Abstract

Background

Trihelix transcription factors (TTF) play important roles in plant growth and response to adversity stress. Until now, genome-wide identification and analysis of this gene family in foxtail millet has not been available. Here, we identified TTF genes in the foxtail millet and its grass relatives, and characterized their functional domains.

Results

As to sequence divergence, TTF genes were previously divided into five subfamilies, I-V. We found that Trihelix family members in foxtail millet and other grasses mostly preserved their ancestral chromosomal locations during millions of years’ evolution. Six amino acid sites of the SIP1 subfamily possibly were likely subjected to significant positive selection. Highest expression level was observed in the spica, with the SIP1 subfamily having highest expression level. As to the origination and expansion of the gene family, notably we showed that a subgroup of subfamily IV was the oldest, and therefore was separated to define a new subfamily O. Overtime, starting from the subfamily O, certain genes evolved to form subfamilies III and I, and later from subfamily I to develop subfamilies II and V. The oldest gene, Si1g016284, has the most structural changes, and a high expression in different tissues. What’s more interesting is that it may have bridge the interaction with different proteins.

Conclusions

By performing phylogenetic analysis using non-plant species, notably we showed that a subgroup of subfamily IV was the oldest, and therefore was separated to define a new subfamily O. Starting from the subfamily O, certain genes evolved to form other subfamilies. Our work will contribute to understanding the structural and functional innovation of Trihelix transcription factor, and the evolutionary trajectory.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-018-5051-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Foxtail millet, Trihelix, Transcription factor, Grass, Evolution, Selection

Background

Transcription factor is a type of DNA binding protein, and interacts with cis element of promoter regions of target genes, regulating the expression of them. At present, more than 60 transcription factor families have been found in plants [1]. Trihelix transcription factor is among the earliest transcription factor families discovered in plants [1].

Trihelix transcription factors (TTF) feature a conservative domain containing three series of alpha helix structure [2, 3]. TTFs were reported to play multiple regulatory roles in plant growth, development process, and response to adversity stress [4–7]. According to the changes in their alpha helix domain [8], they were previously divided into five subfamilies, respectively referring as I(or SH4), II(or GT-1), III(or GTγ), IV(or SIP1), and V(or GT-2). Each subfamily was named as to their respective first member found. Pea (Pisumsativum l.) GT-1 factor is the earliest identified TTF, which specifically combined with GT elements of light-induced gene rbcS–3A’s promoter [4]. In tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) [6], Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) [7], and rice (Oryza sativa) [5], homologous GT-1 genes were cloned. GT-2 was the first GT-factor isolated, containing two separate Trihelix domains [9, 10], each involved in DNA binding. Arabidopsis’s ETAL LOSS (PTL) gene belongs to the GT-2 family, and can regulate the growth of petals and sepals. It was also found to regulate flower organ formation of shape [11–13]. Rice SHATTERING1 (SHA1) gene, encoding a SH4 type of transcription factor, is the only identified member found in the SH4 subfamily, playing an important role in cell differentiation activation. A mutant SHA1 gene was found to cause the disappearance of the seed holding in rice [14]. GTγ subfamily has four members identified in rice, OsGTγ-1、OsGTγ-2、OsGTγ-3, and OsGTγ-4, which were related to cold, drought, and salt stress response [15]. Certain SIP1 genes have been identified in the tobacco and Arabidopsis, related to the development of plant embryo, leaf development, and cell proliferation [16–18]. Recently, expression profiles of Trihelix genes were available in tomato [19] and Populus trichocarpa, under biotic and abiotic stresses in the latter [20]. A new gene BnSIP1 was discovered in Brassica napus [21] mediating abiotic stress tolerance and ABA signaling.

Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) is one important arid and semi-arid crop, being a staple diet for people in some regions in China, India, and other Asian countries. Owing to its economic importance, its genome was sequenced [22, 23], together with further sequencing efforts [24–27], providing a rich genomic and genetic resources for biological research and breeding practice [28]. These precious efforts and accumulating resources empower researches in the Setaria community. Recently, tens of researches were performed to understand key functional gene families of the crop [29–43]. These researches described certain important transcription factor genes and gene families, such as Dof genes, encoding a class of transcription factors involved in numerous physiological and biochemical reactions affecting growth and development [43], TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA 1 genes, encoding a WD40 repeat transcription factor with multiple roles in plant growth and development, particularly in seed metabolite production [41], lipid transfer protein genes (LTPs), encoding a class of cysteine-rich soluble proteins having small molecular weights [38], MYB genes [44], APETALA2/ethylene-responsive element binding factor (AP2/ERF) genes [45], NAC genes [46] and so on .

Here, we identified TTF genes in foxtail millet, and characterized their molecular characteristic, genome distribution, and possible biological function. Moreover, by performing an evolutionary genomics analysis in selected plants, moss, green algaes, and yeast, we explored the evolution and origin of the TTF genes and inferred their possible evolutionary trajectories about their origin and divergence.

Methods

Data collection

Genome data of foxtail millet, rice, and sorghum were downloaded from JGI database (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/). To identify putative Trihelix family members, the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles of Trihelix (PF13837) were retained from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/) and were used to identify the putative Trihelix proteins with the best domain e-value cutoffs of < 1 × 10− 4. The rice Trihelix sequences [1] were used as the query to perform a BLASTP search in these species [47], with a cutoff e-value of< 10− 10. By using SMART program [48] (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), we detected the candidate protein by characterizing the typical Trihelix feature structure domain. We checked the ExPASy database (http://www.expasy.org/) to retrieve information as molecular weight, isoelectric point of TTF proteins [49]. Based on the above method and TFDB 4.0 database (http://planttfdb.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) [50], we obtained TTF homologs from other species: Ae. tauschii, T. urartu, barley, Brachypodium, maize, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, Volvox carteri, Physcomitrella patens, and Selaginella moellendorffii.

Gene structure analysis

According to the downloaded gff3 annotation file, the required data is extracted and the format is modified by the home-made Perl program. By using GSDS 2.0 (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/), we analyzed genetic structure of TTF genes [51].

