.98–2.88 |

| IMC, right-sided (+/− breast/chest wall) | 344/1804 | 1.50 | 1.26–1.78 | 180/1478 | 2.54 | 1.84–3.52 | 97/1824 | 1.26 | 0.88–1.79 | 90/1824 | 1.78 | 1.21–2.61 |

| Breast, left-sided (no IMC) | 272/2761 | 1.11 | 0.93–1.32 | 70/1821 | 1.37 | 0.95–1.98 | 56/2797 | 1.00 | 0.69–1.47 | 41/2798 | 0.87 | 0.56–1.35 |

| Chest wall, left-sided (no IMCe) | 71/302 | 1.83 | 1.39–2.40 | 96/226 | 2.57 | 1.61–4.11 | 16/352 | 0.91 | 0.50–1.62 | 20/352 | 1.42 | 0.80–2.50 |

| IMC, left-sided (+/− breast/chest wall) | 413/1963 | 1.66 | 1.41–1.97 | 190/1621 | 2.20 | 1.59–3.04 | 162/2002 | 2.00 | 1.44–2.78 | 118/2002 | 1.94 | 1.33–2.82 |

| No radiation therapy | 221/1825 | 1.21 | 1.00–1.46 | 72/1222 | 1.50 | 1.04–2.17 | 44/1738 | 0.78 | 0.52–1.18 | 44/1741 | 1.22 | 0.79–1.89 |

| Chemotherapy f | ||||||||||||

| No chemotherapy | 1258/8238 | 1.00 | Ref. | 506/6112 | 1.00 | Ref. | 336/8296 | 1.00 | Ref. | 274/8301 | 1.00 | Ref. |

| CMF-like regimen | 240/1727 | 1.00 | 0.87–1.16 | 105/1363 | 1.07 | 0.85–1.33 | 72/1751 | 1.15 | 0.88–1.50 | 44/1749 | 0.89 | 0.64–1.24 |

| Anthracycline-based regimen | 193/2252 | 1.51 | 1.25–1.82 | 21/1107 | 1.00 | 0.61–1.64 | 43/2262 | 1.75 | 1.16–2.65 | 84/2263 | 4.32 | 3.07–6.07 |

| Endocrine therapy | ||||||||||||

| No endocrine therapy | 1518/10201 | 1.00 | Ref. | 605/7614 | 1.00 | Ref. | 406/10283 | 1.00 | Ref. | 345/10286 | 1.00 | Ref. |

| Endocrine therapy | 173/2016 | 0.97 | 0.80–1.17 | 27/968 | 0.85 | 0.55–1.29 | 45/2026 | 1.22 | 0.83–1.79 | 57/2027 | 0.93 | 0.65–1.31 |

| Summary model h | ||||||||||||

| Breast, right-sided (no IMC) | 230/2562 | 1.00 | Ref. | 48/1684 | 1.00 | Ref. | 51/2519 | 1.00 | Ref. | 40/2520 | 1.00 | Ref. |

| IMC (left- or right-sided, +/− breast/chest wall) | 757/3629 | 1.56 | 1.35–1.84 | 370/3099 | 2.36 | 1.74–3.22 | 259/3826 | 1.63 | 1.18–2.24 | 208/3826 | 1.82 | 1.27–2.63 |

| Joint effects of treatments f,g | ||||||||||||

| Breast RT (no IMC), no anthracyclines | 441/4475 | 1.00 | Ref. | 111/3102 | 1.00 | Ref. | 97/4423 | 1.00 | Ref. | 59/4312 | 1.00 | Ref. |

| IMC RT, no anthracyclines | 690/3113 | 1.54 | 1.35–1.75 | 361/2697 | 2.00 | 1.50–2.66 | 242/3159 | 1.74 | 1.35–2.25 | 165/2993 | 2.14 | 1.55–2.96 |

| Breast RT (no IMC), anthracyclines | 61/848 | 1.52 | 1.16–1.99 | 7/402 | 1.88 | 0.90–3.93 | 10/893 | 1.24 | 0.64–2.40 | 20/941 | 5.10 | 3.12–8.34 |

| IMC RT, anthracyclines | 67/654 | 2.09 | 1.62–2.69 | 9/402 | 2.32 | 1.19–4.55 | 17/667 | 2.86 | 1.76–4.65 | 31/683 | 9.23 | 6.01–14.18 |

| Test for departure from additivity/multiplicativity | p = 0.70/0.74 | p = 0.57/0.27 | p = 0.51/0.96 | p = 0.06/0.68 | ||||||||

n/N number of events/number at risk, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, IMC internal mammary chain, Ref. reference category.

