Short abstract

Background

Current data on critical illness during pregnancy are insufficient for evidence-based decision making. Core outcome sets are promoted to improve reporting of outcomes important to decision makers. We aim to develop a Core Outcome Set for research on critically ill obstetric patients (COSCO study).

Methods

We will perform a systematic review of studies on critical illness in pregnancy and focus groups or interviews with women who were critically ill while being pregnant. These data will inform an international Delphi survey where stakeholders will rank proposed outcomes. Selected outcomes will be brought forward to a consensus meeting where core outcomes will be defined. We will then complete a second consensus process to define measures for each core outcome.

Conclusion

The Core Outcome Set on Critically ill Obstetric patients study aims to develop a set of core outcomes to be part of all studies on critically ill obstetric patients. Implementation of this core outcome set will help improve future research efforts.

Trial registration: This study is registered on the COMET-initiative website (COS #916). This systematic review is registered on PROSPERO (CRD #42017071944).

Keywords: Intensive care medicine, maternal–fetal medicine, high-risk pregnancy, complications

Background

Altered maternal physiology, fetal implications of medical intervention and psychosocial issues make the management of the critically ill pregnant woman extremely challenging.1 Critical illness during the antepartum period poses challenges such as determining the safety of interventions and the maternal and fetal risks associated with continuing the pregnancy.2 Although critical illness during the post-partum period does not directly affect the newborn, it could affect mother–child bonding, breastfeeding and family dynamics.

Current data on critically ill pregnant women primarily comprises case reports and case series and are often insufficient for evidence-based decision making. There are several reasons for the lack of good quality observational and interventional evidence. First, critical illness requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission during pregnancy is a rare event estimated to have an incidence of 0.7–13.5 per 1000 deliveries and accounts for only 0.4% of all ICU admissions.3 Second, data and outcome reporting in existing studies are heterogeneous,3 making it difficult to compare outcomes between studies to inform evidence-based decision making. Third, critically ill pregnant women are excluded or under-represented in most completed or ongoing interventional trials involving ICU patients. Finally, study outcomes important to the mother, child and family members have not been elucidated. It is important that future research efforts tackle these issues by conducting multicentre studies with methodological rigour, focusing on issues considered important by pregnant women experiencing critical illness, and using standardized outcomes deemed essential by all stakeholders.

Core outcome sets (COSs) are increasingly being developed to identify outcomes important to decision makers, improve outcome reporting as well as standardize definitions and measures.4 COSs are described and promoted by the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Initiative, a group based in Liverpool and funded by the European Commission and the National Health Service National Institute for Health Research.5 This group defines COS as ‘the minimal outcomes that should be measured and reported in all clinical trials of a specific condition’.5 COSs have been endorsed by major organizations such as the International Forum for Acute Care Trialists (InFACT)6 and the Core Outcomes in Women’s and Newborn Health (CROWN) initiative.7 InFACT is an international forum promoting COS development for critical care trials,6 a field where COSs are still underdeveloped compared to others.8 The CROWN initiative aims to harmonize outcome reporting in women’s health research which includes COS development for conditions affecting pregnant women.7

With an overall aim of improving research in the field of critical illness in pregnancy, the COSCO study objective is to develop a COS for research on Critically ill Obstetric patients (during pregnancy and within six weeks’ post-partum). This paper describes our protocol for the development of this COS. Reporting of the protocol is important to ensure the eventual analysis and results are consistent with the investigators’ original intent, to make researchers in the field aware that the COS process is underway to avoid duplication, to foster collaboration and to provide a template for COS endeavours in related fields.

