Abstract

Objective:

To test the impact of employer matching of employee deposits on deposit contract participation rates and weight loss among obese employees.

Design:

36-week parallel design randomized controlled trial.

Setting:

Large employer in the United States.

Participants:

132 employees with a BMI between 30 and 50 kg/m2 who wanted to lose weight.

Interventions:

Participants were given the goal of losing 1 pound per week for 24 weeks and randomly assigned to a monthly weigh-in control group or daily automated feedback with monthly opportunities to deposit $1 to $3 per day. Deposits were either not matched (no match), matched 1:1 (1:1 match), or matched 2:1 (2:1 match) and provided back to participants at the end of the month for every day in that month that participant was at or below the goal weight for that day.

Main Outcome Measures:

Primary outcome was weight loss after 24 weeks. Secondary outcomes included deposit contract participation and weight loss after 36 weeks.

Results:

After 24 weeks, control arm participants gained an average of 1.0 pound (SD 7.6), compared to mean weight losses of 4.3 pounds (SD 8.9; P = .03) in the no match arm, 5.3 pounds (SD 10.1; P = .005) in the 1:1 match arm, and 2.3 pounds (SD 9.8; P = .29) in the 2:1 match arm. Rates of making at least 1 deposit among the 33 participants in the no match arm (18.2%), the 33 participants in the 1:1 match arm (36.4%), and the 33 participants in the 2:1 match arm (33.3%) were not significantly different (P = .22). 12 weeks after the deposit contract intervention ended, control arm participants gained an average of 2.1 pounds from baseline (SD 7.9), compared to mean weight losses of 5.1 pounds (SD 11.1; P = .008) in the no match arm, 3.6 pounds (SD 9.6; P = .02) in the 1:1 match arm, and 2.8 pounds (SD 10.1; P = .12) in the 2:1 match arm.

Conclusions:

Relatively few study participants assigned to deposit contract conditions took up opportunities to enter into deposit contracts designed to promote weight loss, and employer matching of deposits did not increase participation. Greater weight loss in deposit contract arms at 24 and 36 weeks may have been mediated by the automated feedback these participants received.

Trial Registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT01167634

INTRODUCTION

Most adults in the United States are overweight or obese.1 Two-thirds of large US employers now offer financial incentives to their employees2 to promote healthy behaviors such as weight loss.3,4 One financial incentive strategy that has gained considerable attention as a way to promote weight loss is the use of deposit or pre-commitment contracts.5–9 Deposit contracts are a device to help augment motivation in which people put some of their own money at risk that they stand to lose if they do not meet their goal. This approach leverages loss aversion,10 a powerful behavioral economic principle in which people are more affected by losses than an equivalent dollar gain.

While previous studies have demonstrated that deposit contracts can achieve weight loss,11,12 a major challenge to wider impact of these programs is getting high proportions of obese people to participate. This is of particular importance because motivation is only augmented through loss aversion in these programs if people actually make deposits. One way to increase participation in deposit contracts in workplace settings might be employer matching of employee deposits, but the degree to which higher rates of participation and weight loss can be achieved through such matching is unknown.

The objectives of this study were to test the degree to which differing levels of employer matching of employee deposits increase rates of participation in deposit contracts, characterize the corresponding amount of weight loss, and identify factors associated with non-participation in these programs.

METHODS

Design Overview

We conducted a 36-week parallel design randomized trial (24 intervention weeks plus 12 weeks of follow-up) at Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Jersey, a large employer in the United States, between May 24, 2011 and March 15, 2012. The 132 participants were randomly assigned to a control group or one of three deposit contract groups, all of which were given the same goal of losing one pound per week for 24 weeks. Weights were measured at baseline, four weeks, eight weeks, 12 weeks, 16 weeks, 20 weeks, 24 weeks, and 36 weeks using incentaHEALTH™ workplace scales that provided precision to 0.2 pounds. All participants had access to a secure website to track their progress and were asked to complete online questionnaires at baseline, 24 weeks, and 36 weeks. A subset of participants completed semi-structured telephone interviews focused on decisions about participation in deposit contracts. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania [INSERT NUMBER].

Setting and Participants

Eligible participants were employees of Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Jersey who were between ages 18 and 70, had a body mass index (BMI) of 30 to 50 kilograms per meter squared, and wanted to lose weight. The upper age was set at 70 because there may be less benefit from weight reduction after age 70 than at younger ages.13 Individuals with a BMI less than 30 were excluded to ensure all participants could safely lose the target weight of 24 pounds over the 24-week intervention. We chose an upper limit on BMI of 50 to minimize the influence of outliers on our primary outcome of weight loss. We also excluded those with conditions that would make participation infeasible (e.g., inability to consent or illiteracy) or potentially unsafe (e.g., current treatment for substance abuse, consumption of > 5 alcoholic drinks per day, addiction to prescription medications or street drugs, serious psychiatric diagnoses, myocardial infarction or stroke in the last 6 months, metastatic cancer, diabetes requiring treatment with medication other than metformin, currently pregnant or breastfeeding, or having a history of an eating disorder or unsafe weight loss behaviors such as laxative or diuretic use).

Individuals were recruited through workplace flyers, posters, email messages, and informational sessions. All participants were recruited in May and June 2011.