The analyses shown in this table include all diagnoses of cardiovascular disease, e.g. if a patient was diagnosed with ischaemic heart disease and then later with valvular heart disease, then both are listed. Analyses considering just the first diagnosis of cardiovascular disease are in Supplementary Table 4.

aBecause the proportional hazard assumption did not hold for the ischaemic heart disease rate after internal mammary chain and chest wall irradiation, results are shown here for ≥10 years after breast cancer treatment. No increased ischaemic heart disease rates were seen in the period <10 years after treatment. These results are presented in Supplementary Table 5.

bHeart failure included both cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure; diagnoses I42 and I50 International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision.

cHazard ratios estimated using one multivariable model containing radiation fields (right breast, right-sided chest wall, right-sided internal mammary chain field, left breast, left-sided chest wall, left-sided internal mammary chain field, no radiation therapy, unknown radiation fields), chemotherapy (no chemotherapy, CMF-like regimen, anthracycline-based regimen), endocrine therapy (no, yes), age at breast cancer treatment (<40, 40–49, 50–61 years), cardiovascular risk factor at breast cancer diagnosis yes/no (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia or diabetes), smoking (ever, never or unknown) and other cardiovascular diseases (time-dependent). Hazard ratios for the covariates, estimates for patients with unknown radiation fields and estimates for patients irradiated to the internal mammary chain separately for patients additionally irradiated to the breast/chest wall are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

dAnalyses included all patients with at least 1 day of cardiovascular follow-up after start of time at risk (n = 12,355). Patients with a specific cardiovascular diagnosis before start of time at risk were excluded from analysis with that specific diagnosis as end point (n = 138 for any cardiovascular event [including also 27 diagnoses of arrhythmia and 3 of pericarditis], n = 50 for ischaemic heart disease, n = 18 for valvular heart disease and n = 36 for heart failure). Numbers at risk differs by end point due to time-dependency of the treatment variables.

eFor some women who were treated with direct electrons with the chest wall as the target, the internal mammary chain received a therapeutic dose.

fMutually exclusive treatment categories, taking into account primary treatment, as well as treatment for (loco)regional recurrences and second breast cancers.

gHazard ratios estimated using one multivariable model containing one variable for the joint effect of radiation therapy and anthracycline-based chemotherapy (breast irradiation without anthracycline-based chemotherapy, internal mammary chain irradiation without anthracycline-based chemotherapy, breast irradiation with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, internal mammary chain irradiation with anthracycline-based chemotherapy), age at breast cancer (<40, 40–50, 50–61 years), cardiovascular risk factor at breast cancer diagnosis yes/no (hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia or diabetes), smoking (ever, never or unknown) and other cardiovascular diseases (time-dependent). Patients not irradiated to either the breast or internal mammary chain were excluded from these analyses.

hHazard ratios estimated using one multivariable model containing radiation fields (right breast, right-sided chest wall, left breast, left-sided chest wall, internal mammary chain [left- or right-sided], no radiation therapy, unknown radiation fields), chemotherapy (no chemotherapy, CMF-like regimen, anthracycline-based regimen), endocrine therapy (no, yes), age at breast cancer treatment (<40, 40–49, 50–61 years), cardiovascular risk factor at breast cancer diagnosis yes/no (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia or diabetes), smoking (ever, never or unknown) and other cardiovascular diseases (time-dependent)

Women treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy had increased rates of VHD (HR = 1.75 95% CI 1.16–2.65) and HF (HR = 4.32 95% CI 3.07–6.07) compared to no chemotherapy (Table 3, based on inclusion of multiple CVDs per woman). When just the first cardiovascular diagnosis was considered, the increase in HF was slightly reduced (HR = 3.93 95% CI 2.49–6.22) (Supplementary table 4). When including VHD events diagnosed on the same day as IHD/HF, the anthracycline-based chemotherapy-associated risk of VHD was still increased (HR = 1.70 95% CI 1.09–2.65), but when excluding such VHD events the HR dropped to 1.11 (95% CI 0.62–2.00). Additional stratification by treatment period did not affect the estimates (results not shown). No increased CVD rates were observed comparing patients treated with endocrine therapy to no endocrine therapy.

The joint effects of IMC irradiation, anthracycline-based chemotherapy, cardiovascular risk factors at BC diagnosis and smoking were compatible with either an additive or a multiplicative relation for all CVDs (Supplementary table 6). For HF, however, the combined effect of IMC irradiation and anthracycline-based chemotherapy seemed more than additive (p = 0.06). A more than nine-fold increase was observed among patients treated with both IMC irradiation and anthracycline-based chemotherapy (HR = 9.23 95% CI 6.01–14.18), whereas the separate HRs were 2.14 (95% CI 1.55–2.96) and 5.10 (95% CI 3.12–8.34), respectively, all compared to either IMC or anthracycline-based chemotherapy (Table 3).

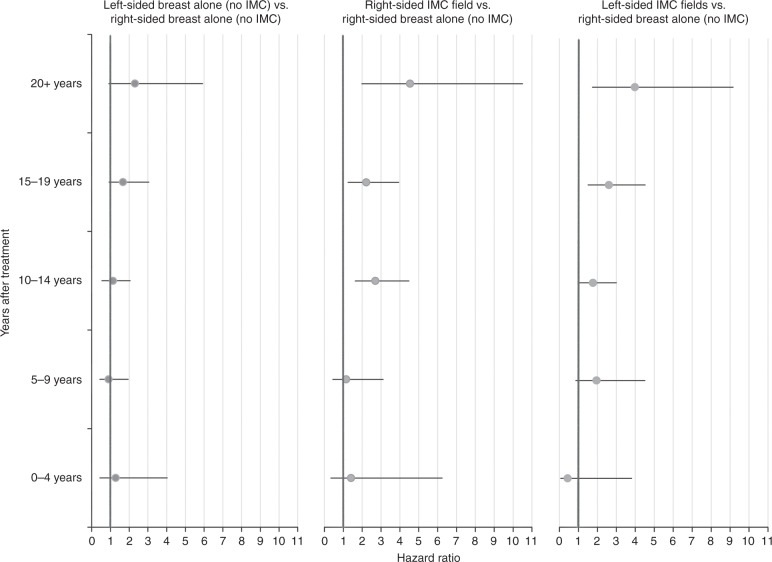

When analysing IHD rates by time since treatment, no significant increases were seen in the first 10 years (Fig. 1, Supplementary table 5). IMC irradiation during 1970–1986 or 1987–1999 was associated with increased IHD rates ≥10 years after treatment (Fig. 1, Table 4); the HR for 0–9 years after IMC irradiation compared to breast irradiation only during 1987–1999 was 1.32 (95% CI 0.74–2.37), while for 10+ years the HRs were 1.64 (95% CI 1.19–2.25) and 1.72 (95% CI 1.17–2.53) for 1970–1986 and 1987–1999, respectively. In the period 2000–2009, numbers were too small to detect or reject a risk increase for either 0–9 or ≥10 years after IMC irradiation (Table 4). HF rates after anthracycline-based chemotherapy were increased compared to no chemotherapy during the period 1–4 years after diagnosis (HR = 6.80 95% CI 2.75–16.82) and remained increased until at least 10–15 years after treatment (HR = 4.03 95% CI 2.70–6.00).

Fig. 1.

Within cohort comparison of ischemic heart disease rates by time since treatment and radiation therapy in patients diagnosed during 1970-1999. The analyses shown in this figure include all diagnoses of ischemic heart disease, e.g. including patients diagnosed with valvular heart disease or heart failure prior to ischemic heart disease. For women diagnosed with breast cancer during 1970-86, data on cardiovascular disease were available only for the period 10+years after treatment. IMC, internal mammary chain.Cox proportional hazard model including the following variables: radiation fields (right-), age at breast cancer treatment (<40, 40-49, 50-61 years), chemotherapy (none, CMF-like, anthracycline-based chemotherapy), cardiovascular risk factor at breast cancer diagnosis yes/no (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes), smoking (ever, never, or unknown), and other cardiovascular diseases diagnoses (time-dependent).In the period 2000-2009 follow-up duration was too short for reliable estimates (see Table 4)

Table 4.

Within-cohort comparison of ischaemic heart disease ratios for different radiation fields by time since treatment and treatment period

| Treatment period | Time since treatment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiation fielda | 0–9 years | 10–19 years | 20+ years | |||||||

| n/N | HR | (95% CI) | n/N | HR | (95% CI) | n/N | HR | (95% CI) | ||

| 1970–1986 | ||||||||||

| Breast only (no IMC) | 0/0 | — | 44/1162 | 1.00 | Ref. | 11/402 | 1.00 | Ref. | ||

| IMCb | 0/0 | — | 318/3899 | 1.35 | 0.93–1.96 | 144/1455 | 2.51 | 1.35–4.67 | ||

| 1987–1999 | ||||||||||

| Breast only (no IMC) | 37/3345 | 1.00 | Ref. | 66/3432 | 1.00 | Ref. | 10/784 | 1.00 | Ref. | |

| IMCb | 20/1524 | 1.32 | 0.74–2.37 | 48/1340 | 1.68 | 1.09–2.57 | 9/261 | 2.11 | 0.85–5.25 | |

| 2000-2009 | ||||||||||

| Breast only (no IMC) | 34/2,028 | 1.00 | Ref. | 8/686 | 1.00 | Ref. | 0/0 | — | ||

| IMCb | 5/544 | 0.62 | 0.23–1.62 | 4/290 | 0.90 | 0.26–3.05 | 0/0 | — | ||

n/N number of events/number at risk, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, IMC internal mammary chain, Ref. reference category.

aPatients were time-dependently categorised based on the treatment they received throughout follow-up into irradiation of the breast without internal mammary chain irradiation (either left or right breast), internal mammary chain irradiation (left- of right-sided) with or without radiation of additional fields and no/other radiation fields (estimates not shown).

bIrradiation of the left- or right-sided internal mammary chain, with or without additional irradiation of the breast or chest wall

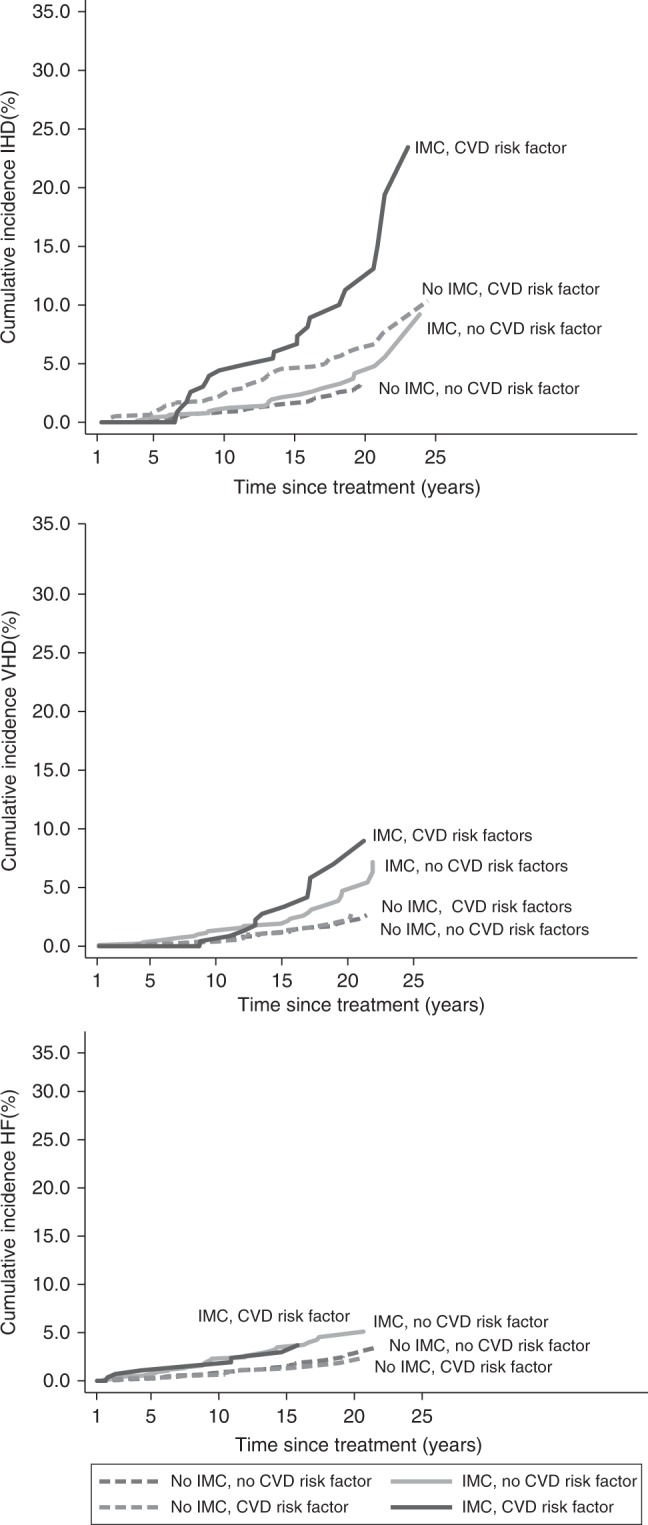

Among women diagnosed before age 50 years during 1987–1999, the cumulative incidence of IHD twenty years after BC treatment was 11.3% (95% CI 6.8–17.1) for those who received IMC irradiation and had a cardiovascular risk factor (including smoking) at diagnosis compared to 6.4% (95% CI 4.5–8.7) for those who had a cardiovascular risk factor but did not receive IMC irradiation (Fig. 2). For VHD and HF, the cumulative 20-year incidences were also considerably higher for women who received IMC radiation and had a cardiovascular risk factor compared with those who had a cardiovascular risk factor but no IMC radiation. Results for age 50+ years are in Supplementary Figure 1. Cumulative incidences of IHD, VHD and HF by anthracycline-based treatment and IMC irradiation for women aged ≤50 years are given in Supplementary Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative risk of cardiovascular diseases in patients diagnosed during 1987-1999 and aged 50 years or younger at breast cancer diagnosis, by internal mammary chain irradiation and cardiovascular disease risk factors (including smoking) at breast cancer diagnosis. IMC, internal mammary chain; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CHD, ischemic heart disease; VHD, valvular heart disease; HF, heart failure. The analyses of ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, and heart failure shown in this figure include all diagnoses of cardiovascular disease, e.g. if a patient was diagnosed with ischemic heart disease and then later with valvular heart disease then both events are counted. Patients with a specific cardiovascular diagnosis before start of time at risk were excluded from analysis with that specific diagnosis as endpoint (n=50 for ischemic heart disease, n=18 for valvular heart disease, and n=36 for heart failure)

Women treated more recently (1990–2006) had a lower cumulative MI risk than women treated in earlier years (1970–1989) (Supplementary Figure 3). In addition, the absolute increase in cumulative MI risk compared to the population-expected risk was notably smaller for those treated during 1990–2006 than for those treated before 1990. When compared with women receiving right breast RT only, the HR for all other RT regimens was 2.82-fold (95% CI 1.48–5.37) for the period 1980–1989 and 1.84 (95% CI 0.83–4.05) for the period 1990–2006 (10-year survivors only; pdifference = 0.41).

Discussion

Our study shows that, in women treated for BC in the Netherlands between 1970 and 2009, IMC irradiation was associated with an increased incidence of IHD, VHD and HF. Risk increases were seen not only after left-sided but also after right-sided IMC irradiation, and importantly, the proportional increase in the risk of IHD was greatest in the period >20 years after treatment. Anthracycline-based chemotherapy was associated with increased incidence of HF. The combination of IMC irradiation and anthracycline-based chemotherapy was associated with a nine-fold increased incidence of HF relative to patients who received only breast RT and no anthracycline-based chemotherapy.

Anthracycline-based chemotherapy (received by women in our cohort after 1990) was associated with increased HF incidence up to 15 years after treatment; there was insufficient follow-up to assess risk beyond this. Our estimate of the proportional increase in the rate (HR = 4.32) is somewhat higher than previously reported in population-based studies.21,39,40 A possible explanation is the young age of the women in our cohort, as we observed an even larger increases in patients treated ≤50 years (HR = 5.23 95% CI 3.41–8.01).

The increased VHD rate after anthracycline-based chemotherapy when multiple CVD diagnoses per woman are considered is a new finding in BC patients. Our detailed analysis, however, excluding VHD events diagnosed at the time of HF/IHD diagnosis suggests that the anthracycline-based chemotherapy-associated VHD risk in this cohort may be caused by anthracycline-based chemotherapy-related HF, rather than a direct effect of anthracycline-based chemotherapy. An anthracycline-related increase in the diagnosis of VHD as a first CVD event has previously been observed in Hodgkin lymphoma patients.41,42

In a recent case–control study, the risk of a major coronary event increased by 7.4%/Gy mean heart dose.8 Although not statistically significant, our HR of 1.38 for left breast (~5 Gy typical mean heart dose) versus right breast RT (~0.6 Gy typical mean heart dose) is consistent with these results. In our large, population-based cohort of early BC patients,43 we studied hospitalisation for CVD and also found an increased rate of IHD comparing left- versus right-sided breast irradiation (without IMC irradiation) (HR = 1.24 95% CI 1.01–1.52). These findings, together with the increased rate we observed in patients treated at age ≤50 years in the current study, suggest that left breast irradiation does slightly increase IHD risk. Also in line with Darby and colleagues’ results are our IHD HRs of 1.77–2.78 for women who received typical heart doses of ~9–15 Gy from IMC RT compared with women with right breast RT. The effect of cardiovascular risk factors on radiation-related cardiac risk in the two studies is also consistent. In both studies, cardiovascular risk factors prior to RT did not significantly increase relative risk of radiation-related CVD but did increase the absolute risk due to RT. Our study included patients up to the age of 61 years at BC diagnosis. Older patients generally have more cardiovascular risk factors. Hence, the absolute risks of treatment-related CVD may be higher in older patients. Additionally, the presence of cardiovascular risk factors might influence the onset of treatment-related CVD. Future studies should focus also on older BC patients and the onset of the increased CVD rates among these older patients.

Our results are relevant to a large number of BC survivors treated with older IMC regimens, who may remain at an elevated CVD risk for an extensive period. Follow-up in our study was too short to detect or reject an IHD risk increase associated with IMC irradiation during 2000–2009. Recent studies showing improved BC survival after IMC irradiation24,25,44 still have insufficient follow-up (≤10 years) to detect an increased CVD risk which, as we report, continues into the third decade after treatment. For women who receive BC treatment today, the predicted absolute risks of IMC RT are expected to be substantially lower than for the women in our study. This is partly because the IHD risk in the general population has decreased substantially since the 1970s (Supplemental Figure 3). A recent systematic review of heart dose estimates from BC RT during 2003–2013 showed that heart dose from IMC regimens varied according to technique and was typically ~8 Gy in left-sided RT27, which is lower than the average of ~13 Gy in our study. Modern radiotherapy techniques, including intensity-modulated radiotherapy and deep-inspirational breath hold, can deliver mean heart doses of <4 Gy even for IMC radiotherapy in left-sided tumours and their use is strongly recommended.

Our results suggest that the combined effects of radiation and anthracycline-based chemotherapy may be greater than their individual effects on the heart. This finding needs confirmation as in several countries guidelines recommend both IMC RT and anthracycline-based chemotherapy sequentially for women with poor prognostic features, such as nodal involvement.

Strengths of our study include data on RT fields and type of chemotherapy, GP- and cardiologist-reported CVD incidence and cardiovascular risk factors and long and near-complete follow-up. Surveillance bias in our study population is unlikely, as there are no recommendations concerning CVD screening in the nation-wide to BC follow-up guidelines in the Netherlands, which are adhered to closely.

A potential limitation that we have considered is whether the increased CVD risk associated with BC treatment might be due to a less favourable cardiovascular risk profile among women who received IMC radiation or anthracycline-based chemotherapy and this in turn might be associated with higher BC stage and lower socioeconomic status. However, in our relatively young BC cohort from two cancer centres, BC treatment was not associated with socioeconomic status, cardiovascular history at BC diagnosis or cardiovascular risk factors. Data on other risk factors for CVD, such as family history of CVD, body mass index and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, were, unfortunately, not collected. However, in the Netherlands, BC treatment guidelines do not recommend taking CVD risk factors into account and, accordingly, no differences in prevalence were observed between the treatment categories for the CVD risk factors that were collected. Therefore, missing information on other CVD risk factors is unlikely to have affected our estimates. Another potential limitation is the possibility of unreported events. Because, inherent to a retrospective study design, we rely on the registration of events in medical records, it is possible that some CVD events might have gone unreported. This might have caused our estimates to be slightly underestimated. Lastly, our study did not include patients treated with trastuzumab or taxanes, nor were we able to consider the different types of endocrine therapy. CVD rates after these modern systemic therapies should be evaluated in future studies.

In conclusion, anthracycline-based chemotherapy and irradiation using regimens with substantial mean heart doses (9–17 Gy) were associated with increased incidence of several types of CVDs. The predicted absolute risks of IMC RT are lower for women today, and for most women, the benefits will exceed the risks. However, the risks may be greater for some subgroups, e.g. women with left-sided BC who receive both IMC irradiation and anthracycline-based chemotherapy or who have cardiovascular risk factors. For BC survivors, our results are also relevant as subgroups may benefit from cardiac surveillance.45

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the collaboration of >5000 physicians throughout The Netherlands who provided follow-up data. Inquiries regarding access to the data presented in this paper should be addressed to Flora E. van Leeuwen, E-mail: f.v.leeuwen@nki.nl. This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant number NKI 2008-3994) and Pink Ribbon (grant 2012.WO39.C143) F.K.D., C.W.T. and S.C.D. received funding from Cancer Research UK (grant C8225/A21133), the British Heart Foundation Centre for Research Excellence, Oxford (grant RE/13/1/30181) as well as core funding from Cancer Research UK, the UK Medical Research Council and the British Heart Foundation to the Oxford University Clinical trial Service Unit (grant MC_U137686858).

Author contributions

The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (N.B.B., J.N.J., M.S., M.H., G.S.S., 27 E.J.T.R., N.S.R., B.M.P.A., F.E.v.L.); Erasmus MC – Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, The Netherlands 28 (M.J.H., C.M.S., M.H.A.B.); University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands 29 (J.A.G.); University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom (F.K.D., C.W.T., S.C.D.).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Berthe M. P. Aleman, Flora E. van Leeuwen.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41416-018-0159-x.

References

- 1.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:1707–1716. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Peto R, et al. Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;379:432–444. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) McGale P, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:2127–2135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60488-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romond EH, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaworski C, Mariani JA, Wheeler G, Kaye DM. Cardiac complications of thoracic irradiation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:2319–2328. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aleman BM, et al. Cardiovascular disease after cancer therapy. EJC Suppl. 2014;12:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcsup.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darby SC, et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:987–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cutter, D. J. et al. Risk of valvular heart disease after treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 107 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.van Nimwegen FA, et al. Radiation dose-response relationship for risk of coronary heart disease in survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:235–243. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooning MJ, et al. Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease in 10-year survivors of breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99:365–375. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooning MJ, et al. Cause-specific mortality in long-term survivors of breast cancer: a 25-year follow-up study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006;64:1081–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darby SC, McGale P, Taylor CW, Peto R. Long-term mortality from heart disease and lung cancer after radiotherapy for early breast cancer: prospective cohort study of about 300,000 women in US SEER cancer registries. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:557–565. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darby S, et al. Mortality from cardiovascular disease more than 10 years after radiotherapy for breast cancer: nationwide cohort study of 90 000 Swedish women. BMJ. 2003;326:256–257. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7383.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dess RT, et al. Ischemic cardiac events following treatment of the internal mammary nodal region using contemporary radiation planning techniques. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017;99:1146–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.06.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rehammar JC, et al. Risk of heart disease in relation to radiotherapy and chemotherapy with anthracyclines among 19,464 breast cancer patients in Denmark, 1977-2005. Radiother. Oncol. 2017;123:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gianni L, Salvatorelli E, Minotti G. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients: synergism with trastuzumab and taxanes. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2007;7:67–71. doi: 10.1007/s12012-007-0013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez EA, et al. Four-year follow-up of trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: Joint analysis of data from NCCTG N9831 and NSABP B-31. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:3366–3373. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romond EH, et al. Seven-year follow-up assessment of cardiac function in NSABP B-31, a randomized trial comparing doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel (ACP) with ACP plus trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:3792–3799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97:2869–2879. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowles EJ, et al. Risk of heart failure in breast cancer patients after anthracycline and trastuzumab treatment: a retrospective cohort study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1293–1305. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackey JR, et al. Adjuvant docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide in node-positive breast cancer: 10-year follow-up of the phase 3 randomised BCIRG 001 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:72–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70525-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganz PA, et al. Late cardiac effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer survivors treated on Southwest Oncology Group protocol s8897. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1223–1230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whelan TJ, et al. Regional nodal irradiation in early-stage breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:307–316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poortmans PM, et al. Internal mammary and medial supraclavicular irradiation in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:317–327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haffty BG, Whelan T, Poortmans PM. Radiation of the internal mammary nodes: is there a benefit? J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:297–299. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor CW, et al. Exposure of the heart in breast cancer radiation therapy: a systematic review of heart doses published during 2003 to 2013. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2015;93:845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.07.2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang JS, Chen J, Weinberg VK, Fowble B, Sethi RA. Evaluation of heart dose for left-sided breast cancer patients over an 11-year period spanning the transition from 2-dimensional to 3-dimensional planning. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2016;16:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong JC, et al. Radiation dose and cardiac risk in breast cancer treatment: an analysis of modern radiation therapy including community settings. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2017;8:e79–e86. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierce LJ, et al. Recent time trends and predictors of heart dose from breast radiation therapy in a large quality consortium of radiation oncology practices. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017;99:1154–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce LJ, et al. Recent time trends and predictors of heart dose from breast radiation therapy in a large quality consortium of radiation oncology practices. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017;99:1154–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris EE, et al. Late cardiac mortality and morbidity in early-stage breast cancer patients after breast-conservation treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:4100–4106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho BC, Hurkmans CW, Damen EM, Zijp LJ, Mijnheer BJ. Intensity modulated versus non-intensity modulated radiotherapy in the treatment of the left breast and upper internal mammary lymph node chain: a comparative planning study. Radiother. Oncol. 2002;62:127–136. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(01)00472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gijsen, R. & Poos, M. J. J. C. Coronaire Hartziekten: Omvang van het Probleem: Achtergronden en Details bij Cijfers uit Huisartsenregistraties. 2005 [cited 15 Feb 2005]. Available from http://www.rivm.nl/Onderwerpen/V/Volksgezondheid_Toekomst_Verkenning_VTV.

- 35.NIVEL NIfHSR. NIVEL primary care database 2014 [cited 25 Feb 2014]. Available from http://www.nivel.nl/en/dossier/nivel-primary-care-database.

- 36.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume II–The design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci. Publ. 1987;82:1–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat. Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::AID-SIM60>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothman, K. in Epidemiology, an Introduction 168–180 (Oxford University Press, New York, 2002).

- 39.Pinder MC, Duan Z, Goodwin JS, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Congestive heart failure in older women treated with adjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy for breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:3808–3815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thavendiranathan P, et al. Breast cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction in adult women treated in routine clinical practice: a population-based cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:2239–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Nimwegen FA, et al. Cardiovascular disease after Hodgkin lymphoma treatment: 40-year disease risk. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015;175:1007–1017. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aleman BM, et al. Late cardiotoxicity after treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2007;109:1878–1886. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boekel NB, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in a large, population-based cohort of breast cancer survivors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016;94:1061–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thorsen LB, et al. DBCG-IMN: a population-based cohort study on the effect of internal mammary node irradiation in early node-positive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:314–320. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.6456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armenian SH, et al. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:893–911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.