Motif identification

By using protein conservative motif online search program MEME 4.11.3 (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme), we analyzed conservative motif of TTF gene family, and set the relevant parameters of motif repeat number to be “any”, motif length to be 6 ~ 200 aa, and motif prediction number to be 25 [52, 53]. By using WebLogo 3.6.0 (http://weblogo.threeplusone.com/), we characterized conservative region in amino acid sequence [54].

Gene localization and divergence

We used BioPerl program to estimate synonymous nucleotide substitution per synonymous site (Ks), and then drawing the circle diagram through the home-made Python program. All millet Trihelix genes are noted in the chromosome, genome evolution homologous duplicate events are connected by color lines with Ks. Ks: 0–0.35 black; 0.35–0.45 green; 0.45–0.65 red; 0.65–2 blue [55].

Multiple sequence alignment and evolutionary tree construction

Multiple sequence alignment of millet, rice, sorghum, Ae. tauschii, T.urartu, barley, Brachypodium and maize TTF gene family were performed by using Clustal X version 2.0 [56]. According to the sequence alignment, phylogenetic tree of TTF genes were built by PHYLIP 3.695 program with the Neighbor-joining method (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html), and the Bootstrap value 1000 was adopted.

Selection pressure analysis

Using PAML 4.8 Codeml program (http://abacus.gene.ucl.ac.uk/software/paml.html), we tested whether the sequences to bear the positive selection with four comparison models of M1a, M2a, M7, and M8 [57].

Orthologs in foxtail millet, rice and sorghum

Using OrthoMCL program (http://orthomcl.org/orthomcl/) [58], we analyzed chromosome segments duplication between foxtail millet, rice, and sorghum Trihelix genes, with the default settings, which initially required an all-against-all BLASTP, and then the relationships between the genes were deduced by the MCL clustering algorithm. The result is graphic by Circos software (http://circos.ca/) [59].

Expression analysis

Transcriptome and RNA - seq data was downloaded from the foxtail millet database (http://foxtailmillet.genomics.org.cn/page/species/index.jsp), and TTF expression data extracted by using home-made Perl program. The foxtail millet TTF genes expression cluster from each tissue was analyzed using Cluster 3.0 software (http://bonsai.hgc.jp/~mdehoon/software/cluster/software.htm), and the RPKM values were log2 transformed. The heat map of hierarchical clustering was visualized with TreeView1.1.3.

Protein interaction network

We used STRING 10.5 database (http://string.embl.de/) [60] to analyze millet TTF interaction with other foxtail millet proteins. We set the minimum required interaction score to be high confidence (0.700), and max number of interactors to be 5.

Results

Identification and genomic distribution

We identified 27 TTF genes in the foxtail millet genome database (Additional file 1: Table S1). The shortest sequence has 212 amino acid residues, while the longest one has 878 amino acid residues. The estimated protein molecular weights fall in a range 23,453.7~ 96,360.6, and the isoelectric points in a range 4.9184~ 11.2729.

The predicted 27 millet TTF genes have 36 transcripts (Additional file 2: Figure S1). Twenty-one genes (21 or 77.8%) were found to have a single transcript, while 6 of them have multiple transcripts, with Si7g009787 having the most (5). They have considerably divergent genic structures, with 1–17 exons. For example, 12 genes, e.g., Si6g014062, Si9g036682, have a single exon, while the gene Si1g016284 has 17 exons and its gene structure is broken into short pieces by inserted introns.

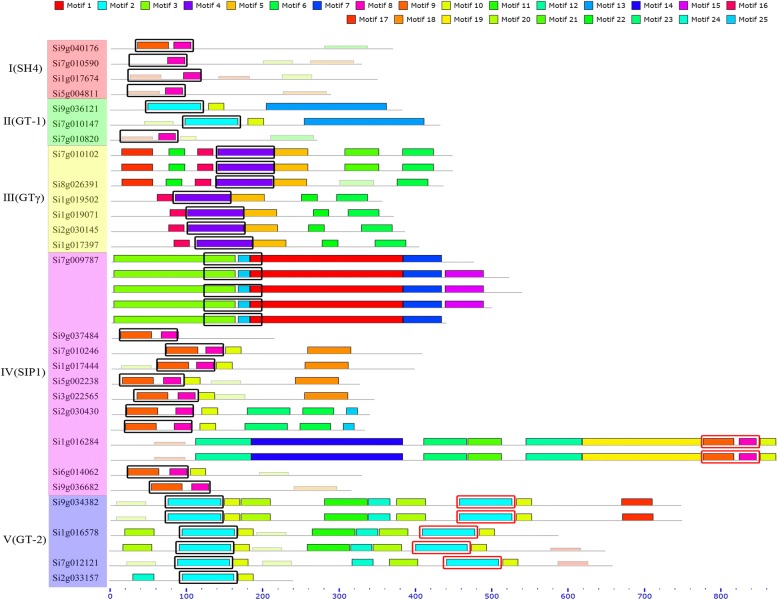

We characterized the motif in the TTFs and found that they are diverse in motif composition, supporting previous finding of divergent evolution with characterization of exons and introns. Identified motifs often contain > = 15 amino acid residues even 200 amino acid residues. Some motifs, such as Motif 8, are conserved in different subfamilies (Fig. 1), while other motifs shared by subfamilies are much variable (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Millet Trihelix transcription factor family conservative motif analysis. Dark color pieces were generated by MEME software, light color pieces show possible Motif (using a motif scanning algorithm). The areas enclosed by boxes are a conserved domain, black indicates the N-terminal, and red indicates the C-terminal

In foxtail millet, TTF genes in each subfamily have similar motif (Fig. 1). All six subfamily III genes contain Motif 4. The subfamilies I and IV feature the containing of Motif 8 and 9 while the subfamily II and the subfamily V features Motif 2.

TTF genes contain a conservative structure domain in the N terminal (except Si1g016284) (Fig. 1), while GT-2 contains the domain structure in the C terminal and 2 repeatitive and conservative structure domain. The GT-1 and GT-2 subfamilies are much more similar than to other subfamilies.

With the exception of Si1g016284, the other genes contain a conservative domain near the N-terminal, in which 1/5 of the amino acid residues are quite conservative, with Trp (W) - 1, Trp (W) - 64 and Cys(C) - 100 being highly conserved (Additional file 4: Figure S2).

