Abstract

Objective: To support clinically relevant indexing of biomedical images and image-related information based on the attributes of image acquisition procedures and the judgments (observations) expressed by observers in the process of image interpretation.

Design: The authors introduce the notion of “image acquisition context,” the set of attributes that describe image acquisition procedures, and present a standards-based strategy for utilizing the attributes of image acquisition context as indexing and retrieval keys for digital image libraries.

Methods: The authors' indexing strategy is based on an interdependent message/terminology architecture that combines the Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine (DICOM) standard, the SNOMED (Systematized Nomenclature of Human and Veterinary Medicine) vocabulary, and the SNOMED DICOM microglossary. The SNOMED DICOM microglossary provides context-dependent mapping of terminology to DICOM data elements.

Results: The capability of embedding standard coded descriptors in DICOM image headers and image-interpretation reports improves the potential for selective retrieval of image-related information. This favorably affects information management in digital libraries.

Images—such as x-rays, microscope slides, and photographs—are an essential part of the medical record. The improving cost-performance ratio of computer equipment is approaching the point at which digital image libraries will be routine in medicine. Digital image libraries have some well-known potential advantages over the present generation of analog image libraries, such as protection against loss of original images, provision for multiple simultaneous access, and enhanced information retrieval capability. The Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) standard 1 specifies a nonproprietary data-interchange format and transfer protocol for biomedical images, waveforms, and related information.1,2,3,4 The wide availability of DICOM-conformant image acquisition equipment makes it practical to exchange digital images even in a multivendor and multiplatform network. With a digital image library and a nonproprietary data interchange standard, medical images are theoretically accessible for review by any authorized health care provider. However, a digital image library and an “open” transfer protocol provide only a basic framework for image data interchange. The potential benefits of a digital image library will be obtained only if its contents, images, and image-related information are indexed with clinically relevant keys that enable selective retrieval of significant images, image-interpretation reports, and related information. In this paper we review the limitations of administrative coding systems and present examples from multiple clinical contexts that point to the need for clinically relevant indexing of digital image libraries. We describe the conditions and events that determine the information content of images. We conclude by presenting a multispecialty-consensus model of the clinically relevant attributes of image acquisition procedures, i.e., image acquisition context. The consensus model of image acquisition context is expressed in two formats: a SNOMED (Systematized Nomenclature of Human and Veterinary Medicine) DICOM microglossary template and a concise textual (pseudocode) representation of the logical elements of the DICOM acquisition context module.

Indexing of Biomedical Images

Indexing of images may be done a priori at the time of image acquisition; by code or text description at the time of diagnostic interpretation; or retrospectively, by extracting key words from an image interpretation report. A priori indexing at the time of image acquisition or interpretation requires a good user interface to reduce the burden on the user. Automated processing is desirable, but an ad hoc solution may not be feasible for a single institution. Standard codes and terminology increase the precision and reliability of both manual and automatic indexing. For the convenience of clinical personnel, both precoordinated and postcoordinated mechanisms must be available as needed. To ensure clinical relevance and to promote interoperability, context-dependent mechanisms must be provided to constrain the value sets and to define the network of semantic relationships that describe clinical attributes.

Whether done prospectively or retrospectively, indexing requires a semantic data model. Ad hoc semantic models (i.e., information retrieval models) may be used. However, there is substantial risk that these will not scale well. Ad hoc models are likely to include the following attributes: administrative attributes, such as the identification number of the imaging subject (the patient, specimen, or other entity that is the subject of the image); the identifier of the image acquisition procedure (e.g., the billing code of the “procedure”; an abstraction of the process, physical entities, and proximate events that generated the image); the administrative code that denotes the type of procedure; the date (and perhaps the time) of the procedure; and the name of the organization or person who performed the procedure. These five attributes are commonly displayed in the identification label of analog radiographs and therefore are the core of most ad hoc image retrieval models. Picture archiving and communication systems that use DICOM query and retrieval typically provide a query template that includes four categories of attributes to identify the patient, study, series, and image. Other DICOM attributes may be available as optional query keys, but queries on detailed clinical concepts may not be possible. For example, in older DICOM systems, the selection of anatomic regions of interest may be severely constrained. Some systems that provide “teaching file” capability may offer fields for diagnostic codes. However, ad hoc models are unlikely to include a comprehensive set of attributes that fully describe the clinically relevant aspects of image acquisition procedures, i.e., the image acquisition context.

The need for clinically relevant indexing of biomedical images is universal. However, ad hoc semantic models for image indexing typically are designed to serve the relatively narrow perspective of a single specialty or to support a limited set of clinical or operational contexts. This is natural, since context-dependent factors heavily influence the set of attributes that are relevant for a particular imaging modality and procedure type (e.g., computed tomography of the wrist versus endoscopy of the stomach) and the resources of any single institution or organization are typically invested to serve its own needs. The ad hoc approach may be appropriate for a single department, but it does not enable interinstitutional pooling of digital libraries for clinical, research, or administrative purposes. The specification of a generalized semantic model for image-acquisition context and the task of designing and building a controlled terminology resource for implementation of the model is ultimately the responsibility of the community. Therefore, an authoritative, nonproprietary consensus solution is needed.

A voluntary, cooperative initiative of industry, academia, government, and professional organizations was begun in 1993 to develop nonproprietary file formats, controlled terminology, and data interchange protocols for medical, dental, and veterinary color images.3,5 This multispecialty standardization project provided the opportunity to address the general description of image acquisition context with a standards-based approach. In the course of developing the color imaging supplement6 for the DICOM standard, the notion of image acquisition context was conceived as a means of specifying a single semantically adaptive message template that could be tailored to serve a wide variety specialized clinical and operational contexts. As we began to understand the image-related information needs of each specialty in the project, we realized that the attributes of image acquisition procedures correspond to a small set of semantic dimensions that are independent of the specialty imaging context—and that image acquisition is but a special case of data acquisition. This led us toward a generalized semantic model of data acquisition context and a model of image acquisition context that is a subset of the general model.