Methods

Overview

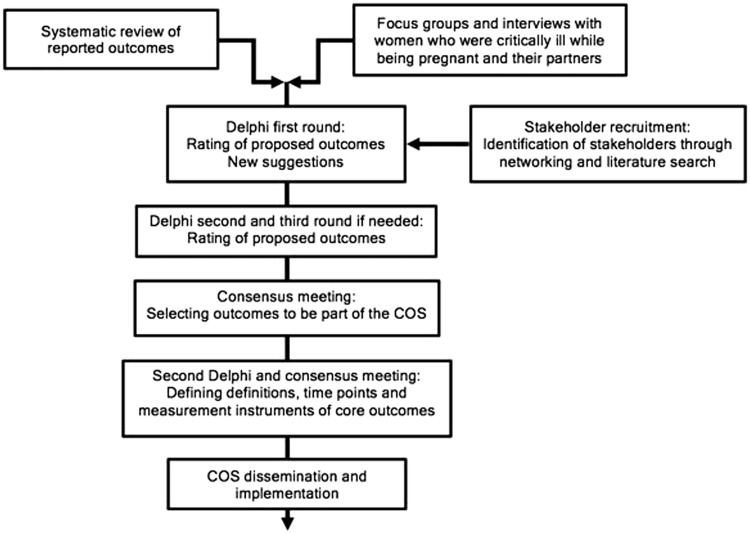

We will follow the recommendations of the COMET Initiative4 for development and the Core Outcome Set–STAndards for Reporting guidelines9 for reporting of this COS. The steps in the development of the COS are outlined in Figure 1. We will first identify outcomes on critical illness in pregnancy through the conduct of a systematic review, and focus groups and interviews with women who were critically ill while being pregnant and their partners. These outcomes will be used as the starting point to conduct a Delphi study involving multiple groups of stakeholders followed by consensus meetings to define core outcomes for inclusion in the COSs. We will then perform a second similar consensus process to define how the included outcomes should be measured.10 We expect the study to be completed within an 18-month timeline.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.COS: core outcome set.

Systematic review

We will perform a systematic review to identify outcomes reported in the literature (registered in PROSPERO CRD #42017071944).4,11 We will complete an electronic search with relevant keywords in the following databases from inception to November 2017: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Latin American database LILAC, ISI Web of Science and the WHO Global Index Medicus. We will include studies on women admitted in an ICU or high-dependency unit during pregnancy or post-partum period (≤6 weeks). Two reviewers will screen studies and extract reported outcomes and their measurement properties such as definitions, time points and Outcome Measurement Instruments (OMIs).

Focus groups and interviews

We will conduct focus groups and individual interviews with women who were critically ill while being pregnant and their partners to identify patient-important outcomes which can be different from those published in the literature.12–14 At least two groups of women will be interviewed including one group in a low or low-middle income country. We will classify countries using the 2017–2018 World Bank Country Classification.15 Each site conducting focus groups and interviews will obtain local research ethics board (REB) approval to recruit women and their partners, who will be identified by reviewing the previous years’ ICU admissions at participating sites and who will be contacted by postal letters.

Focus groups and interviews will be led by local researchers in countries representing various economic levels. These will be conducted and recorded with the help of experts in qualitative research methodology from each site according to a predefined script translated into the local language (online Appendix 1). The recorded interviews will be translated into English and analysed with the help of qualitative researchers. Definitions of outcomes and COSs using COMET plain language summaries will be provided.5 Patients and partners will be asked to discuss outcomes they consider relevant and their rationale. Discussions will last for 90 min or until no further outcomes are suggested. Discussions will be recorded, transcribed and translated into English if necessary.

We will analyse focus groups and interviews transcriptions as previously described.16,17 Outcomes described by women and partners will be compared to the systematic review results to make sure they represent unique outcomes excluding outcomes with similar meaning or wording. Lay language terms used by participants will be recorded.12 A final list of outcomes will be created using outcomes obtained through the systematic review and the focus group. These outcomes will be coded into domains using the new outcomes taxonomy and will inform the next step.18

Delphi study

Achievement of consensus between stakeholders is essential to COS development.19 We aim to include participants from multiple key stakeholder groups as a wide range of expertise is considered valuable.19 We will recruit participants from the five subgroups specified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Stakeholders subgroups included in the Delphi panel.