According to gene localization in the foxtail millet genome, we found that, TTF genes are distributed in 8 foxtail millet chromosomes but chromosome 4, with chromosome 1 and 7 having 7 genes, chromosome 3, 6 and 8 having only 1 gene, and the others having 2–5 genes (Fig. 2). On chromosome 1 and 7, they form small clusters distributed in their middle and ending parts. Besides, there are 11 genes with Ks < 0.35, including a subfamily I gene (Si5g004811), 2 subfamily II genes (Si7g010147, Si9g036121), 4 subfamily III genes (Si1g017397, Si1g019071, Si1g019502, Si2g030145), 4 subfamily V genes (Si2g033157, Si1g016578, Si9g034382, Si7g012121), showing possible gene divergence after foxtail millet’s split from sorghum [55].

Fig. 2.

Millet Trihelix transcription factor family duplication analysis in the chromosome. All millet Trihelix genes are noted in the chromosome, genome evolution homologous duplicate events are connected by color lines with Ks. Ks: 0–0.35 black; 0.35–0.45 green; 0.45–0.65 red; 0.65–2 blue

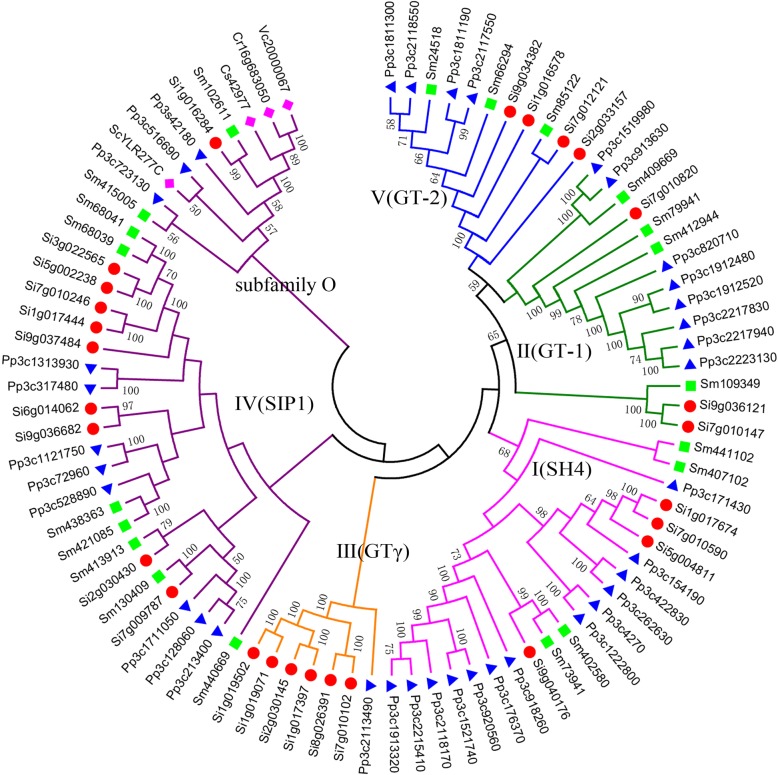

Evolutionary establishment of the family

To understand the evolution of the gene family, we involved their homologous genes from its grass relatives, rice (Oryza sativa), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), Aegilops tauschii, Triticum urartu, barley (Hordeum vulgare), Brachypodium (Brachypodium distachyon), and maize (Zea mays). Firstly, by using PHYLIP, we reconstructed the phylogenetic tree of TTF genes (Fig. 3). These grasses share genes from each subfamily, excepting T. urartu, in which none subfamily I gene was found in the present genome sequence. The subfamily IV has the most members in all species.

Fig. 3.

Reconstructed phylogenetic tree of grass TTF genes. Here, gene IDs show their respective origin: Os for rice, Si for Setaria italia, Sb for sorghum, Ae for Aegilops tauschii, Tu for Triticum urartu, Hv for barley, Bd for Brachypodium, and Zm for maize. We used shapes and colors to distinguish different species, with red circles, green circles, blue triangles, light pink triangles, blue squares, yellow squares, brown diamonds, deep purple diamonds to represent the TTF genes in Setaria italia, rice, barley, sorghum, maize, Brachypodium, Aegilops tauschii, and Triticum urartu, respectively. The number on the branches is support value by bootstraping