This paper describes the consensus model of image acquisition context that was developed for use with the DICOM standard. The intended scope of application is biomedical imaging. To enable this broad scope, a message/terminology mapping resource was created to serve as the repository of multispecialty context-dependent controlled terminology content.7,8 This mapping resource, the SNOMED DICOM microglossary (SDM),8 and the conceptual model for applying its content to message data elements or document fields (the interdependent message/terminology architecture) are described in previous papers.7,4,11,12,13 The SDM is a set of database tables that map terms and phrases from SNOMED9 and other controlled terminologies—such as the Logical Observation Identifier Names and Codes (LOINC) database,10 Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS, American College of Radiology, Reston, Virginia), and ISO-3950 (International Standards Organization dental codes)—to DICOM data elements and markup-language document fields (▶). Other specialized terminologies, such as the CANON (chest imaging) or UltraStar (pelvic ultrasound) vocabularies, which are authoritative resources in specialized domains, could be added to the SDM in the future.

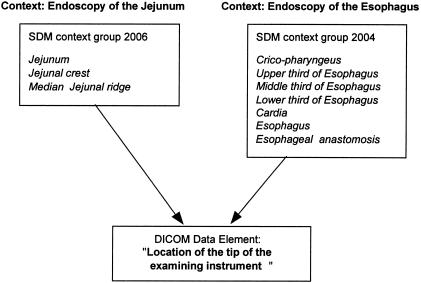

Figure 1.

Context-dependent determination of data element values sets by the SNOMED DICOM microglossary. Completely different sets of values are appropriate for this data element in the two closely related clinical contexts illustrated here. For clarity, coded concepts are depicted here as text strings rather than code values.

Although the content of the SDM is mapped to DICOM attributes, this does not limit the use of the content to DICOM messages. One of the most promising applications of the SDM is to provide context-sensitive terminology for extended markup language (XML) or standard generalized markup language (SGML) documents. Conversely, the DICOM encoding mechanism for coded entries supports the use of any code set (including local and private codes); there is no intrinsic exclusion of one system in favor of others. Standard code sets such as SNOMED are suggested where possible, in hopes that voluntary implementation of authoritative terminology will enlarge the sphere of shared understanding of important concepts.

The selected terminologies are authoritative and well maintained. The SNOMED and LOINC terminologies, in particular, were selected for biomedical imaging because of the willingness of their parent organizations to develop new domain-specific content on an ongoing basis with domain experts. Birads and ISO-3950 are the predominant coding systems in their respective subject areas. The SDM maps data elements or document fields to value sets (groups of terms) that are appropriate for a given context. SDM content, once approved by the SNOMED Editorial Board, becomes a part of SNOMED and ultimately will be included in the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) Metathesaurus. The SDM tables contain cross-reference fields for UMLS unique identifiers as well as other identifiers. Thus, although the acquisition and maintenance of biomedical imaging terminology are provided by SNOMED, the content of the SDM is designed to be accessible either from SNOMED or from the UMLS Metathesaurus. Cooperative development of SDM content is an ongoing project, administered by the College of American Pathologists on behalf of the other professional specialty society members of the DICOM Standards Committee.

Administrative Coding versus Clinical Relevance

Selective indexing and retrieval of diagnostic images is problematic in current practice. Indexing of images typically is done by billing codes assigned to the image acquisition procedure. This reflects the administrative perspective of imaging. However, the administrative coding scheme, typically the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) system,15 which was designed for billing and record-tracking purposes,14 does not allow indexing of many clinically significant attributes of the image acquisition context, such as the specific anatomic region examined and spatial, chemical, functional, or physical modifiers of image acquisition.

The U.S. Health Care Financing Administration requires the use of CPT codes to classify medical procedures for reimbursement for Medicare claims. As a result of the federal requirement, most other payers also accept CPT codes for insurance claims. Therefore, health care providers routinely record their data using these codes. However, CPT has been shown to lack the detail required for clinical data representation of health care processes and outcomes.16 The ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification) codes17 are often used in conjunction with CPT codes to convey the diagnosis associated with a procedure.14 Both systems are defined at too coarse a level to specify the detail needed for clinical decision making.

Example 1

A CPT code exists for “2-dimensional echocardiography, complete study” (93307), but no CPT code exists to describe imaging views or other specific attributes of echocardiography procedures. ▶ lists some of the attributes that must be considered for clinically relevant indexing of echocardiography procedures.

Table 1.

Procedure Description Attributes Having Clinical Relevance in Echocardiography

| Procedure Attribute | Examples |

|---|---|

| Imaging modality | M-mode echocardiography, pulsed-wave Doppler |

| Probe location | Parasternal, subcostal |

| View/orientation | Short axis, long axis |

| Region of interest | Mitral valve, aortic valve |

| Timing | Diastolic, end-systolic |

| Equipment | Vendor identifier, model number, software revision |

| Transducer | Probe type, probe frequency |

▶ lists some diagnostic interpretation attributes (diagnostic observations, including clinical recommendations) that may also be useful with procedure description attributes as indexing keys for echocardiographic images. Many of the attributes are appropriate for the description of cardiac findings, not only in the context of echocardiography but also in the context of angiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 2.