| Subgroup | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Clinicians | Clinicians with practical knowledge and at least five years’ experience in the fields of:Obstetrical critical careHigh-risk obstetrics/maternal–fetal medicineObstetrical medicineObstetrical anaesthesiaObstetrical and critical care nursingMidwiferyNeonatology/paediatrics |

| 2. Researchers | Primary or senior authors of peer-reviewed papers in the last 10 years in the field of obstetrical critical care identified through our systematic review |

| 3. Women and partners | Women who were critically ill while being pregnant and their partners |

| 4. Patient support groups | Representatives of patient support groups for pregnant women or critically ill patients (e.g. Preeclampsia Foundation,20 ICUsteps21) |

| 5. Journal editors | Editors from high impact peer-reviewed journals in the fields of obstetrics, obstetrical medicine and critical care |

To achieve consensus, we will use the Delphi technique.22 We will lead at least two survey rounds informed by group feedback where stakeholders will rank outcomes suggested until the defined consensus is reached. As mentioned earlier, the first round will be informed by outcomes identified by our systematic review and focus groups. We will attempt to minimize response bias and influence of power differentials to facilitate patients’ involvement by assuring anonymity, limiting group interaction and providing controlled feedback to participants.23–26

There is no universally accepted size for a Delphi study panel,4,10 but recently published COSs in the fields of critical care and obstetrics used panels between 75 and 150 participants.27–29 We will attempt to recruit between 15 and 30 representatives for subgroups 1–3 and 5–10 representatives for subgroups 4–5 for a total of 75 or more stakeholders.

Outcomes of critical illness during pregnancy differ between countries by income level.3 We will therefore attempt to include English-speaking stakeholders representing low and lower-middle income countries.

Stakeholder recruitment

We will use a multi-modal strategy to recruit Delphi participants. We will identify organizations (e.g. professional societies, trial groups, charities) relevant to stakeholder groups using personal networks and a web-based search. Primary contacts within each organization (e.g. Director, Administrator) will be emailed and asked to propose stakeholders or to disseminate our recruitment letter to their members.

Other methods for contacting stakeholders include advertisement at medical conferences and through professional societies for clinicians; personal invitation to the corresponding and senior authors of relevant studies identified through our systematic review. We will ask clinicians within our personal networks to identify former patients or caregivers that might be interested in an opportunity to participate in the study and to invite them to contact us. Finally, we will use social media (e.g. Twitter, Facebook), including sites of support groups and patient blogs to circulate study recruitment information.

We will use the COMET plain language summaries to describe the COS concept and the Delphi process.5,25 We will provide definitions in lay language terms for pregnancy, post-partum and critical illness, and describe each participant’s expected involvement and time investment. We will inform stakeholders that participation in the study will be indicative of consent to use anonymized data for future publications. We will collect data on participants’ home country, age and sex. In addition, clinicians and researchers will be asked to indicate their profession, speciality, current position and years of experience.

Procedure for the Delphi study

We will manage the Delphi process using the Delphi Manager online software (COMET Initiative, UK).5 The Delphi will comprise two rounds with a third round if additional outcomes suggested by participants in round one are retained after the second round. Each round will take place over six weeks and will start 2–4 weeks after the previous round to enable data synthesis. We will attempt to minimize attrition by sending biweekly reminders and making each round as concise as possible. Participants who have not participated in a round despite reminders will be excluded from future rounds.

First round

We will format all outcomes derived from our systematic review and focus groups in commonly used terms with explanations available in non-medical language. Participants of various stakeholders groups will be involved to develop outcome labels and explanations. We will group outcomes into domains for which the order will be randomized for each participant. We will pilot test the list with participants prior to providing the list to stakeholders.4

In first round, we will ask participants to rate the importance of each proposed outcome using the nine-point Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluations scale.30 Using this scale, scores 0–3 are considered of low importance, 4–6 important but not critical and 7–9 of critical importance. Participants will be asked to suggest any additional outcomes that they judge important for consideration for the COSs.