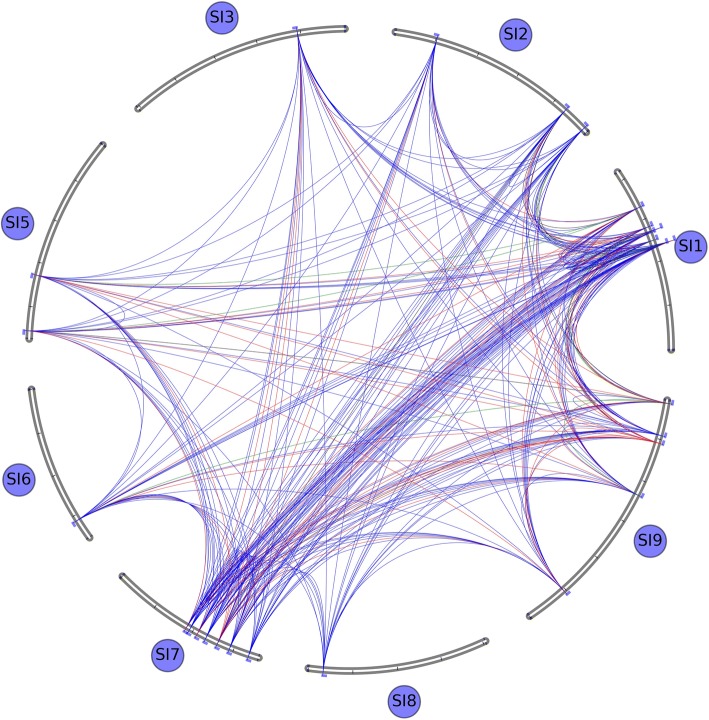

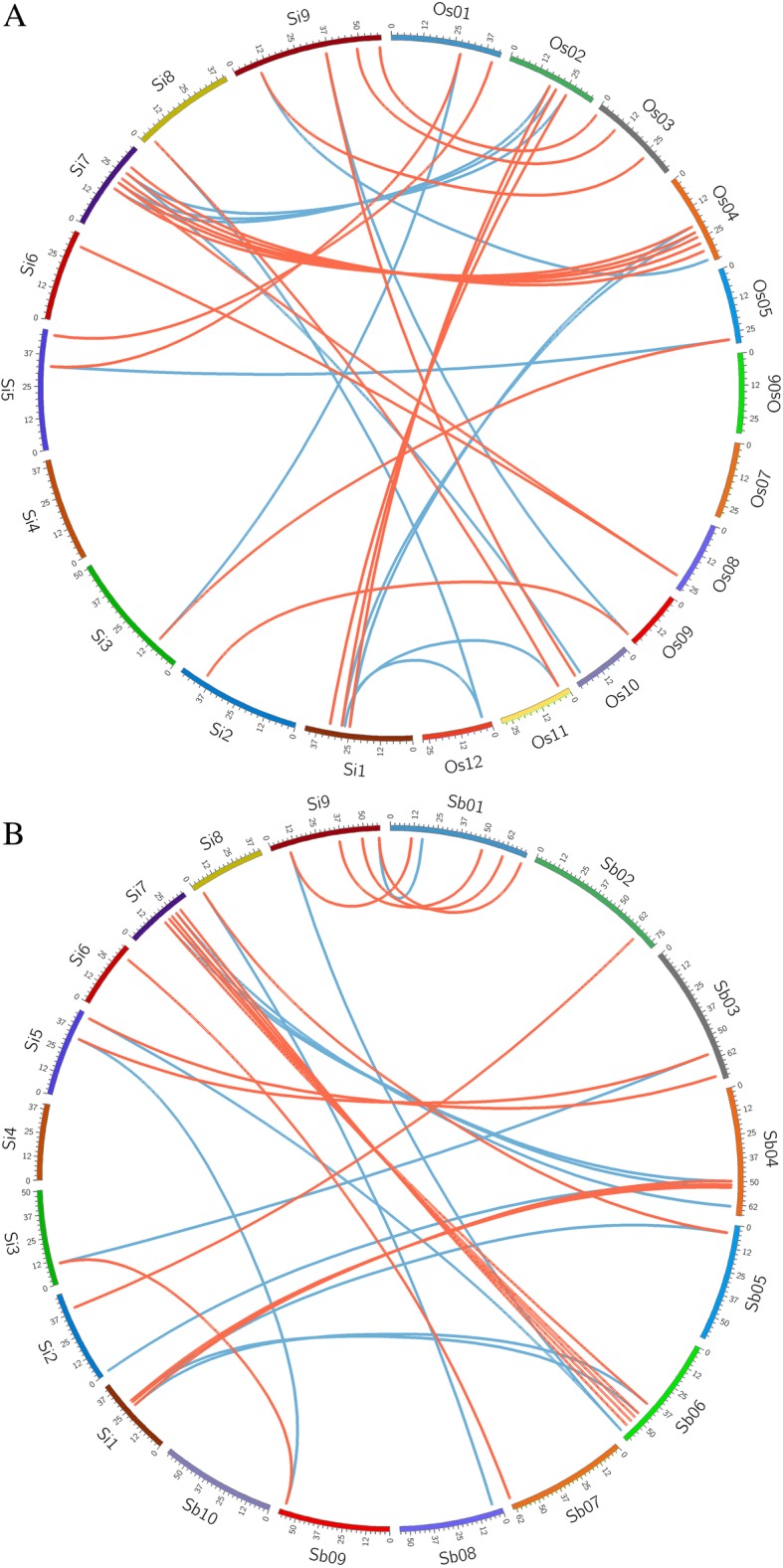

Through the OrthoMCL program, we identified 32 TTF homologous gene pairs in millet and rice, including 19 orthologous gene pairs and 13 non-orthologous ones (Fig. 4a). Millet and sorghum share 31 colinear genes, including 18 orthologs in colinearity (Fig. 4b). The orthologous pairs are those homologs at the anticipated genomic locations from two genomes and often the best 1–1 match. For a non-orthologous pair, a millet gene may have another non-best hit in the other grass, many quite likely related to the grass-common tetraploidization occurring ~ 100 million years ago. Often these non-orthologous pair could be called as outparalogous pair. A total of 9 genes (Si1g017444, Si1g017674, Si3g022565, Si5g002238, Si7g010246, Si7g010590, Si7g012121, Si8g026391, Si9g040176) are conservative in chromosomal locations in all 3 genomes, showing their existence in grass common ancestor.

Fig. 4.

Colinearity analysis of TTF genes between foxtail millet, rice, and sorghum. Chromosomes from any two grasses form a circle, and a pair of collinear TTF genes are linked with a curvy line in red and blue, showing orthologous pairs or paralogous ones. Millet chromosomes: Si1 ~ Si9; Rice chromosomes: Os01~Os12; Sorghum chromosomes: Sb01~Sb10. a: Millet-Rice. b: Millet-Sorghum

To find their a deeper history of the family, we reconstructed a phylogenetic tree involving homologs from representative organisms from different domains, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (green algae), Coccomyxa subellipsoidea (green algae), Volvox carteri (green algae), Physcomitrella patens (moss), Selaginella moellendorffii (fern), and foxtail millet (Fig. 5). Notably, the involved genes from these organisms can also be classified into 5 previously defined subfamilies (I~V) in grasses. There is only one TTF-like gene found in the algae and yeast (too old to form a Trihelix characteristic domain), while Physcomitrella patens and Selaginella moellendorffii have 37 and 20 TTF genes, respectively. A close check of the subfamily IV helped identify a certain group of genes, involving copies from the yeast and algae genes, and plant genes, therefore had existed before the divergence of major life domains. Therefore, we separated them from other subfamily IV genes, to define them as an extra group, or subfamily O. That is, with homologs from all species, we divided TTF genes into six subfamilies.

Fig. 5.

Reconstructed phylogenetic tree of TTF genes in involved species. Here, gene IDs show their respective origin: Si for Setaria italia, Pp for moss, Sm for fern, Sc for yeast, Cr for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Cs for Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, and Vc for Volvox carteri. We used shapes and colors to distinguish different species, with red circles, blue triangles, and green squares to represent TTF genes in Setaria italia, moss, fern, respectively and pink diamonds to represent TTF genes in yeast, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, and Volvox carteri. The number on the branches is support value by bootstraping

Genes forming subfamily IV were much diverged, involving the oldest lineages. Thus, we chose the subfamily IV to perform a natural selection analysis. By using the PAML Codeml program to perform likelihood ratio test, we estimated selective pressure on each lineage of the constructed tree. We found that 6 amino acid sites were likely subjected to significant positive selection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Natural selection pressure analysis

| Pr (w > 1) | post mean for w | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 S | 0.975* | 2.942 |

| 28 D | 0.585 | 1.851 |

| 81 L | 0.791 | 2.434 |

| 93 Q | 0.894 | 2.718 |

| 102 S | 0.874 | 2.663 |

| 103 K | 0.553 | 1.782 |

| 104 P | 0.816 | 2.497 |

| 105 L | 0.949 | 2.869 |

| 106 A | 0.962* | 2.903 |

| 107 T | 0.974* | 2.937 |

| 108 A | 0.876 | 2.669 |

| 109 E | 0.878 | 2.673 |

| 115 E | 0.549 | 1.764 |

| 130 R | 0.782 | 2.409 |

| 138 M | 0.961* | 2.903 |

| 141 S | 0.888 | 2.701 |

| 142 V | 0.948 | 2.865 |

| 144 V | 0.754 | 2.328 |

| 165 A | 0.971* | 2.931 |

| 172 V | 0.960* | 2.900 |

| 183 T | 0.948 | 2.865 |

| 186 A | 0.866 | 2.640 |

Positively selected sites (*: P > 95%; **: P > 99%)

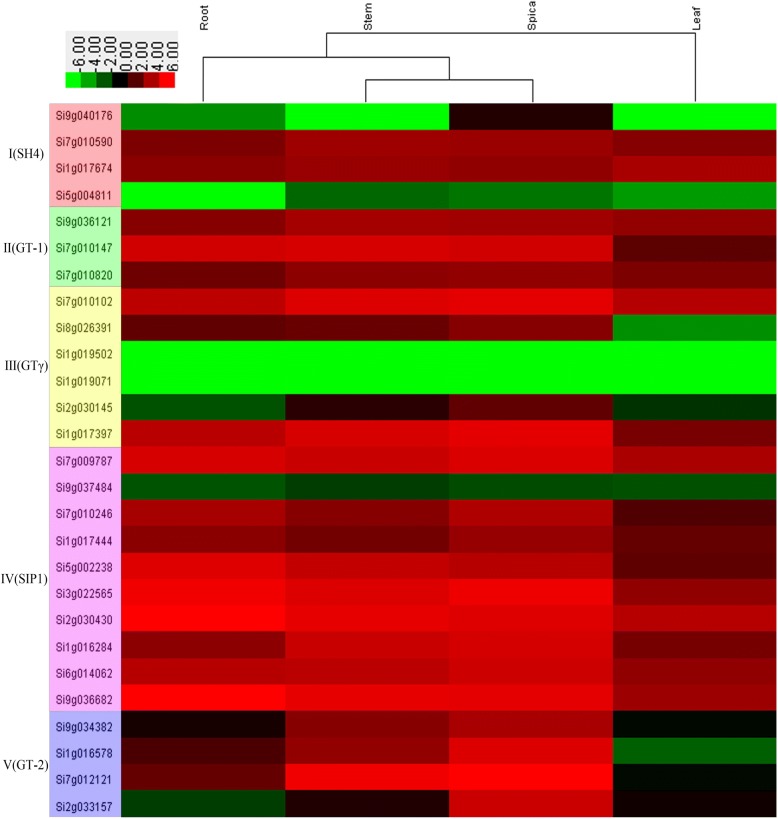

Expression profile in the different organs

We adopted heat map to display expression profile of millet TTF genes from different tissues, involving root, stem, spica and leaf (Fig. 6, Additional file 5: Table S3). Here, we define the standard for high expression gene is more than the average expression of all genes(the average RPKM value is 15.7). There were 9 genes (33.3%), 11 genes (40.7%), 14 genes (51.9%) and 3 genes (11.1%) with high expression in root, stem, spica and leaf, respectively. In all organs, genes in spica had the highest expression level. Subfamily IV had the highest expression level in all subfamilies. Si1g019071 and Si1g019502 were not observed to be expressed in any tissues, Si5g004811 not in the root, and Si9g040176 not in the stem and leaf.

Fig. 6.

Expression of millet Trihelix transcription factor genes in the different organs

In addition, expression has been down-regulated in many structurally variable genes. Si9g040176 had more copies of Motif 9 than others in subfamily I, possibly subjected a recent motif addition and is down-regulated. In subfamily III Si8g026391 had fewer copies of Motif 21 than the genes Si7g010102, and Si9g037484 had the simplest structure in the subfamily IV indicating a motif deletion, and they are also down-regulated. In the subfamily V, compared to other genes, Si2g033157 lost the domain in the C terminal region, and it is down-regulated. In contrast, though Si7g009787, having the most transcripts, and Si1g016284, being the oldest gene in the family, are each variable in structure, they had higher expression, showing possible functional benefit of plants due to their variable structure.