Observations That May Be Useful for Indexing Cardiac Images

| Interpretation Attribute | Examples |

|---|---|

| Measurements | Left-ventricular diameter, septal wall thickness |

| Timing | Systolic, diastolic, mid-systolic, end-diastolic |

| Findings | Left-ventricular enlargement, mitral leaflet thickening |

| Conclusions | Mitral stenosis, aortic valve endocarditis |

Example 2

To illustrate the level of detail needed for clinically relevant description of slide microscopy procedures, consider the microscopic images of a bone marrow biopsy and aspiration, accompanied by the pathologist's summary report. The CPT codes for these procedures would be 85095, Bone marrow aspiration; 85097, Bone marrow smear interpretation; 85102, Bone marrow biopsy; and 88305, Surgical pathology microscopic examination, Level IV, Bone marrow biopsy. It is apparent that all marrow biopsies would be indexed using this same set of codes, and virtually no other clinical information can be inferred from them. ▶ lists some of the attributes that may be useful for clinically relevant indexing of microscopic imaging procedures.

Table 3.

Procedure Description Attributes Having Clinical Relevance in Slide Microscopy of Bone Marrow

| Procedure Attribute | Examples |

|---|---|

| Imaging modality | Slide microscopy, general microscopy |

| Collected light type | Transmitted, emitted scattered |

| Immersion media | Air, oil, water |

| Polarization | Polarized, nonpolarized |

| Specimen collection | Thin-needle aspiration, core biopsy, open biopsy |

| Specimen stain | Hematoxylin and eosin, India ink |

| Specimen fixation | Alcohol, formalin |

| Equipment | Vendor identifier, model number, software revision |

As in Example 1, diagnostic interpretation attributes may be useful in conjunction with procedure description attributes as indexing keys for microscopic images. Consider the following interpretation of the bone marrow image described above: “day 21 status post allogeneic bone marrow transplant for acute myelogenous leukemia, hypocellular marrow with evidence of engraftment of erythroid and myeloid cell lines, no evidence of residual leukemia.”

Several attributes of the interpretation are recognizable: the procedure history (allogeneic bone marrow transplant, 21 days previously), pertinent diseases and diagnoses (acute myelogenous leukemia), the morphology of the marrow (hypocellular, erythroid engraftment, myeloid engraftment), and the interpretation of the findings (no residual leukemia). The additional clinical detail is readily encoded using SNOMED. In particular, the specific mention of myeloid and erythroid cell lines, as well as the bone marrow, are all derived from the SNOMED axes relating to normal anatomic structure (topography), function, procedures, and morphology:

DISEASES AND DIAGNOSES: M-98613: acute myelogenous leukemia, PROCEDURE HISTORY: P1-67D50: allogeneic bone marrow transplant, MORPHOLOGY: M-75300: hypocellular bone marrow (F-CC220: engraftment [of] T-C1100 erythroid cell line), (F-CC220: engraftment [of] T-C1200 myeloid cell line), INTERPRETATION: M-09420: bone marrow negative for residual neoplasm.

When pathology image transmission and storage are accompanied by this level of detail, retrieval and comparison of images is greatly facilitated. From a digital library that implements the DICOM and SNOMED standards according to the interdependent message/terminology described in this paper and others,4,7,12,13 it would be possible to retrieve and compare images classed as hypocellular versus normocellular and to assess the interobserver variability, clinical correlation, and prognostic significance of this finding.

Example 3

Cesarean delivery may be required in the presence of fetal hydrocephalus (ICD-9 653.6-mother 742.3-baby). The ICD-9 codes does not describe the specific cranial malformation of the fetus. To perform a multicenter study of the prognosis for the infant as a function of lateral ventricular size and gestational age, ICD-9 codes would be totally inadequate. Furthermore, if fetal hydrocephalus is diagnosed in utero by ultrasound, then procedure description data are essential to ensure that pooled data are equivalent. ▶ lists some of the attributes that must be considered for clinically relevant indexing of obstetric ultrasound procedures.

Table 4.

Procedure Description Attributes Having Clinical Relevance in Obstetric Ultrasonography for Evaluation of Fetal Cranial Abnormality

| Procedure Attribute | Examples |

|---|---|

| Imaging modality | Two-dimensional ultrasonography, color Doppler |

| Probe location | Suprapubic, subxiphoid, intravaginal |

| Beam path | Transabdominal, transvesical |

| View/orientation | Longitudinal, transaxial |

| Region of interest | Lateral ventricle (of fetus), fourth ventricle (of fetus) |

| Functional context | Maternal bladder full, maternal bladder empty |

| Equipment | Vendor identifier, model number, software revision |

| Transducer | Probe type, probe frequency |

A clinically relevant indexing system for obstetric ultrasonography would support the attributes of the image acquisition procedure and the attributes of diagnostic interpretation, such as measurements (e.g., biparietal diameter and ventricular diameter) and related findings (vertebral anomaly, porencephaly). A standards-based indexing strategy would greatly expedite pooling of measurement data for multicenter clinical trials, clinical efficacy studies, and outcome assessment.

Example 4

Chest radiographs—i.e., plain films, chest x-rays—are produced in larger numbers than any other type of radiographic image. A few CPT codes are available for chest x-rays, but the granularity is insufficient to describe the full range of attributes essential for clinically relevant indexing of chest x-rays. ▶ lists some of the attributes that must be considered for clinically relevant indexing of chest x-ray images.

Table 5.