We will calculate the percentage of each score (1–9) based on the total number of responses and the median rating and interquartile range for every proposed outcome. We will calculate the median rating and interquartile range for each outcome for the following pooled participant category: (1) clinicians; (2) patients, partners and patient support group representatives and (3) researchers and journal editors. The feedback will be provided to stakeholders using a graphical summary of scores by pooled stakeholder category. Any new outcomes suggested by participants will be reviewed by the research team to ensure they represent new outcomes and will be worded appropriately for subsequent rounds including a non-medical language explanation.

Second and third rounds

On subsequent rounds, we will send the list of outcomes to participants to rescore in terms of importance. To reduce participant burden, we will retain outcomes which within each pooled subgroup at least 50% of participants scored as critically important and less than 15% scored not important during previous round. For each proposed outcome, we will provide stakeholders with their previous rating and a graphical summary of scores by stakeholder subgroups. Participants will be asked again to rate each outcome using the same 9-point scale.

Consensus definition

There is currently no universally accepted definition of consensus as to which scores on the 9-point scale indicate items that should be brought to a COS consensus meeting, but recent COSs have used similar definitions.19,31 We will therefore define consensus as an outcome which at least 70% of the panel members have rated as critically important and less than 15% have rated as not important.19 Outcomes fulfilling those criteria at the end of the final round will be moved forward to the consensus meeting.

Consensus meeting

We will conduct a virtual consensus meeting to discuss the outcomes brought forward from the Delphi and to vote on outcomes for inclusion in the COSs. We aim to involve 5–10 representatives from each of the stakeholder groups. If more stakeholders are interested than the number of desired attendees we will randomly select attendees within each group. If required we may complete a stand-alone briefing prior to the consensus meeting involving only patients, partners and representatives from patient support groups to allow discussions in lay language and facilitate their understanding. Although logistically more difficult than conducting face-to-face meetings, we have opted for virtual meetings in order to ensure involvement of participants (patients and caregivers) from around the world. Discussions will be moderated by an experienced facilitator and will follow a modified nominal group technique.32 We will involve information technology teams to ensure the smooth conduct of these meetings. After presentation of the outcomes brought to the consensus meetings, we will ask participants which outcomes they consider essential to the COSs and their rationale. We will then lead group discussions with the aim of ranking the top four to six core outcomes to be part of the COSs.

Outcome measurement

After having determined which outcomes should be part of the COSs we will define how to measure them. As suggested by the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN),10,33 we will collect data in our systematic review on measurement properties of reported outcomes. If outcomes not identified in our systematic review are selected as core outcomes we will perform an additional electronic search in the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases to identify their measurement properties. We will also search the COSMIN33 and COMET5 databases for data on OMI quality such as reliability, validity and feasibility. We will evaluate the measurement and psychometric properties of OMIs using the COSMIN checklist.33,34

We will invite stakeholders that completed the COS development to join a second consensus process. We will provide them data about the measurement and psychometric characteristics of OMIs. Using the same consensus methods as the COS development we will run a Delphi survey and consensus meetings to provide recommended measures for each core outcome.

Dissemination and implementation

We will work with researchers and journal editors to disseminate and implement the COSs. We aim to present the COSs at international conferences in the fields of critical care, obstetrics and obstetrical medicine. The COSs will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals in critical care and obstetrics. We will also work the COMET,5 InFACT6 and CROWN initiatives7 to publish the COSs in their databases.

Ethical considerations

We have obtained ethical approval from the Mount Sinai Hospital REB (Application 17-0238-E). Participation in the electronic Delphi survey will be considered indicative of consent. We will obtain written consent from focus groups, interviews and consensus meetings participants. Recruitment letters and consent forms will stress the voluntary nature of participation and anonymity.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for Development of a Core Outcome Set for research on critically ill obstetric patients: A study protocol by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Rohan D’Souza, Louise Rose and Stephen E Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine

Acknowledgements

Paula Williamson, COMET Initiative.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research is funded by the CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Women’s Lung Health.