Randomization and Interventions

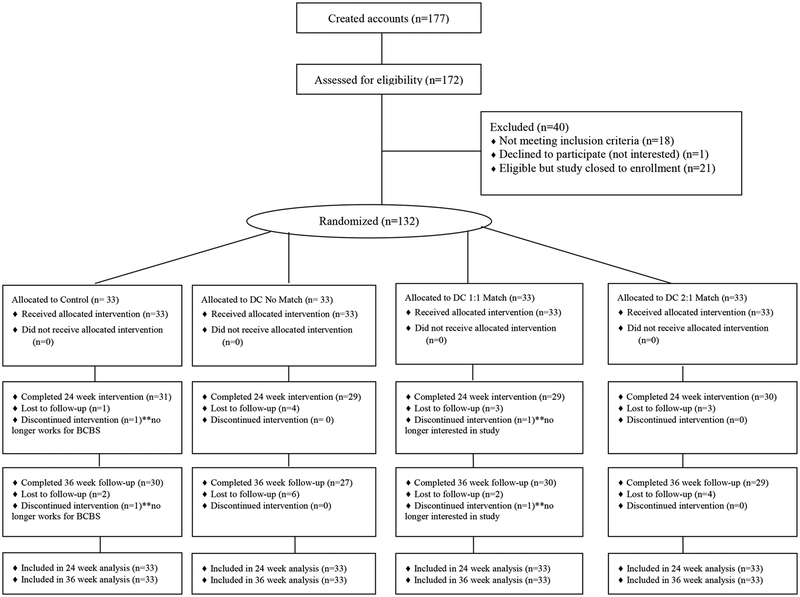

All 132 participants (Figure 1) provided their informed consent, were each given a goal to lose one pound per week over 24 weeks14, and were automatically assigned through a secure website to the 4 study arms using 1:1:1:1 central computerized randomization with variable block sizes of 4, 8, and 12 and stratification by BMI (30 to 40 or > 40 to 50). The allocation sequence was concealed from all research team members. Arm assignments were communicated to participants via an automated secure website message and email or text message. Neither participants nor the study coordinator could be blinded to condition assignment due to the nature of the interventions. Data analysts and all investigators were blinded to condition assignment until collection of all primary outcome data.

Figure 1.

Flow of Study Participants

Control arm participants were provided with a link to the Weight-control Information Network (http://win.niddk.nih.gov/) of the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease, and were both scheduled for and reminded via automated email or text message to attend monthly weigh-ins on the workplace scales. All weights collected were displayed graphically to each participant through a secure website. After each monthly weigh-in, an automated message was sent to participants that notified them of whether they met or did not meet their weight loss goal for that 4-week period.

Participants in each of the 3 deposit contract arms received the information that control arm participants received. In addition, at the start of each intervention month, participants in a deposit contract arm received an automated email or text invitation to go to the study website to make a deposit of their own money for the upcoming month. Through this website, participants could use their debit card or credit card to deposit between $1 per day and $3 per day for the next 28 days (i.e., $28 to $84 total in each month). For each day in that month that participants weighed in and were at or below their goal weight, the funds they had deposited for that day were returned at the end of the month as a reward, with a match corresponding to group assignment (described below).

The deposit contract interventions sought to leverage two common decision errors to make these rewards more effective than a standard economic incentive that would simply pay a reward of this amount. First, individuals tend to be overly optimistic about their prospects for success, which we expected to drive high rates of deposit contract participation.15 Second, when individuals’ own money is at risk they may be particularly driven to achieve a goal such as weight loss because they are highly motivated to avoid a financial loss.10

The 3 intervention arms featured different levels of deposit matching by the employer to test the degree to which an employer can use matching to increase rates of deposit contract participation and weight loss among employees. In the no match arm, money that participants deposited was refunded at the end of the month for every day in that month they weighed in and were at or below their goal weight. In the 1:1 match arm, money that participants deposited was matched 1:1 and refunded at the end of the month for every day in that month they weighed in and were at or below their goal weight. If, for example, a participant deposited $28 at the beginning of a month and met all of her daily weight loss goals, that participant received $56 (her original $28 plus the $28 in matching funds) at the end of that month. In the 2:1 match arm, money that participants deposited was matched 2:1 and refunded at the end of the month for every day in that month they weighed in and were at or below their goal weight.

Participants in the 3 deposit contract arms received a daily automated email or text message that stated whether they had been at or below their goal weight for that day, had been above their goal weight for that day, or had failed to weigh in. These messages had 2 goals. First, for participants who entered into deposit contracts, the messages provided timely feedback on their earnings and losses. Second, for participants who did not take up deposit contracts, the messages highlighted weight loss that could have resulted in earnings if they had deposited money, thus providing motivation to take up subsequent deposit contract opportunities in order to avert future regret.16,17

All participants were invited to measure their weight on the workplace scales as often as they desired. Further, all participant weights were depicted on a line graph that each participant could see by logging in to the study website.

We used 2 strategies to maximize retention of study participants, as retention rates in weight loss interventions are often low.18–20 First, the weight loss trajectory was revised every four weeks for study participants who failed to attain their weight loss goals. In these cases, the slope of the trajectory was increased such that the overall weight loss goal of 24 pounds remained the same but less successful participants would not have to immediately lose large amounts of weight to meet their monthly goals. Keeping the overall weight loss goal constant made the procedure fair for participants who maintained the ideal trajectory. However, the rate of weight loss was capped at 2 pounds per week when trajectories were revised to ensure a safe rate of weight loss. This approach was used in previous studies and resulted in participant loss to follow up rates of only 8.7%11 and 9.1%.12 Second, participants received $20 for completing each monthly weigh-in, $50 for completing the 24-week weigh-in, and $50 for completing one final weigh-in at 36 weeks (i.e., 12 weeks after the deposit contract interventions ended).

Participants were monitored for excessive weight loss that could pose a health risk, defined as losing more than 5 pounds in one week, 8 pounds in two weeks, or 12 pounds in four weeks. If an individual’s weight loss exceeded any of these thresholds, the study coordinator contacted the participant to inquire about their health status and any use of diuretics, diet pills, purging, or excessive exercise to lose weight with a plan to discuss with the study clinician any behaviors that warranted concern.