Procedure Description Attributes Having Clinical Relevance in Chest Radiography

| Procedure Attribute | Examples |

|---|---|

| Imaging modality | Digital x-ray, computed radiography |

| View/orientation | Postero-anterior (PA), antero-posterior (AP), lateral |

| Projection modifier | Cephalad angulation |

| Spatial conditions | Upright position, standing, supine position |

| Physical conditions | Lead marker affixed to skin |

| Field of view | Full, coned-down |

| Beam epicenter | Dependent chest wall, diaphragm, minor fissure |

| Beam path | Left to right, right to left, posterior to anterior |

| Primary anatomic target | Left hilum, mediastinum, right posterior basal segment |

| Timing | End-inspiratory, end-expiratory, midexpiratory |

| Functional conditions | Breath-hold, breathing, positive end-expiratory pressure |

| Chemical conditions | Barium contrast agent, oil-based contrast agent |

| Equipment | Vendor identifier, model number, software revision |

| Receptor | Tungsten, selenium, charge-coupled device |

▶ lists some diagnostic interpretation attributes (diagnostic observations) that may also be useful in conjunction with procedure description attributes as indexing keys for chest x-ray images.

Table 6.

Diagnostic Observations That May Be Useful for Indexing Chest Radiographic Images

| Interpretation Attribute | Examples |

|---|---|

| Measurements | Diameter of a mass, cardiothoracic ratio |

| Findings | Cardiomegaly, pneumothorax, pulmonary nodule |

| Conclusions | Congestive heart failure, right lower lobe pneumonia |

| Recommendations | Chest fluoroscopy, percutaneous biopsy |

Image Acquisition Context

Image acquisition context includes the anatomic, chemical, functional, physical, spatial, and temporal conditions present at the time of image acquisition, such as anatomic region examined, contrast agent, vital stain, imaging modality, type of transducer, and position of the imaging subject during image acquisition. The attributes of image acquisition context have context-dependent value sets. The multispecialty consensus model of image acquisition context is utilized in DICOM Supplement 15: Visible Light Image for Endoscopy, Microscopy, and Photography,6 and DICOM Supplement 23: Structured Reporting.18 The DICOM standard, augmented by these supplements, specified nonproprietary and platform-independent protocols for interchange of biomedical images and related information, including interpretation reports, and makes possible robust description of clinically relevant attributes of image acquisition procedures. Digital image libraries that implement the DICOM standard will have at their disposal all the capabilities implied by these specifications.

Semantic Mapping and Interoperability

If one computer system is to accept and process data from another in a meaningful way, the information arranged within the data structures of the transmitting system must be rearranged into the data structures used by the receiving system. If this can be done, then the systems are said to be interoperable. Interoperability may not be possible if the systems are based on different models of the real world. In this case, all the information required by the receiving system may not be available and its function may thus be restricted. In addition, if the models fail to correspond in terms of the relationships between entities, the receiving system may be unable to understand the basic organization of the data. This could mean, for example, that the receiving system cannot determine which image belongs to which procedure. Technical incompatibilities between systems can usually be overcome by some means of bridge or translation, but if the systems do not share the same view of the data, resolving the resulting ambiguity will probably be impossible. The critical requirement is an unambiguous mapping of the semantic data models on which the data structures of the sending and receiving systems are defined.

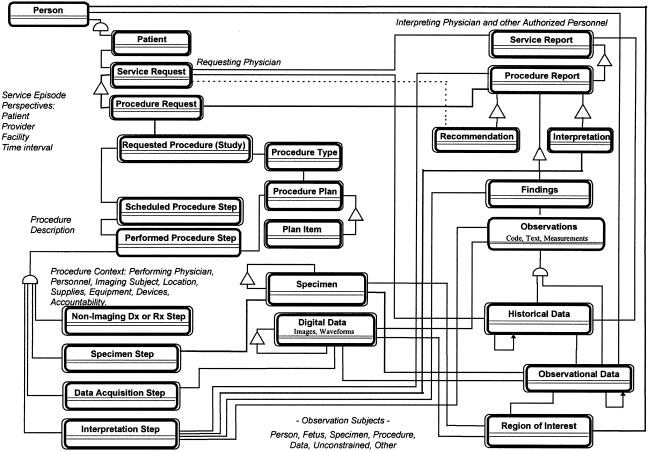

The following sections describe the semantics of image acquisition context, beginning with a high-level perspective and concluding with a synopsis of the data element structure that conveys image acquisition context in DICOM messages. ▶ depicts a domain information model of the abstract information system-imaging system (ISIS) interface on which the notion of image acquisition context is defined.3,11,18 ▶ summarizes the conditions or events that determine the information content of images. ▶ is a structured-text (pseudocode) representation of the DICOM image acquisition context module.6 An annotated template of the attributes of image acquisition context appear in the Appendix.

Figure 2.

Structured reporting domain information model.

Table 7.

Factors That Determine the Information Content of Images

| Imaging Procedure: |

|

| Imaging Modality: |

|

| Imaging Subject: |

|

| Image Acquisition Context: |

|

Table 8.

Synopsis of the DICOM Acquisition Context Module

| Acquisition Context Sequence: A data structure that conveys the conditions present during the acquisition of an image. Any number of repetitions of the following set of data elements {enclosed in braces} may be included in the acquisition context sequence. |

|

|

| Acquisition Context Description: Optional free-text description of data acquisition context. |

Image-related Information

A biomedical image is of no value without associated data, such as identification of the patient, identification of the study performed, other images, and relevant clinical information (i.e., image acquisition context). The information required depends on the domain in which it is being used. When an imaging procedure is performed, relevant administrative information, such as patient demographic data, is required by the imaging department. At other times relevant information about the imaging procedure, such as the status (e.g., scheduled, completed, reported) and the results, must be supplied by the imaging department and possibly made available at various physical locations such as the patient's ward, an out-patient imaging center, or the office of a private physician. Currently this information is often exchanged on paper. The requirement to implement this exchange between computer systems both inside and outside the imaging service department gives rise to a number of issues. In particular it is necessary to group the descriptive information in such a way that specific data can be made available to only those systems that require access to it in an efficient, reliable, and secure manner.