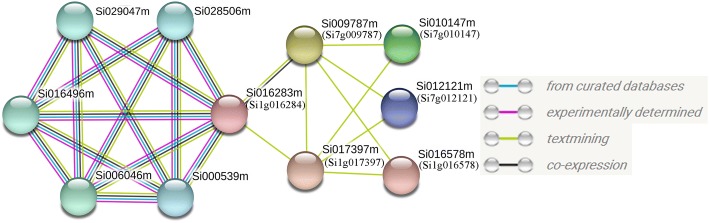

Protein-protein interaction

Protein interaction analysis shows that six of the foxtail millet Trihelix transcription factor families have interaction relationship (Fig. 7). Among them, Si1g016284 belongs to subfamily O, Si7g009787 belongs to subfamily IV, Si1g017397 belongs to subfamily III, Si7g010147 belongs to subfamily II, Si7g012121 and Si1g016578 belong to subfamily V. The protein-protein interaction information is from curated databases and experimentally determined. In addition, we also introduced textmining and co-expression to enrich the interaction information. We found that Si1g016284 from subfamily O has the most interaction with other proteins (7). It also has interaction with Si7g009787 and Si1g017397, which have five interacting proteins respectively. The genes, Si7g010147, Si7g012121 and Si1g016578 have two interacting proteins respectively.

Fig. 7.

Interaction network diagram of Trihelix transcription factor and other proteins in foxtail millet

The oldest TTF gene, Si1g016284, played a significant role in the interaction. It seems to serve as a bridge connecting the Trihelix family and other millet proteins, and is co-expressed with many proteins (6), suggesting that these proteins function synergistically. Structurally, Si1g016284 has two extra domains, Lactamase_B and RMMBL, in addition to the characteristic of the Trihelix family. The five non-Trihelix proteins interacting with it have variable domains, such as Lactamase_B, RMMBL, Beta_Casp, CPSF100_C, WD40, ZnF_C3H1, YTH, and/or HAT, showing a multiple-facet nature of Silg016284.

Discussion

As a multi-functional transcription factor family, TTFs were the first ones identified in plants [1]. Here, starting from research in foxtail millet and extending into other organisms, we explored their functional changes, expressional features, genomic duplication and phylogenetics. Eventually, we identified an oldest subfamily, referred as O, in the constructed phylogenetic tree. Interestingly, the single foxtail millet gene Si1g016284 in subfamily O is the one having the most exons (Additional file 2: Figure S1). It has a single ortholog in yeast or any algae species, and two orthologs in fern and three orthologs in moss. Actually, this seems to be weird in that we would have expected that it might be the most conservative one to have highest similarity with the homologs from far diverged life domains. This shows that, though broken into 17 segments, the gene might have not been pseudogenized but rather likely functional.

Starting from the subfamily O, primitive TTF genes continued to expand in the plant domain. As to the reconstructed tree topology, we found that certain genes evolved to form subfamilies III and I, and later from subfamily I to develop subfamilies II and V (Fig. 5).

In each subfamily, there is evidence that genome duplications contributed to accumulate more copies. For example, in foxtail millet, a group of genes in subfamily IV appeared after its divergence from other grasses (Fig. 3), and moss has the most TTF genes with new copies seemingly having been continuously produced (Fig. 5).

The primitive TTF gene, Si1g016284, has conserved domain in its C terminal region, as genes forming subfamily O from different life domains. Contrastively, the conserved domains were found in N terminal or both terminals in the other foxtail millet genes (Fig. 1).

Besides, subfamily GTγ were not found in Lycophta and S. Moellendorffii (Fig. 5), consistent to previous report [61]. This shows that though as an old subfamily, they may have been pseudogenized or removed from certain plants.

Conclusions

TTF genes were previously divided into five subfamilies, I-V. By performing phylogenetic analysis using non-plant species, notably we showed that a subgroup of subfamily IV was the oldest, and therefore was separated to define a new subfamily O. Starting from the subfamily O, certain genes evolved to form other subfamilies. The oldest gene, Si1g016284, has the most structural changes, and a high expression in different tissues. What’s more interesting is that it may have bridge the interaction with different proteins. Our work will contribute to understanding the structural and functional innovation of Trihelix transcription factor, and the evolutionary trajectory.

Additional files

Table S1. Basic information of foxtail millet Trihelix transcription factor genes. (DOCX 15 kb)

Figure S1. Millet Trihelix family genetic structure analysis. (JPG 1489 kb)

Table S2. Conservative motif in Trihelix transcription factor genes. (DOCX 13 kb)

Figure S2. Trihelix family conservative domain feature analysis in foxtail millet. Stack height in different sites of amino acid shows conservative domains, the stack height of a single amino acid shows the relative frequency of the amino acid in this location. Red triangle shows that conservative core amino acids Trp (W) - 1, Trp (W) – 64 and Cys (C) -100. (JPG 740 kb)

Table S3. RPKM values of millet Trihelix transcription factor genes in the different organs. (DOCX 17 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank the center for genomics and computational biology lab team for discussion and support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Youth Foundation of Educational Committee of Hebei Province (grant no. QN2017123), Undergraduate Training Programs for Innovation and Entrepreneurship of North China University of Science and Technology (grant no. X2016161) to KZ, National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31371282) to XW, National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31501072) to TL, National Science Foundation of Hebei province (grant no. C2016209097) to WG, China-Hebei 100 Scholars Supporting Project (grant no. E2013100003) to XW.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study were included in this published article and the Additional files. We have been using public data and do not have produced sequence data by ourselves.

Authors’ contributions

XW, ZW and KZ designed the experiments and organized the manuscript. ZW, KZ, XS, WG, JW, MY, TL, LW, LZ, YL, TL, WC, WM, CS, XC, YB, YP and XW performed the experiments. ZW and KZ wrote the manuscript. XW, YP and XS edited the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhenyi Wang, Email: zhenyiwang0301@163.com.

Kanglu Zhao, Email: 15632709889@163.com.

Yuxin Pan, Email: panyu-xin@163.com.

Jinpeng Wang, Email: wangjinpeng1010@vip.sina.com.

Xiaoming Song, Email: songxm@ncst.edu.cn.

Weina Ge, Email: gwn-06@163.com.

Min Yuan, Email: yuanmin308@163.com.

Tianyu Lei, Email: leitianyu.china@gmail.com.

Li Wang, Email: wlsh219@126.com.

Lan Zhang, Email: zhanglan1374@sohu.com.

Yuxian Li, Email: yuxianli120@gmail.com.

Tao Liu, Email: liutaocreate@gmail.com.

Wei Chen, Email: chenweiimu@gmail.com.

Wenjing Meng, Email: a15832989110@126.com.

Changkai Sun, Email: 1966659434@qq.com.

Xiaobo Cui, Email: cuixiaobo0223@foxmail.com.

Yun Bai, Email: 1063628881@qq.com.

Xiyin Wang, Email: wangxiyin@vip.sina.com.

References

- 1.Jianhui J, Yingjun Z, Hehe W, Liming Y. Genome-wide analysis and functional prediction of the Trihelix transcription factor family in rice. Hereditas. 2015;37(12):1228–1241. doi: 10.16288/j.yczz.15-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, Reuber L, Jiang CZ, Keddie J, Adam L, Pineda O, Ratcliffe OJ, Samaha RR, et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290(5499):2105–2110. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo JL, Zhao N, Lu CM. Plant Trihelix transcription factors family. Hereditas. 2012;34(12):1551–1560. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1005.2012.01551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green PJ, Kay SA, Chua NH. Sequence-specific interactions of a pea nuclear factor with light-responsive elements upstream of the rbcS-3A gene. EMBO J. 1987;6(9):2543–2549. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kay SA, Keith B, Shinozaki K, Chye ML, Chua NH. The rice phytochrome gene: structure, autoregulated expression, and binding of GT-1 to a conserved site in the 5′ upstream region. Plant Cell. 1989;1(3):351–360. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perisic O, Lam E. A tobacco DNA binding protein that interacts with a light-responsive box II element. Plant Cell. 1992;4(7):831–838. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.7.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le GJ, Li YF, Zhou DX. Transcriptional activation by Arabidopsis GT-1 may be through interaction with TFIIA-TBP-TATA complex. Plant J. 1999;18(6):663–668. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan-Levy RN, Brewer PB, Quon T, Smyth DR. The trihelix family of transcription factors--light, stress and development. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17(3):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dehesh K, Bruce WB, Quail PH. A trans-acting factor that binds to a GT-motif in a phytochrome gene promoter. Science. 1990;250(4986):1397–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.2255908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehesh K, Hung H, Tepperman JM, Quail PH. GT-2: a transcription factor with twin autonomous DNA-binding domains of closely related but different target sequence specificity. EMBO J. 1992;11(11):4131–4144. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith ME, Conceicao AD, Smyth DR. PETAL LOSS gene regulates initiation and orientation of second whorl organs in the Arabidopsis flower. Development. 1999;126(24):5635–5644. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brewer PB, Howles PA, Dorian K, Griffith ME, Ishida T, Kaplan-Levy RN, Kilinc A, Smyth DR. PETAL LOSS, a trihelix transcription factor gene, regulates perianth architecture in the Arabidopsis flower. Development. 2004;131(16):4035–4045. doi: 10.1242/dev.01279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lampugnani ER, Kilinc A, Smyth DR. PETAL LOSS is a boundary gene that inhibits growth between developing sepals in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2012;71(5):724–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin ZW, Griffith ME, Li XR, Zhu ZF, Tan LB, Fu YC, Zhang WX, Wang XK, Xie DX, Sun CQ. Origin of seed shattering in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Planta. 2007;226(1):11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang YJ, Xie KB, Hou X, Hu HH, Xiong LH. Systematic analysis of GT factor family of rice reveals a novel subfamily involved in stress responses. Mol Gen Genomics. 2010;283(2):157–169. doi: 10.1007/s00438-009-0507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitakura S, Fujita T, Ueno Y, Terakura S, Wabiko H, Machida Y. The protein encoded by oncogene 6b from agrobacterium tumefaciens interacts with a nuclear protein of tobacco. Plant Cell. 2002;14(2):451–463. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuromori T, Wada T, Kamiya A, Yuguchi M, Yokouchi T, Imura Y, Takabe H, Sakurai T, Akiyama K, Hirayama T, et al. A trial of phenome analysis using 4000 ds-insertional mutants in gene-coding regions of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006;47(4):640–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr MS, Willmann MR, Jenik PD. Is there a role for trihelix transcription factors in embryo maturation? Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7(2):205–209. doi: 10.4161/psb.18893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu C, Cai X, Ye Z, Li H. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling analysis of trihelix gene family in tomato. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;468(4):653–659. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang ZC, Liu QQ, Wang HZ, Zhang HZ, Xu XM, Li CH, Yang CP. Comprehensive analysis of trihelix genes and their expression under biotic and abiotic stresses in Populus trichocarpa. Sci Rep-Uk. 2016;6:36274. doi: 10.1038/srep36274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo JL, Tang SH, Mei FL, Peng XJ, Li J, Li XF, Yan XH, Zeng XH, Liu F, Wu YH, et al. BnSIP1-1, a Trihelix family gene, mediates abiotic stress tolerance and ABA signaling in Brassica napus. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:44. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennetzen JL, Schmutz J, Wang H, Percifield R, Hawkins J, Pontaroli AC, Estep M, Feng L, Vaughn JN, Grimwood J, et al. Reference genome sequence of the model plant Setaria. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(6):555–561. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang GY, Liu X, Quan ZW, Cheng SF, Xu X, Pan SK, Xie M, Zeng P, Yue Z, Wang WL, et al. Genome sequence of foxtail millet (Setaria italica) provides insights into grass evolution and biofuel potential. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(6):549. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandey G, Misra G, Kumari K, Gupta S, Parida SK, Chattopadhyay D, Prasad M. Genome-wide development and use of microsatellite markers for large-scale genotyping applications in foxtail millet [Setaria italica (L.)] DNA Res. 2013;20(2):197–207. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yi F, Xie SJ, Liu YW, Qi X, Yu JJ. Genome-wide characterization of microRNA in foxtail millet (Setaria italica) BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:212. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mishra AK, Muthamilarasan M, Khan Y, Parida SK, Prasad M. Genome-Wide Investigation and Expression Analyses of WD40 Protein Family in the Model Plant Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai KJ, Lu MYJ, Yang KJ, Li MY, Teng YC, Chen S, Ku MSB, Li WH. Assembling the Setaria italica L. Beauv. genome into nine chromosomes and insights into regions affecting growth and drought tolerance. Sci Rep-Uk. 2016;6:35076. doi: 10.1038/srep35076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You Q, Zhang L, Yi X, Zhang Z, Xu W, Su Z. SIFGD: Setaria italica functional genomics database. Mol Plant. 2015;8(6):967–970. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li WW, Chen M, Zhong L, Liu JM, Xu ZS, Li LC, Zhou YB, Guo CH, Ma YZ. Overexpression of the autophagy-related gene SiATG8a from foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) confers tolerance to both nitrogen starvation and drought stress in Arabidopsis. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2015;468(4):800–806. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ning N, Yuan XY, Dong SQ, Wen YY, Gao ZP, Guo MJ, Guo PY. Grain Yield and Quality of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) in Response to Tribenuron-Methyl. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aidoo MK, Bdolach E, Fait A, Lazarovitch N, Rachmilevitch S. Tolerance to high soil temperature in foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) is related to shoot and root growth and metabolism. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2016;106:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodge JG, Kellogg EA. Abscission zone development in Setaria viridis and its domesticated relative, Setaria italica. Am J Bot. 2016;103(6):998–1005. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1500499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Dong Y, Li C, Pan Y, Yu J. SiASR4, the target gene of SiARDP from Setaria italica, Improves Abiotic Stress Adaption in Plants. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:2053. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.02053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Tang S, Zhang S, Shan J, Tang C, Chen Q, Jia G, Han Y, Zhi H, Diao X. Gene mapping and functional analysis of the novel leaf color gene SiYGL1 in foxtail millet [Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv] Physiol Plant. 2016;157(1):24–37. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lightfoot E, Przelomska N, Craven M, Connell TC O, He L, Hunt HV, Jones MK. Intraspecific carbon and nitrogen isotopic variability in foxtail millet (Setaria italica) Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2016;30(13):1475–1487. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu XT, Tang S, Jia GQ, Schnable JC, Su HX, Tang CJ, Zhi H, Diao XM. The C-terminal motif of SiAGO1b is required for the regulation of growth, development and stress responses in foxtail millet (Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv) J Exp Bot. 2016;67(11):3237–3249. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ning N, Yuan XY, Dong SQ, Wen YY, Gao ZP, Guo MJ, Guo PY. Increasing selenium and yellow pigment concentrations in foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) grain with foliar application of selenite. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016;170(1):245–252. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan YL, Li JR, Jiao LC, Li C, Zhu DY, Yu JJ. A non-specific Setaria italica lipid transfer protein gene plays a critical role under abiotic stress. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1752. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y, Weng QY, Song JH, Ma HL, Yuan JC, Dong ZP, Liu YH. Bioinformatics analysis of NBS-LRR encoding resistance genes in Setaria italica. Biochem Genet. 2016;54(3):232–248. doi: 10.1007/s10528-016-9715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alagarasan G, Dubey M, Aswathy KS, Chandel G. Genome wide identification of orthologous ZIP genes associated with zinc and Iron translocation in Setaria italica. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:775. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu KG, Qi SH, Li D, Jin CY, Gao CH, Duan SW, Feng BL, Chen MX. TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA 1 ubiquitously regulates plant growth and development from Arabidopsis to foxtail millet (Setaria italica) Plant Sci. 2017;254:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pandey G, Yadav CB, Sahu PP, Muthamilarasan M, Prasad M. Salinity induced differential methylation patterns in contrasting cultivars of foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36(5):759–772. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Liu BL, Zheng GW, Zhang AY, Li RZ. Genome-wide characterization of the SiDof gene family in foxtail millet (Setaria italica) Biosystems. 2017;151:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muthamilarasan M, Khandelwal R, Yadav CB, Bonthala VS, Khan Y, Prasad M. Identification and molecular characterization of MYB Transcription Factor Superfamily in C4 model plant foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) Plos One. 2014;9(10):e109920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lata C, Mishra AK, Muthamilarasan M, Bonthala VS, Khan Y, Prasad M. Genome-wide investigation and expression profiling of AP2/ERF transcription factor superfamily in foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) Plos One. 2014;9(11):e113092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puranik S, Sahu PP, Mandal SN, VS B, Parida SK, Prasad M. Comprehensive genome-wide survey, genomic constitution and expression profiling of the NAC transcription factor family in foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) PloS one. 2013;8(5):e64594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mount DW. Using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2007;2007(14):pdb.top17. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART 7: recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(D1):D302–D305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Artimo P, Jonnalagedda M, Arnold K, Baratin D, Csardi G, de Castro E, Duvaud S, Flegel V, Fortier A, Gasteiger E, et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(W1):W597–W603. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin JP, Tian F, Yang DC, Meng YQ, Kong L, Luo JC, Gao G. PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D1040–D1045. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu B, Jin J, Guo AY, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(8):1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C, Li WW. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W369–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren JY, Li WW, Noble WS. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14(6):1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X, Wang J, Jin D, Guo H, Lee TH, Liu T, Paterson AH. Genome alignment spanning major Poaceae lineages reveals heterogeneous evolutionary rates and alters inferred dates for key evolutionary events. Mol Plant. 2015;8(6):885–898. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, et al. Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang ZH. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13(9):2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos A, Tsafou KP, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(D1):D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang W, Wu P, Liu T, Ren H, Li Y, Hou X. Genome-wide Analysis and Expression Divergence of the Trihelix family in Brassica Rapa: Insight into the Evolutionary Patterns in Plants. Sci Rep-Uk. 2017;7(1):6463. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06935-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Basic information of foxtail millet Trihelix transcription factor genes. (DOCX 15 kb)

Figure S1. Millet Trihelix family genetic structure analysis. (JPG 1489 kb)

Table S2. Conservative motif in Trihelix transcription factor genes. (DOCX 13 kb)

Figure S2. Trihelix family conservative domain feature analysis in foxtail millet. Stack height in different sites of amino acid shows conservative domains, the stack height of a single amino acid shows the relative frequency of the amino acid in this location. Red triangle shows that conservative core amino acids Trp (W) - 1, Trp (W) – 64 and Cys (C) -100. (JPG 740 kb)

Table S3. RPKM values of millet Trihelix transcription factor genes in the different organs. (DOCX 17 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study were included in this published article and the Additional files. We have been using public data and do not have produced sequence data by ourselves.