Semi-Structured Interviews

Following completion of the 24-week intervention, we conducted semi-structured interviews with participants in the 3 intervention arms to identify factors that influenced their participation in deposit contracts. We used purposive sampling to classify participants as having made no, some (1 to 3), or many (4 to 6) deposits. We then randomly identified participants in each of these 3 groups and asked them to participate in a brief telephone interview. The interviews consisted of mostly open-ended questions that asked participants to identify all of the reasons, and the most important reason, why they did and/or did not make deposits. We also asked participants what could have led them to make more deposits. Individuals were compensated $20 for participating in these interviews. In each group, we stopped conducting interviews when we reached thematic saturation.

Quantitative Data Analysis

The primary outcome was weight loss after 24 weeks. We hypothesized that participants in each deposit contract arm would have greater weight loss than control arm participants, and that greater amounts of deposit matching would lead to more weight loss than lesser amounts of deposit matching.

The main secondary outcome was participation in deposit contracts. We hypothesized that higher match rates would lead to a higher percentage of participants creating deposits, and a larger median amount of money committed, than among participants in arms with lesser amounts of deposit matching. Other secondary outcomes included weight loss at 36 weeks (i.e., 12 weeks after deposit contract opportunities ended) and changes in potential mediators of weight loss such as physical activity, eating behaviors, and participation in weight-related wellness programs from baseline to primary outcome measurement at 24 weeks. Physical activity was measured at baseline, 24 weeks, and 36 weeks through online administration of the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire21 and was operationalized as metabolic equivalent of task (MET)-minutes of physical activity during the last 7 days. Eating behaviors were measured at baseline, 24 weeks, and 36 weeks through online administration of the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire-R1822,23 and were operationalized as 0 to 100 scores in cognitive restraint, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating. Participation in weight-related wellness programs (defined as use of employer-sponsored weight loss resources or commercial weight loss programs) was measured at baseline, 24 weeks, and 36 weeks through an online questionnaire.

All analyses were intent-to-treat testing for differences between arms. We used t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (F-tests or Kruskal-Wallis test for 4 arms) for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Primary analyses used direct comparisons of outcomes by arm; we also assessed the impact of adjusting for demographic variables. We used multiple imputation to derive missing 24-week and 36-week weights using baseline variables as predictors, with 5 imputations per missing value.24 More details about the multiple imputation process are provided in the Appendix. To maintain the Type I error rate while testing the six hypotheses of primary interest, we used a Bonferroni correction to define an α of .0083 as our threshold for statistical significance.

We based our sample size on having adequate power to find differences in our primary outcome, weight loss at 24 weeks, between the intervention and control groups. We defined 11 pounds as a clinically significant amount of weight loss in this population.25,26 Making the assumption of a 11 pound standard deviation for weight loss12 and using an alpha of 0.0083, 33 subjects per arm provided 90% power to detect an 11 pound difference in weight loss between the control and no match groups, and a 5 pound incremental difference in weight loss between the no match, 1:1 and 2:1 match groups. This number of subjects per arm includes a 10% inflation factor to account for potential loss to follow-up. We used pounds instead of kilograms in all communication with study participants and in our power calculations since study participants were much more likely to be familiar with pounds than kilograms.

All hypothesis tests were 2-sided. We used SAS software Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) to analyze the data.

Qualitative Data Analysis

We coded the interview transcripts using qualitative methods. Three investigators independently reviewed a subset of transcripts using modified grounded theory to identify salient themes.27 These investigators then met to discuss the themes, refine them, and achieve consensus. There were 7 codes for reasons for making deposits, 19 codes for reasons for not making deposits, and 27 codes for factors that could have led to more deposits.

Once the coding scheme was established, two team members independently coded the transcripts in NVIVO software Version 9 (QSR International Pty Ltd., Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). First, the two raters independently coded the same 20% subset of the transcripts. The unweighted Cohen’s Kappa was calculated for each response and then averaged to provide a single index of inter-rater reliability. The resulting kappa indicated excellent agreement (k = .8225) between the two raters. The remaining interview transcripts were then divided evenly between the two raters and coded separately.

Role of the Funding Sources

This study was supported by grants from Horizon Healthcare Innovations, McKinsey & Company, and the National Institute on Aging. The authors had full responsibility in designing the study; collecting, analyzing, and interpreting the data; writing the manuscript; and deciding to submit the manuscript for publication.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

The sample of 132 subjects was predominantly female (87.1%) and African American (54.3%) or White (31.0%). The mean age was 43.9 and the mean baseline BMI was 37.3 kg/m2. Participants in the 1:1 match arm had higher mean uncontrolled eating scores (41.9) than participants in the control arm (mean 30.3, P = 0.005). There were no other significant differences in baseline characteristics of participants in each arm (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample

| N (%) or Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Control (n=33) |

No match (n=33) |

1:1 match (n=33) |

2:1 match (n=33) |

| Female sex | 27 (81.8) | 32 (97.0) | 30 (90.9) | 26 (78.8) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 45.9 (9.0) | 43.5 (9.6) | 44.3 (11.5) | 42.0 (9.6) |

| Initial weight measurements, mean (SD) | ||||

| Weight in pounds, mean (SD) | 220.3 (34.4) | 221.6 (36.6) | 213.6 (40.3) | 238.1 (49.0) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 36.6 (4.4) | 38.2 (4.9) | 35.9 (4.9) | 38.5 (5.6) |

| Racea | ||||

| White | 10 (30.3) | 8 (25.8) | 12 (37.5) | 10 (30.3) |

| African American | 18 (54.5) | 19 (61.3) | 15 (46.9) | 18 (54.5) |

| Other | 4 (12.1) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.5) | 3 (9.1) |

| Two or more races | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.1) |

| Hispanic or Latinob | 3 (9.1) | 4 (12.1) | 5 (15.6) | 5 (15.2) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than college | 7 (21.2) | 3 (9.1) | 3 (9.1) | 1 (3.0) |

| Some college | 8 (24.2) | 14 (42.4) | 15 (45.5) | 17 (51.5) |

| College graduate | 10 (30.3) | 11 (33.3) | 13 (39.4) | 12 (36.4) |

| Post-college degree | 8 (24.2) | 5 (15.2) | 2 (6.1) | 3 (9.1) |

| Household incomec | ||||

| < $50,000 | 3 (9.4) | 3 (9.4) | 6 (18.2) | 6 (18.8) |

| $50,000 to <$100,000 | 15 (46.9) | 18 (56.3) | 18 (54.5) | 18 (56.3) |

| ≥ $100,000 | 14 (43.8) | 11 (34.4) | 9 (27.3) | 8 (25.0) |

| Cognitive restraint, mean (SD)d | 52.5(17.0) | 52.5(15.4) | 47.0(19.6) | 46.3(17.0) |

| Uncontrolled eating, mean (SD)d | 30.3(16.6) | 35.5(14.4) | 41.9(19.9) | 33.7(13.8) |

| Emotional eating, mean (SD)d | 45.1(26.9) | 48.3(23.7) | 50.8(27.1) | 46.8(22.7) |

| MET minutes per week, mean (SD)e | 3290 (2892) | 2143 (2036) | 2578 (2601) | 2288 (2425) |

| Participation in any weight related programf | 24/30(80.0) | 26/30(86.7) | 23/29(79.3) | 23/27(85.2) |

BMI = body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; MET = metabolic equivalent of task.

Self-identified by participants on baseline questionnaire. 3 participants (2 in the no match arm and 1 in the 1:1 match arm) did not complete the race questions.

Self-identified by participants on the baseline questionnaire. 1 participant in the 1:1 match arm did not complete the ethnicity questions.

3 participants did not complete the household income question on the baseline questionnaire: 1 in the control arm, 1 in the no match arm, and 1 in the 2:1 match arm.

Measured on a 0 to 100 scale. Higher scores signify more of that behavior.

MET minutes are a quantification of physical activity that reflect both intensity (in METs) and duration (in minutes) of activity.

Defined as onsite employer-sponsored weight loss resources or commercial weight loss programs. 16 participants did not complete this part of the baseline questionnaire: 3 in the control arm, 3 in the no match arm, 4 in the 1:1 match arm, and 6 in the 2:1 match arm.

Deposit Contract Participation

Deposit contract participation rates by arm are shown in Table 2. In the first month, 5 of the 33 (15.2%) participants in the no match arm, 8 of the 33 1:1 match participants (24.2%), and 9 of the 33 2:1 match participants (27.3%) made a deposit. There were no significant differences in this initial participation rate across arms. During the full 24-week intervention, 6 of the 33 (18.2%) participants in the no match arm, 12 of the 33 1:1 match participants (36.4%), and 11 of the 33 2:1 match participants (33.3%) made at least one monthly deposit. There were no significant differences in the overall participation rate across arms. Among participants who made at least one deposit, there were no significant differences by arm in the median sizes of monthly deposits or the median total amounts deposited.

Table 2.

Deposit Contract Participation

| Measure | No match (n=33) |

1:1 match (n=33) |

2:1 match (n=33) |

Total (n=99) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deposit in first 4 weeks | ||||

| N (%) | 5 (15.2) | 8 (24.2) | 9 (27.3) | 22 (22.2) |

| 95% CI | 2.9, 27.4 | 9.6, 38.9 | 12.1, 42.5 | 14.0, 30.4 |

| Median number of deposits (IQR) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) | 0 (2) | 0 (1) |

| ≥ 1 deposit during 24 week intervention | ||||

| N (%) | 6 (18.2) | 12 (36.4) | 11 (33.3) | 29 (29.3) |

| 95% CI | 5.0, 31.3 | 20.0, 52.8 | 17.3, 49.4 | 20.3, 38.3 |

| Characteristics of deposits [median (IQR)]a | ||||

| Number of depositsb | 2.5 (2) | 3 (2.5) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Dollars per deposit (IQR)c | 28 (0) | 63 (56) | 37 (56) | 37 (51) |

| Total dollars deposited (IQR)d | 70 (56) | 210 (182) | 112 (280) | 112 (196) |

| Net dollars earned or lost (IQR) | −21 (36) | −10 (193) | 90 (320) | −8 (175) |

IQR = interquartile range

Among participants who made one or more deposits during the 24 week intervention.

Participants could make up to 6 deposits during the 24-week intervention.

Participants could deposit between $28 and $84 (i.e., $1to $3 per day) every 28 days during the 24 week intervention.

Amounts reflect participant money only and do not include any applicable matching funds. Participants could have deposited up to a total of $504.

24 Week Outcomes

After 24 weeks (Table 3), 1:1 match participants lost significantly more weight (mean 5.3 pounds, SD 10.1) than participants in the control group, who gained an average of 1.0 pounds (SD 7.6; P = .005). Participants in the no match arm lost a comparable amount of weight (mean 4.3 pounds, SD 8.9) but this was not significantly different than the control group (P = .03) after the Bonferroni correction. 2:1 match participants lost an average of 2.3 pounds (SD 9.8; P = 0.29 compared to control).

Table 3.

24-Week Weight Loss by Arma

| Measure | Control (n=33) |

No match (n=33) |

1:1 match (n=33) |

2:1 match (n=33) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss, poundsb | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −1.0 (7.6) | 4.3 (8.9) | 5.3 (10.1)c | 2.3 (9.8) |

| 95% CI | −4.3, 2.3 | 0.8, 7.9 | 1.9, 8.7 | −0.8, 5.5 |

| Met 24-pound weight loss goald | ||||

| N (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.5) | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| 95% CI | 0.0, 11.2 | 0.1, 17.8 | 2.2, 27.4 | 0.0, 11.6 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval

The response rate for the 24-week survey was 68%.

13 missing 24-week weights were imputed.

Difference between 1:1 match arm and control arm significant at P = 0.005. This difference remained statistically significant when we used only the 119 non-missing 24-week weights.

Based on 119 non-missing 24-week weights: 31 in the control arm, 29 in the no match arm, 29 in the 1:1 match arm, and 30 in the 2:1 match arm.

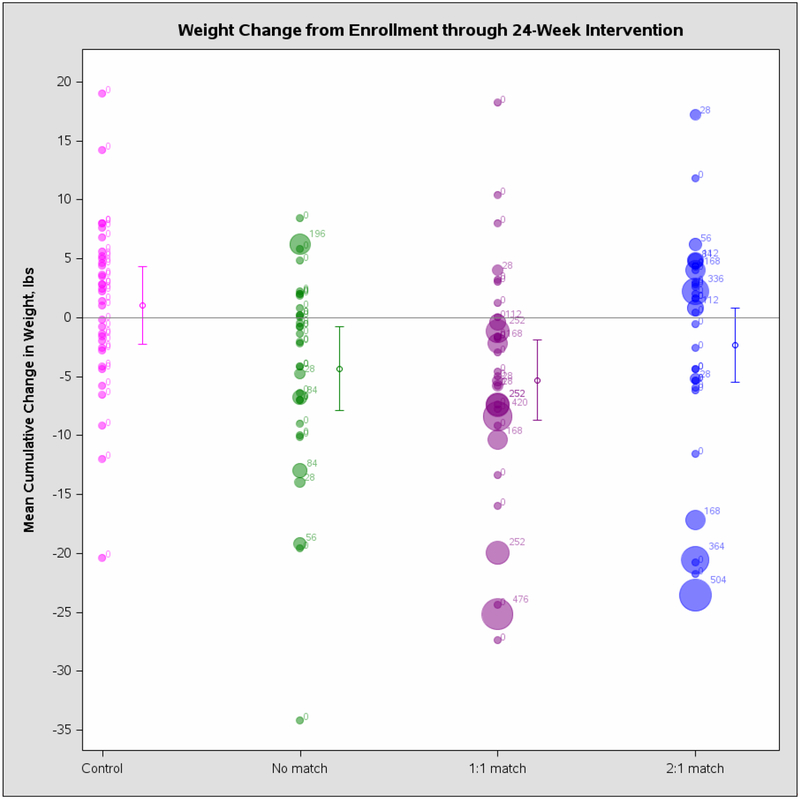

The lack of differences in deposit contract uptake limited the ability to draw inferences about the relationship between deposit contract participation in each arm and 24-week weight loss. However, for illustrative purposes a plot of each participant’s total deposit amounts and 24-week weight change by arm is shown in Appendix Figure 1.

There were no significant differences by arm in changes in potential mediators of weight loss such as eating behaviors, physical activity, or participation in weight-related wellness programs (Appendix Table 1). There were, however, significant differences in how often participants measured their weights on the workplace scales. In each intervention period month, participants in the deposit contract arms weighed themselves more frequently on the workplace scales than participants in the control group (P values ranged from < .0001 in month 1 to .001 in month 6). Over the entire intervention period, 2:1 match participants weighed themselves an average of 55.1 times (SD 32), 1:1 participants weighed themselves an average of 61.8 times (SD 33), and participants in the no match arm weighed themselves an average of 52.5 times (SD 33) as compared with control participants who weighed themselves an average of 17.2 times (SD 19, P < .0001).

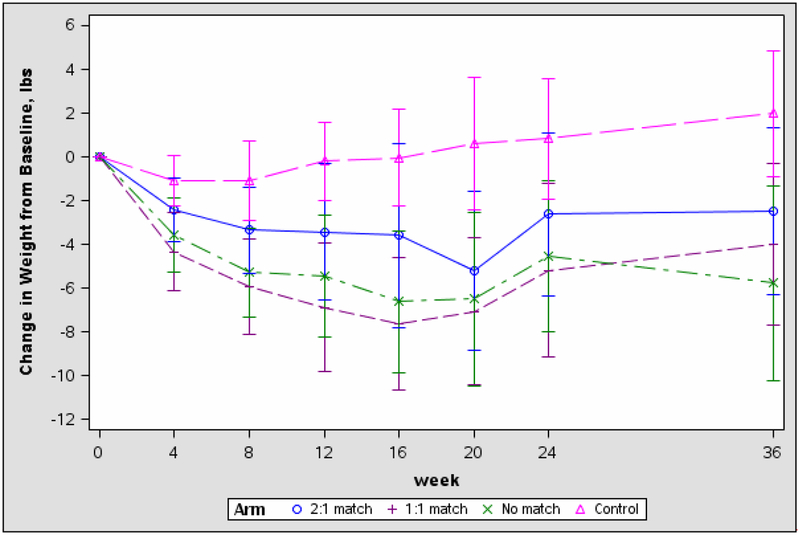

36 Week Outcomes

After 36 weeks (Figure 2), participants in the no match arm had significantly more weight loss relative to baseline (mean 5.1 pounds, SD 11.1) than control arm participants, who gained an average of 2.1 pounds (SD 7.9; P = .008) compared to baseline. Participants in the 1:1 match arm lost an average of 3.6 pounds (SD 9.6) compared to their baseline weight, which was no longer significantly different than the control group after the Bonferroni correction (P = .02). 2:1 match participants lost an average of 2.8 pounds (SD 10.1; P = .12 compared to control). There were no significant differences by arm in changes in factors that could potentially mediate weight loss after 36 weeks (data not shown).

Figure 2. Mean Cumulative Weight Change by Montha.

a16 missing 36-week weights were imputed. The difference between the no match and control arms at 36 weeks remained statistically significant when we used only the 116 non-missing 36-week weights.

Interviews with Deposit Contract Arm Participants

We conducted 57 interviews with participants in the 3 deposit contract opportunity arms: 9 of 10 participants who made 4 to 6 deposits, 15 of 19 participants who made 1 to 3 deposits, and 33 of 70 participants who made no deposits. From these interviews, key themes emerged about the main reasons participants did and did not enter into deposit contracts, and what they felt could have led them to make more deposits (Table 4).

Table 4.

Themes and Representative Quotes from Interviews with Deposit Contract Arm Participants

| Desire for extra motivation to lose weight was primary reason for deposit contract participation |

|

“The first month, especially the first month we made the deposit as like encouragement for me to actually like lose some weight. I figured if I put some money on the line then I would be more compelled to be active, eat healthier, eat right in order to lose weight.” “Well I figured that participating in that respect would give me extra encouragement to stick with it. I need all the encouragement I can get. I just felt it was an extra incentive to keep me on track.” |

| Lack of confidence in meeting weight loss goals limited participation in deposit contracts |

|

“I just honestly didn’t feel confident about like everything that was going on. I’m currently in school full-time and working full-time. I’m like—I’m not really gonna dedicate myself. I was gonna try, but I knew the likelihood of me actually like dedicating myself 100 percent to the study wasn’t there. I didn’t see a point in making the deposits.” “It was just harder for me to lose weight then for whatever reason. Each month I would try to look at it and go, you know I’m never gonna make this weight. Even if it was recalculated after a while, it was like I’m never gone lose this.” |

| Fear of -- and prior experience with -- losing money also limited participation |

|

“Basically I didn’t want to take any chances on losing any money.” “…I had a good momentum in the beginning. Then I started to lose that momentum. I think like towards August I was actually losing some money, so then I told myself you know what, I’m not gonna do it because I’m losing out.” |

| Greater personal commitment to weight loss could have led to more deposits |

|

“Nothing your company did or nothing the study did. It had to come from me actually.” “…It would have to be definitely on me, and being more of—more strict with making that effort to actually lose weight.” |

Among the 24 participants who made at least one deposit, 2 primary reasons for making deposits were cited by more than 5 participants. The predominant reason, mentioned by 18 participants, was they felt this would provide additional motivation to help them achieve their weight loss goals. One participant, for example, stated that “I figured if I put some money on the line then I would be more compelled to be active, eat healthier, eat right in order to lose weight.” Only 5 participants said they made deposits primarily to make money.

Three reasons for not making deposits were cited by 4 or more participants, among the 54 participants who passed up at least one opportunity to make a deposit, as the most important reason. The most frequent reason, cited by 14 participants, was a lack of confidence in achieving weight loss goals. One of these participants stated that “I guess I still have not hit that level of confidence and self-assuredness that I would succeed.” A related reason that 12 participants cited was fear of losing, or experience with losing, money they had deposited when they did not meet weight loss goals. One participant who had been making deposits, but then stopped, explained that “towards August I was actually losing some money, so then I told myself ‘you know what, I’m not gonna do it because I’m losing out.’” A less common reason, mentioned by 4 participants, was that the time periods in which they could make their deposits each month did not correspond well with their pay periods. One participant said, “The last date to make deposits was on a Wednesday. At the time our payroll would hit our bank accounts on Thursday. I remember that one month…I just didn’t have it to spare. Had it been the next day I could have done it.”

When asked about the principal changes that could have led to more deposits, 3 issues were each identified by at least 4 of the 54 participants who could have made more deposits. The most common change, mentioned by 24 participants, was being more committed to, and making a greater effort to achieve, weight loss. One participant, for example, stated, “Nothing your company did or nothing the study did. It had to come from me actually.” A less common change that could have potentially led to more deposits, cited by 5 participants, was if the monthly window in which they could deposits had immediately followed their payday instead of preceded it. Finally, 4 participants thought they might have made more deposits if they had simply paid greater attention to the automated study messages that described how and when to make deposits.

DISCUSSION

Relatively few study participants assigned to deposit contract conditions took up opportunities to enter into deposit contracts designed to promote weight loss, and employer matching of employee deposits did not increase participation. Nevertheless, there was greater weight loss in 2 of the deposit contract arms after 24 and 36 weeks than in a control group.

Our study has strengths and weaknesses. Strengths include the randomized design, the comparability of the study setting to the settings in which these types of approaches are now being offered, and our use of mixed methods. Weaknesses include our inability to determine the independent effects of deposit contracts and daily automated feedback on weight loss outcomes, since we did not have an arm that received daily automated feedback alone. Our follow-up data are limited to 12 weeks after incentives ended. A Bonferroni correction for the three pairwise comparisons may be overly conservative. The data we collected in semi-structured interviews with deposit contract participants may be prone to recall and social desirability biases.

While the overall 29.3% deposit contract participation rate in this study is comparable to participation rates in other settings in which deposit contracts have been tested,28–30 they are substantially lower than the participation rates of 89.5%11 and 95.5% that were observed in 2 other studies that offered deposit contracts to promote weight loss. These differences in participation rates are unlikely due to differences in participant characteristics, as participants in these 2 previous studies were generally of lower socioeconomic status than participants in the current study, and might therefore be less financially able to enter into deposit contracts. Instead, differences in the designs of the deposit contract interventions may help explain the differences in participation rates. In the 2 previous studies11,12, participants were Veterans who made their deposit contract decisions at a scheduled in-person medical center study visit in which they had just received $20 for completing a monthly weigh-in. In the current study, in contrast, participants made deposit contract participation decisions through a website without face-to-face contact with research staff, and they had not just received a payment that could easily be turned into a deposit. These differences suggest that human contact and money to seed the deposit account might be important ways to maximize participation in these interventions.

Our results have important implications for practitioners and policymakers. First, the interviews we conducted with deposit contract arm participants identified ways in which deposit contracts might be structured to maximize participation. The most frequently identified reasons for not making deposits and factors that could have led to more deposits all related to confidence in achieving weight loss goals. This suggests that approaches that either simultaneously enhance confidence in losing weight (e.g., offering deposit contract opportunities alongside an effective weight loss intervention) or target participants whose confidence in weight loss is already high (e.g., those who have already lost weight and are trying to keep it off) could be a way to enhance participation. Some participants also stated that they might have made more deposits if the time period in which they were asked to make deposits followed their payday. This slight modification to the deposit schedule could catch participants during a time in which they are feeling most financially able to make a deposit31 and therefore might lead to greater participation rates. Second, we found differences in weight loss between intervention groups and the control group despite the low deposit contract participation rates, which could have been owing to the frequent automated feedback participants in the deposit contract arms received. This automated feedback may have helped deposit contract arm participants stay more focused on weight loss than the control arm participants who did not receive these messages; more frequent weigh-ins among deposit contract arm participants could have been evidence of this effect. Three recent randomized controlled trials have tested automated messaging to promote weight loss and offer important context. Napolitano et al. found that overweight or obese college students who received daily text messages and access to a Facebook group lost an average of 5.9 pounds more over 8 weeks than those who had been given access to a Facebook group alone.32 Haapala et al. found that overweight or obese adults who used a mobile phone weight loss program that responded to participant data entry with an automated text message lost an average of 7.5 more pounds over 12 months than a control group.33 Patrick et al. found that overweight or obese adults who received daily tailored text messages over 16 weeks lost an average of 4.3 pounds more than those who did not. While each of these studies tested automated messaging in the context of interventions with other active components, their findings suggest that frequent automated feedback can be an effective tool for promoting weight loss and in our study may have been at least as important as the financial reward for goal attainment.

Most large US employers are offering financial incentives to promote healthy lifestyle activities among employees,2,34 and there is high interest in the use of deposit contracts to motivate behavior change in this setting. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will soon allow US employers to further increase the magnitude of outcome-based incentives to 30% of total health insurance premiums in 2014.35 As employers’ use of financial incentives to motivate healthy behaviors accelerates, this study suggests that simply offering an opportunity to enter into deposit contracts -- even when deposits are matched -- does not lead to high enough rates of sustained engagement to produce substantial weight loss. However, deposit contract opportunities with frequent automated feedback may lead to modest weight loss in these settings. Further work should explore ways to increase rates of engagement in these types of programs, and achieve synergy between this approach and other evidence-based weight loss strategies.

What is already known on this subject

Deposit contracts are a financial incentive strategy being used to promote weight loss among obese employees.

2 randomized trials have shown that deposit contracts can promote weight loss among obese people who want to lose weight.

A major challenge to wider impact of deposit contracts is getting high proportions of obese people to participate; one way to increase participation might be matching of deposits.

What this study adds

Employer matching of employee deposits did not increase participation in deposit contracts designed to promote weight loss.

Frequent automated feedback may have mediated weight loss in the deposit contract arms, and could be an efficient strategy to promote weight loss in workplaces.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grants from Horizon Healthcare Innovations, McKinsey & Company, and grant RC2103282621 from the National Institute on Aging. Support was also provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. These contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

APPENDIX

Multiple Imputation Methods

Multiple imputation was implemented using PROC MI in the SAS software package. The following variables were included as covariates to predict 24-week and 36-week weights: treatment arm, age, sex, race, education, household income, baseline weight, importance of controlling weight and confidence of controlling weight. The EM algorithm 34 was used to produce maximum likelihood estimates; because we had monotone missing data patterns, we utilized the parametric regression imputation procedure assuming multivariate normality and missing at random (MAR) data 35. After the five imputed datasets were obtained, the analyses described were conducted for each dataset separately; results from these analyses were combined using the standard formulae presented by Rubin 35, as implemented in PROC MIANALYZE in the SAS software package.

Appendix Figure 1. 24 Week Weight Change and Participant Deposit Amounts by Arma.

Each bubble represents an individual participant. The size of the bubble signifies the total amount (ranging from $0 to $504) that participant deposited over the course of the 24-week intervention.

Appendix Table 1.

24-Week Weight Loss and Behavioral Measures by Arma

| Measure | Control (n=19) |

No match (n=19) |

1:1 match (n=20) |

2:1 match (n=21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in physical activity in last 7 days, MET-minutes | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −669.3 (2752.2) | 5.6 (2357.3) | −335.1(2092.6) | 65.8 (2474.9) |

| 95% CI | −1922.1, 583.4 | −1067.4, 1078.6 | −1262.9, 592.7 | −933.8, 1065.4 |

| Change in cognitive restraint around eating | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −1.3 (11.1) | 2.1 (16.7) | 0.0 (14.1) | 8.5 (13.8) |

| 95% CI | −6.4, 3.7 | −5.5, 9.7 | −6.3, 6.3 | 3.0, 14.1 |

| Change in uncontrolled eating | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.6 (12.8) | 2.5 (14.7) | −0.7 (16.5) | −1.4 (13.5) |

| 95% CI | −3.2, 8.5 | −4.2, 9.2 | −8.2, 6.8 | −6.9, 4.0 |

| Change in emotional eating | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −1.1 (20.5) | 3.2 (18.6) | −0.5 (18.0) | −2.6 (20.2) |

| 95% CI | −10.4, 8.3 | −5.3, 11.7 | −8.5, 7.5 | −10.7, 5.6 |

| Started participation in weight-related program | ||||

| No./total (%) | 2/19 (10.5) | 1/19 (5.3) | 4/20 (20.0) | 2/21 (10.0) |

| 95% CI | 1.3, 33.1 | 0.1, 26.0 | 5.7, 43.7 | 1.2, 30.4 |

| Continued participation in weight-related program | ||||

| No./total (%) | 13/19 (68.4) | 15/19 (78.9) | 14/20 (70.0) | 18/21 (85.7) |

| 95% CI | 47.5, 89.3 | 60.6, 97.3 | 49.9, 90.1 | 70.8, 100 |

The response rate for the 24-week survey was 68%.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) [initials of relevant authors] had support from [name of companies] for the submitted work; (2) [initials of relevant authors] have [no or specified] relationships with [name of companies] that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have [specified] financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) [initials of relevant authors] have no [or specified] non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Role of the Sponsor: Neither the sponsors nor the funders had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Data Sharing: Statistical code available from the corresponding author at jkullgre@med.umich.edu.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA 2012;307(5):491–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.16th Annual Towers Watson/National Business Group on Health Employer Survey on Purchasing Value in Health Care: Towers Watson/National Business Group on Health 2011.

- 3.Claxton G, DiJulio B, Whitmore H, Pickreign J, McHugh M, Finder B, et al. Job-based health insurance: costs climb at a moderate pace. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(6):w1002–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinen L, Darling H. Addressing obesity in the workplace: the role of employers. Milbank Q 2009;87(1):101–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halpern SD, Asch DA, Volpp KG. Commitment contracts as a way to health. BMJ 2012;344:e522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bet dieting takes hold in the UK: BBC News, 2009.

- 7.Fox E Dieting for dollars. Philadelphia Inquirer 2012 January 18, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grayson PW. Dieting? Put your money where your fat is. New York Times 2009. February 4, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein J Making a resolution? Diet betting may offer incentive to lose weight. Los Angeles Times 2011. December 19, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979;47(2):263–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, Norton L, Fassbender J, Loewenstein G. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008;300(22):2631–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.John LK, Loewenstein G, Troxel AB, Norton L, Fassbender JE, Volpp KG. Financial incentives for extended weight loss: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26(6):621–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, Haffner SM, Hubbard VS, Johnson KC, et al. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials 2003;24(5):610–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aim for a Healthy Weight: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2005.

- 15.Swenson O Are we all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers? Acta Psychologica 1981;47(12):143–48. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connolly T, Butler D. Regret in economic and psychological theories of choice. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 2006;19(2):139–54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeelenberg M, Pieters R. Consequences of regret aversion in real life: The case of the Dutch postcode lottery. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 2004;93:155–68. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis MJ, Addis ME. Predictors of attrition from behavioral medicine treatments. Ann Behav Med 1999;21(4):339–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honas JJ, Early JL, Frederickson DD, O’Brien MS. Predictors of attrition in a large clinic-based weight-loss program. Obes Res 2003;11(7):888–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Cussler EC, Metcalfe LL, Blew RM, et al. Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004;28(9):1124–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35(8):1381–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angle S, Engblom J, Eriksson T, Kautiainen S, Saha MT, Lindfors P, et al. Three factor eating questionnaire-R18 as a measure of cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in a sample of young Finnish females. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2009;6:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Lauzon B, Romon M, Deschamps V, Lafay L, Borys JM, Karlsson J, et al. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R18 is able to distinguish among different eating patterns in a general population. J Nutr 2004;134(9):2372–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little RJA, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd Edition ed Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Summary: weighing the options--criteria for evaluating weight-management programs. Committee to Develop Criteria for Evaluating the Outcomes of Approaches to Prevent and Treat Obesity Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. J Am Diet Assoc 1995;95(1):96–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res 1998;6 Suppl 2:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charmaz K Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashraf N, Karlan D, Yin W . Deposit Collectors. Advances in Economic Analysis & Policy 2006;6(2):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashraf N, Karlan D, Yin W. Tying Odysseus to the Mast: Evidence from a Commitment Savings Product in the Phillippines. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2006;121(2):635–72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlan D, Zinman J. Put Your Money Where Your Butt Is: A Commitment Contract for Smoking Cessation. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2010;2(4):213–35. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zauberman G, Lynch JG. Resource Slack and Propensity to Discount Delayed Investments of Time versus Money. Journal of Experimental Psychology 2005;134(1):23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Napolitano MA, Hayes S, Bennett GG, Ives A, Foster GD. Using Facebook and Text Messaging to Deliver a Weight Loss Program to College Students. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haapala I, Barengo NC, Biggs S, Surakka L, Manninen P. Weight loss by mobile phone: a 1-year effectiveness study. Public Health Nutr 2009;12(12):2382–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health Care Changes Ahead: Towers Watson, 2011.

- 35.Volpp KG, Asch DA, Galvin R, Loewenstein G. Redesigning employee health incentives--lessons from behavioral economics. N Engl J Med 2011;365(5):388–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]