No real-world entity can be completely described. However, formal semantic analysis techniques enable domain experts to express the essential characteristics of real world entities (such as patients, providers, imaging procedures, and images) in graphic and verbal forms that can be used to define content specifications for documents, messages, user interfaces, and data-bases used by the application software of information systems to mediate real-world transactions. The level of descriptive precision that is necessary and sufficient for practical representation of the attributes (i.e., characteristics, properties, or defining relationships) and the corresponding context-dependent value sets of pertinent entities is readily determined by the consensus of domain experts. The products of this semantic analysis (data modeling) are graphic or textual “real-world models” or “domain information models.”

The structured reporting domain information model18 (▶) depicts the core set of clinically relevant entities referenced in the DICOM information object definitions for images (e.g., visible light, digital x-ray, mammography, intraoral radiography, ultrasound, nuclear medicine), waveforms (e.g., electrocardiogram, arterial pressure tracings), examination workflow (modality worklist, performed procedure step), and report (structured reporting). The attributes of these entities participate in clinically relevant foundational relationships that define image acquisition context and therefore determine the information content of images.3,11,18 ▶ shows the semantic data model derived by object-oriented analysis of diagnostic imaging in multiple specialty contexts. This model has served as the domain information model for multispecialty color imaging, workflow tracking, and structured reporting extensions of the DICOM standard made since 1993. The model depicts three types of relationships among real-world entities: In the figure, semicircles signify “generalization-specialization” relationships (“a patient is a person”); triangles signify “part-whole” relationships (“a procedure request is part of a service request”); direct linear connections depict object instance relationships other than generalization-specialization and part-whole (“a procedure request is related to a procedure report”). Single-line rectangles denote “class-only” objects; double-line rectangles denote “class-and-instance” objects.*

▶ was derived from the information system-information system (ISIS) context model3,6,11,20 and is consistent with the procedure description model developed by the Medical Imaging and Multimedia Working Group of the European Standardization Committee (CEN/TC 251 WG4)21 and with the CEN/TC 251 PT3-022 model of “request and report messages for diagnostic service departments.”22

Determiners of Image-information Content

▶ describes the conditions and events that ultimately determine the information content of images. These characteristics are the basis for the various categories of attributes on which clinically relevant indexing of images depends.

DICOM Acquisition Context Module

▶ is a structured textual representation of the DICOM acquisition context module. It illustrates, in pseudocode format, the conceptual model of the data elements that convey the attributes that describe data acquisition.6 A name-value-pair mechanism is used to associate an explicit semantic type (i.e., one of the attributes of image acquisition context) with a value expressed as free-text, categorical-text, coded-entry, or numeric data. The acquisition context sequence may convey any number of name-value pairs, i.e., any number of procedure description attributes (concept name) and the corresponding values (value). A summary free-text data element (acquisition context description) is provided for optional use.

Discussion

Lessons Learned

There is a need for more detailed clinically relevant description of imaging procedures and image interpretation findings.24 The DICOM Visible Light Image and Structured Reporting development projects provided the opportunity for multiple specialties to collaborate on semantic data models and controlled terminology. We learned some valuable lessons from problems encountered during development. At first, the different specialties proceeded independently. However, we soon recognized that since additional specialty image types and reports would be created continually, it would be more efficient in the long run to establish generic templates for the attributes of diagnostic images and reports and to tailor those templates for specialized uses with controlled terminology developed by the appropriate group of domain experts. Specialized terminologies—such as the endoscopic terminology of the American and European Societies for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the ISO-3950 dental nomenclature, and the BI-RADS breast imaging lexicon were favored by their respective clinical users as the terminology standard for their subspecialty. However, over time our understanding of the desirable properties of large-scale code sets improved, and we recognized that each of the ad hoc code sets, although rich in domain-specific content, has technical limitations, such as duplication of identifiers and lack of cross-referencing with other coding systems. It was recognized that these limitations could be ameliorated by making the contents of the ad hoc terminologies available through the SDM with unique identification, full mapping to SNOMED, and ultimately cross-referencing to the UMLS Metathesaurus.

In addition to the technical issues, there were significant administrative obstacles to overcome. Progress was achieved through an open, cooperative process of noncritical discussion, whereby mutual trust was established and common goals were recognized. Participants were instructed, as they considered technical issues from their own perspective, to intentionally extrapolate each issue into its general case, from which other specialized perspectives, analogous to their own but in different fields, could be derived. This approach led to some fundamental insights, such as the unifying notion of image acquisition context and the consolidation of independent development projects into a single cooperative initiative. Initially, some of the organizations were reluctant to distribute their terminology via the SDM, because of concerns over loss of editorial control. This concern was removed by mutual agreement that the source of each specialized terminology would retain editorial control of its own content, with the multispecialty editing group (the SNOMED Editorial Board and the DICOM Structured Reporting Working Group) ensuring cross-specialty integration. Concerns over publication and pricing issues were removed by the generous agreement of the College of American Pathologists to publish the SDM nomenclature at no charge on the SNOMED World Wide Web site to the mutual benefit of all contributors and users.