Ethical approval

This study protocol was approved by the Mount Sinai Hospital REB (Application 17-0238-E).

Guarantor

SEL

Contributorship

All authors are acknowledged as contributing authors and approved manuscript submission.

References

- 1.Gaffney A. Critical care in pregnancy – is it different? Semin Perinatol 2014; 38: 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoyama K, Seaward PG, Lapinsky SE. Fetal outcome in the critically ill pregnant woman. Crit Care 2014; 18: 307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollock W, Rose L, Dennis CL. Pregnant and postpartum admissions to the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2010; 36: 1465–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials 2017; 18: 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.COMET Initiative. Core Outcome Measures for Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Initiative, http://www.comet-initiative.org/ (accessed 23 October 2017).

- 6.InFACT. International Forum for Acute Care Trialists (InFACT), http://www.infactglobal.org/ (2017, accessed 23 October 2017).

- 7.CROWN Initiative. The Core Outcomes in Women's and Newborn Health (CROWN) Initiative, http://www.crown-initiative.org/ (2017, accessed 23 October 2017).

- 8.Blackwood B, Marshall J, Rose L. Progress on core outcome sets for critical care research. Curr Opin Crit Care 2015; 21: 439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. Core outcome set–STAndards for reporting: the COS-STAR statement. PLoS Med 2016; 13: e1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prinsen CA, Vohra S, Rose MR, et al. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set” – a practical guideline. Trials 2016; 17: 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viau-Lapointe J, Twin S, Kfouri J, et al. Outcomes reported in studies on critically ill pregnant and postpartum women: a systematic review. PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews 2017. CRD42017071944. Available at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017071944.

- 12.Keeley T, Williamson P, Callery P, et al. The use of qualitative methods to inform Delphi surveys in core outcome set development. Trials 2016; 17: 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones JE, Jones LL, Keeley TJ, et al. A review of patient and carer participation and the use of qualitative research in the development of core outcome sets. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0172937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinton L, Locock L, Knight M. Maternal critical care: what can we learn from patient experience? A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e006676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The World Bank Group. World Bank Country and Lending Groups, https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2017-2018 (2018, accessed 1 March 2018).

- 16.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013; 15: 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dodd S, Clarke M, Becker L, et al. A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 96: 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials 2012; 13: 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preeclampsia Foundation. Helping save mothers and babies from illness and death due to preeclampsia, https://www.preeclampsia.org/ (accessed 23 October 2017).

- 21.ICUsteps. ICUsteps, http://www.icusteps.org/ (2017, accessed 23 October 2017).

- 22.Hasson F, Keeney S. Enhancing rigour in the Delphi technique research. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2011; 78: 1695–1704. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs 2003; 41: 376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval 2007; 12: 10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young B, Bagley H. Including patients in core outcome set development: issues to consider based on three workshops with around 100 international delegates. Res Involv Engagem 2016; 2: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirwan JR, Minnock P, Adebajo A, et al. Patient perspective: fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2007; 34: 1174–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egan AM, Galjaard S, Maresh MJA, et al. A core outcome set for studies evaluating the effectiveness of prepregnancy care for women with pregestational diabetes. Diabetologia 2017; 60: 1190–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al Wattar BH, Tamilselvan K, Khan R, et al. Development of a core outcome set for epilepsy in pregnancy (E-CORE): a national multi-stakeholder modified Delphi consensus study. BJOG 2017; 124: 661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, et al. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors: an International Modified Delphi Consensus Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196: 1122–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67: 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey N, Holmes CA. Nominal group technique: an effective method for obtaining group consensus. Int J Nurs Pract 2012; 18: 188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments, http://http//www.cosmin.nl (2017, accessed 23 October 2017).

- 34.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2010; 19: 539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for Development of a Core Outcome Set for research on critically ill obstetric patients: A study protocol by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Rohan D’Souza, Louise Rose and Stephen E Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine