Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer and second leading cause of cancer death in men. It is frequently diagnosed via prostate biopsy following a rise in prostate specific antigen. While prostate cancer can metastasize, this most frequently occurs in bone and lymph nodes.1 Metastasis to the brain is rare and usually occurs in the setting of widespread metastasis. Here we report a case of a 77 year old male with isolated brain metastasis as the initial presentation of prostate adenocarcinoma in the setting of a normal prostate specific antigen.

Case presentation

A 77 year old man with a past medical history significant for symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia presented to the ED via ambulance after an unwitnessed fall in October 2017. Of note, he had undergone routine prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening since 1998 with his highest PSA being 1.3 in May 2017. He had a recent history of falls, memory deficits and weight loss and was being evaluated elsewhere for these symptoms with a known negative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head approximately 8 months prior to this presentation.

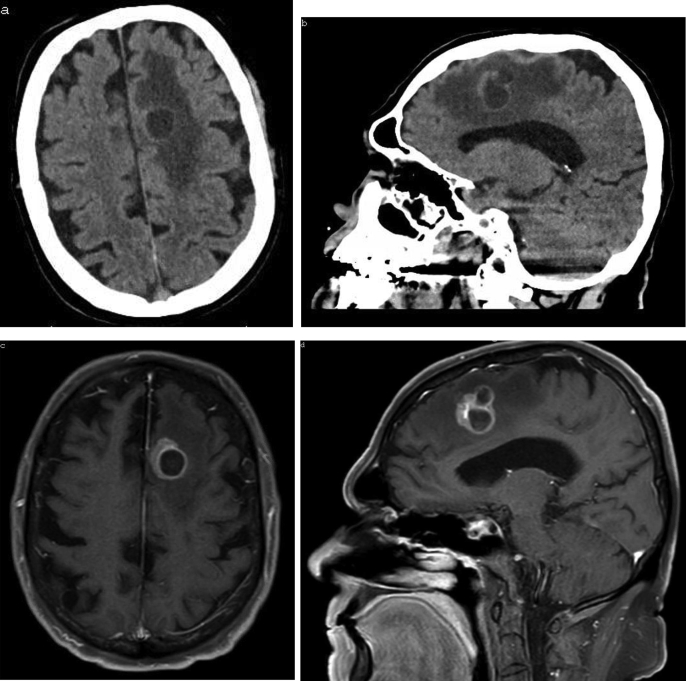

Upon further assessment a computed tomography (CT) of the head revealed a 3cm bilobed lesion in the left frontal lobe with surrounding edema, concerning for metastatic lesion or primary brain tumor (Fig. 1). Subsequent MRI of the brain confirmed a ring-enhancing left medial frontal lobe mass lesion with several daughter cavities and surrounding edema (Fig. 1). CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed an enlarged prostate with slight circumferential wall thickening of the urinary bladder, but otherwise was unremarkable for evidence of primary malignancy.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography (a, b) and magnetic resonance imaging (c–d) demonstrating intraparenchymal metastasis of prostate adenocarcinoma.

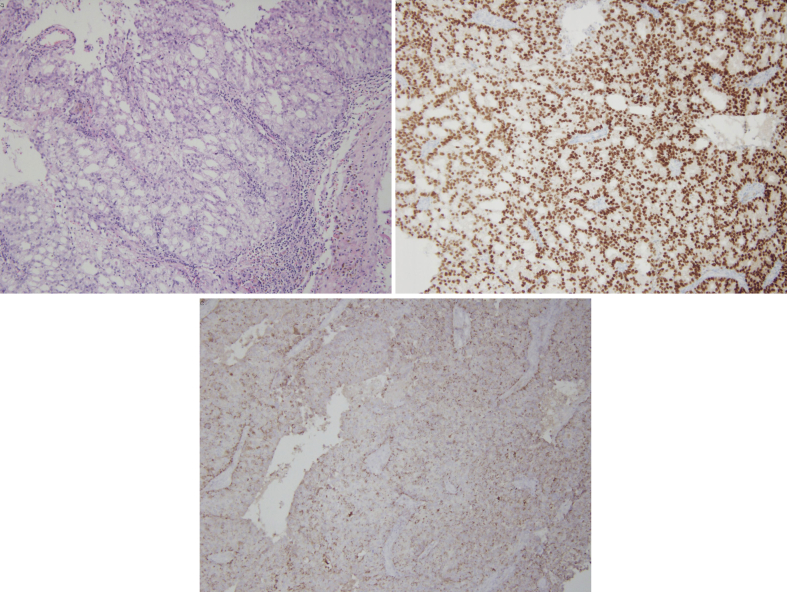

The patient underwent craniotomy with biopsy and resection of the mass lesion in October 2017, with post-operative MRI demonstrating resection of the mass without evidence of residual tumor. The resected specimen was nearly diffusely positive for prostate specific acid phosphatase (PSAP), focally positive for prostate specific antigen (PSA) and diffusely positive for NKX3.1, consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma (Fig. 2). Nuclear bone scan and MRI of the lumbar spine immediately following resection revealed no evidence of additional metastasis.

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs of resected left frontal brain tumor morphologically and immunohistochemically consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. (a) H&E stain (b) Diffusely positive for NKX3.1 (c) Nearly diffusely positive for PSAP.

The patient followed up in urology clinic in which digital examination revealed an enlarged prostate, approximately 40g with a discrete nodule at the left apex. PSA at follow-up visit was 0.9. Needle biopsy of the prostate was not done, rather the patient was assumed to have high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma that was not producing PSA. The patient subsequently began stereotactic radiation therapy of the tumor resection site and androgen deprivation therapy with Lupron. Since initiation of treatment, follow up imaging has demonstrated interval development of suspected bony metastasis despite an undetectable PSA.

Discussion

Metastasis occurs in approximately 18% of patients with prostate cancer, with the most frequent sites involving the skeleton (84%), distant lymph nodes (10.6%), liver (10.2%) and thorax (9.1%).1 Intraparenchymal metastasis of prostate cancer is infrequent, with Tremont-Lukats and colleagues updating and expanding upon the MD Anderson Cancer Center Experience to report an occurrence of 0.63% of all cases of prostate cancer and 1.6% of all cases of prostate cancer metastasis.2 A more recent assessment by Gandaglia and colleagues found similar incidence.1 Exceedingly more rare is isolated metastasis to the brain in the absence of alternative systemic disease. Of the 16,280 patients reviewed in the M.D. Anderson Experience, only 1 had an isolated intraparenchymal metastasis.2 Similarly, Gandaglia and colleagues cite that of all cases with a single site of metastasis, the brain comprises only 1% of these cases.1 Our own review of the literature revealed only 11 such case reports.

An even more unique feature of our case is that the patient presented with a normal prostate specific antigen. Review of the literature revealed only 6 cases of patients with isolated brain metastasis in the setting of a normal PSA, however in 5 of these cases the brain metastasis was a recurrence following prior treatment. The remaining case is similar to that presented here, however that patient was found to have small cell carcinoma of the prostate rather than adenocarcinoma as in our patient. Of note, while a majority of intraparenchymal metastases are adenocarcinoma in histology due to its >95% prevalence in overall cases of prostate cancer, small cell carcinoma is significantly more likely to produce brain metastasis.2,3

Resection of an isolated brain tumor with subsequent brain radiation therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrence compared to either alone and is the standard of care for solitary brain metastasis.4 This is consistent with the treatment recommendation put forth by others specific to prostate cancer metastasis to the brain.5 While whole brain radiation therapy was an option, this patient underwent stereotactic brain radiation therapy due to the low volume of disease. CNS treatment in this patient appears to have been successful thus far, without evidence of new or recurrent disease in the brain 7 months post-resection.

The unique presentation makes it difficult to assess prognosis for this patient. Unfortunately, prognosis is generally poor for patients with CNS metastasis of prostate cancer, with a median survival of 1 month upon diagnosis of CNS involvement and 3.5 months if stereotactic radiotherapy is used.3 As observed by Salvati and colleagues, this generally is not due to recurrence at the CNS site, rather death is usually a result of progression of additional metastatic disease.5 This too appears to be the case for our patient as surveillance imaging has already demonstrated likely skeletal progression of disease.

Conclusion

We present a case of prostate cancer diagnosed after resection of an isolated brain metastasis in the setting of a normal PSA. While rare, this case highlights much of what we still do not understand about prostate cancer; its presentation, early detection, progression, and variability.

Consent

Consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this report.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Declarations of interest

None.

Funding source

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eucr.2018.08.018.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Gandaglia G., Abdollah F., Schiffmann J. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74(2):210–216. doi: 10.1002/pros.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tremont-Lukats I.W., Bobustuc G., Lagos G.K., Lolas K., Kyritsis A.P., Puduvalli V.K. Brain metastasis from prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98(2):363–368. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCutcheon I.E., Eng D.Y., Logothetis C.J. Brain metastasis from prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86(11):2301–2311. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991201)86:11<2301::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardesty D.A., Nakaji P. The current and future treatment of brain metastases. Front Surg. 2016;3(May):1–7. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvati M., Frati A., Russo N. Brain metastasis from prostate cancer. Report of 13 cases and critical analysis of the literature. J Exp Clin Canc Res. 2005;24(2):203–207. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-22844449551&partnerID=40&md5=4f0b322e405c413769e63adb5af4c14e [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.