We are continuing to learn during implementation of the model. As we train new groups, such as dermatologists and mammographers, to tailor the DICOM specifications for use in their specialty, we have needed to develop tutorial materials to bring newcomers quickly up to speed on the basics of the DICOM semantic model. Fortunately, we have observed that the templates and context groups needed to specialize the generic DICOM objects for new clinical contexts can be expressed in a simple spreadsheet format that is easily understood by clinicians with no special training in computer languages. The template and terminology content needed to tailor the DICOM Visible Light and Structured Reporting specifications is intuitive to clinicians. Their task is simply to express a structured expression of domain knowledge that is very familiar to them. We learned from early experience that newcomers to this material learn more efficiently from illustrations of simple examples taken from contrasting subject domains than from abstract presentations of the material. We have also used an iterative development process, whereby problems identified in prototype implementation of the model were corrected in later versions of the specification.

Desiderata for Digital Libraries

We have presented a standards-based methodology for utilizing the attributes of image acquisition context as indexing and retrieval keys for digital image libraries. A standards-based interdependent message/terminology architecture, consisting of the DICOM standard, SNOMED, specialty code set extensions of SNOMED, LOINC, and the SNOMED DICOM microglossary, provides the infrastructure to support detailed description of image acquisition procedures and image-interpretation findings.11 Robust indexing makes possible the selective retrieval of images and image-related information for use in clinical decision-making and in clinical outcome assessment.13

Retrieval of relevant images for clinical decision making in individual cases. Request: Retrieve images of John Doe, showing the degree of left ventricular dysfunction. Response: Two-dimensional echocardiographic images (full cardiac cycles) are retrieved, showing left ventricular function in four views.

Retrieval of serial/comparison studies in individual cases. Request: Show image comparison of mitral valve vegetation from last three echocardiogram studies for Jane Doe. Response: Views of mitral valve vegetation from last three studies are shown.

Retrieval of images by specific finding or conclusion. Request: Show all images with anterior mitral valve leaflet vegetation with size greater than 10 mm. Response: All images that show vegetations of significant size are shown.

Search across patient populations for teaching or research purposes. Request: Retrieve multiple images from echocardiography database to demonstrate methods of quantifying severity of aortic insufficiency (multiple modalities, view). Response: All color Doppler images in parasternal short-axis view at level of left ventricular outflow tract in patients with severe aortic insufficiency are shown to allow measurement of ratio of aortic value insufficiency jet to left ventricular outflow tract.

Integrate images across multiple modalities in individual cases, to assist in clinical decision making or teaching. Case: Patient in the intensive care unit with acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. Evidence: Chest x-ray shows cardiac enlargement and pulmonary edema. Echocardiogram shows decreased ejection fraction and anterior wall akinesis. Coronary angiogram shows total occlusion of left anterior descending coronary artery. Electrocardiogram shows anterior wall myocardial infarction with evolving ST segment changes. Intensive care unit monitor shows episode of ventricular tachycardia and atrial fibrillation. Pulmonary artery catheter waveforms show increased pulmonary artery wedge pressure.

Administrative coding schemes fall short of the goal of supporting clinically relevant indexing of digital image libraries. The additional clinical detail of SNOMED, LOINC, BI-RADS, ISO-3950, and other clinical code sets enables robust indexing of image acquisition procedures and diagnostic findings. One must keep in mind, however, that substantial application “intelligence” and functionality are needed to implement the desired functionality listed above, even if all the findings are encoded as discrete atomic concepts. Fortunately, the semantic models and clinical concepts are derived directly from clinical practice and are independent of the highly volatile technology used to represent them in application software and communication interfaces.

Future Work

The explicit semantic data model of DICOM not only enables devices to connect but enables interconnected devices to achieve a shared semantic understanding of the information that is exchanged.4 The context-dependent value sets and relationship constraints provided by the SDM significantly improve expressiveness and reduce ambiguity.7 However, the fact that content can be expressed in a standardized way does not mean that computers are completely able to process this representation. Synonymy, differences in granularity and compositionality (post-coordinated versus pre-coordinated), redundancy, and incompleteness (inability to express some of the concepts of one vocabulary in another) present major challenges to interoperability. The flexibility of the interdependent message/terminology architecture provides expressive freedom that enable efficient adaptation of an existing system to new applications.11 However, the same flexibility demands the definition of constraints.23 Interoperability can be improved by defining “expressive patterns” for frequently used concepts, such as those utilized in the DICOM Structured Reporting specification. A formal notation has been developed for this purpose.18,25 Specialty implementation guidelines for DICOM and constraints for the descriptions and their representations (i.e., a common style of using the SDM, suggested lists of pre-coordinated terms, and combinatorial rules for post-coordinated terms) are being developed by professional speciality organizations. Development and maintenance of SDM content is an ongoing process.7,12,13 At the time of this writing, the DICOM acquisition context module is available for trial implementation in the DICOM Visible Light and Structured Reporting specifications. The DICOM Digital X-Ray Working Group and the DICOM Cardiovascular Angiography Working Group have included the acquisition context module in their draft specifications. Thus, the domain coverage of biomedical imaging is sufficient to support prototyping of DICOM digital image libraries supporting multiple departments and specialties, with the intention of providing data for cross-disciplinary research, training, and clinical trials.

Conclusion

The DICOM standard specifies platform-independent interchange of biomedical images and image-related information.4 The explicit semantic data model of DICOM enables devices not only to connect but to achieve a shared semantic understanding of the information that is exchanged. Because of the efficiency and economy of its nonproprietary interface, the DICOM standard has been implemented widely in radiology and is now being adopted in cardiology, gastroenterology, pathology, ophthalmology, dentistry, and other specialties.3 The SNOMED DICOM microglossary (SDM) provides context-dependent controlled terminology for imaging procedure descriptions and image interpretation reports.7 The SDM is a resource for system architects, programmers, and database managers who are developing user interfaces and information-retrieval tools for DICOM imaging systems. The capability of storing explicitly labeled coded descriptors of image acquisition context from the SDM in DICOM image headers and structured reports improves the potential for selective retrieval of image-related information. This favorably affects the quality and clinical relevance of information obtainable from digital image libraries.

