Abstract

An efficient and direct oxidation of aromatic amines to aromatic azo-compounds has been achieved using a MnO2@g- C3N4 catalyst under visible light as a source of energy at room temperature.

Keywords: Graphitic carbon nitride, photo-catalyst, manganese dioxide, heterogeneous catalysis, aromatic azo-compounds

Introduction

Since the discovery of azobenzene derivatives, these compounds have been traditionally employed as organic dyes [1]. Additionally, aromatic azo compounds are important raw materials with industrial applications as food additives, therapeutic agents, radical reaction initiators, drugs, photochemical molecular switches, and liquid crystals [2–4]. Conventional methods for the synthesis of aromatic azo compounds entail coupling of stoichiometric amount of electron rich compounds with diazonium salts [5–6]. However, these protocols generate copious amount of inorganic waste. There are several reports on the synthesis of azo-compounds such as Mills reaction, reduction of azoxybenzene, Wallach reactions, oxidation of amines, triazine rearrangement, thermolysis of azides, metal catalyzed coupling of arylhydrazines [7–10]. These methods are limited in terms of the substrate scope because of their intrinsic reaction mechanism showing the combination of electron rich and electron deficient aromatic amines. Garcia et al. reported the synthesis of aromatic azo- compounds from nitroaromatics using gold nanoparticles supported on titanium dioxide (TiO2) at primarily 9 bar hydrogen and 5 bar oxygen pressure [11]. Recently, Zhang and coworkers synthesized azo compounds via aerobic oxidative dehydrogenate coupling of anilines using copper bromide and molecular oxygen as an oxidant [12]. Gu et al. reported a worm-like palladium nano-catalyst for the synthesis of aromatic azo compounds from nitro- benzenes under hydrogen pressure [13]. These inspiring methods, however, require expensive catalysts, high temperature and high oxygen pressure. Engaged in the development of benign protocols in organic synthesis [14–18] involving the use of inexpensive, reusable and efficient heterogeneous catalysts for the sustainable chemical advancements, herein, we report a simple and efficient method for the direct synthesis of aromatic azo-compounds from anilines derivatives using MnO2@g-C3N4 under photochemical conditions.

Experimental

Material/ chemicals details

KMnO4, Urea, HCl and all aromatic amines were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (United States of America)

Synthesis of graphitic carbon nitride [19]

The 1.0 g urea was taken in a ceramic crucible and calcinated at 500 °C for 3 hours in a furnace at ambient atmosphere. The temperature was brought down to room temperature and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) was isolated as pale yellow solid.

Synthesis of graphitic carbon nitride supported manganese dioxide (MnO2@g-C3N4) [20]

100 mg of g-C3N4 was dissolved in 40 ml water followed by the addition of 31 mg of KMnO4 and 0.5 ml (1.0 M) HCl. The ensuing mixture was stirred for 10 min at room temperature. The solution was transferred into a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and heated at 100 °C for 4 hours. The product was centrifuged, washed with methanol and dried under vacuum at 50 °C to afford the catalyst, graphitic carbon nitride supported manganese dioxide (MnO2@g-C3N4), as an off-white solid (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Synthesis of MnO2@g-C3N4

Synthesis of aromatic azo-compounds

In a 25 mL round bottomed flask, aromatic amine (1 mmol), catalyst MnO2@g-C3N4 (10 mg), 5 mL of acetonitrile were added and exposed to visible light irradiation using 20 watt domestic bulb. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. After completion of the reaction, the MnO2@g-C3N4 catalyst was separated using a centrifuge. The product was extracted using ethyl acetate, dried over sodium sulfate, concentrated and characterized using NMR.

Recycling of MnO2@g-C3N4 catalyst

To establish the recyclability of the MnO2@g-C3N4 catalyst for the oxidation of aromatic amines to aromatic azo-compounds, a set of experiments were performed using aniline as a model substrate. After the completion of each reaction the catalyst was recovered using centrifuge, washed with methanol and reused for the next reaction of aniline as fresh reagent. The MnO2@g-C3N4 catalyst could be recycled and reused up to five times without losing its activity (Fig. 2). The SEM and XRD pattern of the catalyst before and after the reaction confirmed that there was no significant change in the morphology of the catalyst which also reaffirms the high stability of MnO2@g-C3N4 catalyst in the course of reaction (ESI, S1 and S2).

Fig. 2.

Recycling of MnO2@g-C3N4catalyst

Results and discussion

The synthesized catalyst, MnO2@g-C3N4 was characterized using scanning electron microscope (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD). The SEM images (Fig. 3) of MnO2@g-C3N4 confirmed the immobilization of manganese dioxide on g-C3N4 with the visible difference in their morphology before and after the impregnation; which was further supported by XRD analysis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

SEM image of g-C3N4 (a, b) and MnO2@g-C3N4 (c, d)

Fig. 4.

XRD analysis of a) g-C3N4; b) MnO2@g-C3N4

Implementing the inherent affinity of graphitic carbon nitride towards the visible light, the activity of graphitic carbon nitride supported manganese dioxide was examined in the oxidation of aniline at room temperature. The preliminary outcomes acquired during the reaction optimization are summarized in Table 1. The oxidation of aniline into azobenzene was performed using 2 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg and 15 mg of MnO2@g-C3N4 in acetonitrile (Table 1; entries 1–4). 10 mg of MnO2@g-C3N4 catalyst was found to be most effective as it offered highest yield of azobenzene (Table 1, entry 3). Further increase in wt% of MnO2@g-C3N4 did not show any significant change in yield (Table 1, entry 4). The control experiments were performed using g-C3N4 (Table 1, entry 5) and MnO2 (Table 1, entry 6); MnO2 gave only 44% of azobenzene. In the absence of visible light the starting material remained intact as it gave no desired product (Table 1, entry 7).

Table 1.

Reaction optimizationa

| Entry | Catalyst | Yieldb |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | MnO2@g-C3N4 (2 mg) | 33% |

| 2 | MnO2@g-C3N4 (5 mg) | 78% |

| 3 | MnO2@g-C3N4 (10 mg) | 93% |

| 4 | MnO2@g-C3N4 (15 mg) | 93% |

| 5 | g-C3N4 (20 mg) | 6% |

| 6 | MnO2 (20 mg) | 44% |

| 7c | MnO2@g-C3N4 (10 mg) | - |

Reaction condition:

) Aniline (1 mmol), CH3CN (5 ml), 20 W domestic bulb, Room Temperature, 12 h;

) Isolated yield;

) Reaction was performed in dark

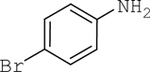

Accordingly, a wide range of substituted aromatic amines were subjected towards the direct oxidation at room temperature using 20 W domestic bulb as a source of visible light (Table 2, entries 1–5). The reaction with different substituted amines bearing electron donating (Table 2; entries 2–3) and electron withdrawing substituents (Table 2; entries 4–5) did not show any significant difference in reactivity and product outcome (Table 2; entries 2–5).

Table 2.

Synthesis of aromatic azo compoundsa

| Entry | Reactant | Product | Yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

93% |

| 2 |  |

|

91% |

| 3 |  |

|

91% |

| 4 |  |

|

93% |

| 5 |  |

|

92% |

Reaction condition:

) Aromatic amine (1 mmol), CH3CN (5 ml), 20 W domestic bulb, Room temperature, 12 h;

) Isolated Yield

Conclusion

The present work represents a simple and highly efficient method for the synthesis of aromatic azo- compounds using photoactive MnO2@g-C3N4 catalyst at room temperature. The prominent aspect of this reaction is the use of visible light, which was trapped by MnO2@g-C3N4 and used in the direct oxidation of aromatic amines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

SV was supported by the Postgraduate Research Program at the National Risk Management Research Laboratory administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, through its Office of Research and Development, funded and managed the research described herein. It has been subjected to the Agency’s administrative review and has been approved for external publication. Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Agency, therefore, no official endorsement should be inferred. Any mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

References

- 1.Bafana A; Devi SS; Chakrabarti T Environ. Rev 2011, 19, 350 DOI: 10.1139/a11-018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh AK; Das J; Majumdar NJ Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 6185 DOI: 10.1021/ja954286x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burland DM; Miller RD; Walsh CA Chem. Rev 1994, 94, 31 DOI: 10.1021/cr00025a002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghosh S; Banthia AK; Chen Z Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 2889. 10.1016/j.tet.2005.01.052 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gung BW; Taylor RT J. Chem. Educ 2004, 81, 1630 DOI: 10.1021/ed081p1630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haghbeen K; Tan EW J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 4503 DOI: 10.1021/jo972151z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vozza JF J. Org. Chem 1969, 34, 3219 DOI: 10.1021/jo01262a104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merino E Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 3835 DOI: 10.1039/C0CS00183J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey HH; Lee RD; Marks TJ J. Org. Chem 1999, 64, 4976 DOI: 10.1021/jo990235x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacon ES; Richardson DH J. Chem. Soc 1932, 884 DOI: 10.1039/JR9320000884 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grirrane A; Corma A; García H Science 2008, 322, 1661 DOI: 10.1126/science.1166401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang C; Jiao N; Angew. Chem 2010, 122, 6310; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010, 49, 6174 DOI: 10.1002/anie.201001651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu L; Cao X; Shi L; Qi F; Guo Z; Lu J; Gu H Org. Lett 2011, 13, 5640 DOI: 10.1021/ol202362f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varma RS Green Chem 2014, 16, 2027 DOI: 10.1039/C3GC42640H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varma RS ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng 2016. DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b01623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma S; Baig RBN; Han C; Nadagouda MN; Varma RS Green Chem 2015, 18, 251 DOI: 10.1039/C5GC02025E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verma S; Nasir Baig RB; Nadagouda MN; Varma RS ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng 2016, 4, 2333 DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verma S; Baig RBN; Nadagouda MN; Varma RS ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng 2016, 4, 1094 DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verma S; Baig RBN; Nadagouda MN; Varma RS Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 15554 DOI: 10.1039/C5CC05895C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumari S; Shekhara A; Pathak DD RSC Adv, 2014, 4, 61187 DOI: 10.1039/C4RA11549J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.