Appendix

Attributes of Image Acquisition Context

The following table ▶ is a general-purpose list of image acquisition context attributes from SDM template 2.6,8 This template depicts the subset of data acquisition properties that pertain to image acquisition. Many of these properties are relevant to the description of any type of data acquisition procedure (e.g., electrocardiography, hemodynamic measurements) or biomedical diagnostic procedure. When a value set (referenced context group, rcid#) is defined in the SDM for a property, the number identifying the context group is specified. In some properties, only the class of observation is specified (C indicates code; T, unstructured text; M, numeric measurement; N, named type). These observation classes indicate the type of data that is permitted to convey the value of the property; however, the value set is unconstrained. In one case, the value of the property (chemical agent administration protocol) is a template (defined separately elsewhere in the SDM).

Appendix Table.

Generic Attributes of Image Acquisition Context

| Property | rcid# | rtid# | Definition | Examples and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification: | ||||

| Label, image | 171 | Label for the image | Preliminary, mask, subtraction mask, precontrast, baseline, scout, post-contrast, pre-exercise, post-exercise. | |

| Label, imaging hard copy presentation media, sheet or strip | C, T, M, N | Label for a sheet or strip of image presentation media (e.g., radiographic transparency film, 35-mm cine film) | A coded-entry, text, or numeric value. | |

| Protocol name | C, T | Name of the acquisition protocol | Stress thallium. | |

| Person who performs data acquisition | N | Name of person who performs the data acquisition procedure | Radiologic or electrocardiographic technologist. | |

| Anatomic Conditions: | ||||

| Anatomic region examined | 1 | Anatomic region | Upper gastrointestinal tract, stomach, antrum, gastric mucosa. | |

| Anatomic region modifier | 2 | Modifier of the anatomic region | Left, right, inferior, superior, peripheral, central. | |

| Spatial Conditions: | ||||

| Imaging subject orientation with respect to gravity | 19 | Sequence that describes the orientation of the patient with respect to gravity | Typically used to describe PERSON observation subjects. | |

| Imaging subject orientation with respect to gravity, modifier of | 20 | Patient orientation modifier, required if needed to fully specify the orientation of the patient with respect to gravity | Typically used to describe PERSON observation subjects. | |

| Geometric projection | 22 | Sequence that describes the projection of the anatomic region of interest on the image receptor | Postero-anterior, antero-posterior, lateral, left posterior oblique. | |

| Geometric projection, cranio-caudad angulation, modifier of | 23 | Cranio-caudad angulation modifier | Cranio-caudad, cephalad. | |

| Temporal Conditions: | ||||

| Protocol sequence number | N, T, M | Sequence number of the current stage of the protocol | 1, 2, 3,.... | |

| Protocol stage name | C, T, N | Name of this stage of the protocol | Rest, stress, arterial, venous, capillary. | |

| Quantitative measurement | N, M, T | Quantitative measurement of time | Various intervals; context dependent. | |

| Date/time | N | Absolute date or time | Context dependent, e.g., data acquisition start time, contrast agent injection start time, time of catheter introduction. | |

| Chemical Conditions: | ||||

| Radiographic contrast agent | 12 | Radiographic contrast agent | Sodium diatrizoate, air, barium sulfate. | |

| Interventional drug | 10 | Interventional drug | Epinephrine, glucagon. | |

| Radiopharmaceutical agent | 25 | Radiopharmaceutical | Technetium 99-m sulfur colloid. | |

| Additional drug | C, T, N | Any chemical, drug or biological substance; category unrestricted | A coded-entry or text value; this is an unrestricted category. | |

| Vital stain | 168 | Vital stain administered | Note: Any number of vital stains may be used simultaneously. | |

| Chemical agent administration protocol | 14 | Attributes of chemical agent administration | For each agent administered: rate, dose, stop/start time, etc. | |

| Administration route, chemical or biological product | 11 | Drug administration route | For any category of chemical or biologic product. | |

| Dose, chemical or biological product | T, N, M | Dose of chemical or biological product | A text or numeric value. | |

| Timing, chemical or biological product | T, N | Timing of administration of chemical or biological product | A text or numeric value. | |

| Functional Conditions: | ||||

| Functional conditions present during image acquisition | 91 | Context dependent | Breath-hold, breathing, phonation, Valsalva maneuver, Mueller maneuver, rest, exercise, static, dynamic, blood pool phase, arterial phase, venous phase, capillary phase. | |

| Physical Conditions: | ||||

| Physical force applied during image acquisition | 89 | Context dependent | Inflation, valgus stress, varus stress, compression, distraction, shear stress. Note: Description of any significant physical force applied during image acquisition. Described properties include anatomic sites where force was applied, physical agent through which force was applied, type of force, and magnitude expressed in qualitative or quantitative terms. Zero to many items may be present. | |

| Qualitative modifier of physical force applied during image acquisition | 90 | Qualitative modifiers | Slight, light, mild, minimal, moderate, firm, full, heavy, strong, maximum, maximum tolerated. | |

| Quantitative measurement | T, N, M | Quantitative measurement of physical force | A numeric or text value. | |

| Measurement units | 82 | Units of measurement | Cm, mm, μm, ml, kg. | |

| Physical agent used to apply the force | 86 | Physical agent used to apply the physical force | Angioplasty balloon, compression paddle, knee brace. | |

| Anatomic structure, space, or region to which physical force is applied |

1 |

Anatomic structure, space, or region |

Note: Specialized context groups apply to varous modalities and operational or clinical contexts. |

|

| Note: rcid# indicates referenced SNOMED DICOM microglossary (SDM) context group identifier (containing the suggested coded-entry value set of the property); rtid#, referenced SDM template identifier (containing a set of related concepts that fully describe the property). C, T, M, and N signify classes of data (i.e., DICOM structured reporting observation classes),18 where C indicates coded-entry data; T, text data; M, numeric measurement; and N, named type (e.g., date, time, person name, bibliographic citation, uniform resource locator, and categorical text) data. All properties for which an rcid# is defined may be conveyed as either coded-entry or text data. | ||||

This work was supported in part by the National Library of Medicine, the Joseph F. Stein Foundation, the American College of Radiology, the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Dental Association, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the American Academy of Neurology, and the College of American Pathologists.

Footnotes

For a more detailed explanation of the notation, see Coad and Yourdon.19

References

- 1.Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM). NEMA PS3.1-PS3.12. Rosslyn, Va.: National Electrical Manufacturers Association, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1997, 1998.

- 2.Bidgood WD Jr, Horii SC. Introduction to the ACR-NEMA DICOM standard. Radiographics. 1992;12:345-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bidgood WD Jr, Horii SC. Extension of the DICOM standard to new imaging modalities and services. J Digit Imaging. 1996;9:67-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bidgood WD Jr, Horii SC, Prior FW, Van Syckle DE. Understanding and using DICOM, the medical image communication standard. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4:199-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benn DK, Bidgood WD Jr, Pettigrew JC Jr. An imaging standard for dentistry: extension of the radiology DICOM standard. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1993;76:262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bidgood WD Jr (ed). Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM). NEMA PS3 Supplement 15: Visible Light Image for Endoscopy, Microscopy, and Photography. Rosslyn, Va.: National Electrical Manufacturers Association. 1998.

- 7.Bidgood WD Jr. The SNOMED DICOM microglossary: controlled terminology resource for data interchange in biomedical imaging. Methods Inf Med. 1998;37:404-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bidgood WD Jr. (ed). The SNOMED DICOM Microglossary. Northfield, Ill.: College of American Pathologists, 1998. Available at CAP SNOMED Web Site, at: http://www.snomed.org/sdm.htm..

- 9.Coté RA, Rothwell DJ, Palotay JL, Beckett RS, Brochu L (eds). The Systematized Nomenclature of Human and Veterinary Medicine: SNOMED International. Northfield, Ill.: College of American Pathologists, 1993.

- 10.Huff SM, Rocha RA, McDonald CJ et al. Development of the Logical Observation Identifier Names and Codes (LOINC) Vocabulary. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5:276-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bidgood WD Jr. Documenting the information content of images. AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:424-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Korman LY, Bidgood WD Jr. Representation of the gastrointestinal endoscopy minimal standard terminology in the SNOMED DICOM microglossary. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:434-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Bidgood WD Jr, Korman L, Golichowski A, et al. Controlled terminology for clinically relevant indexing and selective retrieval of biomedical images. Int J Digit Libr. 1997;1(3): 278-87. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cimino JJ, Hripcsak G, Johnson SB, Clayton PD. Designing an introspective, multipurpose, controlled medical vocabulary. Proc 13th Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1989: 513-8.

- 15.Physicians' Current Procedural Terminology (CPT). 4th ed. Chicago, Ill.: American Medical Association, 1989.

- 16.Chute CG, Cohn SP, Campbell KE, Oliver DE, Campbell JR. The content coverage of clinical classifications. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3(3):224-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 1975. Also available from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C., DHHS publication (PHS) 80-1260.

- 18.Bidgood WD Jr (ed). Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM). NEMA PS3 Supplement 23: Structured Reporting. Rosslyn, Va.: National Electrical Manufacturers Association, 1998.

- 19.Coad P, Yourdon E. Object-oriented Analysis. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Yourdon Press, 1991.

- 20.Bidgood WD Jr. A Common Data Repository for Message Components of Data Interchange Standards in the Domain of the Information System: Imaging System Interface. (Advisors: Friedman CP, Hammond WE, Lee JKT). Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1995.

- 21.Brown NGJ (ed). Medicom Imaging Scenario and Medicom Model (Clinical Scenario of Medical Imaging). European Standards Committee Technical Committee for Medical Informatics (CEN/TC 251), Working Group 4 (WG4). Amended by the British Mirror Panel of CEN/TC 251/WG4: Document IST/35/-4/NB109. Draft 1.1. Jan 2, 1996.

- 22.Markwell D (ed). Request and Report Messages for Diagnostic Service Departments. Medical Informatics CEN/TC 251/N95-027 Draft First Working Document (Red Cover Procedure), CEN/TC 251/PT3-022 BC-IT-M-021. Vol 1.1. Aug 8, 1995.

- 23.Rossi Mori A, Galeazzi E, Fabrizio Consorti F, Bidgood WD Jr. Conceptual schemata for terminology: a continuum from headings to values in patient records and messages. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:650-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.McDonald CJ, Overhage JM, Dexter P, Takesue BY, Dwyer DM. A framework for capturing clinical data sets from computerized sources. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:675-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bidgood WD Jr. Concise syntax for representation of DICOM SR expression patterns. Available at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center/Center for Telemedicine: SMARTLabs. Web Site, at: http://www.ctm.ouhsc.edu/smartlabs.ref.